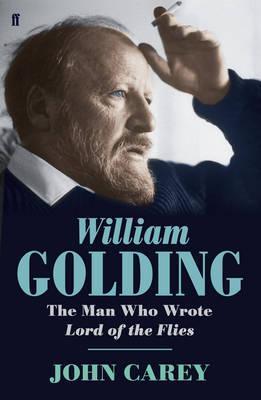

| Title | : | William Golding: The Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0571231632 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780571231638 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 592 |

| Publication | : | First published October 1, 2009 |

| Awards | : | James Tait Black Memorial Prize Biography (2009) |

William Golding: The Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies Reviews

-

-

You know what to expect in advance from John Carey. With any other author that would be a bad thing. With Carey it's part of his integrity.

In the introduction to Original Copy, his 1987 selection of reviews and journalism, Carey reminds us that 'given the nature of subjective nature of literary judgement, the reader has a right to know what sort of person will be laying down the law in the rest of book - what his quirks and prejudices are, and what sort of background has formed him.'

So with this, Carey's long (and eagerly) awaited biography of Golding, you expect the law to cheer on grammar schools, vegetable gardening and divided personalities, and sneer at snobbery, Dons, and magical thinking. Golding's dabbling with anthroposophy, you think, is in for a particular thrashing. And as for Golding's public-schooled contemporaries at Brasenose College...

That’s half the fun of course. Flaubert said that when you write a friend's biography, you must do it as though you were taking revenge on his behalf. Whether you agree Golding was the abject literary outsider that Carey makes him out to be, you still share his partisan sense of outrage. Take the film critic C.A. Lejeune's response, in chapter fourteen, to Pincher Martin: 'To me it belongs to a class of reading that I deplore, which looks at nothing except what I call the underbelly of the human body, and it sees nothing except what I call the nasty side of it, the horrid side of it.' Behind that you can hear the objection of every person who has ever junked a great book because it's 'too grim', 'depressing' or - this above all - 'doesn't teach me anything'. Carey's response makes gratifying reading, as does his response to Auberon Waugh ('so clearly the voice of a Young Turk eager to make a splash'). Watching him go, you feel that vengeance isn't just being served, it's being accompanied by a string quartet.

But if Carey is deadly on the attack, he's even better in defence. That may surprise some people. This may be the compassionate book Carey has written. People expecting him to tear Golding's beliefs to pieces, even by implication, will be disappointed. In a way, he celebrates them. As with Lawrence and Orwell, Carey sees self-contradiction not as a blemish, but as a key to greatness. With Golding, it was his constant inner struggle between faith and reason that breathed life into his writing.

Much has been made of Golding's early scientific optimism and belief in progress, influenced heavily by his father Alec, and how World War II turned him towards pessimism and religion. And, of course, original sin ('Man produces evil as a bee produces honey.'). But the division was already in place. There were the supernatural visions or hallucinations that baby Golding saw. (An angelically radiant cockerel appears to him in the cot.) Where Golding's father was a kindly, unassuming man, his mother was an unstable collection of temper tantrums and Celtic superstitions. The tension between the two caused him, Carey suggests, to see reality as the battleground of warring viewpoints. 'Both are real', as Sammy says in Free Fall, but 'there is no bridge'. Golding's fiction and essays will each in their way continue to report on that battlefield.

If Golding had his theme, he still needed a vehicle to express it. By 1953, he had written three books in his breaks, lunch hours, and holidays, and seen them all repeatedly rejected. The school he returned to offered nothing but grinding, purposeless routine. If Golding believed he was a third-rate teacher, just as he believed he was 'a monster', he seems unduly hard on himself. Was he the only teacher who ever rushed off as soon as a lesson was over, who didn't think the world of every last one of his pupils, and who didn't look at a small hill of unmarked books with despair?

So Golding started another book, which started out as a skit on the bedtime stories he read to his children. Doubtless some insights prompted by his pupils found their way into the novel. (Though Golding, as Carey points out, never taught choristers.) So, for that matter, did World War II. The work gave him new energy and drive, and made the real world look grey and dull by comparison. He had total faith in it, feeling it to be his truly first original work. In it, following a nuclear war, a group of school children would find themselves marooned on a desert island, with only wild boars and a dead parachutist for company. Somewhere a big shell would be involved, and so would a Christ figure, performing miracles and offering himself as a martyr. It would be the Robinson Crusoe for our time; it would be the novel that would make his name. It would be...Strangers from Within.

I'm not going to say what happened next, especially for those who haven't read Charles Monteith's account in Carey's earlier book William Golding: The Man and His Books (and which Ian McEwan mentions in his novel Enduring Love). Carey reworks it into chapter twelve, just as he reworks his account of The Inheritors, from his earlier book Pure Pleasure, into chapter thirteen. You really have to read this one for yourself. It's just too good not to. Suffice to say if Golding's life had been a film, Charles Monteith, his publisher and a model of human patience, tact and reserve, would have more than deserved the Oscar for best supporting actor. It's not for nothing that Carey devotes his last paragraph to him.

Also heartening is Carey's enthusiasm for all Golding's works, published and unpublished. Carey has his opinions, and maybe you'll share them. Maybe not. I never liked Free Fall much (and it seems to be the hardest of Golding's novels to find in the shops), nor The Paper Men and The Pyramid. To me, the most powerful of Golding's novels were his earliest: Lord of the Flies, The Inheritors (which anticipates Craig Raine and the 'Martian' poets) Pincher Martin, and The Spire. The most polished were the three novels that comprised the Sea Trilogy. If you agree with Carey or not, we're still left with a timely and powerful corrective to the rather quaint idea that Golding was a one-hit-wonder, or, worse, a 'minority taste'.

Carey praised Orwell for admitting that most people liked to read about murder. I praise Carey for admitting what most people like to read about a writer: the brute facts of how he produced his work, and how much he made from it. Carey doesn't omit the figures: advances, royalties, sales figures, foreign rights, film rights - all here. The sources couldn't have been better, the writing more concise, the breadth of insight and intelligence wider. Although I would have liked a reference to the work of Kevin McCarron somewhere here, especially on Rites of Passage, this is by far the best literary biography I have read this year. Since I have read Patrick French (on V.S. Naipaul), Martin Stannard (on Muriel Spark) and Zachary Leader (on Kingsley Amis), that is the highest praise I can think of. Absolutely not to be missed. -

John Carey subtitles this biography The Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies because that one novel, his first, defined his literary life. Golding himself regretted the fact, feeling his later work far surpassed it in quality, even though from his beginnings with the inspirations in which boys he taught and understood so well and used as models for a descent into savagery to his ending novels, the Sea Trilogy, his major theme of evil loose in the world never wavered much. His novels were informed by his interest in ideas rather than people, in seeing mankind against a cosmic background rather than a social one.

William Golding is one of those novelists whose books have been long familiar to us because their fame rests on their assertions about the human condition. They've been widely read for that reason, and for their stylizations. Carey's biography is a successful one in that it presents an interesting portrait of the writer in the midst of his motives and influences as well as cogent analysis of the individual novels. And it's successful because it makes one, even if a fan acquainted with the work, want to go back and read it again. But the book does disappoint in a couple of ways. A naval officer during World War II, Golding served in the Atlantic and as the commander of a LCT used to launch rockets against shorelines to be assaulted. Given that records may be hard to obtain today and that these years may have been pre-diary, I thought Golding's wartime service too sketchily dealt with. Also, it suffers, like many biographies, from an abundance of information in the later years. Carey falls into the trap; when his subject became so public that too much is known of him not to mention, he tries to catalog it all so that his narrative of the life is turned into a survey, a torrent of facts and events rather than meaningful analysis of the man and writer he'd become.

But if Carey fails to make Golding as unique as perhaps he was in life, he explains the novels in such a comprehensive manner that reading the biography becomes worthwhile and engaging. -

I have to give this biography five stars because of the sheer amount of detail it includes and the way in which the enormous complexities and contradictions of Golding's life are etched out, inch by inch.

I didn't greatly enjoy reading about Golding, for all that, and almost gave up after the first few chapters. No sooner do you find yourself in sympathy with the man than you have that sympathy thrown back in your face. He was brilliant in his own way, but it's not an appealing brilliance. He behaved like an idiot in many areas of his life, and though in the Postscript Carey gives an explanation for some of this, it's remains puzzling as to why he was so self-defeating in so many ways, even in such simple things as taking a map so that he didn't get lost when driving, especially abroad.

To my surprise, I found I'd only read two of Golding's books, Lord of the Flies of course, and The Spire. From memory I enjoyed both of them, but it's many years since I read them. Of his considerable number of other books and writings, I have no acquaintance. And in spite of the enthusiastic way Carey writes about each of them, I'm not sure that I want to chase them up. I may be wrong in thinking that, and may need to revise that idea.

The book is perhaps at its best in showing us something of the way Golding wrote, his frustrations with what he wrote even when it was good, his procrastinations, his feeling of never being able to write another book, his unwillingness to read either good or bad reviews, his endless drafts and changes even to the final copy. He was greatly fortunate in having Charles Monteith as his support at Faber and Faber, the publishing house he worked with throughout his life; Monteith was more than an editor, he was a great friend and had a considerable eye for what worked in Golding's writing. Only a few writers have such a champion, and Golding perhaps needed such a champion more than many writers.

Carey has uncovered endless stories and incidents; he has used the vast journal that Golding wrote to clarify much that went on in the latter's life - although there are times when the details of Golding and his wife's overseas trips become overwhelming. Carey never stints, and this work is an extraordinary testament to the creative work of a biographer. -

It has become something of a summer holiday habit with me to read the vast biography of some writer whom I admire. I suppose it’s the only time I feel that I have the space and energy to take on reading tasks of this scale. As a writer, I find it hugely instructive but humbling also to be in the presence of genius. And make no mistake, in this instance, that overused term is apposite. What might one give to have written a sequence like Golding's first five novels? Lord of the Flies, The Inheritors, Pincher Martin, Free Fall and The Spire… Okay, so Free Fall let’s things down a little, but it doesn’t diminish the monumental achievement. The leaps of imagination and the poetry of his writing, the relentless elemental themes of evil and irrationality… And then the return, in his twilight years, with the masterful To the Ends of the Earth sea trilogy. This I also read in a summer holiday binge many years ago, looking out on a rural walled garden as Golding did. Here, we learn something of the Mephistophelean pact Golding made in order to produce these works.

If you love the novels of William Golding then this first biography of the great writer will fascinate you. If you’ve only read Lord of the Flies or indeed nothing of his oeuvre, I suspect you’ll find the book less enthralling. And if you conflate him with William Goldman, as an American acquaintance of mine did, then it’ll probably have no appeal at all. Drawing on Golding’s previously unseen journals and letters to his editor at Faber, we gain fascinating insights into the construction of the novels. I had read somewhere that he would write a draft, then start all over again, and then again and perhaps a fourth time. Light is thrown on the whole process here. We learn about abandoned projects and early drafts, many of which Carey declares tantalisingly are in urgent need of being published. It’s also a real bonus to have a round-up of the contemporary reviews for each work (items which Golding avoided like the Black Death). We get a genuine sense of the man himself, as far as this is possible with such a private individual (after all, Golding’s novel The Paper Men concerns his alter-ego, Wilfred Barclay, stymieing a would-be biographer’s attempts to write about him). Such a person ‘won’t reach the root that has made me a monster’, Golding notes in his journal and Carey laments that ‘I do not know why he thought he was a monster’. He suggests that Golding created the mask of a ‘Captain Birdseye’-type figure and this was very definitely the impression I gained.

I make my appearance on p508. Admittedly, it’s in a crowd scene with 800 or so others. Golding reads Chapter 17 of Fire Down Below at UEA in Norwich on 27th October 1992, as part of my alma mater’s annual season of interviews and readings with noted writers. “The queue for signing afterwards stretched ‘coil on coil’,” the book reports. When my turn came, I produced my second hand copy of The Spire and announced “A very fine novel, if I might say so, Sir William.” “A very fine spire,” he replied. “404 feet, I believe.” “Yes, that’s right.” Fortunately, this latter part isn’t recorded in the biography. My ex then brought forth my second hand copy of Lord of the Flies, the one with ‘Write Piggy essay’ inscribed in the front. “And did you ever write it?” Sir William asked her. I forget her mumbled answer…

Having written the biography of a creative, I’m acutely aware of fans who snipe from the sidelines, pointing out this inaccuracy and that, so I’m not going to nit-pick too much. I did feel that the accounts of the writing tours went into too much detail and we lost the overall narrative at these junctures. It’s opinionated at times in terms of ‘the canon’. Carey finds it remiss of Golding not to have read Hardy, implying that any right thinking person would find this a fault. Perhaps Hardy’s work didn’t appeal to him. When Golding had become rich and famous towards the end of his life, he met a series of privileged persons in Cornwall with marvellous houses and gardens, about which the descriptions feel distinctly unctuous. I’m told that publishing houses simply don’t provide editing services for writers in the way they used to. Certainly, Golding’s editor, Charles Monteith, who played a huge part in his writing and personal life, would have picked up on some of the inevitable typos and continuity errors here. At one point, Golding meets President Mitterand, who becomes President Chirac in the next paragraph, some twelve years before his investiture. If you look up Jacques Chirac in the index, who after all is only a typo in the book (Golding was dead by the time he assumed the presidency), he is referenced on p424, where neither man is actually mentioned.

Carey is a critic of great distinction and he has compiled Golding’s life story with enormous thoroughness and erudition. It’s beautifully written. In sum, I found it a page-turner. Carey hoped the subtitle (‘The Man Who Wrote…’) would fish in the uncommitted who were unfamiliar with Golding’s oeuvre and make them wish to explore it further. On this level, I’m not convinced it can succeed. -

The simple yet seldom achieved foundations of a good biography are thoroughness and insight, and this book not only actualises those laurels but goes far above and beyond them. Golding is presented as a whole - a full, complex and conflicted human being, possessing intelligence, talent, morality, wit, quirks and darknesses - with tact and tenderness, but also with unflinching yet non-judgemental honesty. The depths of Carey's research and respect are obvious and make the book the masterpiece it is: a biographer lacking his sensitivity, perspicacity and considerable writing talent would have failed William Golding as both a subject and a man, and left us without this incredibly special book. This is an indispensible, enriching and treasurable account of Golding and his life that takes away all cliché from the idea that a book can make you feel closer to a person - by realising the notion perfectly. With Golding having passed almost 20 years ago, this is an especially rare and important feat, for those of us who care now and those who will in the future.

-

William Golding by John Carey is a biography of the man who is best known for writing Lord of the Flies. It was one of the first assigned books in school that I actually really liked (the other was A Separate Peace, assigned by the same teacher). Twenty five or so years later I'm still mulling over the book and seriously contemplating a re-read of it.

I can't recall where I heard about this biography, but I do know I wanted some idea of what made Golding tick. I also wanted the story behind his most famous novel.

Before Golding found his niche as a writer he was a teacher. His time in the trenches gave him the insight he needed to create believable archetypes.

The remaining half of the book covers the rest of his life and the other books he wrote. I'm curious enough about his other books to want to read them. I picked one at random from the library but it was so far removed in style from Lord of the Flies that I didn't make it through the first chapter. My next plan of attack is to go through his books in order when I have the time. -

This first masterful biography of Golding, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1983, serves as an indispensable guide for anyone who wants to know about the man who wrote a modern literary classic, and about why and how he created it. Aided by unfettered access to Golding's private papers, Carey provides a meticulous but rather sobering investigation of an individual considered, while in school, "not quite a gentleman." Golding was well into his forties before he experienced his phenomenal success, and he nursed his grievances against a world that was late in recognizing his greatness. He did not consider himself a good man; indeed, he believed that his renowned novel reflected the evil within him. Carey hesitates to reveal the dark side of his subject, but provides an empathetic portrait of a troubled man. And, good critic that he is, he explains why Golding's later novels, for example, The Paper Men, were not entirely successful. Carey has produced a cutting-edge work exemplifying the best features of literary biography.

-

John Carey has written an eminently enjoyable biography of this complex, intelligent and fascinating man. He shows a deeply flawed man with a wicked humour, while at the same time portraying Golding sympathetically. The way John Carey delivers Golding's wit in his own narrative is, in itself, a treat.

If, like me, the only Golding you've read is Lord Of The Flies, then this book will inspire you to read much more of Golding's writing. -

From BBC Radio 4 - Book of the Week:

Christian Rodska reads from John Carey's biography of the Nobel Prize-winning author -

Golding is one of my favorite writers and an inspiration, which my ratings on this site may not indicate, as his oeuvre as a whole is more beautiful, imposing and haunting than most individual volumes from it show. But I would and will reread anything and expect every book will grow with rereadings.

I enjoyed Carey's biography and am grateful for its author's research but it's hard to feel satisfied -- it makes me wish there were complete publications of Golding's massive journal and the Golding-Monteith correspondence.

Some things of interest:

Golding liked books by Jerzy Andrzejewski (!) (Ciemonści kryją ziemię), Hermann Broch (The Death of Virgil, "which he dismissed at first as 'the higher rant,' but reread back-to-front so that he could savour each poetic phrase, and began to wish he had written it himself"), Kazuo Ishiguro (An Artist of the Floating World and The Remains of the Day, "'a quite seductive newness,'" "the English novel could, he thought, safely be left in their [Ishiguro, Byatt, Barnes] hands"), and included (among others) Lawrence Durrell, Anthony Powell, Iris Murdoch, T.H. White and (shortlisted but not finally taught) Ivy Compton-Burnett on a reading list for a modern British novel class he taught at USA's Hollins College in the '60s, so insistent on Durrell (Justine, if the Alexandria Quarter was too difficult to get ahold of) he was ready to lend students his own copies.

He may have been familiar with John Cowper Powys's fiction or one volume at least -- when George Steiner, champion of Powys but lifelong disparager of Golding, wrote that Darkness Visible owes too much to Voss and JCP, Golding shot back, "'some damned reviewer derives me from Patrick White and the Glastonbury Romance. The silly sod cant see that I derive from knowing Australia and Glastonbury.'"

He didn't generally get on with animals ("'a man's bed is a preposterous place for an otter'"); negative experiences included being charged by an elk and almost bitten by a horse he and his wife had just nursed to health.

Golding was a master of premises, eclipsed therein only by his mastery of finished products. The three unpublished books before Lord of the Flies don't sound attractive (Charles Monteith read Short Measure but declined to publish, thinking it lacked "'imaginative fire'" compared to Flies) but there appears to be a host of fascinating, unfinished work across the years after. Among them are two completely different novels under the same title, the first In Search of My Father a wild fantasy Golding worked on before and after The Inheritors, the second In Search of My Father hailing from the long years that separate Clonk Clonk and Darkness Visible and narrating a character's "'scandalous' adventures in the 'stews of some middle-eastern seaport,' before landing up in the Greek islands among the expats." Then there's the start of a fascinating book in 1991, set in Philistia among marauding Israelites, about a false and real Herakles and interfering angels. The fertile Scorpion God period suggested additional stories, "'one on the fall of the Spire and the second on the building of Stonehenge," with a third, tentatively titled I Said: Ye Are Gods "about overpopulation and pollution ... the text would start normally and become, as the story went on, 'an illegible mass of the smallest (diamond?) print possible,' graphically illustrating population explosion." The Pyramid, moreover, Golding so enjoyed writing that he conceived of the book when preparing for publication as an indefinitely-to-be-expanded storehouse of Oliver stories.

To the Ends of the Earth, the gorgeous tale of Edmund Talbot, began with Colley's journal; Edmund himself was an afterthought! And it was largely written to serve as comfort, which helps explain its warmth: Rites of Passage to offset the difficulty of Darkness Visible and Close Quarters in the same relation to The Paper Men.

Of all his and his wife's travels, or "globe-trotting" as Carey calls it, bogging down later chapers of his book with meticulous itineraries, it appears Australia, Canada and India were the places to leave the strongest impressions. There are lovely selections from Golding's journal about the three. "In the Melourne Botanic Gardens he and Ann found the tree trunks -- silver, smooth and tactile -- even more extraordinary than the foliage, 'like the trees of nowhere else' ... He could find no words for the coral and fish colours, and asked them aloud, 'How do you praise God?' They were Gaia's children, he concluded, and lived in a different universe from him."

Golding's spiritual visions and dreams were utterly extraordinary and some of their power survives in Carey's telling; I read them with chills. -

Carey has done an outstanding job of giving the reader an intimate portrait of William Golding, the man as well as William Golding, the author. Obviously no-one can really get inside the head of another but from his personal interviews, his lengthy discussions with friends and family and his careful dissection of Golding's writings and his journals he gives us a fairly complete picture of a complicated and conflicted man.

Golding was acutely aware of his position in the social pecking order and always felt as though he had to prove himself to the world. In spite of that it seems as though he could be just as much a snob in looking down on those he felt were not his intellectual peers and he also petitioned hard for the honor of being bestowed a knighthood. It seemed he was always looking for and needing affirmation.

While he put on a blustery old carefree salty sea captain persona he was actually full of fears and phobias and filled with self-doubt about his writing. He was also given to a good deal of dissipation - drinking to excess - followed by remorse.

Carey shows the history and creative process behind his stories - how his own personal experiences were often woven into the novels - and this gives the reader a whole new perspective of the works of Golding. All in all, a very readable biography. -

At last, I made the effort to read Golding's biography and what a pleasure; a few years ago, I read John Carey's The Unexpected Professor and liked it and knew I should be in for a treat with 'The Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies'. Such detail. As an example, being Cornish and of a certain age, it wasn't just the references to the likes of historian A.L. Rowse that meant something, so too did David Treffry. As for Tullimaar, Golding's last house, I've known of it for decades.

In reading this biography, I learned something of other characters, like James Lovelock, who lived for a time in the same Wiltshire village as William Golding. It had never occurred to me that it was somebody else who had provided the name for what Lovelock is probably most famous for, viz. Gaia; it seemed an obvious suggestion for William Golding to make on a walk with James Lovelock.

Then, in terms of style and technique, I learned that Joseph Conrad was the first novelist to use a disrupted time sequence in his works. It had never occurred to me who might have been the first author or when this might have first occurred.

Reading this excellent biography inevitably raised a number of thoughts and this is where the internet is remarkable; there are so many sites to look at: Judy Golding can be seen discussing her father at Tullimaar on YouTube, as can Melvin Bragg from the early days of The South Bank Show. Well done, John Carey, this really is an excellent biography. -

Very well researched and well written biography about the man and the writer, William Golding. If you wish to read a particular work, I would NOT recommend reading the chapter pertaining to that piece before reading the work or unless you do not mind spoilers. John Carey has an extensive and impressive list of sources at the end of the biography.

-

An interesting & influential man, and Carey offers a good biography of him. Having contemplated Flies, I’d wondered about the dark cynicism — his experience teaching at two English boys’ grammar schools answered the question.

-

As the title suggests not everybody would know who William Golding was . I am not even sure that " the man who wrote " Lord of the Flies " means an awful lot nowadays . It used to be a staple on school eng lit . reading lists and the author did win the Nobel prize for literature . However his era of writing is a bit recent to be re-assessed and he has gone out of fashion .

This is a solid biography and Golding seems to have been a decent enough old cove but after the early years led to world wide fame , the tale of literary lionisation , lectures and writing is none to exciting . I suspect also that since his children are still alive the biographer may have avoided certain sensitive family areas .

Golding belonged to a certain era when the BBC Third programme catered only for highbrows and the broadcasters probably wore dinner jackets in the studio , an era of Faber and Faber , T.S.Eliot and Penguin books with orange covers . -

I bought this book after going to a talk by the author. Like so many other people, I had only read Lord of the Flies, but I'm now determined to read some of Golding's other work. After a slightly slow and confusing start about Golding's grandparents and parents, with slightly intrusive quotes from Golding's journals, the biography proper started, picked up and quickly becamse fascinating. An irascible man with an extraordinary vision, the drafting of his novels and subsequent revision process is covered in some depth, but so too is Golding's war career and nonchalant approach to school-mastering. Carey was given unprecedented access to Golding's journals but also to the Faber archives and many of Golding's contacts at universities around the world, so the details provided and Golding's feelings about his various escapades, as written in his journal, add to the richness of the text. If it wasn't for the slow start, the book would have been a five star.

-

The first biography of the publicity-shy author William Golding, whose debut novel was rejected by many publishers before going on to sell over 20 million copies in the UK alone.

Drawing on a vast wealth of previously-unpublished material in the Golding family archive, John Carey explores the life and career of an often violently self-critical novelist who won the nobel prize for literature.

Abridged by John Carey. Read by Christian Rodska. Producer: Bruce Young. -

Fascinating biography of a very private man somewhat bemused by his sudden fame as author of "Lord of the Flies". Extensive use is made of his journals and letters to produce a warts'n all bio. Golding comes to life as a not very appealing character but the insights into his creative writing process and analysis of his major novels makes you want to revisit them.

-

Carey's pacing has such a great sense of calm and he makes thoughtful connections in this dark but often hilarious bio. I cried twice; once when he met the queen, and again when he died. These may sound like cliché places to weep, but I'm telling you, now, at this moment, a week after reading, the images still haunt me.

-

So far I learned that Golding, from the picture on the cover, looks incredibly like my sort-of brother in law.

I never did get to the end of this book. I got about half way through and found it quite interesting, but then I decided I'd rather be reading Golding than a book about Golding. -

Although I haven't read any of Golding's I thoroughly enjoyed this biography. Its richness of detail is due to the fact that Carey had exclusive access to masses of diaries and manuscripts from which he made astute selections. Highly recommended.

-

This book is a good insigth into the complexity of the author of the lord of the flies.