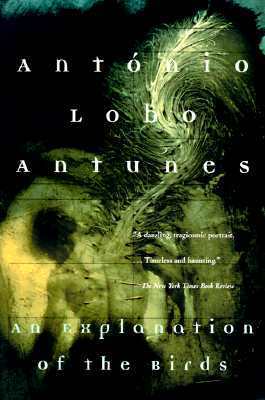

| Title | : | An Explanation of the Birds |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0802134203 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780802134202 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 261 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1981 |

An Explanation of the Birds Reviews

-

Another novel by the Portuguese author, António Lobo Antunes. (Bought at the 2017 Lisbon Book Fair.). Another novel that looks at the world of post-revolution Portugal. Another condemnation of modern life. Another cry for the individual. Part Bernhard. Part Beckett. Part Kafka. In this review I shall let the author do most of the work. He does it so much better than I.

Are we as we remember ourselves or as others remember us? And what does awareness of that disparity do to us? Who are we? Where do we fit in? Nowhere? This is a novel about a man, a history professor, about how he remembers himself and about how other people remember or, in some cases, do not remember him. It’s also about ‘An Explanation of the Birds’.

A young boy, Rui, and his father together at a family farm on vacation:

“... the farmhouse when I was little and my father sat me in his lap to tell me about the birds under the big chestnut tree ....”

“When I was little my father explained the birds to me, their nests, their habits, the way they fly."

“‘The birds,’ explained his father leaning against the well on the farm, ‘die very slowly, without knowing why and without even noticing, and one day they wake up with their mouths open, floating on their backs in the wind.’”

An important moment in the life of Rui - this is the childhood he remembers with his father. This is not what his father remembers. Neither his father, nor anyone else, has any recollection of the event at all.

“The birds,” his father murmured with an intrigued look, “what’s this with the birds?”

“Bird?” asked his confounded mother, “what’s this nonsense about birds?”

Have you ever been there? You describe an important moment, heartwarming or heartbreaking, from your childhood to your family. They look at you as though you’re an alien. No idea as to what you’re talking about. Part of your childhood has just been deleted, denied, destroyed. So much for family memories. And often your siblings take great energy from joining into the game. Taking apart your memories, at your identity. Picking at your life. Pick. Pick.

And that is, in many ways what the book is about. António Lobo Antunes, himself a psychiatrist by profession, presents us with a family taking one of its own to pieces. The father, the mother, the grandmother, the sisters, the ex-wife, the girlfriend,the brother-in-law, the sons, aunts - seemingly everyone that Rui has ever had in his life - even those who only had the briefest of contact with him. Now how is this the case? Why has Rui nobody who knows him? Whence the hostility to Rui’s self assessments?

I was reminded while reading this of the theories of schizophrenia and psychosis as put forward by R. D. Laing and David Graham Cooper in the ‘60s and ‘70s. The family or other social groupings are responsible for mental illness in individuals. Through contradiction and denial, families push the individual into a state of mind wherein they appear to be mad because they can no longer distinguish the world. The theories, an admixture of psychology and existential philosophy, were very popular in their day. We were all quite convinced that our families had made us psychotic. (Likely true) I even went to see Laing speak at one point.

But let us consider Rui for a moment. He lacks confidence. He is weak willed. He dresses badly. He was rejected by the Communist Party because of his bourgeois origins. (His father is a rich businessman is post-dictatorship Portugal. Prior to the 1974 ‘Carnation Revolution’ the father was a state minister.). But Rui is seen as a traitor to his family. Who Rui believes he is and who others tell him he is are contradictory.

“He'd taken her to his parents' for dinner, and through it all - during the cocktails, the meal, the conversation afterward in the living room, and the farewells in the foyer - he'd felt, on the one hand, their hostile etiquette, shocked by his girlfriend's poncho and clogs and extreme-leftist garb; and, on other hand, her proletarian rage as a national guardsman's daughter, stubbornly exaggerated in the coarseness of her manners and in her use of toothpicks.”

And so Rui drives his girlfriend, Marilia, to a seaside hotel in the small town of Aveiro because he intends to break up with her. He can no longer make sense of their relationship. She asks why he wants to go to Aveiro.

“You want to know why Aveiro?” he asked Marilia. “There are dozens of sea gulls around the inn, among the rushes, on the muddy banks, in the lagoon itself, and on the anchored barges."

But Marilia ups him one and breaks up with him first. Then she takes a cab back to Lisbon leaving Rui with his teeming mind and the ever present birds. He walks around the lagoon, through the marsh, always surrounded by birds. As he walks his mind slowly let’s go. He no longer is a person in himself. Instead, his mind takes him to a circus, a circus made up entirely of those people who matter to him: his ex-wife, his ex-girlfriend, each of his sisters, his children, his father, his mother, his brother-in-law. Each performer gives her opinion of who Rui is, of what is wrong with Rui. And each contradicts the others. Rui spins around and around the circus ring and becomes another performer. (The ringmaster?)

"Ladies and gentlemen, girls and boys, distinguished guests whose presence and enthusiasm honor us here tonight," cried the dwarf while signaling with a raised sleeve for Ravel's Bolero to stop. "We have the privilege of presenting to you The Wives. round of applause for The Wives, if you please. The orchestra drum let loose with a lugubrious roll and a spotlight switched on, illuminating the ceiling of the circus tent star could be seen through a rip in the canvas), a gently swinging trapeze bar, and, standing on the bar in slippers and sequined bathing suits, Marilia and Tucha, who waved to the audience as chalk dust fell from their palms.”

“‘He never went with me to the supermarket,’ stated Tucha, hanging from the bar of the trapeze by her knees while Marilia, hands joined to Tucha's, swung in the emptiness. ‘And when I say supermarket that also means the butcher, the baker, the tailor, the toy store, and so on. I was the one who took the car in to get the oil changed.”

"He thought that everyone existed as a function of him," Marilia affirmed, flipping over herself in a complex maneuver that the orchestra emphasized by speeding up the rhythm . . . .”

“ . . . we have honor of announcing that the remarkable Rui S. will proceed, in just a few short moments to the historic consummation of his courageous act. For the first time in Portugal, in a strictly untelevised performance brought to you by our gracious sponsors, a performer will sacrifice himself before your eyes, thereby providing you with a few moments of pleasant distraction from your daily concerns, headaches, and anxieties.”

“Cut this one s tummy,” my father in structed, pointing with his finger. "Cut this one's tummy so that I can explain it to you." He still opened his eyes, still tried, with all his might, to get up from the sand, to rise in the saturated air and join himself to the sea gulls that circled around his supine body, but the knife, the needle, the knife pinned him down to his sheet of paper, and as his eyes began emptying and his ears stopped hearing the audience's wild clapping, he was able to make out, beyond the resplendent circus lights . . . .”

And the inquest into Rui’s suicide, where the hotel receptionist testifies.

“The deponent wished furthermore to call attention to the frantic commotion of the sea gulls, mallards, and other smaller birds whose names, common or scientific, are unknown to her; said creatures all demonstrated an absolutely singular behavior, such as she had never seen - to wit, on the one hand protecting the cadaver and on the other hand tearing it to pieces, reducing it to confused shreds of blood and clothing, greatly hindering the removal of the body, thereby an operation made all the more difficult by the birds’ fury, which was unleashed against anyone who tried to approach the corpse, so that ultimately it took shotguns and fire-truck hoses to disperse them.”

Picking Rui to pieces. António Lobo Antunes has portrayed a modern man who does not stand a chance even in death he is picked to pieces. Pick. Pick. Pick.

A highly recommended novel. -

Revised, pictures added 5/16/22

Every character is deeply flawed; every cup is cracked; every window is grimy; every spoon is greasy. The seaside resort is choked with fog and seaweed. When you look out from the resort you see a homeless man defecating by the dumpster.

Welcome to Antunes’ Portugal. The story is set in the 1970s shortly after Portugal’s Carnation Revolution, when the dictator, Salazar, was overthrown.

Our main character is a teacher and a scholar who disappointed his father and his family by not going into the family business but into “the humanities” instead. That choice and his leftist leanings and leftist wife and later, girlfriend, shock his family’s conservative sentiments and seem to have been his downfall. The story is about that downfall and its tragic end.

The book’s title refers to one period in the man’s childhood when he actually adored his father and had conversations with him while on vacations at an old family farm. His father taught him about nature and “explained the birds to him.” All that is past; his father now is distant to him and doesn’t even remember those conversations that meant so much to his son. The father is only concerned with his mistress and is disconnected from his whole family.

The contemporary narrative of the novel is interspersed with mock interviews with members of his family, including his ex-wife and ex-girlfriend, looking back from much later in time, as if someone were writing a biography of the main character sometime in the future.

The narrative is also interspersed with circus commentary and freak show characters who keep up a running sarcastic commentary on the main character’s actions and motives. The main character is best characterized by his sister: “…of all the people I’ve ever met he was the least prepared for life.”

The protagonist comes to the resort to break up with his current girlfriend and she turns the tables on him leading up to the tragic ending. Like Antunes’ other works, such as Splendor of Portugal, which I have reviewed (the last thing you will find in that work is anything of splendor) there is a lot of psychological depth and local color of urban and rural Portugal. (In Splendor, the local color is of both Angola and Lisbon). But be forewarned, the local color is, like the windows, dulled by dirty gray sticky streaks.

With the passing of Jose Saramago, Antunes is my nominee for the next Portuguese Nobel prize winner. Born in 1942, he has written about three dozen novels, most translated into English. He is also a doctor and in the early 1970s worked in military hospitals in Angola.

Top photo of Pine Cliffs Resort in the Algarve from rentylresorts.com

The author from thedailybeast.com -

No es de lo que más me ha gustado de Antunes, pero siempre es interesante el aullido del lobo.

-

When the flesh becomes a word -

I wish you a pleasure identical to mine when I discovered Lobo Antunes. Here, we do not enter the text so quickly. We lose ourselves in time, the times of history, overlapping. We feel our mind follow in the author's footsteps, and we follow him in his metaphors of reality, never exhausted, always more poetic, sometimes funny, always correct, coming out of the guts! Cross the path of Antonio. He will not leave you indifferent. -

Il romanzo si suddivide in quattro parti, quattro giorni che sono come quattro ben distinti colpi di cannone. All'interno di ciascuno di essi, un esplosivo (proprio nel senso di distruttivo, nel senso che sbriciola tutto) flusso di coscienza che passa con nonchalance dalla terza alla prima e poi di nuovo alla terza persona anche nel giro di poche parole, raffiche di immagini e frasi come dentro un frullatore. Dopo un primissimo momento di disappunto mi sono ricordata di quanto mi fosse piaciuto "L'autunno del patriarca" di García Márquez, e allora vado avanti con maggiore entusiasmo.

Nella mente del trentenne protagonista, scrittore e professore, l'amarezza che egli sente nell'animo si mescola con lo squallore delle periferie e con la decadenza della famiglia e di tutto il parentado, per dare vita ad un immaginario circo che è anche parodia di un'aula di tribunale dove è lui stesso ad essere messo sotto accusa per il completo fallimento della sua vita. I tre livelli della narrazione - quello che accade nella realtà del presente, i ricordi del passato e il film con il circo che egli vede nella sua mente – sono così saldamente intrecciati e mescolati, eppure si seguono talmente bene che la cosa mi ha lasciato sorpresa. Tutto quello che Antunes vuole mettere in una pagina viene passato in una sorta di compattatore, oppure redistribuito secondo una nuova logistica delle parole, insomma il risultato è che nello stesso spazio disponibile a tutti gli altri scrittori, lui riesce a farci stare più roba. Di man in mano che si procede con la lettura, il circo dei vari testimoni si trasforma lentamente in una istruttoria vera e propria, e con molta eleganza il finale inizia a svelarsi: quello che nelle prime pagine si poteva vagamente supporre e presagire, a metà del volume è già una certezza e mancano solo gli ultimi dettagli sul come e quando.

Il titolo fa riferimento ad un semplice episodio, poco più di un'istantanea, relativo all'infanzia del protagonista: episodio che per lui è l'emblema autentico del paradiso perduto e del rimpianto. Queste immagini che nella sua mente vengono rievocate in continuazione, stridono fortemente e penosamente con le immagini del suo presente, dello squallore, della disillusione, del male di vivere (che si trasforma inevitabilmente in una serie di malesseri fisici: in questo senso, l'occhio clinico da parte di Antunes non manca di certo, e per quanto mi riguarda la lettura di questo libro si può considerare propedeutica a quella de "Il male oscuro" di Berto), del distacco con la famiglia che pure lui ama e dell'incomunicabilità con le due donne della sua vita che pure ha amato nonostante non sia mai stato ricambiato da loro (ma potrebbe anche essere il contrario, loro lo hanno amato mentre lui le ha solo detestate). Tutta l'infanzia e tutta la giovinezza gli sembrano come degli enormi e clamorosi errori, o forse è più corretto dire degli errori rimasti a metà, situazioni in cui non è riuscito a sbagliare abbastanza e fino in fondo per poi potere rinascere e ripartire. E da qui la sua perenne sensazione di non essere né carne né pesce. Mentre gli uccelli rappresentano sempre la libertà, la leggerezza, la via di fuga da questo mondo insopportabile, a volte sgraziati ma pur sempre con temperamento; tutti gli altri animali che compaiono – a volte animali nella parte di sé stessi, oppure figure umane momentaneamente animalizzate – sono invece sempre in accezione negativa, specialmente i cani: luridi cani randagi compaiono in ogni dove a rappresentare il degrado e l'abbandono di luoghi e persone.

A lungo andare questa esagerazione di contenuti in forma super-compattata inizia ad essere un poco ridondante, mi sono ritrovata con una vaga sensazione di iperventilazione. Quella certa aria di eleganza un po' sorniona che caratterizza i primi tre giorni (ovvero tre quarti) del libro, finisce inesorabilmente per svilirsi nel finale a causa di una ostinata ricerca dell'esplosione pirotecnica e un altrettanto ostinato tentativo di protrarre al massimo lo spasmo dell'attesa del gesto estremo: questa virata inattesa ha fatto sì che di un inizio di lettura a cui avrei voluto assegnare 5/5 mi rimanga un quattro stelle meno meno. La considero una lettura per me significativa ma non so se avrò voglia di provare altro di Antunes. -

Confesso que comecei com grande entusiasmo, sentindo uma intensa admiração por cada linha nos seus saltos temporais e nas mudanças inusitadas de narradores, surpreendendo-me com a originalidade de cada metáfora e a acutilância das descrições intensamente poéticas, mas a meio do livro comecei a sentir um certo cansaço, no final já só o queria fechar. Explicações?

Rui S. é assistente universitário, num Portugal recentemente saído de uma ditadura e da Revolução. Filho de famílias da elite, deseja abraçar o outro lado, o do povo. O que consegue é ser recusado por todos. Do pai e irmãs, à primeira mulher, da elite, e filhos, assim como a segunda mulher, revolucionária comunista, e seus camaradas. Rui sente-se um espécime, um pássaro a quem abrem a barriga para estudar, catalogar e depois arrecadar numa qualquer gaveta, como fazia o seu pai com a sua estranha coleção. Arrecadado e incapaz de escapar às imposições sociais, ou ausente de vontade e motivação para o fazer, entrega-se aos “pássaros”.

O enredo é profundamente dramático, e em vários momentos acompanhamos o protagonista sentindo a tragédia com ele, mas na maior parte do tempo somos brindados com sarcasmo e sátira moldados na forma de ataques, do autor, contra as elites assim como contra o suposto proletariado, o que retira força à leitura e interpretação do personagem, desgastando-nos. A nossa expectativa assenta no encontrar de uma explicação final, completa, capaz de dar conta de todo o sofrimento apresentada, mas ALA recusa-se a tal.

ALA dá conta do modo como as vidas humanas são feitas de relações e interações que não têm de ter explicações nem sustentações muito claras. Tudo é assim, mas tudo podia ser de outro modo, e tudo o que parece pode simplesmente não o ser. Cada instante é fruto de muitos instantes anteriores, mas mais importante, é fruto da interpretação e catalogação que lhe atribuímos que depende do contexto de cada um desses instantes. As descrições e amostras de cada personagem e eventos lançados no texto por ALA seguem o modo como pensamos e sintetizamos a realidade, os outros e tudo aquilo que representam para nós. Tendemos a construir o mundo como histórias — lógicas com princípio, meio e fim — mas aos poucos vamos percebendo que essas histórias, explicações do mundo, não passam de ilusões construídas por nós para nos podermos apresentar e facilitar aos outros a nossa catalogação.

O final do livro, com o modo Circo, é no fundo a grande explicação de ALA, que demonstra como somos atores e espetadores de primeira fila das nossas próprias vidas. Ainda que o cenário seja profundamente satírico, não fosse um circo. Contudo penso que esta foi a opção de ALA para não cair no melodrama, para não lançar mão da tragédia assente nas eternas questões existenciais. Ou então, porque simplesmente faz parte do modo como ALA prefere olhar o mundo, não aceitando a excessiva seriedade com que tendemos a filosofar sobre aquilo que somos.

Publicado no VI:

https://virtual-illusion.blogspot.com... -

Antunes è autore da Nobel vero, non assegnato per sbaglio, intendo. I suoi libri spesso sono tristi, scombinati, folleggianti, dalla sintassi personale, senza punteggiatura con la sola maiuscola a scandire un dialogo e separare un personaggio dall'altro, eppure hanno una forza espressiva che nella letteratura contemporanea hanno in pochissimi, forse nessuno.

“- Un giorno o l’altro mi troveranno su questa spiaggia, divorato dai pesci come una balena morta - mi disse nella via della clinica guardando gli edifici sbiaditi e tristi di Campolide, i monogrammi di tovagliolo delle insegne luminose spenti, i resti di porporina delle feste natalizie delle vetrine, un cane che frugava, in quel mattino di febbraio”.

Grande romanzo dal titolo perfetto. Difficile, elegante, crudo, bellissimo. Rui S. è un uomo che fa una tremenda fatica per vivere, siamo a Lisbona, più di trent’anni fa (il libro è del 1981 ma pubblicato nel 2010 in Italia). Nella sua testa l’idea di lasciare la sua seconda moglie e per farlo vuole portarla dove il fiume incontra il mare, dove si addensano gli uccelli in volo e sulla sabbia, alcuni, muoiono. Da bambino ha rivolto una domanda bizzarra a suo padre: spiegami gli uccelli. Egli l’ha spiegato con immagini poetiche benché fosse un uomo d’affari; gli uccelli hanno le ossa fatte di schiuma di mare e quando muoiono volano a pancia in su nell’aria, con gli occhi chiusi come le anziane durante la comunione. Suo padre possiede un’azienda, colleziona uccelli, farfalle - le uccide con una goccia bluastra sulla testa per conservarle intatte. Lui non ha voluto seguirlo, si è messo a insegnare Storia. La sua prima moglie lo ha lasciato in un weekend, era innamorato e non voleva staccarsi da lei e dai suoi due figli. Ora lui vuole lasciare la sua seconda moglie allo stesso modo, mentre vagano fuori città. L’ha conosciuta all’università, è del tutto diversa dalla prima, è una militante, voleva convincerlo della giustezza del fatto che gli oppressi vanno salvati, sostiene Godard, Orson Welles. Lui non lo sa davvero più cosa ama. Le sue sorelle gli rimproverano di non aver seguito suo padre, il giorno in cui è morta sua madre si mescola alle parole scambiate col suo vicino, un uomo tozzo di 33 anni, vessato dal mondo. Tutto si confonde e ora non ha più senso capire che non è più lui che la sta lasciando. Pensa al circo, ai trapezi, e la sua vita stessa sembra un circo sfatto di voci, di risa, di domande.

Non hai mai ammazzato una farfalla?, Non ha mai capito il Secondo Principio della Termodinamica, Può darsi che la malattia della madre abbia inciso in tutto questo, La storia con te è stata come una parentesi nella mia vita. Non si tratta di amare, no.

“Le poche barche e la città in fondo, imprecisa come gli occhi dei ciechi, ma poi gli uccelli, i gabbiani e le anatre e i volatili senza nome del Vouga gli invasero le gambe e le braccia”. -

It's been a month since I read this, and it still haunts me. It's like Fellini and Max Ophuls and Dennis Potter conspired with each other and then dictated a book to David Foster Wallace (and told him to skip the footnotes).

I know this a biting satire of post-Salazar Portugal, but how rare is satire so emotionally powerful?

What a genius Antunes is. -

It is my second novel by Antunes, and I find his voice overwhelmingly addictive and totally unique. He is easily switching from the first to the third person narrative within a single sentence. I've never came across with such a voice before. The language is also very metaphoric and poetic. Metaphors are strikingly original.

This particular novel is about the unravelling of a 3o year old man caught up in the contradictions of his family and his own convictions, his perceived spineless and struggling to find the way out. It is such a bleak, but such a beautiful novel. There is also an element of the absurdist humour in it which comes into play in the least expected moments.

It deserves much more detailed review. But for now, I would just leave the passage, which might be read like a stand-alone poem.

"A shapeless shadow grew, approached, and suddenly came into focus in my head: we are separating. Marilia’s breathing fanned the furniture in a kind of rage, the ceiling seemed ready to fall on our heads in dusty chunks of plaster, panes of glass were clinking somewhere, the air in the pipes signed and the sound echoed for a long while in silence, vibrating like a violin: we are separating we are separating we are separating, repeated the caws of the birds with mocking irony; a dog barked ferociously under the window (We are separating); the pine trees waved at the one another with their long dark arms in which the crouching night hid (We are separating ); a chilly breath in the tops of the eucalyptus trees whispered its meaningless secret: we are separating."

I only wish I could read it in Portuguese. But this novel is really well translated, especially compared with

The Return of the Caravels, another one by him I've read. -

Ugh. Dreary. Straight, virtually diary-entry realism spiced with unnecessary tense- and perspective-shifts and self-conscious Felliniesque flourishes. To have characters suddenly intrude in circus costume with mockumentary-style soundbites (‘“There’s always hope,’ yelled his father, dressed in tails and a bowler hat, pulling a stream of coins from the noses of the children in the first row”) might be unique in a prose context, but I feel as if I’ve seen it repeatedly on film. Added to which, why should I care? I don’t see an ounce of imagination in this, and the narrator’s cynicism (familiar from a hundred self-pitying ‘I’ novels) is repulsive. 80% of this couldn’t be more familiar. The other 20%? Maybe it redeems the rest, but I wouldn’t know, I stopped at page 50.

-

Tour de force di scrittura (ottimamente tradotto da Feltrinelli) che a poco a poco avvince e avvinghia, mettendo in scena l’incastro dei miseri destini del protagonista Rui e delle sue due donne, personaggi tanto sgradevoli (di una sgradevolezza sia fisica che morale) quanto veri. Qualche fuoco d’artificio narrativo di troppo (soprattutto alla fine del libro) ma sicuramente un grande romanzo e un grande autore.

-

he should so clearly be the second portuguese to win the nobel prize for literature. if roth, pynchon, delillo, or updike win the award before him, the swedish academy hates freedom.

-

Adoro este livro. Tem tudo presente: A família elitista onde a personagem principal (Rui S.) já não se encaixa, mas onde foi muito feliz no passado. À boa maneira Portuguesa, a personagem continua a viver aqueles momentos passados, sem nunca colocar os olhos no futuro. O Rui é derrotista, sem esperança e um "deixa andar". As suas decisões são incompreendidas e incoerentes na perspectiva dos outros, mas plenamente justificadas na sua mente. Rui S. não é cobarde, fraco ou limitado. É complexo, compartimentado e um romântico. Apenas o compreende no final, quando percebe que afinal ama quem esteve ao seu lado e de quem se pensou separar.

É também um retrato da relação entre os jovens casais no final da década de 70 (que eventualmente se mantiveram semelhantes no início dos 80s), por oposição ao conservadorismo das gerações anteriores, estas plenamente adultas na altura do regime. Na narrativa vivemos também um pouco da eterna Lisboa desta altura.

Um dia uma professora disse-me que António Lobo Antunes merecia um Nobel. Até ler (viver!) este livro, não percebia bem porquê. -

Este é o quarto romance de António Lobo Antunes, escrito em 1981. Por comparação com os anteriores, marca decididamente uma mudança nas temáticas abordadas e na forma de organiza��ão do discurso narrativo. Ao contrário das referências mais explicitamente auto-biográficas, como a guerra colonial, o período pós-revolucionário e a experiência do exercício da psiquiatria, encontramos aqui a autópsia de uma figura simultaneamente ridícula e trágica.

Rui S., casado em segundas núpcias com uma mulher que não ama mas que preenche o vazio decorrente de uma dissolução abrupta e não querida do seu primeiro casamento, é um frustrado professor de História que vive esmagado entre o repúdio da família, em especial do pai – importante empresário do antigo regime – e o desprezo das mulheres com quem casou. Neste quadro de marginalização e abandono, a sua incapacidade de lidar com a inadaptação familiar e social, a sua passividade atávica e a pusilanimidade do espírito, associados a uma ânsia de absoluto em si existente, mas absolutamente inalcançável, agravada pelo cerco social a que é sujeito, conduzirão a um itinerário de falhanço existencial, culpa, desvinculação, abandono e, por fim, desistência e/ou libertação.

Para além do excelente recorte psicológico das personagens, porventura o aspecto mais interessante e cativante deste romance é a complexa e filigrânica técnica narrativa empregada pelo autor. A narração apresenta-se numa densa e admirável estruturação polifónica, em que diversas vozes coexistem e se entretecem em permanência, entrançando – de forma quer cronológica, quer anacrónica – a narração dos eventos exteriores com os pensamentos explícitos e imagéticos da personagem, com as suas memórias e deambulações mentais presentes e passadas, com crónica e relatos de terceiros e, progressivamente, com a materialização de um drama grotesco e irrisório, em que tomam parte todos os que povoam o universo do acossado Rui S. e que servirá de palco a um desfecho desvendado desde o início.

Quer pela temática, quer em especial pela riqueza e complexidade da textura narrativa, este foi, até à data, o romance de António Lobo Antunes que mais apreciei. -

Lobo Antunes es una puta maravilla. Este libro pesado, lento, húmedo y gris es un descubrimiento tardío (mi leitmotiv es llegar tarde a todo) para mí y el primero con el que conozco a este autor del que quiero leer toda su obra ya mismo. Acerca de los pájaros es la historia de Rui S., la personificación del peor destino que puede tener un hombre: la medianía absoluta. No mediocridad –una palabra con demasiada carga en esta época donde el “éxito” es la meta por excelencia y cualquiera que no aspire a él es un imbécil o un desubicado–; medianía. Es un burgués que no quiso serlo por completo, negándose a tomar las riendas de la empresa familiar para estudiar historia y literatura, pero tampoco se atreve a la militancia abierta y el partido comunista lo relega. Esta incapacidad de completar algo permea todas las áreas de su vida, particularmente sus relaciones sentimentales, de las que hace un martirio permanente. Odia a su ex mujer y a su mujer actual, una militante comunista desaliñada y brusca, tanto como ellas a él. Se acerca a ellas como un perro sumiso para luego enfurecerse porque no tiene autoridad. Sin embargo, su relación más tormentosa es con su padre, hombre reaccionario a quien admira y desprecia por igual y de quien sólo recuerda un rasgo tierno que compartían: el interés por las aves. Su vida va de tratar de recuperar esa ternura que nadie más que él recuerda y que con el paso de los años no es más que una anécdota ridícula. Es un mensaje terrible: la ternura –su búsqueda, su imposibilidad– puede matar a un hombre.

-

“As mulheres detestam os homens demasiado previsíveis, adoram um coeficiente de surpresa”

“As pessoas que por mais que procurem não encontram um sentido para a vida”

“[…] A Madame Simone tinha um trisavô marselhês, e nutrira quarenta anos antes uma paixão tumultuosa por um trapezista de Nice que a enganou depois com uma contorcionista de Sete Rios e lhe deixou de herança uma filha da minha idade professora primária em Mirandela, a criatura mais míope e borbulhosa que em toda a minha existência me foi dado conhecer, as lentes dos óculos dela ultrapassavam em espessura as vigias dos navios e exprimia-se como se estivesse a explicar que um e um são dois a uma turma de orangotangos mongoloides, com dor de dentes, sarna e hepatite […]”

“uma vez consegui arrasatar a Tucha à Estufa Fria depois de horas de poderosos argumentos botânicos (Parece impossível que nunca tenhas lá ido, há fetos lindíssimos desenhados pela Chanel e importados directamente de Paris, viste com certeza as fotografias deles na Vogue)” -

When Lobo Antunes gains objectivity, he loses quality. It's a geometric progression. In this book he tells a story all too often and leaves poetic prose aside. Even without the usual pretentiousness, Lobo Antunes has a lesser work here.

-

Dice António L. Antunes que él escribió este libro en seis meses; y yo le creo.

Acerca de los pájaros es de un 'estilo' desarticulado y sin relación ninguna que no capturó mi atención porque simplemente uno nunca sabe qué cosa está leyendo. No hay anécdota clara ni acciones suspensivas, uno se pierde fácilmente porque no es posible diferenciar las imágenes pensadas de las reflexiones o los recuerdos, y nada tiene coherencia con el párrafo que le sigue; la voz narrativa cambia de género y de persona así sin más, sin aviso ni justificación aparente. Uno continúa la lectura esperando a que surja algún hilo conductor que enlace o que dé conexión a este bombardeo de imágenes tan aleatorias y separadas, pero ese hilo nunca llega y el lector termina ahogado en una serie de pensamientos confusos y desordenados.

El libro termina siendo una larguísima puñeta mental, un desvarío que no se acaba. Es como estar escuchando a un loquito que mezcla lo que recuerda con lo que piensa con lo que quiere, y luego se le olvida de qué estaba hablando y empieza otra vez su avión.

Sugiero que se lea este libro con la libertad y el placer de nada más estarlo hojeando: brincándose páginas, regresando al azar, a sabiendas que en todo el libro nunca pasa nada. En ningún momento se debe buscar un desenlace ni una anécdota real, porque la imagen trasciende al discurso y la lectura se convierte en un mar interminable de cosas escritas porque sí. -

Iniciei-me na escrita de António Lobo Antunes com este livro e não há dúvida de que me sinto um iniciante. A "Explicação" na sua intenção e construção desafia uma explicação simples e o propósito do livro pode bem residir aí, em mostrar como a vida de um indivíduo frustra a maior parte das classificações e explicações. Ao nível da escrita, é notável o trabalho de tecelagem dos vários tempos e personagens da história. Gostei particularmente dos detalhes que o autor coloca na descrição de algumas cenas e que (ainda hoje) pintam tão bem o quotidiano lisboeta.

-

While not my favorite book by Antunes, I'm still shocked and awed by his ability to overlay complementary scenes from across time within a single paragraph and the way he conjures the perfect imagery to describe a situation - turning a hospital visit into a circus? Frighteningly accurate.

-

Another of the major Portuguese authors António Lobo Antunes

-

Adoro ALA mas este livro é demasiado confuso. Vou deixá-lo de parte durante um tempo.

-

Like the ever present fog, dirt, hopelessness and lack of faith and direction , it soaks you in, makes you crawl while reading, but leaves with strange optimism of understanding we're all flawed...

-

A challenging book. The way of writing extraordinairy. We follow the last days of the hero from the view of so many people, people that he knew, people that were his family and people that are watching his life as in a tv or a play. A man who goes against the wills of his family, who seems to be a disappointment for his bourgeouse parents but not a lot better for the socialist party he seems to follow. A bit difficult but still interesting book.

-

Desarticulado, y con una cantidad de imágenes bellas pero sin propósito claro. La mitad del libro son listas y listas. Parece que el autor es adicto a enlistar cosas, recuerdos, imágenes. Algunos dicen que es el encanto del libro, a mí me parece que simplemente es una cualidad que lo hace poco atractivo.

-

"Os barcos ancorados remexiam com moleza as ancas."

"...o vento de navalhinhas do inverno a barbear a bruma,..."

"Quais as asneiras?, pensou ele, intrigado, vasculhando o súbito, angustioso, enorme vazio da memória até onde o braço da lembrança conseguia."

António Lobo Antunes, Explicação dos Pássaros -

A simple man with a simple ambition (to know more about birds), who is trapped in his own overambitious- bourgeois-family's ambition and stuck in a frame of his left-wing-activist wife. Most of Antunes' characters are ended up in their most tragic and pitiful fate, this one is no exception. But we can imagine him in different circumstances and different era and he could be a better man.

-

como pocos libros

-

Pela primeira vez... Já estava farto.