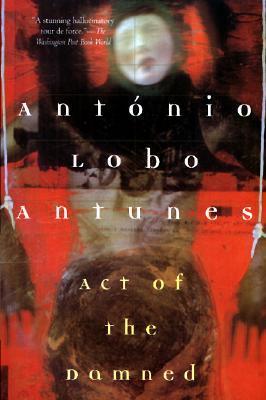

| Title | : | Act of the Damned |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0802134769 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780802134769 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 246 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1985 |

| Awards | : | Grande Prémio de Romance e Novela APE/IPLB (1985) |

Act of the Damned Reviews

-

Southern gothic comes to Portugal. As I wrote of Antunes' work in another review,

An Explanation of the Birds, every character is deeply flawed; every cup is cracked; every window is grimy; every spoon is greasy. The story is set in the 1970’s around the time of the Portuguese revolution when the dictator Salazar was overthrown and a socialist government was installed. An old established family finds itself on the wrong side of the political wind. As the patriarch lays dying, the children desperately search for his will hoping to get money to flee the country. But they are bankrupt -- financially, morally and spiritually.

Two of the patriarch’s children are mentally challenged – his 60-year old son is always underfoot playing with trains; his sister calls him “monkey brother.” But the diabolical immorality prize goes to his son-in-law who has fathered an illegitimate retarded daughter and a grandchild by her as well. He is the main character, a dentist who is disgusted by his clients. He works on teeth with a television on showing old classic American movies: Edward G. Robinson, Gene Kelly, Leslie Caron

The old patriarchal family lives in decrepit elegance. (This could be a genre – old families hanging on to their crumbling, decaying mansions in what has become the wrong side of town – I think of Sabato’s On Heroes and Tombs in Buenos Aires and Hatoum’s A Tale of a Certain Orient set in Manaus, Brazil.) Tarnished silver, moldy books, leaky roofs, dogs crapping on rotting carpets, tattered brocade.

It’s an ugly story with strong literary writing. Here are some examples of Antunes style all within two pages:

“…the smugglers I sometimes saw in the tavern, leaning over the bar to talk business with the bar owner, their mouths full of cheese and good deals.”

“…the empty pantry, occupied by a solitary old woman in a wheelchair, her bugging irises gleaming with affliction.”

“…the rain changed the color of the sounds I was hearing, turning them thick and dark, heavy like tears, and I smelled a profound dustiness, as if from a trapdoor that had been shut for centuries.”

Chapters are in voices of the different characters. The tension builds as the family tries to get itself together to flee the country. An ugly story but a fascinating read.

(Photo from thecitypictures.net) -

“E pensei Que falta o ódio faz para nos sentirmos saudáveis, e pensei Acharmo-nos em harmonia com o mundo é uma infecção mortal.”

Depois dos psiquiatras das obras que li anteriormente, Lobo Antunes traz-nos um dentista fascinado pela era dourada de Hollywood, que age como se fosse o Edward G. Robinson e dá o tom para todo o livro, pois é realmente como se nos tivessem administrado uma dose de gás hilariante. Depressa saímos de Lisboa e chegamos ao Alentejo onde uma família em plena decadência financeira e moral espera que o hediondo patriarca morra para tratar das partilhas e fugir para Espanha, com receio dos comunistas do pós-25 de Abril. As personagens e as situações são dignas de um dos melhores filmes de Almodóvar, mas a escrita é a mais perfeita renda de bilros.

Na verdade, diria que é mais que o Auto dos Danados: é o auto dos depravados, dos degenerados, dos desprezados, dos desesperados, dos perfeitos anormais. Uma obra-prima.

“Mas não há nada que os espelhos não destruam ao reenviarem-nos a nós mesmos, manchados de carimbos de estanho como encomendas postais sem endereço, de forma que me levantei, peguei no relógio dos anjinhos pela base e assassinei todos aqueles sardónicos rectângulos de vidro nas suas grossas molduras de talha. (...) Foi a minha mãe que quis o quarto assim, foi ela que o enfeitou desta maneira a seguir à morte do meu pai a fim de se sentir, ao menos, acompanhada por si própria, ou nem sequer por si própria mas pelas suas onduladas e mentirosas miragens, sabendo perfeitamente que o que vemos de nós é tão diferente de nós como o somos de um estranho." -

When I scan this novel—which is not the case with all the books by this author—I am talking about technical ease and interest that does not get lost. I loved and admired him. I enjoyed finding him whenever I could. For these reasons, I recommend it without hesitation to see how Lobo Antunes is a great writer.

-

”Auto do Danados” o sexto romance do escritor português António Lobo Antunes (n. 1942) foi publicado em 1985 e a narrativa começa ”Na segunda quarta-feira de Setembro de mil novecentos e setenta e cinco (…)”.

Com a Revolução do 25 de Abril de 1974 ou a Revolução dos Cravos ocorreu a deposição do regime fascista/ditatorial, o denominado Estado Novo ou salazarista, em referência a António Oliveira Salazar, o seu fundador e inicial líder; num movimento revolucionário iniciado por vários sectores militares das Forças Armadas que destituíram o governo liderado por Marcelo Caetano. Como resultado, todos os partidos políticos foram legalizados, assistindo-se, igualmente, à extinção da polícia política PIDE, entrando o país numa indescritível agitação revolucionária.

Até que por vicissitudes várias inicia-se em 1975 um dos períodos revolucionários mais conturbados – o denominado Verão Quente de 1975 em que o governo passou a ser dominado por uma esquerda radical liderada pelos militares Costa Gomes, Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho e Vasco Gonçalves, com a estatização de sectores industriais e bancos, e pela ocupação de terras para implementar a reforma agrária.

Para Nuno, o primeiro narrador, dentista, a ”(…) segunda quarta-feira de Setembro de mil novecentos e setenta e cinco (…)” é o seu último dia de trabalho no consultório antes de fugir com a sua família para Espanha, receosos do radicalismo revolucionário que se está a instalar em Portugal.

O enquadramento social do primeiro narrador, Nuno, e da sua família é evidente; pertencem a uma família burguesa, vivem no Restelo, o bairro mais elitista da capital portuguesa, Lisboa, num quotidiano dominado pela mentira e pelo desrespeito – ele traí a sua mulher Ana com Mafalda – e que é confrontado com a situação terminal de Diogo, o patriarca da família, no leito de morte na sua mansão, na herdade situada nas proximidades de Reguengos de Monsaraz, Alentejo, e do rio Guadiana, onde os seus filhos e demais familiares se confrontam com o fim do “pai”, “aparentemente” o pai extremoso e genuinamente puro e exemplar, mas que na realidade é o latifundiário temido e autoritário, violento para os familiares e para os trabalhadores rurais, exercendo arbitrariamente a violência e o ódio, num cenário dominado pelas traições conjugais, pelas ligações familiares ilegítimas, numa violência desmesurada.

O romance ”Auto dos Danados” vai sendo construído e desenvolvido com recurso às memórias dos vários narradores, em cinco capítulos: “antevéspera do festa”, “véspera da festa”, “primeiro dia da festa”, “segundo dia da festa” e “terceiro dia da festa” - em vários períodos e espaços que se vão cruzando, no presente, no passado mais recente e no passado mais longínquo, numa interpretação e numa perspectiva individual, pensamentos por vezes desordenados e complexos de acompanhar, pela multiplicidade dos relatos dos membros familiares, num enredo fragmentado e com critérios diferenciados pelos respectivos narradores, sobre as complexas relações familiares, entre homens e mulheres, sobre os distúrbios mentais e a esquizofrenia; uma das personagens é portadora de síndrome de Down, a “mongolóide”, sem nome, e muito mais.

António Lobo Antunes desmistifica de uma forma exemplar a normal percepção de harmonia no seio das famílias burguesas, supostamente abastadas, num tom quase sempre sarcástico, violento e misógino, sobre a desagregação familiar, espiritualmente e financeiramente, num dos períodos mais conturbados da recente história de Portugal, numa analogia perfeita entre a família e o pais.

”Auto do Danados” é um excelente romance, indispensável, mas de leitura exigente e proactiva.

António Lobo Antunes - 86º Feira do Livro - Lisboa - Portugal (2016-05-28)

António Lobo Antunes, o eterno candidato ao Prémio Nobel da Literatura, proferiu as seguintes declarações sobre a entrega do prémio a Bob Dylan em 2016:

Como é que está?

A trabalhar. O que é que hei-de fazer? Não tenho mais nada para fazer...

Também estou a trabalhar. Não tenho mais nada para fazer...

(risos) Pois. Não temos mais nada para fazer, olhe.

Queria ter uma reacção sua à atribuição do Nobel ao Bob Dylan.

Não vou dizer nada. Nunca falei quando me deram prémios, não vou falar quando não me dão.

Estava a referir-me ao Bob Dylan em si.

Eu gosto.

Porquê?

Gosto das letras, gosto das músicas, acho que é muito bom.

Não fazia ideia.

Não gosta dele?

Não conheço bem.

Vale a pena ouvir. Ele é bom. E é um homem interessante.

Recorda-se de alguma música em particular?

Tem várias. (silêncio) Isso é uma coisa, outra é darem um Nobel a uma pessoa que faz canções. Mas isso não tenho nada que ter opiniões.

Sabe que está toda a gente a estranhar o prémio.

Há muita indignação, é?

É. Porque é um cantor.

Não me quero meter nisso. Normalmente não faço comentários quando dão o prémio a alguém. É muito fácil dar opiniões. Mas isso de que serve? A gente pode questionar as coisas a outro nível, mas isso não me interessa. Para mim o Prémio Nobel da Literatura não é aquilo, mas é uma opinião pessoal, posso não ter razão nenhuma. As pessoas fazem o que quiserem.

É o que as pessoas acham. Começando pelo facto de o prémio ter sido dado a um cantor.

Isso é discutível. É evidente que há grandes escritores que nunca ganharam nada. O Tolstói, tantos. Todos os prémios são aleatórios, todos os prémios são discutíveis. Dêem a quem derem, as pessoas discutem. Eu não daria, mas isso é uma opinião pessoal, não quero polémicas nem chatices nem nada. Deram àquele, pronto, não tenho que discutir. Quem sou eu para dar opiniões?

In revista Visão (13 Outubro 2016) -

"What the hell is this?" Is undoubtedly the spontaneous exclamation of the reader after some 20 pages into this novel. Because at first you seem to have ended up in a fairly conventional story, where the narrator informs you that everything is happening shortly after the Carnation Revolution in Portugal (1974), in a wealthy family that feels threatened by the omnipresent communists and wants to flee to Spain, and against the background of the patriarch of the family who is dying.

Those information elements are useful, there is no doubt about that, because you regularly see references to that frame story pass by. But Lobo Antunes deliberately drowns them in a whirling multitude of voices and perspectives, some of which are recognizable, others not (or not at first sight), and in which time layers, real and imagined reality flow through each other, in a bombastic ensemble of clattering sentences that sometimes don’t seem to go anywhere. Occasionally there are passages that charm by their intimacy or their hilarity, but they alternate with gross, brutal, and absolutely degenerate situations; it is no coincidence that the words 'imbeciles', 'mongols' and 'incest' regularly fall. The cacophonic style seems to be deliberately meant to evoke the chaos of a family that feels the ground under its feet moving away. Or does Lobo Antunes just wants to indicate that life itself is so coarse, degenerate and enigmatic?

The least you can say is that this novel intrigues and that the author has a lot to offer. The references to Faulkner and Marquez certainly are not unjustified. But I cannot say that I really enjoyed the burlesque atrabilious-ness of this book, for me it was really over the edge. Perhaps this was not the best choice to get to acquainted with Lobo Antunes, or was it? -

Um dos romances que mais retrata a sociedade portuguesa do século XX. É a história de uma família na época Salazarista.

Representa um Portugal pobre, desfalecido, sem glória e alegria. Uma sociedade em que as mulheres são dominadas através de chibatadas e pancadaria. -

“Act of the Damned” is an absolute lunatic novel. The disturbingly besotted and predatory air of Antunes’s work is reminiscent of dark and frenetic passages from Hunter S. Thompson, Ignacio de Loyola Brandao, Boris Vian and perhaps the creepiest bits of Roald Dahl. This is to say that the prose is unusually visceral, coarse, disorganized, playful and interested in avoiding pretention in favor of a swaggering strangeness.

A few scattered sentences like, “After endless nights of talk and drink and syringes, of God knows how many grams of pills and heroin, I return to the world at two or three in the afternoon, surrounded by your collection of old hats, the overflowing ashtrays and the smell of urine from the Siamese that struts over the covers while we sleep, I return with the weariness of a septuagenarian frog, my kidneys splitting with pain as I flounder in a swamp of algae” made me feel like I could imagine what sort of influences went into the scattershot construction of this multi-generational festival of avarice, decay and retardation.

The novel is challenging, not least of all because there are at least nine different narrators (members of the family, the family’s doctor, a hapless notary), many of them unannounced and few of them in absolute control of their chapters. A reader suddenly realizes, based on rare instances of direct address in imbedded dialogue, that someone new inhabits the first person perspective, around whose discomfort and frustration Antunes layers his ubiquitous, over-the-top prose. (He could be faulted for failing to differentiate these narrative voices more clearly.).

For long stretches, Antunes will also narrate several things at once, overlaying them in alternating sentences. Sometimes it is clear that he is doing this to show how the surroundings (usually noise, heat and squalor) are so oppressive and irritating that they literally intrude upon the happenings and at other times, it seems to a bit more haphazard and “cut up.” For instance, “ ‘Wackawackawacka,’ said my cousin in Turkish to the Saint Bernard, who immediately withdrew his submissive finger. The mongoloid finished her oatmeal in a typhoon of soggy morsels, and the maid used the torn shirt to wipe her clean before unstrapping her. The procession trampled over the already twisted, tortured lanes to the accompaniment of clarinets, trombones, and tambourines in a heart-rending display of miserable splendour. The fireworks burst into luminous flakes in the air and we only heard them once they were fading in powdery threads. ‘What are you nosing around her for?’ asked my aunt, her eyelids heavy with rage. ‘We got you that cabin and bought you the looms on the condition that you never again set foot in this house.’”

Antunes is also quite comfortable, cobbling together virtuosic sentences that, with the addition of the retards, had me thinking of a more substance-addled, more embittered and less fussy William Faulkner, “My shotgun was tucked under my armpit and my cartridge belt held four or five dangling birds that had interrupted their flight (the hounds fetched their riddled corpses) to fan my haunches, and I arrived at the bedroom door trailing dust from my boots on the carpet and smelling of gunpowder, the earth, the woods and the blood of rabbits and turtle-doves, and my wife, who didn’t look at me, was pulling dresses from the closets and laying them on the bedspread, folding blouses, gathering up her underwear and shoes, and tugging on the leather straps of the open suitcases, knowing I was watching her—my gun in hand and my navel crowned with partridges, looking like a holy card of Our Lady surrounded by murdered angels—watching her move forward and backwards and sideways in the mirrors, as if it were twelve instead of one that I’d married, until I asked, ‘What the hell’s going on?’”

I’m letting Antunes’ prose speak for itself. While it fits into the cluster of authors I mentioned at first, it is unique and will either repel a reader within five pages or make him tolerate heaps of cruelty, mockery of retards, incest, random violence, scheming and confusions. As I read the novel, I was, at times, unsure what I thought of it and unsure of whether or not I would read Antunes again. In retrospect, I may just have been too overwhelmed and off-track to enjoy it properly. Skimming it again and reviewing the passages that I marked, made me certain that I will tackle another of this man’s books. -

I really disliked this book. I like to read authors from the countries I visit and Atunes is my first Portuguese one. The praise on the book cover led me to believe that this was going to be a passionate family story, but I found every character to be disreputable. There was no moral center so I felt disconnected and didn't care about any of the characters. There wasn't anyone I could slightly root for. Even anti-heroes in books or movies the audience roots for, with a sense of guilt.

I don't like a lot of metaphors and similes in the books I read because I often find them illogical and interrupting to the flow of a narrative. Writing can be beautiful and deep without constant comparisons. This book is full of similes and they rarely had the effect intended. Most of them didn't make sense or mixed metaphors. Here is an example of a really bad simile,

"My sister turned on the spigot, which resembled a gaping fish-mouth, and I reached for a tentacle of soap, stretched out like a fakir on a bed of rubber nails. Bending over the the running water without touching it, I stared in amazement at the fish's continual, turbulent, imperturbable vomit" (134).

It starts out all right but then switches comparisons mid sentence, moving from an aquatic comparison to a religious one, not to mention it ends disgustingly.

The other major problem I had is the book has many narrators, mostly members of the family, the notary being an exception. Multiple narrators is common so I don't have a problem with that. My problem is with the voice and tone of the book. The characters had their own personalities, flaws and troubles, but from the narration itself they all sound the same. Everyone thinks in the same heavy metaphorical way and there is very little to differentiate from the style of the writing who is the speaker. I think if an author is using more than one narrator then the writing should reflect the different personalities and thought-processes of each narrator. Any differences were very subtle. Even when Francisco, the youngest of the narrators, talks he sounds the same. And the first narrator seems to have an inordinately long section even though he is not in the rest of the book, and is just an in-law (although the other in-law does play an important part). This first character, Nuno, is just as fucked up as the rest of the characters and may have committed two murders for no reason, if they even happened and weren't just his overworked imagination.

What kept me reading was the novel is short so it felt like I should finish it. The prose does have a certain rhythm to it that moves the reader continually onward and I can see how people would find it beautiful, especially if they like the heavy-handed metaphors. Toward the end of the book the theme of the paranoia about encroaching Communists and the need to flee to Spain with some semblance of financial well-being becomes prominent, almost making the novel worth it.

Maybe it is a translation issue, or maybe it is that my experience with Portuguese people had nothing in common with these immoral "white trash" characters who didn't care about anyone, not really even caring for themselves. But of course, 2015 is a very different cultural period for Portugal than the 1970s were. -

This irreverent and almost indescribably wacky novel is initially set in September 1975 in the Portuguese capital of Lisbon, less than 18 months after the Carnation Revolution spelled the end of the fascist Estado Novo, the beginning of a democratic government, and the end of colonial rule and civil wars in Angola, Mozambique and elsewhere, as wealthy conservative families saw their worth plummet. The motley cast of characters consist of the younger relatives and in laws of a dying wealthy patriarch who lives in the Alentejo, as they seek to claim his substantial inheritance before they flee to Spain, which was still under the dictatorial rule of Francisco Franco. The novel consists of narratives from different family members, and from them the decadence and depravity of each of them is revealed, with frequent references to infidelity, incest and other immoral behaviors. The characters are absurdly funny but neither believable nor worthy of sympathy, and because I could not relate to any of them I struggled my way through this novel, even though I'm a fan of Antunes's work.

-

Em 'O Som e a Fúria', William Faulkner percorre a decadência de uma família do sul dos Estados Unidos, através do ponto de vista de cada uma das personagens. Começando pelo marido da neta do patriarca moribundo, passando pela filha, nora, netos e pelo genro, Faulkner revela o estado financeiro e social de uma família habituada a viver à custa de quem trabalha, ao ser confrontada com uma herança de dívidas e o comunismo a bater à porta.

Semelhanças à parte, António Lobo Antunes cria uma imagem vivida duma época não tão distante dos nossos dias, que faz parte do imaginário popular português como um conjunto de roubos legalizados ou como uma romântica justiça por séculos de servidão. Num cenário idílico, rumo de milhares de turistas todos os anos nos dias de hoje, um povo alheio à maior parte das convulsões políticas que estariam a decorrer na cabeça dos caciques, festeja a morte do touro na arena. -

It wasn’t an easy read, both because of Antunes’ complicated but impressive literary style, which was a first for me, and because I read it in English. It was an introduction to a Faulknerlike, to be followed by Faulkner himself. This is the story of a horrible (or horrific) family and its members none of which are to be liked. There’s violence, incest, sickness (physical, emotional and ethical) all over the place. Though I detested the characters, the family, the core of the story, I was in awe of how it was portrayed back and forth through time, with reality versus fantasy.

This was recommended to me by the staff of Livrario Lello in Porto, Portugal for a contemporary but not so internationally known Portugese writer while travelling there, so bravo to them, too.

I hope it’s translated into Turkish one day so I can read it in my native language again. -

“[…] Portugal […] não existia. Era uma ficção burlesca dos professores de Geografia e de História, que criaram rio e serras e cidades governadas por sucessivas dinastias de valetes de cartas, a que se sucederam, após meia dúzia de estampidos chochos de barraca de tiro, sujeitos de barbicha e lunetas aprisionados em retratos ovais, observando o Futuro na miopia severa dos eleitos, para tudo se diluir na paz branca sem relevo nem contornos do salazarismo […]”

“[…] todos se consideravam com direito a nada num país onde nada é o que geralmente se possuí e coisa nenhuma o que os defuntos nos deixam ao deixar-nos, além de dívidas e uma saudade zangada em relação ao lugar vago na mesa e ao riso do retrato, o qual vai perdendo substância com a agonia da memória.” -

Take some Faulkner or your favorite novel of Southern Decay™, move it to Portugal and add a generous dose of modern despicability. Then garnish with literary tricks. The book follows a wealthy family with a dying patriarch on the eve of cultural revolution. The characters, while all terrible, are decidedly memorable. The tricks, including changing perspectives and non-linear time are well crafted in that they shake things up without being a significant barrier. Particularly well done is how characters move into and out of fantasy or memory. The transitions are fluid yet discernible.

-

A book that wallows in the ugly with predictable incestuous entanglements and related grotesquery

-

As a Luso-American, I've been trying to read books by Portuguese writers other than Saramago. I want to learn more about the culture and the history. I want to hear Portuguese voices that are less well-known and more local in their interests. To be honest, Saramago has a little too much magical realism for me as well and I don't think he always addresses the elephant in the room which is the Salazar legacy.

This is the second Antunes book I've read and, god, what a bitter experience. He may not be as violent as Cormac McCarthy, but his world view is not much better. He writes at a level far above me with perspectives changing in mid-paragraph at one point.

I find his books compelling because of the characters. I have a dark view of the world too and I like seeing characters that are more complex than the sanitized ones I watched on telenovelas growing up. I am also a Faulkner fan and I share Antunes' interest in decaying families..

Antunes is a also doctor and I can see that in his descriptions of bodily fluid, odors, and stuff I don't even want to mention. Sometimes, it was a little much.

I don't know if I'll keep reading him, but I appreciate his view of the Portuguese and their history. I will probably do so, particularly because he has novels about Angola and that is a topic I sorely want to know more about. -

A left-wing takeover of Portugal frames the events in this book, but aside from the opening and closing pages, the collapse of a family is the focus.

Thrown into this toxic political mix is a family that is morally, spiritually and intellectually bankrupt. The mansion seems to be falling apart around the dying patriarch. His insane children play at trains around his bedpan. And the only rational members of the family--who also happen to be the most morally bankrupt--circle to divide his fortune.

This is very experimental fiction that Antunes is providing here. Multiple perspectives come to play in the book, and the reader is never sure just who it is that's speaking. I often made it to the third or fourth page of a chapter before figuring out--oh, this is the character! And there were many places where the perspective shifted within chapter and within paragraph.

Another challenge the book provides is there are very few names used. The brother-in-law, the railroad engineer, the daughter. I think only four characters' names are used regularly, although others are provided indirectly through direct address.

This is a challenging read but also ultimately a good one. -

Nepoznanica koja me je oduševila. Toliko da opraštam čak i taj nepopravljivo gust i neodmjeren tekst. Stil je vrlo originalan, i usprkos ogromnom protoku, u svakom se slovu vidi majstorska ruka velikog romanopisca. Tragedija koja neodoljivo vuče na Faulknera u najboljoj formi, sa dozom južnog temperamenta. Ma genijalno.

-

Não foi nada do que previa. Não é apenas linguagem tratada e pura que faz um bom livro, é preciso consistência narrativa e coerência. Não existiu neste romance

-

É impossível ficar indiferente, à escrita e imaginação, do autor. Obrigado.

-

Num percebi um caralho! É capaz de ser culpa minha, que queria despachar isto rápido... Mas vai-se a ver e é culpa do autor, que me fez querer despachar isto rápido! Uma das duas deve de ser

-

acho que fiz uma boa descoberta com Auto dos Danados. Cada capítulo do livro é narrado por um personagem diferente, quase todos sem nome (ele fala de “o dentista”, “a mongoloide”, “a casada com o dos bondes”, “o engenheiro” etc) e sem qualquer introdução — você tem que pescar depois de iniciado o capítulo quem é mesmo que está falando. Conta de uma família portuguesa falida, que se reúne durante as festas do povoado porque o avô está moribundo. A partir desse reencontro, vai se desenrolando as misérias da família: um casamento falido, onde ambos os cônjuges sabem dos amantes um do outro; um tio que já dormiu com todas as mulheres da família — e do povoado —, incluindo sua cunhada débil mental (de quem tem uma filha, e com quem acaba também tendo uma filha); casamentos por interesse; o patriarca que forjou a morte da própria esposa porque esta o abandonara; a mãe que abandona os filhos e o marido e vai morar no Rio de Janeiro com um surfista e por aí vai.

O realismo e o exagero com que as misérias da família são narradas de forma crua e seca mostra como gerações e gerações podem se manter sem amor, sem cuidados e sem nada a se apegar, a não ser o dinheiro que eles esperam depois da morte do velho. Mas o que resta da fortuna que o velho mesmo dilapidou em anos de jogos, bebidas e mulheres acaba sendo gasto em tratamentos para os dois filhos com problemas mentais e no tratamento do próprio pai. Com a aproximação da Revolução dos Cravos, a família, afogada em dívidas e com medo dos comunistas, foge na mesma noite da morte do velho para a Espanha.

A cena da morte do patriarca é narrada em conjunto com a cena da morte do touro (está havendo uma tourada, que fecha os festejos que estão ocorrendo na vila) e, pra mim, é o ponto alto do romance, onde todos os personagens vão se mostrando profundamente aliviados com isso. Não há máscaras para cair, todos estão ali com suas misérias e usuras expostas, sem esconder nada de ninguém. O período narrado é de grande catarse pra todos, onde não têm nada a esconder nem jogos a jogar. É tudo exposto, de forma feita, na sua miséria psicológica e mesmo material, de gente vivendo em subúrbios fedorentos e no meio de relações de traição e descontentamento.

“Está morto, disse eu à família a compor a gola do pijama do velho, a arrecadar os instrumentos, a preparar-me para abandonar o quarto, descer as escadas, enfrentar os perdigueiros, tornar a Reguengos na ambulância do hospital. Está morto, disse eu, arrastem-no da arena pelos cabos que lhe seguram os cornos, amarrem-lhe as patas e levem-no e dividam-lhe a carne e vendam-na no talho, podem embebedar-se dois ou três dias com o dinheiro do finado, esse bicho enteiriçado e grosso, sem majestade alguma, que sangrava e que sangrava ainda.”

Li a versão que achei na Internet, mas estou muito interessada em comprar o livro físico pra ler de novo. -

I liked it and I will definitely get back to him as soon as I have a chance. The plot was completely uninteresting but actually that’s the magic of this book! How can it be so incredibly written and at the same time be so bland? Well… The plot is about this family that goes to visit a relative that is about to be dead and their expectations in this visit (getting money out of the old man, excluding people from the will through all kinds of tricks, etc) but the magic really resides on the testimonies from every character.

Lobo Antunes writes in such a way I have never seen before… He changes characters like nothing happened, you are reading a monologue written by one person and then all of a sudden you fell like the speech has changed and the opinions diverge and BAM it’s another character (which by the way, he never tells which, you have to figure it out by yourself!). At first you are extremely confused (it reminded me a bit of One Hundred Years of Solitude, but the confusion goes backwards), but has you start to recognize their way of expressing themselves it gets better.

Another very important fact, all this characters have a completely different type of dialogue and it seems like it wasn’t written by the same person… I’m having a hard time trying to express myself lol, but the truth is, he is an amazing author when it comes to technique and particularly versatile. -

Não sou de escrever sobre livros, mas este é excepção. É, talvez, o livro mais forte que li do Lobo Antunes. As temáticas são as conhecidas: virada de Portugal à esquerda frenética, ataque à aristocracia do antigo regime, famílias disfuncionais, crueldade do Ser Humano para com quem ama e o fosso que há entre o amor e a ambição do que realmente se quer. Um tratamento de linguagem como não há em Portugal. Sem espaço para a ética ou moralismos corriqueiros, mas com a vida lá dentro. Aqui, num sistema de estrelas só não atribuí 5, porque tive o infortúnio de o escolher como primeira obra do autor e daí não estar preparado para o embate. Quem o quiser começar a ler deverá agarrar na Memória de Elefante ou Os Cus de Judas e depois seguir para onde a curiosidade o levar.

Em jeito de conclusão, os que se sentem fatigados pela obsessão deste livro e dos outros do autor, absorvam com tempo. Livros escritos por mãos humanistas não são para ler de uma assentada. -

Finalmente um livro de António Lobo Antunes que não fala da guerra nem do trauma da guerra nem das consequências da guerra.

Este livro é sobre uma família, uma herança e um funeral. É um relato da miséria emocional de todas estas pessoas, das suas traições e dos horrores que vivem, viveram e viverão. Cada capítulo dá voz a uma personagem desta família, sendo que se sucedem coisas terríveis que nos permitem descobrir cada vez mais e melhor o que realmente se passou com este avô e com estes tios.

Apesar de as situações inferirem um certo nojo pela vida, e de o autor voltar a manifestar o seu ódio visceral por todos os animais (que não têm culpa nenhuma), temos uma narrativa muito bela, com recurso a processos estilísticos altamente sofisticados e que tornam a leitura rápida e vivaz.

Apesar de me ter demorado um pouco com este livro, foi uma leitura agradável e um dos mais satisfatórios ALA que li ultimamente. -

Zeker geen slecht boek, maar niet mijn smaak! Het is geschreven in een nogal chaotische en extreem bloemrijke stijl: dat is even leuk, maar na een poosje ben je het wel zat. Daarnaast is elk persoon in het boek of geestelijk niet in orde of gewoon afschuwelijk! Het speelt zich 1,5 jaar na de Anjerrevolutie in Portugal af, het moment waarop de communistische partij daar op zijn grootst was. De familie van de grootgrondbezitter is bang voor een eventuele communistische machtsovername en ik had zo'n hekel gekregen aan de personages in het boek, dat ik bijna ging hopen dat de communisten hen tegen de muur zouden gaan zetten (het is immers toch geen waargebeurd verhaal :-D).

Wie Marlene van Niekerks 'Triomf' waardeert, zal dit boek wellicht ook waarderen, maar ik ben dit soort personages snel zat en word er alleen maar sacherijnig van. -

This sophisticated account of a doomed assortment of people herded together as a family, told from various perspectives of some of the characters, is one of the most frenetic books I've ever read, strewn with cultural references and laden with symbolisms and absurd imageries, encapsulated in sentences like "...and the morning, pianoing the harsh notes of daylight on the windowsill, brought me back to the surface...".

It took a while for me to get adjusted with Antunes' style, what with his agile switching of time frame and point of view that reminds me of Vargas Llosa's works. A challenging read indeed, but hugely compelling, cynically funny and bleak. -

“Portugal, september 1975. Bijna anderhalf jaar na de Anjerrevolutie, wanneer de macht van de communisten op zijn hoogtepunt is, schaart een familie van grootgrondbezitters zich rond het sterfbed van een oude patriarch. Om de beurt vertellen ze het verhaal van hun aftakeling en ondergang. Als een reidans. Een dans der verdoemden.”

Dat zegt de achterflap.

Eerlijk? Ik vond het een vreselijk boek dat ik met bijzonder veel moeite doorspartelde.

Lees meer via

http://elidesc.com/2013/01/27/dans-de....