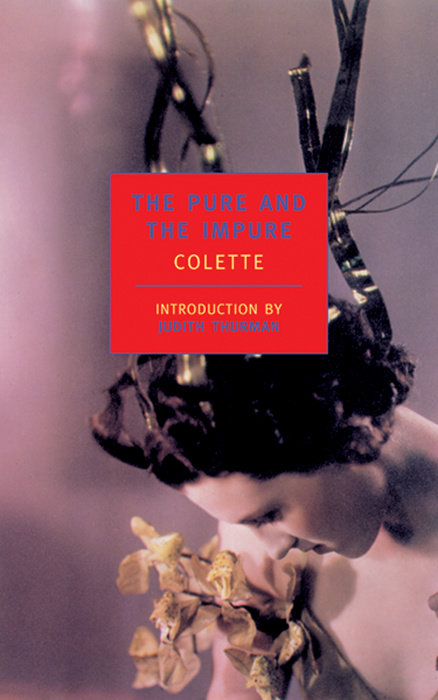

| Title | : | The Pure and the Impure |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 094032248X |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780940322486 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 208 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1932 |

The Pure and the Impure Reviews

-

The word "pure" has never revealed an intelligible meaning to me. I can only use the word to quench an optical thirst for purity in the transparencies that evoke in it—in bubbles, in a volume of water, and in the imaginary latitudes entrenched, beyond reach...

It is a peculiar mood this piece evokes, the kind of "you had to be there, without any knowledge of what the future would bring" sensibility that renders all modern day desire for Victorian Age living both misinformed and masochistic. Said sort of desire implies free time enough to breed such old world nostalgia, as well as the comfortable complacence that discourages any delving deeper into the sordid truth of the matter entire. If you wish to fall in love with such things, stick to the surface tension of vision made beautious by rare circumstance, and refrain from falling in. Should you be anything but white or male and some flavor of heterosexual, there is nothing for you here in full. Here in this work of choreographed fiction, there is not even that, refraining as it does from entitled portraits of one true love.

There, you will find the pretty poetics, the poignant potency, the shadow crystal every so slow by flickers of motion, cries, glittering eyes passing and praying and parsing out individuals for its own particular whims. Sexuality for same and both and every which way for boys and girls, for despite the records glutted with guns and beards and trappings of the masculine fashion, women are perfectly capable of preferring themselves to the opposition. There are simply less hot house institutions for ensuring virulent growth.This is because, with all due deference to the imagination or the error of Marcel Proust, there is no such thing as Gomorrah. Puberty, boarding school, solitude, prisons, aberrations, snobbishness—they are all seedbeds, but too shallow to engender and sustain a vice that could attract a great number or become an established thing that would gain the indispensable solidarity of its votaries.

Ah yes. Did I mention that the narrator has several bones to pick with prestigious Proust? Sentences scattered hither and thither that would easily be swallowed up by a single volume of the ponderous ISoLT, but where they strike, they strike true.

In these days, anything deviating from the (man + woman) norm was a sin, so all that is left is the self and a certain aesthetic the encompasses pleasure and pain alike. It is the senses that are at stake here, bounded among the extraneous side effects of emotion, desire, and even a small whiff of morality here and there, but slight. Ever so slight. The stories here are of those who survive until they do not, hiding, revealing, flitting behind their fantasies, every so often exiting forevermore when life has not sufficed. Good and evil have no place amongst these self-proclaimed monsters, self-sanctioning with every breath and act of love that even if not behind closed doors would prove ever so harmless. They reappopriate the glitz and glory of a world that caters only to the dichotomy, all in hopes of finding something along the lines of that Fruit of Knowledge that will never let them go back.

For here, there is the unnerving:For instance, a mere boy, issuing from the distant times when good and evil, mingled like two liqueurs, made one, gave an account of his last night at the Élysée Palace-Hôtel:

There is the delight:

"He made me feel afraid, that big man, in his bedroom..I opened the little knife, I put one arm over my eyes, and with my other hand holding the knife, I went like this at the fat man, into his stomach...And I ran away quick!"

He was radiant with beauty, with roguishness, with a kind of incipient madness. His listeners were tactful and cautious. No one exclaimed. Only my old friend C., after a moment, casually said, "What a child!" and then changed the subject.On my way, I would rap on the window of the garden flat where Robert d'Humières lived, and he would open his window and hold out an immaculate treasure, an armful of snow, that is to say, his blue-eyed white cat, Lanka, saying, "To you I entrust my most precious possession."

And above all, there is Colette, her thoughts, her memories, where her talents and sensibilities led her and what she has deemed suitable to be performed in prose. Take her hand, stay a while. Time has long left her worded world far behind, and there is as little hope of capturing it now as there was then. But a taste? That is guaranteed. -

"But what is the heart, madame? It's worth less than people think. It’s quite accommodating, it accepts anything. You give it whatever you have, it's not very particular. But the body... Ha! That's something else again! It has a cultivated taste, as they say, it knows what it wants. A heart doesn't choose, and one always ends up by loving."

Colette writings were on my wish list as long as I can remember. Her life and ideas of sexual liberation enthralled me with the very thought of it being played in the early 19th century. To pine for such independence, moreover live it to the fullest fancies me as even today in this post-modernization era sexual taboos thrive with the strongest clout.

Colette’s writings are a bit peculiar and candid without being mechanically strategize to create a pre-planned ambience. The exceptional quality can be observed in this book. Colette focuses on the eternal pursuit of jouissance, an extreme pleasure to pacify the bodily hunger with a prevailing element of love. She questions the legitimacy of love when engulfed with sexual bliss develops into an expression of narcissism or self-obsessed endeavor. All her characters in this novel are in a never ending pursuit of love defining their own rules yet never seem to have a happy ending. The several protagonists varying from:-

Charlotte:- a 45 yr old woman who tries her best to hide her true feelings from her ravishing young lover.

Renee Vivien:- Seek for acceptance and love in her several lesbian relationships, ultimately rendering to commit suicide with a lonely heart.

Lady Eleanor:- who live a quaint and indiscernible life with her companion Sarah for 53 years.

Pepe:- A Spaniard of nobility who was in love with rugged men in blue overalls.

All of them are chained in sexual inhibitions and failing miserably in achieving self- satisfaction over sought after pleasures. Colette’s notion of the quest to attain pure jouissance brings rejection and vacant contentment solidifying the “impurity” of any relationship.

Colette’s scripts are not strictly feminist or homosexual values; it is a novel implicating the idea of women flouting societal norms of conventional sex, power and love, by discovering their sexuality. Her open acknowledgement of homosexuality as a legitimate and external character and androgynous women delineates her rebellious temperament in a sexually repressed era. Colette’s callous abnegation for “normal” people is reflected in the following excerpt:-

"The viewpoint of "normal" people is not so very different. I have said that what I particularly liked in the world of my "monsters" where I moved in that distant time was the atmosphere that banished women, and I called it "pure."

"O monsters, do not leave me alone. . . I do not confide in you except to tell you about my fear of being alone, you are the most human people I know, the most reassuring in the world. If I call you monsters, then what name can I give to the so-called normal conditions that were foisted upon me? Look there, on the wall, the shadow of that frightful shoulder, the expression of that vast back and the neck swollen with blood. . . O monsters do not leave me alone. . ."

The book reveals the restless soul of disgruntled relationships, similar to what Colette experienced in her personal life. With two failed marriages and feral affairs she constantly longed for approval and love just like her characters. Thus, I wonder whether ‘love’ is the purity of pleasurable impurity. -

Please note that the above star rating is less indicative of the quality of the novel than of my shortcomings as a reader: I realize in retrospect that what I wanted was an engaging, gossipy yarn dissecting the sexual practices of the affluent and/or artistic circles Colette moved in in the fifty years spanning from the fin de siècle to her death just past the midway point of the 20th century... What I got instead was a nuanced, diffuse and delicately textured meditation on love, sexuality and sexual practice. And even though she is particularly interested in various "deviant" sexualities, the author—to her great credit, of course—is less interested in recounting details of lascivious excess than in trying to understand the motivations and psychology of sex in all of its diverse forms. In the end, there's hardly any sex to speak of.

The main reason I took up this novel was for its now-famous chapter devoted to poet and author

Renée Vivien, who was Colette's neighbor and (in a loose sense of the term) friend in the years leading up to Vivien's early, tragic death. And one can see why

Natalie Clifford Barney was appalled by the portrait—Vivien comes off as eccentric if not actually mentally unbalanced, and much of the rather sensational mythology that sprung up around her certainly has many of its roots here. But it's also not nearly as vicious as Barney regarded it as either, as Vivien comes off as a complex individual, lively and vivacious and intensely melancholic in turn. If it does come off as a rather sad depiction in the end, it's also deeply sympathetic and even a bit moving. And it's certainly the most vivid and absorbing section of the novel, perhaps because its the most concrete in its sharply-observed details (something Colette is masterful at) and the least ruminatory in nature.

I fully intend to return at some point with my expectations recalibrated and more attuned to the intricate complexity of Colette's project. And when I do, I expect that it will yield a higher star rating. -

There are glib moments here to treasure:

"I'm of the opinion...that in the ancient Nativities the portrait of the 'donor' occupies too much space in the picture."

and...

"What I lack cannot be found by searching for it."

and...

All amours tend to create a dead-end atmosphere. "There! It's finished, we've arrived, and beyond us two there is nothing now, not even an opening for escape," murmurs one woman to her protégée, using the language of a lover. And as a proof, she indicates the low ceiling, the dim light, the women who are their counterparts, making her listen to the masculine rumble of the outside world and hear how it is reduced to the booming of a distant danger.

But mostly is laying around and thinking or saying 'men are like ...' and 'women are like...' It's more complicated than that. We change seasonally, daily. Who I am depends on who you are, at that moment when we intersect.

Get me out of this opium den. -

The Pure and the Impure

I've just finished re-reading the only book of Colette I have ever read. When I first read it, so many years ago, my French was not up to the challenge - fortunately, that is no longer the case. It is evident from the earlier reviews that this book is many things to many people - indeed, I find when reading some of the earlier comments that I must remind myself that we are all talking about the same book, for it is certainly not evident.

To me, it is a collection of relatively brief portraits, usually emphasizing just one aspect of the person's character: the middle-aged woman with the lover over 20 years her junior; the past-middle-aged cockhound; the truly ruthless Don Juan; the lesbian poet who excels in every form of eccentric extravagance (and who is dead at 32); the aged and querulous lesbian actress; the Georgian lesbian couple in their bucolic Welsh cottage; a band of dishing queens from whom only two emerged as individuals - a man in his 70's who lives with his centenarian mother (!) and a crossdressing 17 year old butcher's apprentice, who, according to our author, shot himself in the face a few days after his somewhat less than successful appearance at her salon (!). These very partial portraits are drawn with great precision, if not subtlety, in a language often enjoyable to read; they merit savoring. The portraits are leavened with some rather airy, bordering on empty, theorizing about the differences between male-female and female-female relationships. Mildly irritating is her occasional tone of worldly grande dame observing the natives in their habitat (unhappily, she actually begins the book in this stance); much more irritating to me are her occasional generalizations (and not just in the reported conversations, but also in the narrator's voice) signaled by "toutes les femmes", "les hommes" and the like. And I wonder how many lesbians would agree that "only sapphic [my emphasis] libertinism is unacceptable" ?

In sum, this book is a unicum - I haven't read anything else like it. But I expect this will be the last time I read it...

Rating

http://leopard.booklikes.com/post/716... -

3,5 stars rounded up, because it's such a meditative joy to read compared to

Gay Bar: Why We Went Out... -

What I've learned is that when the goodreads description says 'erotic', it never is

-

לסקירה בעברית -

https://sivi-the-avid-reader.com/הטהו... -

Colette's The Pure and the Impure is a meditation on sexuality/sexual relationships. It was an interesting read but there were times when I had trouble following the narrative, and that's why I refer to this book as a meditation. Many times I would have to go back and re-read several paragraphs in order to understand what or whom or who Colette was talking to. But I did gather a great quote, one that I can relate to:

"'I am neither that nor anything else, alas,' said La Chevaliere, dropping the vicious little hand. 'What I lack cannot be found by searching for it.'" -

The Following Review Is Not Totally A Review, Rather, A List Of Thoughts On Colette and Queerness:

I first heard about Colette not for her writing, but as a member of the long list of people who Natalie Clifford Barney hooked up with. When I did a little googling, I found Colette dated someone even more interesting to me: The Marquis de Morny, who she caused a controversy by kissing on stage--and had a relationship with for six years.

The Marquis is person who seems to be perceived as a woman by the upset crowd watching the stage, by history, who relentlessly genders the Marquis as female, and (as I'll discuss in a minute) by Colette. But when you pay attention to the Marquis' behavior, you wonder what the Marquis' opinion was.

(Colette on the left, with the Marquis de Morny.)

The Marquis, who wore men's clothes almost always, and was followed by all sorts of "scandalous" rumors: That the Marquis had a double-mastectomy, that the Marquis had a hysterectomy, that the Marquis had the servants refer to the Marquis as Max, or as Monsieur le Marquis.

All very womanly stuff.

It's so bizarre to me that many people consider him a transsexual, but no one thinks to male-pronoun him. "He's a man, but no one in his lifetime called him one, so we're off the hook. Whew! I'd hate to make a dead transsexual happy."

Yeah, there's evidence for his transness. And maybe he wasn't trans. Because the Marquis is dead, I am open to people interpreting what they need to out of the Marquis. If the butch lesbians need him to be a butch lesbian, there's evidence for that. If the non-binary folks need him to be non-binary, there's evidence for that. I'm cool with with either. But I think that people at least need to be open to the idea that we're talking about a transgender person, and possibly a man.

I was very curious to read the chapter that Colette describes the Marquis, (identity hidden as "La Chevalière") and very sad when Colette never alluded to them as a couple. I didn't really expect her to refer to the Marquis as a man, but I thought she'd at least admit that they had been together, as she did so publicly on stage in front of an audience. But apparently not. She paints the scene as if she happened to have an in to the Marquis' fabulous dapper-butch parties, where (she remotely describes) the attendees spend a lot of money and take instruction on how to appear that most like a cisgender man. The most skilled is the Marquis, who takes the younger butches and trans men under his wing and instructs them in his ways.

Here's one very trans line from Marquis' chapter: "[A young man] gave to La Chevalière a name that made her blush with joy and gratitude: he called her "my father." (81)

---

As for the rest of the queer content in this book:

Colette describes Renée Vivien, the tragic lesbian poet, English-born, French-by-choice, and a fellow woman listed on Natalie Clifford Barney's conquests. Colette isn't a big fan of Vivien's poetry or her life choices, but I find her first-hand profile of Vivien interesting (and sometimes humorous).

Colette also describes hanging with a group of queer men, and she isn't very kind to them. Like the Marquis' friends, she goes into anthropological mode, and gives the members of the group all one character. Though it's an interesting glimpse into the queer history of her time, it's not a very kind portrayal. (She refers to one person who came once, wore women's clothes (again, another proto-trans figure) who she describes unkindly and then matter-of-factly reports that the person kills herself. Not the kind of paragraph that plays well to trans audiences.)

One chapter she spends describing two Welsh women she never met who lived together, and describes them as silly, and says that women can't sustain a relationship together.

Maybe Colette is censored (this was Nazi France that she was writing in), maybe Colette is censoring herself, but there was no unambiguous positivity towards any of these queer people that she seems to keep hanging out with. Remembering that Colette is queer herself, probably some flavor of bisexual, I'm not sure how to read her tone here. Perhaps she's interpreting choices she made in her life ("I prefer relationships with men") as universal human condition ("Everyone should be straight.") I'm making inferences; I have no idea. I wonder if there's some internalized homophobia happening, or perhaps she feels like she has to tamp down her discussion of queer people with some negativity in order to maintain her reputation, or whatever.

Maybe I got used to Colette's style, but by the time I read

The Tender Shoot and

The Vagabond, Colette briefly describes lesbians and was much more sympathetic. In the Vagabond, though the fictional narrator uses some word like "reprehensible" for lesbians, she's mad when her boyfriend insults her lesbian friend's sexuality. Colette initially pulls something similar in the story Bella-Vista in the Tender Shoot. (though ultimately Colette-the-author is pulling too many strings, and the couple is bizarrely revealed to be a straight couple, but apparently the man is a criminal on the run, so he disguises himself, which Colette-the-narrator is appalled more than if they had been as they appeared. Is it transphobic? Is it homophobic? Who knows.)

This book is invaluable as a peek into the lives of queer people of turn of the 20th century Paris. It's also great insight into the lives of Marquis de Morny and Renée Vivien. If you're just a casual queer reader who isn't excited by queer Paris of a hundred years ago, I'm not sure I would recommend the book. -

hm . nosy bitches who never say anything in conversations rep <3 but also why are you writing about gay people when it seems like you hate them < / 3

i liked the ppl she would bring up!! and then did not like her commentary!!! the welsh og cottagecore lesbians w/ a cow named margaret are actually definitely happy i promise!!!!

giving eve babitz but worse < / 3 -

Colette's

The Pure and the Impure is a book about the author's conversations with her friends about non-heterosexual sex. Although she was married multiple times, Colette was by no means a stranger to other forms of gratified desire.

I got the feeling that Colette had difficulty expressing herself on the subject -- not unusual mores being what they were in the 1930s. She always seems on the point of expressing herself, but backs away in a series of ellipses or other evasions. Nonetheless, this is a book that was breaking new ground.

Despite that, I found the book to be not only readable but fascinating. -

I found this really underwhelming, and half the time wasn't sure what she was going on about. Partly I think that was because of the flowery writing, but also I felt like this was just difficult to follow. The anecdotes and reflections on love in all its forms were fascinating, kinda dated but fascinating.. am now obsessed with Renée Vivien.

-

The Pure and the Impure has a fantastic introduction and explores many interesting themes and characters, but I couldn't get past the meandering plot structure, the stereotypes, or the purple prose.

-

THE PURE AND THE IMPURE is a book written in French in the 1930s that teaches you about how love and sex works. I read the whole thing (translated into english) and I'm still bad at love and sex, but it did two of the things I'm looking for when I read a book: it articulated some things that I've observed and felt, but never told to anyone, and it broadened my horizons by showing me the world through a different brain.

Two things that it didn't do is make me laugh or have any lesbian sex in it. Which is OK. Neither of those things are "deal breakers" for me. A book called "The Pure and The Impure" is just not going to be funny. (Plus, French people aren't that funny. Except Marcel Marceau and Le Pétomane.) The lesbian sex thing was a bit more of a letdown, since this looked like the type of book that was going to have a lot of lesbian sex in it, but that's fine too. I don't read to get aroused. I just thought I should warn you.

The format of the book is basically a big rant. Each chapter is about a person or couple who Colette has known, who was queer or promiscuous or both. Like a lot of rants, it can get tedious, and sometimes you want to shake the ranter and say "what the fuck are you talking about?" but as a ranter myself I found it all kind of endearing. Sometimes Colette seems to be overthinking things, and sometimes she seems to be painting with a broad brush, and that's how I am too.

The most relatable part to me was when she said, of herself and one of her male friends, "He and I and others like us come from the distant past and are inclined to cherish the arbitrary, to prefer passion to goodness, to prefer combat to discussion." AMEN, sister! That is the type of person with whom I want to discuss the big issues: someone who is willing to throw a big sweeping statement out there and see if it sticks.

Unfortunately, since she's French, Colette also comes across as a know it all. She'll say things like "I am alluding to a certain hermaphroditism which burdens certain highly complex human beings" and you just want to smack the espresso out of her hand. Really, Colette? Are you and your friends really so highly complex? Passages like this, for me, evoke Leonardo DiCaprio's slave owner character in Django Unchained, who talks in a refined, intellectual voice all the time to mask the fact that he's dumb as shit. But, like I said, I'm a ranter too, so I can forgive these things, as long as you're not measuring people's skulls.

The most horizon-broadening thing for me was the "sensuality" of the writing. I don't mean this in the erotic sense (remember, there are NO LESBIAN SEX scenes in this book) but in the sense of talking about the senses. (Does that make sense? Heh heh.) Colette, since she is French, is very in touch with the smells and tastes of things, and reads into what people are wearing. (Sorry, French people, I told you I like to paint with a broad brush.) I never describe smell, taste, or fashion in my own writing, mostly because I have no sense of smell and a very limited sense of taste and fasion, and this book made me feel a little "basic" for that, in a helpful way.

Overall, I'm going to have to give this book a 0/1, because it got a pretty tedious at times, and probably should've just been an essay, but I'm glad that I was forced to read it. (It was this month's selection in my book club.) I like Colette, and in fact I think I have a crush on her. The description of the acoustic qualities of the word "pure" at the end was fantastic, and tied the whole thing together. (The word "pure" in French is "pur," so it translated well.) Also, this book looks good on my shelf. It makes me look like a "highly complex human being." Maybe--hopefully--the kind of human being another human being would want to have sex with. -

1. What an odd kind of a book. It's one of those early twentieth century novels that seems as equally a memoir - the line between fiction and autobiography is, well, not much of a line. I mean, The Pure and the Impure is definitely a novel. But it's not simply a novel. "Colette" recalls conversations with fictionalized (some of the fictionalizing is more robust than others) acquaintances, her friendships and so on, on the topic of love/sex. So far so Collete, I suppose - her work hews rather closely to her life.

2. Judith Thurman's introduction thinks rather more highly of Colette's sexual politics (actually, Colette's own phrase, "sexual militant" is rather more apt, and Thurman is right to adopt it) than I do. But there is something revolutionary about Colette's writing on sexuality, and not just "for her time." For our time too. I think it's something like . . . she foregrounds subjectivity. She rejects structures - which is definitely optimistic and maybe delusional, but sort of admirable for all that."I'm devoted to that boy, with all my heart. But what is the heart, madame? It's worth less than people think. It's quite accommodating, it accepts anything. You give it whatever you have, it's not very particular. But the body . . . Ha! That's something else again! It has a cultivated taste, as they say, it knows what it wants. A heart doesn't choose, and one always ends up by loving. I'm the living proof." (22)

3.

Secrets of the Flesh, which is excellent, is now a bit hazy in my memory but Colette's life is vivid enough that even those hazy memories are of some use. Again, it's not a thinly-veiled autobiography or anything - but it's helpful to know a bit of what's going on already because, as Thurman's introduction notes . . . Colette doesn't go out of her way to make this an easy read. It is easy and pleasant to read, but difficult to figure out. There is much that's merely alluded to - is there an annotated edition? There ought to be. - and little that is explained, which is odd, maybe because it's a fairly discursive kind of book. -

Claramente se trata de una obra «extraña» como gusta de calificar al prologuista de la edición española de ‘Globalrhythm’, pero cuya base fundamental son las memorias, especiales sí, pero memorias. Comienza la obra en una atmósfera típicamente decadente: un taller fumadero opio habilitado en una casa, y a partir de ahí se sucederán escenas, idas y venidas de personajes, en su mayoría femeninos, y saltos en el tiempo no bien definidos.

‘Lo puro y lo impuro’ (1932) se podría resumir así en una suerte de periplo sentimental donde aborda, ya como interlocutora en escenas dialogadas, ya como narradora en primera persona por medio del monólogo, asuntos tales el mito del donjuanismo, el amor homosexual en sus diferentes facetas, los celos, el travestismo y la toma de un rol masculino en las relaciones lesbianas, etc.; en general el tono es sereno y reflexivo como en la parte referida al diario de Eleanor Butler y su sempiterna y sumisa compañera Miss Ponsonby, donde lo anecdótico, aunque no predomina, también tiene su espacio como en esepasaje referido a la poetisa Renée Vivien, de la que vierte una imagen quebradiza y algo infantil inclusive.

En definitiva, el lector hallará aquí una obra profunda pero alejada del lirismo que se podría presuponer, con una tesis que propugna la emancipación de la mujer por medio de su sexualidad, pero sin concesiones al buenismo. Colette tenía una muy particular forma de entender las relaciones humanas y amorosas, y con la distancia que los años le otorgaban ya, y de forma más implícita que explícita, pincela lo que ella entiende por lo puro y lo impuro. Y es que ‘Lo puro y lo impuro’ podría así interpretarse como una guía de confidencias, un paseo de selectas reflexiones para mujeres y hombres, lectores todos, que gusten embeberse con la poliédrica forma que representa la propia experiencia humana en su faceta social.

«La palabra “puro” no me ha revelado su sentido inteligible. Me limito a aplacar una su sed visual de pureza en las transparencias que las evocan» (Colette). -

I'll admit the embarrassing part up front: yes, I'd meant to read Colette for quite some time but, yes, also, the fact that a movie about her just came out gother back on my radar. For that I am grateful, and also a little abashed. (I still have not seen the movie and cannot vouch for it, though the reviews are thus far kind.)

This is apparently not the most characteristic of Colette's books, but I found it quite beautiful and insightful, in its oblique way. It's more a memoir and a meditation, the kind of blurred genre work that other interesting writers have recently been and are currently deploying (Dodie Bellamy, WG Sebald, some others). It's a frank, carefully observed, poetically rendered report from quite a different time and place, yet the insights it has on the nature of desire, and the ways people talk to each other given their various interests and backgrounds, seem sound, ring true.

(So, anyone vouch for the movie?) -

A sensuously written peek into the Parisian erotic underworld of the early 19th century. While it must've been scandalous when first published, much of it seems quaint now. Execept for the lesbian opium den orgies, that's still pretty titillating.

"He waved both hands in a complicated gesture which fleetingly indicated his chest, his mouth, his genitals, his thighs. Thanks no doubt to my fatigue, I was reminded of an animal standing on its hind legs and unwinding the invisible. Then he resumed his strictly human significance, opened the door, and easily mingled with the night outside, where the sea was already a little paler than the sky.” -

My boss' wife adores Colette, cannot say enough about her greatness. In part, I am not easily engaged by her sort of dreamy post nineteenth century female style. I expected to be drawn in by the sexually liberated woman I think she was. I was somewhat intrigued by elements of the world she creates with her writing, an autobiographical portrayal of the bohemian Paris of the early 20th century. But the style didn't do it for me, I think I like a rawer more contemporary style. Lots of people love her though, so it might be worth a read.

-

I love Colette, but this left a nasty aftertaste. While the sketches of Renee Vivienne and her old flame Missy were superb, it had many odd- and somewhat offensive- views about lesbians and their prospects of happiness, which naturally struck in my craw. Stick to the Claudines and her other novels if you don't want your image of the great writer (not such a liberal after all, alas) to be tarnished.

-

Don't be fooled by the main description. This book is self-absorbed and dripping with sentimentalism. The majority of it is a description of social impressions and emotional reactions. Very airy stuff without much substance.

-

A clairvoyant's diary, of days passed in Paris' demimonde, exquisitely written.

-

When published, many people found this book shocking. I suspect that many people still would. I am not one of those. I didn't much like it because I simply wasn't interested.

-

I found this book rather boring. Couldn't finish the last 1/4 of it.

-

amazingly written, in the first half amazingly gay, in the second half kinda heteronormative

-

This is so ahead of it's time! Very interesting, though dense and somewhat random at times.

-

In the Biblical book of Ecclesiastes, the preacher does a thorough investigation to see if there is anything under the sun that can satisfy the longings of the human heart (“I said to myself, ‘Come now, I will test you with pleasure to find out what is good.’ But that also proved to be meaningless.” Ecclesiastes 2:1). Similarly, French author Colette provides a series of vignettes that investigate the power of human desire. As Judith Thurman’s Introduction sagely notes, this novel is “not only a penetrating treatise on homosexuality, promiscuity, misogyny, and the ancient enmity between the sexes, it is a meditation on the way human beings eroticize – with tragic consequences – their primal, affective bonds.” The vignettes are powerful. Colette considered the stories to comprise her best work, "the nearest I shall ever come to writing an autobiography." Colette’s prose are lavish (“She was constantly giving things away: the bracelets on her arms opened up, the necklace slipped from her martyr’s throat. She was as if deciduous. It was as if her languorous body rejected anything that would give it a third dimension.”). Colette concludes her investigation by exploring the role of jealousy in human relationships. The author quipped to a friend, “This is a sad book, it doesn’t warm itself at the fires of love, because the flesh doesn’t cheer up its ardent servants.” Perhaps Colette is echoing Ecclesiastes, wherein the preacher concludes his investigations by declaring “everything is vanity”?

-

Colette, tu m’avais manqué. Je m’ennuyais de ta sensibilité et de ton écriture unique. Ton langage est si incorporée de ta personne, ton intelligence se retrouve dans chacune de tes phrases et tu permets d’exprimer avec aisance les espaces flous de nos gestes et sentiments qui sont parfois si difficiles à définir en texte. Tu parviens par des images à préciser les sentiments que tu veux nous invoquer.

« Tandis que la voix de D…., étouffée d’attendrissement, murmure comme un feuillage » ou « Mais cette jalousie, par exemple, qui lui fleurissait au flanc comme un oeillet noir, ne la lui ai-je pas trop tôt arrachée ? »

Je t’admire évidemment.

Cependant. Lorsque tu ne m’accapares pas de tes images magnifiques, ton propos est un peu décousu (plus que d’habitude) et ne me permet pas d’en ressortir grandi d’avoir lu tes élucubrations (quel beau mot qui ressemble à

Un crustacé non??) Je me perds et plus grave encore je m’ennuie… COLETTE tu es tout sauf ennuyeuse… alors cesse tes contradictions et vient m’éveiller je m’endors entre tes lignes et j’ai froid.

Bravo pour l’ambiance vaporeuse de fumée d’opium que tu rappelles de temps à autres par la vapeur, la brume, etc. Très cool

3.5/5

Xoxo

JUPAQ89 -

In the early 1990s I saw a film called BECOMING COLETTE. Ever since I've always been intrigued by COLETTE. I came across this book and decided to read it after reading the first sentence in the INTRODUCTION page:

THE PURE AND THE IMPURE is an investigation into the nature and laws of the erotic life.

It was a bit of a yawn 'here and there'; however, after completing the book and doing my review of the sentences that impacted me I realized that I did come away from it with an interesting view from the eyes of Colette (who always considered THIS one her best book).

Also, author Erica Jong wrote: "Colette has always seemed to me the most authentic feminist heroine of all women writers."

Here are the lines/sentences in THE PURE AND THE IMPURE that made me raise an eyebrow for some reason or another:

A child of either sex, she perceives, has urges to penetrate, devour, and possess, to be cherished, dominated and contained.

For Colette: To be pure means to be unhindered by any conscious bonds of need or dependence, or by any conflict between male and female drives.

THE PURE AND THE IMPURE is not only a penetrating treatise on homosexuality, promiscuity, misogyny, and ancient enmity between sexes, it is a meditation on the way human beings eroticize---with tragic consequences---their primal, affective bonds.

The strong take the offensive: they attempt to recover an illusion of wholeness through domination, and they become the sadists and seducers of both sexes.

…any shut-in and unfamiliar place makes us uneasy.

…so few women know how, with empty hands, to remain motionless and serene.

The average man overflows with confidential talk when he is with a woman whose frigidity or sophistication sets his mind at rest.

“I was never spared a single embrace by any of them.” (He did not say “embrace,” but used a blunter term that refers to the terrible paroxysm of male sexual satisfaction.)

Like most men capable of servicing (if I may put it that way) a great many women, possession, which is lightning quick, provoked in him a wretched feeling of hopelessness.

I have always greatly appreciated his confiding in me and I hope our confidential talks are not ended.

“I talk to him, then, about Don Juan and tell him I’m surprised that he has not yet written a Don Juan novel or play, and he gives me a compassionate look, shrugs, and charitably informs me that “period plays” are as out of fashion as cape-and-sword romances. And suddenly he exposes the child hidden in the heart of every professional writer, a child obstinately infatuated with technique, flaunting the tricks and wiles of his trade.”

“Don Juan, believe me, my dear, was another one of those men who think only of taking, another one of those grasping men whose way of giving is no better than what they give.”

There comes a time in LIFE when one feels on safer ground alone than when trying to find pleasures with another.

He has everything. He’s one of those men I call ‘the well-endowed’. He has an extraordinary animal magnetism, a handsome head, silver threads among the gold now, of course, but there’s still a look of youth about him…”

Youth is not the time to seduce, it is the time to be seduced.

“What memory do you believe you left with the women, with most of them?”

“Why, without a doubt, a feeling of not having had quite enough.”

My eyes rested on his fine mouth, I reflected that there was something about it that aroused ideas of sweetness, of sleep, something secret and gentle and sad—and still youthful. And I remembered the adage: “A kissed mouth never grows old.”

I wanted him to give way to anger, to make some kind of row that would prove him to be illogical, weak, and feminine---what every woman wants every man to be at least once in his life.

Listening is an effort that ages the face, makes the neck muscles ache, and stiffens the eyelids looking fixedly at the speaker….not only listening, but interpreting.

’Did you never give a woman time to get used to you….to relax?”

Oh, the charm of a sleeping man, how vividly I recall it! From forehead to mouth he was, behind his closed eyelids, all smiles, with the arch nonchalance of a sultana behind a barred window.

“What I lack cannot be found by searching for it.”

Unhindered by any ambiguity, she spoke openly, and what she spoke of was not love but sexual satisfaction, and this, of course, referred to the only sexual satisfaction she knew, the pleasure she took with a woman.

I fear there is not much difference between the habit of obtaining sexual satisfaction and, for instance, the cigarette habit. Smokers, male and female, inject and excuse idleness in their lives every time they light a cigarette.

A woman whom a man betrays for another man knows that all is lost. Containing her cries, her tears, her threats, which comprise the main part of her forces in an ordinary case, she does not struggle, but digs in or says nothing, fulminates scarcely at all, occasionally tried to find the way to an unrealizable alliance with the enemy with a sin that dates as far back as the human race, a sin she neither invented nor approved…..Disillusioned she renounces with bitter hatred and carefully conceals her great uncertainly, wondering, “Was he really destined for me?”

Homosexuals: They know precisely what they like and dislike. They are aware of the perils of their chosen life, know the bounds of their particular prejudices, and if they pay lip service to caution, they often forget it.

He pressed both hands against his heart that was at long last torn, and shut his lips. For a man has the right to murmur audibly “Paloma” or “Kelly” and to kiss in public the portrait of a lady, but he must stifle the names of “Chad”, “George” or “Christopher”.

It would be a pity to let the memory of all this be lost.

It is wise to apply the oil of refined politeness to the mechanism of friendship.