| Title | : | The Lost Library: Gay Fiction Rediscovered |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 097146863X |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780971468634 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 232 |

| Publication | : | First published March 1, 2010 |

| Awards | : | San Francisco Book Festival Gay (2010) |

The Lost Library: Gay Fiction Rediscovered Reviews

-

The besetting sin of middle age is to discount the present in praise of the past. It's June in San Francisco, the streets are lined with rainbow flags, the Castro is now "historic" – and I catch myself thinking, Hell, I remember when pride parades were not only parties but raw, wild and militant. Before AIDS, when no one wanted to join the military or get married. (Then comes the after-voice: shut up, old man.)

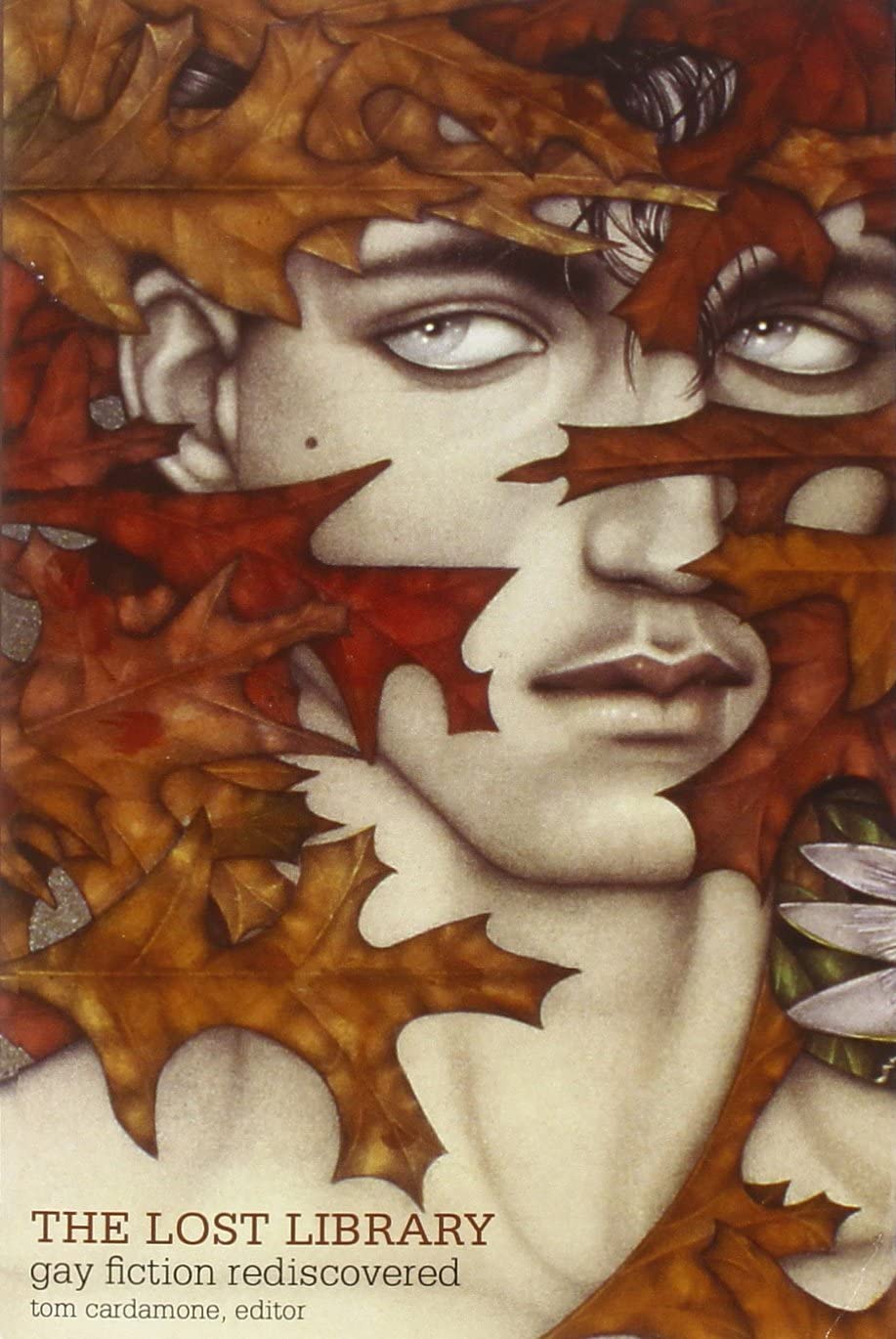

I mention this only because today I came across Cardamone's little book by chance in the local public library where a friend works, and immediately lost myself among its chapters, recalling books I read decades ago. And how perfect that its cover art is by

Mel Odom, whose work adorned so many of these forgotten classics.

I don't know if this book would appeal to anyone who's not bookish, gay and middle-aged but if you fall into this niche, it's an unexpected treasure: authors writing about the authors who inspired them, who initiated them into a life we'd barely dreamed of. For example, I remember sitting in the back of class in high school, hiding the book I was reading with a textbook – John Donovan's young adult novel from 1969,

I'll Get There. It Better Be Worth the Trip. – and coming upon the climactic scene (it's not much: only a kiss between two boys) with a shock. Martin Wilson's chapter here brought that moment back.

So many other strong emotions recalled: Jameson Currier's chapter on Christopher Coe's lucent

Such Times; the sharp grief of those years is sealed within its pages, when beautiful young men turned into dying old men within the space of months. Coe had died the month I bought the paperback. Buried among this list of books is a list of authors gone, far too young. I remember reading books by

Robert Ferro and

George Whitmore as soon as they appeared; I remember when they died.

Of course, one of the pleasures of lists is the way they evoke our own. As I ranged through the pages of The Lost Library, I wondered: What about

Splendora? Or the wickedly pseudonymous cheap paperback

The Story of Harold? Or Reynaud Camus' classically French

Tricks: 25 Encounters which in 1981 outed me to my Christian cousin who could not comprehend a book about serial "encounters" described in anatomical detail. Or the books by the gentle, wryly intelligent Bo Huston, whom I met in San Francisco the year I arrived? – Not to worry: these and worthy companions are all in another list at the end of the book. There's only one I thought of (in the course of writing this review) that isn't mentioned, maybe because it's not by a gay writer, but its protagonist is one of the most charming characters I've ever encountered –

Landscape with Traveler: The Pillow Book of Francis Reeves.

I rarely read "gay fiction" any more, and I suspect most gay authors would prefer not to be pigeon-holed. That battle is won. The world has changed for better and worse. Cardamone and his collaborators return us to another place and time with its promiscuous pleasures and sorrow. As a character in Coe's book remarks, "I really do find it hard to believe that there used to be such times." So do I, and I lived them. -

Wow, what a fantastic tribute to the power of literature to broaden people’s minds and to inspire and change lives.

What struck me again and again was how so many of these gay authors, writing about literature that had a seminal impact on them, recounted how encountering a specific book in a bookshop, library or even garage sale at a specific time had a crucial effect on their socio-sexual development and identity.

I wonder if this is something we have lost in the age of ebooks: that sense of walking into a library or bookshop, the smell of the stacks, the reverent silence, and the incredible sense of discovery and empowerment when you find a particular book that seems to speak to you directly in a language you understand.

Of course, ebooks have also revolutionised both publishing and reading in that a lot of out-of-print titles can be revived economically for a new generation of readers. The Lost Library clearly represents a vanguard of this movement.

Indeed, the book ends with Philip Clark’s ‘A History of the Reprinting of Gay Novels’, which recounts how specialist presses and dedicated small publishers have revived some of the out-of-print authors celebrated in Cardamone’s book.

What also struck me was the incredible depth and range of gay literature. I was astounded to learn that “travel writer Bayard Taylor’s Joseph and His Friend (1870) is generally considered the earliest example of a consciously gay novel.”

Many of the themes we take so for granted today, such as the coming-out novel, were pioneered by writers who were generally well ahead of their time, and who wrote and published in very difficult cultural and political climates. There were gay novels written in the time of WWII and the Vietnam War; the first YA novel saw the light of day in the 1960s.

This is by no means a comprehensive history of gaylit. What Cardamone does instead is stitch together a living document from other writers’ experiences and memories. This is an incredible read, alive and rich in the best possible way. May this book itself never be lost. -

A highly accessible must-read book for anyone interested in gay fiction. These essays shine a light on novels (and some story collections) published from the 1960's through the 1990's--all of it now out of print.

Each essay is an appreciation from a different writer about book with personal meaning for him. Christopher Bram tells about his friendship with Allan Barnett and his admiration for Barnett's story collection "The Body and Its Dangers"... Aaron Hamburger writes about his missed connection with reclusive author J.S. Marcus in Berlin, the setting for Marcus's novel "The Captain's Fire"... Editor Tom Cardamone writes about the bond he felt with "The Sacred Lips of The Bronx," Doug Sadownick's novel in which a grown man looks back on his first love--and how that bond helped him come out.

Fiction's power to bring readers into a deeper relationship with the self is an undercurrent of this entire collection. But its true significance will be as an important, if highly personalized, addition to the scholarship of the often misunderstood and maligned term "gay fiction." -

(Original review is here:

http://andyquan.com/?p=65)

Books are years in the making, and it was a few years ago that Tom Cardamone, asked whether I’d be interested in contributing an essay to a collection about favourite gay books that were out-of-print. Tom and I had connected with each other through a tenuous link or two. He had written a positive review of my collection of sex fiction, but he’d also done a review of a book that I was also about to review for an internet magazine. I asked him whether he’d have a look at it.

This explanation may seem unnecessary, but it is as an example of how people connect with each other, across space and time, and form bonds and sometimes community. To be honest, while I immediately thought of a book I could write about, I wasn’t so sure about the concept of the anthology. Was it sellable? Would it be interesting? It seemed somehow obscure to me, gay writers writing about books no longer available. The point being? Was it to capture something lost? Try to get the books republished? Or simply a historical document?

To counter the possibility of the book being too academic, too esoteric, I wrote my essay with a particular intent – I would talk about why the book appealed to me in an accessible way, how it related to my journey as a gay man and a writer, and knowing that others may not possibly ever read it, demonstrate a bit of the book’s beauty (My choice was Patrick Roscoe’s “Birthmarks”. Ironically, when I sent him a fan e-mail telling him I’d be highlighting his book, he responded with anger about how the publisher had ruined it from his original intent.)

I was amused on reading the finally-published book, in a beautiful edition by Haiduk Press – gorgeous cover and a delicious feel to the pages – that this was the approach taken by most contributors, and that the collection is not obscure, but an interesting and unique approach to gay history and gay men’s lives featuring engaging and lively prose about something we love and why we loved it. As much as literary merit, the books featured in this anthology, pointed ways for gay men to survive, live and love, gave hope and possibility, and told us that we were not alone.

It was a fascinating social history to discover so many works with gay content written at times with so much gay oppression, whether a 1924 novel by Glenway Westcott, or young adult novels from 1969 and 1972. The breadth of the collection (there are 28 essays in all) spans a long period of gay history. Many of the early books reviewed featured rich, older gay men with much younger lovers, living in high society in New York or in European cities, some involved with hustlers; this was followed by an exploration of the many novels to come out of the early years of the AIDS epidemic. Another major strand is about gay men looking for and finding themselves (or who they hoped to be) whether in more recent novels featuring black gay characters, awkward gay teenagers, or men facing oppression, or in love, or at play.

I found it interesting how often contributors knew the authors of the books they wrote about, as friends and colleagues, or perhaps because they’d tracked them down as fans: a comment both on how small the gay literary world is but also how emotional ties affect how we view art. Rather than making the book feel like a club of insiders though, I think this aspect of the book spoke well to how we make connections and community and friendships.

I was also struck by a common tone of nostalgia and regret. It makes sense. After all, this book is called the “lost library”, it is about books that are no longer available, that the contributors long to see in print again, or perhaps that their authors were still alive. At the same time, it is a meeting of writers, who are often in the trade of capturing memories and romanticizing the past, and gay sensibility, which often is about wanting to be someone else or wanting to be a better self, or feeling “special” or “different” and turning that uniqueness to advantage. Bill Brent quotes an unpublished passage by Paul Reed about a man who spends so much time longing for his past that he turned regret into an artform.

Even if this melancholy doesn’t appeal to you, I think any gay man interested in gay identity and history will find “The Lost Library” engaging, be swept into conversations about why and how we love men, the moments we knew we were gay, the realizations that life would be just fine, and the signposts, in the form of books, that showed us the way. Not only about books, this anthology has fine writing in it, which makes a good tribute to the gay writers featured. -

This is a lovely collection of essays by gay male writers about now out-of-print books by their forebears that particularly affected them in some way. Many of these essays are in themselves beautiful writing and my “To-Read” list has expanded accordingly. I particularly want to get my hands on George Whitmore’s Nebraska, Mark Merlis’s American Studies (which is happily back in print now) and Time Remaining by James McCourt, after reading the respective paeans to them here. There is also a palpable melancholy transmitted in this tome – a realization that the vast majority of writing captured in the “permanent” form of published books is soon cast away onto shelves to gather dust, lost and forgotten to the ravages of time. I have to say I was disappointed that my personal favorite “lost” classic, The Story of Harold by Terry Andrews (aka George Selden) from 1974 did not get an essay here but was pleased to see it listed in the “Of Further Interest” section in the back - I cannot recommend this amazing book highly enough to lovers of gay fiction! At any rate, kudos to Editor Tom Cardamone for pulling this off so well and with so much love and care – maybe there will be a sequel?

-

ESSAYS ON OUT-OF-PRINT GAY FICTION

I discovered The Lost Library: Gay Fiction Rediscovered in Giovanni’s Room in Philadelphia soon after it was published in 2010. The beautiful cover art by Mel Odom caught my attention. I’ll pick up any book with a Mel Odom cover. I scanned the table of contents which listed twenty-eight essays by prominent gay writers on twenty-eight out-of-print gay novels and short story collections. Several of the essays were about favorite books of mine, other essays were about books that I had never gotten around to read, and several of the essays were about books I didn’t know. I have consulted The Lost Library many times during the past decade. My copy has become somewhat worn.

In the first essay in The Lost Library, Michael Graves discusses Rabih Alameddine’s The Perv: Stories (1999). Graves says that Alameddine inspired him as a writer: “Be gallant. Be yourself. Create without a filter. Create without fear.” The essayists in The Lost Library have taken Graves’s words of wisdom to heart. They treat the subjects of their essays with extreme gallantry. They exhibit remarkable candor when they relate how they found the books about which they write and what the books mean to them. I’m sure that the provocative and pioneering writers who are subjects of the essays had to overcome a great deal of fear in order to create their books without filters.

Tom Cardamone, the editor of The Lost Library, was inspired in his decision to let the contributors choose the books and authors about which they wanted to write. The coupling of essayists with authors is intriguing, for instance, Jameson Currier on Christopher Coe, Jonathan Harper on Richard Hall, Philip Gambone on Donald Wildham, and Christopher Bram on Allen Barnett. Each essayist captures the essence of his subject book in just a few words. Gregory Woods writes that in Roger Peyrefitte’s The Exile of Capri (1961), ‘no reputation is undamaged.” Bill Brent succinctly describes Paul Reed’s Longing (1988) as being about “psychic survival in hard times.” Timothy Young in his essay on James McCourt’s Time Remaining (1993) makes the campy yet poignant observation that “straights obsess about murder; fags about loss.”

As I mentioned above, the cover of a book can influence a prospective reader to pick up a book. Many of the essayists in The Lost Library attest to this. I bought Music I Never Dreamed Of (1989) by John Gilgun solely for the cover. I knew nothing about the book or the author, but since that serendipitous moment in the used book section at Philly AIDS Thrift at Giovanni’s Room when I discovered this book, Music I Never Dreamed Of has become one of my all-time favorite gay novels. If there is a gay literary canon, John Gilgun’s Music I Never Dreamed Of has a prominent place in it.

In his essay on Music I Never Dreamed Of for The Lost Library, Wayne Courtois writes that he set out to write “a conventional critical” essay ,“ but, instead, he wrote “a series of [unconventional] impressionistic pieces that [he hopes] will magically coalesce in the mind of the reader into some kind of magnificent whole.” Gilgun’s novel is undeniably magical and magnificent, while at the same time, as Courtois emphasizes, it teems with “gritty realism.” Stevie Riley, the engaging nineteen-year-old narrator, battles his restrictive Irish Catholic family and vows to get out of South Boston. Courtois is right on when he describes Stevie as “gloriously alive.” Stevie is going to go out there and find himself. I identify with Stevie when he faces a dilemma in 1954 that I faced in 1966: Should I check the box?

Most of my four years in the Navy (1966-1969)—I didn’t check the box—were spent in Vietnam. During the 1980s, when it seemed as if a new novel about the Vietnam War came out every month, I masochistically grabbed each one and devoured it. I had no idea what I was in for when I bought the paperback of The Boy Who Picked the Bullets Up (1981) by Charles Nelson. I had heard rumors that it had gay content. Jim Marks makes a surprising and daring choice to write about Nelson’s epistolary novel. Marks observes: “This gay Vietnam novel is pretty much sui generis.” His no-nonsense essay is conventional literary criticism compared to Wayne Courtois’s impressionistic piece on Music I Never Dreamed Of. Marks expertly places The Boy Who Picked the Bullets Up in relation to the fucked-up America that paved the road to hell that Kurt Strom, a gay medic, experiences in Vietnam. According to Marks, “For those of us who came of age in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, the Vietnam War was the central precipitating national crisis of our lives.” I agree with Marks. My experiences in Vietnam were not remotely comparable to Kurt Strom’s, but not a day in my life goes by that I don’t think about them.

Rich Whitaker’s essay on the late Mark Merlis’s American Studies (1994) is respectful and reverent. Whitaker insightfully writes: “The tension between sordid—but potentially ‘sacred’—contact and lonely (but elegant) solitude is the overriding preoccupation of Merlis’s rigorous, irrepressible American Studies.” Merlis was unique among gay novelists: He wrote about middle-aged gay men. The consensus of the members of a gay men’s book club to which I once belonged was that American Studies was the best book we had ever read. We must have identified with Reeve, the narrator of American Studies, as he recuperates in the hospital after a beating and lusts for the straight young man in the bed next to him. But much more goes on in the novel than this.

Whitaker’s essay on American Studies by Mark Merlis brought back delightful and sad memories to me. I became acquainted with Mark at Tavern in Camac in Philadelphia. While drinking white wine, we talked about books and writers. Occasionally, Mark would go up to the piano and sing an obscure Sondheim character song in his raspy voice. He tantalized me with tidbits about his new novel and even shared mockups of the jacket covers that were being considered by the publisher for the book. I don’t believe Mark’s favorite was chosen. JD, Mark’s last novel, was published in 2015. I was devastated when he told me that he had been diagnosed with ALS. Mark Merlis was a brave man who took no prisoners in his writing. The wrenching JD deserves more attention than it has received.

In 2010 at about the same time that The Lost Library was published, one of the books that was the subject of an essay in the book was brought back into print—in a fortieth anniversary edition, no less. This book is John Donovan’s groundbreaking young adult novel, I’ll Get There. It Better Be Worth the Trip (1969). Thirteen-year-old Davy Ross and his best friend, Fred, a dachshund, are wonderfully captivating characters. But this isn’t a typical boy and his dog story. In the early 1970s, I discovered the mass market paperback edition of I’ll Get There. It Better Be Worth the Trip. I was so overwhelmed and enthused by the little book that I pushed it on several co-workers and friends who loved it as much as I did. I was thrilled that Martin Wilson, the author of two fine young adult novels, contributes the essay for I’ll Get There. It Better Be Worth the Trip. Wilson writes that Donovan’s novel “was the first young adult novel to deal with homosexuality.” Donovan treats the relationship between Davy and Altschuler, a school jock, with superb nuance. Wilson also contributes another essay to the reissue of John Donovan’s pioneering work.

In his essay on Michael Grumley’s Life Drawing (1991), Sam J. Miller asks the question, “Why is this book out of print?” All the essayists in The Lost Library implicitly, if not explicitly, ask this question. ReQueered Tales recently reissued Life Drawing in an e-book edition.

What might a future edition of The Lost Library include? -

Coming out used to be much more difficult and was ripe with dangers that today’s gay youth are wholly unaware of. Tom Cardamone’s introduction in this homage to out of print gay fiction touches upon those challenges, and how once-upon-a-not-so-long-ago-time gay fiction and bookstores were the entry point for many to our community. Those days may have passed but the connection to our roots and our literature is just as strong—at least for some of us—than ever. Full disclosure, not only am I included in this collection, but I was involved with Tom from the time he originated the idea for this anthology through to the end in searching for just the right publisher; it was well worth his valiant effort. There is a lot to appreciate in this anthology, not only will it give you an idea of how broad the scope of gay lit is, as well as some worthy (albeit hard to find) books to add to your must read list, but it brings up the very real point of why fiction, especially gay fiction, is still relevant to our community; it unites us from one generation to the next as we pass down our stories of the trials faced and overcome (and the sex we had along the way). While some essays focus more on the books discussed and can read like reviews or literary criticism, what most endeared me are the very personal pieces that depict how a certain text came into the reader's life and how it may have impacted him, for good or ill, with some heart-wrenching honesty. This is a resource that should be in every gay reader’s library.

Read my essay about Lynn Hall's young adult novel, Sticks and Stones, in

VelvetMafia.com to whet your appetite for this excellent book about books. -

A concise history of 20th-century gay literature.

Most people could probably name one or two gay literary novels, if pressed. The essays in Cardamone's collection will introduce readers to many more. Each contributor examines his favorite gay novel at length, not just for literary quality/merit, but also in terms of the effect said text had on his own evolution/experience as a gay man.

I consider myself a fairly knowledgeable reader, but this book blew me away. 99% of the texts--to say nothing of the contributors--were unknown to me, so reading the collection was like getting a crash course in gay literature. These men and their writing were never mentioned at any time during any English course I ever took (not even at PhD level) and when I was coming up, there were no queer lit classes of any kind. You don't really get how erasure works until you've got its evidence in your hands. To supplement the excellent essays, the editor has included a list of the featured titles in chronological order, a contributors' section that leads to even more titles and websites of interest, and a bibliography of even MORE books to explore.

This is, in effect, an essential title for all medium-t0-large literature collections, to supplement the horrible gap that most of us have in our educations on this topic. I appreciate the Kutztown (PA) University Rohrback Library's willingness to lend it over to me, and when I get back to the office, I'll be putting in an order for this for our own literature collection. When you come across a book that demonstrates how ignorant you actually are, in your own specialization, you jump on that shit and make it right. -

Talk about a labor of love! These essays are great, well written by wonderful authors. I just wasn't in the mood for essays or I think I would have rated it higher. Biggest problem for me was that some of the novels reviewed were ones I read when published and that I didn't necessarily like at the time. There's only so much sex and drugs one can handle, and look where that's gotten us. So while there's sense in making beauty from horrible situations, after awhile it's no longer pretty or unique and it's just depressing. Don't get me wrong, I was inspired to order a few from alibris.com. It’s just that if I were to do it over again, I would have spread reading this out over a month or so instead of in a couple of days.

-

A dazzling and pioneering collection of essays by contemporary gay writers who remember — and memorialize — those literary works that shaped their own personal journeys toward self-recognition. Collectively, the essays testify to the enduring power of art to illuminate the paths that lead us home. . . . A major milestone in the on-going project of constructing a distinctly gay literary history.

-

Nice collection of essays by gay writers on more or less obscure gay books which they feel deserve more attention. In many cases the essayist rereads a book that was inflential on him when coming out. As someone who came out in the gay section of the library, I could relate.

-

The trouble with anthologies is that you only get what you know. I thought I am quite well read but apparently my reading goes as far as the Stonewall. So I need to study more classics. But this book is definitely a good start.

-

2010 Rainbow Awards Honorable Mention (5* from at least 1 judge)

-

haven't gotten yet but can't wait!