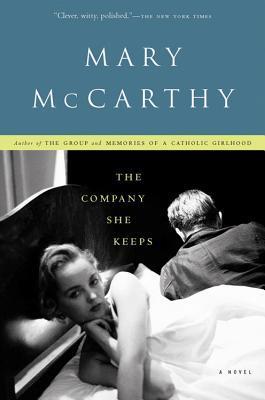

| Title | : | The Company She Keeps |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0156027860 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780156027861 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 304 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1942 |

The Company She Keeps Reviews

-

Act One (How I Met Mary)

What is it you want in a muse?

It's not always about sex or just about sex, because the sex is relatively easy to come by.

Just because you have sex, in a cab, in a room, in your apartment, in your home, in your mansion, doesn't mean that a woman will be your muse.

Did I know that Mary would be my muse? Did I even know I would have sex with her?

Did I know what role she would play in my life?

Did I know just how much she would complicate my life? Did I know how complicated it would get in such a short time?

Part of me wants to say, "No!" But then, to be honest, I have to disagree with myself, again.

She walked into my gallery one day in 1936.

I'd only been in business for two years, but I have to admit I was doing OK.

It helped that I had finished a law degree, courtesy of my parents' ambition for me. I'd even practised for a few years, before I set up the gallery.

What the law meant for me was that I knew people with money, initially lawyers, then accountants, then their clients, executives, business people.

I wasn't happy with my assistant Doris from the start.

I took her on as a sort of favour to a college friend, now an attorney, who'd dated her for a few months and was trying to extricate himself from a problematical relationship.

Attractive as she was, I resisted the temptation to court her initially, because I thought there was still a chance that my friend would reclaim her.

He never did, but gradually our relationship took on the complexion of a chaste marriage and it stayed that way. Effective, efficient, sexless.

We worked well as a team, but we never fired.

Then, one day, Mary walked in the door, clicked her heels as she came to a standstill, and presented me with a resume and a smile.

I sent Doris out to get some coffee and pastries for two.

On the way out, Doris looked me in the eye, I barely paid attention, I should have, I know, now I remember the way she inhaled and held her breath, and she never returned.

Mary was now part of my life, well, this part of my life.

Act Two (Capturing Her Essence)

What can I say about Mary?

What is something about Mary I can tell you in order to capture her essence?

I have to start with her intelligence.

She is the most intelligent woman I've ever met.

No, that's wrong, she's the most intelligent person I've ever met.

Her intelligence operated at a level where gender was irrelevant.

Everything she said, thought, wrote was incisive.

There was never any waffle or wastage.

You only got what was necessary, essential, the essence of her opinion.

She wasn't classically beautiful in that pretty way insisted on by Hollywood.

However, I loved the structure of her face, her jaw, its lines. It was sculpted, the design of some Great Maker.

When I knew her, she still had some freckles sprinkled across the ridge of her nose, like light chocolate hundreds and thousands.

They faded over time, with age and make-up, though I'm told that they resurfaced late in life.

She had a dignity about her, one that spoke of organisation and competence, I imagined her as some agrarian matron or matriarch.

She could run a family, a farm, an enterprise, a dynasty, with equal magnanimity.

I suppose I fell in love with her on that first day in 1936, though what I learned from Mary (or what she taught me) was that it wasn't "her" that I fell in love with.

I think I fell in love with some Grand Design.

Within this thing was Me and a space for someone else, my Other, perhaps my Doppelganger.

The thing is that the second person wasn't defined in terms of another person, they were defined by their relationship with me and what I was seeking.

Whoever it was going to be was going to be within the Grand Design, this picture of my Life, because they fitted the picture.

Without a word, Mary knew that wasn't her role in life.

She wasn't just the left hand side of someone else's picture.

She wanted to be loved for what she was, uniquely.

Perhaps, she was creating her own picture and making the same aesthetic decision about who would be in it, I don't know.

There is also a sense in which, unlike me, she didn't really need someone in her picture.

It was enough that there be a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman.

It embarrasses me to say that during the 12 months she worked with me, for me, I loved her every minute of every day and I confessed and proclaimed my love.

She made me proclaim my love.

No, that's not right, something deep inside me made me confess. Being near her just turned this tendency on, whether or not she or I wanted it on.

I grovelled, I went beyond love, I obsessed about her, I craved her, I made a fool of myself.

I would do anything to prove I was worthy of her love. Instead, my impatient desire made it inevitable that nothing would eventuate between us.

If I had been more patient, would something have eventuated?

I don't think so. We just weren't destined to be in the same picture. She knew that from the beginning.

Still, she valued my attention, before I grew manic.

There were many women who wanted to be in my Grand Design, and ultimately two fitted into it for a time.

Mary liked the fact that others craved what she declined.

The funny thing is that, a few years later, when I had been engaged to Diane for three months and was only six weeks away from our wedding day, Mary and I stumbled across each other at an Art Conference in Boston.

We both spoke, although I hadn't read the Agenda closely enough to see who else was attending. I just wanted to check that the organisers had spelt my name correctly (they often omit the "e").

She complimented my address at dinner, and it so happened that our rooms were on the same floor, so we left together.

We were still mid-conversation, I think we were talking about German Expressionism, when we arrived at her door first.

She invited me in to continue our discussion and have a sherry (she'd brought a bottle of Pedro Ximenez).

I swear that there was no suggestion of anything else and there was no longer any desire on my part.

I had worked damned hard to be able to be in the same room as her and feel neither grief nor lust.

We finished our sherry and I made to leave.

Then she said, "Don't you want to sleep with me?"

It pains me to say that, after everything I'd been through (put myself through) and everything I'd done to repair myself, in that instant, of course I wanted to sleep with her.

I don't know what motivated her, perhaps it was the alcohol, perhaps it was the fact that she had always been attracted to me, she just didn't want a relationship and she definitely didn't want someone craving her like I had done.

Yet, now that there was nothing at stake, she/we could both afford this indulgence.

Was it everything I'd ever expected?

Neither of us went about things as passionately as I had imagined we would every night for those 12 months.

We were both kind, considerate, attentive, and I have to say our simultaneous climax had a kind of designer perfection about it.

I imagined that this is how it would have been if she had let me into her picture rather than she forming part of my Grand Design.

Only I was to come into frame just this once.

Act Three (Farewell My Lovely)

In a way, we had consummated the relationship we had never had.

She had punctuated my lingering obsession with a full stop, a period.

I could stop obsessing, thinking of her as my muse, blaming her every time I had a writer's block.

I could get on with my life.

She might also have left me a little victory, although in reality it was a gift of her own choosing.

I only realised months later that she had been engaged at the time as well, to Edmund Wilson.

Perhaps we both had to rid ourselves of our vulnerability to infidelity.

Although I had been required (chose) to cheat on Diane, Mary actually did me a favour.

I could not have married Diane while Mary remained unfinished business, no matter how much I kidded myself that I had gotten over her.

Against Diane's wishes, I invited Mary to our wedding, though she regretfully and regrettably declined, because of a longstanding commitment in Paris.

We saw each other frequently for many years, not by design, but because we mixed in the same peer group.

She supported my art criticism, she occasionally bought some of my works, even one of my own paintings.

So there is a little bit of me on one of her walls somewhere.

In these short reminiscences, I guess I have endeavoured to capture the essence of Mary.

But the truth is that Mary could never be captured, by me or by anyone else.

Whether it was her female nature or her human nature, she was a mare that wanted to roam free and settle down only as and when she felt the need to.

While she was a competent and caring mother (as she was in every role she took on), she wanted to be able to let her imagination run wild, so that only she could tame it in order to reduce it to words of total insight and crystalline clarity.

We should all be grateful that there are women, men too, whose imagination runs wild, even for a short time, especially if they're able to capture some of it themselves.

They are as rare as stardust falling to earth.

March 30, 2012

Soundtrack ("For A Dancer")

I wrote this review in gratitude for those who dance while they walk this earth.

We are only here for a short time, before we go drifting back into space.

Jackson Browne - "For a Dancer"

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uVG5k_...

Keep a fire for the human race

Let your prayers go drifting into space

You never know what will be coming down

Perhaps a better world is drawing near

And just as easily it could all disappear

Along with whatever meaning you might have found

Don't let the uncertainty turn you around

(the world keeps turning around and around)

Go on and make a joyful sound

Into a dancer you have grown

From a seed somebody else has thrown

Go on ahead and throw some seeds of your own

And somewhere between the time you arrive

And the time you go

May lie a reason you were alive

But you'll never know -

A young woman gets divorced and decides to live life as a Bohemian in New York in the 1930s. If only the book were as good as that synopsis sounds. The novel is split into six vignettes telling the story of our heroine through the men she meets. I thought this would be up my alley but I found it to be quite boring really. I did enjoy the numerous conversations about Trotsky, however. And I liked how it gave us a glimpse into life in New York in the 30s which is never a bad thing. It's a gallant first novel though and I applaud it for that.

-

Mary McCarthy is my 1930s soul sister. She was a hussy of incomparable wit with a somewhat tragic past (orphaned by the Spanish flu pandemic, sent to live with a sadistic aunt). All the reviews of this book mention it as her

succès de scandale because of her habits in the bedroom, but if published today I'd imagine her

Trotskyism would garner more attention. At any rate, it's not her objectionable behavior that makes the stories good, but instead her clever characters. My favorite story was probably "Rogue's Gallery," about her time employed as the stenographer for a con-man gallery owner and the friendship that grew between them. And at the risk of sounding bitter, I loved her cynical sketches of men in relationships, particularly in "The Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt" (cross-country train affair!) and "Portrait of the Intellectual as a Yale Man" (oh snap! this story is such a good burn!). At this point I've already got her best known work, The Group, her "intellectually rigorous" correspondence with

Hannah Arendt, and one of her

biographies queued up at the library. Will let you know how they turn out. -

Trotsky, sex and Freud in the 30s; a time when Americans were allowed to call themselves socialists. Margaret was great and, like Gloria in "BUtterfield 8", not afraid of looking at herself in the mirror. The men were all a bit pathetic and believable

"Sentences were short, and points in the argument clicked like bright billiard balls." -

Since I moved to a big city when I was 18, and had to start dealing with scads of people running into me, bumping into me, forcing their lives into my sphere of awareness, I've decided that a particular kind of friend is necessary--the friend with whom you can be your most wicked, outrageous, mean, scandalous, ill-spirited self.

This friend may not be your closest friend; in fact, if this friend is your closest pal, you might want to rethink how you live your life. You may have one of these kinds of friends every few years--really more acquaintances, really. But every once in a while, it is nice to grab a drink (or several) and let your darkest, meanest impulses run free.

I think Mary McCarthy is the literary equivalent of this friend, and The Company She Keeps is the book version of going out for drinks with her. Sure, there are more Bolsheviks in this book than there'd be these days, but the drunken poor decisions, the romantic ruthlessness, the casual cruelty? It's all in there, along with a short story about psychoanalysis. -

A brilliant first novel, unfolding in six vignettes, establishing a course parallel in certain ways to the life of McCarthy herself. I found the book more caustic than poetic and there I am making a distinction. Walking 13 miles yesterday left me with a tender knee and I’ve spent the day pondering the restless intellect of McCarthy while avoiding any metaphorical associations with the people I love. Undoubtedly this was a shocking novel when published in 1942, it opens with a rationalization of an affair from a wife’s perspective and continues with a cross country seduction and then explores the sentimental sectarian strife amongst myriad leftists in the years before the Second World War. Almost to be expected it ends on the analyst’s couch. The meandering notion of the confidence man persists as the credits roll.

-

Una raccolta di racconti che in realtà è un romanzo, che in realtà è una specie di autobiografia, che in realtà è quasi un saggio sociologico sull'America degli anni '30: arguto (e compiaciuto), spietato (la protagonista non fa sconti a nessuno ma alla fine i colpi più forti li rivolge contro di sé, in particolare nella seduta psicoanalitica finale), spassoso.

Esordio impressionante: l'autrice all'epoca aveva a malapena trent'anni eppure pare scritto da una che la vita la conosceva eccome. -

margaret sargent appartiene a una delle tipologie di donna che trovo più intristenti. quelle che confondono l'intelligenza con la ricevuta di ritorno dell'ascendente esercitato sugli altri. che vogliono apparire engagé a tutti i costi - va bene qualunque causa, basta avere un pubblico per l'endorsement di turno - e finiscono sempre a indossare un filo di sprezzo nei confronti delle debolezze altrui. nello stesso tempo però eccole inciampare in situazioni che tradiscono la loro vanità, l'insicurezza, le piccole meschinità che spuntano come la smagliatura di una calza mentre credono di accavallare le gambe con disinvoltura.

mccarthy non fa nulla per smussare gli aspetti imbarazzanti della protagonista di questi racconti (o romanzo a episodi che sia), che viene stigmatizzata come ogni singola comparsa dall'inizio alla fine. amanti, datori di lavoro, analista, presunti intellettuali, amici anfitrioni. in questi sei capitoli (due molto belli e gli altri così così, ma non siamo certo all'altezza de il gruppo) ce n'è per tutti, a cominciare proprio dal personaggio femminile che li attraversa. il quale al di là dell'indipendenza e della brillante mondanità (margaret ce la descrive come compiaciuta della propria «conversazione educata, colta, progressista») riesce a risultare irritante e abbastanza pietosa fino alla punta delle scarpette. così dedita a recitare il copione della donna disinibita e intelligente, da sembrare tristemente prigioniera del suo ruolo. e infatti si rivela sempre più interessata all'immagine che trasmette di sé, che non a vivere davvero le esperienze nelle quali si getta.

se ha un amante, inorridisce al pensiero che il marito non la rimpianga a sufficienza, ma si stufa della nuova relazione appena viene meno la variabile rischio. se a una cena di intellettuali sostiene la posizione di un antifascista spagnolo, lo fa perché sentirsi attratta dalle cause impopolari è un lato romantico di sé a cui pensa volentieri. e se accetta di chiudersi per un viaggio intero nello scompartimento di un uomo appena conosciuto, la sua attenzione è tutta a scrutare gli occhi di lui. per scoprire euforica che - almeno all'inizio - il suo sguardo riflette una donna «bella, gaia e intelligente, mondana e innocente, seria e frivola, capricciosa e meritevole di fiducia, spiritosa e triste, cattiva e in realtà buona, il tutto mescolato insieme, contemporaneamente». perfino quando si concederà a lui una seconda volta passata la sbornia, pur trovandolo grossolano e volgare, lo farà per sentirsi altruista e gongolare della situazione percepita.

mccarthy non mostra tenerezza verso nessuno degli attori che (aspetti macchiettistici a parte) hanno popolato realmente anche la sua vita. ma a differenza del suo personaggio è la prima a mettersi con divertimento dentro il mazzo che va a scompigliare. tirandosi così fuori dalla meschinità, lei sì, nel momento in cui preferisce l'auto-ironia alla ben più facile auto-assoluzione.

tre stelle e mezzo -

[2020 reread — still awesome.]

This uniquely structured character study takes six different cross-sectional slices of Mary McCarthy’s autofictional doppelgänger, Margaret Sargent, revealing her facets like specimens under a microscope. Each chapter presents a unique view. A few are straightforward third-person renderings in which Meg is the protagonist; another is a first-person tale in which Meg is the narrator but not (directly) the subject; in another, Meg is a secondary character, a catalyst in the story of another person’s life; another uses an unusual second-person perspective, inviting the reader to inhabit the complex of Meg’s mind. The last of the stories features Meg on her analyst’s couch, and is both expansive and implosive, situating Meg’s self-absorbed psychology and relentless need to impress, illuminating the context of her childhood and the patterns of her life.

It’s one of the most brilliant and insightful books I’ve ever read; as McCarthy’s first and perhaps most innovative book, it contains within it the seeds of everything she was as a person and as a writer. It is hilariously wry and bitingly insightful; the first chapter, “Cruel and Barbarous Treatment,” is a scalpel-sharp dissection of the forces that drive a young woman to selfish and destructive behaviors, while a later chapter, “Portrait of the Intellectual as a Yale Man,” dismantles the hypocrisy of the privileged left, poking fun at the internecine squabbles that divided Trotskyite from Stalinist in the New York publishing industry of the 1930s. And there is a charming self-deprecation to all of these skewers, a holding up of a harshly-lit mirror, because so much of Meg is drawn from McCarthy’s own life, and the circles in which Meg moves were then McCarthy’s circles. Like Meg on the analyst’s couch, McCarthy at her writing desk examines herself with what at the time passed for a scientific method: insights, blind spots, self-absorption, self-destruction, and all.

McCarthy’s wonderful novel The Group is similarly arch and self-deprecating, lambasting the naive self-righteous privilege of the liberal elite in the form of eight young Vassar graduates, one of whom again stands in for McCarthy herself (and takes the brunt of the book’s cruelty). As much as I love that book, I am tempted to say that The Company She Keeps is even better, for its innovative structure and the intensity of its focus. What a book; what a writer. -

The Company She Keeps is the life of Margaret Sargeant told in short stories. Margaret, a cosmopolitan intellectual, lived a modern life in the 1930s as a single career woman with many interests, experiences, and lovers. I was struck most by the vibrant intellectual (read Marxist) world portrayed in the novel. McCarthy has a distinctive voice that feels modern even today. This, McCarthy's first novel was controversial at its publication for its frank and open discussion of sex. But within that discussion, the work is also a cautionary tale. Margaret lived a fast life, twice married, and by the last story, she is marginalized as a childless, depressed woman.

-

I'd previously read McCarthy's 'The Group' and 'Memories of a Catholic Girlhood', giving high marks to both. This earlier work, reportedly semi-autobiographical, is rather less engaging.

The author was clearly in the throes of playing extravagantly with her words. Often adept at the turn of phrase, she's also a 'serial killer' with simile.

It seems McCarthy couldn't hold herself back from being over-analytical or parading her intelligence. The writing is showy, less-disciplined, and the author comes off as something like a helicopter mom - not letting the reader ever forget that she is in attendance, and in-charge.

With only one of the six interrelated stories is there a reprieve - and that's because the main character throughout (the McCarthy stand-in, Margaret Sargent) effectively takes a noticeably peripheral position.

In that story - the second one, 'Rogue's Gallery' - Meg is office assistant to a wheeler dealer named Mr. Sheer. Sheer runs an ill-defined art gallery chronically on the verge of being run into the ground. His taste is questionable; his business acumen is appalling. Meg and her winning ways are used to dodge creditors and clients.

Because McCarthy puts Meg in the back seat, she allows herself to be a better writer. The portrait of Sheer is the standout in this collection. He may be pathetic but he's a marvelously drawn character. What ultimately becomes of him is simultaneously unexpected yet makes complete sense.

Elsewhere, Meg deals with various men in ways not particularly compelling. All of that leads, in the final story, to a single, protracted couch session with an analyst. Analysis, in itself, can be invaluable - but, even with the occasional joke thrown in, it's not all that potent as literature. -

McCarthy's first novel consists of six “episodes,” as the book’s back cover copy aptly describes them with the same protagonist. The first and third are first-rate examples of third-person POV tied closely and solely to the protagonist, along with a decision to narrate dialogue more than present it (free indirect dialogue), as I did in my novel

Sandra Ives, Thomas Ives. It’s amazing that so young a writer had the gumption to play with this approach to fiction. In her hands it’s delightful.

But what really makes this first novel special is McCarthy’s ability to get away with a twist that I hate: the use of second-person narration. She does this in the fourth episode by basically writing as if it were third person, except for the use of “you” instead of “her.” The other factor that makes it work is that McCarthy’s narration continues to be delightful.

The fifth episode is a novella in which the third-person narrator stays close to a man rather than the protagonist. And the sixth episode, third-person close to the protagonist, features an ongoing conversation, with the protagonist’s thoughts interrupting it throughout.

The second episode, which is first person (the protagonist), is not delightful. I found its episodes dull, and the voice is also dull. McCarthy was not yet up to all of her experiments, but these are much more than writing class experiments in POV! -

The six short stories in The Company She Keeps are remarkably uneven - although the saving grace of that is that the weakest come first, and the strongest is at the end. Despite a central protagonist with the same name and biography in each tale, the stories don't read as one continuous tale - in fact they're best sampled, I think, as six distinct vignettes with a few curious overlaps, rather than as a narrative that's meant to flow together.

'Cruel and Barbarous Treatment' and 'Rogue's Gallery' - the first two stories in the collection - are the weakest, but witty and clever even as they lack depth. In some ways, the first half of the collection reads like Jane Austen, flung into the 1930s, and granted permission to talk frankly about sex and swear. There's a vicious undercurrent of amusement that runs through those early tales, as if you're invited to stand outside the protagonist's experience and mock her, just a little. There's a great deal to chew over about social convention, prejudice (racial and sexual), and gender roles in the era, but overall the text (as opposed to subtext) is light and inconsequential.

The last story in the book, however - 'Ghostly Father, I Confess' - is politically and culturally sharp, marvelously clever, and deeply revealing about the traps educated women might walk into, not to mention the traps set by society for their parents, their husbands, and their friends. I found its analysis of "analysis" incredibly insightful, and the conundrum of the protagonist as she's given the keys to her own freedom but can't quite figure out if she should trust herself to use them, very moving. I could rave about this short story for hours - suffice to say the whole book is worth reading for this last installment (and the one before is quite brilliant also). -

My edition is actually a mid-50s Dell plucked from a dumpster which fell apart just slightly faster than I could read it, which always adds a certain piquancy to the experience.

McCarthy wrote two dozen works of fiction and non-fiction over 50 years. She was smack in the middle of the New York literary and political intelligentsia of the mid-20th century (Partisan Review, The Nation etc.).

This is her first work, a novel dealing (in the book jacket language of the time) "frankly" with a sexually-liberated, well-educated young woman, making her way in New York left-wing literary circles. The book is in six chapters that may have been published individually as short stories. The rather autobiographical Margaret Sargeant is at the center of them all but her husbands and lovers come and go, and there are no particular segues from one to the next - a few months or years can go by.

The themes that she treats, somewhat satirically, include the American Communists of the 1930s (mainly in order to be contrarian, Sargeant professes to be a devout Trotskyite) and psychoanalysis on the Upper East Side. -

If you like clever conversation, thoroughly laced with the left-wing politics of the late 30s, this is the book for you. It’s a series of interconnected short stories, set at various points in the life of Margaret Sargent. She’s one of the most self-aware people you’ll ever meet. She shares not just her thoughts, but her judgments of her thoughts, and the reasons behind these judgments.

At the same time, McCarthy only occasionally over-writes. The point of view shifts, and often we see her through the eyes of her lovers, or in glancing and circumstantial ways. Everyone in this book is subject to the same detailed, scrupulous understanding, and it’s always interesting. Everything also happens in a very acutely noted social context. In some of the stories, the intellectual climate of the times pays as vivid a part as any other character. -

I wanted to like this more. The book is made up of six loosely connected stories, all about a young woman (I'm guessing based on the author) and her life in New York in the 1930s, working for a left-wing newpaper and dating and marrying various men. The stories are told from several different viewpoints, and it took me a while to work out that "Margaret" features in each of them. The first story, about a woman who has an affair with a younger man and decides to tell her husband, is rather brilliant, but the others were a bit tedious, especially the one that is Margaret's long internal monologue while seeing her therapist. I ploughed on and finished it, but it wasn't much fun.

-

The book was slow going, but that's just because McCarthy packed so much into each sentence and paragraph that I had to pay close attention to every word I read. It was a lot of effort but totally worth it! Her way of dealing with characters is to pull no punches, to show not only their nobilities but also their weaknesses, and not just the weaknesses that we find acceptable, like "Oh, I love too much!" or "I'm so self-sacrificing!" You know, the ones that can be interpreted as virtuous. No, she plunged the depths of the psyches of her characters and showed us their selfishness and self-centered-ness and their complete lack of perspective when it comes to themselves and their position within the world. Sometimes I had to remind myself that McCarthy had conjured these people out of thin air, because they seemed like they could have - and probably were - based on living, breathing people.

Take, for instance, her story about Jim, the reporter for a well-known liberal magazine, who has an affair with Margaret Sanger, the main character of the novel. You could say Jim is a prototype for the modern brogressive. He's an educated white man with liberal sensibilities who considers himself to be the epitome of rational opinion and thought. If he has an opinion about something, it's because it must be right, while others, whose opinions may be more radical than his, are heavily influenced by their emotions and paranoia. But none of this is to say that Jim seemed like a bad guy, just a bit clueless. In fact, he seemed like a very decent, good-hearted man. And therein lies the brilliance of the character.

No one is spared in this book, not even Margaret Sanger, who has her share of moments of cruelty and emotional myopia mingled with courage and intellectual ferocity. She makes for a fascinating character, though - a Communist-sympathizing radical who moves in bohemian and intellectual circles in the 1930s, one who has affairs and who speaks her mind and is politically active. Which reminds me, I really enjoyed reading about that particular social environment. A book about modern suburbia might speak to my personal experience, but there is something so intellectually satisfying about reading about the ways people interacted and lived in different times and places and cultures (and then also seeing how alike people are, no matter where and when they may have lived).

A note of warning - the book goes really deeply into the politics of the times, and so anyone who isn't familiar with politics - leftist or otherwise - of the 1930s might find themselves lost. Just plow through those passages, though - they are incidental to the larger story. -

Mary McCarthy è una scrittrice molto trascurata e molto brava, con una prosa fulminante, un'intelligenza acuminata, uno sguardo autoironico e spietato sul mondo. Riesce a dire in un giro di frase ciò che a metà degli scrittori americani contemporanei richiederebbe minimo quaranta pagine. Ma, ecco, c'è un fastidioso piccolo 'ma' che sentivo presente fin da quel capolavoro che è 'Il gruppo' e non sono riuscita a definire prima di tre, quattro libri. Al netto di un certo cinismo brillante in voga all'epoca (penso per esempio a Dorothy Parker), e di una coraggiosa rivendicazione programmatica di libertà e indipendenza dal maschio, sembra quasi che Mary ci goda a frequentare solo ed esclusivamente quacquaraquà: uomini meschini, insicuri, tronfî, falsi, volgari. Mai uno non dico meglio di lei, ma minimamente al suo livello. E sì che era bellissima e molto corteggiata, poteva scegliere. Ma lei no, pervicacemente circondata da imbelli imbecilli, roba che nemmeno le quattro squinzie di Sex and the City messe insieme. 'Sembra che la Dama Bruna non abbia mai incontrato un gentiluomo nella sua vita' diceva di lei, sarcastico, Norman Mailer. Aveva ragione. Dì la verità, Mary, ti piace vincere facile.

-

My first Mary McCarthy, and I'm already influenced enough by it to want to write something similar set in Bombay. It's really an episodic novel about the life of one writer, Margaret Sargent, as she shuttles between lovers and uncomfortable situations. However, each chapter can also be read as a stand-alone short story, and that's what I loved about it. She also uses a variety of voices and perspectives throughtout the book, which is helpful, because it keeps the reader alert. My only quibble is with her overly long passages of exposition. In the chapters where we hear directly from the protagonist, there's a sense of urgency and immediacy that is missing from the 'Voice of God' narrations

-

some of the stories are MUCH better than others, hence the rating, but wow. what an amazing debut. her writing is incredible. i find it strange that she hated salinger so because his writing provoked basically the same feelings from me. i suppose there are differences in style but salinger and mccarthy are both incredibly observant, insightful and above all things, narcissistic.

-

More a set of satisfying and perceptive character studies than a novel per se. But once beyond the initial preponderance for Capital Letters, McCarthy has a keen eye for the right metaphor and an incisive insider knowledge of interwar intellectual liberalism.

-

lukewarm feelings about the collection over all, but worthwhile for the parts that stung. what parts stung—STUNG. i wish i hadn't accidentally left the copy with my marked quotations in the beach house i was staying in.

-

“Now, for the first time she saw her own extremity, she saw that it was some failure in self-love that obliged her to snatch blindly at the love of others, hoping to love herself through them, borrowing their feelings, as the moon borrowed light. She herself was a dead planet.”

-

Capisco ora da dove abbiano copiato, attingendo a piene mani, tanti scribacchini americani e nostrani.

-

As a big fan of “The Group” I was keen to try another Mary McCarthy novel—but soon realized I should have stopped with that one. In this book McCarthy does everything that writing teachers and critics say how NOT to start a novel: It doesn’t open in the middle of a scene; there is no dialogue; no characterization; no situations; it’s all summary and exposition with thick, chunky paragraphs that go on and on and on. I waded through about 20 pages before giving up.

-

I enjoyed this though the piercing perception and very direct description had me cringing occasionally--- primarily because I recognized the described behavior or thoughts depicted. McCarthy didn't pull a lot of punches as she used her own life as foundation for these six stories, all linked through one character, Margaret Sargent. She also made clear her thoughts on classism, the middle class as well as on the liberal leanings to socialism or communism. Having come of age during the cold war and living in the 2020s I have been surprised at the way in which "liberals" ( I.e. the college educated upper and upper middleclasses) involved themselves in deep discussion and consideration of socialism and communism in McCarthy's books. There is a lot of meat in this book and plenty of excellent writing to dress it.

-

I have mixed feelings in reading the six short stories that introduce us to Margaret Sargent's story. This is my first exposure to Ms. McCarthy's writing and overall I enjoyed her lyrical and honest storytelling. Reading about how we change as we age, from a young idealist to an older realist, and how we justify these changes to fit in with our youngest self's ideals. The frank thoughts about sex, divorce, affairs, aging, personal conflicts took some time to resonate within my psyche.

By far my favorite is the first story, 'Cruel and Barbarous Treatment', in which we are introduced to a married Margaret who is having an affair with a Young Man. Her narcissistic belief in what she's doing was intriguing and as she and her husband separated, the realization that her husband was 'getting a slight edge in popularity over the Young Man', she realized she had to proceed with the divorce and head to Reno. Great storytelling!

My mixed feelings were spurred on by 'Portrait of the Intellectual.' By far my least favorite as it dragged on and on and I lost interest in the story of Margaret and Jim Barnett quickly. The rambling and political discussions and then the affair and then the quilt of the affair and then the guilt of enjoying the money one was making versus his young ideals....I just couldn't get into it. Although it was my lest favorite story, two quotes I fell in love with were found within it:

'Unable to renounce money, he had renounced the enjoyment of it.'

'"A fortune teller told me I was born to fritter away my talents. I wouldn't want to go against my destiny.'"

For the benefit of my own memory, the stories were (with my twitter notes):

Cruel and Barbarous Treatment - adultery, Young Man, and a trip to Reno

Rogue's Gallery - Gallery con man and how Ms. Sargent keeps the creditors away

The Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt - accidental sex with a married man on her way to Portland to announce her engagement

The Genial Host - man no one likes but everyone goes to his parties

Portrait of the Intellectual as a Yale Man - man with ideals, marries, has kids, and justifies his enjoyment of the comfortable life money provides

Ghostly Fahter, I Confess - revisting sad memories of growing up with a sadistic aunt and the people who think Margaret's crazy -

A collection of stories that add up, more or less, to a novel. It says specifically "A Novel" on the cover. I looked. Twice.

McCarthy's writing isn't flowery and her prose isn't beautiful in a demonstrative way. She's more like an understated piece of antique furniture, maybe a five-hundred-year-old desk, that commands respect for all it has survived. You want to know what sustains her. You don't question her wisdom, no matter how neurotic or anxious she tells you she is, because her vision is clear and penetrating. The paradox of her experience is true for many women -- I saw my own in her stories. Her writing is a commentary on gender that is so solid it would require legions to lift her up and shove her out of the way. An immovable feast.

In Portrait of the Intellectual, she writes from the perspective of a man who is in love with her; she is a sometime Trotskyite, and he views her as a martyr in need of defense. As such, he doesn't defend her because he's truly with her, but rather because it bolsters his self-image as a white knight. He anoints himself the hero of her story, even as he diminishes her bravery in standing up for her beliefs.

"...martyrs are usually unappetizing personally; that is why people treat them so badly; for every noble public man, like Trotsky, you must expect a thousand miserable little followers, but there is really more honor in defending them than in defending the great man, who can speak for himself." -

What a book – what an almost perfect book! My friend and I debated whether to call it a novel, or rather a collection of short stories united by the main character, who’s a young woman named Margaret Sanger. Margaret (I love the name) is well-educated, brilliant, beautiful, and from a good family – at least on her father’s side. And yet she’s neither happy nor too sure of herself (despite thinking of herself quite highly – surprisingly these two are not mutually exclusive), or even nice enough to want to have a coffee with her. I think I would run fast in the opposite direction if I were to meet Margaret. But she is fascinating to watch, or rather to listen to. Mary McCarthy is such a good writer, so observant, so clever and quietly ironic, and so pleasant and accessible – she’s one of those highly competent writers who remind me that writing can be witty and intellectual, and at the same time a joy to read.

My favorites were “The Genial Host” and “The Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt” (this one was pretty shocking), and I liked “Rogue’s Gallery” too, albeit with some reservations.

Why not 5 stars? Well, there were some casually classist and racist and xenophobic moments that made me uncomfortable. Not deal-breaking, but spoiling this otherwise perfect book. A pity, really. I am definitely going to read more of this author; but those reminders of the time and place are for me, and always will be, painful to encounter.