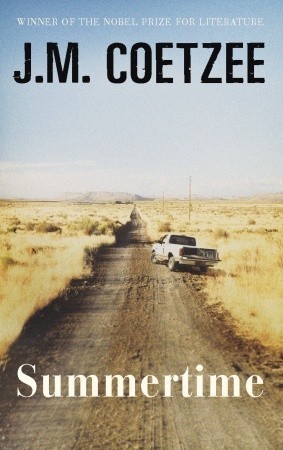

| Title | : | Summertime |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1846553180 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781846553189 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 266 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 2009 |

| Awards | : | Booker Prize (2009), New South Wales Premier's Literary Award Christina Stead Prize for Fiction (2010), Western Australian Premier's Book Award Fiction (2009), Prime Minister's Literary Awards Fiction (2010), Victorian Premier's Literary Award Vance Palmer Prize for Fiction (2010), Queensland Premier's Literary Award Fiction (2010), Dublin Literary Award (2011) |

A young English biographer is researching a book about the late South African writer John Coetzee, focusing on Coetzee in his thirties, at a time when he was living in a rundown cottage in the Cape Town suburbs with his widowed father - a time, the biographer is convinced, when Coetzee was finding himself as a writer. Never having met the man himself, the biographer interviews five people who knew Coetzee well, including a married woman with whom he had an affair, his cousin Margot, and a Brazilian dancer whose daughter took English lessons with him. These accounts add up to an image of an awkward, reserved, and bookish young man who finds it hard to make meaningful connections with the people around him.

Summertime Reviews

-

Summertime (Scenes from Provincial Life #3), J.M. Coetzee

Summertime is a 2009 novel by South African-born Nobel laureate J. M. Coetzee. It is the third in a series of fictionalized memoirs by Coetzee and details the life of one John Coetzee from the perspective of five people who have known him.

The novel largely takes place in the mid to late 1970's, largely in Cape Town, although there are also important scenes in more remote South African settings. While there are obvious similarities between the actual writer of the novel, J. M. Coetzee, and the subject of the novel, John Coetzee, there are some differences - most notably that the John Coetzee of the novel is reported as having died.

تاریخ نخستین خوانش: روز بیست و نهم ماه اکتبر سال2016میلادی

عنوان: تابستان زندگی - سه گانه صحنه هایی از زندگی شهرستان - کتاب سوم؛ ؛ نویسنده: جی.ام (جان مکسول) کوتسی؛ مترجم: نسرین طباطبایی؛ تهران، آینده درخشان، سال1393؛ در268ص؛ شابک9786005527643؛ موضوع: داستانهای نویسندگان افریقای جنوبی - سده21م

کتاب برنده نوبل ادبیات سال2003میلادی است؛ نوعی زندگینامه و نیز داستان خیال انگیز؛ برهه ای از زندگی «کوتسی» است، و گفتگو با چند تن که ایشان را نیک میشناختند؛ «جان مکسول کوتسی» در کتاب «تابستان زندگی» با نگاهی آفرینشگرانه به مرور یادمانها و تجربیاتشان پرداخته اند؛ ایشان صحنههایی را از زندگی شهرستانیها به تصویر کشیده اند؛ در این صحنههای تکرار ناشدنی، ایشان نگاهی انتقادی به زندگی شخصی خودشان دارند؛ افزون بر این، ایشان در این کتاب مبارزات اخلاقی دردناک را به تصویر کشیده اند؛ از معنای مراقبت یک انسان از انسانی دیگر حرف میزنند

نقل از متن: («خونهتون این دور و برهاست؟»؛ جواب دادم: «خونهم پایینتر از اینجاست، اون طرف کانستانشابرگ تو بیشهزار»؛ شوخی میکردم، از آن شوخیهایی که آن روزها بین سفیدپوستهای افریقای جنوبی رد و بدل میشد؛ تنها آدمهایی که در بیشهزار، بیشهزار واقعی، زندگی میکردند سیاهپوستها بودند؛ او از جوابم باید میفهمید که در یکی از آن ساختمانهای نوسازی که در بیشهزار آبا و اجدادی شبه جزیره «کیپ» ساخته شده بودند، زندگی میکنم؛ گفتم: «خُب، دیگه بیشتر از این مزاحم کارتون نمیشم؛ دارین چی میسازین؟»؛ گفت: «نمیسازم، فقط بتنکاری میکنم؛ اونقدر باهوش نیستم که ساختمون بسازم.»؛ این را شوخی کوچکی در جواب شوخی خودم تلقی کردم، چون اگر نه پولدار بود، نه خوشقیافه و نه جذاب ـ که هیچ کدام از اینها نبود ـ و علاوه بر آن باهوش هم نبود، دیگر چیزی باقی نمیماند؛ اما حتماً باهوش بود، حتی باهوش به نظر میرسید، آنطوری که دانشمندهایی که تمام عمر روی میکروسکپ قوز میکنند باهوش به نظر میرسند: نوعی هوشمندی محدود و کوتاهبینانه که با عینک دستهشاخی جور درمیآید؛ باور کنید به هیچوجه ـ اصلاً و ابداً ـ خیال نداشتم با این مرد سر به سر بگذارم ـ برای اینکه اصلاً جذاب نبود؛ انگار از سر تا پایش ماده ای خنثیساز پاشیده بودند، البته او با لوله کاغذ کادویی به قفسه سینه ام سقلمه زده بود، این را فراموش نکرده بودم و در حافظه سینه ام باقی مانده بود؛ اما حالا به خودم گفتم: «این احتمال که عمل آن روزش چیزی غیر از اتفاقی از روی بیدست و پایی، حرکت آدمی چلمن باشد ده به یک است.»؛ پس چرا تغییر عقیده دادم؟ چرا برگشتم؟ جواب دادن به این سئوال آسان نیست؛ اگر پدیده ای به این عنوان در کار باشد که مِهر کسی به دل دیگری بیفتد، مطمئن نیستم که در آن موقع مهر «جان» به دلم افتاده باشد؛ مدتها طول کشید تا مهرش به دلم نشست؛ دل بستن به او آسان نبود؛ موضعش نسبت به عالم و آدم محتاطانه تر و تدافعی تر از آن بود که آدم به او دل ببندد؛ گمان میکنم وقتی کوچک بود حتماً مادرش به او دل بسته بود، و دوستش داشت، چون کار مادرها همین است، اما مشکل میشد تصور کرد کس دیگری به او دل ببندد؛ اجازه میدهید چیزهایی را بیپرده بگویم؟ پس بگذارید تصویر را کامل کنم؛ در آن موقع بیست و ششساله بودم، و عشق را فقط با دو مرد تجربه کرده بودم: اولی پسری بود که در پانزده سالگی با او آشنا شدم، و تا وقتی که به خدمت وظیفه رفت، من و او سری از هم سوا داشتیم؛ وقتی رفت مدتی ماتم گرفتم و سرم توی لاک خودم بود، تا آنکه دوست پسر تازهای پیدا کردم؛ من و دوست پسر جدیدم در طول سالهای تحصیل یارهایی جدانشدنی بودیم، و به محض آنکه فارغ التحصیل شدیم با رضایت خانواده هامان ازدواج کردیم؛ در هر دو مورد قضیه برایم حد وسط نداشت؛ طبیعت من همیشه اینطور بود: حد وسط نداشتم؛ برای همین در بیست و ششسالگی از جهاتی خام و بیتجربه بودم، مثلاً هیچ نمیدانستم چطور میشود مردها را اغوا کرد.)؛ پایان نقل

تاریخ بهنگام رسانی 09/04/1400هجری خورشیدی؛ 24/01/1401هجری خورشیدیی؛ ا. شربیانی -

16 February 2020

HE WISHES he had written this book himself. What he doesn't quite understand is how Coetzee managed to turned a life so ordinary into something so extraordinary.

How much of it is indeed fiction? In writing such a book, will he have to detail his every transgression, or would he just make it up?

To be expanded on: why would a fictional indiscretion be so much more tolerable, when in a book like this and in the eyes of a reader there will be no distinction?. -

The halo effect perfected to exquisite levels in "Elizabeth Costello" is once again employed to similar effect here. But this time, the writer's own persona is the protagonist-non grata. What is left behind is what's compiled in this magnificent (but flawed) work--another dynamite narrative by another dynamite author, about racism in latter-20th century South Africa. In this instance, people (women, mostly) are interviewed, their experience with John Coetzee explored. These tales are tragicomic, gorgeous in their concise vernacular, realistic in their anecdotal detail, and above all very astute, very piercing. The halo effect, to me, means that we are afforded glimpses, albeit of a very "human" human being (J. Coetzee, reclusive, pained, but intuitive auteur, prefame) through vastly different modes-- the squeezing of juice from every possible clue makes this effort an endearing one, often transcending the very story it is telling. Which is what happens here.

Coetzee is the most CONSISTENT writer that I know of. This one is yet another one of his, to study, to truly, well, squeeze as much as one can from...

Also, as years progress, it is awesome to see the tragedy level becoming a wee-bit more intertwined with scenes of joy, or experiences of true love, by the evolving writer. Now, there is some awesome metalit element to his literature, as he, in the absurdly-titled "Summertime," is actually DEAD. Basically, this may be one of the longest faux-eulogies of all time. & one of the most unforgettable; even the pronouncement of "Fictions" as a subheading for "Summertime" is a lie: Instead of being short, various tales this novel, alas, is a pretty complete one. -

4.5★

Admittedly I haven’t read the first two books of this fictionalised biography (auto-biography?) of a young man growing up in South Africa,

Boyhood and

Youth. I also haven’t read

Disgrace, which won the Man Booker Prize in 1999 and sounds a lot like the story of the ‘late John Coetzee’ of this book – a professor leading a passionless life until he has an affair with a student (so says the blurb). The John of this book is also a Nobel Prize winner for literature, as is J.M.

Even without those books as background, this is an interesting device, letting us travel with a biographer who’s researching the ‘late’ Coetzee’s life by interviewing people from his past whom he apparently noted himself were important to him. The various voices are different enough that it reads like real interviews and real scrawled notes.

It is obvious to me, an armchair expert (yeah, right), that 'John' is a good example of a person with Asperger’s Syndrome. All Aspies are different, but being socially awkward is reasonably common, and everyone describes John that way, although there's certainly more to Asperger's and to John than that. It’s also important to remember that if J.M. is writing about himself, he certainly understands his effect on others and writes about it cringingly well.

The book is broken into sections, one for each interviewee, and we sense a thread running through the stories. They say he was an unremarkable man who held little real interest for them, and they’re not quite sure how they got involved with him in the first place or why he thinks they’re important. In fact, all are a little embarrassed about it.

The women have an air of Shakespeare’s “The lady doth protest too much methinks.” If he’s so dull, why do they keep saying things like "just one more story, and then I’m finished” ?

Julia is first. She noticed him shopping, and doesn’t he sound like a real catch?

“In appearance he was not what most people would call attractive. He was scrawny, he had a beard, he wore horn-rimmed glasses and sandals. He looked out of place, like a bird, one of those flightless birds; or like an abstracted scientist who had wandered by mistake out of his laboratory. There was an air of seediness about him too, an air of failure. I guessed there was no woman in his life, and it turned out I was right.”

She says she is always conscious of when a man is looking at her, but she never once felt that about him. She met him only when he picked up her dropped rolls of wrapping paper and disconcertingly (to her) pressed them into her breast as he returned them. This felt so intimate, that while she intended to avoid him, she stalked him, seduced him, and had an affair.

She still talks about him as if he’s dull, silly for wasting his life living with his ill father. But she keeps talking, and talking, and talking . . . about her husband, HIS affairs, her dissatisfaction, her bringing John into her household, her going to his ramshackle cottage and meeting his father. Julia does ramble on. He clearly made an impression, and she enjoyed the verbal sparring.

“He ran his life according to principles, whereas I was a pragmatist. Pragmatism always beats principles; that is just the way things are. The universe moves, the ground changes under our feet; principles are always a step behind. Principles are the stuff of comedy. Comedy is what you get when principles bump into reality. I know he had a reputation for being dour, but John Coetzee was actually quite funny. A figure of comedy. Dour comedy. Which, in an obscure way, he knew, even accepted. That is why I still look back on him with affection. If you want to know.”

And then she told him he ought to find a woman to look after him and get married.

Cousin Margot is next, and she is embarrassed both by him and for him. They were children together, but as adults, she is uncomfortable with him (like everyone else). When they are stranded overnight in a truck, a farmer rescues them in the morning, and she speaks Afrikaans with him. It’s second-nature for her,

“whereas the Afrikaans John speaks is stiff and bookish. Half of what John says probably goes over Hendrik’s head. ‘Which is more poetic, do you think, Hendrik: the rising sun or the setting sun? A goat or a sheep?’ ”

She reckons her family’s days are numbered since the Koup. The Coetzees are all lazy, slack, spineless, yet she’d had higher hopes for John and his bookish ways.

Her sister Carol finally spills the beans about John (some of which we know from earlier and some of which roughly matches J.M.’s history). She calls him “stuck-up”.

“He lives with his father, but only because he has no money. He is thirty-something years old with no prospects. He ran away from South Africa to escape the army. Then he was thrown out of America because he broke the law. Now he can’t find a proper job because he is too stuck-up. The two of them live on a the pathetic salary his father gets from the scrapyard where he works.”

When Margo asks John if he’s relieved to be back home after leaving America, he says

“But practically speaking, what future do I have in this country, where I have never fitted in? Perhaps a clean break would have been better after all. Cut yourself free of what you love and hope that the wound heals.”

The biographer interviews others, including one man, a colleague, who explains that they met and became friends when they applied for the same teaching position at the University of Cape Town. The biographer quotes from John’s own notes about himself and the interview, that he feels he's handled badly.

“He has taken the question too literally, responding too briefly. . . They want something more leisurely, more expansive . . . whether he would fit in in a provincial university that is doing its best to maintain standards in difficult time, to keep the flame of civilization burning.

In America, where they take job-hunting seriously, people like him, people who don’t know how to read the agenda behind a question, can’t speak in rounded paragraphs, don’t put themselves over with conviction—in short, people deficient in people skills – attend training sessions where they learn to look the interrogator in the eye, smile, respond to questions fully and with every appearance of sincerity. Presentation of the self: that is what they call it in America, without irony.”

It’s a rambling, piece-meal collection of what sound like reminiscences and notes and embarrassing anecdotes, but by the end, I actually had a clear picture of an interesting man who was trapped by circumstance and escaped into his intellect.

And if John is J.M., then I’m glad he moved to South Australia and became an Aussie. -

late at night, absent people or drink, when it rages out in furnace fear, i think of you and whether it be simply that misery loves company or even though we do die alone, you remind me that we all do it so at least we're all connected in our aloneness -- your life and your words in some tiny tiny tiny way lessen the burden of existence. as with my dog, i know that you will most likely die long before i do and it kind of makes me want to eat the shotgun knowing i'll be living in a world without jack and without coetzee, but if i did that my parents would be destroyed so i'd have to kill them first and if i killed my parents and then myself it'd really fuck up a whole bunch of people so i'd have to take out my sister and her husband and some others and it'd end up a real bloodbath and i couldn't very well do that.

rian malan said:

"A colleague who has worked with Coetzee for more than a decade claims to have seen him laugh just once. An acquaintance has attended several dinner parties where Coetzee has uttered not a single word."

i love you so much john maxwell coetzee and even though your post-elizabeth costello novels have been pretty weak they make me love you even more than your earlier masterpieces (too tired to explain myself). despite your cool and austere exterior i relate to you and feel as close to you as anyone i've never met; you turn me into an 11 yr old boy creaming his jeans over britney or gaga. you put before us a picture of human cruelty in a way no one else has and try to fashion out of your own life an impossibly gentle life, a life absent of all human cruelty. you are a miserable failure. you are ridiculous and sad and seem built to die alone. and i love you because of, not in spite of, your failures. -

I read this one because it was the shortest book I had left on the to-read shelf while waiting for the next part of my Booker longlist order to arrive. I was surprised by just how much I enjoyed it - I have read a lot of Coetzee and this is one of his wittiest, not least because his portrait of himself in the 70s refracted by an imaginary biographer and five interviewees is not a flattering one.

The five witnesses are bookended by two sets of notebook extracts (I am not sure whether these are real or fictional but suspect the latter). The interviewees are Julia, a married woman with whom the young writer has a brief affair, Margot, a cousin, Adriana, a Brazilian widow who is the mother of one of his pupils, Martin, a fellow university lecturer and Sophie, a French university colleague with who he has another affair. The first two are almost novella length, the rest are much shorter. The writer comes across as stubborn, driven and incapable of relating to the women he meets, and rather out of place in the conformist society of white South Africa. I suspect a degree of self-deprecating caricature, but that makes the book much more entertaining to read. -

Of all the three in series 'Scenes from a Provincial life', this was the one I had highest hopes from. Because this was the book that would relate to the period in his life when he was actually writing novels - and so, closer or in the period of his greatness. It was disappointing - because author actually increased the distance from his person by trying to see himself from point of view of other people.

The diary entries in the begining and the end might be truthful but the interviews in the middle seemed all made unless Coetzee had come up with an idea of time travel or inter-dimension travel, written as they are, as interviews of some of people once close to C. by a fictional biographer after C's death. Now this kind of thing presents more than one kind of issue. First, none of the people in general and women in particular interviews have been taken seemed to like Coetzee a lot. One wonders whether Coetzee isnt making their opinions of himself too critical (something common with first two instalments of this series too)

"Pragmatism always beats principles; that is just the way things are. The universe moves, the ground changes under our feet; principles are always a step behind. Principles are the stuff of comedy. Comedy is what you get when principles bump into reality. I know he had a reputation for being dour, but John Coetzee was actually quite funny. A figure of comedy. Dour comedy. Which, in an obscure way, he knew, even accepted. That is why I still look back on him."

Secondly, they probably won't be as honest to make the admissions even if Coetzee was to die. Thirdly, with most writers, it seems to me, the best part is their inner lives which is not available to observation of outsiders:

"And how fortunate that most people, even people who are no good at straight-out lying, are at least competent enough at concealment not to reveal what is going on inside them, not by the slightest tremor of the voice or dilation of the pupil!"

Coetzee seems to be labouring under the idea - common to so many idealist intellectuals (loners, more-or-less self created ones; as against university-created institutional intellectuals) that they do not belong to the world. That their inability to behave 'normally' (to imitate the social ways) make them unlikeable to others - which isn't always true or Coetzee wouldn't have ever become a famous author. It is a shame that he must so orignal a person should have so low an opinion of himself. It hardly seems to make him a very good autobiographer.

But that being said, he is still a very good writer with orignal ideas and ways of looking at the world and this shows up on this book too.

On convenience racism

"Breytenbach left the country years ago to live in Paris, and soon thereafter queered his pitch by marrying a Vietnamese woman,that is to say, a non-white, an Asiatic. He not only married her but, if one is to believe the poems in which she figures, is passionately in love with her. Despite which, says the Sunday Times, the Minister in his compassion will permit the couple a thirty-day visit during which the so-called Mrs Breytenbach will be treated as a white person, a temporary white, an honorary white."

Other Quotes

"No one is immortal. Books are not immortal. The entire globe on which we stand is going to be sucked into the sun and burnt to a cinder. After which the universe itself will implode and disappear down a black hole. Nothing is going to survive, not me, not you, and certainly not minority-interest books about imaginary frontiersmen in eighteenth-century South Africa."

"But to the barbarians, as Zbigniew Herbert has pointed out, irony is simply like salt: you crunch it between your teeth and enjoy a momentary savour; when the savour is gone, the brute facts are still there."

"Music isn't about fucking,' I went on. 'Music is about foreplay. It's about courtship. You sing to the maid -

It has been a very long time since I read something that original... The premise of the book is so unusually incisive, so creative in itself... Coetzee writes his own biography, post his fictive death, as strung together through his notebooks and the interviews of some of his contemporaries.

Behind the dry humor and subtle self-deprecation, there are some very serious underlying themes, mostly pertaining to life in South Africa in the 70's, Afrikaners, natives, Apartheid etc... but also dealing with elder parent care, teaching, and of course, writing as a pursuit and a process.

I am so impressed by this book! -

This s a work of imagination and art.

Here is a quote: "What if we are all fictionalizers!"’

I believe this to be true for all of us, whether we are cognizant of this or not.

The ideas presented in

Youth, the preceding book of this autobiographical but fictional series, are echoed here in

Summertime. Ironical humor is added. How the stories are put together and told are, however, quite different. We learn that Coetzee has died. A biography is to be written. It is based on interviews with five individuals. Also letters and fragments of notes left by Coetzee are used. What Coetzee is doing is telling of himself through others' impressions of him. What is said is far from complimentary. Coetzee seems in this way to be asking, "Who is this man, this man who has been me?" I like the approach very, very much. It is new. It is creative. It is not stale. It is his own groping search for the truth. Along the way we analyze and compare his and our own philosophy of life and views on literature, art and society.

The art of writing, cultural differences, politics, the influence of a person’s racial and familial heritage are central themes. How does Coetzee view his background as an Afrikaner—with shame or with pride? How we care for the elderly and the inadequacies of state run social services is another theme. On this topic, the book closes. It sent a shiver through my spine! To what extent are human beings able to care for one another? How and why and when do we let each other down?

Is the tone of the book dreary? NO! There is humor and the underlying, genuine search for a better understanding of human nature draws one’s attention!

There are five interviewees. They are very different from each other. Each is drawn with finesse. Each one becomes a character that feels so very real! I adored Adriana, a worried mother from Angola, a struggling immigrant residing in South Africa. Her daughter is tutored in English by Coetzee. She mistrusts him! The dialogue is superb. When she giggled, I smiled. She’s my favorite interviewee. She’s a dancer, attune to her body, her emotions, her soul. She senses Coetzee's emotional “woodenness”, his inability to sync with his feelings. The most important point is, however, that each interviewee is well drawn, each behaves and thinks and acts in congruence with their personality.

Coetzee felt as a sojourner. Home, where is that? Having lived in different countries, one loses a sense of where home is. I recognize this too!

The audiobook has six narrators. Each interviewee has a different narrator. The narrators are well chosen. They personify the characters. I wholeheartedly recommend listening to the audio version of this book. Five stars for the narration. The audiobook is extremely well produced.

************************

Fictional autobiographical trilogy:

*

Boyhood: Scenes from Provincial Life 4 stars

*

Youth 4 stars

*

Summertime 4 stars

*

Age of Iron 4 stars

*

Waiting for the Barbarians 5 stars

*

Disgrace 3 stars

*

The Master of Petersburg 3 stars -

As with many of my readings, I really liked the originality of the form in this book. Coetzee, Nobel Prize for Literature, totally renews the autobiographical genre by imagining a writer responsible for Coetzee's biography by interviewing all the people who knew him. It's not really modest, but it's effective. He allows himself the luxury of not showing himself to his advantage, a little cowardly, mediocre lover, with a downright dirty interior. Discourage academics with sharp pens by taking the lead? We are looking for the motivations, but it's a real good time to read.

-

Estamos ante la tercera parte de la autobiografía de Coetzee.

El primer libro es “Infancia” luego “Juventud” y llegamos a este tercer volumen que narra apenas 5 años de la vida del escritor. En está obra el autor se contempla a sí mismo en tercera persona, buscando distanciarse y ser objetivo. En el camino nos deleita con literatura de calidad, de la buena, de la que te hace pensar y disfrutar.

Es real lo que escribe? Sucedió lo que él narra? Es J.M Coetzee el hombre torpe, el inepto amante y antisocial que se describe? . Nadie tiene idea. Pero sin dudas es la mejor autobiografía falsa que podemos leer.

Sí podemos afirmar que por el costado está analizando la Sudáfrica sufrida del apartheid, el desarraigo de los habitantes que se sienten extranjeros en su propia tierra y una gran historia de padre-hijo.

Aplausos. -

“Troppo freddo, troppo pulito direi. Troppo facile. Troppa poca passione, passione creativa. Tutto qui”

Tempo d’estate conclude il ciclo dei romanzi biografici. Grandissima creazione letteraria: Coetzee è morto, un ipotetico biografo, Vincent, intervista cinque persone che sono state vicine allo scrittore: Julia, una amante; Margot, una cugina; Adriana, amore di Coetzee non ricambiato; Martin, un collega; Sophie, una collega con la quale ha avuto una relazione. E attraverso le parole di questo biografo che riporta le interviste a coloro che per un periodo hanno intrecciato le loro vite con quelle di C., Coetzee stesso scrive la propria biografia, cercando- o fingendo - di essere in questo modo il più obiettivo possibile. Emerge subito la tematica principale, al di là delle vicende quotidiane: la creazione letteraria riesce ad esprimere la realtà in modo fedele o in quanto opera letteraria ha vita propria? Ciò che è auspicabile è che il racconto, anche se non può essere vero alla lettera, lo sia nello spirito? Come possiamo fidarci del resoconto e delle interviste? Gli intervistati, interrogati su una persona di loro conoscenza, non potrebbero essere tutti “inventori di storie”? Non tende ognuno ad evidenziare cose che ad altri potrebbero essere sfuggite o che per altri potrebbero avere scarsa importanza? In ogni racconto c’è sempre troppo della persona che racconta e di quella che riporta. Gli intervistati, quando riascoltano le loro parole trascritte dal biografo, spesso non riconoscono la propria voce o i fatti raccontati, sembra loro quasi un’altra storia. Dando voce a cinque punti di vista differenti, C. vuole fornire una gamma di testimonianze indipendenti che partono da prospettive indipendenti. Ma è proprio qui la finzione letteraria. Non esiste alcun biografo, e forse non esistono neppure le persone intervistate (non so se siano state presenze reali nella vita di C. o se le abbia create di sana pianta), a parlare è Coetzee stesso, sempre Coetzee, che con vera spietatezza e consapevolezza si rivela al lettore, anche nelle sue pieghe più intime. Non teme il giudizio del lettore, mette in costante dubbio il proprio valore non solo come artista, ma come uomo. Fa dire ad Adriana : “Signor Vincent, ai suoi occhi John Coetzee è un grande scrittore e un eroe, io lo accetto… Per me, invece – mi perdoni se glielo dico, ma è morto e quindi non posso ferire i suoi sentimenti – per me non è nulla… soltanto un motivo di irritazione, di imbarazzo. Non era nulla e le sue parole non erano nulla… per me era davvero uno stupido. Quanto alle sue lettere, scrivere lettere ad una donna non dimostra che la si ami. Quest’uomo non era innamorato di me, era innamorato di una qualche idea di me, di qualche fantasia di un’amante latina che si era creato nella mente. Vorrei che al posto mio avesse trovato un’altra scrittrice, un’altra persona fantasiosa di cui innamorarsi. Avrebbero potuto essere felici a fare l’amore tutto il giorno con le loro idee l’uno dell’altro”. Ancora la dicotomia tra arte e vita, artista e uomo, accomunate dal comune atteggiamento di C. nei loro confronti, quel distacco indicato dalla citazione nel titolo di queste righe. E ancora: "...ma era davvero un grande scrittore? Perché, per come la penso io, il talento per le parole non basta se si vuole diventare un grande scrittore. Bisogna essere anche un grande uomo. Lui era un uomo piccolo, un uomo privo di importanza." Però, dico io, sarà anche stato piccolo come uomo, ma come artista ha vinto il Nobel. Che sia possibile, quindi, separare vita e arte? E poi, nell’intervista a Martin - altra presenza maschile insieme al biografo e al fantasma di Coetzee – si svela il fulcro sia della vita di uomo che di artista: “…io e lui condividevamo la stessa posizione sul Sudafrica, cioè sulla nostra presenza in quel paese. Era illegittima. Magari avevamo un diritto astratto di starci, un diritto di nascita, ma su basi fraudolente. La nostra esistenza si fondava su un crimine, precisamente la conquista coloniale, perpetuato dall’apartheid. Ci sentivamo proprio il contrario dei nativi, degli indigeni. Visitatori, residenti temporanei e in questo senso senza casa, senza patria”. Da qui la fuga, il ritorno, e la nuova partenza. Coetzee vive ancora, vegeto, in Australia, con relativa cittadinanza. Forse unico esemplare di uomo freddo che mi abbia in qualche modo interessato. -

Un libro molto bello, forse il suo più bello. Coetzee immagina che alla sua morte un ricercatore intenzionato a scrivere un libro su di lui vada ad intervistare le donne che lo hanno conosciuto quando aveva circa trent'anni e viveva a Città del Capo. Ne scaturisce il ritratto vagamente comico di un uomo timoroso, senza talento, impacciato nelle relazioni con le donne (uno che voleva fare l'amore armonizzando i movimenti con la musica di Schubert e le donne lo guardavano come si guarda un pazzo). Coetzee non sta dicendo che quella non è la verità o che è soltanto un punto di vista di alcune persone che lo hanno conosciuto parzialmente. Sta dicendo che non ci si conosce come ci si aspetta. Ci si conosce incidentalmente, nelle fratture comuni. Fuori tempo. Ci sono esperienze che non capiteranno e se non capitano non potranno rivelare parti di noi che restano nascoste o mai nate. Non possiamo dire "io ero quello che ero se fosse capitato questo o quello". E le parole per raccontare non basta dire che siano inesatte o mancanti, sono sempre un'altra realtà. Complicano talvolta le cose. Per Wittgenstein quando ci si trova sul ghiaccio bisogna rigenerare l'attrito con i fatti. Bisogna provocare le cose quando non accadono, ma anche questo indurre le cose non basta a conoscerci, a comunicare, a manifestare un io raggiera. Molti affermano che col corpo si capisce. Col corpo si sente, si gode, ci si sfama, si sospendono le cose. Si fa metafisica.

-

Finalizo con

Verano la lectura de la trilogía de novelas ¿autobiográficas? de J.M. Coetzee, que incluye también

Infancia y

Juventud. Y esta es, de las tres, las que más me ha gustado. Voy a tratar de explicar por qué:

Si en las reseñas de las otras dos novelas indicaba que un rasgo interesante de su estilo era que, aun tratándose de novelas autobiográficas, el autor había elegido un narrador en tercera persona en lugar de hacerlo en primera persona, seguramente para distanciarse emocionalmente de su propia narración, en esta tercera Coetzee da una vuelta de tuerca. Aquí aparece un biógrafo ficticio, un tal Mr. Vincent, quien, tras la muerte del escritor, entrevista a personas que conocieron a John Coetzee para escribir una biografía de los años que transcurrieron desde su regreso a Sudáfrica en 1972 (tras ser al parecer expulsado de Estados Unidos por su participación en manifestaciones contra la guerra de Vietnam) y la consecución de sus primeros éxitos literarios, hacia 1977. Una época en la que John Coetzee vive con su padre, a quien se ve obligado a cuidar tras el fallecimiento de su madre. Una tarea que no parece ejercer con gusto:“Los chicos quieren a sus madres, no a sus padres. ¿No ha leído a Freud? Los chicos odian a su padre y quieren suplantarlo en el afecto de su madre. No, claro que John no quería a su padre, no quería a nadie, no estaba hecho para amar. Pero tenía un sentimiento de culpa con respecto a su padre. Se sentía culpable У, en consecuencia, cumplía con su deber” (De la entrevista a Julia)

Viven en una casita miserable llena de humedades en un suburbio de Ciudad del Cabo:“El cuarto de baño era primitivo, la taza del lavabo no estaba limpia. Un olor desagradable a sudor masculino y toallas húmedas flotaba en el aire. No tenía idea de adonde había ido John ni de cuándo volvería. Me hice café y exploré un poco. De una habitación a otra, los techos eran tan bajos que temía asfixiarme. No era más que una casa de campo, eso lo comprendía, pero ¿por qué la habían construido para enanos?

Me asomé a la habitación de Coetzee padre. Había dejado la luz encendida, la luz mortecina de una sola bombilla sin pantalla en el centro del techo. Sobre una mesa, al lado de la cama, un periódico doblado… “ (De la entrevista a Julia)

Es en esa interesante estructura narrativa donde radica, a mi juicio, una de las virtudes de la obra. Porque el lector podría preguntarse: ¿estamos ante una novela autobiográfica o se trata de una autobiografía novelada? Y yo añadiría, ¿y si, en realidad, no sé trata ni de lo uno ni de lo otro, sino que tenemos ante nosotros una novela sobre un tal John Coetzee que, casualmente, es homónimo del autor? ¿Una novela que el autor usa para hablarnos de los temas recurrentes en sus obras, pero vistiéndolo como una “autobiografía ficticia”?

El presunto biógrafo se entrevista con cinco personas (¿reales, ficticias también?) que trataron o conocieron a John Coetzee en vida: Julia, una mujer infelizmente casada con la que John mantiene una relación breve y tortuosa; su prima Margot, de la que se enamoró a los seis años, y que es el único lazo familiar que trata de comprenderlo sin conseguirlo; Adriana, una profesora brasileña de baile a cuya hija adolescente John da clases de refuerzo de inglés en un colegio católico, y que se siente acosada por él al tiempo que piensa que John juega con los sentimientos de su hija; Martin, un amigo y colega en la universidad; y Sophie, una mujer francesa compañera de trabajo en la universidad, con la que tiene otro affaire. He disfrutado especialmente las entrevistas con Julia, Margot y Adriana, en las que se habla mucho más de ellas que de John, que no es más que un personaje que aparece en algún momento de sus vidas sin dejar la huella que, al parecer, ellas dejaron en él”.“Porque John Coetzee no era mi príncipe. Por fin llego a lo esencial. Si ésa era la pregunta en el fondo de su mente cuando llegó a Wilmington («¿Va a ser esta otra de esas mujeres que confundió a John Coetzee con su príncipe secreto?»), ahora tiene la respuesta. John no era mi príncipe. Y no sólo eso: si me ha escuchado con atención, a estas alturas podrá ver lo improbable que era que pudiera haber sido un príncipe, un príncipe satisfactorio, para cualquier doncella del mundo.

¿No está de acuerdo? ¿Opina de otra manera? ¿Cree que era yo, no él, quien tenía la culpa... el defecto, la deficiencia? Bien, eche un vistazo a los libros que escribió.

¿Cuál es el tema recurrente en un libro tras otro? El de que la mujer no se enamora del hombre. Puede que el hombre ame o no ame a la mujer, pero ésta nunca ama al hombre. ¿Qué cree usted que refleja ese tema? Mi conjetura, una conjetura muy bien fundamentada, es que refleja la experiencia de su vida. Las mujeres no se enamoraban de él... por lo menos las mujeres que estaban en su sano juicio. Lo inspeccionaban, lo husmeaban, tal vez incluso lo probaban. Y entonces seguían su camino. Seguían su camino como hice yo…” (De la entrevista a Julia)

Y es precisamente en esas entrevistas y, sobre todo, en las de las mujeres, donde Coetzee aprovecha para hablarnos de esos temas recurrentes en sus obras a los que aludía antes: la soledad, la alienación, la monotonía de la existencia humana, la violencia implícita o explícita, el racismo o el apartheid.“Un día, cuando llegué a mi banco, había una mujer allí sentada, con su bebé al lado. En la mayor parte de los lugares, los jardines públicos, los andenes de las estaciones, etcétera, los bancos estaban marcados: «Blancos» o «No blancos»; sin embargo, aquél no lo estaba. Le dije a la mujer «Qué criatura tan linda» o algo por el estilo, con la intención de ser amigable. Ella me miró con una expresión asustada. «Dankie, mies», susurró, que significa «Gracias, señorita», tomó su bebé en brazos y se marchó. «No soy una de ellos», quise gritarle. Pero, naturalmente, no lo hice.” (De la entrevista con Adriana, la profesora de baile brasileña que se sintió acosada por John)

Ninguna de esas mujeres, ni siquiera su prima, tiene una gran opinión de John.“…que era tan bobo, estaba tan separado de la realidad, que no podía distinguir entre tocar a una mujer como si fuese un instrumento musical y amar a una mujer. Un hombre que amaba de manera mecánica. ¡Una no sabe si reír o llorar!

Por eso nunca fue mi príncipe azul. Por eso nunca le dejé que se me llevara en su caballo blanco. Porque no era un príncipe, sino una rana. Porque no era humano, no lo era del todo. (De la entrevista a Julia)

Al contrario, lo consideran un hombre incapaz de mantener una relación afectiva con una mujer, demasiado frío, inseguro, desnortado: un slapgat, término despectivo en afrikáans que puede traducirse al español como "culo flojo”.”¿Qué había esperado ella de su primo?

Que redimiera a los hombres de la familia Coetzee.

¿Por qué quería la redención de los hombres de la familia Coetzee?

Porque todos ellos son tan slapgat.

¿Por qué había depositado sus esperanzas concretamente en John?

Porque, entre los hombres de la familia Coetzee, él era el único bendecido con la mejor oportunidad. Estaba bendecido con la oportunidad y no la aprovechaba.” (De la entrevista a su prima Margot)”No, no tuve, por emplear la palabra que usted ha dicho, «relaciones» con el señor Coetzee. Le diré más. Para mí no era natural sentir algo por un hombre como él, un hombre que era tan blando. Sí, blando”. (De la entrevista con Adriana, la profesora de baile brasileña que se sintió acosada por John)

De alguna forma se repite lo que ya advertíamos en las otras dos novelas, la de incidir en los aspectos más negativos de su personalidad.” —¡Esto no es un juego amoroso! -le dije entre dientes-. ¿No ves que te detesto?

Déjame en paz y deja a mi hija en paz, o te denunciaré a la escuela! Era cierto: si no hubiera estado llenando la cabeza de mi hija con peligrosas tonterías, nunca le habría invitado a nuestro piso, y la lamentable persecución a que me sometía nunca habría empezado.”.

…

“Mire, señor Vincent, para usted John Coetzee es un gran escritor y un héroe, eso lo acepto, ¿por qué si no estaría aquí, por qué si no escribiría este libro? Para mí, en cambio, y perdóneme que diga esto, pero está muerto, por lo que no puedo herir sus sentimientos, para mí no es nada. No es nada y no fue nada, tan sólo una irritación, algo embarazoso. No era nada y sus palabras no eran nada. Comprendo que se enfade porque hago que parezca un necio.Sin embargo, para mí realmente era un necio. En cuanto a sus cartas, escribirle cartas a una muier no demuestra que la ames”.

…

“El amor: ¿cómo puedes ser un gran escritor cuando no sabes nada del amor? ¿Cree usted que puedo ser mujer y no saber en lo más hondo de mi ser qué clase de amante es un hombre? Créame, me estremezco al pensar en cómo debían de ser las relaciones íntimas con un hombre así. No sé si llegó a casarse, pero si lo hizo me estremezco por la mujer que se casó con él.”

…

“Además, permítame confesarle que siento curiosidad por lo que le han contado las demás mujeres que hubo en la vida de ese hombre, si también a ellas les pareció que aquel amante suyo estaba hecho de madera. Porque, ¿sabe?, creo que ése es el título que debería poner a su libro: El hombre de madera”. (De la entrevista con Adriana, la profesora de baile brasileña que se sintió acosada por John)

Pero, ¿hay que creer todo lo que de él dicen los entrevistados o es simplemente lo que Coetzee quiere que creamos? La clave, a mi juicio, la da el propio autor poniendo en boca de Vincent, el falso biógrafo, esta frase referida a sus cuadernos y diarios, cuando una de las entrevistadas, Sophie, le cuestiona que se centre tanto en las entrevistas para preparar la biografía en lugar de acudir a los diarios y los cuadernos de John :“…he examinado los diarios y las cartas, señora Denöel. No es posible confiar en lo que Coetzee escribe en ellos, no como un registro exacto de los hechos, y no porque fuese un embustero, sino porque era un creador de ficciones. En las cartas crea una ficción de sí mismo para sus corresponsales; en los diarios hace algo muy similar para sí mismo, o tal vez para la posteridad. Como documentos son valiosos, desde luego, pero si quiere usted saber la verdad tendrá que buscarla detrás de las ficciones que elaboran y oírla de quienes le conocieron personalmente.”

Y en sus novelas pretendidamente autobiográficas hace lo mismo, añadiría yo.

He disfrutado mucho con la novela. La estructura narrativa, con la utilización de cinco puntos de vista distintos (los entrevistados) y el recurso de echar mano de un entrevistador que prepara una biografía de un autor ya fallecido me parece brillante. Se podría achacar que ninguno de los entrevistados aporta demasiada información sobre John, aparte de su carácter frío de “culo flojo”. Sin embargo, creo que la intención de Coetzee no es darnos información sobre sí mismo, sino que se vale de una supuesta autobiografía para seguir hablándonos de sus temas favoritos, esos temas recurrentes en todas sus novelas.

Recomendaría

Verano a aquellos lectores que disfrutan de la literatura reflexiva y contemplativa, y que estén interesados en la exploración de temas complejos relacionados con la identidad, la creatividad y la sociedad sudafricana. También recomendaría esta novela a los lectores que disfrutan de la ficción metaficcional, que explora las tensiones entre la vida y la ficción, o a aquellos interesados en la historia y la política de Sudáfrica. -

What an odd book. The author writes it as though he is someone else writing his biography after his death. Parts of it were very strange and parts of it were hard to understand. As someone who was living in South Africa in the late 70's I really enjoyed the African references and being able to practice the little Afrikaans I still remember. Apart from that though I guess I was not really enamoured of the book although I feel encouraged to maybe try another of his books in the near future.

-

Apparently this is the third of a type of trilogy. I did not know that. I bought it because it was short. Sorry, John. I was on vacation at the beach. It was called Summertime. It was available in paperback and I was low on cash. What I got when I began to read was infinitely more. There are some books that affect us so deeply the $15.00 price seems ludicrous.

Admittedly, I am a lousy fan. There are few authors whose complete works I’ve read, no matter how much I admire their writing. Fewer still about whom I know anything personal. Summertime is a fictionalized biography. Interviews for a biography and notes written by the subject himself, really; an unfinished work. This furthers the impression of looking in on a life – the naturalness of it, the side of biographies we don’t normally see. It’s an engaging portrait of a man, a writer, an artist, possibly even Coetzee himself. All those things. It’s wise and beautiful and wry and, if not a strictly factual account of his life, perhaps it gives a truer glimpse of him. For what great writer writes anything without showing us something of themselves?

One of the things I do know about him is his famed evasiveness. He seems disturbed by the rockstar writer phenomenon and plays with that here. The biographer interviews the women that have most impacted the great author’s life. What indelible mark did he leave on their own? Disappointment. He was only a man. A man who was more alive within himself, than out. He couldn’t dance. To express himself without words – lots and lots of words – was nearly impossible. Yet he rarely spoke. The painful awkwardness of being human is captured perfectly as he seems to slyly poke fun at both himself and the rest of us. The women are repeatedly referred to as “his conquests” or “his women”, but it’s clear in each case that it’s him who has been conquered. As they speak of their relations with him, detailing his failings, they reveal more of themselves and their own shortcomings. That’s not to say they’re unlikable. More real. They’re strong, self-determined women, both touched and frustrated by this man. He speaks a different language, figuratively. And so he can be no more to them than South Africa in flux – transitory, impermanent. Disappointment. They move on. The one constant, from beginning to end, is his father. Always in his mind, his memory, the reality of caring for him… always a silent presence in his relationships with women. For that reason the story feels like an apology. To the women who never knew how much they meant to him. And to his father, for trying to live while he is dying. -

After Boyhood and Youth, I expected another searing self-portrait told in calm and beautifully measured third-person. What I got is autobiography in quite a revolutionary form: the women who knew Coetzee in his early thirties are interviewed about the now-dead author. Utterly engaging, filled with awkward intimacy and painful slip-ups, Summertime is the best book in the trilogy, the best book I've read in a year.

Another interesting aspect of the book: so many "greats" have written their portraits of the artists as young men -- Goethe, Flaubert, Joyce, and Coetzee himself spring to mind. But I've never read a self-examination focusing on this point -- beyond youth, "young-manhood", I suppose -- the trials by fire after self-awareness has cemented and the moral compass has been set, but before artistic recognition occurs. -

St Peter's and St Paul's Parish Church, Lavenham, book sale

Here is Coetzee writing as if Coetzee is dead and now Vincent is asking around to find out about people's feelings about the dead man.

Height of self-indulgent conceit? Well yes, only this is fiction and there is a lot revealed about South Africa in the 70s.

Sound confusing? It isn't, really not. I did take breathers in between the sections to mull over the underlying story of a country and attitude in change.

4* Waiting for the Barbarians

1* Foe

WL Dusklands

3* Summertime -

"He examinado los diarios y las cartas, señora Denoël. No es posible confiar en lo que Coetzee escribe en ellos, no como un registro exacto de los hechos, y no porque fuese un embustero, sino porque era un creador de ficciones. En las cartas crea una ficción de sí mismo para sus corresponsales; en los diarios hace algo muy similar para sí mismo, o tal vez para la posteridad. Como documentos son valiosos, desde luego, pero si quiere usted saber la verdad tendrá que buscarla detrás de las ficciones que elaboran y oírla de quienes le conocieron personalmente"

Magnífica.

Difícil escoger mejor la última lectura del año. Por varias razones.

A desarrollar: qué razones son. Por qué la lectura sobre el Karoo (la meseta semidesértica de Sudáfrica) mientras observa la puesta de sol en Cádiz es tan representativa, o tan simbólica. A explorar: los límites de la ficción y la autoficción. Qué podemos saber y qué no. Pregunta: ¿qué es lo que nos mueve realmente? ¿quienes somos? ¿qué nos emociona. -

Novelists enjoy taking revenge on biographers. A typical example of this phenomenon is William Golding’s The Paper Men (1984), in which a biographer is featured as a snoop digging through his subject’s kitchen pail. Only in rare instances do biographers not come off as second-raters and sensationalists, as in Bernard Malamud’s Dubin’s Lives (1979). But no writer of distinction has definitively challenged the line Henry James laid down in The Aspern Papers (1888), where the biographer is dismissed as a “publishing scoundrel.” Thus J. M. Coetzee’s Summertime is quite a surprise.

Rather than focusing on the unseemly prying biographer—a young Englishman named only as Vincent, about whom we learn very little—the subject, Coetzee himself (or rather his fictional persona, since the Coetzee of the novel is deceased) draws most of the fire. The biographer’s interviewees, who represent quite a range of ages, nationalities, genders, and occupations, come to remarkably similar conclusions about Coetzee: He was not much of a lover and did not demonstrate the genius that would be expected of a Nobel Prize winner. “Women didn’t fall for him,” reports Dr. Julia Frankl, who had an affair with the writer. His cousin Margot Jonker wonders what happened to the brilliant boy she once loved and why he has become a drifter living with his father. To Adrianna Nascimento, a Brazilian woman who spurned Coetzee’s advances, he is a fool and hardly a man at all. But wait! It gets worse: Sophie Denoël, one of Coetzee’s colleagues who taught a course with him, concludes he is an overrated writer devoid of originality.

The interviews make powerful, compelling reading because the voices are so distinctive. The biographer rarely interjects himself. He asks questions and occasionally responds to his interviewee’s queries, fending off their hostile comments about biographers as gossip-mongers by blandly announcing that they can excise whatever they deem inappropriate from his narrative. The only male interviewee, Martin, is concerned that Vincent’s interest in Coetzee’s personal life will come “at the expense of the man’s actual achievement as a writer.” But this objection is raised perfunctorily and does not merit the attention some reviewers give it as an example of the novel’s supposedly anti-biographical theme.

Quite often the biographer maintains silence in the face of provocative comments calling his integrity into question. He is there to get the story and remains thoroughly professional. As a result, so much of the palaver about the indiscretions of biographers seems petty—especially compared to this engrossing investigation of how friends, family, and lovers assess the man they knew. They are far harder on him than any biographer could possibly be.

Coetzee has used himself—or should we say a simulacrum of himself—to show that biography has a powerful a story to tell, regardless of who is hurt and whose privacy is violated. Coetzee seems an anomaly among modern authors, many of whom put their energies into thwarting biographers and trashing the genre. In contrast, Coetzee addresses the profound human need biography satisfies. It is as if he said to himself, “I cannot control what others have thought of me. In fact, there is a pattern of such reactions that some biographer is bound to shape into a narrative. So why not take a whack at it myself?”

For Coetzee, the biographer is not the issue. In Summertime, we do not even learn Vincent’s full name, let alone the experiences that led him to pick his subject— his motivations are not the point. On the contrary, Coetzee seems to realize that he has drawn the world to himself, and the world will find him out. A biography is not something he owes the public; it is just inevitable, no matter what he does and no matter what kind of life he has fashioned.

In so far as the biographer does present a brief for his work, it is mainly this idea that Coetzee belongs to the world and no permission or authorization is required to write Coetzee’s life. The biographer tells this to one of his wary informants, but at the same time he acknowledges that each of his interviewees knew Coetzee in a particular way and that he wants to preserve their memories. At first, it may seem that Vincent is ceding too much when he agrees to omit certain stories, but the overall pattern of the testimony is so persuasive that eliminating this or that iteration of it hardly matters.

Is this novel a disguised autobiography? The question seems to be dismissed in Summertime when Vincent remarks that Coetzee was a “fictioneer”: “In his letters he is making up a fiction of himself for his correspondents; in his diaries he is doing much the same for his own eyes, or perhaps for posterity.” Such comments level the playing field on which biography and autobiography are the contestants. In effect, there is no unimpeachable standard of truth by which a biography can be found wanting. Thus the extracts from the fictive Coetzee’s notebooks do nothing to undermine the biographer’s work.

Summertime is that rare novel that grants biography its autonomy and treats the biographer as an independent agent, not a parasite or a hanger-on to someone else’s life. It is also a work of fiction that perhaps will break the mold Henry James cast for biography, one that has bedeviled its practitioners for more than a century. -

Coetzee's Scenes from a Provincial Life is turning into one of the weirdest memoir projects ever. Apart from his decision to mix fiction with fact, and the obvious confusion over what is true and what isn't, there is also the public-humiliation aspect of these books. Coetzee really knows how to take himself down a peg: in this latest installment he can't fix a car, can't dance, can't cook, is a poor lover (and, worse, a strange one), has a messy house, a bad haircut, and persists in a teaching career for which he has no special gift. It even rains on his picnic, literally rains on it. All those things that turn you off a person are embodied in John Coetzee. As one woman puts it, he isn't like a real man; he's like one of those priests who seems a perpetual boy, and then one day you find he's suddenly become old. Somehow this wretch managed to pick up a Nobel Prize.

With another writer I might get infuriated with this approach: underneath the masochism, it suggests a control freak who anticipates every criticism--who who wants to tear himself down before anyone else does: "Look, I'll show you how to do it." But I know Coetzee to be a compassionate, empathetic writer; this portrait of a cold fish cannot be the whole truth. So what's going on here?

While many of the elements here are completely made up, a certain residue is left over that, I have no doubt, reflects the reality. This was true of the earlier volumes as well. The shape and taste of the life is there, even if the facts are all wrong. We're left suspecting that the artist, who is heroic, has lived deep inside himself--a sentient iceberg that, all these years later, is still worried over the disappointment and confusion he feels he has caused. Coetzee relieves the memoir of all its boring facts, just as he relieves the novel of all its tiresome artifice, to create the only possible answer for his solitude. -

I normally write a review the day after I've finished a book, long enough to coalesce my thoughts, short enough for it not to feel nagging. Because I read this for a group read and felt so lukewarm (is that an oxymoron?) about it, I put off the review, hoping I would get more out of the book after the discussion. That didn't happen.

I don't usually say 'how' I wish a book to be, as I don't usually think it's my place as reader to do so; but I can't help feeling with this one that I wish Coetzee had been just a touch less evasive. The notebooks, interviews, undated fragments -- they all add up to too much distancing, especially for what should be such an intimate topic.

I wasn't bored while reading the book: it's well-written after all (though when I went back to reread it, thinking I might see what others had seen, I couldn't get past the first section), but I kept thinking it was going somewhere and then it wouldn't. I'm sure that was intentional, but I didn't find that it made for great literature, unlike, say,

Disgrace. Even though

Disgrace arguably has a Coetzee persona as its narratorial voice too, I think its main character stands on its own, unlike the John of this book. -

«Καθηλωτικό, αστείο, συγκινητικό, γεμάτο ζωή» είναι το σχόλιο του Observer που φιγουράρει στο εξώφυλλο. Κι εγώ έκλαιγα. Ποτάμι -όχι του Θεοδωράκη- τα δάκρυα. Από το ασταμάτητο χασμουρητό. Φιλάρεσκο μυθιστόρημα: ένας συγγραφέας, που δεν βλέπει πέρα από τη μύτη του, γράφει ένα μυθιστόρημα για έναν τύπο που γράφει τη βιογραφία του νεκρού πλέον συγγραφέως. Δηλαδή, για να μη φαίνεται ότι περιαυτολογεί, εφευρίσκει έναν τύπο να μιλάει για τον Κουτσί όπως θα μίλαγε ο Κουτσί αν ήθελε και καλά να κάνει σκληρή αυτοκριτική, τέτοια που να εντυπωσιάσει τους τρίτους με την άνεσή της. Δεν έχω διαβάσει πιο επίπεδο, άνευρο, άοσμο, άχρωμο μυθιστόρημα στη ζωή μου. Για να καταλάβεις, από τη μέση και μετά άρχισα να διαβάζω τα κεφάλαια από το τέλος στην αρχή και, ναι, πράγματι, έτσι απέκτησε ένα κάποιο ενδιαφέρον. Ισως θα έπρεπε να το διαβάσω εξ ολοκλήρου από το τέλος στην αρχή για να με αρέσει.

(με τη διαρκή υποσημείωση, που ισχύει για όλα τα βιβλία, ότι στην αποτυχημένη σχέση μεταξύ αναγνώστη - συγγραφέα δεν φταίει πάντα ο συγγραφέας αλλά μπορεί να φταίει και ο αναγνώστης -δηλ. μπορεί εγώ να μην κατάλαβα τίποτε από το Θέρος ή μπορεί να ήμουν σε κατάλληλη διάθεση για να το διαβάσω.) -

This novel started off with a lot of promise, but as it progressed the story disintegrated and became very piecemeal and lacking as a complete narrative.

The premise of telling the biography of the fictional(?) novelist John Coetzee from different perspective was an interesting one, but from my perspective was in the end unsuccessful and confusing, in particular the section told from Adriana's perspective.

I'm still not sure hpw much of the novel is fiction or fact, perhaps this is the feeling that you are supposed to be left with, I don't know.

Overall a bit of a disappointing read. -

Postales sobre un escritor muerto (Enumeración, 2020)

1. Muerto el autor, un biógrafo imaginario entrevista sobre su vida. La honestidad del entrevistador es presentar tal cual las respuestas imaginadas. La mirada de los otros construye al autor.

2. No hay compasión en la mirada ajena, en especial porque es la mirada del amor, o de algo parecido a la amistad. Inclementes las amantes revelan al hombre, pequeño, normal, que gana un nobel.

3. Poco concede de importancia a la obra. Aquí es la anécdota humillante, humilde, la que revela a alguien en voz de quienes no le admiraron enceguecidos por su obra. Que le leyeron, acaso, con el cariño distante de quienes nos ven caer.

4. El autor trabaja con las manos, necesita limpiarse la culpa de ser un explotador, de pertenecer al bando de los colonizadores. Espera con barro lavar la sangre derramada en los procesos de conquista.

5. El autor se hace vegetariano, necesita sentir que su existencia no está alimentando la crueldad del mundo. Persigue la santidad como la última esperanza de redención, quizás así pueda vencer su soledad.

6. El autor vive solo con su padre. La madre ha muerto. El autor no la vio morir. No estuvo. No aguantó su mano. Nunca pudo resolver lo que quedará ahora para siempre sin resolver del todo.

7. La inmensidad de la llanura sin horizonte sigue siendo el conjuro primigenio, la esperanza, la fortuna. En una escena, una camioneta varada en mitad de un camino solitario podría haber sido barca. No lo fue.

8. Sigue la falta de empeño, de fuerza, de determinación. Esta debilidad crónica parece revestir otra forma de fortaleza. Esta apatía reiterada es una manera de encarar el mundo con el deseo de ser un matorral.

9. Escribir o no escribir. Cuidar o no cuidar de su padre. En las encrucijadas elegir no elegir y que entonces lo inevitable se manifieste y sea todo, entonces, como si no pudiera ser de otra manera.

10. El autor muere. Inventa otro yo que lo narre. Sólo ahí consigue fuerza. De los tres libros este es el mejor. -

Được kể qua 5 nhân vật, 3 cô nhân tình, 1 đồng nghiệp và 1 người chị họ để từ đó chân dung J.M. Coetzee hiện ra rõ nét hơn. Cuốn này nói nhiều hơn về chính trị, về khoảng thời gian ông đưa mình vào phản đối chiến tranh Việt Nam rồi bị trục xuất từ Mỹ về lại Nam Phi.

Cuốn này khác hẳn 2 cuốn trước, chủ yếu từ ngôi thứ 3 quan sát thông qua các cuộc phỏng vấn. Coetzee đi 1 vòng lớn để tiến tới giải thích những gì đã xảy ra trong ông: về những cuộc tình, về nhận thức lỡ làng hay chính cả những nhận định về các cuốn sách sau này. Điều khá thú vị là ông tự nhận xét những cuốn sách của mình, mượn vai các nhân vật, để chê trách về việc các chủ đề sáo mòn lặp đi lặp lại. Có thể ông hiểu nhưng không làm gì khác được.

Một bộ ba vô tiền khoáng hậu. -

Summertime by J.M. Coetzee is labeled "fiction," not "a novel," or "a collection of autobiographical investigations disguised as a story cycle," or some other generic propositon. Just "fiction."

Ok, it goes this way: there is a biographer, an academic, who goes through the deceased John Coetzee's notebooks and focuses a lot of effort on five extended interviews with four women and one man who were important in Coetzee's life. Two of the women were sexually involved with him; one was a cousin; one did everything she could not to accept his advances. The man is presented as a literary friend, an academic.

Spun out at novel-length, this manuscript effectively uses the apparent nonentity of John Coetzee as he saw (sees) himself in the form of a blank canvas upon which the five interviewees can talk about themselves. We learn more about them than him. About him we learn he's resevered or shy, well but generally educated, something of a utopian, something of a romantic, a dutiful son who dislikes being a dutiful son when his father's health begins to break down…and so on.

About the interviewees we learn that they managed to live without receiving a great deal from the likes of John Coetzee. We hear about their affairs, their childhoods, their complications living in South Africa, and the limits of being human. One denounces Coetzee; one finds him a family misfit; one had some good times with him…The book goes on this way.

The notion that this is Coetzee fictionalizing Coetzee while also probing for that elusive being--the author "behind" the books--isn't overplayed as Philip Roth would overplay it. There's no grand theory as to the interpenetration of the real and the fictional, or their interchangeability. As a consequence, the articulate documentary quality of Summertime, a title whose meaning eludes me, feels thin.

This is an idea book by a writer who can take just about any idea and do something highly professional with it. It's not a lot more than that. It lacks heat, plot, cunning, and a willingness to do more by way of introspection than put the author across as as something of an introverted clutz.

I haven't read it in a while, but I recall John Updike's memoir in essayistic fragments, Self-Consciousness, as a great deal more engaging and enlightening. He does his best to tell "the truth" about himself, a very hard thing to do. Coetzee, on the other hand, skillfully diddles with the post-modern notion that the author, Coetzee, isn't the point, his political views aren't the point, his lack of engagement with women isn't the point…the point is in his books, and this book, a fiction, isn't really a book, it's a thematic exploration…but of what?

The other day a friend asked me about a book we were discussing, "But don't you think it's well-written?" I said, "Yes, of course, the sentences are solid, the pace is good, the imagery is appropriate…but there's something to fiction that goes beyond that." I meant that fiction must have an internal dynamic and objective that is more than skill in managing words.

Late in this book, a former colleague tells the interviewer that where Coetzee fell short was in not taking chances, in deferring to the precepts of genre, in not wrecking conventional expections in the interests of passion. The larger reference here was to Russian writers of the 19th century--Gogol, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, I would think. Since Coetzee is playing the character being interviewed about him, it appears he has understood his own limitations well.

What's truly curious is that Summertime was "a finalist for the 2009 Man Booker Prize," which we hear about all the time as Great Britain's highest literary award. Why? Because even though a book about Coetzee by Coetzee isn't alive, it still deserves to be on such lists…because Coetzee is Coetzee?

I'm not trying to damn the book, just put it in perspective. It's sort of a readable, articulate book on a par with middle-grade wine, which is okay on a weekend when you're looking for a way to pass the time.

For a collection of my comments on contemporary fiction, see Tuppence Reviews (Kindle). -

This guy is something extra! He makes me less lonely, maybe more so than anyone else.

-

This is the most thinly disguised autobiographical fiction I have ever read. In fact I would hesitate to call it fiction at all. The only fictional element seems to be that Coetzee is suppposedly dead in this "novel".Still makes for interesting reading though. And he doesn't paint a very flattering picture of himself. I'll have to read Boyhood and Youth now, which are his other two autobiographical novels.