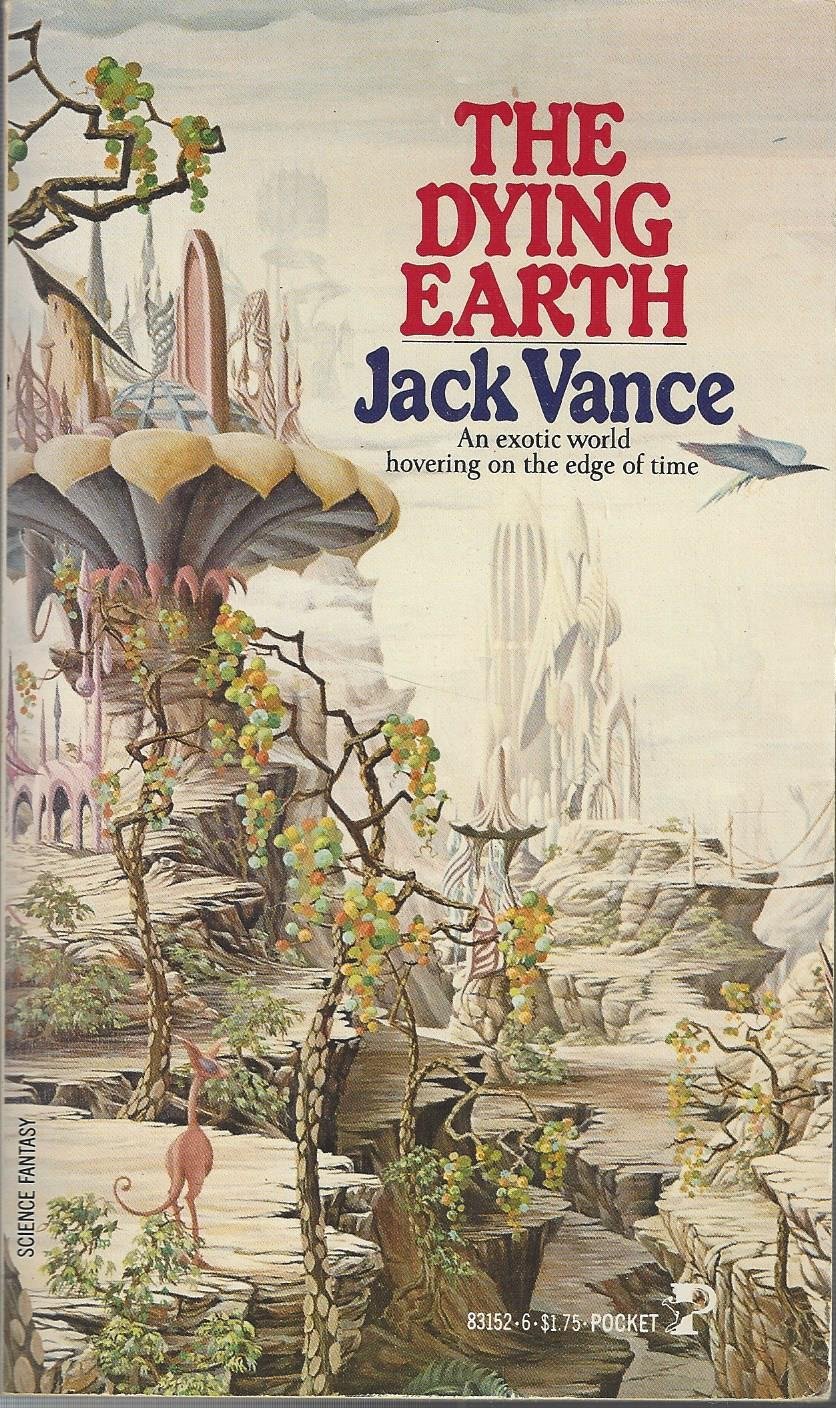

| Title | : | The Dying Earth (The Dying Earth, #1) |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0671831526 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780671831523 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 156 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1950 |

| Awards | : | Retro Hugo Award Best Novel (2001) |

The Dying Earth (The Dying Earth, #1) Reviews

-

I did not like this book much the first time I read it, but after reading it a second time while visualizing its characters as puppets, I found I liked it much more.

This book—particularly the first three stories—irritated me. I found its wizards to be contemptible creatures, morally inferior products of a degenerate age, capable only of memorizing a few detailed spells and casting them by rote (“Vancian Magic,” which later became a key element of “Dungeons and Dragons”). I was also appalled by their sexism: even the best try to fashion ideal women from scratch, while the majority desire only to catch women, cage them and rape them—the real reason for all their pathetic little spells. In addition, the book's prose—particularly the wizards' speeches—is grandiloquent and eccentric, harsh and grating, and crammed full of hard words. Such words—I remember thinking to myself—remind me of what Shakespeare's Angus says of Macbeth's titles: they “hang loose about him, like a giant's robe/ Upon a dwarfish thief.”

This Renaissance reference must have unearthed old memories, for soon I was transported back to grad school at Ohio State, some forty years ago. At the time I was studying John Marston, and I was having a good deal of trouble enjoying his tragedies (Antonio and Mellida, Antonio's Revenge) because the speeches were so pompous, so ridiculously passionate, the plots so elaborate and absurd. Then I discovered a fact that changed my reaction completely. Whereas Shakespeare wrote for a general audience at an open air theater featuring adult actors, Marston wrote for an elite audience in a candlelit indoor theater featuring an acting company of children. Each of these passionate, pompous speeches—filled with mammoth emotions and murderous intent—had been declaimed in chiaroscuro by a costumed child. Knowing this, I could now appreciate Marston's mix of humor and biting satire. He was using grand speeches in the mouths of children to show us the littleness of man, a poor paltry creature of monumental passions trapped in a flickering world.

So I read The Dying Earth again, as if it were a Punch and Judy show mounted with magnificent sets. Puppet wizards and puppet women now moved through a muted landscape, in a world of distilled evil dominated by a decadent sun. Sometimes they seem like mischievous children, sometimes like degenerate dwarfs, but at other times they seem like creatures of some new myth, a promise of stories to come beyond this dying world.

So my advice is: stick with it. Imagine the characters as puppets or children or mice if you have to, but read this book all the way through until you get to the end. These stories—which are among Vance's first—get better as they go along, and the last three are very good indeed. The most interesting, at least as a literary influence, is “Ulan Dhor Ends a Dream.” This account of a metropolis where two different peoples live side by side, completely unable to perceive each others existence, bears striking similarities to China Mieville's The City and the City,. My favorite is “Liane the Wayfarer,” about a quest for a tapestry possessed by “Chun the Unavoidable,” but equally as good is the novella about the inquisitive “Guyal of Sfere,” who has many questions to ask the Curator of “The Museum of Man.” -

There is some strange depressing morbid fascination in imagining the world - our Earth - an uncountable number of millennia in the future as an unrecognizably changed tired, dying ancient world orbiting the tired, dying ancient red Sun. It's the world in its last breaths, with the knowledge that eventually the life will stop with the Sun.

"Soon, when the sun goes out, men will stare into the eternal night, and all will die, and Earth will bear its history, its ruins, the mountains worn to knolls – all into the infinite dark."

Jack Vance's The Dying Earth is made of six short stories, somewhat interconnected, all set on future ancient Earth under the light of the dying Sun. It's a sad world, with the inhabitants reduced to a tiny fraction of the former populations, with science lost and replaced by magic (albeit somehow, in the far past, rooted in the ancient lore of mathematics), with hints of the former civilizations (none of them ours) hidden in the ancient ruins, with people squabbling over spells and knowledge and survival. It's a bleak yet fascinating universe.“Earth," mused Pandelume. "A dim place, ancient beyond knowledge. Once it was a tall world of cloudy mountains and bright rivers, and the sun was a white blazing ball. Ages of rain and wind have beaten and rounded the granite, and the sun is feeble and red. The continents have sunk and risen. A million cities have lifted towers, have fallen to dust. In place of the old peoples a few thousand strange souls live. There is evil on Earth, evil distilled by time... Earth is dying and in its twilight...”

Written in the 1940s and published as a collection in 1950, these stories apparently became an inspiration to quite a bit of the modern fantasy. It's easy to see why - despite overall not being heavy on traditional plot, the stories are captivating mostly through the intricately created world of Vance's stories, with beautifully crafted atmosphere, with vivid and a bit baroque descriptions. It's overall dark and yet darkly enchanting, a world where there's no clear good or evil but rather people just scrapping to see another day.

In the end, however, there is a glimpse of hope - hope that comes not through cunning sorcery but through knowledge, giving this fantasy story a path into the land of science fiction, giving a he of something new to the world of old.Guyal, leaning back on the weathered pillar, looked up to the stars. "Knowledge is ours, Shierl - all of knowing to our call. And what shall we do?"

Together they looked up to the white stars.

"What shall we do..."

3.5 stars.

——————

Also posted on

my blog. -

Jack Vance’s genre defining, fundamentally influential 1950 fantasy novel about swords, sorcery and ancient technology while the red glow of a dying sun spins over a far future earth is a SF/F gem.

A collection of related short stories, Vance’s mastery of the language and his ability to weave a tale has never been better. Imaginative and uniquely original, Vance sets the table for decades of speculative writers since.

The heart of this work is Vance’s characterization. Introducing characters like Liane the Wayfarer and Chun the Unavoidable, Vance crafts a kaleidoscope of personalities that revolve in a dynamic tension that brims with vitality and weird life.

Finally, this is a demonstration of Vance himself. This is something like watching a foreign film and being fascinated by the action but being unable to completely follow the dialogue. Vance’s genius is Fellini like in its originality and distinct character.

-

I lived beside the ocean — in a white villa among poplar trees. Across Tenebrosa Bay the Cape of Sad Remembrance reached into the ocean, and when sunset made the sky red and the mountains black, the cape seemed to sleep on the water like one of the ancient earth-gods ... All my life I spent here, and was as content as one may be while dying Earth spins out its last few courses.

Two bright stars on the science-fiction / fantasy firmament have gone to sleep: Jack Vance and Iain M. Banks. I know of no better way to honour them than to go back to their imaginary worlds and spend some quality time there, like a couple of old friends sharing a dram and reminiscing about the good old days and the crazy adventures we've been through in our youth.

I've been aware of The Dying Earth for years, it's been often mentioned as a defining moment in the history of speculative fiction, one of the foundation stones supporting a whole modern edifice of stories and autors for whom mr. Vance is an inspiration. I kept putting it off not out of reservations about it being dated or overrated, but like a collector who keeps a good bottle of wine for a special occasion or for a rainy day, when the blues gets to you and you start to wonder what's the point of all this reading.

The point in case is imagination - it is like a muscle that needs to be exercised regularly and given proper, wholesome food or it will shrivel and grow cynical and bitter. There is more wonder, poetry and a sense of adventure in this slim opening volume than in many so called epic doorstoppers published recently. The secret ingredient that colours every landscape and every character portrait is a deep seated melancholy, an awareness of the fragility of life and the 'unavoidable' coming of Death. The scenery plays as much a role in the story as the heroes who move like ants among gigantic ruins.

A dim place, ancient beyond knowledge. Once it was a tall world of cloudy mountains and bright rivers, and the sun was a white blazing ball. Ages of rain and wind have beaten and rounded the granite, and the sun is feeble and red. The continents have sunk and risen. A million cities have lifted towers, have fallen to dust. In place of the old peoples a few thousand strange souls live. There is evil on Earth, evil distilled by time

The end of times is closer to a whimper than a bang, despite what the summer blockbuster movies predict every year. The Sun is tired, the Earth is tired, the people are tired. Yet, like the indian summer returning in one glorious fire for one last time before the coming of winter, the plant and animal life burst into incredible shapes and lush, exotic colours, wild magic replaces the rigid laws of physics (although Vance proposes mathemathics as the original source of spells) and wild carnivals roam the streets of the last cities of Man.

In a development similar to Fritz Leiber and to other writers of the period, the genesis of the book and the setting came through short stories offered to fanzines and literary magazines. Also in a sign of the times, the magic intensive fantasy world receives a scientific angle that allows it to reach out to more hardcore SF fans. The ambiguous nature of the main characters, none of them clear cut good or bad, gives the book a modern feel by moving away from the 'knight in shining armor' or 'evil overlord' stereotypes often associated with classic fantasy. The first set of six stories is loosely tied together by recurring characters and a common geographical location.

1 - Turjan of Mir - is a mix of science and magic, crossing over effortlessly between the tropes of SF and fantasy, a trend that will continue in later stories. Turjan is a magician, hoarding the last known spells preserved from the vast knowledge of his forebears. He also dabbles in genetics, using a cloning vat to try to grow up human beings. In a move that predates the rules of Dungeons & Dragons role playing games, he can only store up to four spells at a time in his mind, learned from books and forgotten after use. In a move that prefaces the psychedelic mind blowing trips of the 1960's, he sets out on a quest to find the greatest magician of his time, Pandelune, who lives in a hidden many-coloured realm of vermillion skies and turquoise forests. There he meets T'sais - a fiery amazon whose mind cannot differentiate between good and evil, beauty and ugliness. Pandelune sends him on another quest for a priceless magical artefact and Turjan has to use both his sword and his sorcerous spells. All of this in just the first short story, delivered in flawless prose.

2 - Mazirian the Magician - is an even more powerful sorcerer than Turjan, capable of holding six spells in his mind instead of four, questing after the same secret genetic recipes. His garden is another place of wonder, on the edge of a dark and foreboding forest, home to monsters and dangerous places and to one secretive amazon who taunts Mazirian daily by coming close and then evading his spells and escaping back into the trees. An epic chase between the two will satisfy the most ardent action movie junkie.

3 - T'sais - is the twisted amazon from the first story, who leaves the safe haven of Pandelune's realm and comes to Earth to learn about love and self-control. She comes across another tormented soul, a man cursed by his own wife to wear the face of a demon. The highlight of the story is a Walpurgis night the two are witnessing, a macabre festival of witches, demons and lubricity.

4 - Liane the Wayfarer - is an evil trickster, the prototype of the thief from the above mentioned Dungeons & Dragons lore, a sharp dresser in primary colours, a smooth talker always with a knife behind his back. He is not immune to love though, and when he meets the witch Lith he sets out on yet another quest in order to gain her attention. Among the wonders we see is the white city of Kaiin, where sorcerers gather at an inn to decry the sorrowful state of their art and daze each other with minor feats of magic. Later Liane explores a ruined temple and meets Chum the Unavoidable, the avatar of Death.

5 - Ulan Dhor is a young sorcerer apprentice (notice the presence of magic in every story) who is sent to recover the greatest magic spell from a distant island. The spell is written on two stone tablets, each controlled by a fanatical religious sect. A lucid and bleak analysis of intransigence and brain washing is coupled with a high octane chase across the skyscrapers dotting the island and with a possible romance for Ulan. This fifth story has the most overt scientific references (anti-gravity, airplanes, nanotechnology) in a post-apocalyptic setting. It reminded me a lot of the Robert E Howard pulps.

6 - Guyal of Sfere - closes the collection and is my favorite in a difficult to decide contest, where each story tries for the top spot. It is also the most archetypal, mythical, timeless concept : a young man's journey in search of wisdom. He caparisoned the horse, honed the dagger, cast a last glance around the old manse at Sfere, and set forth to the north, with the void in his mind athrob for the soothing pressure of knowledge. Guyal is a defective human being in the eyes of most of his contemporaries. Instead of accepting the inevitable doom with resignation and epicurean lassitude, he is constantly asking questions : Why this? Why that? Where do we come from? Where are we going? What is there to find beyond the horizon?

'Why strive for a pedant's accumulation?' I have been told. 'Why seek and search? Earth grows cold; man gasps his last; why forego merriment, music, and revelry for the abstract and abstruse?'

The answers may be provided by the all-knowing Curator of the Museum of Man, at the end of a torturous journey across mountains and tundra. Guyal is helped along by three magical artefacts, a gift from his father : a spell of protection, a magic sword and a self inflating, unbreachable tent. The journey has about everything: like Ulysses he escapes enchantment through music, like Perseus he rescues a damsell in distress and later fights a gorgon - a creature from the demoniacal dimensions that threatens the ruined museum and demands human sacrifices. You see what I mean about archetypal heroes. The reason I prefer this story is probably the fact that it is the most optimistic one : instead of turning the eyes inward and contemplating destruction, Guyal is raising his head, staring at the promise of distant stars. With the romantic angle added, I'm thinking now of another classic SF story - Logan's Run.

There are no big wars or complicated political plots in this novel, the author preferring instead to focus on individual destinies, yet I would still call the work epic in its scope, as the single threads mesh together into a majestic vista. I will add new threads( like the witch Lith weaving her golden tapestry) as I read the next three books in this setting. -

Let's do some quick math. Jack Vance's The Dying Earth was originally published in 1950. I was born in 1969. I first started playing Dungeons and Dragons, in earnest, in 1979. It is now 2014. On second thought, screw the math. You can plainly see that my reading of The Dying Earth is tardy, given that Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson cited Vance's work as influences on the development of the Dungeons and Dragons game.

And how.

More than an influencer, The Dying Earth is a wholesale supplier of D&D wares. In the first story, "Turjan of Mir," we see something akin to alignment, the fact that wizards must memorize their spells from spellbooks, the limitation (which I always thought was a rule to add game balance - I was wrong) that mages can only memorize so many spells a day, and at least one spell that was almost lifted verbatim from Vance to Gygax and Arneson (the Excellent Prismatic Spray, which appears in D&D as "Prismatic Spray," unless it is cast by one of the wizards

Bill or Ted, in which case it is the "Most Excellent Prismatic Spray, Dude").

Now, that's not to say that The Dying Earth is one long hack-and-slash D&D adventure. Far from it. Vance is a far more sophisticated writer than Gygax or even Arneson (who, in my humble opinion, is the better of the two - compare Arneson's wrting on his

Blackmoor campaign with that of Gygax's

Greyhawk campaign setting. Gygax had more stuff, Arneson had better original writing). So don't go in expecting a Choose Your Own Adventure. Vance is choosing the adventure for you, and his characters and their quests are meant to be read, not played. These characters, in these situations, would crumble in the hands of a lesser artist (like the 12 year old me that would have tried to create D&D stats for these characters and sent them on a killing spree through a non-descript dungeon crawl).

I will admit that the first couple of stories were a bit trite. The thin plot devices and moralistic tales read more like a poorly-copied fairy tale than a good work of fantasy. I'd love to know the order these stories were written in, as they got better as the book progressed. By the end, they were outstanding.

The second-to-last story in the book, "Ulan Dhor," follows the journey of the titular novice sorcerer in his quest for the lost city Ampridatvir, once ruled by Rogol Domedonfors, a wizard of great power. Ulan Dhor is sent there by his mentor, Kandive, to recover the lost magic of Rogol Domedonfors by bringing together two tablets which, when combined, will restore the magical power that once held sway in the city. Along the way, he encounters a strange culture and even stranger magic - the magic of the ancients that once held sway before the sun began its slow death. One can see that this story might have influenced M. John Harrison's

Viriconium or Jeffrey Ford's

Well-built City.

The final, longest, and most compelling story, "Guyal of Sfere," follows another adventurer on a quest to find the Museum of Man to speak with the Curator, from whom Guyal wishes to gain knowledge. Again, the seeker travels into strange lands, encountering strange customs and cultures, in a story that is, at first, less about the magic (though magic does play a part) and more about the men and women Guyal meets in his journey. Only when Guyal and his new travelling companion, Shierl, make their way into the Museum of Man does magic play a major role. And this is strange, strange magic, of the kind that would fascinate nerds like me for decades to come. There is a hint of absurdism in the tale, which reinforces the bizarre feel of the story. Suffice it to say that we encounter one of the most disconcerting demons I have ever had the dis-pleasure of reading about - which is saying something, given my . . . particular . . . reading tastes. I could see this story influencing

Gene Wolf's Book of the New Sun and, to some extent, Book of the Long Sun, which could make for some compelling historical analysis (of which I am not capable).

What started out as a not-particularly-spectacular read ended up as something excellent. I will be reading more of Vance's work, not because it's assigned reading for a class in Dungeons and Dragons history (for which I was really tardy), but because the writing in the last half of the book was excellent, the characters less shallow than much of modern fantasy, and the strangeness endearing to this strange reader. -

Strange to think that this was the series that inspired

Martin and

Wolfe in their fantasy endeavors. Going from their gritty, mirthless rehashes of standard fantasy badassery to Vance's wild, ironic, flowery style was jarring--going directly from Anderson's grim, tragic

Broken Sword to this was tonal whiplash.

At first I didn't know what to make of it: the lurid,

purple prose, the silly characters, the story which jumped from idea to idea with abandon. I mistook it at once for the unbridled pulp style of early century genre authors like A. Merrit or

Van Vogt, but soon it became clear that there was something more complex at work.

Vance is rushing from one idea to the next, heedless of contradiction or pace, but it is not merely an unbridled mind on a romp. It is a style recognizable to any scholar of Fairy Tales, or of the Thousand and One Nights, where absurd characters and situations are paraded before the reader as wry commentaries--subversions of social mores and preconceptions. Vance's characters are not psychological studies, not realistic, but archetypal and foolish, traipsing from one peril to the next and then back out again, in the vein of Lewis Carroll.

Yet Vance is not as wild as Carroll or Peake, not as unpredictable or insightful. He has some shining moments, but I did not find that they entirely excused the broken pacing and shallow characters. The tongue-in-cheek reversals were simply not constant enough to make the world suitably subversive.

Yet there still remains an original voice and vision here which has been very influential--though not always fruitfully. As someone who grew up in basements playing old Dungeons & Dragons modules (and even designed

a parody of them), it became immediately clear to me where Gygax had taken his inspiration. From the endless series of strange wizards vying for power to the nonsensical dungeons where one might face a giant demon head, a talking crayfish, an Aztec vampire, and an evil chest one after the next, I was immediately stricken with an uncomfortable nostalgia.

Yet Gygax--like Wolfe and Martin--was unable to reproduce any of the wit or joy of Vance's creation, though whether they didn't recognize it or were merely incapable of recreating it I cannot say. In any case, I find it disappointing that so few authors have tried to mimick the sheer, ironic pleasure with which Vance comported himself. I know Pratchett tried to do something similar in his work, but sadly, I've never found his writing funny.

Then again, many fantasy authors are desperate to prove themselves 'mature authors in a mature genre', but as

C.S. Lewis knew, the rejection of childlike mirth is the sign of adolescence, not adulthood.

Somewhat problematic in Vance's work, though not as bad as many later genre authors, is the secondary roles he gives to women. It seemed particularly glaring at first, since it opens with male wizards creating and chasing around beautiful, naive women, and the only strong woman is an aberrant creation who is easily talked down and made to change her mind. Yet the men are also often fools and simply swayed, as is the nature of a Fairy Tale, so there is some more equality there.

Beyond that, the descriptions of men versus women are often treated differently, with women being described physically and in terms of their beauty and while a man is rarely described as a physical presence at all. This is only Class I gender inequality, and nearly ubiquitous in genre writers, but a part of me hoped that Vance might let his unfettered exploration of concepts spill over and subvert the characterization of women, but it was not to be.

In many ways, Vance can be seen to represent a middle ground between the unhinged visions of Carroll and Peake and the more straightforward authors of the genre, but as it went on, I began to wish that Vance would distinguish his work more--either by making it more wild and hallucinogenic, or by making it more structured and purposeful. As it was, I felt he too often inhabited a middle ground which was easily muddied by imprecision.

My List of Suggested Fantasy Books -

1950, a time of transition from swashbuckling square-jawed heroes with huge brains and spaceships falling headlong into a deep future world where everyone is surrounded by death, old tech indistinguishable from magic, and to make things worse, the sun is dying. This is the last hurrah of Earth and it seems that everyone is trying to make the most out of it, grognak the barbarian style.

What? Isn't this SF? Sure! But it's still pretty much entirely classic Sword and Sorcery. We've got curses and transformations, 50's style misogyny, master wizards and apprentices of maths and old tech, thieves and warriors. I can't help but think it'd make, with a bit of good retooling, a fairly interesting SyFy production.

Nothing big budget, though.

Some of the ideas are pretty standard science rah-rah, getting your life back on track rah-rah, and being your best before it all ends, which is a pretty cool message after coming out of WWII and wanting to dive into a bit of imaginative science fantasy, but let's face it, we've all seen movies as good along these lines, or it's equivalents, all throughout the decades since.

I'm not saying this is a bad collection of short stories all placed in a similar setting and the same time, because it isn't bad at all. It's a serial adventure with different characters and it shows us something really interesting about the days in which this was published. Like the fact that short story authors could actually make something of a living once upon a time. What fantasy that is!

Seriously, it's good sword and sorcery in a SF backdrop, and if you're in the mood for something like that, you really can't go wrong with picking this classic up. -

To read The Dying Earth by Jack Vance is like to find oneself inside the fabulous canvas painted by some artist exiled to the end of the fatigued time… Or in the garden of paranoia…

Deep in thought, Mazirian the Magician walked his garden. Trees fruited with many intoxications overhung his path, and flowers bowed obsequiously as he passed. An inch above the ground, dull as agates, the eyes of mandrakes followed the tread of his black-slippered feet. Such was Mazirian's garden—three terraces growing with strange and wonderful vegetations. Certain plants swam with changing iridescences; others held up blooms pulsing like sea-anemones, purple, green, lilac, pink, yellow. Here grew trees like feather parasols, trees with transparent trunks threaded with red and yellow veins, trees with foliage like metal foil, each leaf a different metal – copper, silver, blue tantalum, bronze, green indium. Here blooms like bubbles tugged gently upward from glazed green leaves, there a shrub bore a thousand pipe-shaped blossoms, each whistling softly to make music of the ancient Earth, of the ruby-red sunlight, water seeping through black soil, the languid winds. And beyond the roqual hedge the trees of the forest made a tall wall of mystery. In this waning hour of Earth's life no man could count himself familiar with the glens, the glades, the dells and deeps, the secluded clearings, the ruined pavilions, the sun-dappled pleasaunces, the gullys and heights, the various brooks, freshets, ponds, the meadows, thickets, brakes and rocky outcrops.

But the denizens of this fantastic world remain mischievous and frivolous and there is no greater fun for them then some magic frolics.

Fantastic thoughts can only emerge from the fantastic mind… -

This was AMAZING. I fell in love with Jack Vance reading this novel and I can not for the life of me understand why I never read any Jack Vance before. I blame myself and the entire world for this oversight and I intend to correct the problem immediately. What an amazing combination of condensed writing and huge amounts of story. I can't believe this is only 156 pages long and yet Vance left no stone unturned as far as telling a complete story. I am off to read more Vance.

-

There isn’t any other book is SF/Fantasy quite like Jack Vance’s The Dying Earth, published as a cheap 25 cent paperback back in 1950 by Hillman Publications. I wish it had been picked up by Ballantine Books and published along with some other early classics of the early 1950s like The Space Merchants, Childhood’s End, More Than Human, Fahrenheit 451, Bring the Jubilee, etc.

Despite this, the book has had an enormous influence on writers ranging from Gene Wolfe and George R.R. Martin to Gary Gygax, the creator of Dungeons & Dragons. In fact, the influence of Vance on Gygax and D&D is so obvious that he really deserved a cut of all the proceeds from that once-mighty franchise. Anyone who has played D&D will immediately recognize the idea that magicians can only memorize a few spells at a time (which takes great effort), and forget immediately after casting them. Even better are the crazy spell names that Vance has concocted (The Excellent Prismatic Spray, Phandal’s Mantle of Stealth, Spell of the Slow Hour, etc).

Of note, Wikipedia indicates that Vance himself was influenced by earlier fantasy writers like H.G. Wells (The Time Machine), William Hope Hodgson (The House on the Borderland, The Night Land), Clark Ashton Smith (Zothique stories), and Edgar Rice Burroughs (Barsoom series). I haven’t read any of those writers other than Wells, but they sound like pretty good company.

Since all art takes its inspiration from earlier works, it’s not a knock on Jack Vance that he shows his influences quite clearly. Instead, he deserves great credit for taking those earlier stories and giving them entirely new life though his amazing imagination, precise yet baroque writing style, and somewhat archaic dialogue that disguises an incredibly dry wit and skeptical view of humanity. I’ve read SF and fantasy all my life, and I can say with confidence that his voice and imagery are unique. If you’ve encountered anything like it, it’s most likely that those writers took their cue from Vance.

The book is very short (around 175 pages), and is actually a collection of six slightly overlapping but self-contained stories set in an incredibly distant future earth where the sun has cooled to a red color, the moon is gone, and humanity has declined to a pale shadow of former greatness, and struggles to survive amongst the ruins of the past. The world is filled with various magicians, sorcerers, demons, ghouls, brigands, thieves, adventurers, etc. The events are episodic but are compulsively readable, and really beautifully written. The sense of melancholy and decline are ever-present, yet the characters themselves are not cowed by this situation, and strive to achieve their own goals even as the world moves toward a time when the sun will eventually snuff out like a candle. Despite this, many of the situations they find themselves in are quite funny, in a dark and ironic sort of way.

The Dying Earth was later followed by The Eyes of the Overworld in 1966 (featuring Cugel the Clever) and two further sequels, Cugel’s Saga in 1983 and Rhialto the Marvellous in 1984. They are collected in the omnibus volume Tales of the Dying Earth, and it is a treat to be able to read them in succession with no gap it time. Unlike many other classics, the book has not aged at all because it occupies a place outside of time, where science and magic mix together with entropy, quirky characters, and vivid adventure for a unique world vision. -

“Earth,” mused Pandelume. “A dim place, ancient beyond knowledge. Once it was a tall world of cloudy mountains and bright rivers, and the sun was a white blazing ball. Ages of rain and wind have beaten and rounded the granite, and the sun is feeble and red. The continents have sunk and risen. A million cities have lifted towers, have fallen to dust. In place of the old peoples a few thousand strange souls live. There is evil on Earth, evil distilled by time…Earth is dying and in its twilight…”

-

I've known for quite a while that George RR Martin thinks highly of Jack Vance and The Dying Earth and last year I had the opportunity to read his anthology,

Songs of the Dying Earth, where a number of authors wrote short stories set in The Dying Earth.

I loved it. It remains, and easily so, the best anthology I've ever read. And that only meant one thing, I had to read the original tales.

I'm also very glad I read the anthology, even though one of the stories in The Dying Earth was spoiled a bit by it (actually, the title alone spoiled the story, but not bad at all). It was great to have an understanding of some of the world, the peculiar wordings, and some of the creatures. This usually isn't a problem, and I don't think will be for you, it's just that audiobooks make it harder to get into something that takes a while to explain things.

With my busy schedule (graduating law school Saturday, studying for the bar, my wife was just put on bed rest and we have a two-year-old, and twins in August...hopefully), I don't always have time to read everything I would like to, so I've become a huge supporter of audiobooks. This gives me somewhat of a chance to make a dent in my to-be-read pile.

With that in mind, the narrator can make or break a book sadly, but The Dying Earth's narrator was pretty much perfect for the job. This is a unique place and deserves a unique voice for all its characters and the land.

The Dying Earth is one of those magical places that doesn't exist in this new age of gritty, realistic fantasy. The dialogue is clever and full of vocabulary words to look up. Luckily I've read Steven Erikson, not to mention the anthology mentioned above, for some heads up.

The land is full of fantastic beasts and peoples and wizards and magic. The spells are so complicated, a wizard can only keep up to five in his or her head at a time. The story is full of riddles and extraordinary circumstances and I may have mentioned this before...magic.

This is the first book in The Dying Earth series of four books, called simply The Dying Earth. Instead of one long narrative it's just a collection of short stories that are loosely connected by the land of the dying earth and the stories are titled by the character the story follows.

As I understand it, the rest of the books in the series are also short stories collected into one volume, but unlike this first volume, the rest of the books each follow a certain character for the entire book. I'll keep you updated as I continue.

Do yourself a favor and pick up The Dying Earth. I know gritty and real are the buzzwords of the day, but while The Dying Earth is nothing of the sort, it's full of magic and whimsy and now I realize how good of a job the authors of Songs of the Dying Earth actually did.

The Dying Earth ToC:

Turjan of Miir

Mazirian the Magician

T'sais

Liane the Wayfarer

Ulan Dhor

Guyal of Sfere -

6.0 stars. One of my "All Time Favorite" novels. Jack Vance is one of the "undisputed" masters of the golden age of science ficiton and this may be his greatest work (though I have not yet read them all). The world Vance creates in this collection of linked stories is as good as it gets and the characters who inhabit it are all fun and original. I was absolutely blown away by it.

HIGHEST POSSIBLE RECOMMENDATION!!

Nominee: Hugo (Retro) Award for Best Science Fiction Novel. -

ORIGINALLY POSTED AT

Fantasy Literature.

The Dying Earth is the first of Jack Vance’s Tales of the Dying Earth and contains six somewhat overlapping stories all set in the future when the sun is red and dim, much technology has been lost, and most of humanity has died out. Our planet is so unrecognizable that it might as well be another world, and evil has been "distilled" so that it's concentrated in Earth's remaining inhabitants.

But it's easy to forget that a failing planet is the setting for the Dying Earth stories, for they are neither depressing nor bleak, and they're not really about the doom of the Earth. These stories are whimsical and weird and they focus more on the strange people who remain and the strange things they do. Magicians, wizards, witches, beautiful maidens, damsels in distress, seekers of knowledge, and vain princes strive to outwit each other for their own advantage.

What appeals to me most is that The Tales of the Dying Earth are about how things could possibly be in an alternate reality. All speculative fiction does that, of course, but Jack Vance just happens to hit on the particular things that I find most fascinating to speculate about: neuroscience, psychology, sensation, and perception. These are subjects I study and teach every day, so I think about them a lot. One thing I love to consider, which happens to be a common theme in Vance’s work, is how we might experience life differently if our sensory systems were altered just a bit. I find myself occasionally asking my students questions like "what would it be like if we had retinal receptors that could visualize electromagnetic waves outside of the visible spectrum?" (So bizarre to consider, and yet so possible!) They look at me like I'm nuts, but I'm certain that Jack Vance would love to talk about that possibility. And even though The Dying Earth was first published in 1950, it doesn’t feel dated at all — it can still charm a neuroscientist 60 years later. This is because his setting feels medieval; technology has been forgotten. Thus, it doesn’t matter that there were no cell phones or Internet when Vance wrote The Dying Earth.

I also love the constant juxtaposition of the ludicrous and the sublimely intelligent. Like Monty Python, Willy Wonka, and Alice in Wonderland. [Aside: This makes me wonder how Johnny Depp would do at portraying a Jack Vance character…] Some of the scenes that involve eyeballs and brains and pickled homunculi make me think of SpongeBob Squarepants — the most obnoxious show on television, yet somehow brilliant. (Jack Vance probably wouldn't appreciate that I've compared his literature to SpongeBob Squarepants. Or maybe he would!)

Lastly, I love Jack Vance’s “high language” (that’s what he called it), which is consistent and never feels forced. This style contributes greatly to the humor that pervades his work — understatement, irony, illogic, and non sequiturs are used to make fun of human behavior, and I find this outrageously funny. As just one example, in one story, Guyal has been tricked into breaking a silly and arbitrary sacred law in the land he’s traveling through:

“The entire episode is mockery!” raged Guyal. “Are you savages, then, thus to mistreat a lone wayfarer?”

“By no means,” replied the Castellan. “We are a highly civilized people, with customs bequeathed us by the past. Since the past was more glorious than the present, what presumption we would show by questioning these laws!”

Guyal fell quiet. “And what are the usual penalties for my act?”…

“You are indeed fortunate,” said the Saponid, “in that, as a witness, I was able to suggest your delinquencies to be more the result of negligence than malice. The last penalties exacted for the crime were stringent; the felon was ordered to perform the following three acts: first, to cut off his toes and sew the severed members into the skin at his neck; second, to revile his forbears for three hours, commencing with a Common Bill of Anathema, including feigned madness and hereditary disease, and at last defiling the hearth of his clan with ordure; and third, walking a mile under the lake with leaded shoes in search of the Lost Book of Kells.” And the Castellan regarded Guyal with complacency.

“What deeds must I perform?” inquired Guyal drily.

If you want to find out what three deeds Guyal had to perform, you’ll have to get the book!

I listened to Brilliance Audio’s production of The Dying Earth and the reader, Arthur Morey, was perfect. He really highlighted the humorous element of Vance’s work. It was a terrific production and I’m now enjoying the second Dying Earth audiobook (which is even better than this first one!). By the way, I want to say that I’m extremely pleased with Brilliance Audio for publishing these stories!

Jack Vance is my favorite fantasy author. His work probably won’t appeal to the Twilighters, but for those who enjoy Pythonesque surreal humor written in high style, or for fans of Lewis Carroll, Fritz Leiber, and L. Frank Baum, I suggest giving Jack Vance a try. If you listen to audiobooks, definitely try Brilliance Audio’s version! -

“ Here is all the lost lore, early and late, the fabulous imaginings, the history of ten million cities, the beginnings of time and the presumed finalities; the reason for human existence and the reason for the reason.”

Jack Vance’s classic 1950 novel, The Dying Earth, is a strange and wondrous collection of six interwoven stories that take place in a future so distant that the Earth itself is dying as the sun reddens and slowly gutters out.

Initially I bought this book because of the enormous influence it’s had on some of my favorite writers and their work, especially Gene Wolfe’s utterly ingenious and criminally under-read The Book of the New Sun, possibly my all-time favorite sff cycle; M. John Harrison’s baroquely poetic and beautifully bizarre Viriconium series; and, more recently, works like N.K. Jemisin’s brilliantly conceived The Broken Earth, by far my favorite trilogy in recent years. And these are but a few examples of the multitudes of authors and titles that have been inspired and influenced, directly or indirectly, by Vance’s far-future science-fantasy masterpiece and the subgenre it spawned.

So as I said, my initial motives for reading The Dying Earth were ulterior, and thus external to the work itself, focused as I was on seeing it through the eyes of other authors and divining what is was that they saw in it. But soon enough I had myself fallen under the book’s spell, no longer searching for vestiges of places or characters which may or may not have made it into the text of Wolfe’s Claw of the Conciliator, or inspired this or that scene in Harrison’s A Storm of Wings. And at this point I was no longer reading it simply because of all the great writers it’s influenced, but for the sheer pleasure that reading it affords—without any need for extrinsic reason or reference.

As previously noted, the novel consists of six interwoven stories—more like fables, really—which for the most part follow the age-old formula of the hero’s journey (though two of the stories feature a villain rather a hero at their center). The fact that the tales are somewhat formulaic, and unambiguous enough to speak so straightforwardly about “heroes” and “villains” (which are almost always made pretty explicit right from the outset), somehow didn’t detract one whit from the fascination, enjoyability, pathos, and occasional beauty I discovered within the pages of this book. If anything, it actually tended to reinforce these delights. Possibly this is due the power of the archetypal templates which undergird so much of these stories’ architecture, and how deeply carven into our collective unconscious these “universal symbols” are, that when we experience a unique and creative derivation of them—such as Vance gives us here—it pushes on all the right pleasure centers in these ancient, animal brains of ours. But that’s just a whole lot of conjecture; or, in other words, rubbish, dreck, dross, bunk, malarkey. More likely—or more simply put, anyhow—is that they’re just great stories, written by a great author.

A bit about the plot:

Though set billions of years in the future, the world of The Dying Earth is dominated not by super-advanced technology, but instead by magic and sorcery, which much of the time lends it the unmistakable feel of fantasy (hence the term science-fantasy used to describe this and other books of its ilk). The desired ends of some of the magic being done are more recognizably modern and scientific than others. For example, the first story centers on a character named Turjan of Miir (basically someone we might call a geneticist and biochemist, though a totally loopy one) who is trying to endow the vat-grown humans he makes in his lab with life and intelligence. But his creations are always lacking some vital spark, so he seeks out Pandelume, a Pygmalion-like figure living on a different planet (or possibly different dimension, world, or even plane of existence), who may be able to help Turjan with his work.

In a later story—my favorite of the bunch, titled T’Sais after its titular heroin—Vance explores an existential crisis experienced by T’Sais, after her worldview is challenged (she’s one of Pandelume’s vat-grown Galateas), and follows her on her subsequent search for beauty and meaning in an often harsh world. This story is powerful and brilliantly conceived, and examines questions of free will, humanity (and its parameters), existence, death, love, hate, beauty, meaning, and the right to life.

In yet another story, a man is sent to an ancient city in order to retrieve a powerful relic for his uncle, and while there encounters crumbling skyscrapers, flying cars rusty from disuse, and anti-gravity mechanisms. All of which strike him—understandably, as someone who has only ever ridden horses and lived in stone castles—with absolute awe. This story is probably the most “science fictional” of the lot.

My second favorite story, after T’Sais, is about a young man, Guyal of Sfere (and is called....Guyal of Sfere!), who grows up with boundless curiosity about the world around him, and spends his days peppering his father and anyone who will listen with innumerable questions. When Guyal reaches adulthood, his father finally comes to terms with the fact that this insatiable curiosity is an inextricable part of his son’s nature, and so helps him embark upon a quest to find an Oz-like personage who supposedly has knowledge of all things, and thus will have the answers to all Guyal’s questions. This person is known as the Curator, and resides in a famed, ancient, and semi-mythical place called the Museum of Man. Obviously, many unforeseen difficulties arise along the way (after all, it’s not really a quest without some unforeseen challenges), as well as a chance encounter that unexpectedly but fortuitously pairs Guyal with an intelligent and capable female partner, who works with him in the quest to find the elusive Curator and his mysterious Museum of Man.

Though I did inevitably like some stories more than others, the overall level of quality throughout the book was impressive, and I came away loving it, and understanding why so many others have loved it too, finding inspiration in it in the almost three-quarters of a century(!) since it was first published.

4.5 stars rounded up to 5 because . . . well because it’s Jack Vance! Come on, you think I’m gonna give less than 5 stars to Jack freaking Vance?? -

The Dying Earth is an undisputed classic work of science-fantasy; everyone from Dean Koontz to Neil Gaiman has cited it as an important influence, and George R.R. Martin edited an anthology of original stories from some of the brightest stars in the field in honor of it and Vance. I read it many years ago and was suitably impressed, but recently listened to this audio version on a long drive with my wife and was disappointed. I thought the performance sounded unenthusiastic and uninspired, and my wife said it was downright misogynistic in places. It's a well-written portrait of a far-future world where magic has replaced science and has some interesting situations and characters, but it didn't really capture me this time around. Maybe it hasn't aged well, or maybe it's one of those stories that only works on paper.

-

Dopo la lettura di Lyonesse di qualche anno fa, ho riprovato a leggere Jack Vance con questo suo famosissimo ciclo della Dying earth, sperando in miglior sorte rispetto al tentativo precedente.

Ho ritrovato la stessa splendida scrittura - malinconica, suadente, ricca, evocativa - ma anche lo stesso obsoleto modo di fare fantasy, ormai davvero anacronistico.

Ho deciso di interrompere la lettura al terzo racconto, dato che questi non aggiungevano nulla di più a quel Vance che già avevo trovato nell'intero volume di Lyonesse.

Ho invece tentato con il romanzo breve inserito alla fine del volume: La Falena Lunare (The Moon Moth). Romanzo estraneo al ciclo di La Terra morente.

Per fortuna questo breve romanzo (o racconto lungo?) risolleva le sorti del libro (un plauso ad Urania per averlo inserito). Il romanzo mi ha davvero convinto per contenuti oltreché per stile; ha un world building sofisticato, notevole, un'idea davvero riuscita. Se vi capitasse per le mani questo "The moon moth" dategli una possibilità, non ve ne pentirete. -

I had never heard of Jack Vance until Subterranean Press announced it would be publishing

a tribute anthology containing stories from some of my favourite authors. Apparently Vance is a master fantasist, on par with Tolkien, and his Dying Earth series inspired all of those authors, and many more, in the latter half of the twentieth century. So I ordered the massive volume from Subterranean Press, and then I set about finding a copy of the original book that started it all. Since then, Vance has led to nothing but surprises.

The first surprise was the length of The Dying Earth. This is a thin book. I was expecting something epic, not quite doorstopper (for I'm aware that they did not publish doorstopper fantasy in those days, Tolkien excepted), but something with more presence. That was my mistake, for I am young and unfamiliar with the pulpiness of paperbacks from that era, even British reprints from the 1980s.

The second surprise was the serialized nature of the novel. Either I missed that part when reading about it, or no one deigned to mention that The Dying Earth is actually a collection of episodic shorts rather than a continuous narrative. Not that there is anything wrong with this, but I think that jarred me when I began reading.

And then I began reading.

There is so much to praise about The Dying Earth. Vance has a deft touch when it comes to names, places, and descriptions. His characters have odd-sounding monikers and come from odd-sounding places; the times they inhabit are odder still. Above all, his stories are whimsical in a way that transcends any merely-adequate work of fantasy. His magicians and sorcerers dabble with demons and spirits; his thieves stumble across artifacts of power and cross paths with princes and scholars. Vance has created a world where not only anything can happen but you, while reading it, believe that anything can happen—and eventually, it probably will.

Vance's mastery lies in his ability to create the sense of difference essential to works of speculative fiction. And I see why he is considered one of the greats of this field and why his books are held up as paradigm examples. We are lucky enough to be experiencing a glut of fantasy, and a lot of it is derivative. I can forgive those poor uninitiated who, having cracked open a fantasy novel at the bookstore, conclude that the entire genre is nothing more than

"medieval Europe with magic". The Dying Earth is most certainly not that. Instead of presenting a poor analog of our world and adding magic, Vance takes us far into the future, where magic has superseded technology (or assimilated it, if you will) in the waning days of this planet. He gives us vat-grown clones, instantaneous transportation across the face of the Earth and between planets, fantastic flying machines, and of course a broad gallery of interesting new animals and creatures to populate his Dying Earth. Deodands, plegranes, and grues—oh my!

And yet.…

And yet, I cannot give this book three stars. From an academic perspective, I can appreciate Vance's skill. But I just did not enjoy the book as a reader. The Dying Earth is an intricately constructed palace, one which I would love to view from afar. But, like Camelot, it is only a model.

We've all had this feeling before. We read something that people we trust, whether they are bestselling authors or just our best friends, recommend with a fervour and zealousness that is, at times, a little scary. And we don't like it. So we wonder: is there something wrong with us, that everyone else can enjoy this book while we remain unmoved? I am never satisfied by simply saying that my mileage varies, that everything is subjective. I am curious; I want to analyze my discontent and understand what makes me different from those who swear by Jack Vance and his Dying Earth.

Most obviously there is a generational gap between me and the various authors who were inspired by Vance. I have grown up in a literary world very different than the one that educated those authors, thanks in part to their own contributions before I was born and then during my childhood. George R.R. Martin had no George R.R. Martin to hook him on the political intrigue of A Song of Ice and Fire. So I have been exposed to a different set of formative fantasy texts, and for that reason, Vance's effect on me is different.

I won't go so far as to claim that the generation gap is the entire reason. I am sure there are many people my age who have fallen in love with Vance's stories. I have several friends who play Dungeons & Dragons, and they might find his stories more entertaining than I did. In addition to the differences in literature between when I grew up and these Vance fans did, there are also just differences in mood and mentality.

For instance, I have terrible trouble visualizing events. When I read, I seldom picture the story in my head. If I do, characters are mere human-shaped blobs; I don't see faces. Visualizing, for me, ends up more like a radio play than television. So I tend to prefer dialogue to description, action to imagery. I can recognize Vance's penchant for the latter, but a lot of it is lost on me. And I cannot keep his aeons and his places straight for the life of me (I love that maps have become commonplace at the front of newer fantasy). In this respect, The Dying Earth required more effort from me than, shall we say, more straightforward of fantasy.

So I will reserve myself from making a recommendation for or against Jack Vance. I think his vast oeuvre and acclaim speaks for itself, and you would probably be very unwise to ignore him once, like me, you discover his existence. Maybe you will pick up an old paperback copy of one of his earlier books and fall in love and devour everything else he has written. Or maybe, like me, you will read The Dying Earth, recognize a master at work, but sadly be deprived of joining the club. Because you can choose what you appreciate and what you celebrate, but you cannot choose what you love. -

Meh, what on earth?

I went into the book expecting to like it, and it is nice and short, but after a good start it just went downhill for me. The first couple of stories about a wizard and two identical girls created by magic are great, but the subsequent stories just bored me. The prose is nice and elegant but sometime the extreme eloquence just leave me floundering. Also, in this cynical day and age the Abracadabra! (not to be confused with the more lethal Avada Kedavra) kind of unsystematic magic just does not cut it for me any more. My fault I guess, I just can not suspend disbelief when a wizard simply speaks some words (wiggling fingers optional) and POOF! Lo and behold! Something materialize / dematerialize / turns into a frog.

I do not doubt that Jack Vance is a great writer and his prose is beautiful but this book is not my bag. I remember reading the first

Lyonesse book and liking it so I think I will reread that instead of trying any more Dying Earth books. I respect The Dying Earth, but we are just not meant to be together. -

So this consists of 6 Sci-Fi short stories, and they are interconnected in some way. After reading this, all I can conclude is that I'm not fond of anthologies. Some stories are good, but some are also bad, and that makes the over-all rating low.

I liked the first 2 stories of The Dying Earth. Both were very interesting and I read them very quickly. The third one, started to falter off. The 4th and 5th were mildly interesting, but the last one was completely unbearable. The plot of the last one was not enjoyable in any way, even the main character was boring.

The whole anthology didn't consist of the typical Sci-Fi war, political drama, technological advancement and some other usual stuff. It basically consisted of characters and their lives. When I was looking for a good Sci-Fi book, this book caught my interest. It in no way satisfied my wanting to read a good Sci-fi novel though. I'm going to try and stay away from anthologies from now on, cause I haven't had a good experience with one. -

First off, I strongly recommend Aerin's review, since it's her review that lead me to the book. For me, briefly, I pretty much knew, within about 50 pages or so, that Dying Earth was special. You can read oceans of speculative fiction, enjoying a great deal of it, but it's only on occasion that you run across something that strikes you as Original, that exists beyond the time in which it was written. (I would probably liken this reading experience (espicially so with Vance's use of "high language") with the one I had reading Eddison's The Worm Ouroboros.) The Dying Earth is one of those books. DE is really a loosely connected short story collection. Going into it, I had some vague idea that Vance was a Hard Sci-Fi writer (I have no idea where that came from -- the misleading cover art?). Not so. More like a mix of science and magic. I definitely picked up on some Clark Ashton Smith vibes, but without the purple prose. But also L. Frank Baum (you'll see). Strictly speaking, this is Fantasy-Sci Fi, but with a strong nod toward Horror (I think Aerin mentions this as well). For example, I would have no trouble slotting "Liane the Wayfarer" in a Horror anthology (a good one). If you like Lovecraft, you'll like "Liane." ("Chun the Unavoidable" is, for me, however brief his appearance, up there with great Nasties of Literature.) I did have some problems with the last (and longest) story, "Guyal of Sfere." I had trouble following the flow of action at the end. But there's a lot to like about the story as well, and the problems could of been rooted in a distracted reading on my part. I would certainly be willing to give it another go, and I left the book as a whole wanting to read more of Vance.

-

Οι πρώτες τρεις ιστορίες (Ο Τουργιάν του Μίρ, Ο μάγος Μαζιρίαν και Τ'σαις) μ'άρεσαν πολύ αντίθετα τις επόμενες τις βρήκα πολύ αδιάφορες....

-

3.5

-

Unbelievable. I read Jack Vance's '"The Star King" and thought I had hit gold. Now I read this and find it even better. This novel is so much fun, I can't stand it. Terrific writing and as imaginative as I think it is possible to get. My only complaint is that it was so short that I was left wanting much more. Completely amazing.

-

The Dying Earth is the first volume in Jack Vance's eponymous fantasy series. It is a series of loosely connected adult fairy tales, set in a far-future vision of earth.

The setting for The Dying Earth features our sun, Sol, in its red giant phase. I have read that our sun will become a red giant in 5 billion years, so I'm using that as a timetable since a better one is not mentioned in the book. Perhaps the people of future Earth have more advanced science and magic, but my understanding is that the increased heat from hydrogen shell burning would incinerate all life on Earth before Sol becomes a red giant. Even if we somehow survive that, the outer layers of the expanding red giant would consume Earth before it "burned out" and became a planetary nebula. This "burning out" seems to be the event inhabitants of The Dying Earth fear, perhaps in error? In any event, I was able to convince my brain to at least agree with Vance that a future solar event will likely render Earth uninhabitable if, in fact, it is still habitable when that occurs. Vance's far-future earth has seen the rise and fall of countless civilizations, the ruins of which are scattered about in various states of decay, leaving a wide range of increasingly incomprehensible technology for the devolving Dying Earthlings to puzzle over. This is a deft literary device, as it allows Vance to invent any sort of technology, mostly as plausible as his solar predictions, but interesting nonetheless. Alongside these strange technologies, magic has at some unspecified point become functional, and a few magically endowed Dying Earthlings are able to cast such wondrous spells as "The Excellent Prismatic Spray", which causes beams of light to impale the target, and "The Charm of Untiring Nourishment" which makes food, water, and air unnecessary to the caster for a short time. As a whole, I found the setting to be much more imaginative than those in some modern science fiction and fantasy books I've read. The Dying Earth strongly appealed to my love of original science fiction/fantasy mash-ups, and I can't wait to read more about it in the next book "The Eyes of the Overworld."

Vance's writing is very poetic, ornate, and formal, adding to the alien nature of this future world. Interactions that might sound, to some, like William Shakespeare negotiating a trade agreement might amount to a declaration of undying love on The Dying Earth. Poetic writing in sci-fi and fantasy does not seem to be very popular currently, but I enjoy and appreciate Vance's voice. In addition to using words not common in today's vernacular, Vance also liked to mix in those of his own invention with no further explanation. It's generally pretty easy to understand what these fictional words are describing on the fly, and it oddly enhanced my reading experience even more.

Most of the characters in the book are imperfect, even what one might describe as "bad people". Murderous rogues, slavers, magicians who enjoy imprisoning and torturing people, magicians who create humans in vats, and cannibals are the types you might expect to meet on The Dying Earth. This creates a danger-filled, adventurous atmosphere where anything and everything goes. Interactions between them are very opportunistic and cynical, which helps to reinforce the setting, reminding me of Conan and Kull stories. "Between the time when the oceans drank Atlantis and the rise of the sons of Aryas, there was an age undreamed of. And unto this, Conan, destined to wear the jeweled crown of Aquilonia upon a troubled brow. It is I, his chronicler, who alone can tell thee of his saga. Let me tell you of the days of high adventure!"

I highly recommend The Dying Earth to anyone who enjoys aging sci-fi and fantasy. Also to anyone who plays Dungeons and Dragons, and would like to experience one of the major influences on its original designers. I listened to the audiobook narrated by Arthur Morey, and it made for an excellent series of bedtime stories.

This review is also posted on my blog, Hidden Gems. -

Въпреки изключително малкото преведени на български негови книги, Джек Ванс успя да ми стане един от любимите класически автори на фантастика. С пълпи сюжетите си се нарежда в сърцето ми до съвремениците си ван Воггт и Мерит.

„Залезът на земята” е първа книга от четирите в поредицата и единствената, която е видяла издаване у нас.

Шест бегло свързани истории за една дива и уморена земя, под едно угасващо слънце, чиито останали малко жители са деградирали до задоволяване на първични животински импулси, а науката отдавна се смята за магия, която също постепенно изпада в забрава. Под червеното слънце ходят учени(магьосници), клонинги(плод на магия) и генномодифицирани чудовища. Злото е „дестилирано” в окаяните остатъци на човечеството и озлобената от манипулациите му природа, всеки гледа собственото си мизерно оцеляване и болни амбиции.

Светът е обстоятелствено описан с една мрачна красота, успявайки да открадне вниманието на читателя от не дотам оригиналните сюжети и да вкара книгата в това, което критиците наричат пурпурна проза (Стил, който някой родни автори те първа преоткриват и засират с напудрените си опити).

Вдъхновила редица писатели, художници и творци от други поприща, „Залезът на земята”

заслужава да се прочете от всеки фен на магичното и фантастичното, както и от всеки автор тръгнал да твори в тези селения. -

Under the deep red sun of a far, far future wizards and sorcerers, sorceresses and creatures, blends of animal and plants, creatures un-thought of wander across an Earth in ruins where pockets of people still live, awaiting the end when the sun goes out.

Sounds dramatic doesn't it? This is considered a classic of it's kind and has been built on since. I found it mildly interesting over all but to be honest by the end I really didn't care much anymore. The blush was off the rose so to speak. From humans grown in vats to a quest that leads to the Museum containing mans history and knowledge the stories flow into a whole. It just failed to hold my interest. Maybe I'm jaded?

I know some love these/this stories/story and if you're one then I suppose you've found a gem. Enjoy it and if you want, all the follow-ups. I think (personally) that Vance has done much better work and don't plan to revisit the Museum of the Dying Earth. To each his own as they say. Not a bad read, but not great, see what you think. -

I've read a short story in this series & it was OK. I think it was in one of the early "Flashing Swords" anthologies. I don't care for the style of writing. The world is certainly imaginative, but too chaotic & there is no real characterization. Also there are too many weird names to keep track of in the bits & pieces I listen to. Nope, just not going to work for a whole book. Moving on.

-

Vance's Prismatic Charm of Beautiful, Untiring Adventure

Review Summary:

The Dying Earth, is beautiful, pulpy adventure. It is a series of six connected short tales (chapters), each being a mix of (Sword & Sorcery) and (Sword and Planet)...so consider it (Sword & Sorcery & Planet). And, it is an important classic, first published in 1950; Jack Vance's codification of magic items & spells proved influential in RPG-game design.

Dying Earth Series:

Tales of the Dying Earth: The Dying Earth/The Eyes of the Overworld/Cugel's Saga/Rhialto the Marvellous is an omnibus edition of the four novels written by Jack Vance (1916-2013) between 1950 and 1986; the first is simply

The Dying Earth, which is itself a collection of six short stories.

With the recent passing of

Jack Vance (1916-2013), the Sword and Sorcery Group is reflecting on his work this Summer (July-August):

The Dying Earth (1950) is the first in the series (the next three in sequence are: (2)

The Eyes of the Overworld (1966), (3)

Cugel's Saga (1983), (4)

Rhialto The Marvellous (1984)).

Codifying Magic - Role Playing Game (RPG)s: Tolkien maybe credited for inspiring "fellowships" of Dwarves, Elves, and Humans to go adventuring (a key trope for RPGs), but his magic-system was never codified well. Some ontology, or approach to classifying, was also needed ...and already provided, actually. Before "Lord of The Rings", Vance delivered The Dying Earth, and seems responsible for providing RPG-franchises with the needed approach: captivating brand names. Vance's Items and Spell titles simply exhibit self-evident credibility : Magic Items such as Expansible Egg, Scintillant Dagger, and Live Boots...and Spells such as Excellent Prismatic Spray, Phandaal's Mantle of Stealth, Call to the Violent Cloud, Charm of Untiring Nourishment. Three decades after The Dying Earth was published, the broader fantasy culture apparently caught on to the branding of spells and magic items (i.e. 1980's Dungeons & Dragons… or even magic-based card games like Pokemon, etc.).

Pace & Style: The title evokes gloomy adventure. The stories follow suit. The poetic, weird narratives will remind readers of predecessor

Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961)'s

Lost Worlds; the swashbuckling adventure and planetary exploration evoke Vance's contemporary

Roger Zelazny (1936-1995)'s

The First Chronicles of Amber. Each tale moves at breakneck speed. Often times, within just one page, teleportation will propel the protagonist across multiple planetary systems and vast continents. Actually, the pace is too fast and the stories appear rushed (keeping this from receiving a 5-star rating). Most encounters involve some haggling/negotiating, and some of these lead to sudden brutality:"Then you may die." And Mazirian caused the creature to revolve at ever greater speeds, faster and faster, until there was only a blur. A strangled wailing came and presently the Deodand's frame parted. The head shot like a bullet far down the glade; arms, legs, viscera flew in a direction." -- Ch2- Mazirian the Magician

The brisk pace belies the serious, philosophical undertones that persist throughout. The milieu does involve the decline of earth, after all, but Vance does not dwell on it. The action is at the forefront, but darkness is continuously dosed. One moment he'll be describing some present urgency, and then he will sneak in a bit of epic, chronic darkness:"At one famous slaughtering, Golickan Kodek the Conqueror had herded here the populations of two great cities, G'Vasan and Bautiku, constricted them in a circle three miles across, gradually pushed them tighter and tighter, panicked them toward the center within his flapping-armed sub-human cavalry, until at last he had achieved a gigantic, squirming mound, half a thousand feet high, a pyramid of screaming flesh."-- Ch2- Mazirian the Magician

Beauty Theme: The tales share many of the same characters, but each has a different protagonist. The protagonist from the six tale (Guyal) seems to speaks on behalf of the author's muses; he invites readers to consider:"Where does beauty vanish when it goes?"

Guyal's Father Answers: "Beauty is a luster which love bestows to guile the eye. Therefore it may be said that only when the brain is without love will the eye look and see no beauty." - Story 6- Guyal of Sfere

Vance's work seems genuinely motivated by an appreciation of art and the mourning of lost beauty. He seemed to be following in succession from like-authors.

Mary Shelley,

Edgar Allen Poe,

Clark Ashton Smith,

H.P. Lovecraft all delved into evoking emotions through their art; they were serious writers who philosophized and wrote essays regarding "Weird Beauty" in literature.

The undercurrents of dark muses in literary horror fascinate some (link). Below are excerpts and comments of Beauty's themes in The Dying Earth (per story):

1) Turjan of Mirr: The books opens with a sorcerer trying to create living things. His craft, his art, is "life." He mirrors the plight of Victor

Frankenstein:"[Turjan] considered its many precursors: the thing all eyes, the boneless creature with the pulsing surface of its brain exposed, the beautiful female body whose intestines trailed out into the nutrient solution like seeking fibrils, the inverted inside-out creatures...Turjan sighed bleakly. His methods were at fault; a fundamental element was lacking from his synthesis, a matrix ordering the components of the pattern."

"For some time I have been striving to create humanity in my vats. Yet always I fail, from ignorance of the agent that binds and orders patterns."

"This is no science, this is an art, where equations fall to the elements like resolving chords, and where always prevails a symmetry either explicit or multiplex, but always of a crystalline serenity."

Turjan needed more knowledge to complete his goal. This compels him toward making a woman who appreciates beauty (to compete with another woman who cannot detect beauty).

2) Mazirian the Magician: This chapter has significant overtones of Clark Ashton Smith's Maze of Maal Dweeb, Xiccarph tales (1935, 1930)...in which an alien sorcerer had the "caprice to eternalize the frail beauty of women," maintaining them in a garden. Here, the beautiful T'sain dies to save her maker, Turjan, in a magic-filled chase through an alien sorcerer's garden. This excerpt demonstrates how Vance never ceases to pour out the colors!"Certain plants swam with changing iridescences; others held up blooms pulsing like sea-anemones, purple, green, lilac, pink, yellow. Here grew trees like feather parasols, trees with transparent trunks threaded with red and yellow veins, trees with foliage like metal foil, each leaf a different metal--copper, silver, blue tantalum, bronze, green iridium. Here blooms like bubbles tugged gently upward from glazed green leaves, there a shrub bore a thousand pipe-shaped blossoms, each whistling softly to make music of the ancient Earth, of the ruby-red sunlight, water seeping through black soil, the languid winds…"

3) T'sais: The titular character, once an antagonist piece-of-art, searches out the ability to see beauty on Earth. As she describes:"Pandelume created me," continues T'sais, "but there was a flaw in the pattern." And T'sais stared into the fire. "I see the world as a dismal place: all sounds to me are harsh, all living creatures vile, in varying degrees--things of sluggish movement and inward filth. During the first of my life I thought only to trample, crush, destroy. I knew nothing but hate. Then I met my sister T'sain, who is as I without the flaw. She told me of love and beauty and happiness--and I came to Earth seeking those."

Etarr, an ugly companion of T'sais who had his hansom face switched with a demon's, goes with her to witness a Black Sabbath. As they watch the demons congragate, Vance philosophizes:"Even here is beauty," he whispered. "Weird and grotesque, but a sight to enchant the mind."

4) Laine the Wayfarer : Laine the arrogant magician is challenged to repair a piece of art: Lith's tapestry. Therein is depicted the Magic Valley of Ariventa, but it has been cut in half. Can he restore it?

5) Ulan Dhor: This is a fun piece, with more sci-fi than the others given the reactivation of ruined technology. The artistic elements are less covert here. There are two embattled groups that literally cannot see another. They signify themselves not with classic blazonry...but by simply by color: Green vs. Grays (vs. Reds)!

6)Guyal of Sfere: Guyal's insatiable search for knowing everything leads him on a quest to speak to the Curator of humankind's knowledge. En route, he partakes as a judge in a beauty pageant; here he meets with the maiden Shierl. They go on to explore sacred ruins, battle a demon who consumes beauty, and look upon the treasure trove of beauty, a sanctuary:"This is the Museum," said Guyal in a rapt tone. "Here there is no danger...He who dwells in beauty of this sort may never be other than beneficent…"

All in all, a recommended read to any sci-fi and fantasy buff, and to any reader who also likes RPGs. Feel welcome to join the discussion (at any time...even if the official group-read time expires):

Group-Read Link. -

She rode deep in thought, and overhead the sky rippled and cross-rippled, like a vast expanse of windy water, in tremendous shadows from horizon to horizon. Light from above, worked and refracted, flooded the land with a thousand colors, and thus, as T'sais rode, first a green beam flashed on her, then ultramarine, and topaz and ruby red, and the landscape changed in similar tintings and subtlety.

T'sais closed her eyes to the shifting lights. They rasped her nerves, confused her vision. The red glared, the green stifled, the blues and purples hinted at mysteries beyond knowledge. It was as if the entire universe had been expressly designed with an eye to jarring her, provoking her to fury... A butterfly with wings patterned like a precious rug flitted by, and T'sais made to strike at it with her rapier. She restrained herself with great effort; for T'sais was of a passionate nature and not given to restraint. She looked down at the flowers below her horse's feet-pale daisies, blue-bells, Judas-creeper, orange sunbursts. No more would she stamp them to pulp, rend them from their roots. It had been suggested to her that the flaw lay not in the universe but in herself. Swallowing her vast enmity toward the butterfly and the flowers and the changing lights of the sky, she continued across the meadow.

A bank of dark trees rose above her, and beyond were clumps of rushes and the gleam of water, all changing in hue as the light changed in the sky. She turned and followed the river bank to the long low manse. She dismounted, walked slowly to the door of black smoky wood, which bore the image of a sardonic face. She pulled at the tongue and inside a bell tolled.

There was no reply.

"Pandelume!" she called.

Presently there was a muffled answer: "Enter."

She pushed open the door and came into a high-ceilinged room, bare except for a padded settee, a dim tapestry.

"What is your wish?" The voice, mellow and of an illimitable melancholy, came from beyond the wall.

"Pandelume, today I have learned that killing is evil, and further that my eyes trick me, and that beauty is where I see only harsh light and evil forms."

For a period Pandelume maintained a silence; then the muffled voice came, replying to the implicit plea for knowledge.