| Title | : | The Days of Abandonment |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1933372001 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781933372006 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 188 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 2002 |

The Days of Abandonment Reviews

-

What happens when a person’s domestic life with spouse and children, their entire personal existence, cracks like a bottle of wine and spills all over the floor?

The Days of Abandonment happens.

The atmosphere of this book is far more powerful than the sum of each of its words. The shape of the telling fits the theme perfectly, and the honesty of Olga, the narrator, allows the reader to share in her experience, to look through every line, to gaze downward and feel the vertigo of the depths, the blackness of inferno.

While Olga’s voice is always painfully honest, I am clean I am true I am playing with my cards on the table, what really strikes the reader is how the language of the narration changes as Olga’s state of mind changes. In the beginning, the writing is slow, thoughtful, quiet, with all the necessary commas and periods. I had taught myself to wait patiently until every emotion imploded and could come out in a tone of calm, my voice held back in my throat so that I could not make a spectacle of myself

As Olga begins to slip beneath the skin of her life, as she folds back her own flesh to reveal her raw and vulnerable centre, the language becomes raw, bleeding, piercing, hold the commas, hold the periods this is abandonment

She, we, cannot survive like this, we think. Everyone needs a skin to protect them, and we read on faster, suffering alongside her, willing her to draw her edges together and sew them up with one of her mother’s darning needles so that we can feel comfortable and quiet again.

And Olga does move beyond that initial raw phase, and the language follows suit, reflecting her new state of mind. As she begins to weigh up the cost of the years of marriage, what she has given, what has been taken from her, what she has renounced, what she is left with, her voice has a dangerous calm to it. She speaks of cutting, of excising the past, I wanted to cut myself to pieces, and we read on, one hand covering our eyes even as we strain to take in every word, because in this book, every word counts, every word performs.

Olga’s story is not new but this is an original telling of it. Ferrante is unafraid. She is unafraid of confronting feelings, of calling things by their real names. The term 'abandonment' is interesting. It gives two messages so I looked to see what the title was in the original Italian. It’s called

I giorni dell'abbandono, literally the days of abandonment and I wondered if in Italian the word abbandono means as much as it does in English, not only abandoning of spouse, children, pets but also abandoning of inhibitions, abandoning of hope. The blurbs from the Italian Press given on the Goodreads page for this book mention only the first sense, being abandoned by the spouse but I suspect Ferrante has chosen her title well.

'Abandonment' is not a word that many of us might use easily when speaking of the break-up of a family. We might prefer to talk of a spouse having left the family home; we might prefer to think of the one remaining behind keeping his/her dignity; we might expect that the children would become the priority; we might see the one left behind holding everything together, children, home, work, yes, even finding time to walk the family pet. Ferrante says that this is not the way it really happens, that something always has to give. In her version, that something is Olga’s centre: it doesn’t hold. In her version, pain is not hidden behind a brave face: it shrieks to the heavens. In her version, it is inevitable that there will be an absence of sense, that there will be abandonment of normal living.

Ferrante's book is essentially something you feel more than you actually read and that's why her writing reminds me of Frida Kahlo’s paintings. This one for example:

The absent husband, the large white figure in overalls, still has a firm grip on the wife; her arms are cut off so that she can no longer hold onto anything; her own career, her real self is reduced to a skeleton in the corner.

And this song from Chavela Vargas gives an idea of the intensity of feeling in Ferrante’s writing. The lyrics are simple but eloquent:

I'm tired of crying with no hope

I don't know whether to curse you or pray for you

I'm afraid to look for you and find you

Where my friends assured me you go

There are times when I'd like to die

And release myself from this suffering

But my eyes will die without seeing yours

And at dawn my love will be waiting for you again

As for you, you are partying

Black dove, black dove, where are you?

You shouldn't play with my pride

Since your affection should have been mine and no one else's.

And even though I love you madly, don't come back

I want to be free, live my life with someone I love

God give me strength because I'm dying to go look for him

Here is the

song sung by Vargas. -

Oh dear!

Basically the Neapolitan novels render this book completely obsolete. It’s like a crude test drive for the character of Elena.

Elena is called Olga in this novel and is the woman from hell. A kind of fantasy creation of how we might behave in our most self-indulgent, man-hating and self-pitying incarnation. Essentially she’s an educated thirty eight woman who behaves like an adolescent crackhead. I could imagine Meryl Streep playing her in a film, except the film I saw would have been a comedy and Streep would have been brilliantly funny. And that’s maybe the problem. This novel should have been a comedy – it realises this a couple of times and then it’s very funny. But the tone and prose is so self-consciously pretentious and purple that I found myself laughing at the book rather than with it.

Basically this is the story of a woman who is left by her husband for a much younger woman. It’s a clichéd subject which again begs for some humour. Olga reacts in a clichéd manner – she falls apart - so clichéd that it might be funny if it wasn’t so over-written and so awkwardly and unconvincingly philosophical. If Olga runs a bath you know the bath is going to overflow. If Olga lets her dog off the leash you know something bad is going to happen to the dog. In other words this is a novel of relentless melodrama. Except the high-minded self-indulgent prose rarely recognises the necessity of digging out the comedy in melodrama. For the most part it takes all its melodrama seriously.

Here’s an example of the vaporous philosophical claptrap this novel abounds in - “Existence is this, I thought, a start of joy, a stab of pain, an intense pleasure, veins that pulse under the skin, there is no other truth to tell.” Banality dressed up as gravitas by purple prose.

All in all I got the sense of a writer still trying to find her voice, still learning how to construct sentences even. In a nutshell I don’t think this should ever have been published. It’s disconcerting when you read an early novel by an author you’ve come to love and find it thoroughly mediocre, or worse. It happened to me with Anthony Doerr as well. You end up thinking maybe your original enthusiasm was misplaced. I’m not going to read any more of the early Ferrante novels. -

"the gripping story of a woman's descent into emptiness"...i don't remember selling my life rights to elena ferrante

-

Almodovar's "Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown" + Margaret Atwood's terrific uberfeminist two first published novels + Charlotte Perkins Gilman's short story avatar heroine from The Yellow Wallpaper = THIS, a novel with absolutely perfect symbolism that describes the descent of this woman goin' bonkers, with the overflow of emotions which invades her after being left for the "other woman." Incendiary & insightful, Elena Ferrante is one authentic discovery!

-

This is the sixth novel I have read by

Elena Ferrante, and let me tell you her characters are not introspective, contemplative people. They are angry people pissed off in a variety of complex ways about why their lives have turned to shit. In The Days of Abandonment a husband leaves his wife and two children. The wife, our narrator, is incapable of finding a way to live singly. Slowly she falls apart. Not halfway through yet and I’m beginning to wonder if she may not end up institutionalized. There are these mental lapses, emotional tirades. The pitch is growing more and more off-kilter. Will she throw herself under a train, like

Anna Karenina? Will she become a holy terror like Lila in

The Neapolitan Novels?

She has given her husband, Mario, everything. She pretty much forced marched him—a timid man—through his own college education. How many times have we heard a story like this? Ad infinitium. Ferrante as always takes the commonplace human drama and makes it extraordinary. And in the middle of the blindsiding abandonment—her husband of 15 years leaves her after no more than 15 minute of self-justification—the terrible children blame everything on her. She speaks of “the stink of motherhood.” She’s this close to hitting them with the backside of her hand. For all the knives are out in Ferrante, nothing is held back, though it may take a little while to unsheath the blades.

You’re going to love it when she blows up at the utility and phone companies. Now that’s vicarious joy. And when she finds Mario and his whore on the street?—magic. Then she throws herself on a male neighbor who comes up impotent, vainly fellates him into turgidity. The story can be both heartbreaking and hilarious at once. My God, what an artistic vision! What a lot of laughing out loud I’m doing while reading. This is a novel thick with the bodily fluids of sex, childbirth and blood. The stink of motherhood. The novels of Ferrante do one thing for me: they make me delighted to be without offspring, and make my heart go out to those who undertake that impossible job.

Slowly she loses the ability to concentrate. She seems to be casting herself free of responsibility. She forgets to pay the bills, forgets to get the telephone fixed, forgets her son’s sudden illness. Is he dying? Otto the dog is ill, possibly poisoned by the very neighbor she has just tried to reconfirm her femininity with last night. This is pathological. The mood turns Felliniesque when her daughter reappears—after getting into her dresses and makeup—in a form she likens to twin dwarves she saw perform as a child. I'll keep quiet on what happens next. This is a well-plotted book that rises to the level of literary fiction. Please read it. -

I first heard about Elena Ferrante about a year ago when everyone seemed to read her Neapolitan saga. So I joined the club too and read My brilliant friend, the first installment of the series. I pretty liked that one though to be honest sometimes I was lost in the plethora of names and constantly confused who was who and with whom. I didn’t find the language especially captivating but it was nicely written and I hadn’t any problem with reading it. But if I had to indicate any reservation it would probably be the voices of two main protagonists. Sometimes I just couldn’t hear them in the spate of events and other protagonists.

Otherwise The days of abandonment. Here nothing distracts us, nothing diverts our attention from our heroine. Olga, well-groomed, happy wife and mother of two, all of a sudden finds herself abandoned and excluded from previous life. Nothing new, one could say. Not necessarily because as classic says all happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. When I mention this quote it is also due to some similarity to Anna Karenina that Olga deeply feels.

Olga is a nice person, kind and gentle but abandoned by husband, gradually and inexorably changes and the novel is a meticulous, sometimes so detailed that it just hurts, description of these changes, her shifting moods, her omissions, her lack of security, her losing integrity. Her days of abandonment. Firstly is an act of denying, that delusive it’s nothing, everything will be fine phase. And of course it is not. So she slowly enters the more and more dark and bleak areas. Her changing moods, verbal exhibitionism, almost diarrhea of vulgar thoughts, obscene language and imagined scenes of perverse sex are painful and very reliable though at times unbearable. But from the other hand her anguish, her lips that miss to be kissed, her body that needs to be caressed makes you empathize with her and you can’t wait when Olga finally escapes from the abyss of own obsessive thoughts and deeds, that she wouldn’t share her lot with poverella , poor abandoned woman, almost mythical creature from Olga's childhood, who finally drowned herself to death.

We all know such women like Olga, who gave themselves to their husbands or lovers so entirely, who gave own body, heart and mind not leaving to oneself any single thing to be named own. To escape that state, pick up the pieces, relearn life, rename things, define anew what really counts is as painful as previous falling into darkness and disintegration. -

Ferrante is a master at capturing human emotion. Not only that, her sentences are so delightful and can turn from horrifying to elating in a matter of seconds. I'm happy to say this one did not disappoint.

-

عزيزتى إلينا فيرانتي :

أيا كان اسمك الحقيقي وايا كان سنك ومنصبك وايا كان شكل حياتك .

اسمحيلى أشكرك وأرفع لك القبعة إعجابا بأسلوبك وكتاباتك واختيارك لعرض شخصياتك .لديك القدرة أن تجعلينى أغضب وأشعر بالاستفزاز أحيانا من تصرفات شخصياتك وفى ذات الوقت تجعلينى اتعمق بقوة بداخلهم وأتعاطف معهم و أندمج معهم .

هذه هى الرواية الثانية لى بعد الرباعية أى اللقاء السادس مع إلينا فيرانتى، ولم تخذلينى فى اى لقاء . تنجحين فى جذبي و اجباري على الإندماج مع شخصياتك .

ماريو الذي فاجأ زوجته أولغا برغبته فى أن يتركها " كان يريد مهما كلف الثمن ، ان اراه كما يصف نفسه : رجل لا طائل منه ، عاجز عن الشعور بأحاسيس حقيقية ، ومن دون المستوى حتي فى عمله "

" مثلما كنت أظهر له ، على نحو محسوب ، جميع فضائلي كامرأة مغرمة ، ومستعدة بالتالى لدعمه في هذه الازمة الغامضة ، كان هو أيضا وعلى نحو محسوب، يسعى لإثارة قرفي ليدفعني للقول : ارحل ، إنك تقرفني ، لم أعد أحتملك .

لتتفاجأ بعد ذلك انه يخبرها بانه على علاقة بامرأة اخرى فوجدت نفسها امام مسوؤلية أبنائها والكلب والبيت .و تحاسب نفسها وتستعيد السنوات الماضية فى محاولة منها لتصل لأسباب ماحدث والوصول لحل للإصلاح . لكن هل هناك شيئا يمكن إصلاحه من الأساس ؟

" انا وحدي ساتحمل المسؤوليات التى كانت سابقا من نصيب الاثنين .

كان على ان أتفاعل، ان أنظم نفسي .

لا تستسلمي ، كنت اكرر لنفسي ، لا تهوي الى الأمام .

كيف ستتصرف أولغا مع ما يحدث معها؟ كيف ستكون حياتها وحياة اولادها وعلاقتها بهم بعد هجر ماريو لها ؟ كيف ستتعامل مع الامر ؟ وماهو تأثيره عليها ؟ وعلى ابنائهم جاني وايلاريا ؟

" لماذا رمى بهذه الخفة خمسة عشر عاما من المشاعر ، والانفعالات ، والحب ؟ الزمن ،. أخذ زمن حياتي كله ليتخلص منه بخفة نزوة . يا للقرار الظالم ، الأحادي الجانب ! نفخ الماضي كما ينفخ حشرة استقرت على يده "

فى هذه الرواية شعرت أنى أولغا الزوجة التى تفاجأت ان زوجها سيتركها وتفاجأت بعلاقته بامرأة أخرى . شعرت بتطور رد فعلها تجاه ما حدث . سمعت أفكارها فى رأسى منذ بدايتها ، شعرت وكأني أولغا ،شعرت بتحطم قلبي مع قلبها ، رددت أفكارها ، شعرت بإرهاقها ، تهت معها ، رغبت فى إحتضانها ومساعدتها . ذكرتنى بالمرأة المحطمة لسيمون دى بوفوار .

" كنت زوجة بالية ، جسدا وضع جانبا ، مرضي ليس سوى حياة أنثوية لم تعد قابلة للاستعمال "

" إلى ماذا آلت المرأة التى كنت أتخيل أنني سأكونها في مراهقتي ؟ "

أسلوب السرد ممتع وسلس كعادة إلينا. وبرغم ان فكرة الرواية نفسها وقصتها قد تكون عادية الا ان أسلوب السرد وعرضها لردود أفعال أولغا كان رائع أعجبنى .

شعرت بواقعيته فعند حدوث الانفصال والخيانة والهجر غالبا ما تقع الزوجة في دوامة من الانكار في البداية وانتظار عودته ثم الغضب على الزوج لتركه لها وهدم البيت وتأنيب الذات ومحاسبتها ورؤية عيوبها مضخمة والشعور بالألم والوجع وقد يلي ذلك التماسك واعادة ترتيب الحياة أو الغرق في دوامة الغضب والانكسار واهانة الآخر . ومن جهة أخري يتأثر الابناء بما يحدث وتؤثر عليهم تصرفات الأم ومشاعرها .

شكرا ايلينا وإلى لقاء آخر 💖💖

١٧ / ٣ / ٢٠٢١ -

Look at me, I said to the glass in a whisper, a breath. The mirror was summing up my situation- The worse side, the better side, geometry of the hidden.

The stage is set with everything at its right place. The lunch is prepared, served and without further ado, an unexpected and grievous announcement is made from across the table with a nonchalance rightly belonging to some stranger rather than that one dear person who shared with you yet another embarrassingly funny tale of his teenage self as a prelude to the unexceptional lovemaking just a couple of nights ago. The wonted calm abruptly gets replaced by an uninvited chaos and the neat arrangement of a happy home appears to be the mocking backdrop of a black comedy where things are supposed to take several turns for better or for worse...

Days of Abandonment are here along with an indefinite darkness.

Elena Ferrante by means of a gripping narration develops a combative atmosphere where hope, loneliness and anguish are engaged in an aggressive rivalry to claim their influence in the life of Olga. Olga- the dreamy adolescent, a thoughtful woman, mother of two kids, and a writer driven by need instead of love who now allocates a mere ten ordinary sentences to encapsulate her whole life which has been brutally impeded by the glaring title of ‘abandoned wife’. Abandoned not only by a husband but all those illusions that shaped her perceptions and gave way to a sedate persona that at once crumbled when came face to face with an undeserved misery.

The meanings, the meaning of her life—I suddenly understood—were only a dazzlement of late adolescence, my illusion of stability.

My thoughts while reading this book were diverse and conflicted. After each new chapter, I added one positive point, struck another negative remark and held the ambiguous ones to tease the cynic in me. The writing is suffused with astute observations and a relentless energy that remains faithful to Olga’s erratic state of mind but it demands understanding in a playful manner. Here’s a woman who discards her calculated sophistication and succumbs to a madcap behavior which at times displayed an almost caricatural representation of sentimentality- A grief so gaudy began to repel me. Though soon it becomes clear that what is actually on display is an ingenious show-not-tell example of articulating bewildered senses of an individual who feels utterly defenseless against the extremity of her desperation and simultaneously trying hard to analyse her situation by gathering subtle hints scattered all over her days of unexamined life.If I were to start from there, from those secret emotions, perhaps I would understand better why he had gone and why I, who had always set against the occasional emotional confusion the stable order of our affections, now felt so violently the bitterness of loss, an intolerable grief, the anxiety of falling out of the web of certainties and having to relearn life without the security of knowing how to do it.

Perhaps this is a book Ferrante never aspired to write and this is definitely a story Olga never wanted to live but these stories are like rippled reflections in the ocean of harsher truths that real lives are and one becomes their protagonist owing to that unpredictable stroke of destiny when our dreams never come true but our nightmares sometimes do. -

Not nearly as good as Elena Ferrante's Naples Quartet.

Engaging writing about a husband who leaves his wife and children, but I felt 'neutral'. I read this just before reading "Ties" by Domenico Starnone. A similar type story.

By the end of 'both' novels -- I wanted to fly kites with the kids and get them ice cream cones. The adults can go play in their own sandboxes.

I'm glad I read this short book and "Ties"..... but it made me miss 'the Quartet series.....especially book Two and Three.

Well written........ but Bleak & Pathetic! -

"Nothing you read about Elena Ferrante's work prepares you for the ferocity of it."

—Amy Rowland, The New York Times

The book is acerbic, biting, warm, horrifying, searing, endearing, astounding, changing like the weather. The days, weeks and months following an Italian man’s announcement that he is leaving his wife and two children. Ferrante jolts the reader little more than a hundred words in, by having Olga, her first person narrator, conclude her description of her abandonment: “Then he assumed the blame for everything that was happening and closed the door carefully behind him, leaving me turned to stone beside the sink."

Olga, who is/was a sometime writer, grapples with a woman’s dilemma – why? Am I no longer attractive? Has he become bored with me? Is he having an affair? But mostly she confronts her own past as a young girl, when a neighbor (the poverella that poor woman as she came to be called) was similarly abandoned, fell to pieces, was pitied (and mocked) by other women, eventually committing suicide. Olga’s own mother warns her that the poverella, having endured this ultimate humiliation, is “as dry now as a salted anchovy”, and implies that this is what is inevitable (or maybe not) when a woman loses hold of a man. All these bits of her past swirl around, within, through Olga’s memory, Olga’s mind, her consciousness, her emotions.

This makes the book sound almost like a story for women only, addressing concerns that not even all women would have interest in, a pot-boiler, chick lit. Far from it.

Ferrante’s writing astounds, brings chills to the spine and tears to the eyes, but not because it’s heart-grabbing. No. It’s mind-grabbing. This writing soars. It is such exalted literature that one becomes first surprised, then amazed, then dumbfounded. How has such a writer, an anonymous Italian woman, appeared in these times - one who can be compared to the greatest writers of the last hundred years? (And has been, by several critics.)

It plays with time. It probes the psyche. It dissects memory, tells an ever-accelerating story of a woman’s psychological and physical breakdown.

It descends into the dark night of the human soul. This is The Lord of the Flies, The Pit and the Pendulum, and Roman Polanski’s Repulsion rolled into a sordid, swirling mass, and implanted into the reader’s brain. One is silently screaming with fear and pity, trembling in anticipation of the outcome.

And then somehow, amazingly, believably, Ferrante brings a calm back to Olga, as she finds herself emerging out the other side of her nightmare, perhaps wiser, perhaps more accepting, surely older, more in tune with life as it actually is. Near the end, Olga has a final meeting with her former husband.I looked at him attentively. It was really true, there was no longer anything about him that could interest me. He wasn't even a fragment of the past, he was only a stain, like the print of a hand left years ago on a wall.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Previous review:

To the Lighthouse V. Woolf

Next review:

Summer of '49 baseball

Older review:

The English Patient

Previous library review:

The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony Calasso

Next library review:

My Brilliant Friend Ferrante

-

I hesitate between giving this book 3 or 4 stars. On one hand, it is a visceral, brutal read - the story of Olga's near disintegration in the aftermath of her being abandoned by her husband Marco. On the day that she discovers the identity of the lover for whom Marco has left - and this takes up probably half of the book - all hell breaks loose: her son vomits in his sleep and has a huge fever and her dog (well Mario's dog) gets sick and dies, probably poisoned. In the midst of all this calamity, Olga struggles to hold herself together, but pretty much fails much to the chagrin and disappointment of her daughter. It is incredibly realistic and painful to feel Olga's alienation: from a world where "everything was reduced to an aseptic voice" (p. 68) She tries desperately to put on a brave face: "To those who hurt me. I am giving back in kind. I am the queen of spades. I am the wasp that stings. I am the dark serpent. I am the invulnerable animal who passes through fire and is not burned." (p. 76). Things fall apart and she becomes "A broken clock that, because its metal heart continued to beat, was now breaking the time of everything else." (p. 107) She does manage to survive with her kids and eventually has a final conversation with Mario about their separation in which she confronts him: "Now I know what an absence of sense is and what happens if you manage to get back to the surface of it. You, you don't know. At most, you glanced down, you got frightened, and you plugged up the hole" (p. 185).

As in all of the Ferrante fiction I have read so far, nothing is held back here - the facts and situations come fast and furious with the force of a slap or breaking glass. She has certainly found the vein leading to raw feminine pain which she articulates with such skill and daring. While not as good as the Napolitain novels, Days of Abandonment is nonetheless a powerful read. -

"I wanted to write stories about women with resources, women of invincible words, not a manual for the abandoned wife with her lost love at the top of her thoughts. I was young, I had pretensions. I didn't like the impenetrable page, like a lowered blind. I liked light, air between the slats…I loved the writers who made you look through every line, to gaze downward and feel the vertigo of the depths, the blackness of inferno."

Was this Ferrante speaking through her main character, Olga? The moment we think we know everything, we know nothing at all. So quick we are to judge, so quick to think we have a handle on this thing called life; until life shows us just how cyclical it can be. Who said that a book on women had to work so hard against sensitivity? Why bind the female writer or protagonist and expect her to only tell stories of what the dominant society expects of her; meanwhile, the real issues remain covered. This is what Olga, the protagonist who is also a writer, discovers when she finds herself being the female character she thought she would never write about.

The minute I turned the first page of this book, I knew I was reading a book whose mood would handcuff me, demanding my attention. I knew I would "look through every line" and yes, I did feel "the blackness of inferno." The melancholic tone and pseudo-psychotic voice is what turns these pages, as you live in the head of a woman who has lost herself. She is a mother of two kids and her husband has left her for a younger woman, so this seems like an overstated story, but Olga is not the character you would expect. She manages to be all these things: timid, ferocious, naive, angry, untrusting, sarcastic, and depressed. Better yet, she uses language that will shock you and this is all good because her pain has made her uninhibited and you can tell that it feels good to her and frankly, it adds to the mood of the piece and feels good to be read because at that moment you see her come into herself. She realizes that she really is sinking and she's become one of those women she didn't imagine herself being , "time seemed to be boiling over, flowing in sticky waves out of a pot onto the flames."

Downward goes the spiral.

Hold the commas, hold the periods. It's not easy to go from the happy serenity of a romantic stroll to the chaos, to the incoherence of the world.

This book is not just about another woman who gets dumped. It is about the perplexities of a woman who finds herself suddenly abandoned and alone and she realizes that somehow, she has slowly slipped away from herself, evaporated, and she has no idea how to get back to her core. The more frantic and dangerous Olga became, I feared for her children, I almost cried for the poor dog, and I was frustrated at some parts of the last scenes when I wanted to reach through my book and shake her awake. Isn't this what we do in real life when we see a friend or loved one go through a similar ordeal? This book is about the moment life changes and we don't know what to do with the change, or rather, we don't know how our minds will cope with such change. Will we become Olga?

I had only to quiet the view inside, the thoughts, They got mixed up, they crowded in on one another, shreds of words and images, buzzing frantically, like a swarm of wasps, they gave to my gestures a brute capacity to do harm.

-

I hated this book for 85% of it, then the last 15% weren't all bad, and I kind of lost all that built-up rage... Anyway, I won't let that soften the blow, because this was torture to listen to. I'm not sure how much of my repulsion stems from the book itself, and how much can be blamed on the gratingly bitchy narrator. There's some cleverness in how Olga turns into what she once thought she never would become, but that does in no way redeem the book.

I simply couldn't stand Olga. She's definitely among the worst main characters EVER CREATED. Her confusion, her mental outbursts, her appallingly poor parenting skills (not to mention her ineptitude as a pet owner), her baffling helplessness... And all that nagging about the door and the lock? Aargrgh. Cheap imagery, anyone? All the images used felt forced and awkward and are probably why Ferrante is considered such a great novelist.

For once, I wish the author would have stayed away from vulgarity (both language and scene wise). Because the "crude" language Olga took up while being so "distraught" by Mario leaving felt 500% false and weird and awkward. And that scene with the neighbor... Still makes me shiver with discomfort.

The worst thing about this book is that the premise doesn't really work. We never get to understand why Olga reacts like she does, because Mario remains a paper figure. Perhaps if we'd known some of their marital bliss first, there'd be a shred of sympathy for Olga. But no, we get NOTHING of that sort. And Olga just seems like a parody of an abandoned woman.

Another thing I couldn't quite stomach was the Italianess of it all. The shouting, the "emotion" and "passion" and all that. It just felt fake and improbable and weird, but perhaps Italians think that stuff is normal.

Bleh. Again: HATED IT. -

When you don't know how to keep a man you lose everything.

It is easy to say that the build-up to Olga’s sense of abandonment and her descent into the abyss of her psychological breakdown couldn’t quite hold together after her abrupt transformation back into normality underscored by a sense of contained pain; I don’t know how to put it adequately (I'm feeling as inadequate as people say they do when they review Stoner) but there is something entirely missing from the bigger picture that could, say, put in the right place the accumulated sense of her predicament as we read through the awkward and baffling situation-drama of her self-entrapment in the apartment with her two young children, out of her senses, unable to get out, her mind and body at war with each other.

Staccato, fragmented, three-word sentences mirror the disordered urgency of Olga’s own state of mind, her desperate and repeated attempts to pull herself together, but her eventual coming to terms with her situation happens disconnectedly and unsubtly, as if waking from a nightmare, without giving the reader a chance to adjust to the transition. We often talk about books that could have been trimmed down in order to remove tangential trips, but in this case the reader would have benefited if the author had used a few dozen more pages to inject it with a sense of logical progress.

Our protagonist is fully conscious of the “type” of woman she's on the brink of becoming, magnified by the example of the poverella of her Neapolitan childhood, a poor woman who after long suffering had committed suicide when her husband walked out on her, and despite her resolve to not be like women destroyed in a famous book of your [her] adolescence, she becomes exactly like one, to her utter incomprehension. Every thought, every attempt, every encounter with the new reality pushes her further into becoming the stereotype of the abandoned wife. But make no mistake, the story is anything but a stereotype. It is as though the author has made her protagonist accept the role of the abandoned wife only to mock that role and its ludicrous dimensionless nothingness, but without denying the essential devastation that that position, once you’re put on the spot, brings with it.

To say that Olga’s abandonment and her rapid mental decline lacks context is not criticism (after all, characters and their actions create their own contexts as they roll out) but Mario, her husband, is nothing more than a cardboard whom she fell in love with, married, and had kids with, and who one day abandoned her. We don’t know more about him (a big flaw limiting my readerly sympathy for Olga). We also don’t know anything about Carla, Mario’s young lover. But that’s okay: I didn’t expect the first-person voice of the abandoned wife to be able to flesh her rival up more than calling her a “whore” with “a tight ass” and a “young cunt.” She had opened her thighs, bathed his prick, and imagined that thus she had baptized him, I baptize you with the holy water of the cunt, I immerse your cock in the moist flesh and I rename it, I call it mine and born to a new life. The bitch. So she thought she had full rights to take my place, to play my part, the fucking whore. And that's all we get to know about Carla.

The Days of Abandonment offers excellent talking points, as can be gleaned from reading the community reviews, but the literary makeup of Olga's painful story didn't quite enthuse me, and I still exactly don't know why.

2.5/5

August '16 -

First person novels featuring women going slightly or more than slightly bonkers are not hard to come by, in fact they may be a whole sub-genre. These are some I have read in the last couple of years

Love Me Back by Merritt Tierce in which a waitress has way too much sex and drugs (but hardly any rock and roll)

Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh in which Eileen (who else) is driven to the point of distraction by her alky father and does something really crazy

Dietland by Sarai Walker in which the self loathing of an obese young woman gradually transmutes into some kind of political terrorism

A Day Off by Storm Jameson in which a middle aged woman spends her day off from the sprocket factory hating on anything and everything

The Piano Teacher by Elfriede Jelinek in which a daughter has been driven quite masochistically loopy by her horrible controlling mother

Dept of Speculation by Jenny Offill in which an abandoned wife gradually cracks up

The Days of Abandonment is similar to this last one, except the abandonment by the husband comes from a clear blue sky like a sudden clap of thunder.

One April afternoon, right after lunch, my husband announced that he wanted to leave me.

That’s the first sentence. After that we’re on a fast helter-skelter into mania. I am glad to report that the utter banality of this novel’s storyline – could it be more dull and overused? – is totally justified by the brilliance of Elena Ferrante’s close-up hyperreal portrait of a disintegrating mind. It’s somewhat like Roman Polanski’s terrifying movie Repulsion if Catherine Deneuve had two kids and a dog to look after.

On page 88 Olga, the narrator, says

When I opened my eyes again, five hours later on Saturday August 4th, I had trouble getting my bearings. The hardest day of the ordeal of my abandonment was about to begin, but I didn’t know it yet.

She takes the next 63 pages to describe in excruciating detail the events of the day. Her language wobbles and spins as her mind does and she comes out with stuff like :

The universe of good reasons that I had been given after adolescence was narrowing. No matter how much I had tried to be slow, to have thoughtful gestures, that world over the years had nevertheless moved in too great a whirl, and its globelike figure was reduced to a thin round tablet, so thin that, as fragments splintered off, it appeared to be pierced in the middle , soon it would become like a wedding ring, finally it would dissolve.

At a later point she is inveigled to spend an evening with friends who then crassly attempt to set her up with some random guy. This does not go down well with our Olga:

Evenings like thus. Appearing at the house of strangers, marked as a woman waiting to remake her life. At the mercy of other women who, unhappily married, struggle to propose me to men they consider fascinating. Having to accept the game, not to be able to confess that those men arouse only uneasiness in me, for their explicit goal, known to all present, is to seek contact with my cold body, to warm themselves by warming me, and then to crush me with their role of born seducers, men alone like me, like me frightened by strangers, worn out by failures and by empty years, separated, divorced, widowers, abandoned, betrayed.

Okayyyyyyy…….!

I was going to rate this 3.5 but I seem to have talked myself into 4 stars during the writing of this review. In its demon fury certainly this novel tramps all over the last ten or so that I’ve read. So if you want to be harrowed by desperate misery for a couple of days, you may like this. -

This is as close to perfection a novel told in the first person can achieve. A knock against "women's literature"is that it never aims for, or achieves, a large-scale canvas. Ambitious men prefer architecture over sensitivity, evidence shows. Nothing like reading another 700 page book from Mitchell or Murakami. Ordinarily the lack of curiosity about those outside one's class explains why: the preference for one's circle of intimates where uncertainties and dangers are kept away. In less than 200 pages Ferrante turns the convention upside down, the large-scale over the domestic. Complex plotting in the dissolution of a marriage, it's astonishing that she can achieve a sense of grandeur in a subject so common it's almost not even worth noting.

At last I understand what "vertigo" is - a momentary loss of sanity, you can never really know what freedom is until you've touched upon this loss. The dying dog, the paper-cutter, the smashing of the window. At each step of the way in this environment choices are presented; one is chosen; it leads to disastrous consequences. We think that if that was us we would probably have chosen the other option. But there are no better options - that's the nature of vertigo, that you're trapped in terra incognita. It also dictates Ferrante's outstanding depiction of time passing: the voice is caught in a space between telling a story and explaining herself to herself when she realizes the explanations to herself, up to this point, have been wrong.

Overall it's the complete honesty that's conveyed from a person who is given the opportunity of not having to worry about how she comes across anymore. It's temporary and it opens up this one woman's consciousness beautifully, as it stands for something much larger than herself. A miracle of storytelling, not once did I find the narrator Olga an embarrassment, even though she's trapped in a humiliating situation. If she seems angry she's lashing out at society, not anyone in particular (except for that time when the husband takes a drubbing) so you don't feel the usual finger pointing at you when reading highly upset feminism. It's amazing that for such a political book, politics, on the surface, are absent. The narrator doesn't - and perhaps never has - belonged to anyone, and yet she needs the affections stability brings. Why? That's a large part of the excitement of this novel. How do I look? she asks. She shows us her small breasts (and in her next novel Ferrante has her narrator lifting up her dress at a clothing store to reveal her panties - this kind of exhibitionism in someone this intelligent is not the usual order of things).

An example of the brilliance in storytelling is when Olga brings her children to the office and they can feel the sexual tension between her and a colleague. The usual novelist, with an irritating fallback mode of responsibility, would let us know exactly what that's about - Ferrante touches upon the depth of her character by simply noting it's there.

success depends on the capacity to manipulate the obvious with calculated precision. I didn't know how to adapt, I didn't know how to yield completely to Mario's gaze

The psychological perceptiveness feels so accurate to its aims from start to finish it becomes poetic.

The whole thing depressed me. This is what awaits me, I thought. Evenings like this. Appearing at the house of strangers, marked as a woman waiting to remake her life. At the mercy of other women who, unhappily married, struggle to propose to me men they consider fascinating. Having to accept the game, not to be able to confess that those men arouse only uneasiness in me, for their explicit goal, known to all present, is to feel contact with my cold body, to warm themselves by warming me, and then to crush me with their role of born seducers, men alone like me, like me frightened by strangers, worn out by failures and by empty years, separated, divorced, widowers, abandoned, betrayed.

Ordinarily you don't come across women like this because they don't notice you either.

This one novel single-handedly redeemed my faith in contemporary literature, which I was just about ready to give up. Houellebecq had been funny for a while but now compared to Ferrante he seems a little silly. -

Εντάξει απλά δεν γουστάρω με τίποτα τη Φερράντε. Συμβαίνει και στις καλύτερες οικογένειες. Θα μου πείτε και τότε γιατί τη διαβάζεις κοπέλα μου. Έλα ντε. Θα έλεγα από καθαρή περιέργεια και ανάγκη να καταλάβω και όχι τόσο να αποδεχτώ γιατί στο καλό αυτή η συγγραφέας φάντασμα έγινε εκδοτικό φαινόμενο και τ�� βιβλία της έχουν κατακτήσει όλο τον κόσμο οκ εκτός από μένα. Αν η εμπειρία μου με την τετραλογία της Νάπολης (διάβασα τα 3 από τα 4) ήταν απογοητευτική και μάλλον βαρετή εμπειρία τότε οι μέρες εγκατάλειψης θα έλεγα ότι ήταν απλά αποκαρδιωτική. Υποψιάζομαι ότι θα άγγιξε αρκετό γυναικείο πληθυσμό λόγω της διείσδυσης ας πούμε που προσπαθεί να γίνει στην γυναικεία ψυχολογία και πράγματι και εγώ βρήκα μέσα κανά δυο ατάκες που θα μπορούσα να εχω πει ή σκεφτεί ως γυναίκα αλλά ειλικρινά κρίνω τον ευατό μου αρκετά μίζερο από μόνο του για να κάθομαι να διαβάζω και μίζερα βιβλία. Δεν εχω ξαναδεί πρόσφατα τουλάχιστον πιο ηρωίδα με τέτοια μίρλα και οκ θα το πω ξεκάθαρα και αμαρτία ουκ έχω κλαψομούνα. Θεέ πώς να μη σε παρατήσει χρυσή μου γυναίκα ο άντρας. Σου φταίει όλο μα όλο το σύμπαν αντί να σκεφτείς ότι από μόνη σου πρόδωσες η ίδια πρώτη τον εαυτό σου όταν παράτησες τον εαυτό σου και αγνόησες τα θέλω σου για να προσκυνάς έναν άντρα και ένιωθες γυναίκα μόνο αν σου χωνε ξέρεις τι και που…. Die alone bitch. Sorry για την αθυροστομία αλλά εγώ προσωπικά ως γυναίκα προσβάλλομαι να βλέπω άλλες γυναίκες να πέφτουν στα πατώματα για έναν άντρα λες και ήρθε το τέλος του κόσμου και τελείωσε η ζωή τους μετά απ’ αυτό πόσο μάλλον να πρέπει να το διαβάζω.

-

i'm not saying Mario can choke but that's exactly what i'm saying <3

-

4.5 stars.

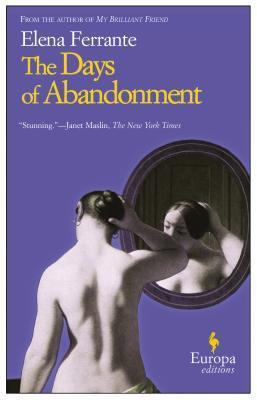

Elena Ferrante is an author I would never have checked out in the first place, if it wasn't for the fact that this book in particular was recommended to me by a bookish friend I trust. I mean let's be honest, that cover doesn't do this book any justice - it's terrible. And I know people say you should never judge a book by its cover, but most people I guarantee would have. This is why I implore all of you to read this book.

This is the depiction of one woman, Olga, and how she deals (or doesn't deal) with the fact that her husband has suddenly decided he is leaving her. As a reader, we are inside this woman's head throughout all of the 'days of abandonment', and it's a truly dark, bleak, and at times shocking place. We witness her erratic thoughts, her hallucinations, her desperation, her pain, her rage (which I believe was seen as quite controversial and shocking when the book was first published) - in short, you're drowning in her.

The writing and story is incredibly powerful, and as a reader I had very mixed emotions towards Olga as a character throughout. For the most part I did sympathise with her, as her situation was terrible and her husband was an ass, but on the other hand some of the things she said and did, the way she treated people... there was a lot to dislike about how she was dealing with the situation.

Despite being a relatively short novel, it's definitely not a quick read. At times you are focusing on the language that Ferrante gifts her character, and the way Olga articulates her thoughts is both harsh and beautiful (enough so that you are taken out of your reverie by a mere turn of phrase). At other times you are trudging through what feels like thick mud, and you feel like you'll never get out of it.

In short, read this book. Even if you think the plot sounds too 'girly', just read it. It's fantastic, and I'm still thinking about it several days after putting it down. I will most definitely be checking out all of Ferrante's other novels, no matter how bad the covers are. -

When I finished Shirley Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House two days ago, all I wanted to do as read another book exactly like that one. But the thing about Shirley Jackson's books is, there is no other book exactly like this. Next on my list was The Days of Abandonment. Not only is it the most recent Emily Books selection, but I've heard nothing but good things about Elena Ferrante in general. So I was looking forward to the book. But I did not think a novel about a middle-aged housewife in Turin abandoned by her husband would satisfy my craving for the ratcheting tension, emotional gut punches and eerie ambiguities I'd just experienced in Jackson's novel. How wrong I was. I stayed up all night gobbling up The Days of Abandonment.

I read a lot. I read a lot of good books. A lot of great books. And yet the word "brilliant" is one I rarely use to describe them. I didn't, for example, even think about it when I finished Ulysses earlier this year. But it flashed through my mind as I finished this one.

There's something so singular about its voice, its sentences, its structure, how most of the text is taken up by one terrible August day when Olga, her nagging 7-year-old daughter, her sick 10-year-old son and their maybe-poisoned German shepherd are literally trapped in their apartment. Talk about horror (there's even a ghost). The completely unsentimental, spookily realistic way Ferrante depicts a mother's relationship to and feelings about her children, her sexuality, her home. How the book becomes meta, but not, it's cheap to use that word, because narrative and thinking about how she narrates her life becomes essential to Olga's survival, to her sanity. And so this book is, in many ways, The Days of Abandonment is a middle-aged kunstlerroman, a portrait of an artist deferred, a woman returning to writing in her late thirties, after losing herself in marriage. -

I wanted to dive straight into the Neapolitan series but decided for a taste tester first with this novel and I’m so glad I did. Olga is abandoned by her unfaithful husband, leaving her for a much younger woman. This leaves Olga disoriented with rage and you feel her grasp slowly dissolving to catastrophic proportions it’s so cleverly written (also disturbingly funny at times) you feel the torment dripping off the pages. You feel her painful wrath and her emotional distress so alive you can feel it. While her husband is off living the life, shagging his new mistress and all but disappears from the scene she ends up questioning everything about her marriage, her sanity and her place as a mother.

Her anger keeps boiling and she can’t seem to control herself with erratic and random lashings towards the dog, the kids, the neighbours, the repairmen all become targets for her misplaced anger everything seeming to conspire against her. It’s easy to end up disliking Olga and her raging antics, she becomes completely deranged and her level of crazy is rather disturbing but I was also captivated as hell. I couldn’t look away, I even think some of her anger transferred to me. I was tetchy and irritable while reading it, feeling as if I was on the same emotional roller coaster. Slowly Olga attempts to put the broken pieces of her life back together again with varying degrees of success.

For all the misery this book breeds it’s also a novel that really lets you breathe in and absorb Olga fully, making no apologies for its ugly rawness. If this is a sign of Elena Ferrante’s writing abilities I can’t wait for my next fix! -

Ferrante wrote this in 2002 (English edition published in 2005). ‘Ties’ was written by Domenico Starnone in 2014 (English edition published in 2017). Seems to me like this — The Days of Abandonment —is written from the wife’s perspective, and ‘Ties’ is written from the husband’s perspective. The similarities really can’t be ignored. And the fact that Starnone is married to Anita Raja, the literary translator who was said to be the author Elena Ferrante in a report by the Italian investigative journalist Claudio Gatti in 2016, sure seems to me like there is relationship between the two novels (if not the two authors!). Anyhoo, I am glad that I read this in the same week that I read ‘Ties’...I really think they should be read together as they offer different perspectives from a marital separate/break-up. At least to me in this situation, the man walked away shirking a great deal of responsibility and the woman got the shaft.

So I say that the two books should be read together but I didn’t say in what mood or situation you should partake of reading ‘The Days of Abandonment’. I would advise:

• Try reading it in one sitting or at least as at few sittings as possible.

• If you are married don’t read it when you have had a recent spat with your spouse.

• If you are married don’t read it when you feel warm and fuzzy towards your spouse.

• If you are in a depressed mood, don’t read it.

• If you are in a cheerful mood, don’t read it.

Bon appetit!!! 🙂 🙃 😉

Reviews:

• (a review of both ‘Ties’ and The Days of Abandonment’):

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-...

•

https://heavenali.wordpress.com/2016/...

•

https://jacquiwine.wordpress.com/2014...

•

https://www.contemporarypsychotherapy... -

One April afternoon, right after lunch, my husband announced that he wanted to leave me.

And so begins Olga's descent into the heart of her own darkness. The Days of Abandonment packs a wallop of tension and cringe-inducing desperation into 188 pages of elegantly-rendered narrative. This isn't the story of a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown, this is THE nervous breakdown, in all its raw ugliness. We may tut-tut as we read Olga's hair-raising mayhem, but really, isn't this what we fear, in the wee hours, in our most vulnerable moments? As Shakespeare's Polonius declares in Hamlet, "Though this be madness, yet there is method in't."

The method is familiar: husband leaves wife for younger woman (in this instance, the very young daughter of a former family friend). Wife, who hasn't worked outside the home for many years, is left with the children, the house, the bills, and her own aging body. Disbelief, depression, anger, the divvying up of friends, the hope and fear of running into the ex and his paramour ensue. But Olga's madness? There is nothing expected in the way Elena Ferrante portrays Olga's domestic drama.

Olga's recounting of her freefall is detached and unsentimental. She tells it some years distant, but I also wonder if there is not some translation styling at work here. Although Ann Goldstein has translated all Ferrante's Europa Editions-published works, so I have to assume her tone is true to the author's own.

Contrary to that sense of emotional detachment, The Days of Abandonment is an intensely physical story. Olga is both obsessed with and horrified by her body, which at thirty-eight is showing the inevitable signs of age. She ruminates frequently about sex, reducing it to a purely animal act, torturing herself with images of her husband Mario, and his young lover, and then seducing her neighbor in a pathetic cry to recapture her crushed sexual self. Ferrante uses pain-an errant piece of glass in pasta sauce that pierces the roof of Mario's mouth; the threat of a mother to cut off her daughter's hands with sewing shears; a child's forehead smashing into the windshield to the sound of screeching car brakes--to frame Olga's sanity. It's almost as though pain is a stand-in for emotion: as long as Olga can envision pain and feel it, she'll be alright. She had reinforced locks put in the front door and at her lowest point, she struggles to open the locks, finally resorting to using her teeth. At one point, Olga asks her daughter Ilaria to poke her with a paper cutter if her concentration wandersI immediately pulled my mouth away from the key, it seemed to me that my face was hanging to one side like the coiled skin of an orange after the knife has begin to peel it. ...For a while I let myself sink into desperation, which would mold me thoroughly, make me metal, door panel, mechanism, like an artist who works directly on his body. Then I noticed on my left thigh, above the knee, a painful gash. A cry escaped me, I realized Ilaria had left a deep wound.

Most disturbing is the toll Olga's depression takes on her children and Otto, the family dog. The upsetting scenes of abuse and neglect may well kill any empathy you develop for Olga as an abandoned woman. But without them, Ferrante's narrative would simply be a mildly prurient glimpse into the life of the newly forsaken.

Olga wrestles with her post-abandonment identity, and her struggle is an alarm bell the author sounds relentlessly as she mocks the absurd circumstance of marriage that calls upon women to set aside their professions and their physical freedom, to attend to home, family, husband.I had carried in my womb his children; I had given him children. Even if I tried to tell myself that I had given him nothing, ... Still I couldn't avoid thinking what aspects of his nature inevitably lay hidden in them. Mario would explode suddenly from inside their bones, now, over the days, over the years, in ways that were more and more visible. How much of him would I be forced to love forever, without even realizing it, simply by virtue of the fact that I loved them? What a complex, foamy mixture a couple is. Even if the relationship shatters and ends, it continues to act in secret pathways, it doesn't die, it doesn't want to die.

"What a complex, foamy mixture a couple is..." Indeed. Foamy. An interesting choice of word. So sensual, evocative, invoking the fluids of sex, but also foaming at the mouth- a sign of madness, a rabidity of rage.

The Days of Abandonment is frank, gutting, oddly funny, and awfully sad. But it is not without hope, and throughout you are reminded that Olga survives her madness. Even swirling in its whirlpool, she has one hand above water, reaching, grasping.

Elena Ferrante's brilliance is withholding her judgment of her characters. She writes their truth and allows readers to create their own morality. Her writing, though not warm, is full of heat. The carapace of narrative rage cracks to reveal tender new skin beneath. -

My reviews of

Lacci and this book are

interconnected . The beginning of each are the same.

Elena Ferrante published her work in 2002, while Domenico Starnone (husband of Anita Raja, the person behind the Ferrante pen name) published his twelve years later, in 2014.

I read them in the wrong order because I did not know what I have written above. Lacci came into my view in the GR feed, and I picked it up because I was looking for short works in Italian. Ferrante I had been holding off until I felt a bit more comfortable with my Italian, and chose it over the Neapolitan tetralogy just in case.

*****

Ferrante's novel has a simple plot: a woman is abandoned by her husband (and I keep the passive voice) and the pages present the account of how she deals with this. The theme is more complex; it deals with a woman's identity.

I read it twice since it was the selection of my 'real' book club. This was a good thing since in my second reading I became more reconciled with the novel.

The title plays with the two possible meanings - one literal and the other both literal and metaphorical. The protagonist, Olga, sinks deep - abandons herself - during her crisis. She reaches a hell in her mind, losing volition and putting herself in denigrating situations. This was overdone and at times, particularly in my first reading, I laughed out loud a couple of times. Tragedy exaggerated can break its spell and become comic.

As a female reader for whom the exploration of identity issues would be of greater appeal I was disappointed at the end since the original equation of the identity of a woman seen as a function of her relationship with a man, is not really changed. Only the 'x' is substituted. There is no resolution then.

The whole crisis takes place in a short time period, which drew away from the veracity. May be the exaggeration of the deep cleave was a result and a compensation for this compression.

What I enjoyed most was Ferrante's success in creating a voice, and her rich language and fresh style; she combines a wealth of terms that overflow with some very effective and direct simplicity. The best indication of the extension of her language is that many of the words I looked up in the simple dictionary of my mobile: 'could not be found'.

This read ought to be followed by Lazzi to get a more faceted view.

And read more Ferrante too. Soon onto the tretralogy. -

"music is always soothing, it loosens the knots of nerves tied tight around the emotions"

*

"these women are stupid. Cultured women, in comfortable circumstances, they broke like knickknacks in the hands of their straying men. They seemed to me sentimental fools: I wanted to be different, I wanted to write stories about women with resources, women of invincible words, not a manual for the abandoned wife with her lost love at the top of her thoughts"

When we read a novel by an African-American author, we know there is good chance of racism showing up - not always, but there is a very good chance. When we read a novel by an author from backward classes, we are more likely to find the theme of untouchability or other such discriminating behavior. The same goes for women as well. And it is only to be expected, art and literature are nothing but expression taken to a higher form and even an animal screams when it is in pain. Nothing motivates the creation of art the way suffering does.It would be ridiculous to tell an author not to talk of his/her own sufferings in their works because it has grown old, we want something new. And it does often happen. Think of it, Imre Kertész, a concentration camp survivor and who later went on to win Nobel prize was told he shouldn't write about the Holocaust because the theme had grown old and nobody wants to read it. And, so, although it may sound like an old theme, I won't judge a book for it. Just because someone else has suffered it, and has written about it already, doesn't mean that the author should learn to shut up.

And this novel does much more, it warns all those sensitive souls not to give themselves away too much for those they love. Olga is sensitive:

"I hated raised voices, movements that were too brusque. My own family was full of noisy emotions, always on display, and I — especially during adolescence, even when I was sitting mutely, hands covering my ears, in a corner of our house in Naples, oppressed by the traffic of Via Salvator Rosa — I felt that I was inside a clamorous life and that everything might come apart because of a too piercing sentence, an ungentle movement of the body."

It is okay to be sensitive, but one must be assertive too. As is shown in Jane Eyre, a guy loses the respect of a woman who is not assertive enough. Olga lets herself belittled by her husband, forgives him when she catches him cheating. It also seems to be a warning to all those women who give up their careers for their families as to how vulnerable they are making themselves. Olga does that, it is probably not loss of her husband in itself which troubles her - "What a mistake, above all, it had been to believe that I couldn't live without him, when for a long time I had not been at all certain that I was alive with him.” But, it is the fact that "I had taken away my own time and added it to his to make him more powerful." Remember in 'The Handmaid's Tale' the first thing the new regime did was to take away from the women their financial agency.

And, so how will author make you feel his/her pain? (S)he is talking about a character who has gone through some intense anxiety for several days, and the author must make the reader feel it in a few moments, obviously just saying 'Olga suffered anxiety' is not enough. The first things authors, ever since Dostoevsky, have been doing is making their characters sensitive, perhaps too sensitive based on how you see it, and thus they are able to magnify the intensity of feelings they want to talk about. Ferrante does that.

The second thing they give a physical symbol to the emotional suffering. And thus Olga who would have felt helpless anyway is going through a very visible domestic crisis. The chaos in physical surroundings mirror her mental state.

"He was trying to communicate silently that, through his mysterious gift, he knew how to make meaning stronger, to invent a feeling of fullness and joy. I pretended to believe him and so we loved each other for a long time, in the days and months to come, quietly." -

Slightly spoilery

"Existence is a start of joy, a stab of pain, an intense pleasure, veins that pulse under the skin, there is no other truth to tell."

Abandonment. Loneliness. Rejection. How do we survive them? How does Olga survive, when her husband leaves her for a younger woman after fifteen years of marriage? By stepping outside of herself. She lets herself see. But is it only when we find ourselves tired of ourselves that we think to see outside of ourselves? And when we finally make this step, where are we willing to go and how far do we let ourselves see? Life is so complex, so tumultuous. It looks like we are always too far behind or moving forward too fast and never in the direction we need to. Sometimes we just need to stop and let ourselves breathe and think. Sometimes we need to act. Olga finds herself in a situation in which she needs to do both. Like many of us, she finds herself feeling like two different people. Her sensitive, contemplative self clings to the past, longing for a man who has never existed and hoping to restore a marriage which has never been there in the first place. And there is the practical, tough Olga, who knows that she needs to move forward. But where to? And how? It is scary sometimes to realize to what extent our character, the image we have built for ourselves, depends on the circumstances surrounding us. Are we no more than a bomb waiting to be activated, a disaster waiting to happen, gasoline needing just the lightest touch of fire? Are we bigger than our circumstances or are they bigger than us?

"We don’t know anything about people, even those with whom we share everything. The soul is an inconstant wind, a vibration of the vocal chords, for pretending to be someone, something."

"The most innocuous people are capable of doing terrible things."

"I was already no longer I, I was someone else, as I had feared since waking up, as I had feared since who knows when. Now any resistance was useless, I was lost just as I was laboring with all my strength not to lose myself,"

"I wanted to cut myself to pieces, I wanted to study myself with precision and cruelty…Where am I? Into what world did I sink, into what world did I re-emerge? To what life am I restored? And to what purpose?"

I would say that adversity shows us what we and those around us are made of. I have known for a long time that in each others’ eyes we are no more than chameleons. People perceive you as they perceive your circumstances. To them you are no more than a chameleon changing colours depending on the place it’s currently standing. Unconditional love and faith are rare gems. The sad thing about humans is that most of us bail when we stop liking the colours. It seems like to others, and often even to ourselves, we are no more than a sum of chances. We depend. Our happiness, our sorrow, our good and bad depend on that which is beyond our control. How does it happen so that we, intelligent, deep, sensitive creatures are dependant on the simple, soulless, mindless, dead chance? Are we no more than giants falling under the touch of the lightest feather? What is it about ourselves that we never lose, that we can always count on? What does Olga lose and gain after the loss of her previous life? What does she find out about herself and others? I believe that the desire and the will to understand and truly know others begins with the desire and will to understand and know ourselves. Olga, after forced by her circumstances, makes that step. Does she like what she discovers? Yes and no. Like most of us, she is complex, flawed. I certainly don’t accept and understand everything she does in the process, but I believe that were we capable of carrying ourselves through pain with impeccable strength and integrity, we wouldn’t have been vulnerable enough to develop a pain in the first place. I believe that it is not so much about whether and how much we fail (be it morally, professionally or personally). It is how we bear those failures that counts. Are we strong enough to admit them, learn from them and make peace with them? Olga isn’t perfect. In some moments she is gentle and generous, in others rude and insensitive. And in some she is downright violent and cruel. I believe her biggest strength is her willingness to forgive. To forgive herself and others. She thinks large, she cares, she understands. It is what raises her above her husband who, unlike her, in the end doesn’t find happiness in his new life. Olga does. She breaks free by letting herself fall, by letting herself break and being brave enough to pick up the pieces and rebuild herself into a different person. We are those who we are forced to be, by people and accidents, but we are also those we choose to be.

Read count: 1 -

One April afternoon, right after lunch, Olga’s husband announced that he wanted to leave her. He did it while they were clearing the table; the children were quarreling as usual in the next room, the dog was dreaming, growling beside the radiator. He told her that he was confused, that he was having terrible moments of weariness, of dissatisfaction, perhaps of cowardice. He talked for a long time about their fifteen years of marriage.

Then he assumed the blame for everything that was happening and closed the front door carefully behind him, leaving her turned to stone beside the sink.

Yes, right beside the bloody sink. As if that was a way of telling her, yeah, you stay there doing the dishes while the kids scream in the living room because I’m going now and move on with my life. Oh, god…

And from that moment by the bloody sink onwards, Olga’s life became a nightmare. Living in an apartment, and with two kids and a dog to look after, Olga soon realised that she wasn’t going to have enough time and space of her own to grieve.

What Elena Ferrante did here in her usual clear and precise prose, and by choosing to tell this story in such a visceral, raw and angry way was not only uncomfortably realistic, but also completely outstanding. It didn’t take long for Olga, who came across as a sweet, educated and good natured person, to start showing signs of being on the verge of a mental breakdown. Those signs, which I believe are often mistaken as symptoms of depression, were so well described that I often found myself laughing out loud. And not because I thought it was even in the slightest bit funny. On the contrary, I felt like one of those people who can’t control themselves properly and start laughing at the most inappropriate times or places, such as at the hospital or at a funeral. It was laughable, yes, but only because there was nothing else to do in the face of so much anxiety, loneliness and despair.

Oh my gosh, at some point the poor woman was sweating vulgarity, spitefulness and aggressiveness through every single pore of her body.

It really was painful to “watch”. Ugh!

After the halfway mark, and because this was told from Olga’s point of view, I’ll have to admit that I started to find it less and less “funny”, only to feel claustrophobically trapped inside her head (and her apartment) instead.

If you ever felt like you would never overcome a loss to the point of losing contact with your true self in an irrevocable way, then you really are going to relate to what Olga went through. And if you have been lucky enough to have never felt like that, I’m sure you will at least sympathise with her pain. The truth is, when something like this happens, and even if people eventually find a way back to the surface, they just know that things can never be the same again.

How can things go back to the way they were before when you know you were so close to breaking point? How can you completely let your defences down again, now that you are so painfully aware that there is a small gap that let so much darkness seep in so deeply before?

Life can be almost unbearably hard sometimes.

But then, as the saying goes, “no pain, no gain”, right? -

Όποιος αντί για την συγκλονιστική περιγραφή μιας ψυχολογικής κατάρρευσης, έμεινε στην μίρλα και τον μονόλογο της ηρωίδας, έχασε τον χρόνο του και την ευκαιρία να διαβάσει ένα εξαιρετικό βιβλίο. Αλλά ας τα πάρουμε τα πράγματα απ την αρχή.

Η Ferrante μπαίνει με το καλημέρα στο θέμα. Από την πρώτη κιόλας σελίδα μαθαίνουμε πως η Όλγα, μια 38χρονη μητέρα δύο παιδιών, εγκαταλείπεται από τον άνδρα της. Οι λόγοι είναι θολοί, με την ίδια ακόμα να ελπίζει σε ένα πισωγύρισμα, σύντομα όμως όλα ξεκαθαρίζουν με τον πιο αμετάκλητο τρόπο. Ο άνδρας της την άφησε για μια άλλη γυναίκα. Από την στιγμή της συνειδητοποίησης και έπειτα βλέπουμε την Όλγα να καταρρέει, να σκοντάφτει από το ένα λάθος στο άλλο και τελικά να καταλήγει σε μια μανιώδη κατάσταση, από αυτές που χρειάζονται άμεσα βοήθεια.

Η Ferrante, την οποία να υπογραμμίσω δεν έχω σε καμία μεγάλη εκτίμηση, σε αυτό το βιβλίο δείχνει ένα εντελώς διαφορετικό συγγραφικό πρόσωπο. Πιστή στην γυναικεία γραφή, όπως κακώς συνηθίζεται να λέγεται, καταπιάνεται με ένα θέμα σκληρό για κάθε άνθρωπο, άνδρα ή γυναίκα, την εγκατάλειψη από αγαπημένο πρόσωπο. Με πένα ατσάλινη περιγράφει την διαδικασία φθοράς της κεντρικής ηρωίδας σε πρώτο πρόσωπο. Σε βάζει μαζί της στις άβολες στιγμές της, σε βάζει δίπλα της να την παρατηρείς χαμένη.

Πράγματι στο βίβλο από ένα σημείο και μετά κυριαρχεί ένας ακατάπαυστος μονόλογος. Όσοι δεν έχουν έρθει σε επαφή με άτομα που πάσχουν από ιδεοψυχαναγκαστικές διαταραχές* περάσανε αυτό το κομμάτι στο ντούκου χάνοντας έτσι την ευκαιρία να απολαύσουν μια σαφή περιγραφή της κατάστασης αυτής. Όσοι το πρόσεξαν κάπως περισσότερο σίγουρα διέκριναν έναν φίλο, έναν συγγενή ή ακόμα και τον ίδιο τους τον εαυτό να μονολογεί, να φοβάται και να καταλήγει πάλι στο σκοτάδι.

Καταλήγοντας, το Μέρες Εγκατάλειψης, στο μεγαλύτερο μέρος του, είναι ένα άβολα ειλικρινές βιβλίο. Μου έκανε εντύπωση πως ακόμα και στις τελευταίες σελίδες η Ferrante δεν εγκατέλειψε αυτόν τον αρχικό σκοπό της. Βαθιά ανθρώπινο, εξαιρετικά σκληρό κατά στιγμές και σίγουρα ενδιαφέρον ανάγνωσμα. Προτείνεται σε όποιον είναι πρόθυμος να διαβάσει πίσω από τις γραμμές. Αυτό.

*Ψυχολόγος δεν είμαι, οπότε δεν είμαι απόλυτα σίγουρη για τον όρο που χρησιμοποίησα. Με βάση κάποιες εμπειρίες νομίζω ότι πρόκειται για τέτοιου είδους διαταραχή. -

Ferrantes novel is taut and precise,not necessarily plot driven.This is an exploration of the mental turmoil and anguish of a woman whose husband suddenly removes himself from the family home in Turin.Themes of abandonment,control,isolation,and recovery and much more.Very satisfying and succeeds wonderfully.Four Stars