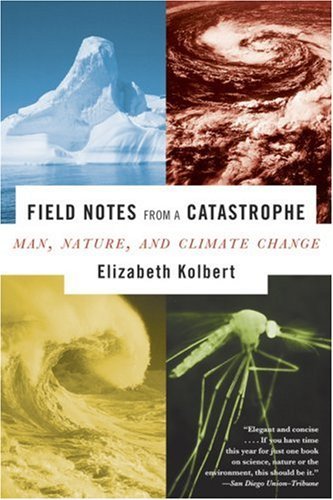

| Title | : | Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1596911301 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781596911307 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 225 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 2006 |

Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change Reviews

-

“As the effects of global warming become more and more difficult to ignore, will we react by finally fashioning a global response? Or will we retreat into ever narrower and more destructive forms of self-interest? It may seem impossible to imagine that a technologically advanced society could choose, in essence, to destroy itself, but that is what we are now in the process of doing"--Elizabeth Kohlbert, the concluding paragraph of this book, published in 2006.

This book, Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature and Climate Change by Elizabeth Kolbert, was (as I just said) published in 2006 (so know it is not precisely "up to date," but I have been slowly and painfully been reading The Uninhabitable Earth, by David Wallace-Wells, had some time in the car I could not read a physical book, so decided to listen an abridged version of this book (4½ hours) to see what came out of the dire warnings it gave us 15 years ago and kind of compare it in my head to what Wallace-Wells has to say. I had read when it came out the award-winning three-part series she wrote for The New Yorker, of which this book is an expansion.

The book’s primary audience is—I think—mild climate skeptics, maybe including some smart but right-wing politicians, or those just wanting to see just how serious this global warming stuff really might be. Kolbert, whose more recent book The Sixth Extinction I have also been reading but not yet reviewed, traveled to the melting Alaskan permafrost to talk with long time scientists about the effects of CO2 on global warming and her report is absolutely devastating, though she is an elegant writer in communicating the scientific facts and consensus on these issues. She, from my perspective, is not sensationalistic; she doesn’t engage in what some people deride as “climate change porn.” In giving a picture of her time, at the turn of the century, she also draws parallels to lost civilizations, and she clearly indicts Big Oil and Big Biz in especially the U. S. who have steered politicians into doing nothing about climate change, in spite of the direst warnings. Politicians we have elected and continue to re-elect. In the 2016 Presidential debates, there was not a single question directed to the candidates, not even on the political radar, the Kyoto and Paris accords genocidally ignored, so I already have a clear sense of where things have gone since then, but I just wanted to remind myself of the trajectory of events. I have kids. I teach. I am still alive and facing the future, though many fewer years than my past.

“We have to face the quantitative nature of the challenge,” he told me one day over lunch at the NYU faculty club. “Right now, we’re going to just burn everything up; we’re going to heat the atmosphere to the temperature it was in the Cretaceous, when there were crocodiles at the poles. And then everything will collapse.”

I repeat: This was written 15 years ago, when it was already the hottest time on record, and it has only gotten hotter each year. Trump, even worse than Bush, only turns back environmental protections, does nothing to address the crisis. And more than 40 % of the U.S. population as of today would still vote for him. Not a good sign for the planet. -

Elizabeth Kolbert was, still is I think, the main environmental writer for The New Yorker, though she writes of other things too, nowadays. This book was one of the first books I read on climate change, and is particularly convincing as it is based on actually observing what was going on in the Arctic, not on climate models, theoretical projections, or any such things as these (though I imagine that some of this stuff is mentioned in the book, I don't recall).

Kolbert is a fine writer, and although I suppose the book is somewhat out of date by now - the things she writes of have gone from bad to much worse - it is still a good introduction to climate change from the point of view of the Arctic, where things are changing fastest. -

This was more hard science than rhetoric which was welcome. Kolbert lays out the argument convincingly and compellingly. Because she is not daunted by the science, the argument comes across measured and deliberate - maybe even a bit understated at times - making it all the more effective. For anyone still harboring doubts about global warming, I'd like to think this book may well challenge their current thought processes.

Kolbert takes us on a voyage across Iceland and Greenland, glaciers in Alaska and more temperate zones in Western Europe to describe the already substantial effects of climate change. She claims, with admirable clarity, the consequences can already be felt on every continent, every country, by plants and animals alike. She also takes us on a brief history of the science of climate change and the political agendas that have followed.

There is the odd note of potential optimism towards the end. Overall, though, and especially if you read the edition with the updated 2009 afterword, you can't help but feel an overwhelming sense of despair, dread even, when you consider how little has been done to date and how very little is likely to be done in the near future to reduce the effects of global warming. It's abundantly clear there's no stopping it. -

This book, 'Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature and Climate Change' by Elizabeth Kolbert grew out of a three-part series she wrote for the 'New Yorker'. In this slim volume, Elizabeth Kolbert methodically explains the science of climate change and the warming temperatures of the earth. I think one of the most startling aspects of this book, for me, was learning that the study of climate change as it relates to the burning of fossil fuels actually dates back to the 19th century. This isn't new…

Ms. Kolbert starts with the history of the scientists who matter most in the study of the warming of the planet. The first scientist to make a contribution was an Irish physicist named John Tyndall. In the latter part of the 1850s, he began to study a variety of gases and is the person who identified what is now called the 'natural greenhouse effect'.

A Swedish chemist named Svante Arrhenius picked up the research where Tyndall left off. Arrhenius began painstakingly working out the effects of carbon dioxide (CO2) on global temperatures. He had been observing the rapid industrialization which was occurring across the world and began calculating how the earth's temperature would be affected by changing CO2 levels. Arrhenius recognized that industrialization and climate change were related and that the burning of fossil fuels over time would lead to the warming of the planet. He proposed an estimate of just how many years he thought it would take for this warming to occur…. he thought it would take 3,000 years of coal burning. Sadly and unfortunately, he was off in his calculations only by about 2,850 years.

Building on the science she provided, Elizabeth Kolbert then takes the reader on a journey with her to a number of places across the globe. She begins in the interior of Alaska, speaking with scientists about the thawing of the permafrost and how this is an indicator of global temperatures. She also travels to the ice sheets of Greenland and the jungles of Costa Rica… once again collecting data from scientists…. scientists who methodically describe the observations they have been making over time… painting a downright shocking picture of just how quickly the earth is warming and what the consequences will be for the many species who are on the brink of extinction and of course, for man and the world as we know it.

Although the information in this book is dated (the book was written almost a decade ago… which tells me that things are more dire than this book demonstrates!), I wanted to read it because it is an excellent source for understanding the science behind what has oddly become a controversial subject. This book was easy to understand … written in language which is highly accessible to people like me who are far from proficient in science.

If you have an interest in understanding this topic, I would highly recommend this book as a starting place.

My favorite quote…."It may seem impossible to imagine that a technologically advanced society could choose, in essence, to destroy itself , but that is now what we are in the process of doing." -

It’s impressive how well Kolbert avoids doom and gloom. Neither does she understate the issue. She navigates the polemic (that’s been made false polemic), debunks the myths, observes from ground zero, outlines plans of action. It’s an excellent primer, well-researched and grounded. But ultimately, yeah: this was written ten years ago and we’re still not paying attention. Soon what happens next won’t be up to us.

-

Field Notes from a Catastrophe was first published 2006 so it's 16 years old by now, and it does show. A lot of things have happened, and not so much has happened. It was an interesting read as one could expect from a book by Elizabeth Kolbert. She is a good writer. There is no doubt about that in my mind.

She is a journalist first, book writer second, and this book is very much a journalist book. Set up in a similar way as most journalist books are set up. We get to follow her as she goes around meeting people, taking trips with them, and watching them work. To me she is quite good at making these scenes very real. She is a good writer, and describes people, places, and events very well.

But this is a book based on science, and she also has a talent for making science understandable, which is the hallmark of a good science communicator. As depressing as our climate crisis is, I never felt this book was pessimistic. However, I still prefer her The Sixth Extinction because I think that was a book with bit stronger build up, and clearer concept. But Field Notes from a Catastrophe is well worth the read, even though it is 16 years old. -

The only thing more hope-killing than reading Elizabeth Kolbert on climate change see also

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History is reading one of her books several years after publication, knowing no progress has been made. What she writes is impossible to deny. This book was published before The Sixth Extinction, then re-issued in 2014 with a few updates that only confirm the bad tidings. Trying to sum up the book here I went back to what I said about Sixth Extinction. q.v. Though this book precedes it, the pair summed leave me in 20o18 in despair.

"Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch'intrate" -

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

― Upton Sinclair, I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked

That famous quote from Upton Sinclair seems highly appropriate to any discussion of climate change in this country. Entrenched, very powerful economic interests control our political system and, to a great extent, our media, and those interests are determined that business as usual shall prevail in the production and distribution of energy. In other words, petrochemical companies should be allowed to operate unchecked and unregulated. That this is a recipe for worldwide catastrophe is made quite clear in this slim book by science writer Elizabeth Kolbert.

Kolbert organizes her narrative as a series of travelogues to various parts of the world where the effects of global warming are made most evident. And so we visit the Alaskan interior, Iceland, and the Greenland ice sheet, as well as the mountains and meadows of Britain and Europe and the jungles of Costa Rica. We also get to meet the researchers in all these places who are working hard to understand the effects of a warming climate.

Kolbert also takes us back to the beginning of the study of climate and climate change in the 19th century where we meet Irish physicist John Tyndall who studied the absorptive properties of various gases and came up with the first accurate account of how the atmosphere functions.

We also meet Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius, who picked up where Tyndall left off and who later would win the Nobel Prize for his work on electrolytic dissociation. Arrhenius became curious about the effects of carbon dioxide on global temperatures. He was apparently interested in whether falling levels of carbon dioxide might have caused the ice ages. He calculated how the earth's temperature would be affected by changing carbon dioxide levels. He was able to declare that rising levels of carbon dioxide would allow future generations "to live under a warmer sky."

Kolbert reviews some of the cultures that have suffered from or been destroyed by climate change in the past - for example, the classical Mayan civilization of the Yucatan and, even earlier, that of Akkad between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers.

This is all fascinating stuff for those of us who are interested in this issue, an audience which should include the entire human race. The information is presented in a comprehensive and succinct manner and in highly readable form. Kolbert has a knack for making complicated topics understandable.

The book was first published in 2006 in the middle of the George W. Bush presidency and one of the saddest chapters of the book is entitled "The Day After Kyoto" which begins with a conversation with Bush's Under Secretary of State for Democracy and Global Affairs, Paula Dobriansky. Dobriansky attempts to explain and defend the adminstration's policy on climate change. What she actually does is repeat the same talking point over and over again.

Indeed, the history of the United States' handling of the problem of global warming has been mostly downhill since President George H.W. Bush acknowledged the problem and signed the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. It has mostly been a history of denial of basic science and a refusal to act or to lead, as perhaps best exemplified by climate change denialist Sen. James Inhofe of Oklahoma.

In an afterword written in January 2009, Kolbert makes clear that business as usual continues and without U.S. leadership the problem of climate change cannot be solved. It seems unlikely that that will happen in the foreseeable future. The warnings of scientists like James Hansen continue to go unheeded and Earth continues to heat up. I finished this book feeling very depressed about the future prospects for survival of the human race. -

Field Notes From A Catastrophe is an interesting book that calmly lays out the evidence to support the fact that the earth is now the warmest it has been in the past 420,000 years. She then goes on to talk about differing scientists viewpoints of what this might mean. At the core, all of the important scientists in the field agree that the warming means that the planet is on the edge of a major climate change. The main point of contention seems to be the time frame in which that will happen and how much longer we have before that outcome is irreversible.

Very nicely done without the alarmist tone that many writers on the subject develop (probably because the potential outcomes are alarming.) -

I read The Sixth Extinction a few months ago, so it was only right that I read Kolbert's summary of global warming and the American political system. Surprise surprise, the Bush Administration had no inclination to acknowledge global warming or the future of this planet. America isn't the only one, but it is (was) the leader that other nations looked to for guidance. I'm not at all surprised they bungled the snatch. I wish people would take this seriously. I very thought provoking read if you want a book on climate change.

-

The content is not uplifting, but this message needs to be heard.

-

Elizabeth Kolbert’s "Field Notes From a Catastrophe" is more than ten years old (I read the 2006 edition) but don’t let that dissuade you from reading this brisk, concise overview of climate change and all the reasons we should be worried.

Very worried.

Kolbert zooms in and zooms out, from details to big-picture analysis. She visits the Alaskan village of Shismaref five miles off the coast of the Seward Peninsula. She heads to Swiss Camp, a research station on a platform drilled into the Greenland ice sheet. And, among other locations, she takes a look at the Monteverde Cloud Forest in north-central Costa Rica. Everywhere she goes are clear-eyed scientists doing their thing—observing, monitoring, measuring. And watching the world change under the pressures of global warming.

Everywhere Kolbert stops, the signs of change are abundant, unequivocal, unambiguous—all without being sensational. We are sloppy drunk on fossil fuels and show no interest in sobering up. Kolbert’s writing is matter-of-fact, understated, and calm. Published the same year as Davis Guggenheim’s An Inconvenient Truth was released (based on Al Gore’s talks on climate change), Kolbert’s narrative sounds the alarm in no uncertain terms, but it’s hardly a diatribe. Bitterness is buried in the brutal facts.

What is worrisome is to read this and know the data have only grown worse over the last decade, particularly with deniers backed by the billionaires who crowd the Oval Office, the backwards-thinking head of the EPA who scrubbed the agency’s website of any mention of climate change, and many of their backers and political supporters. The cautionary mention in Field Notes about increasing hurricane strength—the book was finishing up around the time of Hurricane Katrina—comes across as tame and quaint in the wake of Harvey, Irma and Maria during 2017.

Recently (Nov. 2, 2017), 13 federal agencies unveiled an exhaustive scientific report that blamed humans as the dominant cause for creating the warmest period in the history of civilization. This “finding” is in direct conflict with the Trump administration’s position on climate change, but should we be encouraged by its publication? What will provoke our leaders to put some urgency behind the many steps that could be implemented to entice a new pattern of behavior and energy use?

It has been “business as usual,” for the most part, since Field Notes was published and Kolbert’s most devastating chapter underscores that even the introduction of various “stabilization wedges” won’t be easy to adopt. And might be too late, given the momentum that climate change has gained.

The "wedges" are things like solar power, wind power, nuclear power, cutting energy use in residential and commercial buildings by a quarter, or slashing automobile use in half and simultaneously doubling fuel efficiency. The “wedges” were developed by Robert Socolow, a professor of engineering at Princeton.

“All of Socolow’s calculations,” Kolbert writes, “are based on the notion—clearly hypothetical—that steps to stabilize emissions will be taken immediately, or at least within the next few years … The overriding message of Socolow’s wedges is that the longer we wait—and the more infrastructure we build without regard to its impact on emissions—the more daunting the task of keeping CO2 levels below 500 parts per million will become.” (We sailed right past 400 PPM last in March 2017).

Will we heat the atmosphere to the point where there are crocodiles at the poles, as there were in the Cretaceous? Seems like we’re headed there.

Maybe, if we can make "Field Notes" required reading in every high school today, we could begin to turn the trend around. Political pressure will be key to the pace at which we try to change our approach.

Right now, as Kolbert concludes, we are destroying ourselves. And doing precious little about it. -

In Field Notes from a Catastrophe, Kolbert goes to distant places and interviews scientists about what they’re doing. She covers many areas of research, including the melting permafrost, the melting glaciers, Hansen’s climate modelling, the northerly spread of insects, and more. In each case, she effectively summarizes how scientists gather data, how they interpret it, and she explains the implications of this research clearly. Better still, Field Notes is not only informative but is also very readable. Kolbert’s follow up, The Sixth Extinction, is the more lauded, but I found Field Notes better—of course, in making this comparison, I am really suggesting that everyone should read both. Recommended.

A side note. I'd had Field Notes from a Catastrophe on my shelf for some time now. Although it's short, which usually means read almost immediately, I had put off reading it because a) it was on my shelf and could wait while I worked through library books that came with deadlines and b) it was published in 2006 and would probably be dated. Well, I was wrong. -

Prior to reading this I had read The Weather Makers by Tim Flannery. It was an excellent book full of scientific explanations to nearly all the questions I had about the issue of climate change. Field Notes From a Catastrophe by Elizabeth Kolbert is also an excellent book. In fact, I wish I had read it first - not because it is the better of the two books, but because it is a better introduction to the subject.

Field Notes From A Catastrophe details the author's experiences as she traveled, met, and conversed with several leading authorities of the climate change issue. The first chapters explain some of the negative effects of climate change on nature, while the later chapters deal with how climate change has affected man and civilization in the past, how it will likely affect us in the future, and how political leaders are squandering the last few years we have left to make much of difference - all in order to appease their big-time cash contributors.

The author excels in letting experts in the field tell the story for her. For example, in explaining the devastating consequence of modest, but prolonged, local climate change to an ancient middle-eastern civilization the leading paleo-climatologist to study the case says, "The thing they couldn't prepare for was the same thing that we won't prepare for, because in their case they didn't know about it and because in our case the political system can't listen to it. And that is that the climate system has much greater things in store for us than we think."

I highly recommend this book. For more advanced scientific information about climate change many other good books are available (including The Weather Makers), but for an introduction to the subject this one is great. -

This is a really good primer on climate change, the perfect gift for your conservative uncle who thinks climate change is a liberal conspiracy. Although he wouldn’t read it, which is why so many people still ignore this crucial issue: they don’t care about science and reality.

Published in 2006, I was struck over and over again by how little we have done to address climate change since this book came out. It’s depressing is that some things are still the same. James Inhoffe, for example, is featured in this book, quoting Michael Chricton in defense of his climate change denial, calling climate change “the greatest hoax every perpetrated on the American people.” Today, idiots argue from the Senate floor, holding snowballs, that climate change isn’t real.

However, even though the Bush administration was terrible in terms of taking on climate change, at least they acknowledged it was real, where now an entire major political party has colluded to pretend it all isn’t happening.

Kolbert takes a broad view of climate change, tackling it from a variety of perspectives through a field notes approach. I won’t summarize them, but it’s impressive how many perspectives she’s able to incorporate into such a short and readable book. It’s well-written, conscientious and cautionary, a book everyone who cares about our planet should read.

The only negative thing I found in this book is Kolbert’s habit of introducing a new climate scientist or academic and immediately describing their eyes, their noses, etc., comparing them to some other famous person in some way. After the third or fourth instance, it started to get really old and formulaic, but luckily skippable. Other than that, this book is phenomenal. I just wish it were fiction and not reality. -

Just for reference, I read this book after having read The Sixth Extinction first. This only happened because The Sixth Extinction was the Chicago Public Library's book club selection. I am glad I was able to read both books. Both are very insightful into climate change but, in retrospect, I feel it would make better sense to read this book before The Sixth Extinction.

This book is entirely about climate change. The science and jargon is not entirely difficult to follow along. It should be noted that I read a later, revised edition of this book which included 3 new chapters on articles the author wrote years after the initial publication. The new chapters are very much interesting and easy to read. I feel this book would serve as a good segway into reading The Sixth Extinction, which won the Pulitzer Prize. As it turns out, climate is only just one part of what will ultimately place us in the process of a major extinction event. Some of the research and stories the author shares in this book will also be showcased and shown on a broader scale in The Sixth Extinction.

Even as a layman on science, I would recommend this book. -

As Kolbert states in her introduction, this booked is aimed more at the climate change sceptics than those already convinced but it is still a very good read. It is written in clear and concise terms while trying to be as objective and as calm as possible about the evidence there is for anthropogenic climate change, despite the obvious (and understandable) temption to dive into the implications of what we as a species are doing. Kolbert has managed to avoid the usual trap of preaching to the reader about the implications of not taking action as soon as is humanly possible and has focused on what can be proved based on the data available. The only issue I had with this was the inconsistancies between the measurements used, with units alternating between metric and imperial with no translation into the opposite unit so they can be compared easily. Overall a good insightful read that is accessible to everyone, which given the subject matter is rather imperative

-

To cite a well worn phrase, this is a must read to gain an insight and understanding of climate change.....

(The updated and revised edition...) -

This book collects several beautifully-written articles written by the author for the New Yorker on the subject of climate change. Taken together, they form an excellent survey of many of the primary relevant topics. It is outstanding by every metric.

The areas Kolbert covers include: losses of ice and permafrost, a history of the science behind global warming, a look at extinction threats to animal species, climate history and archaeology, modeling, flooding, conservation costs and strategies, the history of climate policy agreements, case studies of municipalities taking on climate change, ocean acidification, and threats to corals and shell-producing animals.

As you can see, she covers a lot of ground.

The book is a collection of individual articles written by a journalist instead of a unified book, and it sometimes shows artifacts of that fact, such as a minor amount of repetition. But in the main, this approach serves the subject well, because of the narrative character of her approach. Over the years, Kolbert has been to many locales first hand, checking out the tar sand mining operations of Alberta, scientific conferences on acidification, glacier sites in Iceland and Alaska, and more. In these stories, she brings us with her on those journeys, bringing the scientists and the science to life with expertly-crafted prose. It's just masterful, the way some of these articles unfold like a detective story, carefully setting you up with the relevant information so that when she delivers the punchline, it immediately lands with full force. I'm very impressed.

The one thing the book could use, and which she acknowledges people have frequently asked her for, is suggestions about what concerned readers can do. She makes the case for the severity of the issue, but doesn't have any advice for where to turn. It can leave you feeling like this is all inevitable, and I sometimes got the impression that that's essentially her conclusion.

But there is a great deal to be done to take on this complex problem, and many possible ways to get involved, and we should do all of them, now. No individual can solve this issue on their own, but of the countless areas where we need to make progress, we can all just pick one - whatever speaks to our aptitudes, interests, and special field of concern, even if the prognosis is bleak. For, to paraphrase Blake, if the fool persists in their folly, they will become wise. -

I'm reading through Lithub's

365 Books to Start Your Climate Change Library, a reading list in four sections (Classics, Science, Fiction & Poetry, and Ideas). This book is #2 of

Part 4: The Ideas and #3 overall.

Really good intro to some of the key scientific ideas in climate change - thawing permafrost, changing migratory patterns, rising sea levels, melting ice shelves - as well as some of the cultural/political aspects that have made up its history - inaction due to "not enough evidence", cartoon villain-y collusion by Exxon-Mobil, et al., failure by US government to make necessary commitments. You know, the normal uplifting global warming stuff.

This book came out in 2006, meaning last year was the halfway point between its publication and the

deadline to prevent the most disastrous effects of climate change that has gotten a lot of coverage. Whether it's useful or not to think about the climate crisis in terms of deadlines, we can't really afford to spend the next 12 years the same as the last 12.

"It may seem impossible to imagine that a technologically advanced society could choose, in essence, to destroy itself, but that is what we are now in the process of doing." -

Reading this just confirmed that Kolbert has been a fantastic author far before her more recent books. I really appreciate the diversity of perspectives she includes. Sometimes it can be difficult for me to remember that there are people who want to solve the same problems as I do but just have very different approaches. And at this point, it's probably worth considering everything given the scale of the problem we're facing with climate change.

I leave two parting thoughts:

1) Dick Cheney is truly one of the most heinous people to get in power and not only managed to kill countless people in the Middle East, but also dragged the US farther into climate denialism

2) I love the following quote and think I will start using this argument next time someone asks me whether my environmental ideas are "practical":

"I think it's the kind of issue where something looked extremely difficult, and not worth it, and then people changed their minds. Take child labor. We decided we would not have child labor and goods would become more expensive. It's a changed preference system. [...] If it's a problem like that, then asking whether it's practical or not is really not going to help very much. Whether it's practical depends on how much we give a damn." -

The Women's National Book Association sent this book to the White House today (March 9) in honor of Women's History Month:

https://www.wnba-centennial.org/book-...

From the Women's National Book Association's press release:

In Field Notes from a Catastrophe, Elizabeth Kolbert documents her travels around the world to sites already affected by man-made climate change, including Alaska, the Arctic, Greenland, and the Netherlands. Kolbert not only witnesses rising sea levels, altered patterns of migration, thawing permafrost, and thinning ice shelves, she also talks to scientists about what we can expect as these changes accelerate. In addition, she shows how Exxon Mobil and other companies have persistently tried to discredit scientists’ warning about the dangers the Earth is facing. In 2012, Kolbert published an updated edition with the new subtitle, Is Time Running Out? This time her message is even more urgent, as she documents further changes and wonders if the catastrophic effects of climate change can still be stopped or at least mitigated. It is a sobering examination of the most important challenge the human race faces. -

Reading a book about climate change and global warming from early 2000s in 2021 is a mixture of interesting reading, sadness and a hint of nostalgia. Kolbert is an amazing writer and her style is very enjoyable.

What makes this book, as well as her more famous Sixth Extinction very interesting, is how unapocalyptic they are - she describes changes in natural phenomena (mostly focuses on glaciers and permafrost) and human adaptations to changing climate, but she doesn’t sound ‘activistic’. Rather, she presents the climate change also form the perspectives of scientific, human studies of it (did you know that the effect of greenhouse gases on climate was known in mid-19th century? I was genuinely surprised.) and probably much like in Sixth Extinction, this perspective and longer view makes a more cold-headed reading.

Generally, this book is not too depressing introduction read and to some extent a ‘periodic’ piece (discussions about Bush administration’s climate policies are funny), that is useful in grounding the debate about current climate crisis in deeper factual and historical basis. -

What I learned first from Elizabeth Kolbert’s Field Notes from a Catasrophe I relearned in the zoom session Jesa attended: how the Pinatubo eruption contributed to the cooling of the planet’s temperature, however short-lived (in ‘geologic’ time). Kolbert: “Volcanic eruptions release huge quantities of sulfur dioxide—Pinatubo produced some twenty million tons of gas—which, once in the stratosphere, condenses into tiny sulfate droplets.” These droplets in turn prevent the absorption of sunlight, instead reflect it “back into space” (103). It’s not a small decision to paint your house either with a dark or light color; or the kind of clothes you’ll be packing on a trip to a province like, say Isabela or Cagayan, known for their roof-raising temperature you wish roofs are literally raised higher for better ventilation. White, brighter colors would reflect sunlight back; darker colors would absorb them, putting more heat onto your body, or your house.

https://nordis.net/2021/06/20/article... -

This book was published in 2006, so is not really up to date... and that makes it even more discouraging. 17 years later, governments still aren't taking seriously this issue and people are still creating insane conspirative theories to debunk the science supporting it *screams*

This is a moderate analysis of the problem, facts, not discourse, laying with clarity the links between this and the big petrol companies and industrial conglomerates, particularly in the USA.

She makes some very details observations of what was going on in the Artic at the time, and sadly but not surprisingly, it's quite obvious that things had gone from bad to worse.

A very interesting reading, easy to read and understand. -

3.5/5 “The Sixth Extinction” by the author is a masterpiece - interestingly written and with the right amount of history, science and anecdotal evidence of climate change. This one written earlier falls short and is a clumsy stitched-up book made from her 3 articles.

BTW, I started this book on the day when US Election Results (2020) started coming in. The first chapter (also the best of the book) was about how a village had to be shifted from the tip of Alaska to mainland at a cost of few hundred million dollars. And guess who was leading by a huge margin in Alaska ? Trump. Laloo-type hold on his votebank. Thankfully it has lasted only 4 years. -

Interesting to read this book from 2005 now, in 2018. Kolbert's book was one of the first to start to bring together the various threads of climate change happening around the globe. It's a well-reported and accessible book. But it's disappointing, when you compare what things were like in 2005 with now - there hasn't been much progress despite much political posturing.

-

I picked this one up based on the author after reading her The Sixth Extinction, it is equally good and the examples are telling even if it’s a bit dated now. She talks with Bush appointees and his policies, and I felt like saying ugh, it’s even worse now...but the patterns and problems hold still, apparently no matter who is in office. So maybe it’s less dated than I would have hoped (only the names change) because we haven’t changed much.