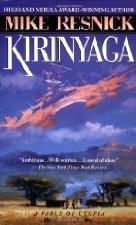

| Title | : | Kirinyaga (A Fable of Utopia, #1) |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 034541702X |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780345417022 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 293 |

| Publication | : | First published November 1, 1988 |

| Awards | : | Hugo Award Best Short Story for “Kirinyaga” (1989), Nebula Award Best Novelette (1988), Locus Award Best Short Story (1989), SF Chronicle Award Best Short Story (1989), HOMer Award Best Novel (1998), Seiun Award 星雲賞 Best Overseas Long Fiction for "Kirinyaga" (2000) |

Contents:

One Perfect Morning, with Jackals (1991)

Kirinyaga (1988)

For I Have Touched the Sky (1989)

Bwana (1990)

The Manamouki (1990)

Song of a Dry River (1992)

The Lotus and the Spear (1992)

A Little Knowledge (1994)

When the Old Gods Die (1995)

The Land of Nod (1996)

Kirinyaga (A Fable of Utopia, #1) Reviews

-

Kirinyaga is what the locals tribes call Mount Kenya. The distinction is important because it marks the refusal by the traditionalist Kikuyu to accept the Western values, especially in view of the extensive environmental damage, overpopulation and loss of cultural identity they are confronted with in the twenty-second century. So, when new technological advances open up the Space for the creation of human colonies on carefully terraformed and climate controlled planetoids, these tribesmen decide to leave Kenya and go live by the rules of their forefathers in a Utopian society among stars.

The principal artisan of the movement is Koriba, an elderly, Western University educated Kikuyu, the spiritual leader of the colonists and the liant that holds together the eight novellas included in this Mike Resnick collection. The stories were published independently over more than one decade, but there is a chronological and logical progression in the study of a Utopian society that justifies the treatment of the sum of these episodes as a proper, unitary novel.

I was first attracted to the title by its non-Western source of inspiration and by the numerous genre awards the novellas have received over the years. I have also admired another Mike Resnick story set in Africa, addressing the nature of humanity as a whole: Seven Views of the Olduvai Gorge . Kiriniaga delivered on my expectations on multiple levels, and the author’s boast that it is his best work seems justified. The application of myths, legends and parables in the description of he Kikuyu culture and the complete rejection of modern technology places the novel in the “soft” SF, sociological study category, and the issues tackled here – identity, the individual needs versus the community needs, sustainable development, democracy versus tyranny, reckless progress versus conservative stagnation, traditional values versus freedom of thought, globalization versus cultural diversity – have direct application to problems we are already confronting in the beginning of the third millenium.

Because the novellas were conceived to function both as stand-alones and as stepping stones in the efforts of Koriba to create the perfect society for his people, there is some overlap and repetition of themes. Each episode begins with a parable about Ngai, the supreme deity of the Kikuyu, followed by the exposition of a current crisis Koriba has to defuse, and ending with the moral, the lesson of the day that the mundumugu wants to impart to his audiences.

- What exactly is a mundumugu?

- You would call him a witch doctor. But in truth the mundumugu, while occasionally casts spells and interpret omens, is more a repository of the collected wisdom and traditions of his race.

Koriba in his role of mundumugu assumes the mantle ultimate authority, of judge and jury of every tresspassing against the racial traditions that he claims are the only road to follow for the creation of Utopia. He wields the power of Ngai (ironically, through a computer screen communicating to climate control supervisors), and when his parables are not enough to sway his villagers, he is not shy of cursing the entire community until he gets his wishes.

(1) One Perfect Morning, With Jackals is the prologue, describing the departure from a homeland where all the big game is extinct, the sacred mount is now a megalopolis, and the people have embraced fully the global culture. Favorite quote:

To be thrown out of Paradise, as were the Christian Adam and Eve, is a terrible fate, but to live beside a debased Paradise is infinitely worse.

(2) Kirinyaga is the first story set in the new lands, and one of the most controversial because it asks the readers if a traditional population has the right to adhere to its superstitions and outdated rules. In this case it is infanticide, but you can expand the question to cannibalism, scalping, underage marriage, Sharia, circumcision or gay rights. Koriba argues in favor of maintaining Kikuyu identity by any means necessary, as the only society cabable of living in harmony with its environment.

(3) For I Have Touched the Sky is my favorite story, and it deals with access to knowledge and informed choices, a theme that will be revisited later in the novel. Here, one of the smartest young girls in the village comes to work for Koriba and incidentally gains access to his computer. She has a wonderful thirst for knowledge and natural curiosity, but in a traditional Kikuyuy society women are restricted to fieldwork and housekeeping, servants to the power of their menfolk.

- Once a bird has ridden upon the winds, he cannot live on the ground.

- Do all birds die when they can no longer fly?

- Most do. A few like the security of the cage, but most die of broken hearts, for having touched the sky they cannot bear to lose the gift of flight.

(4) Bwana deals with the problem of an agricultural, pacifist society facing a warrior culture. In this case a Masaai hunter is called to the village to help with hyena attacks against children, only to refuse afterwards to leave, bullying the locals into submitting to him as the leader of the pack. Koriba needs all the cunning of his old tales to find a solution to get rid of the tyrant without appealing to the world’s supervisors.

- What kind of Utopia permits children to be devoured by wild animals?

- You cannot understand what it means to be full until you have been hungry. You cannot know what it means to be warm and dry until you have been cold and wet. And Ngai knows, even if you do not, that you cannot appreciate life without death.

(5) The Manamouki questions the welcoming of strangers inside the Kikuyu Utopia, as a couple of immigrants come to Koriba’s village. No matter how hard the Western woman tries to live by the rules of the Kikuyu, she is not accepted by the other wives who look at her with envy and distrust.

There are many different notions of Utopia. Kirinyaga is the Kikuyu’s

(6) Song of a Dry River returns to the theme of women in a traditional society, in this case Mumbi: an old lady who is “put out to pasture” by the younger wives of her son, but still feels the need to work and be useful. The story also marks a turning point in our perception of Koriba from a benevolent, if strict, traditional ruler, to a vengeful and petty tyrant who cannot brook any challenge to his absolute authority. Can a society be considered Utopian if not all its members are happy to live in it?

Perhaps there are no Utopias, and we must each be concerned with our own happiness.

(7) The Lotus and the Spear is another take on the issue of the pursuit of happiness, as Koriba is confronted with a series of suicides among young men who feel depressed by the lack of challenges and the lack of any real prospects for the future in the Utopian society they live in. All that they have to look forward to is inheriting the house and the herds from their fathers, marrying, raising children and letting their women work the plots of land.

From time to time I cannot help wondering what must become of a society, even a Utopia such as Kirinyaga, where our best and our brightest are turned into outcasts, and all that remains are those who are content to eat the fruit of the lotus.

(8) A Little Knowledge is about Koriba’s search for the next mundumugu, the one who will carry the torch of his dreams to the next generation. (“I sought a boy who grasped the difference between facts, which merely informed, and parables, which not only informed but instructed. I needed a Homer, a Jesus, a Shakespeare, someone who could touch men’s souls and gently guide them down the path that must be taken.”) He picks up Ndemi, the brightest child in the village, and spends years apprenticing him to the job, only to discover that the boy is capable of reasoning by himself and doesn’t necessarily agrees with his master’s philosophy.

It was you who taught me how to think, Koriba. Would you have me stop thinking now, just because I think differently than you do?

(9) When The Old Gods Die describes the ultimate defeat of the Utopian dream of Koriba, the final capitulaton of Ngai in front of progressive new ideas. It is time for Koriba to recognize that his Utopia may be different from the Utopia desired by the rest of his Kikuyu community. And a possible conclusion is that a perfect society cannot be frozen in time and must provide for new ways of thinking and new challenges.

You can direct change, Koriba, but you cannot prevent it, and that is why Kirinyaga will always break your heart.

(10) The Land of Nod presents the inglorious return of Koriba to the Westernalized Kenya, an outcast from his Utopian Kirinyaga, a living anachronism that cannot unbend and see the positive sides of progress, looking only at the destructive aspects of the new world. Like one of the extinct animals that once ruled the savannah, he must pass on into a mythical realm of legends like his once all powerful god Ngai.

The thing I had not realized is that a society can be Utopian for only an instant – once it reaches a state of perfection it cannot change and still be a Utopia, and it is the nature of societies to grow and to evolve.

Highly recommended. -

5.0 stars. WOW!! This was an exceptional collection of inter-connected short stories that should be seen as one complete story. The cosmetic premise of the of the stories is about a group of 22nd century Kenyans unhappy with its evolution into "another European city" who emigrate to a planetary colony in order to live simply and in harmony with the land as their ancestors did. The real or underlying premise of these stories are about the struggle of one person against the inevitability of progress and change.

This struggle is shown through the eyes of Koriba, the colonies mundumugu (i.e., holy man) as he attempts to keep outside influences, ideas and technologies from "contaminating" the culture of his people. Many of these "conflicts" made it very difficult to "sympathize" with Koriba's position given my, and presumably most readers, "Western" viewpoint (i.e., killing an infant because it is "cursed", leaving the elderly and infirm outside the village at night to be consummed by hyenas and refusing life saving medical services). However, even when we end up disagreeing with his position, Resnick does a great job of making the reader see these issues through Koriba's eyes so that at least we understand him. Not an easy thing to do and Resnick does it superbly.

The tale of Koriba and the colony of Kirinyaga are told in a series of connected short stories that, when taken together, is the most HONORED collection (in terms of major and minor awards and nominations) of short stories in the history of Science Fiction (see below for list of MAJOR awards only). This is definitely a worth-while collection and a SUPERIOR achievement by a great author. HIGHEST POSSIBLE RECOMMENDATION!!!

Table of Contents:

One Perfect Morning, With Jackals

- Nominee: Hugo Award

- Nominee: Locus Award

Kirinyaga

- Winner: Hugo Award

- Nominee: Nebula Award

- Nominee: Locus Award

- Voted to Locus All Time Best Short Story List

For I Have Touched the Sky

- Nominee: Hugo Award

- Nominee: Nebula Award

- Nominee: Locus Award

Bwana

- Nominee: Locus Award

The Manamouki

- Winner: Hugo Award

- Nominee: Nebula Award

- Nominee: Locus Award

Song of a Dry River

The Lotus and the Spear

- Nominee: Hugo Award

- Nominee: Locus Award

A Little Knowledge

- Nominee: Hugo Award

- Nominee: Locus Award

When the Old Gods Die

- Winner: Locus Award

- Nominee: Nebula Award

- Nominee: Hugo Award

The Land of Nod

- Nominee: Hugo Award

- Nominee: Locus Award

-

One of the best books I read this year, deservedly considered sci-fi classic. Actual review might come at some point later.

-

Después de verla en varias listas de mejores libros de Ciencia-Ficción recomendados y comprarla a muy buen precio en Gigamesh tuve un par de intentos de empezarla y el primer capítulo superaba mi interés y mi capacidad de "suspensión de la realidad". Ahora, una vez superado ese primer capítulo le libro se lee solo. Como "fix-up" de historias previas el conjunto está completamente engranado con la ventaja de que cada parte tiene sentido por si sola. Además, a pesar de llamarse este volumen "Kirinyaga" contiene esa novela y también su secuela "Kilimanjaro" que no es una continuación directa pero se apoya y disfruta completamente como contraste.

El libro cuenta en cada una de las partes (Kirinyaga y Kilimanjaro) dos formas de Utopía en las que empezar de nuevo en un planeta terraformado y habitado exclusivamente por habitantes de una misma etnia o nación y siguiendo unas costumbres particulares de forma más o menos rígida o flexible. Es un libro más de Ciencia-Ficción "blanda" en torno a la evolución o no de las sociedades y aprovechando las leyendas y cultura africanas. Un gran libro que deja un poso excelente y que se merece estar entre lo mejor que leí este año. Cinco estrellas *****. -

Solo con el artículo final del propio autor ya merecería la pena.

Es Resnick en estado puro, la demostración más clara de cómo usar la ciencia ficción para tratar cuestiones que nos afectan aquí, ahora, en la vida real. -

I was torn on this one. I wanted to like it going in and was actually captivated by the opening story, "One Perfect Morning, with Jackals". That was a great introduction to the new world set up by the Eutopian Council (clever name, that) called Kirinyaga, an attempt to get back to the roots of the Kikuyu tribe of what we barbaric Europeans call "Kenya".

And here's where the being torn comes in. As I read story after story, I realized that I didn't like the narrator, Koriba. At first I'd sympathized with him, but after some of his rulings as mundumugu, I wanted someone to leave him out for the hyenas. Then I decided I didn't much care for the stories as a whole. Each one started with an animal parable told by Koriba to hissheeppeople, in order to teach them the evils of European influence and the godliness ofKoriba himselftheir deity, Ngai. Then something would happen in the village, someone would attempt tothink for themselvesexplore the forbidden technology or culture of Europe. Or of the Kenyans from Earth, which Koriba referred to as "Black Europeans". Koriba would declare them to be wrong andbully or blackmailtell them parables to show them the error ofnot doing as he saysturning from the path of Ngai.

Anyway, the final chapter/story is "The Land of Nod", and it brings the entire book full circle, creating a satisfying and reasonable ending for the story as a whole. Satisfying beginning, satisfying ending. Hmmm....Lots of books can claim one or the other, but both?

So I thought about it. At first, I planned to give it a 2-star. It seemed to fit the "it's ok but I didn't really love it" definition of a 2-star. Or to be more blunt, "didn't really like it."

But I did. At times. I liked the story "For I Have Touched the Sky" quite a bit. Had I read this by itself, I would have been "wow!" It was heartbreaking and touching, and by the end of it I was . While the other stories weren't as effective as this one, they did hit me in a similar way.

I think that had I read the stories as they originally came out, I would have appreciated them more. But all at once, they became rather redundant and tiring. I'll give it a 3-star because when I did like it, I found it to be very effective and touching. It wasn't consistently touching all the way through, though. So 3 is where I'll settle... -

This is the book I usually mention when they ask me: “What’s a book that you consider a masterpiece and that nobody knows about?”.

I really loved Kirinyaga, it reflects a lot of today's reality, expecially our world's quick changes, and its many conflicts between past and present. An old scientist from Kenya, desperate because the "good old days" of Kenya's uncontaminated tribal life have gone, decides to recreate that world artificially, on another planet. Despite the futuristic concept, this is not much of a science fiction book, it's rather speculative fiction, or a book of ideas. The stories are interconnected, and they are part of the same overarching narrative. Elements of traditional Kenyan culture, African poetry, and some serious reflections on cultural changes are interwoven in this highly original work. Some stories have a ingenuity that reminded me of Sherlock Holmes stories, some others are truly moving. The main charachter may result annoying and arrogant, but by the end of the last story you also understand what the author thinks of his philosophy, and everything makes a little more sense. At least it did to me.

A few years ago I wrote the author a note complimenting him, and he cheerfully replied saying "Thank you!! Check out what else I can do!!", and he listed a few more of his books. -

The Good:

The writing is brilliant, the story thought provoking, and the setting and characters utterly vivid. The ending is perfect.

The Bad:

It’s as much a morality tale as a science fiction story, so there is a mild undercurrent of preaching. The story concerns a collective of 22nd century Kikuyu (a Kenyan ethnic group) nationalists who emigrate to their own terraformed world to live in the manner of their stone age ancestors. This fact alone makes their motivations difficult to understand from the beginning. Also, the episodic nature of the novel detracts from its flow and pacing. Lastly, as far as I know, Mike Resnick is not a member of the Kikuyu people, so this book probably offends someone.

'Friends' character the protagonist is most like:

Koriba is the visionary prophet of a past long dead. He is single-minded in his commitment to utopia, and more than a slight control freak, just like Monica. -

Kirinyaga es a la utopía y el postcolonialismo lo que Pío Moa a la Guerra Civil española. O como si César Vidal hubiesen escrito una novela de cf sobre el proceso independentista catalán.

No me ha gustado nada. Como novela de ciencia ficción sobre una utopía es un poco desastre, está claro que la palabra utopía lleva muchos años tirada en el barro, un término vacío que no significa ya nada, pero Resnick presenta la "utopía" más burda, menos currada y simplona que he leído en mucho tiempo, básicamente no se diferencia en nada de una secta. Y es simplona porque Resnick está más interesado en sermonear, así que nos presenta una serie de fabulillas o parábolas muy simples que en su mayoría versan sobre los conflictos entre las sagradas libertades individuales y la malvada opresión stalinista que impone la sociedad, lo cual nos dice bastante más de la ideología de Resnick que de los problemas de una hipotética utopía.

Por otro lado Resnick también se ocupa del poscolonialismo y le da unos palitos a la relatividad cultural. ¿Por qué elige a los kikuyu en vez de yo qué se, a los Amish? Porque lo que Resnick nos quiere contar a su simplona manera es que si África es un desastre es, como diría Macron, por problemas "civilizatorios", es decir, que las tribus africanas mientras sigan aferradas a sus bárbaras tradiciones (sacrificio de niños "hechiceros", ablación de clítoris, mujeres consideradas meras propiedades, etc) serán incapaces de gobernarse a sí mismas en paz y justicia. Ni la avanzada y superior influencia cultural, moral y tecnológica europea ha sido capaz de levantar aquello, fíjense como será la cosa. A ver, que en parte puede tener razón, pero este análisis tan simplista de una situación enormemente compleja, obviando los enormes problemas que ha causado el colonialismo (por no hablar de otros problemas geográficos, sociales, económicos, etc) hace que le asome tanto la patita que no hay por donde cogerlo.

Finalmente, en lo literario y atendiendo a su carácter de parábolas, la obra resulta francamente repetitiva y aburrida tras leer las dos o tres primeras historias. Se nos narra la historia desde el punto de vista del Amado Líder, un fanático manipulador que no duda en sacrificar la felicidad y bienestar de sus compatriotas de asteroide en aras de la pureza ideológica de su visión y que ya en el segundo relato empieza sacrificando a un bebé que ha nacido "de pie", para que nos vaya quedando claro el asunto. El desarrollo de todos los cuentos es igual, se introduce el conflicto (ya digo que casi siempre de libertad individual más relacionado con la idiosincrasia kikuyu que con los problemas de una hipotética sociedad utópica), se pegan unas batallas dialécticas en plan diálogos socráticos, como los personajes de las Fundaciones de Asimov o los rollacos libertarios de los pestiños de Heinlein, a ver quien tiene razón, se cuentan unas parábolas que me he acabado saltando de puro pesadas, el Amado Líder soluciona la papeleta con otro diálogo ingenioso y salva el día. Pero ojocuidao, van apareciendo grietas en el Paraíso hasta que la cosa no da para más, y es que, ¿quién se hubiera imaginado que una minúscula sociedad atrasada y aislada en el vacío del espacio podría fracasar sin cambio y evolución? Pues esta es la perogrullada que nos queda tras diez millones de relatos todos iguales machacando una y otra vez el mismo tema y que me ha costado horrores acabar. -

Kirinyaga is a collection of inter-related short stories that center around a terraformed planet designed to be the new home of the Kikuyu tribe of Africa, where they can live their lives in the old, traditional way, without interference from modern society.

I almost stopped reading this book 2 chapters (stories, technically) into it. Two main reasons for this:

1- I really dislike parables. They are usually obvious, simplistic, and preachy.

2- I intensely dislike Koriba, the main character.

Pressing on, because I really did want to give this one a chance, I did come to see that the parables tied into the story, and it made sense. I still felt that they were obvious, simplistic, and preachy, but there was a kind of layering there that helped make them bearable within the stories.

The stories themselves were quite repetitive, and I felt that the outcome for Kirinyaga was pretty obvious right from the start. It was just how it would get there that was in question.

Coming back to Koriba... Ugh. Where to start? He's highly idealistic, a Type A personality. Hypocritical, uncompromising, hard to sympathize with, and manipulative, but very clever. I feel like I would have enjoyed this story much more if I had been able to identify with Koriba. I understand the desire to maintain tradition and culture, but the way that he went about it was so wrong to me, that every time I would start to feel a shred of agreement with him, he'd up the ante and I'd retreat again.

His ideal is rigidly maintaining the traditional Kikuyu lifestyle, as interpreted and controlled by himself, and never, ever deviating, even the slightest bit. No matter the cost. If people suffer, they suffer. If they die, they die. That's the Kikuyu way. It was disgusting to see the extents that he would go to to prove his point.

I just couldn't understand him. Not at all. I'm a fan of compromise, but he sees life in stark black and white terms. He's very much a fan of the "You're either with me or against me" line. There is no middle ground, no room for anyone else to think or want anything, because all that matters to Koriba is what he thinks and wants for Kirinyaga and for himself, as the self-proclaimed "last true Kikuyu". He pulls the strings, and keeps the rest of the people ignorant and superstitiously fearful, thinking that that's the only way to form a Kikuyu Utopia.

Perhaps if the story had been told from the perspective of a new inhabitant of Kirinyaga, trying to adapt, or even from Koriba's trainee, I would have liked it better. As it is, I think it was interesting, but could have been shorter, and it definitely made me think. -

Vaig conèixer en Mike Resnick a la Catcon de Vilanova del 2017. L'Emilio Bueso i jo vam poder xerrar una estoneta, però ell estava força cansat. Em va fer la impressió d'un home afable, molt humil (molt) a pesar del palmarés de premis que té a la seva brillantíssima trajectoria. I m'avergonyeix reconèixer que no n'havia llegit res abans.

Afortunadament, em va signar aquest Kirinyaga que ara conservo com una joia a la meva prestatgeria. Per fi he trobat el moment de dedicar-li el temps que es mereixia.

I quin temps.

Darrera d'una prosa aparentment senzilla s'hi amaga un niu de saviesa. Que collons s'hi amaga: s'hi exibeix.

Si bé la història comença com un aplec de relats més o menys autònoms i fa la sensació que hi haurà una certa reiteració en l'esquema i estructura de cadascun d'ells, cal tenir en compte que el conjunt acaba evolucionant com una novel·la homogènia.

Per aquesta raó, recomano llegir l'epíleg a mode de"justificació" del mateix Resnick després de la quarta història. Aquests primers quatre contes són els més independents i poden causar estranyesa per la presència d'un narrador detestable i fanàtic. Són contes fabulosos però que poden provocar rebuig. Si en llegiu l'epíleg immediatament després, veureu com els raona Resnick i com els defensa, però alhora descobrireu com les crítiques sí que influeixen en certa manera en les següents històries, que acaben agafant un petit fil argumental interessantissím.

El volum es tanca amb una novel·leta curta, "Kilimanjaro", que dona una visió complementària a "Kirinyaga" i és pròpia d'un autor amb un coneixement immens de l'ànima humana. -

9/10

Muy interesante. No le cae el 10 por algún momento demasiado repetitivo, pero este autor consigue emocionarme siempre.

http://dreamsofelvex.blogspot.com/201... -

Quite by accident, I've been reading a lot of stories about righteous people who do wrong things for what they believe are right reasons. Some of these people reap the consequences of their decisions, and some do not. Some see the error of their choices, and a very few go on blindly believing that nobody else really understands, only they can see that they are right, and only they are able to interpret what is true.

The religion of my childhood referred to itself as "The Truth." As a child, I trusted in everything that implied, up to and including believing that there could be only one truth, and not realizing that there are many such groups who call themselves by those precise words.

In "The Truth," there are many rules, and the less thinking one does, the more following is possible. People act like they are happy when they choose not to think. But the truth is not "The Truth," and acting is not the same as being. Among the many rules in my particular "Truth," were rules regarding whom could teach, and whom could lead. There were rules governing relationships, permitted and proscribed activities, gender roles, clothing, and possessions, just as there is conformism in every society, to a greater or lesser degree. In my "Truth," to the greater degree, there were also rules regarding treatment of those who did not keep to the other rules, as well as instruction to repudiate any succumbed to "independent thinking."

Koriba, the mundumugu - a witch doctor and spiritual counselor - tries to hold his people, in the Utopia he helped to create, to unreasoning rules and tradition which do not allow for personal growth and change, and prevent cultural progress. His reasons are clearly in protection of what he thinks is perfect justice and ideal society, but he forgets to love the people in loving the ideas. The stories are brilliant in their execution.

These stories hurt my heart, but they are cathartic too. I lived in my own Kirinyaga. I know what it means to walk to Haven. -

A quien diga que no se puede innovar en la ciencia ficción le plantáis un Kirinyaga delante de las narices. No estamos hablando de una obra rompedora ni visionaria, pero sí de unos relatos planteados como parábolas de una parábola (la ciencia ficción no deja de ser eso, una parábola de la sociedad) sobre la identidad y su pérdida, las tradiciones, la homogenización, las tradiciones y los fanatismos. Una obra artesanal, escrita con mucho cariño y precisa como un reloj atómico.

-

Se hace un poco repetitiva, sobre todo teniendo en cuenta que las ideas principales se ven bastante claras en los dos primeros relatos. Aún así, me ha parecido muy interesante todo lo que transmite Resnick en este compedio de relatos y el personaje de Koriba me parece fascinante.

-

Un libro genial, aunque públicado en su día como relatos sueltos la historia se va siguiendo. En un futuro tras crear varios mundos habitables una comunidad keniana solicita uno de los mundos para crear una utopía viviendo de forma tradicional como antes de que llegase el hombre blanco.

Los relatos confrontan las tradiciones y plantean situaciones de difícil solución si se quiere mantener un estilo de vida sin cambios, sanidad, educación, derechos de la mujer, etc. Me resulta curioso como, de hecho hay una nota del autor, se le critico mucho al autor, incluso acusándole de machista, me recuerdo a las amenazas de muerte a actores por sus papeles en culebrones o cosas así.

El libro se lee rápido. Se incluye además un segundo relato largo, cuando los massais crean en otro mundo otra comunidad aunque aprendiendo de errores de los kikuyos o algo así se llaman los keniatas ancestrales.

Una interesante propuesta con relatos bastante buenos. -

I’m wavering between 4 and 5 stars. This was an extremely fascinating and throught-provoking story, or should I say collection of stories - or parables. “For I have Touched the Sky” moved me deeply, but not all stories were equally interesting or were as strong as that. Together all of them formed a tale of a man with a vision of a utopia, and his struggle against progress in the name of maintaining his dream. It’s both sympathetic and provocative and you should experience it.

-

Yes, yet another Resnick review from me. Before I get to the actual review, let me answer the inevitable resounding "Whys?" echoing from my many readers (2, 3? I've lost count, time for another census). I started reading Resnick for two reasons: 1) because after hearing he was a huge Africa fan who used his African experiences in his stories, I looked him up, noted our mutual interest in Africa and crosscultural writing, and I got an email a few days later with a buttload (yes, that is an actual unit of measurement) of attachments of his Africa short stories, all of which were featured in major publications and all of which were either nominated for or had won awards. 2) because he is the most published and awarded SF writer ever. 3) because once I read one of his books, I got hooked. His prose style is similar to mine (yeah, right, as if mine were this good), and I love the way he writes powerful characters and situations and lets the questions fly out of what develops. Also, whether or not they are answered is up to the reader.

So, that's why more Resnick, and I am not done yet, but will be taking at least a one book pause to read my buddy Ken Scholes' "Antiphon," a) because I have a copy a month ahead of its actual publication date; b) because I promised to not only review it but participate in discussions with a readers' group; and c) because I have been begging him for an early copy for a year since finishing the second in the series because the series is so freaking awesome, it's painful to have to wait. In fact, sidebar, if he could have just had the decency to put those twins off until he finished the series, he could have taken a nice break from writing without so cruelly abandoning his fans.

Okay, enough Resnick-Scholes ranting. Here's the review:

Kirinyaga is the most award-winning science fiction novel ever. Some call it a collection of stories, because Resnick wrote the chapters as short stories, sold them, won awards on them, and then assembled the book, but since together they create a coherent whole, I disagree with that assessment. This is a novel, and no one story would truly be complete without the others.

Kirinyaga tells the story of Koriba, a well intentioned Kikuyu man from Kenya who sets about to lead his people to set up their own traditional Utopia, a planet named Kirinyaga after the holy mountain of their god, Ngai, on Kenya. The goal of the settlers is to live the way their ancient ancestors lived with no European influence or niceties. They will hunt and farm for their food, live off the land in traditional bomas (huts) and rule their society with the traditional councils of Elders advised by the mundumugu, Koriba.

The story is really one of the best of intentions gone awry. Koriba's desire is to preserve the sanctity of his people's ways, but as time goes on and the original settlers die or age, the new minds begin asking questions not easily answered. Things become even worse as his chosen successor is exposed to ideas through Koriba's own computer and begins questions Koriba's ideas and the ways of his people publicly, which leads others to do the same.

Watching his utopia unravel along with his influence, Koriba faces tough decisions and challenges about the future.

That's all I'll say to avoid spoilers for anyone who hasn't actually discovered this yet, but I will make some comments on Resnick's Africa stuff in general.

Of the African works by him I've read, this is the most blatant in adhering and examining their cultural traditions. In books like Inferno, Paradise, and Purgatory, Resnick used African history and a mix of traditions like metaphors to tell science fiction stories examining the larger human condition and particularly Westerner's attitudes and approaches to those of other cultures or worlds. In other stories and books, he has examined this from different angles, but in this case, he delves into African's own attitudes about their own worlds and traditions. The same questions and ideas which led to the real erosion of traditional African cultures arise again through these stories and lead the reader to examine why the erosion occurs in every culture and ask whether it's good or bad. The answers are never black and white, nor are they simple, but they are worth asking.

Resnick's prose is simple enough for even a ten-year-old to grasp, but the questions and ideas he posits with it are deeply rich and complex and may require several readings even for adults to unravel and fully fathom. I know I have been reading and rereading and plan to do so again, and if you want scifi that challenges your world view, asks questions, and teaches you while still entertaining, I highly recommend this stuff, because it will reward you greatly for the effort.

For what its worth... -

Este fix-up de Mike Resnick es una joya de la literatura utópica, y es al mismo tiempo una narración hilada a partir de una serie de cuentos que pretenden ir desglosando los entresijos de una utopía.

Sigue leyendo... -

Librazo

-

Mike Resnick's Kirinyaga is an example of how science fiction isn't necessarily a genre; it's just a setting. Kirinyaga is technically science fiction, because it involves colonizing another world (the eponymous planetoid Kirinyaga, named for the mountain upon which the god of the Kikuyu, Ngai, lives). However, Kirinyaga isn't about spaceships or combat with high-tech weaponry or vast, evil empires. It's a collection of fables, and an extremely well-written one at that.

The narrator of Kirinyaga is Koriba, the mundumugu of the Kikuyu people who choose to settle on Kirinyaga and attempt to create a utopian society. Koriba is the ultimate type of reactionary: he desires a return to a past that not even he, an old man, can recall. He wants to return to the ways of the Kikuyu's ancestors, ways that went virtually extinct by his lifetime (in the 22nd century).

Koriba's belief that any European influence is corrupting plays a major role in the conflicts throughout the ten stories in this book. As he explains it to the Kikuyu: "if you accept one European thing, soon they will insist you accept them all." This slippery slope argument is unsound, of course, but it's understandable why Koriba thinks this. He grew up in a Kenya dominated by European values, which have eroded his people's proud past. Yet in his attempt to create a utopia, Koriba so vehemently opposes change that he runs the risk of stagnation. In the end, Koriba comes to the realization that most would-be utopians have: achieving a utopia is impossible, because the conditions necessary for a utopia are insufficient to sustain the human spirit.

Kirinyaga is also the answer to the often-expressed desire to live in more pastoral times. Some people labour under the impression that there was, at some point in human history, a great Golden Age, where there was little suffering, there were plentiful crops, and there were prosperous people. The hardships and tribulations of the Kikuyu on Kirinyaga demonstrate that "simpler times" were not necessarily "better times" and bely Koriba's belief that European technology is the root of evil.

But if that's the case, does that mean that we must necessarily surrender our past traditions in order to survive? No. Part of Kirinyaga's failure owes to the fact that no matter how much you try, you can't turn back the clock. Having been exposed to European values once, there's no way to remove cultural contamination. Fleeing to another planet doesn't work as long as one maintains a connection to the outside world.

Utopia is an impossible dream, and striving for it is madness. As "The Lotus and the Spear" demonstrates, people require conflict and adversity in order to have meaningful lives. A life with conflict is not a utopia, yet a life without conflict has no meaning. Koriba has some very admirable qualities, including his obstinacy; unfortunately, his refusal to accept even a modicum of change means that he can't survive in an ever-changing world.

The brilliance of Resnick's stories isn't the moral, of course; that's old hat. Instead, it's the package. Each chapter is a fable, and there are even fables-within-the-fable that Koriba tells to his people. Just as Koriba's fables pass on his wisdom to the Kikuyu, Resnick's fables pass on his themes on utopia. You can't make everybody happy. And sometimes, gods die. Finally, humans always have to change and adapt, even if this creates conflict. But even that isn't a blank cheque for survival. There are no guarantees. -

This was the perfect Book Club book. I think that this is a book worth reading, discussing, and enjoying no matter what your genre preference is. It is a quick read, entertaining, well written, engaging, and thought-provoking. I am very impressed with this writer's talent.

I spent a good deal of the book frustrated or angry with the main character (who is telling the story from his own perspective) but I still couldn't put the book down. It was too fascinating! The picture of the society he drew was such an accurate portrayal of human nature.

This story is set in a future where humans have the ability to terraform "planetoids" in our solar system. There is a belt of "Utopian" worlds where different groups of people have a charter to develop their own Utopian society on a newly created world. In this book, the main character is the witch doctor for the Kikuyu, an ancient Kenyan tribe who have refuted all European inventions and influences to reclaim their lost culture and heritage. They are on their own world of Kirinyaga to create a Kikuyuan Utopia. You then have the anachronism of a space station in the sky, controlling the weather, and a population on the planet living without any modern comforts.

***Warning! Sad things happen to children and babies in this book due to the harshness of their living conditions, their religion, and the witch doctor's decisions. These were not at all graphic, they were dealt with matter-of-factly, I just have a hard time dealing with anything sad happening to little ones, even if it was a part of a normal life in our ancient history.

***Spoiler Alert***!

My favorite part of this story is when Ndemi finally stands up to Koriba and leaves him to get educated on earth so he can return to teach his people truth and knowledge instead of Koriba's lies. Their disagreement about the goodness/necessity of facts vs. fables was interesting. I also loved the ending. It was so poetic! It created a strong image in my mind that will be with me for a very long time.

My favorite theme of this book relates to the importance of change; and how the desire to maintain things in status quo leads to stagnation and death. I like the different things that the author pointed out about the idea and fable of Utopia.

Overall, this book was a really great read! I think it should be on our Highschoolers' required reading lists. It was that profound! A classic! -

This is a story of obsession. Koriba is the leader of a group of people who live on a planet terraformed to be like Africa and designated as a Kikuyu Utopia. Koriba detests the European culture that has taken over Kenya, and how the European and Kenyan cultures have overtaken the identity of the Kikuyu people.

His Utopia is established as a place for the Kikuyu people to return to their original culture and live in harmony with the land. He is their mundumugu, or witch doctor. He is their “teacher, and the custodian of the tribal customs”. He believes that any tiny change in their culture will lead to its eventual complete loss.

This book is in the formant of ten short stories that blend seamlessly into one complete story. The first two stories effectively describe his ferocious devotion to creating this utopia and keeping the culture pure. The rest of the stories show Koriba’s continued struggles as different things challenge him, and the gradual changes in Koriba and his people.

I love stories that make you think, and this one does. I love it when a book can ask questions without any obvious preaching or explaining and this book succeeds. My favorite quotes from this book are things that characters actually said.

Change:

"All living things change... they change or they die."

“You can direct change Koriba… but you cannot prevent it.”

Meaning of Utopia:

“No one is suggesting that we don’t want to live in a Utopia, Koriba,” interjected Sannaka, “But the time has passed when you and you alone shall be the sole judge of what constitutes a Utopia.”

“Perhaps there are no Utopias, and we must each be concerned with our own happiness.”

It’s also about control:

“You are not an evil man, Koriba,” She said solemnly, “but you are wrong.”

“If that is so, then I shall have to live with it,” I said.

“But you are asking me to live with it…”

“It was you who taught me to think, Koriba… Would you have me stop thinking now, just because I think differently than you do?”

I am sure you can tell that I loved this book. It was so interesting, the plot moved quickly, and the characters and situations felt very real. This one goes right on my favorites list! -

I would rate Mike Resnick as not only a master storyteller, but also a master of the parable. While on the surface this is the story of Koriba, the witchdoctor, or Mundumugu of his tribe, the Kikuyu. This is a couple centuries in the future when Koriba has the will to get a planet terraformed so that his people can emigrate from the disgustingness that is Kenya with all its European influences and get back to the traditional soil-tilling, mud-hut living past that is the right of his people. So onto Kirinyaga they settle to create their Utopia.

But the magic of the story isn't that idea, but it is the question of what a utopia really is and can a society exist without external influence, without growth and progress, and without conflict. In parable after parable, underwriting the fable of each chapter Resnick explores these ideas through his obstinate protagonist. Koriba never changes and he never wants to change and thus he is an odd choice for the narrator, but it works because only through the eyes of a true believer can we, the readers, experience the changes and growth happening around him. He does become sympathetic just as he's caught in events he can't control while still being the most powerful member of his society. He teaches his people so much, but the one thing he doesn't teach them - independence - is the one thing that he is trying to hold back and his only non-Kikuyu parable, his only internal European influence, is that of the Dutch boy with his finger in the dike holding back the flood of change. He is Kikuyu, but he might be the only one left.

I recommend this book and its morals for anyone who wants to think about what they've read for days afterward. It's such a simple story and yet it's filled with layers of complexity that could take a lifetime to grasp. -

Utopia, a European concept that never works anywhere.

A Kikuyu man, Koriba, takes tribe members to a space colony he names after the sacred mountain Kirinyaga. A string of episodes of his life and the life of the colony ensue.

He is the Voice Of N'aga, the old God, he is the supreme authority on how these people must live their lives - old traditions rule, nothing new is accepted.

Which means he becomes a tyrant in the name of what he believes is right, but there is no way to put a society into a capsule and prevent it from growing and changing. One thing I've marveled at is how different cultures discover the same thing at the same time - so the use of clay vessels is universal - even if the cultures never came in contact with one another.

Luckily for the inhabitants of Kirinyaga - life is allowed to grow, develop and change, for Koriba things don't work out well. The inability to accept change make him a bitter old man.

Change isn't easy, it's not always good, but it always happens, accepting that and incorporating it into life is what makes us humans. -

I'm writing this review because Kirinyaga came up in the recent SFWA kerfuffle. First, Kirinyaga is not sexist. I am a feminist myself, and I consider it profoundly feminist. And yes, it's true that many African traditions are not only sexist but truly horrifying for women. Perhaps African female genital mutilation which predates Islam has slipped the minds of Resnick's critics. The Kikuyu practice FGM though it has been decreasing. I also want to say this: There are also many wonderful African traditions that should be preserved. Kirinyaga may not tell the whole story of who the Kikuyu are or have been in the past. No book ever does tell the whole story about any topic. It should inspire you to read more as many readers of Kirinyaga have done. I am one of them. I became interested in reading more about African cultures because I read Kirinyaga.

-

The story follows Koriba who leaves Kenya because it has become polluted and overcrowded but most of all European. He petitions the government to terraform a planetoid where he can take willing Kikuyus and live there as their ancestors had lived. Very thought provoking! What is "utopia"? Can there be balance between traditional culture and modern culture....can they coexist? Must one be sacrificed for the other? I think culture is supposed to evolve, by how much...or how far I'm not sure. The only thing that is constant is change.

-

This book is the Victor/Victoria of Utopian novels. The author is a white, American man writing from the perspective of a black, African man who's trying to rid his culture of all white, European influences.

It's also a damn good read. The flow and pacing are excellent. And there are stories within the story, numerous parables told in every chapter. And somehow, the protagonist ends up being frustrating and sympathetic at the same time.

A well-crafted an interesting take on the challenges inherent in constructing a culture-conscious Utopia. -

Odlicne price, vecinu sam procitao prije u prijevodu, stoga sam sada odlucio procitati do kraja na eng, a neke sam i ponovio na eng For I touched the Sky, recimo. Mozda najdraza iz zbirke

-

Libro que se lee muy bien.

Cada capítulo sigue un esquema parecido donde cuentan una parábola que luego tiene su reflejo en lo que ocurre en la historia. Plantea un problema moral y aplica la solución según dicta la tradición del pueblo.

Como dicen en el prólogo la prosa tiene un aire de sencillez muy a lo Asimov pero en cuanto a temática lo pondría más cercano a algunas historias de Ursula K. Le Guin.

En las reseñas que he encontrado en la web pero hablan de la utopía, ciencia ficción sociológica,… pero no he sido capaz de encontrar que traten el que para mi es el tema principal del libro. El aislacionismo. Los problemas que plantea una sociedad aislada y que se autoimpone además ser estática. Tenemos ejemplos claros relativamente recientes como la época de la URSS, Cuba o Corea del Norte donde, ya sea desde el interior o debido a elementos externos, la sociedad queda aislada y eso plantea unos problemas de difícil solución. Creo que hay muchos paralelismos ya sean buscados o que surgen al tratar de explicar cómo funciona una sociedad así.

Luego está la particularidad de esta utopía descrita en el libro donde hay una clara dependencia de un líder lo que hace que se profundice todavía más en la temática del aislamiento llevándola a nivel individual. El apartarse de la sociedad y ser un guía que exige el mantener las tradiciones aunque sea por imposición acercándose al despotismo de “todo por el pueblo pero sin el pueblo”. Y en esa exigencia llegamos a otro punto que también tiene muchas semejanzas con el mundo real donde en movimientos sociales se exige una integración o pertenencia total (no se puede ser un auténtico X si no estás a favor de Z y en contra de Y). El nivel de pureza.

Es un libro con varias capas y que las muestra con mucha naturalidad sin tratar de esconderlas.

En esta edición del libro hay después otro relato de temática similar pero es olvidable. Donde en el anterior había cierta sutileza y retórica al exponer las cosas en este es burdo y exagerado. El primero es como si fuese desnudo por la calle todo tranquilo y comentasen que está desnudo y responde que sí, que vale. El segundo es la misma situación pero ir gritando ¡Miradme, miradme!