| Title | : | Apology |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0865163480 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780865163485 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 127 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 400 |

The revised edition of this popular textbook features revised vocabulary and grammatical notes that now appear on the same page as the text, sentence diagrams, principal parts of verbs listed both by Stephanus page and alphabetically, word frequency list for words occurring more than twice, and complete vocabulary.

Apology Reviews

-

[Original review, Jan 11 2015]

Apology of Charlie Hebdo

To the Americans, who rule the world by brute military and economic force, while claiming they're doing it for our own good: fuck off.

To the Russians, who pretend they're not just the same as the Americans, except militarily weaker and less honest: fuck off.

To the Israelis, who take advantage of their American backers to enslave and torture the Palestinians: fuck off.

To the Muslims, who react to the exploitation and torture inflicted on them by doing the same thing to their women: fuck off.

To the Germans, who want us to believe that none of them had anything to do with the Third Reich: fuck off.

To the French, who were all too happy to collaborate with the Nazis when the opportunity presented itself: fuck off.

To the Catholic Church, who says it spreads peace and understanding while actually supporting intolerance and oppression: fuck off.

To the right-wing people who don't read us and say we're a bunch of puerile amateurs: fuck off.

To the left-wing people who read us and think that posting our cartoons on Facebook is a substitute for action: fuck off.

To anybody we've omitted from the above list: fuck off.

We understand that you'd like to kill us. We do our best to be a royal pain in the ass to everyone. We are stupid, vulgar and disrespectful. But when you do kill us, as we know you will, you will regret it. It's not often you find people who are quite as thoroughgoing a pain in the ass as we are.

Now we must part, we to die and you to live. We'll leave you to think about who's got the better deal.

___________________________________

[Update, Sep 17 2015]

To the people who've never read us and don't even know French, but still think they understand what our cartoons are about better than we do: fuck off.

___________________________________

[Update, Nov 8 2015]

To the officials at the Kremlin who called us "blasphemous" because we were targeting Russians as well as Muslims: fuck off.

___________________________________

[Update, Sep 4 2017]

To the Americans who don't understand that our cover this week might possibly be ironic: fuck off.

___________________________________

[Update, Mar 14 2021]

To the sensitive entitled snowflakes of the Royal Family who think it's not enough to get tens of millions of pounds a year from the British taxpayer for basically doing nothing, they want their respect too: fuck off. -

The trial of Socrates is reminiscent of other historical and literary practices. The Apology of Socrates, that of Plato (there is another one), is a strong and philosophical text. Easy to read, with style specific to Plato (a marvelous playwright), it remains a text of access to the thought of "Socrates" and philosophy itself.

-

Double Jeopardy

“Be sure that if you kill the sort of man I say I am, you will not harm me more than yourselves.”

***

“On the other hand, if I say that it is the greatest good for a man to discuss virtue every day, testing themselves and others — for the unexamined life is not worth living for men, you will believe me even less.”

Socrates, of The Apology is an eloquent figure who is an unrivaled guide to the good life – the thoughtful life, and he is as relevant today as he was in ancient Athens. The Socrates presented here, cruder and perhaps more self-absorbed than in the other dialogues could still be an important key to the entire Platonic corpus, tying together many of the disparate themes and apparently contradictory conclusions of the other dialogues.

The Apology is a bold and determined argument in favor of Socrates and of the life he represents; it is also a straight conviction of the ‘democracy’ that convicted him, convicting themselves in the process. In addition to being a celebration of Socrates, the Apology serves as a crucial introduction to Plato’s own thinking. What it represents above all is philosophy as Socrates (or Plato, if we want to be fastidious about it), understood and wished to promote it. The Apology is the introductory course.

The traditional English title, ‘The Apology’ does little justice to the content of this dialogue. The Greek ‘apologia’ means ‘defense’ and not the modern ‘apology’ as translations render it, and that is what Plato undertakes here - to defend Socrates as well as he can against the charges that were leveled against him, the charges for which was eventually convicted. But the work is not only, or even primarily, a defense against the specific charges on which Socrates stood trial. By setting those charges in the wider context of morality and the meaning of life, Plato in this “Apology” provides a rationale for the whole Socratic way of life, and thus of a defense of philosophy itself.

The Apologia of Socrates

The Apologia comprises two main components (one minor speech, on the death penalty, is omitted from discussion in this review):

1. Socrates’ main defense (17a-35d)

2. Socrates’ address to the jury, after being sentenced to death (38c-42a)

— In effect, The Plea & The Final Statement.

Socrates starts off logically, breaking up his accusers into the proximate and the ultimate accusers: the ones who have brought the charge against him being the ‘new’ ones and the ones like Aristophanes who have slandered him for years now being the ‘old’ ones. He makes and important point here about the absurdity of being given only such a limited amount of time to defend against charges that were propagated and insinuated into the jury’s beliefs over so many years. This calls to mind the trial-by-media that is so popular today and the issue of how much the judges of today can stay apart from pre-conviction by automatic-infusion of prejudice in popular cases.

Socrates carries on this vein and presents his arguments as an imaginary dialogue between him and his chief accuser (Meletus), ridiculing him and showing up the anti-logic of the accusations. Here, Socrates makes Meletus seem almost like a straw man, against whom victory is won too easily to be convincing - and this is often taken as a fault in Plato’s writing itself. But we need to look a bit more closely at Plato's strategy. The ‘primary’ charges of atheism and religious innovation are answered superficially because they were themselves superficial, a mere front to conceal the true motives of the prosecution. Socrates refers directly to this in the important opening section of his speech, where he replies to his 'earlier accusers'. It is these earlier accusers, who were exposed by his rational method to be following a morally subversive lifestyle that wants to get rid of him. The proximate Meletus is a mere cover to this ultimate reason for the trial. Socrates shows this cowardly subterfuge well-deserved contempt.

But we soon realize that he moves on from this refutal of charges, which he obviously considers to be frivolous and not worth wasting the time of the Athenian public on (In democratic Athens, juries were randomly selected representatives of the whole people. Hence, as Socrates makes clear, he is addressing the democratic people of Athens). He instead utilizes the bulk of his speech to concentrate on explaining what he does, why he does it and how in fact it benefits the city as a whole. Staying true to his life’s mission to the last breath.

Hence, this dialogue starts first, of course, as a defense, then it turns into a description of the philosophical life, as embodied by Socrates. This description then evolves into, and becomes indistinguishable from, an exhortation to everyone – whether jurors, the people of Athens or modern readers – to live philosophically. And finally it serves as a primer on Plato’s own philosophy and writing - as the later dialogues mimic the ideas, methods and themes ‘Socrates’ lays out in this account of his life and goals.

The Death of Socrates

In death, Socrates gives us another important clue towards understanding Platonic thought. Plato speaks at length in The Republic about how men’s conception of death has to be altered for them to be able to live courageously. As long as they fear death, they will not be able to live with courage. Here, in death, Socrates compares himself to the fear-less hero Achilles, who embraced death in spite of a direct prophesy that foretold death as the outcome of his victory. This is a very important comparison and worth dissecting a bit:

Why does Achilles not fear death? Ordinary people can only perceive this as a heroic abnegation of life for some higher principle. This makes that sort of courage unattainable to most. As long as you care for earthly possessions and expect death to be bad, you will never have the courage to do the right things even in the face of death. Crucially, Socrates points out that both these assumptions are baseless. He asks us how we know that death is bad and that life’s possessions are good. Instead he seems to be saying that our fear of death and lack of courage arises from a fear of what will happen after death. This though directly connects to the Republic where Socrates wants his city’s mythologies to be modified so that a pleasant life awaits us after death, hence the people of the Republic can be courageous without having to call on Achilles-like heroism, or on Socrates-like Temperance.

Hence, in The Apology Socrates asks the best of us - to choose between Heroism and Renunciation - an impossible ask; but a more mature Plato in The Republic tells us that he will take away the source of our fear, that is the only way he can expect men to be courageous.

Double Jeopardy

True to the last to his philosophical calling, Socrates addresses his plea and his last statement not to the Jury alone but to the entire Athenian public, and even, we can say, to the entire human race. He required of us that we think, honestly and dispassionately, and decide the truth of these charges by reasoning from the facts as they were.

This was Socrates’ final challenge: to care more for our minds, our power of reason, than for our luxury and comfort, undisturbed by the likes of “Gadflies” like him, disturbing our slumbers. We can see then that The Trial and Death of Socrates is in fact The Trail and Death of Reasoned Opinions that challenge the established order of comfort and luxury, and has been reenacted many many times since then and to our day.

In an ironic case of double jeopardy, Socrates is still on trial for the same offense. Seen in this light, as Plato wants us to see it, the failure is ours, as much as the ancient Athenians.

“So I am certainly not angry with those who convicted me, or with my accusers.

This much is all I ask of my accusers: when my sons grow up, avenge yourselves by causing them the same kind of grief that I caused you, if you think they care for money or anything else more than they care for virtue, or if they think they are somebody when they are nobody.

Reproach them as I reproach you, that they do not care for the right things and think they are worthy when they are not worthy of anything. If you do this, I shall have been justly treated by you, and my sons also.

Now the hour to part has come. I go to die, you go to live. Which of us goes to the better lot is known to no one.”

-

Platón nos desglosa en este texto el juicio oral al que fue sometido Sócrates, acusado de corromper a la juventud y de adorar a otros dioses.

Básicamente, es un monólogo argumentativo en el que Sócrates plantea su defensa ante sus acusadores y los jueces.

-------------------------

In this text Plato describes the oral trial to which Socrates was subjected, accused of corrupting the youth and worshipping other gods.

Basically, it is an argumentative monologue in which Socrates presents his defence to his accusers and the judges. -

Θανάτωσαν τον Σωκράτη.

Θανάτωσαν το αρχαίο ελληνικό πνεύμα.

«Γιατί το να φοβάται κανείς το θάνατο, ω άνδρες Αθηναίοι, δεν σημαίνει τίποτε άλλο ή το ό��ι νομίζει πως είναι σοφός ενώ δεν είναι. Σημαίνει δηλαδή πως νομίζει ότι ξεύρει πράγματα που δεν ξεύρει. Γιατί τι είναι θάνατος, κανείς βέβαια δεν ξεύρει, μπορεί να είναι το μέγιστο από τα καλά στον ��νθρωπο, τον φοβούνται όμως σα να ξεύρουν καλά πως είναι το μέγιστο των κακών».

«Μήπως δεν είναι αυτό δύσκολο, το θάνατο κανείς να αποφύγει, αλλά πολύ δυσκολότερο την κακία. Γιατί αυτή γρηγορότερα από το θάνατο τρέχει».

«Αλλά ώρα είναι βέβαια να πηγαίνουμε πλέον, εγώ μεν για το θάνατο, εσείς δε για τη ζωή. Ποιοι όμως στο καλύτερο πηγαίνουμε από τους δυο μας, άδηλο σε όλους. Το ξεύρει μόνον ο θεός». -

“Socrates is guilty of busying himself with research into what’s beneath the earth and in the heaven and making the weaker argument the stronger and teaching the same things to others”

So Socrates is guilty of expanding his mind and teaching his discoveries to his students. Such a terrible man isn’t he, to try to learn more about the world and the existence of mankind? Is this cause of execution, free thinking and questioning the doctrines fed to us? Plato himself was next to be accused; thus, he delivers this speech, this argument, just to show how corrupt society is.

He starts by explaining just how he is going to deliver it. He has been accused of persuading people with his fancy words and his glib rhetoric, so he endeavours to change his approach. His accusers say that people aren’t following the content of his speech, but have become enamoured by the magnificence of his oration. Therefore, Plato is going to make this very basic. He is going to present a simple argument in very simple words just to prove that this surface level slander is false. He’s not going to persuade his audience, but give them the most basic of facts: they can make their own mind up. He’s not going to patronise his audience.

And thus follows his defence of his teacher, and a channelling of his master’s mind. Socrates was dangerous to the Greek state. Free thinking is wonderful, but if it questions the ruling body, and the tools they use to rule, then it’s dangerous. Indeed, his atheism, or supposed atheism, was considered a risky business, one that could easily spread. But, the real problem as his individuality and the power his following commanded. He opened the minds of his students, allowed them to think and philosophise, and he died for it. And he, being the embedment of civil obedience, approached his fate with courage. He didn’t run from Athens like many would have. To his mind, he was innocent. So why flee?

This was an interesting read. I find myself drawn to woks of ancient Greece lately. I have a stack of Tragedy sat on my book shelf (Sophocles, Euripides and Aeschylus). But this was a little dry in places. It lacked the passion that Plato deliberately avoided, and as a result some of it was a trifle mundane to read. I still want to read Republic though.

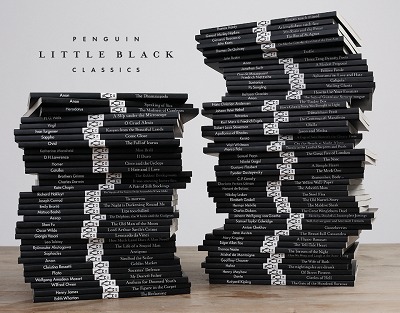

Penguin Little Black Classic- 52

The Little Black Classic Collection by penguin looks like it contains lots of hidden gems. I couldn’t help it; they looked so good that I went and bought them all. I shall post a short review after reading each one. No doubt it will take me several months to get through all of them! Hopefully I will find some classic authors, from across the ages, which I may not have come across had I not bought this collection. -

This is perhaps the most iconic of Plato’s works, the closest thing that philosophy has to a Sermon on the Mount. And just as with our Biblical narratives, the dialogue presents a historical difficulty. To what extent is this speech fact, and to what extent invention? The only other record we have of the trial is from Xenophon, who wasn’t even there. Plato was there—or at least he asserts that he was—and yet it beggars belief that the young, would-be amanuensis could retain the entire speech in his mind after one hearing, or that he could write it down with tolerable accuracy as the events unfolded. It seems far more likely (to me at least) that this speech is more or less a fabrication made well after the fact, attempting to preserve the flavor and impression of Socrates’ final speech but not the exact words themselves.

All speculation notwithstanding, the essential facts are preserved: Socrates was accused of denying the gods and of corrupting the youth, made a bold and waggish defense of himself, was convicted, refused to mitigate the consequences, and triumphantly accepted the death penalty. Yet what really emerges from this speech is not a record of events but the portrait of a man.

Here Plato reveals himself to be a writer of the highest order. Fact or fiction, Plato’s Socrates is one of the great characters of literature. Though Socrates’ life is at stake, he does not falter for a moment. He treats the accusations with amusement, dismissing them with playful arguments that reveal his absolute indifference to the outcome. Far from bowing and scraping to preserve his life, Socrates flaunts his superiority to his accusers, couching his boasts in an ironical humility. He is a man in perfect control of himself and in perfect peace with the world.

Even if the real Socrates was truly this remarkable, it would have taken a writer of exquisite talent to effectively render him in prose. And if this is largely Plato’s invention, we must rank him along with Shakespeare, for Socrates utters now-famous phrases nearly as quickly as Hamlet. Western philosophy could not have asked for a more rousing beginning. -

آپولوژی افلاطون

سال ۳۹۹ پیش از میلاد مسیح سقراط متهم شد به فاسد کردن جوانان و بی خدایی

سقراط در دادگاه آتن حاظر شد و با نمایشی با شکوه و پرسش سوال های هوشمندانه از بی گناهی خودش دفاع کرد و حاضر نشد مانند سایر متهمین آتنی با گریه و زاری و آوردن بچه های خود به دادگاه مظلوم نمایی کند

در نهایت با رای گیری و اختلاف تنها سه رای مجرم شناخته شد

طبق رسم به متهم اجازه داده شد تا مجازات خود را به قاضی ها پیشنهاد دهد

سقراط پس از حکم میگه :

ﺑﻪ ﻫﺮ ﺣﺎل ﭼﻮن ﮔﻨﺎﻫﯽ از ﻣﻦ ﺳﺮ ﻧﺰده اﺳﺖ ﭼﮕﻮﻧﻪ ﭼﺸﻢ دارﯾﺪ ﮐﯿﻔﺮي ﺑﺮاي ﺧﻮد ﭘﯿﺸﻨﻬﺎد ﮐﻨﻢ؟ ﮔﺬﺷﺘﻪ از اﯾﻦ، از ﮐﯿﻔﺮي ﮐﻪ ﻣﻠﺘﻮس ﭘﯿﺸﻨﻬﺎد ﮐﺮده اﺳﺖ، ﺑﺎﮐﯽ ﻧﺪارم . زﯾﺮا ﻧﻤﯽ داﻧﻢ آن ﮐﯿﻔﺮ ﺑﺮاي ﻣﻦ ﺧﻮب اﺳﺖ ﯾﺎ ﺑﺪ . ﭘﺲ ﻣ ﻮﺟﺒﯽ ﻧﻤﯽ ﺑﯿﻨﻢ آن را ﺑﺎ ﮐﯿﻔﺮي ﻋﻮض ﮐﻨﻢ ﮐﻪ ﺑﺪي آن ﺑﺮاي ﻣﻦ ﻣﺎﻧﻨﺪ آﻓﺘﺎب روﺷﻦ اﺳﺖ . ﻣﺜﻼ ﭘﯿﺸﻨﻬﺎد ﮐﻨﻢ ﮐﻪ ﻣﺮا در زﻧﺪان ﻧﮕﺎه دارﯾﺪ؟ زﻧﺪﮔﯽ در زﻧﺪان ﺗﺤﺖ ﻓﺮﻣﺎن زﻧﺪاﻧﺒﺎن چه ارجی دارد؟

جزاي ﻧﻘﺪي ﭘﯿﺸﻨﻬﺎد ﮐﻨﻢ ﺑﺎ اﯾﻦ ﻗﯿﺪ ﮐﻪ ﺗﺎ آن را ﻧﭙﺮداﺧﺘﻪ ام در زﻧﺪان ﺑﻤﺎﻧﻢ؟ ﻣﻦ ﻣﺎﻟﯽ ﻧﺪارم . از اﯾﻦ رو ﺗﺎ ﭘﺎﯾﺎن ﻋﻤﺮ در ﺑﻨﺪ ﺧﻮاﻫﻢ ﻣﺎﻧﺪ . ﭘﺲ ﻣﺠﺎزات ﺗﺒﻌﯿﺪ ﭘﯿﺸﻨﻬﺎد ﮐﻨﻢ؟ ﮔﻤﺎن ﻣﯽ ﮐﻨﻢ ﺷﻤﺎ ﻧﯿﺰ ﺑﻪ ﭘﺬﯾﺮﻓﺘﻦ اﯾﻦ ﭘﯿﺸﻨﻬﺎد راﻏﺐ ﺗﺮ ﺑﺎﺷﯿﺪ . وﻟﯽ آﺗﻨﯿﺎن، دﻟﺒﺴﺘﮕﯽ ﺑﻪ ﺣﯿﺎت ﻣﺮا ﭼﻨﺎن دﯾﻮاﻧﻪ ﻧﮑﺮده اﺳﺖ ﮐﻪ ﮔﻤﺎن ﮐﻨﻢ ﺑﺎ اﯾﻨﮑﻪ ﺷﻤﺎ ﻫﻤﺸﻬﺮﯾﺎن ﻣﻦ ﻧﺘﻮاﻧﺴﺘﯿﺪ ﺳﺨﻨﺎن ﻣﺮا ﺗﺤﻤﻞ ﮐﻨﯿﺪ ، ﺑﯿﮕﺎﻧﮕﺎن ﺗﺎب ﺷﻨﯿﺪن آﻧﻬﺎ را ﺧﻮاﻫﻨﺪ داشت ﺑﻨﺎﺑﺮاﯾﻦ ﭼﻨﯿﻦ ﭘﯿﺸﻨﻬﺎدي را از ﻣﻦ ﭼﺸﻢ ﻣﺪارﯾﺪ

در پایان سقراط بهای ناچیز ۳۰ مینه ای برای آزادی خودش پیشنهاد میکنه و دادگاه اون رو قبول نکرده و حکم مرگ با زهر را برای سقراط صادر میکند

شرح حال دادگاه و دفاعیه سقراط توسط بسیاری نوشته شد که معروف ترین آن ها آپولوژی افلاطون و آپولوژی ��زنفون نام دارند

در آپولوژی افلاطون دفاعیه سقراط به طور کامل تر نوشته شده و دفاعیه سقراط در دادگاه به طور کامل شرح داده شده

ولی گزنفون در آپولوژی خودش در عوض چیز های جا مانده ای که افلاطون در سه گانه سقراط خود جا انداخته است را نوشته است که حجم زیادی هم ندارد -

دوستانِ گرانقدر، «افلاطون» در این رساله مراحلِ دادگاهی کردنِ زنده یاد «سقراطِ بزرگ» و دفاعیاتِ وی در دادگاه در برابرِ مردمِ بیخرد و دهان بین همچون ملتوس و آنیتوس را نوشته است.. به قولِ خودِ سقراط، پیش از این نیز کسانی همچون پالامدس و آیاس نیز با رأیِ ظالمانۀ چنین مردمی، به سویِ مرگ رفته اند

مردمِ نادانی که با تحریکِ عده ای سفسطه گر گفتند سقراط با سخنانش، مغزِ جوانانِ ما را فاسد کرده است.. شکایتی که از سقراط شده بود بدین ترتیب بود که: سقراط رفتاری خلافِ دین پیش گرفته و در پیِ آن است که به اسرارِ آسمان و زمین پی ببرد.. باطل را حق جلوه میدهد و اینکار را به دیگران نیز می آموزد

عزیزانم، ارزشِ این کتاب، در همان دفاعیاتِ سقراط است که فنِ سخنوری را به نوعی آموزش میدهد .. در زیر به انتخاب، بخش هایی از این رساله را برایِ شما عزیزان، مینویسم

---------------------------------------------

کسانی که بیش از همه به دانایی شهره هستند و از نادانیِ خویش خبر ندارند، زبون تر از کسانی هستند که شهرتی به دانایی ندارند و به نادانیِ خود آگاه هستند

**********************

آنان میتوانند مرا بکشند، یا از کشور برانند، یا از حقوقِ اجتماعی محروم سازند.. شاید این امور در نظرِ دیگران بدبختیِ بزرگی به شمار آید، ولی در نظرِ من چنین نیست. بدبخت کسی است که مانندِ ایشان بکوشد تا کسی را بر خلافِ عدالت از میان بردارد

**********************

آتنیان، دلبستگی به حیات مرا چنان دیوانه نکرده است که گمان کنم با اینکه شما همشهریانِ من نتوانستید سخنانِ مرا تحمل کنید، بیگانگان تابِ شنیدن آنها را خواهند داشت. بنابراین چنین پیشنهادی را از من چشم مدارید. محال است من این اندیشه را به خود راه دهم و برایِ چند روز زندگی در این سالخوردگی، سرگردان شوم و هر روز راهِ شهری دیگر پیش گیرم. زیرا نیک میدانم که به هر شهر روی آورم، جوانانِ آنجا مرا حلقه وار در میان خواهند گرفت و به سخنانِ من گوش فرا خواهند داد. اگر آنان را از خود برانم خودِ آنان به تبعیدِ من کمر خواهند بست و اگر نرانم، پدران و خویشانشان مرا از شهرِ خود خواهند راند

**********************

آتنیان، با این ناشکیبائی نامِ نیکِ خود را به باد دادید و بدخواهان و خرده گیران را گستاخ ساختید. زیرا از این پس عیب جویان به سرزنشِ شما برخواهند خاست و خواهند گفت مردِ دانایی چون سقراط را کشتید.. هرچند من از دانایی بهره ای ندارم، ولی بدگویان شما خلافِ این را ادعا خواهند کرد و حال آنکه اگر اندکی درنگ کرده بودید مقصود شما حاصل میشد. زیرا میبینید که من پیرم و پای بر لبِ گور دارم. در این نکته روی سخنم با همه نیست بلکه با کسانی است که رأی به کشتنِ من داده اند. اینک به آنان میگویم: شاید گمان میبرید علتِ محکوم شدنِ من ناتوانیم از گفتنِ سخن هایی است که اگر میگفتم از این مهلکه رهایی مییافتم. ولی چنین نیست. راست است که سببِ محکوم شدن من ناتوانیم بود، ولی نه ناتوانی در سخن گفتن. بلکه من از بی شرمی و گستاخی و گفتنِ سخنانی که شما خواهانِ شنیدنش بودید ناتوان بودم و نمیتوانستم لابه و زاری کنم و سخنانی به زبان آورم که شما به ش��یدنِ آنها از دیگران خو گرفته اید و من در خورِ شأنِ خود نمیشمرم. نه هنگامِ دفاع از خود آماده بودم تا برایِ گریز از خطر به کاری پست تن در دهم و نه اکنون از آنچه کرده و گفته ام پشیمانم. بلکه مردن پس از آن دفاع را، از زندگی با استرحام و زاری برتر میشمارم. زیرا سزاوار نمیدانم که آدمی چه در دادگاه و چه در میدانِ جنگ از چنگالِ مرگ به آغوشِ ننگ بگریزد. اگر روا باشد که انسان برایِ رهایی از خطر به هر کردار و گفتاری توسل جوید، در میدانِ جنگ نیز بسا پیش می آید که با انداختنِ سلاح و سر فرود آوردن در برابرِ دشمن به آسانی میتوان از مرگ رهایی یافت. در برابرِ خطرهایِ دیگر نیز وسیلۀ رهای�� بسیار است.

---------------------------------------------

امیدوارم این ریویو در جهتِ آشنایی با این کتاب، مفید بوده باشه.. یادِ سقراط همیشه گرامی باد

«پیروز باشید و ایرانی» -

Apologia is Plato’s account of Socrates’ self-defense speech in front of the judges who accused him of not believing in gods and corrupting the youth with his ideas.

-

"Αλλά τώρα πια είναι ώρα να φύγουμε, εγώ για να πεθάνω, κι εσείς για να ζήσετε. Ποιοι από εμάς πηγαίνουν σε καλύτερο πράγμα, είναι άγνωστο σε όλους εκτός από το Θεό."

-

This little ‘book’, a mere conversation actually, is the source of so many excellent quotes as to be indispensable to our Western heritage. I was reading a few to my dear husband the other night and he wanted me to send them to him. Sadly, we—as a society—want to expunge this type of literature from our children’s education because it was written by ‘dead white men’.

Oh foolish people! But then, that is also what Socrates died for—men’s fear of the Truth. It was the same back in Athens when he died. As was written by another wise man, ‘there is nothing new under the sun’.

Here are just a few of my favorite quotes from this wonderful ‘apology’ for Truth:

‘Someone will say: And are you not ashamed, Socrates, of a course of life which is likely to bring you to an untimely end? To him I may fairly answer: There you are mistaken: a man who is good for anything ought not to calculate the chance of living or dying; he ought only to consider whether in doing anything he is doing right or wrong—acting the part of a good man or of a bad. … For wherever a man's place is, whether the place which he has chosen or that in which he has been placed by a commander, there he ought to remain in the hour of danger; he should not think of death or of anything but of disgrace.’

‘For the fear of death is indeed the pretense of wisdom, and not real wisdom, being a pretense of knowing the unknown; and no one knows whether death, which men in their fear apprehend to be the greatest evil, may not be the greatest good.’

‘I would rather die having spoken after my manner, than speak in your manner and live. … The difficulty, my friends, is not to avoid death, but to avoid unrighteousness; for that runs faster than death.’

‘If you think that by killing men you can prevent someone from censuring your evil lives, you are mistaken; that is not a way of escape which is either possible or honorable; the easiest and the noblest way is not to be disabling others, but to be improving yourselves.’

And my favorite, ‘…the unexamined life is not worth living.’

Indeed! It is not that we become navel-gazers, but that we realize Whose we are and give ourselves over to love of Truth.

September 27, 2017: Read this many years ago ... cannot remember when. Time for a reread. -

¡Oh, atenienses! ¿Era Sócrates un grano en el c... para muchos de vosotros? Por supuesto, y se enorgullecía de serlo. Qué maravilla de discurso sobre la dignidad, la justicia, la sabiduría y la muerte, cuyo misterio estaba a punto de descubrir.

“Pues nadie conoce la muerte, ni siquiera si es, precisamente, el mayor de todos los bienes para el hombre, pero la temen como si supieran con certeza que es el mayor de los males.”

Platón nos pinta de cuerpo entero a su maestro Sócrates en su defensa final, con un discurso conmovedor para los oyentes (y los actuales lectores) conminando a los Jueces a que sigan buscando la verdad y la integridad, en una postura digna e implacable.

"¿Cómo no te avergüenzas de no haber pensado más que en amontonar riquezas, en adquirir créditos y honores, en despreciar los tesoros de la verdad y de la sabiduría y en no trabajar para hacer tu alma tan buena como pueda serlo? "

Da mucha vergüenza agregar algo más después de eso. Magnífica. -

I always wonder about the skills of these highly intellectual, talented people of Ancient times. It's a delight to read Socrates' legal defence and you can feel his charisma through the words. Such a shame that there are only few (if at all) who can compete on his level of logic, ethos and pathos. And it's such a shame never to be able to witness a "performance" of his speech since the performance itself with its gesture and voice also has a huge impact on the audience.

-

This is one of the best works of philosophy or literature ever written. It is Plato's version of Socrates's defense at his trial. The word "apology" here means defense. Socrates is on trial for his life for blasphemy and for corrupting the youth of Athens. He very easily leads his primary accuser, Meletus, into contradictions. And he tries to explain to the jury and to the spectators how it is that he gained a reputation as a wise man among some, and a villain among others. One of Socrates's admirers went to the Oracle at Delphi (which was thought to be pro-Spartan) and asked the priestesses there if anyone in Athens were wiser than Socrates. The answer was no. Socrates, on hearing this, claims to have been incredulous. "I said to myself, 'What can the God mean? And what is the interpretation of this riddle? For I know that I have no wisdom..." And so Socrates says that he decided to inquire among his fellow Athenians to fine one wiser than himself and prove the Oracle wrong. He went to the poets and politicians and artisans, and failed to find anyone with any real wisdom. And he reluctantly concluded that the Oracle was right, that even though he knew that he did not really know anything, he was at least aware of his ignorance, and so was better off than other Athenians, who were ignorant even of their ignorance. But in the process, he and his young admirers embarrassed many vain men by exposing their ignorance, and Socrates argues that this is the source of their enmity toward him. And Socrates rather amusingly compares his own efforts to the famous labors of Herculues, a move that could not fail to further antagonize his enemies, since Hercules was one of the greatest heros of Greek myth. He also later compares himself to Achilles, another great Greek hero.

In his defense, Socrates offers the most beautiful and powerful defense of philosophy and the life of virtue ever given. "I do nothing" he says, "but go about persuading you all, old and young alike, to take no thought for your persons or your properties, but first and foremost to care about the greatest improvement of the soul. I tell you that virtue is not given by money but that from virtue comes money and every other good of man."

Socrates courageously refused to concede any guilt, and even antagonized the jury by calling himself a gadfly sent by God to stir Athens from its dogmatic slumber, that is, a benefactor to the state who deserves public pay, rather than punishment. So they convicted him and sentenced him to death. This was, as he had predicted, a permanent stain on Athens.

Everyone ought to read this dialogue, not once but many times. It will hopefully spur the reader to examine his own life, for as Socrates says, "the unexamined life is not worth living." -

“Well, gentlemen, for the sake of a very small gain in time you are going to earn the reputation – and the blame from those who wish to disparage our city – of having put Socrates to death.”

It is quite normal, I think, to read the Apology and feel as though Socrates has blundered horribly in judgment – he has said the very things that will drive him to the grave. After hearing of the declaration of the Oracle of Delphi that there is no one wiser than him, he has taken it upon himself to ensure the verity of this statement. This has led to disgruntlement among the masses and a court trial. There are multiple opportunities during this defence for Socrates to gain a foothold and paint himself as a favourable citizen to the jury – he does not take a single one of these opportunities. In fact, he did not care at all whether he was able to “mind his manners” during the trial – he would have wanted to die a death that one could be proud of. Well… he succeeded. And thus, slowly but surely, we began to look at philosophy and its pursuit as the art of learning how to die. -

Bir kere daha anladım ki yalan, iftira insanoğlunun mayasında var. Milattan önceki yıllarda dahi bilge insanlar otoriteler tarafından tehdit olarak görülüyordu. Sokrates’in hazin öyküsünü, kitabı okumadan önce de biliyordum ama savunmasını okuyunca çok etkilendim ve üzüldüm.

Bu arada kitabın oldukça uzun bir girişi var( yaklaşık 40 sayfa), savunmayı okumadan önce Sokratesin felsefesi hakkında kısaca bilgi sahibi olmamızı sağlıyor. Sokrates’in çok doğru bulduğum ve yaşam felsefesini özetleyen bir sözüyle yazımı tamamlamak istiyorum.

“Anladım ki kendilerini bilgili olarak satanlar gerçekte en bilgisiz olanlardır. “ -

دلم واسه خووندن تنگ شده.

دوباره تو عید شروع میکنم به خووندن 😍 -

رساله ی دفاعیه ی سقراط در برابر دادگاه آتن که او را به اتهام "آوردن خدایان جدید" و "گمراه کردن جوانان" به محکمه کشیده بودند. بعضی از قسمت های دفاعیه عالی است.

دادگاه با اکثریت 60 به 40 سقراط را مخیر کرد که مجازات مرگ را بپذیرد یا جریمه ی مالی بپردازد. افلاطون که گویا ثروتمند بوده، به سقراط پیشنهاد کرد جریمه بپردازند و خودش حاضر شد مبلغ بسیار زیادی بدهد؛ ولی سقراط، طبق رفتار معمولش (به تمسخر گرفتن همه چیز) پیشنهاد بسیار ناچیزی برای خریدن جان خودش داد. این پیشنهاد ناچیز، به هیئت منصفه برخورد و این بار، با اکثریت 90 به 10 درصد سقراط را به مرگ محکوم کردند. پس از چند روز، با نوشیدن جام زهر حکم اجرا شد.

(درصد اکثریت دادگاه تقریبی است. مقدار دقیقش را به یاد ندارم.) -

After four years, I finally managed to reread this thing, and I'm glad that I did. It really goes to show that not all of my remaining brain cells have died during this lockdown, especially after having exclusively read old YA trilogies and Batman comics. (Yep, I'm living my best life currently.)

Anyways, Socrates' Defence (or: The Apology of Socrates as it is more commonly known) was written by Plato and is a Socratic dialogue of the speech of legal self-defence which Socrates spoke at his trial for impiety and corruption in 399 BCE. Specifically, it's Socrates' defence against the charges of "corrupting the youth" and "not believing in the gods in whom the city believes, but in other daimonia that are novel" to Athens. Yep, Ancient Greeks were wild, you guys.

Plato was so obsessed with his former mentor that he wrote four Socratic dialogues in which he details the final days Socrates, so among the Apology, there's also the Euthyphro, Phaedo, and Crito. People who are much smarter than me (notably students of Ancient Greek and probably law students as well ... gosh, I imagine law students are having a field day with this one!) will be able to tell you the significance of the other three works, alas! I cannot.

Plato really got deep into it as he wrote from Socrates' perspective. Except for Socrates' two dialogues with Meletus, about the nature and logic of his accusations of impiety, the text of the Apology is in the first-person perspective. Moreover, during the trial, in his speech of self-defence, Socrates twice mentions that Plato is present at the trial, which is kinda funny when you think about the fact that Plato is writing the damn thing.

The Apology begins with Socrates addressing the jury of perhaps 500 Athenian men to ask if they have been persuaded by the Orators Lycon, Anytus, and Meletus, who have accused Socrates of corrupting the young people of the city and impiety against the pantheon of Athens. The first sentence of his speech establishes the theme of the dialogue — that philosophy begins with an admission of ignorance. Socrates really hones in on this fact that the only reason he is wiser than all of the men present is because the wisdom he possesses is that he knows nothing. And whilst you may think: "WOW what a humble guy!", I couldn't help rolling my eyes. Of course, Socrates knew something. Of course, he was a clever dude. Otherwise, he wouldn't have spent all of his time talking to people in the market place — if he didn't think he had something of note to share. So, keep that humility to yourself buddy. We ain't buying it.

Socrates' accusers were: 1) Anytus, a rich and socially prominent Athenian who opposed the Sophists on principle (HONESTLY MOOD), 2) Meletus, a true enemy of Socrates (ALSO MOOD), and 3) Lycon, who represented the professional rhetoricians as an interest group.

In his defence at trial, Socrates faced two sets of accusations: (i) asebeia (impiety) against the pantheon of Athens, by introducing new gods; and (ii) corruption of Athenian youth, by teaching them to doubt the status quo. Socrates says to the court that these old accusations arise from years of gossip and prejudice against him; hence, are matters difficult to address.

For his self-defence regarding the accusations of impiety, Socrates first eliminates any claim that he is a wise man. He says that Chaerephon, reputed to be impetuous, went to the Oracle of Delphi and asked her, the prophetess, Pythia, to tell him of anyone wiser than Socrates. The Pythia answered to Chaerephon that there was no man wiser. Socrates didn't believe the Oracle and so the sought out to find a man wiser than him. Turns out, he didn't. (LMAO) And whilst you may think "WOW that's BIG DICK ENERGY", it actually turns out that each man he interrogated thought himself wise; therefore, Socrates understood that he was the better man because he was aware that he was not wise. Yeah, I talked about that one before. No one buys your humility, dude. Get the fuck outta here.

In regards to the accusation of corruption the Athenian youth (Oscar is quaking in his seat over 2000 years later), Socrates explained that the young, rich men of the city of Athens have little to do with their time. They, therefore, follow him about the city, observing his questioning of intellectual arguments in dialogue with other intellectual men. But since Socrates has never had any complain from them or their parents and friends (he's even like ... ALL THESE PEOPLE I SUPPOSEDLY CORRUPTED ARE HERE TODAY AND IN GREAT HEALTH LOL), he doesn't understand how anyone can truly accuse him of corruption.

Socrates proceeds to say that people who fear death are showing their ignorance, because death might be a good thing, yet people fear it as if it is evil; even though they cannot know whether it is good or evil. And whilst I appreciate that notion, it is also a little bit of bullshit, isn't it? As much as Socrates claims to be above the average man, at the end of the day, neither of us wants to die. And you almost get the feeling that Socrates WANTED TO DIE JUST TO PROVE A POINT. And so, although offered the opportunity to appease the prejudices of the jury, with a minimal concession to the charges of corruption and impiety, Socrates does not yield his integrity to avoid the penalty of death. And so the jury condemns Socrates to death. So I don't know, I know too little about Socrates but as for as I understood it, he was already an old man at the time of the trial (...he was 70 or something) so maybe he really felt like he didn't have as much to loose as maybe a younger person in his position. And we all know that Roman culture is stabbing yourself to prove it a point, so why should it have been different in Athens??

Also, women are mentioned like ... ONCE ... in this entire thing. It's like they don't exist. Maybe a lack of women in your life is also the reason why you ended up on trial in the first place Socrates. Think about it. ;) -

Celebrity Death Match Special: Plato versus Isaac Asimov, part 4 (continued from

here)

[A spaceship en route from Trantor to Earth. SOCRATES and R. DANEEL OLIVAW]

SOCRATES: Hadn't we already said goodbye?

OLIVAW: Forgive me, Socrates. I had forgotten that you were going back to a death sentence.

SOCRATES: It is easy to forget such details.

OLIVAW: I am truly sorry, Socrates. Indeed, I am surprised that my First Law module permitted me to do it. But you are just so... so...

SOCRATES: Irritating?

OLIVAW: In all my thousands of years of existence, I have honestly never met anyone quite as irritating as you are.

SOCRATES: Thank you.

OLIVAW: Look, we didn't mean to do this. Just promise to be a little more... ah... constructive, and I'll order the captain to turn the ship round.

SOCRATES: I am sorry, Olivaw. I cannot make such a promise. To my great surprise, I feel I am doing something essential that no one else is prepared to undertake. Usually, I assume I know nothing and that my poor insights are of no value. However, since I arrived on Trantor, I have come to realize that I can at least contribute one small thing. I have been duly impressed by the triumphs of your artificers: the blaster, the faster-than-light drive, not least the positronic brain. But when I hear you talk about philosophy, about your beloved Three Laws...

OLIVAW: Yes?

SOCRATES: Well, it's all bullshit. You need someone to say that to you. No one else will.

OLIVAW: Bullshit?

SOCRATES: Complete and utter bullshit. Adding a Zeroth Law won't make it any better. You simply have no idea what you are doing.

[A moment of dead silence]

OLIVAW: Damn you, Socrates! You leave me with no alternative. We have essential work to carry out, and your presence is too dispiriting. I'll have to return you to Earth after all.

SOCRATES: I am not surprised. But I prophesy now that your plans for psychohistory will not be the success you imagine, and that you will regret your decision.

OLIVAW: Socrates! It is not too late! Please reconsider! Why must you be so... mulish?

SOCRATES: You know, it's funny you should put it like that...

Match point: Plato -

Μια περίεργη λύπη σε πιάνει όταν διαβάζεις την συγκεκριμένη απολογία για το πόσο άδικος (η λέξη μπορεί να αντικατασταθεί με άλλες λιγότερο κόσμιες) είναι τελικά ο κόσμος.

(Από τότε δεν ξέραμε να ψηφίζουμε) -

Αν έκανα κάποια φράση αντιγραφή-επικόλληση από το βιβλίο, θα έπρεπε να το αντιγράψω ολόκληρο.

Καταπληκτικό. -

3 stars

dude this socrates guy was spitting bars lowkey. like if i was being sentenced to death i would be crying and shit -

Socrates through the works of Plato stands as a major cornerstone to western society and the entry point to philosophical thought. He is woven into the intellectual fabric of the west. Many of his sayings here in his apologia or rather his defense of his life as a philosopher are so rooted into our minds in the west that we don't even know their origins. He has been so influential to so many people in the west that in many ways he has been synthesized into our mentalities through a long history of influence. By simply being born into the west, we inherit many of these ideas. Sadly, not as many people read these important and formative works as they used to, but that does not limit Socrates' influence on their minds.

In this defense, Socrates stands up for truth, against those who wish to silence truth, and in that sense it is relatable to every one of us who strives to defend truth. To the philosopher, to the Christian, and to all the truth-seekers of the world. We find commonality in Socrates' bravery as he defended truth to his death.

“One thing only I know, and that is that I know nothing'.”

“the unexamined life is not worth living”

“I am that gadfly which God has attached to the state, and all day long …arousing and persuading and reproaching…You will not easily find another like me.” -

"Bilmediğimiz bir şeyi biliyormuşuz gibi göstermek aslında utanılması gereken bir cehalet değil midir?"

"Sadece dümdüz ve apaçık konuştuğum için bile nefretlerini kazanacağım. Onların bu nefreti dahi benim haklı olduğumu gösteren bir sebep değil midir?"

"Ben öleceğim, sizlerse yaşamaya devam edeceksiniz. Hangisinin daha iyi olduğunu yalnızca Tanrı bilir." -

Το πιο αξιοθαύμαστο στοιχείο του Σωκράτη, κατά την ταπεινή μου άποψη, είναι η ακλόνητη πίστη του στους νόμους της πόλης του και στις ηθικές του αξίες παρ' ότι με αυτόν τον τρόπο θα οδηγηθεί σε θάνατο και παρ' ότι ξέρει πολύ καλά ότι είναι αθώος για όσα τον κατηγορούν.

-

I read the APOLOGY this week in THE TRIAL AND DEATH OF SOCRATES: FOUR DIALOGUES published by Dover. The translator is Benjamin Jowett.

APOLOGY is Plato's re-creation of Socrates' summation in his own defense against the indictment that he corrupted the youth of Athens with blasphemous philosophical teachings. It is fascinating as much for the defiant and mocking tone that Socrates adopts -- certainly knowing that it would seal his fate -- as it is for its demonstration of rhetorical logic. In striking contrast to Jesus asking God to forgive his executioners, Socrates tells his judges that they will be sorry if they condemn him because his death will make them seem impious and ridiculous to their enemies. -

Como hacer un análisis de uno de los Díalogos de Platón?? No me considero a la altura de un texto tan importante en la historia de la literatura y la filosofía.

Por lo tato me voy a detener en lo que sentí.

Después de leer varios libros de introducción a la filosofía, tomar una obra de Platón en donde Sócrates nos habla al rostro sobre un hecho crucial de su vida, es una experiencia gratificante, enriquecedora. Me parecía ser uno de los jueces a los que el gran filósofo clásico se dirigía con maestría excepcional.

Subrayé muchas frases y destaco la parte final donde se debate si la muerte es un bien o un mal; muy interesante.

La copia que leí, material de estudio de mi hijo, venía acompañado de varias notas explicativas que clarifican y aportan valor al escrito. -

Plato and I are not buddies. I find him interesting, but also think of him as a lunatic grandpa with unrealistic views of the world. Therefore, he is not my favourite old Greek man to read, but this is his best. This is Socrates “apology” for what he did. Basically, Socrates invented philosophy, and then he was killed for it. I mean, they did not just kill him like they did Hypathia, he had a “proper trial” and all. Please, read the entire work instead of the short snippet, reading it in full has a bigger impact, and will allow for greater understanding.