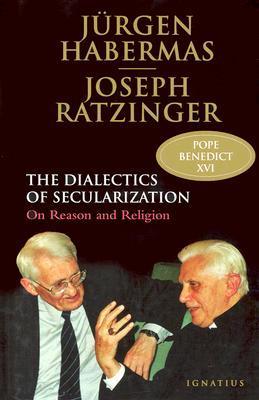

| Title | : | The Dialectics of Secularization: On Reason and Religion |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1586171666 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781586171667 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 85 |

| Publication | : | First published July 15, 2005 |

Jurgen Habermas has surprised many observers with his call for "the secular society to acquire a new understanding of religious convictions", as Florian Schuller, director of the Catholic Academy of Bavaria, describes it his foreword. Habermas discusses whether secular reason provides sufficient grounds for a democratic constitutional state. Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI argues for the necessity of certain moral principles for maintaining a free state, and for the importance of genuine reason and authentic religion, rather than what he calls "pathologies of reason and religion", in order to uphold the states moral foundations. Both men insist that proponents of secular reason and religious conviction should learn from each other, even as they differ over the particular ways that mutual learning should occur.

The Dialectics of Secularization: On Reason and Religion Reviews

-

The Catholic commentator Daniel Johnson once derided Jürgen Habermas as "

the pope of secularism." There is some truth to this. Habermas’s thesis of the Linguistification of the Sacred of the 1980s equated modernization with secularization, and his Discourse Theory of Democracy of the 1990s sought to provide a rational foundation for secular politics. It therefore came as a surprise to everyone when, in the early 2000s, he declared that secular reason still had things to learn from religion and held a public dialogue with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the soon-to-be Pope Benedict XVI and very embodiment of Catholic orthodoxy.

The Dialectics of Secularization (2005) transcribes this unlikely dialogue. The subject of their exchange is whether the secular state depends for its legitimacy on pre-political sources of authority. Predictably, Habermas answers in the negative: his theory of democracy provides a convincing account of the legitimacy of the state without appealing to such authority. At the same time, however, he insists that the democratic process cannot function unless citizens’ various ethical outlooks, including their religious traditions, foster in them the social solidarity and normative intuitions they need to participate in public life. In this much weaker sense, the state does depend on pre-political resources.

Ratzinger, just as predictably, takes the opposite position. Against Habermas, he insists that the democratic will cannot be the final arbiter of rightness and wrongness. Majorities, he reminds us, can be blind or unjust. Any coherent account of political legitimacy therefore relies on pre-political rights of the kind posited by the Natural Law tradition. The problem, of course, is that these presuppose a view of the rational intelligibility of the natural world that has largely been displaced since the Scientific Revolution and sensitivity to them cannot be restored by secular reason alone.

Habermas’ dialogue with Ratzinger finds its echo in his more recent work. In Between Naturalism and Religion (2005), for example, he worries that the process of modernization is spinning out of control and undermining both the normative resources necessary for democratic self-determination. And, again to everyone’s surprise, he points to religious traditions as a potential safeguard against these destructive tendencies. Despite their very different starting-points, therefore, Habermas and Ratzinger share a common intuition: for all the talk about secularization, religion has not yet exhausted its social and political relevance. -

1. کلیاتی درباب کتاب:

بخش عمده کتاب شامل متن سخنرانی دو متفکر برجسته معاصر درباب پرسشی مشترک است که آن پرسش، در حقیقت این است که «شالوده اخلاقی پیشاسیاسی یک دولت آزاد چیست؟» یک سوی این گفتگو یورگن هابرماس قرار داد از جمله جامعه شناسان شهیر آلمانی است و طرف دیگر، یوزف راتزینگر قرار دارد که دکتری اش را در حوزه الهیات گرفته و در سال 2005 به عنوان جانشین پاپ ژان پل دوم انتخاب شد و به بندیکت شازدهم نام گرفت.

چنانچه روشن است، این پرسش ذیل عقل عملی تعریف می شود که یکی از حوزه هایی مغفول در زمینه رابطه بین عقل و دین است. در این گفتگو، هر دو طرف بحث تلاش می کنند نظر خود را درباب نسبتی که باید سیاست به طور کلی با دین داشته باشد را بیان نمایند. فلورین شولر که به عنوان ویراستار نام وی درج شده است و پیشگفتاری بر این گفتگو نوشته است، در حقیقت مدیر فرهنگستان کاتولیک باواریا است و پیشنهاد اولیه طرح این گفتگو توسط او مطرح شده است.

2. شرح گفتگو:

پاسخ کوتاه هر یک از اطراف این گفتگو، چنانچه شولر خاطر نشان کرده است، آن است که به نظر هابرماس، این عقل عملی پسامتافیزیکی یعنی تفکر سکولار است که عامل وحدت بخش سیاست به عنوان عامل مشروعیت حکومت است، در حالی که به عقیده راتزینگر، «ما پیش از هر عقیده اجتماعی عقلانی، واقعیت انسان را به عنوان مخلوقی داریم که حیاتش را از خالق می گیرد» برای همین طبیعتاً نمی توان موضع دینی شهروندان را تعلیق کرد و باید دین را به عنوان شالوده اخلاقی پیشاسیاسی یک دولت ازاد در نظر گرفت. (ص 17)

2.1. هابرماس: شالوده های پیشاسیاسی دولت قانونی مردم سالار

هابرماس بحث خود را با طرح پرسشی قدیمی توسط ولفگانگ بوکنفورد آغاز می کند که: آیا دولت لیبرال و سکولاری وجود دارد که بر پیش فرض های هنجاری بنا شده باشد اما خود نتواند از آن ها پشتیبانی کند؟ تلاش هابرماس نشان دادن آن است که چگونه یک دولت لیبرال می تواند به شکلی خودکفا (ص 31)، متکی به فرآیندهای خود انسجام اجتماعی را بدون ارجاع به هیچ نظام متافیزیکی یا دینی حفظ کند. ولی تلاش می کند با طرح چنین وضعیتی، عملاً نقش هر دین داران و غیردین داران را در این سیاست سکولار و نظام لیبرال مشخص نماید. وی با اشاره به آموزه های ادیان در پذیرش حقوق طبیعی انسان ها (ص 27)، تلاش می کند مشروعیت قانون برآمده از مردم سالاری را از درون خود بجوید و به منظور تضمین آن به هیچ نظام متافیزیکی و دینی متکی نشود.

وی با تفکیکی که بین دو سنخ از مردم، یعنی مخاطبان قانون و مؤلفان قانون، در مواجهه با دولت مردم سالار ترسیم می کند بیان می کند معتقد است که نظام سیاسی باید ب��ای وضع اخلاقیات سیاسی اقدام نماید و از شهروندان انتظار داشته باشند در قامت مؤلفان قانون، به منظور رسیدن به نفع عمومی در فعالیت های سیاسی مشارکت کنند. هابرماس خاطر نشان می کند که هرچند پیشتر صرفاً با نظام های متافیزیکی یا دینی می توانستند مؤلفان قانون را شکل دهند، امروزه خود «عملکردهای مردم سالارانه نیز موجب نوعی پویایی سیاسی منحصربه فردی» می شوند. (ص 32) هدف در نهایت آن است که شهروندان قوانین وضع شده توسط نظام مردم سالارانه را خارج از بستر تاریخی هر ملت بپذیرند که البته تصریح می شود رسیدن به این مطلوب، صرفاً با فرآیند شناختی ممکن نمی شود و باید به جهت گیری عمومی بافت اخلاقی فرهنگ بدل شود. (ص 34)

هابرماس با ارجاع به تجربه های تاریخی نشان می دهد که چگونه ممکن است هم بستگی اجتماعی فروبریزد و تحلیل هایی در توجیه این فروپاشی آن را به کنه عقل مدرن می کشانند (پست مدرن ها) و ممکن است به این نتیجه برسند که صرفاً به وسیله توجه دینی به سرمنشاء متعال است که می توان هم بستگی از دست رفته در دوران مدرن را بازیافت؛ چیزی که مسلماً هابرماس با آن مخالف است. ولی راه کار هابرماس مشخصاً ارجاع به خود فرآیندهای مشارکت مردم سالارانه است که از طریق آن، فلسفه در قامت رسالتی اجتماعی خود باید به تعمیق عقل بپردازد و رابطه خود را با دین، به عنوان موضوعی اساسی برای تأمۀل، مجدداً احیا نماید.

در ادامه هابرماس طی سه ضمیمه توضیحی با مسأله رابطه عقل و وحی در دین و تفکیکی که فلسفه میان وضع سکولار به عنوان مدعایی برای همه مردم و بحث های دینی به مثابه حقایقی وابسته به وحی قائل می شود، درصدد است تا نشان دهد که جایگاه فلسفه و دین در یک جامعه سکولار باید چگونه باشد تا در نهایت نقش شهروندان دین دار و غیردین دار را در جامعه لیبرالی مدنظر خود مشخص کند: نتیجه ای که او در نهایت می گیرد آن است چنانچه شهروندان دین دار در یک سیاست سکولار نمی تواند دین را به عنوان مقوله پیشاسیاسی در نظر بگیرند، شهروندان سکولار هم نمی تواند تمامیت دین را نفی کنند و باید بپذیرند دین داران می توانند با زبان بخصوص اجتماعات دینی خود، بخشی از مشاجرات عمومی مطرح در عرصه عمومی را پاسخ دهند.

2.2. راتزینگر: آنچه جهان را گرد هم نگه می دارد.

راتزینگر ولی بحث را از موضع دیگری آغاز می کند و مشابه متألهان دیگر، انسان شناسی را نقطه شروع در نظر می گیرد. وی با اشاره به بحران هایی که در زمینه اخلاقیات پیش آمده، از تلاش برای اعاده اخلاق در جامعه سخن می گوید و از رسالت علم و فلسفه در توجه به انسان بماهوانسان سخن به میان آورد. وی در تلاش برای یافتن نقاطی در سیاست می گردد که حاصل اجماعی غیرمقطعی انسان ها پیرامون آنان باشد، تا موضوعاتی مثل بی بصیرتی و یا بی انصافی رأی دهندگان نتواند آنان را مورد مناقشه قرار دهد، برای مثال چنانچه درباب حقوق بشر اتفاق افتاده است. (ص 55) وی در ادامه به دنبال سازوکاری می گردد که از طریق آن بتوان خود پدیده قدرت و اشکال جدیدی که از آن ظرف صدسال اخیر به وجود آمده است را تبیین کند و از طریق این تببین، راهکاری برای کنترل قدرت بدست آورد.

وی با اشاره به چند مثال کلی نشان می دهد که چگونه اعتماد انحصاری چه به دین و چه به عقل برای کنترل قدرت ناکارآمد شده است: زمانی که ترور به واسطه تعصب دینی باعث ترس در جامعه می شود و هنگامی که بمب اتم به عنوان دستاورد عقل می توان کل حیات بشر در زمین را به مخاطره اندازد. بنابراین به نظر می رسد که هیچ کدام از دوگانه عقل و دین نمی توانند به تنهایی بحران هنجار اخلاقی مورد اتفاق به عنوان شالوده پیشاسیاسی مدنظر را تامین کند.

راتزینگر عواملی که باعث بروز چالش در هنجارهای اخلاقی را سبب شده است را اولاْ کشف آمریکا و ثانیاْ ظهور انشقاق در خود عالم مسیحی می داند؛ عواملی که هر کدام باعث فروپاشی نظام هنجاری عالم پیشین شدند. راه حل اولیه مسیحیت برای این چالش ها بهره گیری از ایده قانون طبیعی به عنوان پشتوانه ای عقلانی متکی به طبیعت انسانی بود؛ ایده ای که البته به دلیل غلبه نظریه تکامل و روشن شدن نقاط غیرعقلانی طبیعت دیری نپایید و از اساسا خود بی اعتبار شد. ولی به هرترتیب نیاز به رسیدن به اتفاقی فراقانونی هنوز احساس می شد که خصوصاْ حقوق بشر تجلی توافق و اجرایی شدن این نیاز بود.

راه حلی که راتزینگر در نهایت برای برون رفت از این وضعیت پیشنهاد می کند بهره گیری از چشم اندازی بین فرهنگی است. ولی با نشان دادن عدم همسانی و یکنواختی هر دو ایده دین و عقل نتیجه می گیرد که هیچ کدام جهان شمولی اولیه را در اختیار ندارند و حتی برخلاف تصور اولیه «یک قاعده عقلانی یا اخلاقی یا دینی که تمام جهان را فرابگیرد و همه اشخاص را متحد سازد وجود ندارد یا حداقل در حال حاضر دست یافتنی نیست» (ص ۶۷)

راتزینگر در نتیجه گیری نهایی خود خاطرنشان می کند که چنانچه سابقه آباء کلیسا نیز دلالت بر آن دارد دین همواره از نورالهی عقل به عنوان نیروی کنترل شده بهره گرفته است و در عین حال نسبت به آسیب های آن نیز آگاه است. بنابراین بیان کرد که وابستگی ضروری بین عقل و دین باید برقرار کرد تا هر دو در دادوستدی دائمی یکدیگر را پالایش و ویرایش کنند و بتوانند از دستاوردها هم بهره گیرند. راتزینگر مدعی است که این امر تنها در فضایی بین فرهنگی ممکن است که محقق شود و در عین حالی که امر��زه رد عقلانیت سکولار غربی و ایمان مسیحی در همه فرهنگ دیده می شود ولی باید فضا را برای عرضه همه گفتمان های دینی و عقلانی به روی غرب گشوده شود.

3. نقد و بررسی

به طور کلی به نظر می رسد که هرچند گفتگوی این دو متفکر تراز اول جهان مختصر است حاوی نکات بسیار بدیعی در زمینه امر سیاسی است؛ خصوصاً با توجه به اینکه به شکل انضمامی به مسائلی می-پردازد که مبتلابه بسیاری از کشورهای جهان است. نتیجه ای که از درنهایت می توان از کتاب بدست آورد نیاز به تعامل دائمی عقل و دین در فضایی بین فرهنگی و عملاً تقلاهایی که برون حذف هر یک از این دو ��قوله مطرح شده است پیشاپیش محکوم به شکست خواهند بود: در عرصه عقل عملی از سویی نه می توان از کارکردهای حیاتی دین به عنوان یک عامل اساسی وحدت بخش در جامعه صرف-نظر کرد و از سوی دیگر نیز نمی توان به عقلانیت س��ولار بخشی از جامعه که تعهدی به آموزه ها دینی ندارند بی عنایت بود. در واقع هر دو این اطراف این منازعه باید در حل مشکلاتی که نوع بشر در مواجهه با آن قرار دارند بیاستند و هر یک مسئولیت خویش را به نحو احسن ایفا نماید. هرچند که نظریه هابرماس درنهایت به دنبال تحقق یک جامعه سکولار است که در نظر او ورای دین داری و غیردین داری است؛ نظریه راتزینگر طرحی کلی در این حوزه بیان نمی کند که البته این اقتضای رویکرد الهیاتی اوست که منتج به صورتی قطعی از سیاست نخواهد شد. ولی به طور کلی گویا اجماعی بر بهره گیری از ظرفیت هر دو طرف جدال برای حل مناقشات دیده می شود. -

الكتاب عبارة عن ورقتين قدمت من هابرماس وراتسنغر للحديث عن فكرة الدين والعلمانية من حيث العمل والتطبيق, خصوصاً في ورقة راتسنغر, الكتاب يتلخّص في فكرة هابرماس وهي الحديث عن ما "بعد العلمانية" وهي دخول رجال الدين في السجال العلمي مرة أخرى بعدما أثبتت العلوم الإنسانية مدى أهميّة البعد الأخروي في جميع نواحي الحياة وذلك يتضمّن البحث الفلسفي والعلمي, قبل نقاش الورقتين كان للمترجم القدير حميد لشهب تقديم طويل للكتاب مقارنة بصفحاته, يؤكد فيها على فكرة تغالط النظرة السطحيّة للنظر إلى التنوير الأوروبي "الخطأ الكبير الذي سقطنا فيه هو أننا فهمنا بأن الفكر التنويري الأوروبي لم يحاول محاورة الفكر الكلاسيكي واللاهوتي, بل أعلنا بكل جدية وبكل اعتزاز بأنهما قد تجاوزاه, وبأن الحاجة لم تعد قائمة للإهتمام به. والحقيقة أن كبار الفلاسفة الغربيين في عصر التنوير وخصوصاً الجرمانيين منهم, اهتموا بجدية بموروثهم المسيحي ودرسوه بعناية فائقة, قبل أن يأخذوا منه موقفاً مناوئاً أو مناصراً". وبعدها ورقة هابرماس بعنوان (الأسس القبل السياسية للدولة الديمقراطية القانونية), سأذكر منها فكرتين:

يقول "إنّ الدولة الليبرالية غير قادرة على إنتاج الشروط التحفيزية انطلاقاً من استمراريتها العلمانية. من الأكيد أن أسباب مشاركة المواطن في تشكيل وجهات النظر والإرادة السياسية تتغذى من أشكال حياة أخلاقية وثقافية. ولكن للممارسات الديمقراطية ديناميكية سياسية خاصة بها. وفقط دولة حق دون ديمقراطية, كما تعودنا عليها في ألمانيا, هي التي يمكنها أن توحي بجواب سلبي عن سؤال: إلى أي حد يمكن لشعوب موحدة في دولة تضمن حرية الأفراد أن تستمر في الوجود دون حبل رابط بين هؤلاء الأفراد يسبق هذه الحرية؟", هابرماس يؤكد هنا على أساسيّة المشترك التاريخي الثقافي بين الشعوب في تكوين أي دولة لا تكون الديمقراطيّة منهجاً لها. وفي هذه النقطة ملاحظة جميلة إن عكست الجملة, أنه من الممكن تكوين دولة تقوم فقط على "فنّ المشترك" بين الأفراد دون هوية تسبق الحريّة ولفتحي المسكيني كلام يضاف في هذه النقطة في كتابة الهوية والحرية. الفكرة الثانية هي مطالبة هابرماس بأن يكون الدين هو حالة فرديّة من الممكن أن تستمدّ تصوّرها من الجماعة دون أن تكون لها سلطة فرض على أي فرد"من اللازم على الوعي الديني أن ينجح في صيرورة اندماجية في المجتمع الحديث, ويعتبر كل دين في الأصل (تصوراً عن العالم) أو (فهماً عقائدياً) يطالب بحقه في السلطة لكي يبني شكلاً من أشكال الحياة في كليته. لكن على الدين أن يستغني عن هذا الحق والحق في احتكار التأويل وتنظيم الحياة الشامل نظراً لشروط علمانية العلم ومحايدة سلطة الدولة والحرية الدينية الشاملة. وقد انشطرت حياة الجماعة الدينية عن محيطها الإجتماعي مع التقسيم الوظيفي للأنساق الجزئية للمجتمع. ويختلف دور التابع لجماعة دينية ما عن دوره كمواطن ما في المجتمع", السؤال كقارئ هنا: إلى أي مدى يمكن أن تجد هذه الفكرة أصالة لها في الفكر الإسلامي؟

الورقة الثانية هي لراتسنغر بعنوان "ماذا يوحّد العالم, أسس الحريّة الما قبل السياسيّة لدولة حرة", يهتم أكثر بالجانب الأخلاقي في حديثه يقول "في سرعة التطور التاريخي حيث نعيش يظهر لي أن هناك عاملين أساسيين لهذا التطور: من جهة هناك تكون مجتمع دولي لا بد للقوى السياسية والإقتصادية والثقافية من أخذه في عين الاعتبار, لأنه يمس ويدخل في كل ميادين الحياة. ومن جهة أخرى تطور إمكانيات الإنسان للفعل وللهدم, التي تفرض طرح سؤال المراقبة القانونية والأخلاقية للسلطة. ولهذا السبب يعتبر التساؤل حول كيفية اتفاق الثقافات المختلفة التي تعيش في مجتمع ما من الأهمية بمكان, وهي أسس تقوده هذه الثقافات في الطريق الصحيح, في طريقة العيش معاً وتأسيس شكل قانوني مشترك لنظام السلطة المشتركة التي تقودهما", نعود هنا مرة أخرى إلى "فنّ المشترك" والتي أرى هنا أن الفكرة تكتسب أهميتها يوماً بعد يوم, بالنظر إلى السير التاريخي للعلاقة بين الدولة والفرد, فالهويّات بدأت تفقد حيّزها النظري والعملي في مستوى تعريف الفرد لنفسه, وبدأت بدلاً من ذلك تتحوّل إلى تعبئة تفرضها القلّة المتحكمة لتحريك الفرد في الدفاع عن أهدافها. على عكس الفرد الآن تماماً, الذي يجب أن يبحث عن ذاته في ظل هذا التداخل العالمي وأن يعود إلى هويته عودة ما بعد تاريخيّة إن صح التعبير -

جدلية العلمنة، العقل والدين

على رغم حجمه الصغير إلا أنه ثقيل موضوعاً، تضم صفحات الكتاب الثمانين كلمتين ألقى أولاهما الفيلسوف الألماني الشهير يورغن هابرماس، وألقى الأخرى البابا المستقيل جوزف راتسنغر – عندما كان كاردينالا ً -، وكان هذا في سنة 2004 م في الأكاديمية الكاثوليكية بميونيخ، كلتا الكلمتين تناقش العلاقة بين العلم والدين، إنه الصراع الدائم، كلتا الخطبتين برأيي معقدة، وتحتاج قراءة متعمقة، ومقدمة الكتاب التي وضعها المترجم (حميد لشهب) جميلة ومفيدة جداً للقارئ في التعرف على ما أسماه الجناح الجرماني للفكر الغربي، وكذا نبذة عن موضوع الكتاب. -

إذا جاء هذا الكتاب قبل فترة كان قد أغناني عن الكثير، ففي هذا الموضوع كان عنوانُ بحث لي بأول فصل في الجامعة، العلاقة بين الفلسفة والدين

الكتابُ صعب، ويحتاجُ لقراءةٍ عميقةٍ متأنيّة على الرغم انني اخترتُ له وقتًا من أكثر الأوقات التي تحوي هدوءا وهو بعد الفجر إلا أنني واجهتُ صعوبة في فهمِ بعضِ مُراده، خصوصا رسالة هابرمسان

كتاب يستخق القراءة ولكن بتروي ولا يمنع من قراءة ثانية له -

A clearly written, quality book

-

Bastante interesante, sobre todo la postura de Ratzinger.

-

An unholy alliance between Critical Theory and... the Vatican? If only.

Habermas frequently teeters on the edge of sheer banalityWhen secularized citizens act in their role as citizens of the state, they must not deny in principle that religious images of the world have the potential to express truth. Nor must they refuse their believing fellow citizens the right to make contributions in a religious language to public debates. Indeed, a liberal political culture can expect that the secularized citizens play their part in the endeavor to translate relevant contributions from the religious language into a language that is accessible to the public as a whole.

Wait, what did you just say? Let's try and be nice to each other - when possible.

The contribution of the then-future (and now former) Pope Ratzinger is hardly more substantial.

I agree that there should be more dialogue between believers and non-believers, but 'dialogue' ought to mean more than anodyne expressions of good will. For all the formidable intellect and erudition of these two men, that's basically all this book is. Say what you will about Adorno's hysterics, if he'd ever co-authored a book with a pope, you can bet it would have been a lot more interesting than this. -

يبحث الكتاب العلاقة بين العلم من جهة والدين من جهة في المجتمع الغربي، وتأثير ذلك على العالم، ويحاول كل من راتسنغر (رجل دين مسيحي كاثوليكي) و هابرماس (فيلسوف ألماني)، إيجاد تصالح بين الدين والعلم

ويخلص الكتاب في فكرة وهي: أنه لابد من تصالح بين العقل والدين، وخضوع الأول للمزيد من الإرشادات والتوجيهات من الثاني، ولابد من المزيد من التتطبيب المتبادل لبعضهما البعض، والاعتراف المتبادل ببعضهما البعض

وعن هذه الحاجة يُعبّر الفيلسوف الألماني هابرماس قائلًا: "وهكذا يظهر اليوم من جديد صدى نظرية تؤكد بأن الدين وحده هو الذي يمكنه أن يساعد الحداثة (الم��تكسّرة)، بتأسيسها على أساسٍ متعالٍ، من أجل إخراجها من المأزق الذي توجد فيه. "

ويختم راتسنغر (أحد أعمدة الكاثوليكية الاوروبية) البحث بخلاصة رأيه أن العقل والدين بحاجة لبعضهما بشدة، وبتحذيره من عدم استماع العقل للدين وتوجيهاته، فنجده يقول: " لقد رأينا بأن هناك نوعًا من المرض في الدين، وهو مرض جدّ خطير، يدفع بالضرورة إلى استعمال الضوء الإلهي للعقل كهيئة مراقبة!!.. ويتضح بأن العقل نفسه (وهو شيء لا تعيه الإنسانية اليوم) مصاب ببعض الأمراض لا يقل عن نظيره في الدين، بل يمكن اعتباره أخطر بكثير!! (السلاح النووي، صنع البشر). لهذا السبب يجب على العقل كذلك أن يُقاد من جديد إلى حدوده، ويكون مستعدًا للإنصات تجاه الوحي الديني للإنسانية. وإذا استقلّ العقل نهائيًا ورفض هذا الإنصات، فإنه يُصبح هدامًا". وهكذا يتناول البحث هذه العلاقة ويطرح المزيد من التساؤلات حول مستقبل البشرية والعالم أجمع، وليس فقط المجتمع الأوروبي، وعن مستقبل العلاقة بين الدين والعقل، وأثر هذا على المجتمع والأفراد -

الكتاب عبارة عن ترجمة لحوار بين الفيلسوف الألماني يورغن هابرماس والقس الكاثوليكي الألماني جوزيف راتسنغر، كان الموضوع حول تحديد سلطة العقل والعلمانية من جهة وبين سلطة الدين في أوريا خاصة والعالم عامة، بدأ المترجم بمقدّمة لا بأس بها شرح فيها طبيعة الصراع بين العلم والدين(ممثّلا بالمسيحية) وتفوّق العلم، وبيّن ضرورة فرملة الدين لتسارع العلم بهدف الحفاظ على إنسانية البش��، الهدف من الترجمة حسب المترجم هو إسقاط هذا الحوار الراقي في عالمنا الإسلامي الذي يعيش واقع مشابه جدّا لحالة أوربا قبل النهضة.

بدأ النقاش بطرح الفيلسوف هابرماس الذي لا يمكنني الحكم عليه لأنني صراحة لم أفهم أغلبه نتيجة كثرة المصطلحات المعقّدة والترجمة الحرفية التي لم تساعد، أما طرح القس راتسنغر فقد كان أكثر تنظيما ووضوحا حيث نظّم طرحه في نقاط محدّدة، أوّلا ذكر العلاقة بين القانون والسلطة وضرورة خضوعها له لا العكس، ثم حاول الوقوف في موقف وسطي بين العقل والدين حيث دعا إلى ضرورة تحديد الدين للعقل من انزلاقاته الخطيرة كالقنابل النووية والإستنساخ العشوائي وكذلك تحديد العقل للدين المتطرّف بصفته مغذّيا كافيا للإرهاب فكريا، ثم تناول إشكالية التنوع الثقافي في العالم وعلاقته بالأديان كدافع كافي للبحث عن قانون أخلاقي شامل لمختلف الثقافات، خرج في النهاية بخلاصة ضرورة توسيع العلاقة بين العقل والدين وضرورة التطبيب والتطهير والنقد المتبادل بينهما. -

نظرا للصراع القائم دوما بين العلم والدين، هذا كتاب يبحث في المفاهيم، محاولة لإعادة العقل والدين ضمن إطارهم دون مغالاة هذا عن ذاك.

دعوة لتجاوز مرحلة الخوف من النقد، من أجل التدقيق في تراثنا الديني، واعيين أن العلم لا يملك الحقائق المطلقة، انما موضوعيته في عدم يقينه وفي قدرته الدائمة على التشكيك.

موضوع النقاش في الكتاب، مأخوذ من مناظرة بين "يورغن هابرمس" و "جوزيف راتسنغر" تحت عنوان: الأسس الأخلاقية ما قبل السياسية للدولة الحرة. -

A fine little book. Jürgen Habermas and Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (later Benedict XVI) met in Munich in 2004 to discuss "the pre-political moral foundations of a free state." Roughly translated, this means they were discussing whether a democratic society requires religion. Their presentations are collected in this book. Habermas's answer to the question is a cautious no; Ratzinger's is a cautious yes. No surprises there. Both, however, argue that religion must be allowed to play a role in the democratic, pluralistic, and (ideally) rational public sphere. Here follows my somewhat free interpretation of their remarks.

Habermas concedes that the quest for rationality poses a difficulty for a free society. The Enlightenment dream of an entirely rational (and thus free) secular society turns out to be problematic. For the truly free state cannot compel its citizens to be rational, and furthermore, rationality itself is based on prerational commitments. However, Habermas suggests that this problem fades if we see rationality as a procedural and open-ended rather than a substantive and absolute affair. Rationality emerges when all aspects of the state are under the rule of law and all constituencies in the state are free to deliberate together on the law. The results of this communicative rationality may not be perfect, but they are by definition universally authoritative, and members of the state find freedom in the rationality of the procedure. Habermas then argues that this form of communicative rationality must include, by definition, religious believers. The religious person cannot claim singular authority in the state because he relies on revelation, which is not universally accessible, for truth; at the same time, however, the secular state cannot legitimately exclude religious insight from the discussion, for all reasonable people ultimately derive their beliefs from semiprivate sources. Priests must not dictate, but neither may philosophers; neither has a monopoly on reason in the modern world. Reason only happens when everyone can come together, when every source of wisdom can contribute to the common wisdom.

Ratzinger points out what I see as a significant weakness in this model: the modern world is not limited to the West. Yet since the middle of the twentieth century, most of us in the West have claimed that certain of our values are universally valid and accessible to reason -- human rights. On a Habermasian account, that claim is only true if everyone in the world is participating in a constitutional state. Obviously, no such global, constitutional, deliberative state exists. And while broad agreement exists about certain human rights, many cultures disagree significantly about the specifics. Ratzinger argues that we are therefore forced to make claims about substantive rationality (or absolute private revelation) after all, or else lapse into agnosticism about international morality: "the rational or ethical or religious formula that would embrace the whole world and unite all persons does not exist; or, at least, it is unattainable at the present moment" (76). The upshot? Ratzinger wants us to recognize our limitations in both reason and religion, both within the West and in our relations with other cultures. He wants "an attempt at a polyphonic relatedness [...:] so that a universal process of purifications (in the plural!) can proceed. Ultimately, the essential values and norms that are in some way known or sensed by all men will take on a new brightness in such a process, so that that which holds the world together can once again become an effective force in mankind" (79-80). This is remarkably close to Habermas's position.

The key difference between the two men, I think, is that Ratzinger thinks we must often forge ahead and act on our commitments even in the absence of the circumstances making for rationality. He agrees with Habermas that communicative rationality is crucial; he just doesn't think it is always possible, even -- or perhaps especially -- in the modern world. -

الكتيب عبارة عن مناظرة دارت بين يورغن هابرماس و البابا بنديكت في اطار جدلية العلمانية بين العقل و الدين،حيث يعرض هابرماس صورة للواقع أكثر مما يتناول طبيعة العلاقة بين العقل و الدين في العلمانية حيث ينطلق من مفاهيم يراها علمية واقعية تعطي غطاء تبريرا لاستمرار العلمانية بشكلها الحالي،و يضفي عليها صفة الانسانية التي تنتزعها من أي جذور غربية لها لتكون نهج عاما للانسان بغض النظر عن ثقافته و انتماءه و حضارته.

يتفق البابا بنديكت مع هابرماس في ضرورة اللجوء للعقل و لكنه يخالفه في هيمنة العقل و تحييد الدين الذي يراه ملجأ يهرب اليه الانسان عند تطرف العقل،هو لا يدعو بطبيعة الحال إلى القضاء على العلمانية و احلال الدين مكانها بقدر ما يدعو إلى اعادة صياغة العلاقة بين الدين و العقل في اطار العلمانية نفسها،يركز البابا على منشأ العلمانية و يؤكد على ضرورة احترام رؤى الحضارات غير الغربية في تعاطيها مع هذه العلمانية التي من حق هذه الحضارات و شعوبها الأخذ بها أو تطويرها وفق ما يلائم واقعها الحضاري أو حتى رفضها تماما. -

سيقول لك احدهم اذا حدثته بمثل هذه العناوين بانك شخص بطر وتبحث عن ترف فكري لتزجي به وقت فراغك سنجيب بان هذا الموضوع قضية مصيرية ليس لامة بعينها ولكن للعالم اجمع اذ ان خطورة المنزلق الذي تهوي اليه البشرية اليوم يعود بالاساس الى هذه العلاقة " العقل والدين "

الفيلسوف يورغن هابرماس يطرح اشكالية في الدولة الديمقراطية الا وهي كيفية ضمان التزام المواطنون اخلاقيا تجاه بعضهم البعض في مجتمع علماني حداثوي لايستند الى قيمة مطلقة والاخلاق فيه نسبية تعاقدية نفعية ويعرض الامر باسلوب فلسفي لينتهي بذكر ان هناك صدى لنظرية تعول على الدين كحل وحيد للاخذ بيد الحداثة المتكسرة واخراجها من المأزق.

يذكر في المقابل البابا بينيديكت السادس عشر ( والكتاب اصلا تفريغ نصي لحوار بينهما ) بان القانون هو تعبير عن العدالة ، والحرية دون قانون هي فوضى ،و ان ضمان المشاركة الجماعية في وضع القانون هو اساس جوهري لنظام ديمقراطي سليم ، لكن الاغلبيات يمكن ان تكون عمياء وجائرة لذا فأن مبدأ الاغلبية يطرح مشكل الاسس الاخلاقية للقانون وعليه احتاج القانون الى صيغة لحقوق الانسان وهذه الحقوق هي قيم بذاتها ناتجة عن الوجود الإنساني ذاته فهي بذلك تحتاج الى مسوغ اخلاقي يبررها والا فلا قيمة لها من منظور مادي بحت، هكذا يستنتج حاجة العلمانية للدين وكذلك الدين بحاجة للعلمانية حتى يتكامل برأيه.

الكتاب قصير ممتع ينفع كمقدمة لفكر الفيلسوف العملاق هابرماس وريث الفلاسفة الالمان العظام كهيجل وماركس و هيدجر وكانت ونيتشه و فرويد وهو كما اسلفت يتناول موضوع يتعلق ببقائنا كجنس بشري على هذا الكوكب اذ ان اشكالية الحضارة العلمانية هي خلوها من القيمة والمطلق لذا هي تتبنى فلسفة براجماتية نفعية همها الاول والاخير اللذة والاستهلاك الذي ادى الى تفاقم الكارثة البيئية وتكالب الامم على سباق التسلح الذي ينذر بنهاية مرعبة للبشرية، لذا يطرح المتحاوران الدين كوسيلة لانقاذ المجتمعات من العدمية التي ارستها الفلسفة المادية، وهما لا يتغاضون عن المشاكل التي افرزتها التجارب الدينية ولكن يتبنون حلًا وسط بين العقل والدين -

Un diálogo interesante sobre la necesidad de la razón en comunidades altamente religiosas y viceversa.

El concepto de solidaridad ciudadana, que menciona Habermas, me pareció sumamente interesante en la busqueda de una sociedad plural.

En cuánto a la visión de Ratzinger, me sorprendió su mesura y el reconocimiento de la necesidad de un Estado laico, además de su ahínco en no dejar de lado el pensamiento oriental y superar el eurocentrismo.

Sin duda este diálogo me acerca al pensamiento de Habermas y me aleja de lo perspectiva fútil que tenía sobre Ratzinger (Benedicto XVI) -

هو فين الكتاب ؟؟؟؟؟الكتاب 90 صفحة منهم 70 صفحة تقديم وتمهيد

-

En un mundo en el que los prosélitos del cientismo más estrecho, y sus análogos fundamentalistas religiosos lanzan sus poderosas proclamas arrogantes, algunos siguen intentando establecer una conversación virtuosa. Habermas, el más anciano de la escuela de Frankfurt, y el que sería líder del cristianismo católico, sorprenden con una firme convicción capaz de abrirse a la comunicación fértil. Es esperanzador ver cómo lo más profundo de las exigencias éticas de una racionalidad filosófica (no cómoda ni automáticamente) es capaz de llegar a más acuerdos que desacuerdos con una religiosidad profunda, sincera y amplia de miras. La una filosofía práctica-emancipatoria y un cristianismo sincero (aquel en el que dios es antes amor que potestas), siempre aspiran a una cierta universalidad que tarde o temprano se juega en el terreno político, pero jamás impide a las mentes más abiertas y brillantes el ver como esta universalidad no solo no casa bien con la intolerancia o el totalitarismo, sino que incluso la rechaza por principio.

Pasen y vean... -

Buen libro, aunque muy burdo como aproximación a la escuela de Frankfurt. Es la primera vez que leo a Habermas y no es sencillo. El punto de vista de Ratzinger me pareció excepcionalmente claro, de manera que no usa un lenguaje para tontos ni es laberíntico como de ratos fue Habermas. De todas maneras es bastante lo que aporta este libro tan pequeño, sobretodo como material de debate posterior.

-

الكتاب عبارة عن ترجمة لحوار بين الفيلسوف الألماني يورغن هابرماس والقس الكاثوليكي الألماني جوزيف راتسنغر، ، يبحث في المفاهيم، محاولة لإعادة العقل والدين ضمن إطارهم دون مغالاة

و يعتبر كتاب ثقيل علي المبتدئين وغير المهتمين . -

Desconocía ésta faceta de Ratzinger.

En general es un libro fácil e interesante. -

Ratzinger comes off as much more radical than Habermas. In my reading at least.

(Though I should probably re-read it, haha.) -

Read in honor good ol Benedict. This was a great little book, an argument between Ratzinger and Habermas about the pre-political makeup of the state. I think that Habermas was able to confirm in his warning to other atheists a suspicion I’ve had. He (as a rationalist) said to post-modernists that they have to be careful lest in their post-modernism they become an “easy prey” for “theology.”

In different words, I feel like the cultural movements of our day create unique and exciting opportunities for the Church to speak with greater power than it has been even while not holding a place of dominance. Even with the problems that the new culture brings, the opportunities for the gospel to speak in creative ways to the current cultural confusion seem endless if we hunker down and do the work, live lives genuinely modeled after Christ, and continue in patient conversations with unbelievers -

تحاول الرسالة أن تعطي فكرة عن ما وصبت إليه العلاقة بين العلم والدين في المجتمعات الحديثة.

-

This was less a debate than, as the introduction says, an short summation by two thinkers of their thoughts. One secular neo-Kantian, Jurgen Habermas, and one Roman Catholic (to be Pope) Joseph Ratzinger about the necessity of society's two halves, secular and religious to learn from one another.

Both recognize that the organization of society is in some sense what religion excels at; the mapping of human organization and understanding to solidarity and justification of a statehood. They both also recognize that religion in some sense goes too far in organization; that there are pathologies that religion can force because it is mobilized too far in a particular way.

This gets at the heart of human eusociality. We want to belong. We are made to calibrate with one another. This touches on areas that reason (qua secularization) cannot reach. Societies do need to account for the non-reasoning part of people. People need to have calibrating experiences to be at the same level with one another. Instead, we have ultra-rationalism in the form of markets engineering approaches that do not calibrate people, but instead, allow people dominance and agency over one another. Having a point outside of reason, one that signals for people direction is the function of religion that both thinkers believe secular society can benefit from.

What's interesting is that historically, religion and culture were the same. It is only through the split offered by reason as a different mode of organization that splits religion and culture apart. A secularized religion, seems to be the synthesis with which both thinkers offer, although the book merely ends with Pope Benedict (Joseph Ratzinger)'s essay.

Short book, but interesting. A quick read. -

Lacking any real frame of reference, this being the first thing I've read by Habermas or Ratzinger or on the subject of secular v. religious politics, I have to defer any serious critique. I'll say this though: this book reeks of respectful, perhaps hollow political posturing. It reminds me of the kind of tepid discussion that happens between two heads of state making the diplomatic rounds -- or at least the way the news portrays that sort of thing. Really lacking in polemical thrust. Each man comes across profoundly reasonable, not even approaching the dogmatic feelings I'm sure each is harboring. So the tussle is more of a tango, probably because the stakes for sustainable democratic politics are higher than ever, given the ideological and physical threat terrorism poses to the West. Habermas and Ratzinger take a pragmatic approach, in the sense that consensus is pragmatic. They specifically confront the issue of whether Western secular democracies have the foundations to sustain peace and some common moral direction. Each insists that secular and religious communities must go beyond acceptance and collaborate in order to maintain their common interests, which are integral to the future of successful global politics. It's all somewhat vague, and no one proposes how the problem of religiously inspired terrorism can be diffused by political means (I know that's a lot to ask, but they could at least mull it over). In fact they virtually omit terrorism from the discussion. I'd like to see Habermas and Zizek engage in a similar debate, no holds barred.

-

THE TRANSLATION OF THIS BOOK GETS A MILLION POINTS OFF FOR REPEATEDLY USING THE WORD "SOCIETAL." THE WORD IS "SOCIAL."

Otherwise, this book is what you'd expect. Habermas' piece is unfortunately disorganized and underdeveloped. Here's my favorite sentence from his essay: "In my view, weak suppositions about the normative contents of the communicative constitution of socio-cultural forms of life suffice to defend a non-decisionist concept of the validity of law both against the contextualism of a non-defeatist concept of reason and against legal positivism." Who else could write that sentence?

Ratzinger's piece is both more interesting and more disagreeable than you'd expect. He can talk the multicultural talk. But I get the sense that there's an ideological medievalism at work in his argument, particularly in some of his comments about evolutionary theory as the final collapse of the idea of "natural law" in secular society, in his reductionist conception of science as unconcerned with or unaware of the ethical dilemmas of its discoveries, and in the conflation of the critique of instrumental rationality with rationality itself. I'm afraid he would endorse the old idea that an atheist can't be moral (despite numerous examples to the contrary...). -

It's remarkable that this dialogue (between the leading living neo-Marxist and a future pope) exists. Unfinished. It was just an evening's thoughts between the two.

There's a real gem of shared insights about tolerance, the mutual purification of reason and religion, and public life in the postmodern world.

Habermas shows that the democratic constitutional state needs to draw on its citizens' religious visions for coherence and purpose. And that secular philosophy must translate those visions into neutral concepts available to people of different beliefs.

Ratzinger picks up on Habermas' failure to define the actual purposes of law. He talks about how reason and religions (in the plural - he is sensitive to the need to take different cultures more seriously than the West thus far has) both illustrate something of who the human is. Only a humanism derived from both, then, can properly tame powers - political, scientific, religious, and so on.

This dialogue, clocking in at a mere 60 pages, is a brief hint of more work to be done. It's well worth the quick (with Ratzinger, anyway; Habermas is dense German theory) hour or two needed to let it prod the mind. -

Dos grandes autoridades del mundo intelectual dialogando sobre lo humano, el estado pre democrático, la defensa de la persona, la solidaridad,la secularización, la razón y la fe, etc.

Varios hechos insólitos plasmados en la obra:

El encuentro de uno de los filósofos más importantes de la era moderna con uno de los principales pensadores de la iglesia católica; el resultado del diálogo, lo cual es insospechado y sorprendente incluyendo los diversos ángulos y divergencias; pero tal vez lo mejor es que haya quedado plasmado en este escrito.

Superó todas mis expetativas.

Imperdible para todo aquel buscador honesto de la verdad, que de entrada deberíamos de ser todos.

Me parece que los académicos e investigadores disfrutarán de manera especial este libro.