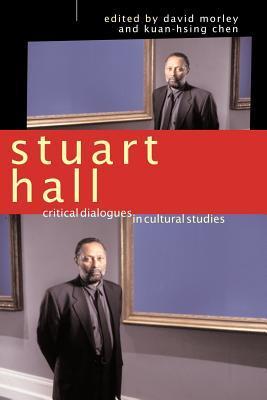

| Title | : | Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0415088046 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780415088046 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 522 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1996 |

In addition to presenting classic writings by Hall and new interviews with Hall in dialogue with Kuan-Hsing Chen, the collection, which includes work by Angela McRobbie, Kobena Mercer, John Fiske, Charlotte Brunsdon, Ien Ang and Isaac Julien, provides a detailed analysis of Hall's work and his contribution to the development of cultural studies by leading cultural critics and cultural practitioners. The book also includes a comprehensive bibliography of

Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies Reviews

-

At the start of the year I had to do my ‘exit’ presentation at Summer School for PhD students. It’s a requirement that you do some sort of presentation on your research and I thought I would get it over with – not because I was all that close to ‘exiting’, although I should finish soon-ish, I hope. Anyway, there was an academic in the audience and he said a couple of things that got under my skin. The first was that my results were mostly banal. Always nice to know, obviously. Not that I mind all that much, generally when people decide they want to insult me they say my ideas are naïve, so, banal is, at least, a step in the right direction. The other thing he said was that my focus on ‘false consciousness’ made my research look like a 1970s Marxist exercise of banality. I’ve never really read any of the 1970s Marxists and am not sure what to think about the idea of ‘false consciousness’. So, it seemed time to do some reading. The first thing I thought I should do was read some Marx – which had me reading Capital. But I’ve been thinking about the whole idea of ‘false consciousness’ for much of the year in one way or another. Reading this book has been an important part of that ‘thinking’.

The first chapter of this – after the introduction which is particularly good – is Hall’s ‘Marxism Without Guarantees’. The idea being that most versions of Marxism do come with guarantees. That is, historical inevitability is a big part of what Marxism is about. The class struggle inevitably leads in one direction, with society increasingly dominated by the struggle between the two great classes of our age, the working and capitalist classes – and inevitably this struggle can only end in one way – with the working class taking over the means of production and drawing smiley faces everywhere. The problem is that Marx predicted this particular ‘and they all lived happily ever after’ quite some time ago and, well, for something that is inevitable it seems to be dragging its feet a bit.

By the 1970s even Marxists had begun to notice. I’m not criticising – Christians have been waiting 2000 years for the imminent return of Jesus, so, all things considered and putting it all in it’s proper perspective and what-not…

One way to explain the delay of the socialist revolution is to say that the workers have ‘false consciousness’. That is, that they have confused their own self-interest with that of the ruling class and that they therefore end up doing things, believing things and supporting parties that are actually directly opposed to their own interests. Hard to argue with this, in a sense. The way that people in the US get very upset about Obama Care, even people without any other health insurance in a land that will let you die in the street if you have no health insurance is a fairly graphic example, but hardly the only one that springs to mind.

The problem here is that there are sort of two strands to Marxism – often associated with the early and the late Marx. So that when Marx was young he got together with Engels and wrote the German Ideology. In this he argued that the ruling ideas of any age were the ideas of the ruling class. And therefore, the ruling class sought to impose their own ways of seeing the world on everyone else in society and particularly undermined those ideas that might seek to take away some of their power. The later Marx was less interested in ideas as such, preferring to stress that how the economic base that society rests on is organised directly structures how society thinks about the world. Changes in the economic base cause changes in how people think in society and, eventually, these changes will lead to socialism through the increasingly social nature of the production process itself.

Run too far with either of these ideas and it seems that you could pretty quickly end up with two quite different kinds of Marxism – a situation not made any easier by perhaps one of the most famous quotes from Marx himself being that he once said, effectively, 'well, if that is what it is to be a Marxist then I am not a Marxist.

The other person you probably need to know is Gramsci. An Italian Marxist, and so being Italian he was interested in culture rather than straight economic determinism. Gramsci is mostly associated with the word ‘hegemony’. Which is sort of a strong version of the German Ideology idea of ruling ideas and ruling classes. That is, that not only do ruling classes stuff their ideas down everyone’s throats, but they don’t necessarily know that is what they are doing, they see their ideas as just common sense and if you don’t agree with common sense, then, well, you must be nuts and society needs to be protected from you. I like this, as I don’t particularly like ‘conspiracy’ theories and I tend to think that although people can be pretty well relied upon to act according to their own self-interest, people also like to think well of themselves, and so they need to believe they are not just acting as selfish bastards, but that they fundamentally deserve their place in the world. This works for both the rich and the poor – and therefore the whole ‘false consciousness’ stuff discussed above.

Hall invented (well, sort of) Cultural Studies – and Cultural Studies is clearly going to be focused, given its roots are at least in ground close to where Marxism grows, on how people think the things that they do.

Much of this book is just that – a working out of these questions in relation to how much economics structures (or whatever it does) our ideas, how much race influences culture, is feminism more or less important than the ‘class struggle’, and what about queer rights, environmentalism and so on?

I want to say something about that, but want to say this first. This book is really interesting in how it is structured. In fact, I’m not sure I’ve really read a book structured in quite the same way. Hall generally has an article or two at the start of each section, but then some other theorist, often quite famous, will also have an article and their article is often quite critical of Hall’s one. It got to the stage where I started thinking – surely someone must have something nice to say about poor old Hall. But, of course, they did. And in some ways this is the most respect you can offer someone – not unquestioning loyalty, but deep engagement with what they are saying and even giving some of their ideas a bit of a kick. Still, this means that you do have to have your wits about you when you read this book. This isn’t an exercise in pure deconstruction for its own sake, the theorists here are all seeking something important, an understanding of the role of culture in society, but this is a hard problem and there are lots of ways of looking at this problem and all of them shine lights back into your eyes that can both dazzle and confuse.

Right, the bit I wanted to say is about the Marxist idea that the class struggle is the foundational struggle in society and that other struggles: feminist, anti-racist, gay rights and so on – are all secondary and therefore are probably only likely to be solved once the class struggle is fixed. I want to say that the idea I’m coming to is that this is both not a terribly useful idea and one that misses something very important about these other struggles, particularly in relation to the idea of ‘false consciousness’. For the last couple of years I’ve been reading stuff about racism. I live in Australia, racism is becoming increasingly central to understanding life here. Now, the first thing to know is that scientifically ‘race’ isn’t actually a ‘thing’ – as young people like to say. The genetic differences between ethnic groups certainly exist – black skin, curly hair, blue eyes, all these things exist and are genetic. However, these differences are strikingly superficial. And as the Nazis discovered, remarkably hard to pin down. A book I read on blondes quotes some German guy who said, during the war, that, of course, Hitler was a blonde. It seems that if all of humanity was wiped out and there was just one tribe left, virtually all of human diversity would remain intact. The problem is that racism isn’t based on any of this shit – and I don’t think any of us really believe scientists when they tell us this stuff on some levels. The differences appear to us as obvious and the counter stories from science sound a bit like the ‘oh yeah, Hitler is a blonde’ idea. It goes against our ‘common sense’. The problem is that we already know stuff, based on our ‘experience’ and all of this smells very much like the 1970s idea of false consciousness.

The person to read on a lot of this stuff is bell hooks – Black Looks is as good a place to start as any – but you can also read bell hooks on women too, or on class – she is multitalented. These ideas are interrelated and interpenetrating. But more than this, they all define one group as superior and one as inferior and these ideas themselves are not just held by those who are superior, but also believed on many levels by those who are constructed as inferior. These ideas structure exactly how people come to understand the world – they are hegemonic in the sense that these ideas both support the existing structures in society, but do so by seeking to appear completely natural. So that, those who are trying to assert their own rights often have to do so by appearing to go against not only natural law, but rationality itself.

There is an awful lot to this book. One of the ideas I really wanted to talk about was the idea of articulation – it is discussed at length in the chapter following Hall’s Marxism without Guarantees. The idea being that the ‘facts’ of the world aren’t necessarily ‘ideological’, but that what makes them ideological is how they get joined up by a narrative – this articulation is key and therefore something that people need to learn to notice – which is part of the role of cultural studies. I think this is a nice way to understand this problem. Like I said, there is much more here than I can really cover – but, if you are going to read this, I really do think it would be a very good idea to read the second-last chapter first. This is an interview with Hall and covers a lot of his life and work and why he did things he did and how different bits fit together. It is one of those things about books like this, you can always make an argument for putting one thing in front of another, but I really could feel certain pennies dropping while I read this chapter and did think it would have made other parts of the book easier to understand if I’d read it first. -

Stuart Hall died as I was in the middle of reading this, which made it so poignant even as I was thinking to myself just how good this book was as a totality and how much I loved him. Like many edited collections it had pieces that I loved and pieces that I didn’t, but even those that I didn’t find so useful still worked brilliantly to give me a solid sense of the international field of Cultural Studies from its early beginnings through the 1990s. That’s no small task given the way that it has changed and spread, been fought over and fought through. I’m not sure where it’s at now, but I feel that I know some of the places it has been and the structures of its debates.

I confess now, that Stuart Hall is one of my favourite theorists, and though I know the field is far greater and wider than him, it is his work that I feel opens up the most space for my own thinking in political geography. The first section looks at Marxism and cultural studies, and given my own relationship to Marxism is much like Hall’s, I wanted this section to be longer and I wanted more on the New Left. The authors are definitely more interested in the relationship between Cultural Studies and postmodernism, so I got more postmodernism than I wished but that was all to the good perhaps, as I discovered some redeeming characteristics…though not too many.

After a good intro from the editors it start with ‘The Problem of Ideology: Marxism Without Guarantees’.The problem of ideology, therefore, concerns the ways in which ideas of different kinds grip the minds of the masses, and thereby become a ‘material force’. In this, more politicized, perspective, the theory of ideology helps us to analyse how a particular set of ideas comes to dominate the social thinking of a historical bloc, in Gramsci’s sense; and, thus, helps to unite such a bloc from the inside, and maintain its dominance and leadership over society as a whole. It has especially to do with the concepts and the languages of practical thought which stabilize a particular form of power and domination….

We mean the practical as well as the theoretical knowledges which enable people to ‘figure out’ society, and within whose categories and discourse we ‘live out’ and ‘experience’ our objective positioning in social relations. (27)

This is a revision of Marx’s model of ideology which ‘did not conceptualize the social formation as a determinate complex formation, composed of different practices, but as a simple structure’ (29), this via Althusser. And I’ve always loved his take on traditional arguments about ‘false consciousness’Is the worker who lives his or her relation to the circuits of capitalist production exclusively through the categories of a ‘fair price’ and a ‘fair wage’, in ‘false consciousness’? Yes, if by that we mean there is something about her situation which she cannot grasp with the categories she is using; something about the process as a whole which is systematically hidden because the available concepts only give her a graso of one of its many-sided moments. No, if by that we mean she is utterly deluded about what goes on under Capitalism.

The falseness therefore arises, not from the fact that the market is an illusion, a trick, a sleioght-of-hand, but only in the sense that it is an inadequate explanation of a process (37).The relations in which people exist are the ‘rela relations’ which the categories and concepts they use help them to grasp and articulate in thought. But—and here we maybe be on a route contrary to emphasis from that with which ‘materialism’ is usually associated—the economic relations themselves cannot prescribe a single, fixed and unalterable way of conceptualizing it…. To say that a theoretical discourse allows us to grasp a concrete relation ‘in thought’ adequately means that the discourse provides us with a more complete grasp of all the different relations of which that relation is composed, and of the many determinations which forms its conditions of existence. In means that our grasp is concrete and whole, rather than a thin, one-sided abstraction (39).

And then he draws on Volsinov, who I truly love, to argueIt is precisely because language, the medium of thought and ideological calculation, is ‘multi-accentual’…that the field of the ideological is always a field of ‘intersecting accents’ 40

And thus a source of struggle, every word contested terrain. Which he repeats: ‘This approach replaces the notion of fixed ideological meanings and class-ascribed ideologies with the concepts of ideological terrains of struggle and the task of ideological transformation’ (41). Then draws on Gramsci to see how these ideologies become material forces by articulating with political and social forces to deconstruct and reconstruct the ruling ideologies in a ‘war of position’. The terrain of this struggle is historically defined, above all it is the terrain of common sense, which become the stakes of ideological struggle. Thus ‘‘hegemony’ in Gramsci’s sense requires, not the simple escalation of a whole class to power, with its fully formed ‘philosophy’, but (43) the process by which a historical bloc of social forces is constructed and the ascendency of that bloc secured’. In thinking about the relationship between base and superstructure:What the economic cannot do is (a) to provide the contents of the particular thoughts of particular social classes or groups at any specific time; or (b) to fix or guarantee for all time which ideas will be made use of by which classes. The determinacy of the economic for the ideological can, therefore, be only in terms of the former setting the limits for defining the terrain for operations, establishing ‘raw materials’, of thought. Material circumstances are the net of constraints, the ‘conditions of existence’ for practical thought and calculation about society.

And a smack down against orthodoxy and ‘determination in the last instance’:‘It represents the end of the process of theorizing, of the development and refinement of new concepts and explanations which, alone, is the sign of a living body of thought, capable still of engaging and grasping something of the truth about new historical realities (45).

One of the more useful chapters was from Colin Sparks, outlining the work of Raymond Williams and EP Thompson and cultural studies’ beginnings in a humanist Marxism before its encounter with Althusser and Marxism, its engagement with Laclau and Gramsci. It does through multiple representatives of the school, not just Hall, which I particularly liked.

My favourite, apart from Hall’s own work, was ‘The Theory and method of articulation in cultural studies’ by Jennifer Daryl Slack. She writesHowever, articulation works at additional levels: at the levels of the epistemological, the political and the strategic. Epistemologically, articulation is a way of thinking the structures of what we know as a play of correspondences, non-correspondences and contradictions, as fragments in the constitution of what we take to be unities. Politically, articulation is a way of foregrounding the structure and play of power that entail in relations of dominance and subordination. Strategically, articulation provides a mechanism for shaping intervention within a particular formation, conjuncture or context (112).

And also this:cultural studies works with the notion of theory as a ‘detour’ to help ground our engagement with what newly confronts us and to let that engagement provide the ground for retheorizing. Theory is thus a practice in a double sense: it is a formal conceptual tool as well as a practising or ‘trying out’ of a way of theorizing’ (113).

Conceptualisations of theory as process, as being constantly regrounded and rethought, are the only ones that make sense to me. Of course, I feel that if you are grounded you are working under the assumption that we live in a profoundly unequal and exploitative society and that theory is meant to change that, so I do have some parameters.With and through articulation, we engage the concrete in order to change it, that is, to rearticulate it…Articulation is, then, not just a thing (not just a connection) but a process of creating connections, much in the same way that hegemony is not domination but the process of creating and maintaining consensus or co-ordinating interests’ (114).

Lawrence Grossberg’s interview with Hall on Postmodernism helped a great deal in clarifying some of my own thoughts. Like Hall on Foucault:let’s take Foucault’s argument for the discursive as against the ideological. What Foucault would talk about is the setting in place, through the institutionalization of a discursive regime, of a number of competing regimes of truth and, within these regimes, the operation of power through the practices he calls normalization, regulation and surveillance. … the combination of regime of truth plus normalization/regulation/surveillance is not all that far from the notions of dominance in ideology that I’m trying to work with…I think the movement from that old base/superstructure paradigm into the domain of the discursive is a very positive one. But, while I have learned a great deal from Foucault in this sense about the relation between knowledge and power, I don’t see how you can retain the notion of ‘resistance’, as he does, without facing questions about the constitution of dominance in ideology. Foucault’s evasion of this question is at the heart of his proto-anarchist position precisely because his resistance must be summoned up from nowhere… there is no way of conceptualizing the balance of power between different regimes of truth without society conceptualized (135) not as a unity, but as a ‘formation’. If Foucault is to prevent the regime of truth from collapsing into a synonym for the dominant ideology, he has to recognize that there are different regimes of truth in the social formation. And these are not simply ‘plural’ – they define an ideological field of force (136).

And on Baudrillard (and others, but mostly Baudrillard)I don’t think history is finished and the assertion that it is, which lies at the heart of postmodernism, betrays the inexcusable ethnocentrism—the Eurocentrism—of its high priests. It is their cultural dominance, in the West, across the globe, which is historically at an end…I think Baudrillard needs to join the masses for a while, to be silent for two-thirds of a century, just to see what it feels like (141).

Now, more to the point, his own theory of articulationthe theory of articulation asks how an ideology discovers its subject rather than how the subject thinks the necessary and inevitable thoughts which belong to it; it enables us to think how an ideology empowers people, enabling them to begin to make some sense or intelligibility of their historical situation, without reducing those forms of intelligibility to their socio-economic or class location or social position (142)

And thisI am not interested in Theory. I am interested in going on theorizing. And that also means that cultural studies has to be open to external influences, for example, to the rise of new social movements… (150)

I can’t do justice to such a sprawling volume full of brilliant contributors, so I am focusing on this concept of articulation that I am grappling with right now…but there is are lovely interventions from Angela Robbie and Charlotte Brundson over the struggle of women to gain power and voice in the New Times Project. It is both political but also personal, and to me these kinds of articles are so important for those of us without those historical memories about just how hard women have had to struggle even in left departments, and the forms this struggle took.

More from Hall on ‘Cultural studies and its theoretical legacies’, in reference to Homi Bhabba:I don’t understand a practice which aims to make a difference in the world which doesn’t have some points of difference or distinction which it has to stake out, which really matter. It is a question of positionalities (264).

And back to my own relationship with theory really:I want to suggest a different metaphor for theoretical work: the metaphor of struggle, of wrestling with the angels. The only theory worth having is that which you have to fight off, not that which you speak with profound fluency (265)

How can you not love someone who writes of his study of Althusser ‘I warred with him, to the death’ (266).

I loved David Morley’s article ‘EurAm, modernity, reason and alterity’ for its discussion of centres and peripheries (though I wish people unpacked the US just a little more, with its white culture one of the centre, but containing within it the colonized, the enslaved, the murdered), its review of post-colonial thought and brilliant quotes from people who are now on my list of things to read.

I’ll end with Hall’s ‘Gramsci’s relevance for the study of race and ethnicity’. First, a return to defining Hegemony1. ‘hegemony’ is a very particular, historically specific, and temporary ‘moment’ in the life of a society…They have to be actively constructed and positively maintained.

2. we must take note of the multi-dimensional, multi-arena character of hegemony. It cannot be constructed or sustained on one front of struggle alone (for example, the economic). It represents a degree of mastery over a whole series of different ‘positions’ at once. Mastery is not simply imposed or dominative in character. Effectively, it results from winning a substantial degree of popular consent.

3. What ‘leads’ in a period of hegemony is no longer described as a ‘ruling class’ in the traditional language, but a historic bloc. (424)

And of course, the two kinds of struggle, ‘war of manoeuvre’ ‘where everything is condensed into one front and one moment of struggle’, and the ‘war of position’, ‘which has to be conducted in a protracted way, across many different and varying fronts of struggle’ (426).

It’s interesting putting this solid description in conjunction with Lawrence Grossberg’s description in an earlier piece ‘History, politics and postmodernism’Hegemony is not a universally present struggle; it is a conjunctural politics opened up by the conditions of advanced capitalism, mass communication and culture. Nor is it limited to the ideological struggle of the ruling class bloc to win the consent of the masses to its definition of reality, although it encompasses the processes by which such a consensus might be achieved. But it also depends upon the ability of the ruling bloc (an alliance of class fractions) to secure its economic domination and establish its political power. Hegemony need not depend upon consensus nor consent to particular ideological constructions. It is a matter of containment rather than compulsion or even incorporation. Hegemony defines the limits within which we can struggle, the field of ‘common sense’ or ‘popular consciousness’ (162)

Hall does more to open up the concept to see where counter-hegemony can come from:Ideas…’have a center of formation, of irradiation, of dissemination, of persuasion…’(PN, 192). Nor are they ‘spontaneously born’ in each individual brain. They are not psychologistic or moralistic in character ‘but structural and epistemological’. They are sustained and transformed in their materiality within the institutions of civil society and the state. Consequently, ideologies are not transformed or changed by replacing one, whole, already formed, conception of the world with another, so much as by ‘renovating and making critical an already existing activity’ (434).

I like also hegemony as not a ‘moment of simple unity, but as a process of unification (never totally achieved), founded on strategic alliances between different sectors, not on their pre-given identity’ (437).

Anyway. Much to think

-

a doozy

-

In my opinion Stuart Hall is the premiere English Cultural Theorist in the last thirty years, and his work is amazingly accessible. I've used his work to teach undergraduates about cultural theory and they ate it up! To think that in England intellectuals are respected to the point where Hall actually hosted the British version of Politically Incorrect. Take that Bill Maher!

-

Unfortunately I didn't have the pleasure of reading the whole book, only a couple of chapters for my sociology course. However, Stuart Hall writes about identity in such a way it is easy to understand even for those who are not interested in the field of sociology.

Very enlightening in terms of how it is in the UK and I look forward to reading the whole book at some stage. -

A collection of essays by and about the work of Hall, largely mapping the trajectory of cultural studies as a discipline, including its wrestling with issues of Marx, postmodernism, race, gender, and media studies. There are several gems, but together the book can be overwhelming and repetitive.

-

Fundamental book in the field of Cultural Studies