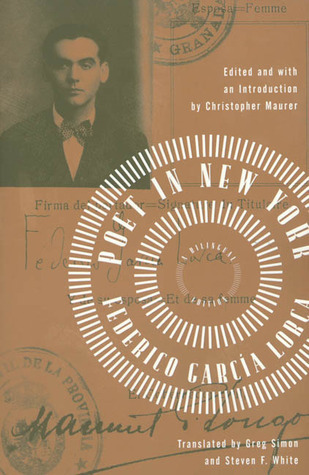

| Title | : | Poet in New York |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0374525404 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780374525408 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 352 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1940 |

In honor of the poet's centenary, the celebrated Lorca scholar Christopher Maurer has revised this strange, timeless, and vital book of verse, using much previously unavailable or untranslated material: Lorca's own manuscript of the entire book; witty and insightful letters from the poet to his family describing his feelings about America and his temporary home there (a dorm room in Columbia's John Jay Hall); the annotated photographs which accompany those letters; and a prose poem missing from previous editions. Complementing these new addtions are extensive notes and letters, revised versions of all the poems, and an interpretive lectures by Lorca himself.

An excellent introduction to the work of one of the key figures of modern poetry, this bilingual edition of Poet in New York is also a thrilling exposition of the American city in the 20th century.

Poet in New York Reviews

-

I want to cry because I feel like it

as the boys in the back row cry,

because I am not a man nor a poet nor a leaf

but a wounded pulse that probes the things of the other side.

Poetry is an odd thing. You notice this when you encounter poetry in a second language. This happened to me a few weeks ago, when I went to a poetry reading in Madrid. There were four or five poets there, some of them fairly well-known, with a crowd of hushed listeners hanging on their every word. Meanwhile, with my very imperfect Spanish, I was only able to catch bits of phrases and scattered words that added up to nothing.

“Look, I can be a poet,” I said to a friend after the show: “A cow is a moon, / a moon is a balloon.” That’s really how it sounded to me.

In a way, this isn’t surprising, of course; but it got me thinking how strange a thing is poetry. We string phrases together that, interpreted literally, are either false, absurd, meaningless, or banal; and yet somehow, when the poetry works, these phrases open up subtle emotional reactions in their listeners. Why is it that a certain phrase seems just right, inexhaustibly expressive and unutterably perfect, while a similar phrase may be dead on arrival, impotent, sterile, and maybe even unpleasant? Bad poetry, indeed, can be excruciating and embarrassing to witness, perhaps because it is in bad poetry that the essential strangeness of the act of poetry is most acutely manifest. We feel that this whole thing is silly—trying to make portentous sounding phrases that signify close to nothing. And yet the genuine article, once witnessed, is undeniable.

I usually group poetry along with novels and short stories, as literature; but lately I think that poetry may be closer to another art form: dance. Dance is distinct from every other kind of movement—from walking to golf to sign language—in that it is not oriented towards any external goal. That is, the movement itself is the goal; the point is to move, and to move well. In poetry, too, our words—which normally point us towards the world, if only to an imaginary or a hypothetical world—are stripped as much as possible of their normal denoting function; the point becomes, rather, the pure manipulation of diction and grammar, in much the same way that, in dance, the point becomes the pure movement of limb and trunk.

This is a healthy thing, I think, since in life we can get so preoccupied with the attainment of a goal that we become blind to everything that does not advance our progress towards our object. A coach of a football team, for example, is only concerned with how well his players’ actions increase the likelihood of winning; and likewise, normally when we use language, we are using it to accomplish something specific, from ordering pizza to chiding children. Dance and poetry, by stripping away the intentionality of the act, reveal the subtle beauty in the activity itself, allowing us to slow down, to appreciate the rhythm of a word or the gentle flexion of an arm.

I must hasten to add that this description of poetry and dance does not apply equally to all examples. Alexander Pope’s poetry approaches very nearly to prose in its use of denotation; and T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” is on the other side of the spectrum. A similar spectrum applies in the case of dance, I suppose.

Federico García Lorca’s poetry is much closer to Eliot’s in this regard, perhaps even further along in its tendency towards connotation. This makes his poetry doubly hard for a foreigner like me to appreciate, since the specific emotional flavors of his words are bland in my mouth. As a young man Lorca lived in the famous Residencia de Estudiantes, in Madrid, where he became close friends with Dalí. The two exerted a mutual influence on each other, both moving towards the surrealism that was becoming trendy in the art world.

Lorca wrote this book many years later, during and after his visit to New York City in 1929-30, during which he witnessed the Stock Market Crash. Economic depression or not, however, the inhuman vastness of the city, the crowds and concrete, the money-obsessed workers and the poor and the homeless, the racial discrimination and the absence of nature, seems to have made a deep impression on the rural Andalusian poet. These poems are his anguished response to this experience.

Lorca’s poetry is surreal in the textbook sense that he uses a succession of vivid, concrete images that, taken together, add up to something nebulous and unreal. Much like Dalí, Lorca has a talent for creating bizarre images that nevertheless manage to be emotionally compelling. Opening the collection more or less at random I find:All is broken in the night,

its legs spread wide over the terraces.

All is broken in the warm pipes

of a terrible, silent fountain.

Admittedly it does take some time to find the odd beauty in the apparently random, unconnected pictures. My first instinct was to read them like metaphors; but if Lorca did indeed have something specific in mind that he was trying to allegorize, the allegories are much too complicated and disjointed to be deciphered. Rather, I think these poems must be read simply for the beauty of the language, the striking collisions of words, the flashes of light and the rumblings of sound. The poems seem to capture nothing more nor less than an emotional mood—different shades of desolation—that presents itself to the conscious mind in a kind of personal mythology, as in a dream. Dalí was deeply influenced by Freud during his stay in the student residence, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Lorca was too.

Even if it is difficult to articulate the structure and meaning of Lorca’s image-world, it is certainly not random. Certain words and images come up again and again, as in a dream sequence, being shuffled and re-shuffled throughout the collection. Some of these words are oil, ant, worm, thigh, moon, void, footprint, hollow, glass, night, wounded, agony, sky, cracked, death, coffin, iron… The ultimate effect of these words, recombined again and again, is cumulative; they create echoes of themselves in the reader’s mind, calling up half-remembered associations from other poems, creating an emotional coherence in the literally incoherent text.Look at concrete shapes seeking their void.

Mistaken dogs and bitten apples.

Look at the longing, the anguish of a sad fossil world

that cannot find the accent of its first sob.

The emotional resonance of the words themselves is also important, something that is unfortunately lost in translation. For example, the word for “oil,” aceite, has an interesting blend of comforting familiarity and a tint of the exotic. I think this is because the word originally comes from Arabic, and maintains a certain foreign flavor, even as it denotes something absolutely integral to the Spanish culture: olive oil, which is used in everything. The word also brings up the rolling olive fields, stumpy trees on sandy soil, that fill Lorca's Andalucía; and this again calls to mind the age-old farming tradition, the intimate connection with the land, totally absent in New York City. There is also the double association of oil as integral to cooking and as something potentially toxic and polluting. A native Spaniard will likely disagree with this chain of associations, but I think the word is undeniably resonant.

Ultimately, though, I don’t think I can articulate exactly why the text of these poems is gripping, in the same way that I cannot articulate exactly why I find some dancers compelling and others not. You cannot learn anything about New York City from these poems, and arguably you can’t learn very much about Lorca, either. I’m not even sure that the cliché is correct, that these poems can "teach you about yourself." Maybe they don't teach anything except how to feel as Lorca felt. I don’t think that’s a problem, though, since the point of reading is not always to learn about something, just as the point of moving isn’t always to get somewhere. Sometimes we read simply for the pleasure of the text. -

A collection of haunting poems about life in New York, New England, and, to a lesser extent, Cuba. Compared to the classical starkness of Romancero gitano the poetry here's more obscure, full of opaque symbols and enigmatic language. Each piece, while still short, feels dense; taken together the poems paint a dark portrait of urban and rural life in the Northeast, marked by hard labor, longing, and regret.

-

Devastating poems composed during the Andalusian bard’s 1929-30 stay in New York. This edition contains a brilliant introduction and unobtrusive commentaries, plus a lecture (which I read) and letters to his family (which I skipped). My favourite of the cycle is this spinechilling number from Part III, Streets and Dreams (with incorrect line breaks and my apologies to the poet):

Sleepless City (Brooklyn Bridge Nocturne)

Out in the sky, no one sleeps. No one, no one.

No one sleeps.

Lunar creatures sniff and circle the dwellings.

Live iguanas will come to bite the men who don’t dream,

and the brokenhearted fugitive will meet on street corners

an incredible crocodile resting beneath the tender protest of the

stars.

Out in the world, no one sleeps. No one, no one.

No one sleeps.

There is a corpse in the farthest graveyard

complaining for three years

because of an arid landscape in his knee;

and a boy who was buried this morning cried so much

they had to call the dogs to quiet him.

Life is no dream. Watch out! Watch out! Watch out!

We fall down stairs and eat the moist earth,

or we climb to the snow’s edge with the choir of dead dahlias.

But there is no oblivion, no dream:

raw flesh. Kisses tie mouths

in a tangle of new veins

and those who are hurt will hurt without rest

and those who are frightened by death will carry it on their

shoulders.

One day

horses will live in the taverns

and furious ants

will attack the yellow skies that take refuge in the eyes of cattle.

Another day

we’ll witness the resurrection of dead butterflies,

and still walking in a landscape of gray sponges and silent ships,

we’ll see our ring shine and rose spill from our tongues.

Watch out! Watch out! Watch out!

Those still marked by claws and cloudburst,

that boy who cries because he doesn’t know about the invention

of bridges,

or that corpse that has nothing more than its head and

one shoe—

they all must be led to the wall where iguanas and serpents wait,

where the bear’s teeth wait,

where the mummified hand of a child waits

and the camel’s fur bristles with a violent blue chill.

Out in the sky, no one sleeps. No one, no one.

No one sleeps.

But if someone closes his eyes,

whip him, my children, whip him!

Let there be a panorama of open eyes

and bitter inflamed wounds.

Out in the world, no one sleeps. No one. No one.

I’ve said it before.

No one sleeps.

But at night, if someone has too much moss on his temples,

open the trap doors so he can see in moonlight

the fake goblets, the venom, and the skull of the theaters. -

Me ha impactado ,lo he leído poco a poco porque captó de tal manera el sufrimiento y la angustia que aveces me costaba continuar la lectura.

💙Lorca era un genio y sorprende como de una breve estancia en la Universidad de Columbia fue capaz de captar los matices del día a día de la vida gris y del sufrimiento de las minorías étnicas y sociales.

🌓Leerlo es como ver un cuadro de Dalí hecho palabra:insectos,sangre,muerte...

📌”Cuando la luna salga

las poleas rodarán para tumbar el cielo;

un límite de agujas cercará la memoria

y los ataúdes se llevarán a los que no trabajan.

Nueva York de cieno,

Nueva York de alambres y muerte.”

📚Magistralmente estructurado. -

De Lorca no hay que hablar, hay que leer, leer, leer...

-

The architectures of frost,

the lyres and moans that escape the tiny leaves

in autumn, soaking the final slopes,

died out in the blackness of felt hats.

Not wishing to exaggerate, I found this to be wonderful and perhaps my favorite book of verse in some time. Lorca, conversely, was prone to hyperbole or simple fantasy especially in his marvelous letters home from his North American endeavor.

His depiction of African-Americans might strike some as jarring. Such is foregrounded in both the poetry and the correspondence. It is interesting to consider how De Beauvoir in her letters to Sartre used similar language of wonder to describe such. FGL's Catholicism is also a penumbra, especially regarding Protestantism and his sojourns along Wall Street.

When you look more closely at the mechanism of social life and the painful slavery of both men and machines, you see that it is nothing but a kind of typical empty anguish that makes even crime and gangs forgivable means of escape.

The poet's arrogance is striking but forgivable. He claims everyone loves him. The annotations suggest otherwise. Everyone clamors for him to sing and to recite his verse. He comments on the cost of everything and notices minute conveniences which stir his amazement. He also recognizes the perils of the mass city and the unfortunate wage-earners who maintain its breakneck velocity. FGL deftly channels the Das Man of Heidegger. His sociological asides are interesting, especially when considering those of Stephen Spender who went to Spain a few years later: both appear intrigued and sometimes shaken by strange customs. -

Guess he didn't like New York.

-

"On this bridge, Lorca warns, life is not a dream. Beware, and beware, and beware.... Before you drift off, don't forget, which is to say, remember—because remembering is so much more a psychotic activity than forgetting—Lorca in that same poem said that the iguana will bite those who do not dream."

These lines, spoken by Timothy "Speed" Levitch as he stands on the Brooklyn Bridge in my favorite movie, Waking Life, always intrigued me. The idea of the Spanish poet Lorca on the Brooklyn Bridge was hard for me to imagine, seemed implausible somehow, but eventually I realized this was only because I saw the bridge as such contemporary symbol. In reality, it opened for business in 1883, in plenty of time for Lorca to visit. But what was Lorca doing there? I always wondered, and when I realized he had published a collection called Poet in New York, I figured that would have the answer. And it did!

Lorca made an extended visit to Manhattan from Spain on a fellowship to Columbia University. He arrived in late 1929, and if you know anything about U.S. history, you know that was likely an insane time to visit New York City. On top of that, Lorca had his own problems: A devout Catholic, he was wrestling with his homosexuality and the fact that it put him in opposition to his beloved church.

The resulting poems are dark, full of nightmarish images—haunting, vivid depictions of suffering people and predatory beasts. Unfortunately, as interesting as I found the story behind the poems, I was less taken with the poems themselves. I enjoyed an homage to Walt Whitman and recognized some of the Catholic imagery, but I was in the dark about a lot of the other symbols employed—and in fact, I doubted that many of the images actually symbolized anything; they seemed instead random, and after a certain point, ineffective. I thought a section dedicated to a trip to the New England countryside might provide some relief and some variety, but most of those poems were just as unrelentingly dark as the others. I also had some doubts about the translation: My edition features side-by-side Spanish and English, which I appreciated, but often when I wondered about the use of a particular English word or phrase and consulted the Spanish, I was left unsatisfied and confused about the choices the translators made. Granted, my Spanish is not the best, but, whether justified or not, my doubts didn't improve my experience of the book.

I wouldn't discourage anyone from reading Poet in New York—there is most definitely a lot that's interesting here. But this collection isn't really for a casual reader (and yes, in this instance I definitely consider myself a casual reader!). I think thoroughly understanding this book would require more time and effort than I'm willing to put into it at present. Maybe someday. -

Uno de mis grandes pendientes y, aunque no es mi favorito de Lorca (porque esa es una lucha reñida), he disfrutado mucho leyéndolo y, sobre todo, leyendo entre líneas.

-

To see that everything has gone,

love unassailable, fleeting love!

No, don't give me your hole

now that mine goes through the air!

Ay de ti, ay de mi, pity the breeze!

To see that everything has gone. -

Hay quien dice que el público adoraba Romancero Gitano porque lo entendía. Éste no se entendió. Yo debo de ser una de esas personas.

Publicado póstumamente en 1940. -

"Yeni bir yüzyıl ya da yeni bir ışık yok / Sadece mavi bir at ve bir şafak var."

Franco diktatörlüğünün sayısız kurbanından biri olan, daha 38 yaşındayken kurşuna dizilen ve bugüne dek kemikleri bile bulunamamış büyük şair Federico Garcia Lorca'nın 30'lu yaşlarının başında New York'tayken yazdığı şiirlerden bir seçki "New York'ta Bir Şair".

Lorca'ya sevgim Leonard Cohen'den ötürü. Ne diyordu Lawrence Durrell; "İnsan aşık olduğu kişinin aşık olmayı seçtiği kişiye de aşık olur" - işte tam öyle. Leonard Cohen, kızının adını Lorca koyacak denli bir büyük Lorca hayranı, o sevince ben de sevmiş oluyorum zaten. (Olamaz mı?) Neyse, Cohen demişken; kendisinin "Take This Waltz" şarkısının sözlerini uyarladığı Lorca şiiri "Küçük Bir Viyana Valsi" de var bu kitabın içinde.

Ben şiir çok severim ama çeviri şiirde de bir o kadar zorlanırım, yine aynı şey oldu. Açıkçası şiir çevirisi öyle netameli bir iş ki; çeviriye iyi veya kötü bile diyemiyorum, anlamak çok güç çünkü. Ama sevdim mi, sevdim; fakat "şunları İspanyolca'dan okusam hazdan aklımı kaçırırdım herhalde" hissi de kitap boyunca peşimi bırakmadı.

Epey hüzünlü, çok görkemli, pek latif şiirler bunlar. Ne diyeyim, umarım bir gün kendi dillerinden de okuma şansım olur. Şöyle bitsin: "Göğsünde kağıttan bir kuş / Henüz öpüşme zamanının gelmediğini söylüyor." ❤️ -

Realmente amé la lectura de este libro porque puedes sentir toda la tristeza, enojo y asco que siente el autor. Simplemente no podemos ignorar todas las cosas que dice sobre la sociedad, cómo todos vamos tan rápido que no nos importa nada ni nadie, o cómo la injusticia y la desigualdad son las estrellas de nuestros días.

No recomendaría la obra de Lorca a nadie que se acerque a la poesía, principalmente porque es rica en simbolismo y puede ser difícil captar el significado final del poema. Sin embargo, Lorca tiene una manera bastante singular de describir (en este caso) los alrededores de una ciudad y una forma de vida que es totalmente nueva para él. Perspicaz y astuto, muestra sus puntos de vista sobre una variedad de temas como el capitalismo, la soledad, el amor perdido y el respeto entre otros.

Entre sus páginas puedes notar todo el corazón, emoción, desesperación y anhelo de Lorca para transmitir la cruda desolación de Nueva York. Con este poemario dejó al mundo un tesoro literario. -

Imprescindible. No sólo por ser Lorca, por ser un gran nombre de nuestras letras. Imprescindible por sí mismo. Una gran lectura.

http://entremontonesdelibros.blogspot... -

I knew nothing of Lorca until this weekend, which saddens and embarrasses me since I adore Spanish culture. I watched the film 'Little Ashes' thinking it was about Salvador Dali but found the life and causes of Dali's poet lover Federico Garcia Lorca much more compelling. My friend was kind enough to lend me this book of poems he wrote about his experiences while studying in New York and visiting Cuba.

This edition came with a fantastic introduction which gave a lot of context to the often confusing maze of personal references and symbols in these poems. Appendices included a lecture about New York by Lorca alongside letters to his family, which also helped the reader understand Lorca's approach to his alien urban landscape.

The poems are presented in both Spanish and English, side by side. Though my Spanish is sketchy (I could only translate about 30% of each poem at best)it was fantastic being able to see the poems in their original language and being able to work out the original meter and words which are near impossible to translate into English (a common word is 'Huecos' - an empty, indefinite space).

I've written so much about the advantages of this edition because all of this led to me loving the collection. They cover the common themes of alienation in a crowded place, social revolution and lost childhood with the imaginative approach which defined Spanish art in the 20's and 30's. Critics often call him a 'surreal' poet, but the seemingly random symbols of the horse, frog, elephant, dove and crocodile are repeated endlessly, creating a running thread through the collection which grounds them against the fanciful flight of surrealism.

Lorca doesn't take the obvious route of describing skyscrapers and sniping the greed of Wall Street (though he does mention witnessing the Wall Street crash first hand in his lecture), but instead extracts an essence of urbanity which is best seen in 'Blind Panorama of New York', where the pollution of the city is conveyed as birds covered in ash and its banalities are caterpillars in the mind which 'devour the philosopher'. His landscapes of the 'Vomiting Multitude' at Coney Island and the 'Sleepless City' by Brookyln Bridge paint a grim picture which is still laced with love and wonderment.

I did find it hard to get any meaning out of some of these poems (particularly the ones about Lorca's friendships and relationships, full of in-jokes and nonsense), but they still remained beautiful and a pleasure to read.

One of the best collections of poetry I have ever read, I now want to improve my Spanish so I can better understand and appreciate it. -

Poet, prozator şi dramaturg spaniol foarte cunoscut, Federico Garcia Lorca s-a născut în 1898 în regiunea Granada, iar la doar 38 de ani a fost ucis în timpul Războiului Civil din Spania (1936-1939). După o experienţă de vizitare a New York-ului, în urma căreia am citit că nu a reuşit să înveţe limba engleză, a rămas cu o impresie mai degrabă neplăcută şi o imagine sumbră a metropolei, totul concretizat apoi în versurile încărcate de simboluri şi metafore din volumul de faţă, apărut la noi în 2020 în traducerea lui Marin Mălaicu-Hondrari.

Recenzia integrală:

https://ancazaharia.ro/2020/09/cerul-... -

o Lorca. If only you were buried nearby so I could hump your grave while sobbing. Best, most tortured, sweetest, strangest, most bitter.

-

Federico García Lorca (1898-1936) a fost cel mai important poet spaniel din secolul XX, executat în 1936 de extremiștii de dreapta sub conducerea generalului Franco. A fost ucis nu doar pentru direcțiile lui politice, dar și pentru că era gay declarat.

Deși l-am găsit menționat în mai multe articole atât pentru cât de iubit și admirat a fost ca artist, cât și pentru moartea nedreaptă pe care a avut-o la doar 38 de ani, Poetul la New York, „Poeta en Nueva York” este primul volum scris de el pe care îl citesc.

Tradus în română de Marin Mălaicu-Hondrari (ceea ce m-a și încurajat să îl comand), volumul este un jurnal de-a dreptul sfâșietor a celor 9 luni petrecute de Federico García Lorca la Columbia University. Sunt emoții pe alocuri zdrobitoare, sunt versuri senzoriale, singurătăți goale, singurătăți pline. Rasism, tulburări sociale, afecțiuni fizice și emoționale, sărăcie - un peisaj pe care îl regăseam în metropola americană de după căderea bursei.

Pe lângă traducerea impecabilă pe care o puteam anticipa, am rămas cu vreo 4 ilustrații pe retina – cartea este ilustrată de pictorul și ilustratorul spaniol Fernando Vicente. O treabă excepțională a făcut! Ilustrațiile sunt abrupte, dure și sensibile, exact ca poezia din volum.

MY FAV QUOTES:

Nu mă întrebați nimic. Am văzut cum lucrurile

Când își caută matca își întâlnesc propriul vid.

Există o durere a golurilor în aerul nelocuit

și în ochii mei ființe în haine – nedezbrăcate!

**

Bețivii se înfruptă din moarte.

**

Marea și-a amintit – dintr-odată! –

numele tuturor înecaților săi.

**

Lumea caută farmaciile

unde înțepenește tropicul amar.

**

E fără rost să cauți cotitura

unde noaptea își uită drumul

și să pândești o liniște lipsită de

haine rupte, scoarță și plânset,

pentru că și ospățul pipernict al păianjenului

poate rupe echilibrul fiecărui cer.

**

Habar nu aveam că gândul are suburbii.

**

N-o să pot plânge

dacă nu voi găsi ce căutam;

dar am să mă duc în primul loc plin de umezează și clocotitor

pentru a înțelege că ceea ce caut va avea drept țel bucuria

când voi zbura la un loc cu iubirea și nisipurile.

**

... vorbea cu cochiliile goale ale documentelor.

**

Chinul meu sângera după-amiaza

când ochii tăi erau ziduri,

când mâinile tale erau două țări,

iar trupul meu freamăt de iarbă.

**

În tine, dragostea mea, în camera ta

câte brațe de mumie înflorită!

cât cer fără ieșire, dragostea mea, cât cer!

**

Dar tu cutreieri bezmetic prin ochii mei oftând.

**

Nu, nu-mi da golul tău,

căci vine-al meu în zbor la tine!

**

O să tot paștem fără odihnă iarba cimitirelor. -

Toni cupi, di morte e solitudine, che nulla hanno a che fare con il Lorca vitale de Libro de Poemas.

E' una New York grottesca, sordida e alienata. Le metafore e le sinestesie si intrecciano così vorticosamente da lasciare sempre meno spazio alla comprensione del lettore. Si sa, la poesia parla per archetipi e forse è proprio questo ciò che ci fa amarla: non doverla sottoporre al microscopio della ragione, eppure stavolta avrei preferito qualche verso meno criptico.

Ode a Walt Whitman è commovente. -

A favourite book, which I've had since my youth, when I was discovering a wider world.

-

En otros tiempos,

habría dicho que el verso

‘y hay barcos que buscan ser mirados para poder

hundirse tranquilos’

me había salvado la vida. -

How to write a review of a work that I barely understand, but find so beautiful I have to give it 5 bright, and shining stars?

I bought my first copy of Poet in New York over 40 years ago. It was Ben Bellit's translation. Mr. Bellit has also translated Pablo Neruda. I can't say as I find any of his translations readable. But, I persevered, opening the book every now and then, and finding the lines mostly incomprehensible blamed the translation and said, "Maybe later."

The new Simon and White translation came out in 1988, and got a lot of praise, so, I filed it away in my mind, and finally bought it used last year. (I found it at Vargo's Books, an eccectric and popular bookstore in Bozeman, Montana.) It sat on the shelf, until its time finally came.

I'm here to report Poet in New York remains mostly incomprehensible, though the translation seems to flow much more easily than the Bellit. I want to add the caveat that there are people who can read Poet in New York more deeply than I, and come up with terrific ideas about what Garcia Lorca is doing - I thank them for the efforts though it wasn't until I read what the poet said he was trying to do that I got any closer to understanding. For that, see below.

When I finally read William Burrough's, Naked Lunch, (yes, I'm one of the few and the brave who actually read the whole damn, incomprehensible ((there's that word again)) thing )I told myself that I could easily press on to just about anything.

I have come to learn there's the bizarrely incomprehensible (Naked Lunch,) and the extraordinarily beautiful incomprehensible - Poet in New York.

Poet in New York tracks Garcia Lorca's first visit to a foreign country, and, according to the poet, is his conscious leap into a world of images that he pushes beyond surrealism. He's trying to create poems as things that stand alone in space and time. He's not manipulating the world to get at something deeper, he's summoning from the depths. I get it, and I get that what I have to do is read, without expectations, as if I were listening to - what? - not the Oracle at Delphi because I'd be parsing a prophecy there, but maybe to a mind-traveller from another planet. Ok, there's pleasure to be found there, and the pleasure I find with Poet in New York is in lines and stanzas that stand outside of whole poems and shimmer. (Am I making any sense?)

In "Double Poem of Lake Eden," I find this:

I want to cry because I feel like it -

the way children cry in the last row of seats...

(My note: that struck me not only as an emotional jolt, but a perfect image I could place in a dark theater, or bright classroom.)

because I'm not a man, not a poet, not a leaf,

only a wounded pulse that circles the things of the other side.

(My note: The poet reduced to a "wounded pulse" resonates at a pretty deep level, and the idea of a spirit "circling the things of the other side," certainly lifts my head off. And that's the truth of Lorca - his work is the essence of Dickenson's recognition of poetry.)

Or here's a line from Dance of Death: The dead are engrossed in devouring their own hands.

Or this, from Little Stanton: In the house where there is cancer,/ the white walls shatter in the delirium of astronomy. (My note: This is about a child diagnosed with cancer, so of course "the white walls shatter..." And the "delirium of astronomy," comes at me like galaxies blown apart and scattered by the grief of it all. Now, I'm just making stuff up here, so...)

I could go on. Almost every poem in the collection contains lines mysterious and head-lifting. Garcia Lorca is the poet of the deep song, canto hondo, and duende - knowledge and action in the presence of death.

The final section (X) is called The Poet Arrives in Havana. It's comprised of one poem, Blacks Dancing to Cuban Rhythms, and it starts:

As soon as the full moon rises, I'm going to Santiago, Cuba/I'm going to Santiago...

The poet and the poem are ecstatic at leaving New York. So was I.

I will, of course, be revisiting Poet in New York, for now, I'm thrilled to have finally read it. -

This is a fantastic book. I hear the word "Surrealism" tossed around a lot in reference to this work, but I'm not sure that I agree with that description, even though I understand what people mean when they say it. In my opinion, Lorca is attempting to use words in a descriptive way so as to capture setting, emotion and character, (many times the setting and character are New York, the city itself)much in the way an artist uses paint.The words themselves transcend their literal meanings. What astounds is the sheer ease and grace that seems to pour from Garcia-Lorca's mind directly into words. This is a gifted Poet. Nothing in these poems ever sounds forced and he doesn't seem to repeat himself, (except in conceptual tone, which is understandable, and probably intentional, in writing in and about his experiences in N.Y.)Having the Spanish and the English translation on same-facing pages is a great device, too. I appreciate being able to read both concurrently. (I don't read Spanish, but I can compare the versions and see which words are translated into English and I find this helpful and interesting.)Overall, I find this book to be an amazing emotional portrait of a city and its inhabitants by one of the most singular visionary Poets in history. Invaluable.

-

"Cuando se hundieron las formas puras

Bajo el cri cri de las margaritas, comprendí que me habían asesinado.

Recorrieron los cafés y los cementerios y las iglesias.

Abrieron los toneles y los armarios.

Destrozaron tres esqueletos para arrancar sus dientes de oro.

Ya no me encuentraron.

¿No me encontraron?

No. No me encuentraron."

Si lo piensas este poema es muy triste, ya que 8 años después a el y a tres personas mas las asesinaron y no se encontraron sus cadáveres. :c -

Poco que decir de esta obra maestra de la poesía española, sino que la releo a menudo. La profundidad temática, pero, sobre todo, el ritmo de todos y cada uno de los poemas que componen este poemario es impresionante. La técnica magistral. En fin, se nota claramente que Lorca es mi poeta favorito, así que no puedo dejar de recomendar su lectura.

-

"I want to cry because I feel like it—

the way children cry in the last row

of seats—

because I’m not a man, not a poet,

not a leaf,

only a wounded pulse that probes

the

things of the other side." -

No me he enterado de nada pero magustao.

-

Un poemario increíble, García Lorca fue un hombre adelantado a su tiempo y eso se puede leer en numerosos versos. El poemario es muy breve y ameno, perfecto para leer en una tarde.

-

Un libro ideal para un fin de semana lluvioso. Como todos los libros de Lorca, este es un viaje por imágenes, sensaciones, tiempos y palabras conocidos y desconocidos. Es un libro complejo, de varias lecturas y muchas perspectivas. Eres grande, Lorca.

-

Gabriel Garcia Lorca truly shows that when it comes to the movements as a city with ties to industry, capitalistic gain and material wealth, there is no division between the life of the human being and the life of the machine. Lorca arrived in New York just in time to witness the chaos created by the 1929 stock market crash. The poet's favorite neighborhood was Harlem; he loved African-American spirituals, which reminded him of Spain's "deep songs."

Like jazz and soul, it holds rage, irony and grief in uneasy equilibrium and relies heavily on a razor-sharp rhythmic and tonal sense to convey its meanings.

Lorca sought out New York, and the city returned the favor by hyper-stimulating him. In September, describing the city in a letter to Melchor Fernandez Almagro, he said, “It’s immense, but it is made for man, the human proportion adjusts to things that from far away seem gigantic and disordered.”

Another lure of New York was that from there Lorca could travel to Cuba, which he had dreamed of visiting since his childhood. Whereas Lorca probably would not have gotten his parents to fund a trip to Cuba directly, he could travel to the island from New York, where he had the legitimate excuse of studying English at a prestigious American university.

I believe that Lorca's observations and journal entries are a reflection of not only the mindset of one of the most well known cities in the world, applicable to the 1930s, but is also quite accurately a reflection of the state of the world today.