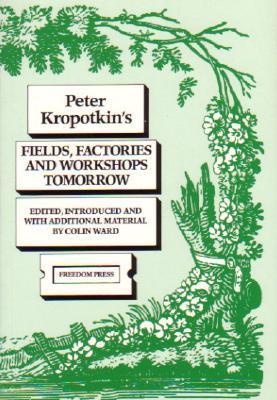

| Title | : | Fields, Factories and Workshops Tomorrow |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 090038428X |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780900384288 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 208 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1899 |

Fields, Factories and Workshops Tomorrow Reviews

-

The front end is loaded with now outdated statistics and observance about agriculture and production, but lays ground for the arguments made in the later chapters. Kropotkin diligently explains the irrationality of capitalist production, and how it could be much better utilised if it was instead focused around meeting community and human needs instead of producing profit for property owners.

The chapter on brain work and manual work is still *very* relevant today, as it makes a compelling case for breaking down the divisions of labour and giving children more practical and well rounded education (whilst still allowing people to pursue their own particular interests). The parts highlighting children viewing abstract geometry as a torture imposed on children by teachers, most of whom forget it two years after having to learn it through repetition rings true still.

While there are gaps and outdated statistics and areas where understanding can be expanded from today's point of view, it is still an important work in Kropotkin's contribution to anarchist theory as a way of imagining societies that are not based on class divisions and which can be fulfilling to our needs as human beings. -

Have a prized copy of this from 1913!

-

Cette lecture est la suite logique de la conquête du pain, qui apportais la prémisse et la vision de la méthodologie à suivre , et qui est mit en œuvre dans le présent ouvrage. À travers une analyse contextuelle exhaustive de la production industrielle et agricole de l’Europe du 19ieme siècle, kropotkine met en œuvre cette méthodologie. Mécanisation , technologie et collectivisation de la production pour le secteur agricole. Multiplications des petites et moyennes industries et atelier autogéré par les ouvriers pour produire les besoins matériels de base de chaque commune. Totale plaidoirie pour une souveraineté alimentaire et matérielle des peuples , par le peuple pour le peuple. Mais le plus important , une proposition de refonte complète du système d’éducation , qui ne divise plus la population en une classe ouvrière déconnecté du travail et de la connaissance intellectuel mais bien une union complète des 2 , à travers l’art et l’émancipation de l’individu humain complet. Seul bémol : la sacralisations de l’industrialisation et de la technologie à travers le paradigme de la domination de la nature , qui n’a plus sa place en 2021 par rapport à son empreinte écologique , sa destruction de l’environnement et sa vision anthropocentrique. J’ai adorer.

-

Unless you are researching Kropotkin do not read this book. Read the Conquest of Bread or Mutual Aid instead. Otherwise you’re just wasting your time. If you still want to read it, read the last chapter.

The book is dated, the view of the world is dated, but provides for an interesting history of agriculture and industry at the turn of 19th and 20th century in Europe.

Apart from that, nothing much… the thesis of combining “brain work and manual work” is lost and overshadowed by chapters upon chapters of statistics.

Also the ideas Kropotkin is advocating, well, ever heard of climate change? He obviously didn’t. -

Peter Kropotkin was of royal blood in 19th century Russia. Oddly enough, despite that, he was, ideologically, an anarchist. He wrote scientific works, such as Mutual Aid. He also wrote works trying to demonstrate how anarchism could work in practice. This is one such work. As an example, he shows how agriculture might be made more productive in England, Scotland, and elsewhere by adopting anarchist organizational principles. Will readers accept his perspective? Most probably will not, but his arguments are provocative. Similar arguments are raised with respect to manufacturing and so on.

If one wants to get a sense of Kropotkin's effort to be "relevant" in the late 19th and early 20th century, this would be a useful work to explore. . . . -

Lots of rather outdated figures throughout (though especially chapter 2), but chapters 4 and 5 finish the book well.

-

Some good stuff, but not enough time to finish it all.

-

the stuff about farming went a bit over my head, along with some stretches in some other chapters. don't skip over the editor's notes if your version has them.

-

The world needs more scientific socialism book like this one.

-

https://criticareflexivasituacion.wor... -

kitap eski olduğu için bazı yerler güncelliğini kaybedebiliyor, neyseki içinde editörün notu bölümleri güncel bilgilerle harmanlanıp bize sunuluyor.

-

What is the purpose of economy? In short, this is the fundamental question posed by the grandfather of anarcho-communism, Russian prince and occasional Santa Claus impersonator, Pyotr Kropotkin. The answer, in Kropotkin and many others socialists view, is the satisfaction of human needs, to secure a comfortable and secure life for all in accordance with the principle of ''from each according to his ability, to each according to his need''.

Written at the start of the 20th century, at the peak of industrialization of the Western world, of expansion of capitalism and its profit motive to all reaches of the globe, of a world divided and subdivided in economic functions of producers and consumers (divided even more in the daily labors of most people), of gross inequalities in terms of distribution of wealth and, despite the wealth accumulated by European states, a world still rife with poverty, suffering and destitution. A far cry from the common sense conclusion reached by Kropotkin and others. This book sets out to offer alternatives and fresh perspectives on approaches to agriculture, industry, science and education to reshape the economy into a an extension of social life, rather than a superimposed system under which resources trickle down a social pyramid.

A common theme in the book is the denunciation of a division of production and labor, weather it be states or regions specialized in the production of specific goods and mostly nothing else, or the separation of the main branches of economy, independent of each other to the methods of educating future workers both for mental and manual jobs. Throughout the book, Kropotkin echoes the need to integrate, rather to divide, and calls for autonomy and self-sufficiency, instead of a hyper-specialization that leaves nations open to the mercy of international politics and trade, with its specific speculators and fluctuations in fortunes.

The book makes use of large numbers of statistical data and observations, journals and sources from many fields and is followed by in depth and meticulous descriptions. They offer an insight into the amount of work put in to the writing of this book, not to mention, the amount of research dedicated to it, as well as Kropotkin's keen observational eye and enthusiasm and faith in a different, better world. However, some information relayed seems anecdotal or passed on from unreliable sources (at least by modern scientific standards) and for today's times the statistical data, unless one is an expert in early 20th century economic data, is antiquated, difficult to asses and cumbersome, often making for a very difficult read for a 21st century reader. For most of the book this is the case, making it a tough read that makes up for it in the concluding parts and with Kropotkin's dedication and enthusiasm.

Kropotkin offers a vision of a sustainable and self-sufficient humanity, who by the wits and hard work and progress of technology is unstoppable and relentless, in its ingenuity and desire to innovate and improve despite adverse situations. May it be the farmers of Guernsey or the textile craftsmen of France or the watchmakers of Jura in Swtizerland. Here, we find a side of humanity often forgotten, one of an autonomous and capable force that does not need a profit-motive, nor a hierarchical guiding hand, one were artistry and ingenuity do not require a prestigious education or appreciation of a select class, but rather, one that springs forth vibrantly and freely, given the chance and opportunity and unencumbered by oppressing forces. Its this free spirit, playful and spontaneous and boundless in its potentiality, that Kropotkin wishes to remind us of, and that economy is not a matter devoid of us, outside of to which we are subordinate, but rather, that WE are the economy, much as we are society and that it is only for our own common interest, that we should strive for. -

Britain had its Angry Brigade and its Class War Federation, but for the most part English anarchism seems to be of the more moderate, pragmatic variety, symbolized by people like Colin Ward. Could Kropotkin's long stay in England and later books like this one be partly responsible? Seems possible. Kropotkin's calm, quiet, almost boring optimism shines on every page. The central underlying idea seems to be that a radically better future is practically visible already and right around the corner. "And what prevents us from turning our backs to this present and from marching towards that future, or at least, making the first steps towards the future, is not the 'failure of science,' but first of all our crass cupidity - the cupidity of the man who killed the hen that was laying golden eggs - and then our laziness of mind - that mental cowardice so carefully nurtured in the past," he remarks in the Conclusion. If only that were all that prevented us! Such an attitude can be hard to swallow for anarchists today. But there's a lot to be gleaned from this book despite its simple faith.

The first priority of the revolution will be feeding itself. Kropotkin gives a lot of food for thought here - if you can stomach all the statistical detail and his detailed description of such things as the ins and outs of horticultural methods in Belgium in 1903 (You will learn a lot about the importance of loam and greenhouses). Today in the US, food politics are usually the province of liberals with no connection to struggles for social transformation. Nowadays lots of people are "locavores," fans of "slow food" and all things "artisanal" and "organic," heirloom products and sustainable agriculture, urban gardening - but often motivated by a kind of snobbish aesthetic appeal and backed up by deep pockets. If Kropotkin were alive today it seems he might encourage revolutionaries to reclaim these things as our own. His advocacy of small-scale, intensive, decentralized agriculture, more like a garden than a farm, near and inside cities as well, with great variety in each region sustaining itself by growing its own food, and participation by everyone, fits right in with today's reaction against the nightmare of agribusiness, factory farms, pollution, genetic manipulation, chemical fertilizers etc. When you connect the urge to take land and grow food for ourselves to an attack on capital, things get interesting. And Kropotkin's data and examples might be tiresome, but he demonstrates that even around 1900 such things were easily achievable.

Kropotkin essentially takes the themes of decentralization, appropriate scaling, and integration (of city and country, manual and intellectual labor, tasks and skills, crops and industries, etc.) and puts them at the center of his "political economy." His confidence in science and technology would surely be shaken if he lived now. His optimistic observations on the rapid global circulation of knowledge and technologies practically make him sound like a post-operaista Negri of the nineteenth century. But he is surely still in the right in his argument with Malthus - it is possible to sustain the whole world's population comfortably. And his musings on the possibilities of a new education, activity that isn't drudgery, and the difficulties of sustaining inequalities when alternative methods already exist, in germ, can still provide some inspiration. -

Not a very good book, not particularly fascinating, I think it was written far too optimistically for such a book on capitalism, if you are discussing capitalism, then you should be sort of nihilistic with your approach towards capitalism, his optimism is very tedious, the way that it was written is not in the way that you would expect coming from a philosophy + politics-related book, I got to about pge 184 and said ''I can't read anymore of this book, this is far too boring'' luckily I was just about finished with the book, only one more chapter to go with this book and I would be finished, the only good thing about this book is that compared to The Conquest of Bread, there isn't 17 chapters, there's only 5 chapters, this book drags on for ages, the chapters are fairly long, and you keep wondering to yourself "when will the book be finished?'' You know one of those books where you can't seem to put the book down, it's too fascinating to stop reading, this book isn't one of them, it's dull and lifeless, not a very great book

-

If you're fascinated by industrial/agricultural history & love statistics, then this is a fascinating read. If you're not, you might struggle with aspects of this otherwise insightful & astute political analysis.

-

"Fields, Factories and Workshops Tomorrow by Petr Alekseevich Kropotkin, KnIAZ, (1975)"