| Title | : | The Wife of Bath |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0312111282 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780312111281 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 320 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1372 |

The Wife of Bath Reviews

-

I wouldn’t want to be a medieval wife

Well I don’t want to be any sort of wife, but that’s beside the point! What I’m trying to say is that medieval womanhood wasn’t a good form. This wife was forced to marry at twelve years of age, twelve years of age, and since then has married five times; thus, she considers herself somewhat of an authority on marriage. And who can argue, she clearly has more experience than most:

Middle-English Version

"Experience, though noon auctoritee

Were in this world, were right ynogh to me

To speke of wo that is in mariage;

For, lordynges, sith I twelf yeer was of age,—

Y-thonked be God, that is eterne on lyve!

Housbondes at chirchė dore I have had fyve;

For I so oftė have y-wedded bee;

And alle were worthy men in hir degree."

Modernised Translation

"Experience, though no authority

Were in this world, were good enough for me,

To speak of woe that is in all marriage;

For, masters, since I was twelve years of age,

Thanks be to God who is forever alive,

Of husbands at church door have I had five;

For men so many times have married me;

And all were worthy men in their degree."

Her experience becomes her weapon; her sexual potency becomes a means for control. But, she has also been subjected to endless sermons of scripture and churchly didacticism, so she tries to use it to her advantage. And in this Chaucer provides a critique of the church. Almost everything the wife utters about religion is completely false: it is what she has been told by conniving churchman who wish to wield their authority for personal advantage. They twist the words of their bible to form their own patriarchal creed. They are the worse kind of churchman because they exploit their power and position of trust.

So when the wife innocently repeats such babble, it’s rather humorous. She becomes a pseudo-feminist as she refutes her society, but, ultimately, she continues to contribute to it. Admittedly, she doesn’t have much choice. She is a rather singular voice after all. She conforms to the idea of what the church saw as debased and immoral. Rather ironic isn’t it? What she needed to do was become something more potent, and really show the churchmen how manipulative they can be.

This is a good piece of literature, I always enjoy reading Chaucer; however, this edition has modernised the language. It has provided a translation. So, in reality, it doesn’t actually feel like Chaucer any more at all. For me this is a bad move, I like to read Chaucer in its original form with all its old spellings and archaic language even if it is difficult in places to follow. That’s part of the experience. I used an original quote at the start to demonstrate this. I don’t recommend this edition at all. At the very least, try an edition that has both versions. An original one you can read and a modern one for point of reference.

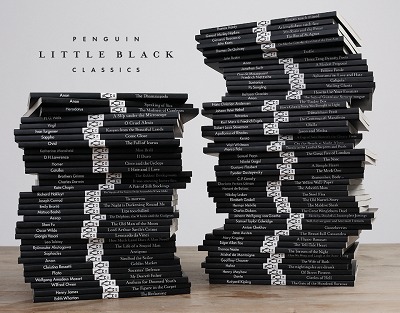

Penguin Little Black Classic- 28

The Little Black Classic Collection by penguin looks like it contains lots of hidden gems. I couldn’t help it; they looked so good that I went and bought them all. I shall post a short review after reading each one. No doubt it will take me several months to get through all of them! Hopefully I will find some classic authors, from across the ages, that I may not have come across had I not bought this collection. -

![[ J o ]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/users/1673171874i/4639825._UY200_CR4,0,200,200_.jpg)

Geoffrey Chaucer was an English 14th Century diplomat and philosopher amongst other things, though is best known for being a Poet and writing the Canterbury Tales. The Canterbury Tales were written during the 100 years war and tell of a group of pilgrims on they way to Canterbury Cathedral to visit the shrine of Thomas Beckett, with the prize being a free meal at an inn.

"You say it's torture to endure her pride

And melancholy airs, and more besides.

And if she had a pretty face, old traitor,

You say she's game for any fornicator."

Each Pilgrim has their own prologue and tale, and this one belongs to the Wife of Bath. This Little Black Classic is different to the usual Chaucer books in that this one has been translated to modern-day English, making it the perfect starting point for anyone who is looking to read some Chaucer but doesn't either known where to start or has been put off by the Middle-English language.

"True poverty can find a song to sing.

Juvenal says a pleasant little thing:

"The poor can dance and sing in the relief

Of having nothing that will tempt a thief."

The Wife of Bath's Prologue, as all the pilgrim's prologue do, contains information about the Pilgrim themselves at first, giving you a taste of their countenance and backstory. Then their tale is told, which in this case is an Arthurian tale of a misogynistic knight who, in exchange for his life, must find out what women truly desire. It is a tale that could have been written in this day and age, and it reminds us just how mediaeval our gender equality and ideals really are in some respects. Relevant, though it shouldn't be.

Blog |

Instagram |

Twitter |

Pinterest |

Shop |

Etsy -

I really liked the essays dealing with the content of the text, but Mr Beidler himself is rather pedantic for me, rambling on and on about the authenticity of this copy and that copy of the various manuscripts that still exist of this text. He seems to be really a hard-core hardcore Chaucer super specialist, giving background on the debates around the origins of the various manuscripts.

I see this edition is not linked to other editions of Chaucer's The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale, so I'm going to add that review in here as well. Apologies to those of my friends who have already read it in the past, but this Case Studies in Contemporary Criticism is actually a very good series.

***

Since there has been such a spate of reviews on Goodreads recently, attending to texts that contain the depiction of female masochistic tendencies, I decided to go all the way and go way back to the first text we know of in English that contains this, being Geoffrey Chaucer's Wife of Bath's prologue and tale.

Both the tale and prologue depicts violence visited upon women, and in the prologue, it is initially even welcomed by the woman, for love of the man inflicting the violence; but just like Ana in 50 Shades of Grey, Alison decided eventually that she didn't like it, and decided to reform her attractive, sexy fifth husband Janken into more couth ways.

Arriving at a definite stance on how to interpret the message or the character of Chaucer's Wife of Bath, is not an easy task. The Wife of Bath is probably one of the characters that there seems to be least agreement upon, in the entirety of English literature, or such has been my own experience when reading scholarly interpretation upon scholarly interpretation, in order to try and clear my own confusion as to exactly what it is that the Wife herself is saying, and moreover, what Chaucer is generally saying with his creation of the Wife and her Tale.

I have come to the conclusion that the Wife of Bath is at the same time an expression of anti-feminism, and to a smaller extent of pro-feminism, each in different aspects and contexts.

I was taken aback, when I read the Wife's Prologue originally, by the apparent (to me) misogyny in this work. It is quite easy to see the misogynist voice Chaucer is speaking with. In the Prologue to the tale, Chaucer seems to be mocking and satirizing a bossy, nagging wife - the kind of wife that most men dread and would find hard to handle.

Comments upon her from scholars seem varied; some praise her as the first feminist, though many feminists see past that and also see a male voice making a hateful parody of the female gender, and of wives in particular, but they also note and comment quite strongly upon the theme of violence weaved into this tale.

Chaucer does not paint a pretty picture of the Wife in her Prologue. She is shown as a liar and a cheat who does not hesitate to openly admit that she prostituted her body to her first four husbands for material gain, and used all manner of deceitful devices to achieve "mastery" over them.

From The Wife of Bath’s Prologue : (as translated)

"Deceit, weeping, and spinning, God doth give

To women kindly, while that they may live. *naturally

And thus of one thing I may vaunte me,

At th' end I had the better in each degree,

By sleight, or force, or by some manner thing"

(Just as a side note, it is interesting to note the use of the word "spinning" whereas Alisoun's occupation is that of a weaver.)

The latter quotation is just one example of the kind of self-revilement that goes on right through the Wife's own description of her relationships with her first four husbands, often extending the negative attributes of the Wife to the female gender in general.

To make matters worse, the wife openly admits that she did not love these four husbands, and often feigned lust just to gain more of an advantage over them.

The Wife as the product of a male construct is never more apparent than in her repeated mention of her own genitals. Over and over she mentions her own genitals (thereby objectifying the female as an object whose sole function is the sexual gratification of males) and how her husbands praised this part of her body. She also mentions how she could have sold it, (her vulva), but kept it for her husband instead (in the sense of a bargaining piece), which does seem to me to have strong overtones of suggesting that wives are little more than prostitutes.

What eyleth yow to grucche thus and grone?

Is it for ye wolde have my queynte allone?

Wy, taak it al! lo, have it every deel!

The playful tone of most of the passages in the prologue, in which the wife tends to contradict herself at times, suggests to me that they were written as entertainment largely for males, who in those times (The Canterbury Tales were thought to have been written around the 1380's) dominated the literate world.

This alone, would in my view be enough to establish a claim of this text being misogynist, albeit as a product, to a large extent, of the milieu that Chaucer found himself in.

However, one of the contexts in which I feel it is useful to view the Wife of Bath, is the phenomenon of Chaucer's criticism of the Catholic Church, that pervades the Canterbury tales.

From a historical background, the Black Death had not only opened the way for a stronger Bourgeoisie class, and for a stronger base in medieval society for property rights for women, (which was helped along by the fact that many males were absent/died during the Crusades) but it also weakened the grip of the Catholic Church, which was further weakened by the Western Schism, and which scenario set the stage for the Church Reformation which took place a bit later on in the course of history.

During the fourteenth century (Chaucer was born in 1343), the Catholic church was still very powerful, and many clergy abused their position of psychological power in order to gain temporal power, wealth, and it would seem, sexual/sensual gratification as well.

Chaucer seems to have been well aware of the various types of corruption that members of the Catholic institution was guilty of, from hypocrisy to avarice, to all sorts of clandestine sexual practices, which Chaucer hints at when describing the Friar, one of the Canterbury Pilgrims.

When, at the beginning of the Wife's tale, mention is made that:

"Wommen may go saufly up and doun.

In every bussh or under every tree

Ther is noon oother incubus but he, (referring to "holy" friairs)

And he ne wol doon hem but dishonour", one wonders if Chaucer is referring to the kind of sexual misconduct apparently practiced by the clergy in the 1300's- 1400's that Amanda Hopkins mentions in her article: "Sex, the State and the Church in the Middle Ages: An Overview".

According to a footnote in the above-mentioned article, "The evidence of medieval authors, Boccaccio and Chaucer among them, suggests that celibacy was not universally practiced by the clergy.

In an examination of legal records from the Paris area in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Kathryn Gravdal finds evidence of gang rape:

"These collective rapes seem to have been youthful sprees. Patterns in the records indicate, however, that when young clerics eventually became priests and rectors, they continued to practice sexual abuse and these constituted the second largest group of rapists brought to trial in the Cerisy court. … This finding corresponds to the figures Hanawalt and Carter have established for the clergy in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century England, where clerics constituted the largest group to stand trial for rape in the secular courts. The power and prestige of their office may have led them to commit sexual abuses with a certain regularity"

The implication of the above-mentioned research, that Chaucer might have been hinting at actual rapes being perpetrated by the clergy, seems so shocking to me, that I find it understandable that the allusion to "gang-rape by the clergy" in these passages was probably never entertained by critics like Louise O. Fradenburg, who assumes that the substitution of incubi by friars is merely a demystification, and Luarie Finke, who sees in it symbolism of changes to the economic structure of the medieval world.

The sexual activity of the clergy is especially ironic in view of the strong stance the Church officially took against the expression of any sexuality, whether hetero- or homosexual.

We jest in today's modern age about conservatives who decree that sexual intercourse is only admissible when it is vaginal heterosexual intercourse between married partners, in the missionary position, in the dark, and preferable partly clothed; but absolutely no joking: - this is exactly what the Medieval Catholic Church decreed. Any deviance from the above-mentioned, was punishable by having to do 'penances'; even, for instance, for the 'sin' of married heterosexual intercourse with the woman on top, or intercourse with the wife facing away from the husband.

The Pardoner who is one of the pilgrims in the Canterbury Tales, was one of the people who could gather money from the populace in order to gain pardons for such terrible crimes as, for instance, having intercourse in 'inadmissible' positions, or the even more unforgivable sin of actually enjoying it.

In view of the above and other hints throughout the rest of the Canterbury Tales, I think that a lot of what the wife says, is actually a parody of some of the negative attitudes the Catholic church held about women and marriage, and was just an additional but more subtle way in which Chaucer was criticizing the Catholicism of the day, along with his more obvious digs at the Pardoner, Summoner, Friar and Prioress who take part in the Canterbury pilgrimage.

So if one looks at it in this way, one sees tempered, to some extent, what seems at first to be a blatant misogynist stance by Chaucer, and one cannot help wondering if he is not perhaps showing up how extreme (and rather silly and unpractical) the anti-feminism of the Church is, by parodying their stance, (via what the husband's say) and then having the Wife reply with rhetoric that she borrows either from the Bible or from common sense.

To go along with my anti-feminist impression, there is, in addition, also the aspect of male/female violence in both the Prologue and the Tale, especially male upon female violence and the apparent suggestion in the prologue, that all women are inherently masochists, and the underlying misogynism that the latter implies.

In The Wife of Bath’s Prologue Alison introduces her fifth husband thus:

(I'm quoting a Librarius.com translation)

And now of my fifth husband will I tell.

510 God grant his soul may never get to Hell!

And yet he was to me most brutal, too;

My ribs yet feel as they were black and blue,

And ever shall, until my dying day.

But in our bed he was so fresh and gay,

515 And therewithal he could so well impose,

What time he wanted use of my belle chose,

That though he'd beaten me on every bone,

He could re-win my love, and that full soon.

I guess I loved him best of all, for he

520 Gave of his love most sparingly to me.

We women have, if I am not to lie,

In this love matter, a quaint fantasy;

Look out a thing we may not lightly have,

And after that we'll cry all day and crave.

525 Forbid a thing, and that thing covet we;

These passages seem to suggest that Alison forgave Janken for beating her, and even liked him visiting violence upon her, or at least felt excited by it, and that the violence and his withholding love from her, made her crave his love even more. I personally agree to a large extent with Hansen about these passages; that does certainly seem to be what these specific passages are saying.

The passages describing the imaginary bloody dream that Alisoun uses to draw Jankyn's attention with, to me also has disturbing sadomasochistic violent overtones, but since these passages are included in the Ellesmere manuscript, but not the Hengwrt manuscript, and there is therefore doubt that Chaucer himself wrote the passages, I will not include these passages regarding the dream in my discussion.

This theme of violence is continued in Alison's tale, in which an Arthurian knight rapes a maiden upon first sight, despite her avid protestations.

The female condonement and acceptance of this behavior is carried through in how the queen and female courtiers want the knight spared.

From The Wife of Bath’s Prologue :

"Paraventure, swich was the statut tho -

But that the queene and othere ladyes mo

So longe preyeden the kyng of grace,

Til he his lyf hym graunted in the place,

And yaf hym to the queene al at hir wille,"

So, once again, females are accepting of male violence.

However, the message in the Wife's Prologue soon becomes a contradictory one. At the end of the tale,

"But atte laste, with muchel care and wo,

We fille acorded by us selven two.

He yaf me al the bridel in myn hond,

820 To han the governance of hous and lond,

And of his tonge, and of his hond also,

And made hym brenne his book anon right tho.

And whan that I hadde geten unto me

By maistrie, al the soveraynetee,

825 And that he seyde, 'Myn owene trewe wyf,

Do as thee lust the terme of al thy lif,

Keepe thyn honour, and keep eek myn estaat,' -

After that day we hadden never debaat.

God help me so, I was to hym as kinde

830 As any wif from Denmark unto Ynde,

And also trewe, and so was he to me. "

Take note, that the Wife responds positively to the fact that this man now gave her " soveraynetee". She becomes kind to him in return, just as the old woman in the Wife's tale becomes beautiful, young and obedient, the moment that he lets her choose, that he gives her "maistrie".

This is a rather confusing message if one takes into account that the Wife's first 4 husbands did not rule her in the first place, but she treated them very badly indeed. What then would be the difference between the first 4 husbands and Jankin and the Knight?

I am able to discern three differences:

1. The first four husbands did not have the wherewithall to "rule" Alison, even if they wanted to. She ruled then in any case, by: "sleighte, or force, or by som maner thing,"

2. Both Jankin and the Knight forced dominance over women by dint of physical violence,

and

3.Both Jankin and the Knight, in the end voluntarily gave "maistrie" to their wives, and through that act, gained their wive's obedience.

The dominance aspect puzzled me at first. Why would the Wife want 'mastery' or dominance, when it would be so much better just to ask for equality?

Then I remembered that the Wife is not a real woman after all, but a "puppet" in the hands of a male, of Geoffrey Chaucer. Equality is more of a female concept while dominance is more of a male concept.

Another aspect of the theme of dominance, might also be seen in context of the kind of feudal society that Chaucer found himself in. Although the absolute power of the aristocracy was waning, monarchy was still very much the order of the day; - there was only one (secular) 'boss' (the king) in the country, and he (theoretically) had absolute power.

So perhaps part of the answer lies with the fact that from Chaucer's point of view, only one person can rule in a marriage, just as only one sovereign can rule a nation. (Never mind the fact that one might question whether it was really the temporal sovereign or the "Spiritual" sovereign (- the Pope, or Church) that ruled). Perhaps it is the very power play between Church and State of the time that Chaucer lived in that made dominance such an important thing to have. The Greeks and Romans of antiquity might have understood how to share power, but the sharing of power is not a very familiar concept in the Europe that Chaucer lived in.

On a further point, I started to find this "give over power in order to have power" concept in the message that the Wife gives, a bit less puzzling when I read the introduction to the Nevill Coghill translation of the Canterbury tales.

From the introduction by Nevill Coghill:

"It could be debated whether love could ever have a place in marriage; the typical situation in which a 'courtly lover' found himself was to be plunged in a secret, and illicit, and even an adulterous passion for some seemingly unattainable and pedestalized lady. Before his mistress a lover was prostrate, wounded to death by her beauty, killed by her disdain, obliged to an illimitable constancy, marked out for dangerous service.

A smile from her was in theory a gracious reward for twenty years of painful adoration. All Chaucer's heroes regard love when it comes upon them as the most beautiful of absolute disasters, and agony as much desired as bemoaned, ever to be pursued, never to be betrayed. ...This was not in theory the attitude of a husband to his wife. It was for a husband to command, for a wife to obey. The changes that can be rung on these antithesis are to be seen throughout the Canterbury Tales."

This is the only kind of "maistrie", of " soveraynetee" or "government" that to me personally, would make sense in the final words of the wife, when she says:

"And eek I praye Jhesu shorte hir lyves

That noght wol be governed by hir wyves."

However, I am a female, thinking with a female mind, and whether that is what Chaucer had meant the Wife's intention to be, I do not know.

I have already demonstrated at length what I find to be the antifeminist aspects of the Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale, namely the negative ways in which Alisoun portrays herself (a materialistic, power-hungry, nasty, nagging, cheating liar), and also in how readily females accept male-upon-female violence in the text of both the prologue and the tale of the Wife of Bath.

However, there are aspects of the Wife's Prologue and Tale that temper this misogyny. As I demonstrated, it is highly probable that a lot of the criticism that Alisoun and her husbands direct against women, are actually opinions expressed by the Catholic Church, who had a very strong censure against the expression of sexuality.

So to me, part of Chaucer's "pro-feminism" lies in how he seems to point out how non-sensical and unpractical many of the Church's teaching regarding sexuality, women and marriage was.

As confusing as Chaucer's point of view regarding female masochism might be for the "moral of the story", it is true, that in both the wife's prologue and in her tale, male violence is tempered, the male 'learns' not to visit violence upon women, and the females in the text do seem to rejoice in this cessation of violence.

I do not, like some feminists suggest, see the reward the knight gets at the end of the story, as being a reward for his violence. I see the reward he gets, in fact, as a reward for the cessation of violence.

Chaucer seems to encourage the code of chivalry which to me is a good thing, inasmuch as it decries violence against women.

It seems to me that here Chaucer is trying to say that males can get what they want, being 'female submissiveness and obedience' rather by dint of 'gentleness and nobility' than by force and violence, which is ignoble, and likely to cause a backlash to boot.

Even though female obedience is still the desired outcome of Chaucer's patriarchal world-view, perhaps it is infinitely better to have an obedience that is obtained through courtly love and romantic ideals, or through deference or even basic respect and gentility, than through force and violence. -

Since there has been such a spate of reviews on Goodreads recently, attending to texts that contain the depiction of female masochistic tendencies, I decided to go all the way and go way back to the first text we know of in English that contains this, being Geoffrey Chaucer's Wife of Bath's prologue and tale.

Both the tale and prologue depicts violence visited upon women, and in the prologue, it is initially even welcomed by the woman, for love of the man inflicting the violence; but just like Ana in 50 Shades of Grey, Alison decided eventually that she didn't like it, and decided to reform her attractive, sexy fifth husband Janken into more couth ways.

Arriving at a definite stance on how to interpret the message or the character of Chaucer's Wife of Bath, is not an easy task. The Wife of Bath is probably one of the characters that there seems to be least agreement upon, in the entirety of English literature, or such has been my own experience when reading scholarly interpretation upon scholarly interpretation, in order to try and clear my own confusion as to exactly what it is that the Wife herself is saying, and moreover, what Chaucer is generally saying with his creation of the Wife and her Tale.

I have come to the conclusion that the Wife of Bath is at the same time an expression of anti-feminism, and to a smaller extent of pro-feminism, each in different aspects and contexts.

I was taken aback, when I read the Wife's Prologue originally, by the apparent (to me) anti-feminism in this piece. It is quite easy to see the anti-feminist voice Chaucer is speaking with. In the Prologue to the tale, Chaucer seems to be mocking and satirizing a bossy, nagging wife - the kind of wife that most men dread and would find hard to handle.

Comments upon her from scholars seem varied; some praise her as the first feminist, though many feminists see past that and also see a male voice making a hateful parody of the female gender, and of wives in particular, but they also note and comment quite strongly upon the theme of violence weaved into this tale.

Chaucer does not paint a pretty picture of the Wife in her Prologue. She is shown as a liar and a cheat who does not hesitate to openly admit that she prostituted her body to her first four husbands for material gain, and used all manner of deceitful devices to achieve "mastery" over them.

From The Wife of Bath’s Prologue : (as translated)

"Deceit, weeping, and spinning, God doth give

To women kindly, while that they may live. *naturally

And thus of one thing I may vaunte me,

At th' end I had the better in each degree,

By sleight, or force, or by some manner thing"

(Just as a side note, it is interesting to note the use of the word "spinning" whereas Alisoun's occupation is that of a weaver.)

The latter quotation is just one example of the kind of self-revilement that goes on right through the Wife's own description of her relationships with her first four husbands, often extending the negative attributes of the Wife to the female gender in general.

To make matters worse, the wife openly admits that she did not love these four husbands, and often feigned lust just to gain more of an advantage over them.

The Wife as the product of a male construct is never more apparent than in her repeated mention of her own genitals. Over and over she mentions her own genitals (thereby objectifying the female as an object whose sole function is the sexual gratification of males) and how her husbands praised this part of her body. She also mentions how she could have sold it, (her vulva), but kept it for her husband instead (in the sense of a bargaining piece), which does seem to me to have strong overtones of suggesting that wives are little more than prostitutes.

What eyleth yow to grucche thus and grone?

Is it for ye wolde have my queynte allone?

Wy, taak it al! lo, have it every deel!

The playful tone of most of the passages in the prologue, in which the wife tends to contradict herself at times, suggests to me that they were written as entertainment largely for males, who in those times (The Canterbury Tales were thought to have been written around the 1380's) dominated the literate world.

This alone, would in my view be enough to establish a claim of this text being anti-feminist, albeit as a product, to a large extent, of the milieu that Chaucer found himself in.

However, one of the contexts in which I feel it is useful to view the Wife of Bath, is the phenomenon of Chaucer's criticism of the Catholic Church, that pervades the Canterbury tales.

From a historical background, the Black Death had not only opened the way for a stronger Bourgeoisie class, and for a stronger base in medieval society for property rights for women, (which was helped along by the fact that many males were absent/died during the Crusades) but it also weakened the grip of the Catholic Church, which was further weakened by the Western Schism, and which scenario set the stage for the Church Reformation which took place a bit later on in the course of history.

During the fourteenth century (Chaucer was born in 1343), the Catholic church was still very powerful, and many clergy abused their position of psychological power in order to gain temporal power, wealth, and it would seem, sexual/sensual gratification as well.

Chaucer seems to have been well aware of the various types of corruption that members of the Catholic institution was guilty of, from hypocrisy to avarice, to all sorts of clandestine sexual practices, which Chaucer hints at when describing the Friar, one of the Canterbury Pilgrims.

When, at the beginning of the Wife's tale, mention is made that:

"Wommen may go saufly up and doun.

In every bussh or under every tree

Ther is noon oother incubus but he, (referring to "holy" friairs)

And he ne wol doon hem but dishonour", one wonders if Chaucer is referring to the kind of sexual misconduct apparently practiced by the clergy in the 1300's- 1400's that Amanda Hopkins mentions in her article: Sex, the State and the Church in the Middle Ages: An Overview.

According to a footnote in the abovementioned article, "The evidence of medieval authors, Boccaccio and Chaucer among them, suggests that celibacy was not universally practised by the clergy.

In an examination of legal records from the Paris area in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Kathryn Gravdal finds evidence of gang rape: ‘These collective rapes seem to have been youthful sprees. Patterns in the records indicate, however, that when young clerics eventually became priests and rectors, they continued to practice sexual abuse and these constituted the second largest group of rapists brought to trial in the Cerisy court. … This finding corresponds to the figures Hanawalt and Carter have established for the clergy in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century England, where clerics constituted the largest group to stand trial for rape in the secular courts. The power and prestige of their office may have led them to commit sexual abuses with a certain regularity’

The implication of the above-mentioned research, that Chaucer might have been hinting at actual rapes being perpetrated by the clergy, seems so shocking to me, that I find it understandable that the allusion to "gang-rape by the clergy" in these passages was probably never entertained by critics like Louise O. Fradenburg, who assumes that the substitution of incubi by friars is merely a demystification, and Luarie Finke, who sees in it symbolism of changes to the economic structure of the medieval world.

The sexual activity of the clergy is especially ironic in view of the strong stance the Church officially took against the expression of any sexuality, whether hetero- or homosexual.

We jest in today's modern age about conservatives who decree that sexual intercourse is only admissible when it is vaginal heterosexual intercourse between married partners, in the missionary position, in the dark, and preferable partly clothed; but absolutely no joking: - this is exactly what the Medieval Catholic Church decreed. Any deviance from the abovementioned, was punishable by having to do "penances"; even, for instance, for the 'sin' of married heterosexual intercourse with the woman on top, or intercourse with the wife facing away from the husband.

The Pardoner who is one of the pilgrims in the Canterbury Tales, was one of the people who could gather money from the populace in order to gain pardons for such terrible crimes as, for instance, having intercourse in 'inadmissible' positions, or the even more unforgivable sin of actually enjoying it.

In view of the above and other hints throughout the rest of the Canterbury Tales, I think that a lot of what the wife says, is actually a parody of some of the negative attitudes the Catholic church held about women and marriage, and was just an additional but more subtle way in which Chaucer was criticizing the Catholicism of the day, along with his more obvious digs at the Pardoner, Summoner, Friar and Prioress who take part in the Canterbury pilgrimage.

So if one looks at it in this way, one sees tempered, to some extent, what seems at first to be a blatant anti-feminist stance by Chaucer, and one cannot help wondering if he is not perhaps showing up how extreme (and rather silly and unpractical) the antifeminism of the Church is, by parodying their stance, (via what the husband's say) and then having the Wife reply with rhetoric that she borrows either from the Bible or from common sense.

To go along with my anti-feminist impression, there is, in addition, also the aspect of male/female violence in both the Prologue and the Tale, especially male upon female violence and the apparent suggestion in the prologue, that all women are inherently masochists, and the underlying misogynism that the latter implies.

In The Wife of Bath’s Prologue Alison introduces her fifth husband thus:

(I'm quoting a Librarius.com translation)

And now of my fifth husband will I tell.

510 God grant his soul may never get to Hell!

And yet he was to me most brutal, too;

My ribs yet feel as they were black and blue,

And ever shall, until my dying day.

But in our bed he was so fresh and gay,

515 And therewithal he could so well impose,

What time he wanted use of my belle chose,

That though he'd beaten me on every bone,

He could re-win my love, and that full soon.

I guess I loved him best of all, for he

520 Gave of his love most sparingly to me.

We women have, if I am not to lie,

In this love matter, a quaint fantasy;

Look out a thing we may not lightly have,

And after that we'll cry all day and crave.

525 Forbid a thing, and that thing covet we;

These passages seem to suggest that Alison forgave Janken for beating her, and even liked him visiting violence upon her, or at least felt excited by it, and that the violence and his withholding love from her, made her crave his love even more. I personally agree to a large extent with Hansen about these passages; that does certainly seem to be what these specific passages are saying.

The passages describing the imaginary bloody dream that Alisoun uses to draw Jankyn's attention with, to me also has disturbing sadomasochistic violent overtones, but since these passages are included in the Ellesmere manuscript, but not the Hengwrt manuscript, and there is therefore doubt that Chaucer himself wrote the passages, I will not include these passages regarding the dream in my discussion.

This theme of violence is continued in Alison's tale, in which an Arthurian knight rapes a maiden upon first sight, despite her avid protestations.

The female condonement and acceptance of this behaviour is carried through in how the queen and female courtiers want the knight spared :

From The Wife of Bath’s Prologue :

"Paraventure, swich was the statut tho -

But that the queene and othere ladyes mo

So longe preyeden the kyng of grace,

Til he his lyf hym graunted in the place,

And yaf hym to the queene al at hir wille,"

So, once again, females are accepting of male violence.

However, the message in the Wife's Prologue soon becomes a contradictory one. At the end of the tale,

"But atte laste, with muchel care and wo,

We fille acorded by us selven two.

He yaf me al the bridel in myn hond,

820 To han the governance of hous and lond,

And of his tonge, and of his hond also,

And made hym brenne his book anon right tho.

And whan that I hadde geten unto me

By maistrie, al the soveraynetee,

825 And that he seyde, 'Myn owene trewe wyf,

Do as thee lust the terme of al thy lif,

Keepe thyn honour, and keep eek myn estaat,' -

After that day we hadden never debaat.

God help me so, I was to hym as kinde

830 As any wif from Denmark unto Ynde,

And also trewe, and so was he to me. "

Take note, that the Wife responds positively to the fact that this man now gave her " soveraynetee". She becomes kind to him in return, just as the old woman in the Wife's tale becomes beautiful, young and obedient, the moment that he lets her choose, that he gives her "maistrie".

This is a rather confusing message if one takes into account that the Wife's first 4 husbands did not rule her in the first place, but she treated them very badly indeed. What then would be the difference between the first 4 husbands and Jankin and the Knight?

I am able to discern three differences:

1. The first four husbands did not have the wherewithall to "rule" Alison, even if they wanted to. She ruled then in any case, by: "sleighte, or force, or by som maner thing,"

2. Both Jankin and the Knight, forced dominance over women by dint of physical violence,

and

3.Both Jankin and the Knight, in the end voluntarily gave "maistrie" to their wives, and through that act, gained their wive's obedience.

The dominance aspect puzzled me at first. Why would the Wife want 'mastery' or dominance, when it would be so much better just to ask for equality?

Then I remembered that the Wife is not a real woman after all, but a "puppet" in the hands of a male, of Geoffrey Chaucer. Equality is more of a female concept while dominance is more of a male concept.

Another aspect of the theme of dominance, might also be seen in context of the kind of feudal society that Chaucer found himself in. Although the absolute power of the aristocracy was waning, monarchy was still very much the order of the day; - there was only one (secular) 'boss'(the king) in the country, and he (theoretically) had absolute power.

So perhaps part of the answer lies with the fact that from Chaucer's point of view, only one person can rule in a marriage, just as only one sovereign can rule a nation. (Nevermind the fact that one might question whether it was really the temporal sovereign or the "Spiritual" sovereign (- the Pope, or Church) that ruled). Perhaps it is the very power play between Church and State of the time that Chaucer lived in that made dominance such an important thing to have. The Greeks and Romans of antiquity might have understood how to share power, but the sharing of power is not a very familiar concept in the Europe that Chaucer lived in.

On a further point, I started to find this "give over power in order to have power" concept in the message that the Wife gives, a bit less puzzling when I read the introduction to the Nevill Coghill translation of the Canterbury tales.

From the introduction by Nevill Coghill:

"It could be debated whether love could ever have a place in marriage; the typical situation in which a 'courtly lover' found himself was to be plunged in a secret, and illicit, and even an adulterous passion for some seemingly unattainable and pedestalized lady. Before his mistress a lover was prostrate, wounded to death by her beauty, killed by her disdain, obliged to an illimitable constancy, marked out for dangerous service.

A smile from her was in theory a gracious reward for twenty years of painful adoration. All Chaucer's heroes regard love when it comes upon them as the most beautiful of absolute disasters, and agony as much desired as bemoaned, ever to be pursued, never to be betrayed. ...This was not in theory the attitude of a husband to his wife. It was for a husband to command, for a wife to obey. The changes that can be rung on these antithesis are to be seen throughout the Canterbury Tales."

This is the only kind of "maistrie", of " soveraynetee" or "government" that to me personally, would make sense in the final words of the wife, when she says:

"And eek I praye Jhesu shorte hir lyves

That noght wol be governed by hir wyves."

However, I am a female, thinking with a female mind, and whether that is what Chaucer had meant the Wife's intention to be, I do not know.

I have already demonstrated at length what I find to be the antifeminist aspects of the Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale, namely the negative ways in which Alisoun portrays herself (a materialistic, power-hungry, nasty, nagging, cheating liar), and also in how readily females accept male-upon-female violence in the text of both the prologue and the tale of the Wife of Bath.

However, there are aspects of the Wife's Prologue and Tale that temper this ant-feminism. As I demonstrated, it is highly probable that a lot of the criticism that Alisoun and her husbands direct against women, are actually opinions expressed by the Catholic Church, who had a very strong censure against the expression of sexuality.

So to me, part of Chaucer's "pro-feminism" lies in how he seems to point out how non-sensical and unpractical many of the Church's teaching regarding sexuality, women and marriage was.

As confusing as Chaucer's point of view regarding female masochism might be for the "moral of the story", it is true, that in both the wife's prologue and in her tale, male violence is tempered, the male 'learns' not to visit violence upon women, and the females in the text do seem to rejoice in this cessation of violence.

I do not, like some feminists suggest, see the reward the knight gets at the end of the story, as being a reward for his violence. I see the reward he gets, in fact, as a reward for the cessation of violence.

Chaucer seems to encourage the code of chivalry which to me is a good thing, inasmuch as it decries violence against women.

It seems to me that here Chaucer is trying to say that males can get what they want, being "female submissiveness and obedience" rather by dint of 'gentleness and nobility' than by force and violence, which is ignoble, and likely to cause a backlash to boot.

Even though female obedience is still the desired outcome of Chaucer's patriarchal world-view, perhaps it is infinitely better to have an obedience that is obtained through courtly love and romantic ideals, or through deference or even basic respect and "gentility", than through force and violence. -

"Wedding's no sin, so far as I can learn.

Better it is to marry than to burn."

Geoffrey Chaucer, Canterbury Tales

Vol 28 of my Penguin

Little Black Classics Box Set contains both 'The Wife of Bath's Prologue' and 'The Wife of Bath's Tale' from Penguin's

The Canterbury Tales, translated by Nevill Coghill.

Personally, I preferred the Prologue to the actual Tale. The wife of Bath, or Alison, is one of the great characters from literature. I remember reading in Howard Bloom's book on Shakespeare (I think) that he believed Shakespeare 'Invented the Human' in literature. True, almost. Before Shakespeare there were few really rounded characters that could match Falstaff or Hamlet, but the Wife of Bath belongs in that literary hottub of personality. She is fantastic. Her energy, her cheek, her unabashedness about her own female sexuality and power, makes her a force and a huge influence.

I read the Canterbury Tales before in high school. But it has been awhile since I've read the 24 tales in this frame story together. I think next year I'll tackle Chaucer's masterpiece. I'm debating about reading the Coghill "translation" or the Raffel, or Peter Ackroyd's retelling. We shall see. Meanwhile, I must confess I read all of this book IN the bath. -

|| 3.0 stars ||

We were discussing

Geoffrey Chaucer for my Medieval Literature course, and

The Wife of Bath seemed like, by far, the most interesting story from

The Canterbury Tales to me. So, I figured: why not try and read it?

Well.. Upon starting this tale, I was immediately remembered as to why I do not just "try and read" things from my Medieval Literature class. In this case, the simple reason for it being: I. Do. Not. Speak. Middle. English.

So. Unless I wanted to torturously give myself the biggest headache known to mankind, trying to decipher these word-puzzles, I decided it would be best if I went and read the modern translation of this text rather than the original. So, I did.

And yea, that definitely helped. The story suddenly became readable, and I found out the content of this tale is truly quite interesting. It seems revolutionary almost in its feminism, considering it was written in the 14th century.

The prologue and tale is centred around a woman giving a random male stranger some advice about marriage, seeing how she's quite the expert after being married five times herself already.

The text gives insight into how women were treated and portrayed in the Middle Ages, yet the author also seems to use this story as a critique towards these prejudices and mistreatments towards women of his own time.

I was honestly extremely surprised by that! I didn't expect it at all, and it was kind of cool. Not going to lie.

Of course it’s not all rainbows and sunshine, though, as there are still plenty of misogynistic stereotypes to be found here. But hey. It’s written in the Middle Ages. What do you expect?

I thought this was going to be more boring, honestly, but I quite enjoyed myself while reading this. It's an interesting piece of social history. -

Now I remember why I do not like poetry, at school my poetry was considered to be good.

Why don't I like it? The teacher would say when you can write like Chaucer then you have mastered the art. Really! His writing is just cheap rhyming from 8 year olds. Whilst the story is interesting his ability is lacking, give the children a chance, there are far better poets in schools than him.

YES we were made to read this in school and we, even to this day cannot see what is special.

This man killed some childrens imaginations.

Chaucer writes by the pantameter;

I can rip the pages by the millimeter -

Dear Authors of certain books,

Before you write that book with thinly disguised rape between the two leads, I really think you should read this.

Honesty.

Thank you. -

Senin kadar çakal başka bir kadın daha tanımadım bacım ya.

-

The wife of Bath is so outrageous in her views its hilarious. there is being a feminist and then there is The Wife of Bath, she takes manipulating men to a whole other level.

-

The Wife of Bath, Alison, who has been married 5 times, justifies this scandalous behavior using knowledge gained from priests and erudite dead husbands, one of whom hit her and left her partly deaf. There's an argument for interpreting the Wife of Bath as a proto-feminist, but to me, it feels like she doesn't want to end up alone and vulnerable so she uses the phrases that most suit her cause, ignoring that most of them are sexist.

She tell the tale of a knight from King Arthur's court who rapes a maiden and, in order to save his life, must find out what women truly desire. So he goes forth and interviews a lot of women and finally finds an old hag that gives him the correct answer: all women want is dominance over their husbands. But now he's stuck with the old hag and must marry her.

What convince me that the story is not meant to make men more sympathetic to women is the ending of the tale,on the Knight's wedding night with an old hag.

Ultimately I think this story invites men to pretend that they care about their wife's judgement, nod along with it, because in the end, you're still the boss and she will follow you. I dislike this story because it pretends that a women's opinion is of some value to the medieval society. -

Read all my reviews on

http://urlphantomhive.booklikes.com

We didn't read this in class. Of course, we talked about the Canterbury Tales but actually reading it, no. That's why I was pleased to see it as a part of the Little Black Classics, giving me the opportunity to read a small part without necessary the feeling that I should read it all.

The story surprised me in a positive way. Both the Prologue and the actual Tale were far more interesting than anticipated. I'd thought it would be drier and The Wife felt rather modern (as far as I can judge in my limited knowledge of medieval woman).

Reading a story all in rhyme however, remains slightly difficult for me and it was rather distracting at times. What I didn't really like was the fact that it was a modernized translation of the text, which made it impossible to judge what the original set. It would have been nice to be able to compare the two.

Little Black Classic 28 -

Chaucer has small dick energy

-

There were times when I thought this was the medieval Chimamanda “We Should All Be Feminists” TED Talk.

Thought I only had one more uni book left but this one snuck up on me! It’s both a funny and relevant one; left me curious about more Chaucer.

Edit on Feb 13, 2023:

Changing from 5 to 4 stars on a second read (this time for the “Medieval Fanfiction” course at Harvard) because I notice now how the Wife sometimes - intentionally or not - portrays women as treacherous creatures who spin tales from the truth to benefit themselves over men. I’m not a fan of that, especially coming from a man (Chaucer). But - still appreciate the language and rhythm, and the work is overall interesting and also entertaining. -

Not an entertainer like The Miller's Tale, unless you dig chicks who manipulate men and then blame a male-dominated society. Interesting to see how long this has been happening:) Another example of how Chaucer - a celebrated polymath - understands the masses' mindset and crafts tales still debated today.

For a true medieval heroine, meet Christina of Hertfordshire :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nsA9U...

. -

it slaps xx

-

A reminder to my own self why I don’t like poetry 🥶

-

Needless to say, wonderful language and yes it was a bit entertaining sometimes, but Chaucer and I will be parting ways for a long long while.

-

I so much enjoyied and loved a marriage of Sir Gawain! <3

-

First Chaucer I have read I am ashamed to say and I was surprised to find I enjoyed this - may even encourage me to read more of the Canterbury Tales

-

Pretty good with a very simple rhyme scheme which made it quite easy to follow. Very, very outdated though. I suppose that makes it interesting from a historical perspective, but I wasn't real engaged with it at any point.

-

eh. okay

-

nothing i’ve read for class has ever pissed me off as much as this. congratulations chaucer

-

Way better than expected.

-

Meet Alison. She’s bawdy, she’s boisterous, but how anyone can describe her narrative as feminist is beyond me.

Alison’s made her way through five husbands in bewildering succession, and now considers herself a bit of an authority on the subject of matrimony. Fair enough. She’s used her sexuality - her only bartering tool - to ‘control’ her husbands. Well, all except the grand finale of Number Five who reads her religious propaganda and then strikes her so hard, he renders her partially deaf. To her fellow pilgrims, she’s very open about her sexual relations with all five husbands, and is now on the lookout for Number Six.

Is this a critique of marriage? Estate satire? A feminist commentary? No, it is a critique of the Church. Chaucer is deeply critical over the corruption of the Church, using Alison to condemn the power it holds over the illiterate as well as the conflict between bookish learning and experience as authorities to be obeyed. Of course, he does make transient references to Biblical teachings which offer little clarity when it comes to marriage: King Solomon had a thousand wives or so, so why is Alison censured for having only five husbands in comparison? But the most generous interpretation I can support is that he challenges these texts of male power to reform them, to accommodate female desire, not necessarily to defeat them.

There are allusions elsewhere that could be interpreted as feminist, but it becomes clear that it’s ultimately artifice, all feeding into the religious focus. Alison is a small industrialist: she exists outside the feudal system, making her own money and is doing rather well, truth be told. But she is submissive in more than one sense, stating boldly that her fifth and most abusive marriage was her best. What, the sex was the best? This repartee, this antithesis between anti-feminism and pro-feminism, is integral to Chaucer’s rhetoric. Shame it’s channelled elsewhere. Chaucer does not subvert the static image of women as craving sex insatiably (despite the fact the only sexual sin committed in the narrative is by the male knight), instead he reinforces it. Her ‘outrageous’ sexual comments aren’t really all that significant or progressive in context: people were open Chaucer’s day. It’s only since the Victorian era that we’ve become so prim and proper about sex. And then, women want sovereignty in a marriage, apparently. What about a strong partnership, eh?!

The resolutions are politically frustrating. Alison’s abusive husband never seems to have got his comeuppance, nor does she condemn his behaviour in any sense. The apparent sovereignty wielded by the Queen and her entourage of maids is ridiculously specious. They have been delegated the power (to decide the fate of a rapist) by a man, and their actions only reinstate the image of women as bearers of clemency. As one lad in my seminar retorted, “Yeah, but it was really good for the time…” DON’T HOMOGENISE HISTORY!!! And what makes it even worse, the knight is offered redemption. Hurrah! In fact everyone’s all hunky dory… the only character who is not offered redemption is the victim, the maiden. Fucking typical.

Besides from the infuriating presentation of women, I found Alison’s relation of her marital career rather dull aside from the occasional bawdy comment that made me snigger. Inclined to think that my exploration of The Canterbury Tales will be aborted in the light of this story. Crucify me. -

She’s the archetypal Dominatrix, and she was created over seven hundred years ago in the fourteenth century by Geoffrey Chaucer. She’s the “Wife of Bath,” and she knew a thing or two about making men behave themselves.

Usually, I look to the Greek myths, when I’m searching around for an archetype. Certainly, the myths have their share of strong women, women who really were downright superior to men. The terrifying Medusa, who could turn men, and anyone else for that matter, into stone. Athene threw her weight about a bit and Circe simply turned men into swine -- while Medea took revenge to its absolute bloody limit, by killing the kids.

The Bible too, has its share of strong women, some of them quite terrifying. Delilah, Esther, Jezebel. And the quietly strong ones, Ruth and Mary.

But as far as I can see, there is no woman before Alyson, the Wife of Bath, who made training the men in her life into an art form.

I think that Chaucer was the first writer to create characters as real people. By the end of Alyson’s tyrannical diatribe, where she challenges men in general, and God and the Bible in particular, well, we could argue with her, or cheer her on.

The Wife’s appearance is startling. In his introduction to the Wife’s prologue, James Winny tells us;

“In her brazen red stockings, her vast hat and wimple, she conforms with the standards of medieval life; noisy, assertive and robust. Her ruddy complexion, her deafness and her widely spaced teeth give her an emphatic personality such as few of the pilgrims can rival…she bursts upon the pilgrimage with the unexpectedness of a bomb, to introduce herself and a group of three connected tales.”

Alyson, the Wife of Bath, is de rigueur for the fourteenth century. These days, she would be dressed in black leather, cracking a whip and wearing killer heels. She’d probably be wearing sharply spiked spurs and have a pair of handcuffs jangling from her studded leather belt, which she wears cinched in tight at the waist.

She should have a government health warning tattooed on her wide forehead.

“Warning to men. Consort with the Wife of Bath at your own risk! -

I liked it but since the language was modernized I'd like to read some original Chaucer. I remember hating reading him in school but maybe I was just having a bad week then. I'd be curious to see if I'd like it now. This version was certainly entertaining.

-

This book (the whole Tales, not just this chapter) is much easier to read than I feared. (I’m not reading the original, I can’t. Still fun to look at the original text every now and then, and listen to some readings on YouTube.) I’m struggling with the motivation to read anything at all for the time being and was afraid I wouldn’t be able to read this either. Why on earth The Canterbury Tales seemed like a good cure to my demotivation I don’t know. I was hoping against hope, I guess. But the miracle which is these tales happened, and it’s a really good cure! I find some of the tales very funny. I like the comical ones best, like the miller’s tale and especially the ending of this one:

... May Jesus Christ send us meek husbands, young and fresh abed, and Grace to outlive the men we wed. And, also, I pray Jesus to cut short the lives of those men who will not be governed by their wives. And, to old and angry miserly husbands, may God send them soon a mortal pestilence!

Or:

And thus they lyve unto hir lyves ende

And thus they live unto their lives' end

In parfit joye; and Jhesu Crist us sende

In perfect joy; and Jesus Christ us send

Housbondes meeke, yonge, and fressh abedde,

Husbands meek, young, and vigorous in bed,

And grace t' overbyde hem that we wedde;

And grace to outlive them whom we wed;

And eek I praye Jhesu shorte hir lyves

And also I pray Jesus shorten their lives

That noght wol be governed by hir wyves;

That will not be governed by their wives;

And olde and angry nygardes of dispence,

And old and angry misers in spending,

God sende hem soone verray pestilence!

God send them soon the very pestilence!

I guess it was meant to be so preposterous it would be funny, like Lysistrata was in its time, but still, it has a bite which can’t have been only preposterous, but somehow rather clever. It’s 2020 and quite funny still. I’m impressed by the very straight talk, crude language and well-ageing humour of these stories. -

I had to read this for my studies of English and Reading Literature in University. Before then, I had never heard of Chaucer, nor The Wife of Bath’s Tale, but it wasn’t that bad of a read. I struggled to read Chaucer’s English at times but was thankful to have a modernised translation right alongside instead of attempting to decipher the word puzzles of Middle English poetry.

Admittedly, Chaucer’s Wife of Bath’s Tale was very insightful, and although I was not entirely fond of it, it was interesting to read about a woman’s perspective of society in the Middle Ages and how wrongfully treated they were.

Essentially, The Wife of Bath’s Tale Prologue is about a woman who is rightfully so angered with the church, at the men, and at the world that tells women that they cannot live a full life once they are wedded to a man, as a wife. She has made her way through five different husbands, so considers herself an authority on the subject of matrimony. She is open about her sexual relations with all different husbands, and uses that as a tool to ‘control’ them, (in other words, she’s manipulative.) Later in the Prologue, husband number five reads her religious propaganda, and then strikes her so hard that he renders her partially deaf. Her husband never seems to have gotten his comeuppance, and she does not condemn his behaviour and abusive actions, it seems to be swept under the rug. The Prologue seems to relish in the wife recounting her husband’s tales, and pays no need to the social expectations of women at the time.

Then comes The Wife of Bath’s Tale, where a knight rapes a young woman, and henceforth, the Queen punished him by telling him to go find what women want the most and to come back to her when he has found the answer. They were originally going to execute him, but apparently this instead was a suitable punishment for a rapist. Women he asks then give him differing answers, so he cannot tell the Queen a true answer. However, an old woman offers to tell him the answer—women supposedly want mastery/self sovereignty over their husbands.

And so, he gives this answer to the Queen, but the old woman interjects and states that the Knight should marry her. The Knight ends up accepting the marriage proposal due to if he had denied, he’d be seen as chivalrous in front of the Queen. So then the rest of the Tale is about how he complains the woman is too old, too ugly, and poor. The woman states that he could have her as young and beautiful, but an unfaithful wife, or an old, foul wife that will satisfy him. He says that she can choose what pleases her, and due to him giving her what she wants; mastery over her husband, she chooses to be young and beautiful, and faithful also. It ends the tale with how the wife of bath believes that husbands should bend to their will with their wives, and if not, then they should be cut short.

I can only give Chaucer two stars due to how the fate of a rapist was claimed redeemable in this tale, and the only character who is not offered redemption is the maiden, who is the victim here. There was a lot to take in while reading, and covers such critical lenses of feminism, marxism, and deconstructionism. Admittedly, both the wife, and the old woman are powerful characters of their time, but then again we also should not homogenise history. There is a lot of misogynistic stereotypes in this piece of work, and it felt quite satire.

I thought that it was going to be more boring, but I’m fortunate to have understood what The Wife of Bath’s Tale and Prologue was about. Admittedly, the Tale was easier to read than the Prologue. There’s just so much to say about this piece.