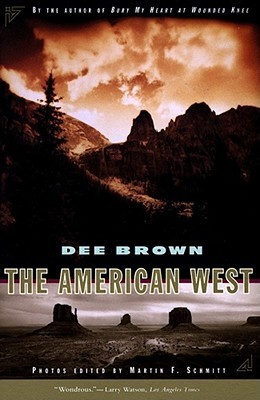

| Title | : | The American West |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0684804417 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780684804415 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 448 |

| Publication | : | First published December 1, 1994 |

Beginning with the demise of the Native Americans of the Plains, Brown depicts the onrush of the burgeoning cattle trade and the waves of immigrants who ultimately “settled” the land. In the retelling of this oft-told saga, Brown has demonstrated once again his abilities as a master storyteller and an entertaining popular historian.

By turns heroic, tragic, and even humorous, The American West brings to life American tragedy and triumph in the years from 1840 to the turn of the century, and a roster of characters both great and small: Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, Geronimo, Dull Knife, Crazy Horse, Captain Jack, John H. Tunstall, Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, Wyatt Earp, the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, Wild Bill Hickok, Charles Goodnight, Oliver Loving, Buffalo Bill, and many others.

The American West is about cattle and the railroads; it is about settlers who came to claim a land not originally their own and how they slowly imposed law and order on these wild and untamed places; and it is about the wanton destruction of the Native American way of life. This is epic history at its best and popular history at its most readable.

This new work is culled from Dee Brown’s highly acclaimed writings, which instantly established him as one of America’s foremost Western authorities. Fully revised, rewritten, and edited into one seamless account of America’s most famous frontier, this epic narrative, along with the introduction and a chronological table of events, etches an unforgettable and poignant portrait. The American West is at once a tribute to the West and a majestic new peak for a writer whose long and successful career has been synonymous with excellence in frontier history.

The American West Reviews

-

World War II found librarian Dee Brown stationed in Washington, DC. He was assigned to Army Ground Forces headquarters at the old Army War College. Here he met fellow librarian Martin Schmitt and, through the course of their service together, they bonded over a shared interest in Western history. Their duties sometimes brought them to the Signal Corps photograph files stored at the Pentagon - a treasure trove of ancient images, the most compelling of which were cached in the Indian Wars collection. In the waning days of their military employment they set about making prints of these pictures, which were eventually turned into three books: Fighting Indians of the West, Trail Driving Days, and The Settlers' West. Brown captioned the pictures and composed a loose narrative thread to set the images in context.

This is important. It's important to know that photographs were the impetus for this author. His inspiration did not come through ideas, disputes, determinations or events, as it does for most historians. He had no ardent desire to grapple with the Beast of Posterity. Here was a mind less concerned with the how and why of the past than it was with what, exactly, it was he was looking at. A rare angle of approach - and, truth be told, that's where a lot of the fun is tapped for the reader of history. I grow as bored as the rest with chronologies, charts, graphs, maps, the dull whine of a dusty academic and the chalkboard screech of any intellect presumptuous enough to imagine I need my thinking done for me. It's tough to tolerate...and refreshing, every so often, to discover you don't have to.

It is true that, in terms of scholarship, The American West skims over several important incidents and consequential stages of the settlement process, but what it does bring to the table is material rich in anecdote, personality and descriptive force. Brown builds on the bones of character - be it the character of a person, a tribe, a garrison, a ranch, a railroad or a landscape; he's sketching the volatile temperament of the frontier thrust. It's fundamental stuff, filled with life and legend, triumph and atrocity, grace and greed. In short, while he may have moved on from his photographs, Brown certainly hasn't abandoned his images and shares that fascination with scenes like this:

The Medicine Lodge Creek Council which was held in Kansas in October 1867 was a marvelous spectacle in which both the uniformed troops of the army and the bedecked warriors of the southern plains performed splendidly. General W.S. Harney marched his soldiers and wagon trains to the meeting place with considerable pomp and ceremony, but the Indians surpassed him by riding up in a swirling formation of five concentric circles, their horses striped with war paint, the riders wearing warbonnets and carrying gay battle streamers. The great whirling wheel of color and motion stopped suddenly at the edge of the soldiers' positions. Then an opening was formed, and the great chiefs waited dramatically and silently for the outnumbered white men to step inside and prove their bravery and good faith.

Not every history can read like that. Most history probably shouldn't. But, and you really can't escape this, more people would buy it if it did. -

This was my second read (the last was years ago now) - and overall I enjoyed it once more.

Numerous different topics are touched on in the course of the book.

Some of them could have been dealt with in greater detail to my way of thinking. I was left wanting to know more on several occasions.

The Introduction looks at what was involved in gathering the source information required to put the novel together.

A lot of work!

To my way of thinking the last chapter (Law, Order and Politics) doesn't allow the book to end on anything like a high. That alone probably contributed the most to giving me a feeling of being happy to get to the finish.

It's probably the most boring twenty pages of the whole book.

Shame it was where it was.

For someone starting out to explore the stories of the Old West, its characters and its history, 'The American West' would make a good starting place.

For that reason I'd recommend it.

-

I really enjoyed this book even if not new. If you want a good overview of the settling of the West, the cowboys, Native Americans, soldiers, dance hall girls, gamblers, settlers, thieves, con artists and more, this is good start.

-

The American West looms large in our collective imagination – a frontier land of limitless potentiality and possibility – and even if the West of the American mind is sometimes more myth than reality, the region itself remains a place of vast importance, and Dee Brown brings it to life well in his book The American West.

Dee Brown grew up in Arkansas, a Southern state with Western cultural elements – a factor that may have nourished his lifelong interest in the West. In his youth he befriended a Native American who played for the local minor-league baseball team – learning, in the process, that the realities of Native American life, culture, and history were nothing like what he had seen in the movies. That interest in Native American life remained with Lee throughout his career as a librarian for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and later the University of Illinois; and it encouraged the writing of his best-known book, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West (1970).

In those long-ago times, a book like Wounded Knee, one that looked at the history of the American West from the perspective of Native Americans, was something profoundly new and even radical; nowadays, it is much more the norm. Dee Brown did much to bring about that change in the historiography of the American West. Small wonder that so many readers of Wounded Knee concluded, wrongly, that Brown must be Native American himself.

The American West is a more general history of the region, but Brown pays due attention to the Native Americans who were the first and original inhabitants of the region. It should be no surprise that Brown emphasizes the difficulties and travails that faced Native American nations like the Sioux, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche, Modoc, Nez Percé, and Chiricahua – and Native American leaders like Red Cloud, Black Kettle, Cochise, Sitting Bull, Dull Knife, Captain Jack, Chief Joseph, and Geronimo – as the tide of Anglo-American settlement swept across the West.

Brown’s sympathy for the situation of Native Americans, and his anger at white cruelty and injustice toward American Indians, comes through in his description of a U.S. cavalry raid on a peaceful Cheyenne camp in November of 1864. The chief, Black Kettle, had even raised a U.S. flag above his tent, to indicate his peaceful intentions toward the United States of America – but that flag did not help him that day:

For no apparent reason other than hatred, Colonel J.M. Chivington and his Colorado Volunteers attacked this camp in a surprise dawn raid….It has been charged that the goldfield volunteers, fearful of being called east to fight in the Civil War, deliberately attempted to foment an Indian war which would keep them at home. Whatever the reason, the indiscriminate slaughter of the surprised Cheyennes – men, women, and children – was so appalling that some of the most hard-bitten frontiersmen were disgusted. Kit Carson, who could scarcely be called a lover of the Indians, described the Sand Creek affair as a cold-blooded massacre. “No one but a coward or a dog would have had a part in it,” he said. In the thick of the battle, Black Kettle had seen his wife shot down as she tried to flee up a streambed. (p. 100)

Along with its focus on the Native Americans, the original people of the West, The American West also pays attention to other important people of the region – and the reader with an enthusiasm for Western history and culture will encounter many familiar names and personages here, as with Brown’s depiction of “Wild Bill” Hickok at the time when Hickok was sheriff of Abilene, Kansas:

A tall, graceful man and a spectacular gunfighter, Wild Bill patrolled Texas Street by walking in the center. His long auburn hair hanging in ringlets over his shoulders and his small, finely formed hands and feet gave him a feminine appearance. But everyone respected Wild Bill as a quick-draw artist. He usually wore a pair of ivory-hilted and silver-mounted pistols thrust into a richly embroidered sash. His shirts were of the finest linen and his boots of the thinnest kid leather. (pp. 199-201)

Having visited the town of Deadwood, South Dakota, where Hickok was shot in the back and killed during a poker game in August of 1876 – supposedly while holding aces and eights, the “dead man’s hand” – I was somewhat surprised that Brown did not include that aspect of the story. But the “dead man’s hand” story did not appear until the 1920’s, and Brown seems determined to stay true to the known facts of the American West’s history. And that task is not easy – Brown would have no doubt known well the idea expressed by the newspaper editor in John Ford’s film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962): “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Quite sensibly, Brown lets the eminent figures of American West history speak for themselves whenever possible, as when he provides Pat Garrett’s account of entering Billy the Kid’s home and killing the notorious outlaw in July of 1881:

“He raised his pistol quickly,” Garrett says in his account of the final scene. “Retreating rapidly across the room he repeated: ‘Quien es? Quien es?’ [‘Who is it? Who is it?'] All this occurred in a moment. Quickly as possible I drew my revolver and fired, threw my body aside, and fired again. The second shot was useless. The Kid fell dead. He never spoke. A struggle or two, a little strangling sound as he gasped for breath, and the Kid was with his many victims.” (pp. 308-09)

But the reader of The American West will also learn about figures from the region’s history that may not be as readily familiar as “Wild Bill” Hickok, Pat Garrett, and Billy the Kid. One learns, for example, about bold women outlaws who demonstrated their own tenacity and toughness just as their male counterparts were disappearing from the Western scene. When one such outlaw, Rose of the Cimarron, wanted to help her lover George “Bitter Creek” Newcombe, who had been caught in a shootout without his rifle or ammunition belt, she showed courage and presence of mind:

Always resourceful, Rose improvised a rope from stripped bedsheets and slid to the ground through a side window. Trusting the chivalrous Western marshals would not shoot an apparently unarmed woman, she concealed the rifle and belt beneath her flowing skirts and rushed across to the building where Bitter Creek was waiting. Thanks to Rose, he survived this bloody battle… (p. 405)

Always faithful to the facts, Brown dutifully notes that “Like many frontier characters, Rose of the Cimarron may be more folklore than fact” (p. 405); but when reading her story, I found myself thinking that this is one of those stories that, even if it didn’t happen, should have.

The public appetite for stories of the American West seems inexhaustible; and if you are one of the many readers who is always looking for another account of the challenging, exhilarating, dangerous life on the Western frontier, then Dee Brown’s The American West should work well for you. -

Dull

-

"American West" is the synthesis of Brown's and Schmitt's three earliest books--"Fighting Indians of the West," "Trail Driving Days," and "The Settlers' West"--and in the introduction he tells how they researched and wrote those books during and just after World War II, while the both of them were stationed in Washington D.C., as Army librarians. Also in the introduction, Brown tells how the American West has morphed from a reality into a myth, and even a metaphor. But he points out, "Today it has become fashionable to mock the myths and folklore of the American West, Yet, if we trace the origin of almost any myth and tale we will usually find an actual even, a real setting, an original conception, a living human being. We must accept the fact that the Old West was simply a place of magic and wonders...But let us be wise enough to learn the true history so that we can recognize a myth when we see one."

And "true history" is what concerns Brown most in this book. Even though he sees the American West in terms of an epic saga, from its optimistic and well-intentioned beginnings to its ignoble and tragicomic decline, he reveals it through its smallest component, the individual Indians, settlers, cowboys and civilizers of the West, giving them voice through their own journals, diaries and letters, illustrating their stories with amazing photographs of the period and maps to help establish a sense of place.

The twenty-nine chapters of the book work together to weave a vast tapestry showing the grand sweep of the region's history, but in each chapter it is the individual threads that are examined, the lives of hope-filled idealists, faith-brimming preachers, foolish dreamers, hard-eyed grifters, tight-fisted bankers and shopkeepers, and visionaries who needed but land and freedom to clothe their visions with flesh; they were protected, at least some of the time, by soldiers carrying old grudges into new lands, and menaced by Indians who never quite realized, except maybe at the end, what these newcomers represented or that they were better at being Indians than the Indians themselves.

Most people probably know Brown from his book "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee," but people coming to "American West" expecting a similar experience will be disappointed. This book is much more even-handed, much less prejudiced. While that book was written from the viewpoint of a victim, the present book is written from a more balanced viewpoint, an historian who sees foolishness and hope and atrocities in the actions of all the players in the Old West. The book is meticulously researched and the narrative is crisp and clear, but it is only when Brown lets the characters tell their own stories that the book seems to live. This is a good book for the history buff, but it is perhaps an even better book for the fan of Western fiction, for it will provide the reader a depth of understanding that will allow a greater appreciation (or bring a critical eye) to the romanticized tales that have sprung from harsh reality. -

I like to read about the early west.

-

I love reading about American west!

-

Almost like watching a whole Saturday's worth of John Wayne movies.

-

A re-read - great single volume of something almost impossible to write a single volume history of. Particularly enjoyed revisiting the passage on the great grasshopper plague of 1874.

-

Brown begins his narrative with Westward March, a ramble from the steamboat traffic on the Missouri to settlement. Along the way he touches on travellers on the various trails west and sometime during the discovery - a transformation of the west from Great American Desert to a Plains that could be settled, farmed, and ranched - the pioneer “appeared as a special type, imbued with the spirit of Manifest Destiny...as the pioneers aged and prospered, they reminisced in a romantic spirit,” (Brown, 1995; 39).

Brown’s prose is quick to make a point. His work is easy to consume. Rather than run through the history of the American West in a timeline, topics are grouped into chapters (ex. railroad, cattle and drives & trails, cowboys, chiefs and tribes). The American West has twenty-nine chapters averaging about a dozen pages. Various images, mostly maps, illustrate the narrative of movements, campaigns, and land loss.

The American West is essentially a collection of essays about the American West. Each chapter or essay feels sensational, like a race to get from 1800 to 1900. Brown’s chapters about native peoples are rousing and heartbreaking. These chapters reach back for the energy of Brown’s “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.” Reading Wounded Knee and reading the struggle of native survival should provoke sympathy in readers, perhaps even a sense of outrage.

“Black Kettle...stepped quickly outside...to alarm the village...even when bent on a massacre, Custer was a showman...slashing at fleeing Indians with their sabers...more than a hundred Cheyenne warriors were killed, as well as many more women and children never counted,” (Brown, 1995; 106 & 107). As heartbreaking as these histories are, they provoke non-natives to visit these places on a kind of pilgrimage of absolution.

Brown breaks down the treaty process in Chapter 8: Treaties and the Thieves’ Road. The Thieves’ Road is the Ocheti Sakowin term for General Custer’s 1874 Black Hills Expedition. The Indian Peace Commission announced a great gathering and disbursement at Fort Laramie in 1851. Several tribes show up to articulate their territorial occupation. Two-thirds of adult men sign the treaty agreeing to definitions of their place in the landscape. The Indian Peace Commission took this treaty to Congress where the terms were amended. The treaty was sent to the president to sign into law. Not only were treaty terms re-written, but as Brown explains it, the federal government could not enforce its own terms. Squatters and miners entered the Black Hills against the terms of treaties, who are forced out or violently killed, followed by escalating violence, which lead to the US military coming in to force a land cession or treaty.

In Chapter 12: The Myth and Its Makers, Brown explains the Americans' aggrandizement of the American West, how conflicts like the Little Bighorn were the contemporary equivalent of ancient battles of the Old World. In the case of LBH, that conflict was compared to the ancient Battle of Thermopolis (aka, or “300”). Americans were so caught up in their own mythmaking, some even took the story on the road with their Wild West shows. But Wild West shows were only part of the mythmaking. Literature, photography, and the early films helped to fix the Old West in the minds and hearts of the world citizens. General Custer’s widow, Elizabeth “Libby” Bacon-Custer survived her husband for decades, dedicated the remainder of her life as a living testimony to the public preservation of the memory of her late husband.

Brown dedicates three chapters to the story of the Lakota and Sitting Bull, the US military response to escalating conflicts on the 1850s and 1860s, and the challenges of the Cheyenne on the Great Plains. There is more preparation in the indigenous story building up to the conflicts in the Powder River Country than many books coming out today which focus on the Little Bighorn.

Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce get a chapter, though the story of that people is best consumed in Kent Nerburn’s Chief Joseph and the Flight of the Nez Perce. In Brown’s summary fashion readers are informed of the peaceful Niimiipuu (Nez Perce) and their acceptance of Christianity, their gradual resistance to settlers bullying them out of their ancestral idyllic homeland, the Lapwai Valley. Years of depredations at the hands of settlers and escalating violence lead to a split in the Nez Perce with about half leaving their homeland for a chance at lasting traditional freedom with Sitting Bull and the Lakota in Canada. Brown carefully and briefly constructs a gripping narrative of the Nez Perce’ 500 mile long flight to Fort Walsh. They come heartbreakingly close - just eighteen miles south of the Canadian border at Bearpaw Mountain. Their flight comes to a close with Joseph giving his most renowned “from where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever” speech. The Nez Perce were removed to Oklahoma and Joseph was later allowed to settle amongst the Coeur d'Alene in Washington. Joseph, a political exile, was never allowed to see his homeland again.

The American West as an introduction to American western history is powerful and emotive. It is sensational and provocative. One either reads it in disbelief or is so profoundly struck by the stark injustice one may experience a bout of powerlessness, or both. Brown can’t escape his own construction of the tragedy of the American West. His narrative builds to the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890. “The vision of the peaceful Paiute dreamer, Wovoka, had come to an end with the Battle [sic] of Wounded Knee. And so had all the long and tragic years of Indian resistance of the western plains,” (Brown, 1995; 373).

Brown has earned a place on this reader’s shelf, and through the years has been read a handful of times. Each time as provocative and emotive as though it were the first. The author wrote a book of his time. Perhaps if Brown were alive today, he may find that indigenous resistance is still alive and well in the American West. -

I'm don't have a particular interest in American history. I knew that Dee Brown wrote Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee and I loved the film. There is nothing actually wrong with this book. I just didn't get on with the style of writing. For me if you want to hear about the history of the West then watch Ken Burns' documentary series.

-

This western primer tells the stories of Native Americans, settlers, cowboys, miners, and ranchers. The narrative explains in a straightforward manner the conflicts, struggles, and conquests that led to settlement of the West. lj

-

We head out west in a month and this has provided a good general 30k foot overview of western history. The writing is dated, but the photos are excellent and the right amount of detail is given most of the time to keep the flow moving.

-

This was a really interesting read, stripping away something of the mythology of the pioneering west as filtered through folk tales and Hollywood.

Very enjoyable read, and looking forward to more of the same. -

Really liked my first foray into American history, but just as I was getting interested in a particular subject the next chapter would go elsewhere. This I found a little frustrating. Will read more from this Author in the future

-

What a snooze. Hard to keep awake reading this book. A few interesting facts but it was the stories never heard before about famous people that kept me going what? Where did you get that fact. Made me wonder how much was made up.

-

Lots of history in one book!

-

Vividly written book that covers the major stories and themes of the history of the American West.

-

Great introduction on the American West history. In the end you think how America can preach Democracy and Freedom knowing what they did to the Indians.

-

I use this book as a text for my History of the West course that I teach in a high school setting. Brown covers much of the experiences with a wealth of photos.

-

Very interesting book and a nice compliment to the other Wild West book I just read. Can wait for this Summer

-

I like the theme of this book is an unparalleled history Where it has an unexpected outcome very good