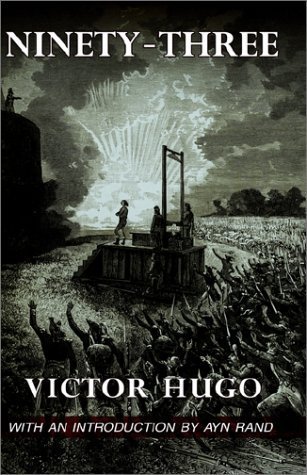

| Title | : | Ninety-Three |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1889439312 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781889439310 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 352 |

| Publication | : | First published February 19, 1874 |

1793, Year Two of the Republic, saw the establishment of the National Convention, the execution of Louis XVI, the Terror, and the monarchist revolt in the Vendée, brutally suppressed by the Republic. Hugo's epic follows three protagonists through this tumultuous year: the noble royalist de Lantenac; Gauvain, who embodies a benevolent and romantic vision of the Republic; and Cimourdain, whose principles are altogether more robespierrean.The conflict of values culminates in a dramatic climax on the scaffold.

Ninety-Three Reviews

-

Ich schreibe diese Eindrücke unmittelbar nach der Lektüre des Buches. Meine grundlegende Frage ist: Was war das? Ein historischer Roman? Eine Landschaftsbeschreibung Nordwestfrankreichs? Ein Jahresbuch des Jahres 1793? Oder gar ein Manifest des Humanismus vor dem Hintergrund der bestialischen Ereignisse (Gräuel wetteiferten mit Gräueln) während des royalistischen Aufstandes in der Vendée? Es scheint beinahe als hätten verschieden Autoren an dem Buch mitgewirkt. Es gibt zwei Erzählstränge, zum einen das Schicksal der Bettlerin Michelle Fléchard und ihrer drei kleinen Kinder, zum anderen die Verflechtungen des greisen Marquis de Lantenac, dem Anführer des Aufstandes, seines schwärmerischen Großneffen und ex-Vicomte de Gauvain, dem Kommandeur der republikanischen Truppen zu dessen Bekämpfung und des (ex-Abbé) Cimourdain, ehemals Gauvains Hauslehrer, einem jakobinischen Hardliner. All diese Personen sind fiktiv, allerdings ist Gauvain der französische Name des Tafelritters Gawain. Eine Sonderstellung nimmt die Szene zwischen den damaligen Revolutionsführern Robbespierre, Danton und Marat in einem Hinterzimmer der Gaststätte in der Rue du Paon ein, die einen Glanzpunkt des Romans bildet.

Hugo behält zunächst eine neutrale Position und verurteile das republikanische Ohne Gnade, keinen Pardon! genauso wie das royalistische Mitleid ist dummes Zeug. Seine Sympathie gilt den Underdogs die auf die Frage „Sind Sie Republikaner oder sind Sie Royalist?“ – „Ich bin Armer“ antworten, und bemerkt Es gibt noch einen schmerzlicher beklemmenden Anblick als einen brennenden Palast, das ist eine brennende Hütte. Mit der Zeit kristallisiert sich heraus, dass Hugo sehr wohl die Ideale der Revolution unterstützt, nicht aber deren Auswüchse zur Zeit des Wohlfahrtsausschuss und des Grande Terreur. Er sieht die aufständischen Bauern als Blinde, die nicht fähig waren, jenes Licht (der Revolution) zu begrüßen, stattdessen sich aber von ihren ehemaligen Herren und dem Klerus alles weismachen ließen. Sein Ideal verkörpert Gauvain und dessen Meinung

Ich habe von diesem Buch unglaublich viel über die Jahre der französischen Revolution gelernt. Trotzdem haben mich weder seine Komposition, noch der plötzliche Sinneswandel (die Verklärung) der Hauptpersonen am Ende überzeugt. Neben den anfangs erwähnten trage ich noch eine weitere Frage mit mir herum. Hugo schreibt: Die Vendée hat der Bretagne ein Ende gemacht. Ist also der Aufstand und seine Niederschlagung für das Weitgehende aussterben der spezifischen bretonischen Identität, Kultur und Sprache verantwortlich? Ich werde im Rahmen eines Miniprojekts mit einem Goodreads-Freund demnächst noch

Die Chouans oder die Königstreuen von Balzac lesen. Vielleicht komme ich dann einer Antwort näher.

Die Orthographie dieser Ausgabe ist zwar etwas gewöhnungsbedürftig, dafür ist sie flüssig zu lesen und enthält als Bonus die eindrucksvollen Illustrationen von Diogène Maillart. -

.

این رمان، آخرین اثر داستانی هوگوست. بعد از نوشتن بینوایان، به فکر افتاده که رمانی مختص انقلاب فرانسه بنویسد هرچند بینوایان پر است از ارجاعات به انقلاب. در نود و سه ما با چه مواجه می شویم؟ نویسنده چه برای ما آورده؟

سال 1793، سال آخر انقلاب کبیر فرانسه است. سالی که انقلابی ها پاریس را در اختیار دارند و برای فتح دیگر مناطق، ارتشی قدرتمند را روانه کرده اند. سالی که قرار است کار تمام شود و پادشاهی کنار برود. باز هم نویسنده توانسته بخش مهمی از تنوع مسأله را نمایش بدهد. هم صحنه های جنگ دارد هم گفتگو. هم موقعیت های شهری دارد هم طبیعت بی کران. هم عشق هست هم کشتار. همه هم پیچیده به یکدیگر و سازنده تودرتویی جداناشدنی.

یک ویژگی بارز کتاب آن است که می تواند ما را با نیروهای متخاصم همدل بکند. هم آنگاه که به اردوی شاه پرستان وارد می شود، ما نگران سرنوشت این جبهه هستیم، و هم زمانی که انقلابیون را دنبال می کند، ما پیگیر پیروزی ایشانیم. بدین ترتیب و با چنین رویکردی به داستان، هوگو جلوی پیشداوری ما را می گیرد. اگر هم پیشداوری داریم، سعی می کند آن را بر هم بزند. نمی خواهد یک نتیجه محسوس گرفته شود و داستان به سرعت جمع شود. او تا جایی که امکان دارد، می خواهد مخاطب را به سوژه داستانی نزدیک کند. در چنین شرایطی حکم کردن برای مخاطب سخت می شود. اجازه نمی دهد خواننده را��ت به سمتی بغلتد.

رمان همواره شمشیر را آخته، توپ را آماده شلیک و آتش را در شرف سوزاندن نشان می دهد. یا خون ریزی است و آتش زدن است، یا حرف از خونریزی است. چه فاصله ای دارد این تصویرهای پاریسی، از فانتزی های قجری روشنفکران ایرانی از پاریس! گیوتین بالای سر رمان آماده سقوط است تا سرها را از پیکرها جدا کند. نود و سه مطلق بودن حاکمیت دولت مدرن را نشان می دهد. تسخری است به ایده «هم این هم آن» برای آن ها که نمی فهمند تجدد بنیانی جز بریدن دنباله سنت ها ندارد. یکی باید برود تا دیگری بیایند. آینده جدید است و رفتنی، گذشته.

اما رمان اینجا متوقف نمی ماند. سه مرد با سه نوع خلق و تفکر در نقطه ای به هم می رسند. مارکی دو لانتوناک اشراف است و تنها بازمانده قدرتمند پادشاهی. با حکومت جمهوری مخالف است و برای بازگشت فرانسه به دوران گذشته می جنگد. گُووان اشرافزاده است، اما به صف انقلاب و جمهوری خواهان پیوسته است. به انقلاب اعتقاد دارد. جیموردن کشیشِ جمهوریخواه، از هم سلکان قدیم بریده و به صف انقلاب پیوسته است. هم در علم، گذشته را رها کرده و هم در سیاست. حافظ قانون است. این سه در همانجایی به هم می رسند که رمان با آن شروع می شود. مادری با سه بچه در معرض خطر است. این بچه ها کانون روایت رمان هستند.

با همه وجود در نظر گرفتن جنبه های روانشناختی، جامعه شناختی، سیاسی، تاریخی، فلسفی و ادبی، باز هم برخی همه گره های رمان باز نمی شوند. فهم علت بخشی از رفتارها به زیرلایه های رمان بستگی دارد که مهمترینش، بنیاد الهیاتی آن است. در سیمای لانتوناک، ته چهره یهوه دیده می شودآنجا که سرزمینی را به تلی از خاک و خاکستر مبدل می سازد، و آنجا که می بخشاید. در چهره گووان و جیموردن هم صورتی از مسیح دیده می شود. هر کدام به نحوی منجی هستند و منادی عدالت. گویی موقعیت آخر رمان، صحنه رویارویی یهوه و مسیح است. خدای اعلی با مسیح که تجسد خود خداست روبرو می شود. آیا یهوه می میرد تا مسیح زنده بماند؟ این همان برداشت معروف ما از تجدد است. گذشته می رود تا نو بماند. اما ویکتور هوگو بسیار عمیق تر از ین تبیین های روشنفکرانه به مسأله نگاه می کند. مگر یهوه مردنی است؟ و یا مگر مسیح می تواند از تعین فرار بکند؟ هردو جاویدند و هردو رفتنی. چطور ممکن است؟ رمان را بخوانید تا متوجه ماجرا بشوید. -

Poslednji Igoov roman je i moj šesti susret sa nekim njegovim delom. Šta reći no da niko nije pisao romatičarske istorijske romane kao majstor Viktor. Radnja je smeštena za vreme francuskog građanskog rata između republikanaca i rojalista u Vandeji i uspostavljenja Jakobinskog terora - giljotina, kako će reći jedan od junaka, ćerka Robespjera i na silu udate Francuske. U njemu imamo sve što očekujemo od Igoovog romana: Veliki broj junaka – trećina jadnika, trećina zadrtih ljudi sa jednom idejom kroz život, trećina istorijskih figura – upletenih u mrežu narativa koji su prepuni preokreta, gotičkih kula, krvoprolića, humora, mesečine, brodova zahvaćenih burom, iskakanja iz magle, pukog slučaja, velikih etičkih pitanja, pa i onih trenutaka adrenalinskih neubedljivosti kada čitalac uzvikne „MA, DAJ!“ a zapravo želi da kaže „DAJ, JOŠ!“, nego se stidi. Negde do kraja, autor sasvim očekivano poubija više od pola svojih junaka. Igo nikad nije tvrdio da piše istorijske romane već legende.

Ideja vodilja evropskog devetnaestovekovnog romana sadržana u pokušaju da se odgovori na pitanje šta znači i kako biti dobar čovek, u ovom delu je pomerena prema njenoj varijaciji izraženu kroz problem: da li čineći dobro delo čovek može da načini mnogo više zla na duže staze? To jest - da li kada pomognemo ranjenom vuku postajemo odgovorni za smrt ovaca? Poput refrena i neugašenog plamena ova dilema se predaje iz ruke u ruku različitim junacima zajedno sa nasiljem koji se poput poređanih domina obrušavaju u uzročno-posledičnom nizu. Široki eskursi, autorski komentari i esejistički delovi u romanu pokušavaju da uobliče poslednju Igoovu misao o Francuskoj revoluciji, ali i smislu istorije, što je zanimljivo posebno jer je autor imao dugu i kompleksnu, pa i kontradiktornu političku karijeru. Ovde zauzima stranu republikanaca, ali odaje i dužno poštovanje rojalistima. Ipak, pokušaj pranja republikanskog nasilja ostaje najintrigantniji, tim pre što, Summa summarum, njegova romantičarska mistika o progresu čovečanstva (u Zmajevom stilu „Gde ja stadoh, ti produži“) ipak ostaje nepomirena sa veličanstvenim mrakom završetka romana. Situacija je još kompleksnija, ako se računa da čitaoci u trenutku izlaženja romana (1874), u ovom delu nisu tražili Igoove odgovore o Vandeji, Francuskoj revoluciji i događajima od pre 100 godina, nego stav vezan za krvavo gušenje Pariske komune.

A kako Igo začarava rečima i kako uvodi likove nek posluži sledeći primer:

Simurden je bio čista, ali mračna savest. Po prirodi je bio bezuslovan. Bio je sveštenik što je ozbiljna stvar. Čovek kao i nebo, može biti mračno vedar; dovoljno je da nešto stvori u njemu tamu. Sveštenstvo je u Simurdenu stvorilo mrak. Ko je bio pop, taj ostaje pop. Ono što u nama stvara noć, može izazvati i zvezde. Simurden je bio pun vrlina i istina, ali su one blistale u tami...

Nekoliko stranica kasnije autor završava Simurdenov portret rečima: Niko danas ne zna za njega. U istoriji ima tih strašnih, nepozantih ljudi.

Legenda kaže da je negde tamo u Gruziji, u nekoj crkvenoj školi, lik Simurdena ostavio dubok utisak na mladog Josifa Staljina. -

Dec. 2017 - Fascinating book.

This is my first book by Hugo and I can easily see why he is renowned for his powerful and beautiful writing. The descriptions of the characters in the book are so poignant. The images of the settings are haunting. The drama is unforgettable.

One will never use the term "loose cannon" again loosely after reading the chapter describing what that really meant to the sailors on a fighting ship.

This book was read superbly by Lisa VanDamme for a new project she has just started at:

https://readwithmebookgroup.com/

She had taught and read this book many times to her students over the years, then decided to open it up to adults on Facebook and the general web. She is a marvelous narrator and discussion leader for key points in and about the book.

BTW, some folks might be interested to know that this book was one highly recommended by Ayn Rand. She was a huge fan of Victor Hugo, and this book in particular.

Hat tip: Brian Surkan - thank you for cluing me in to this wonderful audio book. -

The French Revolution was not simply capturing the Bastille and living happily ever after. As with all revolutions, there were unexpected results.

One of these became known as the Reign Of Terror, lasting from September 1793 to July 1794. Victor Hugo deals with this painful topic in his final novel, 'Ninety-Three.

I'm so close to speechless I can only say that every single person on the planet should read this book now. -

Free download available at

Project Gutenberg.

Translator: Aline Delano

Release Date: July 6, 2015 [EBook #49372]

Language: English

Produced by Laura N.R. and Marc D'Hooghe (Images generously made

available by the Hathi Trust - and by Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France) for the illustrations.)

This book has several translations but we found only this one, made by Aline Delano, to be more closer to the original French text. She also translated from the Russian the following books: "The Blind Musician" by Vladimir Korolenko; "The Kingdom of God is Within You, What is Art," by Leo Tolstoy.

The original file was provided by

Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Critical Note by Robert L. Stevenson (from "The Works of Victor Hugo, Vol. VII, Jefferson Press, 190-?)

In Notre Dame, Les Miserables, The Toilers of the Sea and The Man Who Laughs, one after another, there has been some departure from the traditional canons of romance; but taking each separately, one would have feared to make too much of these departures, or to found any theory upon what was per- haps purely accidental. The appearance of Ninety-Three has put us out of the region of such doubt. Like a doctor who has long been hesitating how to classify an epidemic malady, we have come at last upon a case so well marked that our uncertainty is at an end. It is a novel built upon a sort of enigma," which was at that date laid before revolutionary France, and which is presented by Hugo to Tellmarch, to Lantenac, to Gauvain, and very terribly to Cimourdain, each of whom gives his own solution of the question, clement or stern, according to the temper of his spirit. That enigma was this: "Can a good action be a bad action? Does not he who spares the wolf kill the sheep?" This question as I say, meets with one answer after another during the course of the book, and yet seems to remain undecided to the end. And something in the same way, although one character, or one set of characters, after another comes to the front and occupies our attention for the moment, we never identify our interest with any of these temporary heroes nor regret them after they are withdrawn.

Page 12:

I was in Paris on the 10th of August. I gave Westerman a drink. Everything went with a rush in those days! I saw Louis XVI. guillotined,--Louis Capet, as they call him. I tell you he did*n’t like it. You just listen now. To think that on the 13th of January he was roasting chestnuts and enjoying himself with his family! When he was made to lie down on what is called the see-saw, he wore neither coat nor shoes; only a shirt, a quilted waistcoat, gray cloth breeches, and gray silk stockings. I saw all that with my own eyes.

Page 60:

“This man who is among us represents the king. He has been intrusted to our care; we must save him. He is needed for the throne of France. As we have no prince, he is to be,--at least we hope so,--the leader of the Vendėe. He is a great general. He was to land with us in France; now he must land without us. If we save the head we save all.”

Page 135-136:

'93 is the war of Europe against France, and of France against Paris. What then is Revolution? It is the victory of France over Europe, and of Paris over France. Hence the immensity of that terrible moment '93, grander than all the rest of the century. Nothing could be more tragic. Europe attacking France, and France attacking Paris,--a drama with the proportions of an epic.

Page 139:

The Gironde, speaking in the person of Isnard, temporary president of the Convention, had uttered this appalling prophecy: "Parisians, beware! for in your city not one stone shall be left resting upon another, and the day will come when men will search for the place where Paris once stood." This speech had given Birth to the Évêché.

Page 209:

At the time when the death-sentence of Louis XVI. was passed, Robespierre had eighteen months to live, Danton fifteen, Vergniaud nine, Marat five months and three weeks, and Lepelletier-Saint-Fargeau one day! Brief and terrible was the breath of life in those days.

Page 218:

Revolution is a manifestation of the unknown. You may call it good or evil, according as you aspire to the future or cling to the past; but leave it to its authors. It would seem to be the joint product of great events and great individualities, but is in reality the result of events alone. Events plan the expenditures for which men pay the bills. Events dictate, men sign. The 14th of July was signed by Camille Desmoulins, the 10th of August by Danton, the 2d September by Marat, the 21st of September by Grégoire, and the 21st of January by Robespierre; but Desmoulins, Danton, Marat, Grégoire, and Robespierre are merely clerks.

Page 305:

"Liberty, equality, fraternity,--these are the dogmas of peace and harmony. Why give them so terrible an aspect? What are we striving to accomplish? To bring all nations under one universal republic. Well, then, let us not terrify them. Of what use is intimidation? Neither nations nor birds can be attracted by fear. We must not do evil that good may come. We have not overturned the throne to leave the scaffold standing. Death to the king, and life to the nations. Let us strike off the crowns, but spare the heads. Revolution means concord, and not terror. Schemes of benevolence arc but poorly served by merciless men. Amnesty is to me the grandest word

in human language. I am opposed to the shedding of blood, save as I risk my own. Still, I am but a

soldier; I can do no more than fight. Yet if we are to lose the privilege of pardoning, of what use is it

to conquer? Let us be enemies, if you will, in battle; but when victory is ours, then is the time to be

brothers."

Page 467:

Was it then the object of Revolution to destroy the natural affections, to sever all family ties, and to stifle every sense of humanity? Far from it. The dawn of '89 came to affirm those higher truths, and not to deny them. The destruction of bastiles signified the deliverance of humanity; the overthrow of feudalism was the signal for the building up of the family.

Page 486:

The genius of France was made up from that of the entire continent, and each of its provinces represents a

special virtue of Europe; the frankness of Germany is to be found in Picardy, the generosity of Sweden

in Champagne, the industry of Holland in Burgundy, the activity of Poland in Languedoc, the grave dignity

of Spain in Gascony, the wisdom of Italy in Provence, the subtlety of Greece in Normandy, the fidelity of Switzerland in Dauphiny.

Page 505:

"Grand events are taking form. No one can comprehend the mysterious workings of revolution at the present time. Behind the visible achievement rests the invisible, the one concealing the other. The visible work seems cruel; the invisible is sublime. At this moment I can see it all very clearly. It is strange and beautiful. We have been forced to use the materials of the Past. Hence this wonderful '93. Beneath a scaffolding of barbarism we

are building the temple of civilization. -

Magnifico, intenso come d’altronde tutto ciò che Hugo abbia scritto. Il mio porto sicuro.

“Il Novantatré” è l’anno del terrore e ultimo libro di Hugo. Un avvincente romanzo storico che appassiona e coinvolge dalla prima all'ultima pagina.

La storia di tre "caratteri" scolpiti con stupefacente maestria: il marchese Lantenac, uomo leale del re, dedito all’onore antico; Cimourdain, un ex prete, uomo austero e inflessibile, implacabile come il fuoco della Rivoluzione; e infine Gauvain, giovane aristocratico nipote di Lantenac, allievo di Cimourdain, passato al popolo. Un giovane spirito mosso dalla Rivoluzione che ritrova se stesso nel suo ultimo libero volo.

Personaggi indimenticabili che Hugo disegna in modo sublime. Temperamento, ideali, questo libro è un viaggio profondo nella loro coscienza. E in questo Hugo è imbattibile. Buono e cattivo, giusto e sbagliato si fondano in un tutt’uno, come spiriti mossi dal vento, il vento della rivoluzione che tutto abbatte e tutto trasforma.

I dialoghi sono di un'intensità e bellezza rara, il finale sorprendente. Emozioni che solo una grande penna poteva imprimere sulla carta. -

This is pretty typical of the author's work and I love it. It's full of hard hitting moments, as well as themes and messages, you can notice Hugo's interest in history which never romanticizes it and he loves to bring back characters, relationships and mirrored situations throughout the book, all things I already loved in Les Mis.

While he never makes you feel for or lets you know a character in the same way we expect from modern books, he still explores and characterizes them so well. He isn't afraid to have good actions with bad consequences or questionable characters do good things, while still staying on theme and supporting his moral views. While it can be descriptive for a short time and a part in the middle was a bit less exciting, I was incredible intrigued by everything going on. I just adore Hugo's plots and writing and this might be a new favourite for me, other than Les Miserables of course. -

La Terreur

Un romanzo di grande spessore, in ogni senso, questo che Victor Hugo pubblicò nel 1874, ultimo tra i suoi capolavori! Uno spettacolare affresco di un periodo molto particolare nell'ambito di quell'avvenimento epocale che fu la Rivoluzione Francese: il 1793, l'anno del Terrore.

La vicenda si svolge principalmente nella Vandea, terra “aspra e forte che nel pensier rinnova la paura” e che, dopo la caduta della monarchia e la decapitazione del re Luigi XVI, insorge contro il nuovo regime repubblicano, dando così avvio a una feroce guerra civile combattuta fra le truppe regolari francesi e le bande di contadini vandeani pericolosamente nascoste tra i fitti boschi della regione. A capo di queste ultime, il marchese di Lantenac, vecchio aristocratico fedele ai valori dell'Ancien Régime che, con le forze raccolte attorno a sé, diventa ben presto una spina nel fianco che il governo repubblicano intende sradicare una volta per tutte.

Sullo sfondo della grande Storia, che catapulta il lettore addirittura al cospetto della triade rivoluzionaria Robespierre-Danton-Marat e persino nel bel mezzo di una seduta dell'assemblea della Convenzione, si muovono dunque diversi personaggi con le proprie piccole storie, dal nobile Lantenac alla miserabile vedova Michelle Fléchard, mater dolorosa che vaga alla ricerca ostinata dei suoi tre bambini dopo che le vengono portati via durante gli scontri.

“Une veuve, trois orphelins, la fuite, l'abandon, la solitude, la guerre grondant tout autour de l'horizon, la faim, la soif, pas d'autre nourriture que l'herbe, pas d'autre toit que le ciel.”

E proprio le vicissitudini di questa umile famigliola, trovatasi suo malgrado tra le violenze della guerra civile, offrono pagine di grande intensità, rivelandosi altresì determinanti per la sorte del marchese di Lantenac.

Nonostante un inizio che sembra stentare a entrare nel vivo della storia e la pesantezza di alcuni passaggi qua e là nel corso della narrazione, da un certo punto in poi il romanzo si fa via via decisamente più appassionante e non avaro di colpi di scena capaci di tenere ben desta l'attenzione di chi legge, complice una scrittura magnifica, potente, a tratti disarmante (godibilissima anche in lingua originale!) che spesso s'interroga, e ci interroga, su temi etici. Attraverso i suoi personaggi, infatti, Hugo ci mostra come bene e male non sempre abbiano un confine poi così netto e che pure il colpevole di crimini indicibili si possa riscattare salvando la vita a tre poveri bimbi.

Vecchio e nuovo, inoltre, si contrappongono su più livelli: da un lato, Lantenac e suo nipote, il giovane capitano Gauvain, fiero e irriducibile monarchico il primo, convinto repubblicano il secondo; dall'altro, lo stesso Gauvain e il suo vecchio precettore Cimourdain, i quali, benché entrambi sostenitori dell'ideale repubblicano, ne incarnano due visioni differenti, nonché due concezioni inconciliabili della giustizia in nome della quale si deve agire: dura e inflessibile, pressoché spietata, per Cimourdain che con quel suo “Force à la loi!” nel momento estremo ribadisce con durezza il proprio ruolo di delegato del Comitato di salute a pubblica a dispetto del suo essere in origine un prete, al contrario del suo allievo di un tempo, secondo cui la giustizia dev'essere anche capace di atti di clemenza, controbilanciando le colpe con i meriti dell'individuo, in nome di un senso di umanità che non dovrebbe mai venire meno.

Un romanzo che si fa esplicita condanna della guerra in generale e dell'insensatezza della violenza (anche di quella da parte dello Stato che mette a morte i propri cittadini, nel solco, del resto, di quanto già espresso oltre quarant'anni prima con “L'ultimo giorno di un condannato a morte”), un finale inatteso e sorprendente, in cui si soffre e si spera fino all'ultimo straziante rullo di tamburi, mentre sfilano suoni e immagini che soltanto una grande penna poteva imprimere su carta. -

This completes for me the trio of novels that tell of the conflict between the Royalist resistance in Brittany and the Republican Revolutionaries after the beheading of Louis XVI. I think I serendipitously read them in the "right" order, which happens to be in publication order:

The Chouans, by Balzac,

La Vendee by Trollope, and this by Hugo. They each have a somewhat different perspective.

The middle part of this was a slog, but it was sandwiched between two parts that were compelling. The sloggy part felt more like nonfiction and included lots of names with which I was unfamiliar, but were probably part of any history learned in school in France. I suspect many - both US and others -might just as easily be unfamiliar with the minor players of the US Revolution. But the major players made up a part of this section, too, and one in particular, Cimourdain, was instrumental to the exciting third part.‘93 is a year of intense action. The tempest is there in all its wrath and grandeur. Cimourdain felt himself in his element. This scene of distraction, wild and magnificent, suited the compass of his outspread wings. Like a sea-eagle, he united a profound inward calm with a relish for external danger.

And the Head of the Committee of Public Safety, Robespierre, tells us:"Listen, Danton; foreign war is as nothing compared with the dangers of civil war. A foreign war is like a scratch on the elbow, but civil war is an ulcer which eats away your liver. Here is the sum and substance of all that I have just read to you: the Vendée, which has hitherto been divided among many chiefs, is about to concentrate its forces. Henceforth it is to have one leader"

Although I highlighted a bit more elsewhere, this was enough to set the stage for this novel and the conflict it describes. Hugo felt compelled to a bit more philosophizing than I like in a novel. If I were more a student of the French Revolution, and especially this period of the Reign of Terror, I might have appreciated it more. As it is, this sits on the border between 3- and 4-stars. The compelling parts are enough to nudge it up.

-

“El verdadero punto de vista de la revolución es la irresponsabilidad: ninguno es inocente, pero tampoco hay ningún culpable”

Aunque está novela es menos leída que Los miserables, me ha parecido de mayor calidad. El tema es la revolución francesa, desde luego que hay aventuras militares que cautivarán a los más jóvenes.

Entre los personajes aparecen Robespierre, Dantón y Marat. Así que la novela da la oportunidad de investigar sobre personajes históricos y hechos.

En cuanto a personajes ficticios quien se lleva la palma es Cimourdain, un sacerdote metido en política, bastante apasionado con su sed de justicia.

Una delicia de novela pese a su complejidad. Por esta novela tendré que quitar una estrella a Los miserables. -

این موضوع در نوشته های ویکتور هوگو قابل ستایش هست که در نوشته هاش بیشتر به بُعد انسانی و اجتماعی داستان می پردازه، و کمتر به مسائلی از قبیل نوع پوشش و ظاهر آدم ها و حتی اموراتی چون صرف غذا و از این دست اهمیت میده.

این کتاب آخرین اثر هوگو هست، همونطور که از اسم کتاب پیداست داستان بیشتر حول محور سال 1793 ��عنی سال چهارم انقلاب فرانسه که مصادف با اعدام لویی شانزدهم هست می پردازه، شخصیت های اصلی داستان مارکی دو لانتوناک از اشراف فرانسه و طرفدار سلطنت طلب ها (سفیدها) ، گوون اشراف زاده ای که به صف جمهوری خواهان(آبی ها) پیوسته و کشیش سیموردن جمهوری خواه. هر کدام از این شخصیت ها نسبت هایی با یکدیگر دارند که خواننده در روند داستان با این موضوع آشنا میشه.

هوگو روایت کتاب رو بسیار دلنشین در وصف عقاید انقلابی و احساسات مادرانه یک مادر روستایی نسبت به فرزندانش شروع می کنه و پایان کتاب رو بسیار تامل برانگیز به پایان می رسونه. -

L’anno del Grande Terrore; la Repubblica minacciata dai nemici esterni sul Reno viene attaccata dai nemici interni, i federalisti, ma soprattutto la Vandea. Grande narratore Victor Hugo, quasi uno storico che ricostruisce gli avvenimenti nell’Ovest francese, la Bretagna in particolare, con l’insurrezione dei contadini nel bocage e nelle foreste nella primavera-estate del 1793. Puntualissime descrizioni di luoghi reali e immaginari (il cupo e inquietante maniero de La Tourgue) introducono e ambientano drammi umani narrati dinamicamente con dovizia di particolari. Anno terribile il Novantatré, l’anno in cui la Rivoluzione dispiega tutta la sua micidiale potenza e idealità; ma anche il più funereo e funesto fanatismo che sconfina continuamente nel sadismo e nella malvagia perversione. Danton, Marat e Robespierre compaiono anch’essi, ma poi se ne stanno sullo sfondo grandioso della Parigi rivoluzionaria e ardente. I protagonisti, tanti, invece si muovono, soffrono, lottano, si ammazzano con furore nelle foreste e nei villaggi della Bretagna. Da una parte i soldati repubblicani della guardia nazionale guidati dall’ex visconte il capitano Gauvain e dal commissario politico, l’ex abate Cimourdain, mandati a reprimere e sterminare i rivoltosi; dall’altra i lealisti, i contadini insorti guidati dai loro capi, sui quali signoreggia venerato da tutti il marchese di Lantenac. Come la Rivoluzione è un intreccio di pulsioni omicide e slanci purissimi di idealità, così personaggi che ci presenta Hugo (tra i quali, i principali: Gauvain, Cimourdan e Lantenac) sono un impasto di bene e male, tenebra e luce, fanatismo e generosità, inflessibilità e magnanimità. A dosi diverse, molto variabili. Hugo vuole salvare la Rivoluzione, il bilancio finale, il saldo positivo del guadagno sulle perdite. La Rivoluzione è costata tantissimo sangue, tantissimo sangue anche innocente, ma ha liberato la Francia, e da lì l’Europa, dal dispotismo, dal feudalesimo, dall’arbitrio, dal privilegio e dalla superstizione religiosa.

Scritto a partire dal 1862, il libro fu pubblicati nel 1874. A volte si sente, soprattutto nell’analisi psicologica dei personaggi, che è stato scritto 150 anni fa, ma in complesso è un gran bel racconto, godibile, interessantissimo anche per gli spunti storici che continuamente propone, e forsanche (cum grano salis) per le riflessioni che il grande Victor Hugo fa su quel terribile anno. -

Voici mon roman favori de Hugo. C’est celui qui m’a fait la plus belle impression, malgré la très vive concurrence que lui font Les Misérables et de Notre-Dame de Paris.

Je suis conscient de la singularité de ma préférence et j’aimerais tenter de vous la faire comprendre.

Tout cela tient à ma perception de Hugo. Pour moi, c’est l’homme magistral des lettres françaises. À mon avis, il a su, mieux que personne, écrire en prenant une perspective à la fois élevée et pleine d’une compréhension généreuse et touchante. Cette particularité tient du génie, du miraculeux. Je ne crois pas qu’on puisse l’expliquer. Il a pu disposer d’un esprit tout naturellement grand, exactement comme d’autres disposent d’une grande taille, d’une grande fortune, etc., c’est tout.

Cette grandeur se manifeste de la manière la plus parfaite dans ses poèmes, mais je la sens même dans ses pamphlets, ouvrages dont le style et les sujets sont, par définition, on ne peut plus terre à terre. Et parmi ses romans, celui où cette particularité, qui fait pour moi le charme unique des ouvrages de Hugo, apparaît de la manière la plus éclatante, c’est Quatrevingt-treize.

Hugo s’est très bien documenté sur la période de la terreur pour écrire ce livre, dont l’horizon est la lutte entre révolutionnaires et monarchistes. Malgré ses convictions personnelles favorables à la révolution, Hugo dépasse sa perspective de simple citoyen pour exposer d’une manière juste et généreuse les tares et qualités de chacun des partis.

On s’y sent, tout en douceur, transporté en survol au-dessus des évènements terribles de cette période troublée.

Un pur délice. -

رواية جميلة ككل أعمال فيكتور هوجو

ألقي الضوء في اسم الرواية علي أجمل ما فيها .ز الأطفال الثلاثة

وصوّر من خلالهم الحرب بين الزرق والبيض أو الجمهورية والملكية

طبعا ما يميز فيكتور هوجو الحبكة الرائعة في القصة ، والترابط في الأحداث ، والتسلسل والتناسق والدقة والواقعية -

I have read that the English translation is not nearly as good as the original French but the only French I know is 'French fry', so I had to settle. Not that that is a bad thing because in my opinion this was still a great classic from Hugo. This was the final work of the author of such masterpieces as

Les Miserables and

The Hunchback of Notre Dame, telling of the French revolution of 1793. Admittedly, I had never heard of the book and only know about it because I came across an old copy of it in an antique book shop. And I'm glad I did because it is another wonderful piece of classic literature for my collection. -

La scrittura di Hugo ha un livello impareggiabile; è pathos su carta, ma non diventa mai pomposa: resta raffinata, acuta, lucida. Arriva dritta all’obiettivo, è precisa e ricca allo stesso tempo. Certo, ha molto di teatrale, come quella di Dostoevskij, ma non suona mai meramente gestuale.

Non è, tra l’altro, solo questo tipo di scrittura ad accomunare Hugo e Dostoevskij; in Novantatré si trovano diversi temi ben esplorati anche dallo scrittore russo. Se apparentemente il romanzo di Hugo si incentra sulla lotta tra la resistenza realista e il governo repubblicano nato dalla Rivoluzione, in realtà racconta la storia di una lotta tra idee e umanità, e di una lotta all’interno di una coscienza. Con un anticipo di cinque anni sui Fratelli Karamazov, Hugo parla dell’uomo come campo di battaglia tra Satana e Dio, quasi con le stesse parole che userà Dostoevskij:

Mai, in nessun combattimento, era stato più visibile Satana e con lui Dio.

Quella lotta aveva avuto per arena una coscienza.

La coscienza di Lantenac.

Adesso era ricominciata, forse ancora più accanita e decisiva, in un’altra coscienza.

La coscienza di Gauvain.

Quale campo di battaglia è l’uomo!

Ancora, come una decina di anni prima Delitto e castigo aveva raccontato la storia di un delitto non compiuto fino in fondo, anche qui si osserva:

Che aveva fatto di tanto ammirevole?

Non aveva persistito, ecco tutto.

Dopo aver ordito il delitto, aveva indietreggiato, pieno di orrore per se stesso.

Che l’influenza tra i due scrittori sia o meno diretta, è interessante notare come per entrambi è centrale il problema della coscienza. Per tutti e due il nodo di interesse della storia è il comportamento di una coscienza di fronte a un’idea astratta: che sia il volersi dimostrare pari di Napoleone come Raskol’nikov o il difendere l’inflessibilità delle leggi rivoluzionarie a tutti i costi, l’obiettivo astratto dettato da un’ideologia porta sempre l’uomo al di fuori della vita:

Cimourdain tutto sapeva e tutto ignorava. Sapeva tutto della scienza e ignorava tutto della vita. Donde la sua rigidezza. Aveva gli occhi bendati come la Temi di Omero. Aveva la cieca certezza certezza della freccia che vede unicamente il bersaglio e a esso si dirige. Nelle rivoluzioni, niente di più temibile della linea retta. Cimourdain tirava sempre, fatalmente, dritto.

Come osserverà Vasilij Grossman in Vita e destino un centinaio di anni dopo, è il destino a essere dritto e lineare, mentre la vita sta nella libertà e nella varietà; l’uomo non deve essere guidato da un bene utopico e astratto, quanto piuttosto dalla propria bontà e dalla propria coscienza. In Novantatré, anche se la Rivoluzione è vista come un fattore di progresso, il perseguimento della sua riuscita non giustifica lo sprezzo della legge naturale e trascendente. La storia fa il suo corso, come una tempesta, ma in questa tempesta l’uomo è dotato di una bussola: la propria coscienza; è con questa che alla fine dovrà fare i conti, molto più che con la contrapposizione delle ideologie. -

-

Nuevamente Víctor Hugo desborda mi vena romántica con su talento inigualable. No cabe duda que este glorioso autor francés siempre estará muy cerca de mi sensibilidad. Cada vez que uno entra a sus páginas de inmediato nos conecta a su mundo poblado de personajes llenos de valores humanos como el honor, la valentía, la verdad, la justicia y la dignidad, valores que se destacan nuevamente en las páginas de este libro.

El telón de fondo de esta novela es la Revolución Francesa de 1789, aunque el relato se centra en el año 1793, año en que fue decapitado Luis XVI y año en que se sucedieron algunos de los hechos más violentos y sangrientos de la historia de Francia, pero dentro de este terror, también acontecieron hechos heroicos alentados por admirables y genuinos ideales por lograr una mejor nación y un mejor mundo. Creo que pocos acontecimientos de tipo bélico han sido inspirados por sueños tan románticos y por nobles ideales humanos para superar la propia condición humana como sucedió en la Revolución Francesa.

Dentro de este telón de fondo destacan dos temas de singular carga histórica y emotiva. Dos relatos que hace Víctor Hugo de manera notable: la descripción y la importancia que le concede al rol que asumió la Convención Nacional misma que tomó las riendas de Francia para diseñar la primera República del mundo, una República que buscaba allanar el tema político y diseñar e implementar una forma de gobierno más justa e igualitaria; pero este no fue el tema principal, lo que conmueve y da que pensar es que la Convención Nacional emitió casi 10 veces más decretos de carácter humano para protección y auxilio de los ciudadanos más desprotegidos, que los que tenían que ver puramente con la política.

El otro tema culminante que es tratado con gran vastedad por el autor es la contrarrevolución que surgió espontáneamente entre el campesinado de una región de Francia que se oponía a la República recién instaurada. Ellos no querían ser libres, querían a su Rey. No sabían conducirse solos, ¡no conocían la libertad!; necesitaban su brújula y a un amo a quien obedecer en todo. Ese movimiento respaldado en su momento por Inglaterra fue llamado La Vendee, situado básicamente en la región de Bretaña y el cual sigue siendo motivo de estudio y debate historiográfico para conocer sus reales orígenes, motivaciones y consecuencias.

Por estas páginas pasan fugazmente Robespierre, Saint-Just, Danton y Marat los principales hombres de estos años en Francia, los hombres terribles y decididos a todo con tal de instaurar la República y exterminar cualquier viso del antiguo realismo. Pero los personajes principales de esta novela son el Marqués de Lantenac y Gauvin. Tío abuelo y sobrino respectivamente, y a quienes las circunstancias políticas los han llevado a ser enconados y mortales rivales. Los últimos capítulos se desarrollan alrededor y dentro de una especie de castillo bretón antigua propiedad de los antepasados de los protagonistas. La antigua construcción de la Tourgue representa el más acendrado feudalismo ya que ahí se criaron los nobles bretones de rancio abolengo. Es ahí donde se libra la última batalla entre tío y sobrino; entre las ideas del pasado y la construcción de un mundo futuro. La Revolución, es decir el hombre del porvenir, tendrá que destruir simbólicamente y acorde con el destino, aquella magnífica Torre, símbolo del pasado perteneciente a la clase gobernante y tiránica durante más de 15 siglos y ahora convertida en un obstáculo para el hombre del porvenir y de la nación futura.

Esta historia construida alrededor de estos interesantes y apasionantes temas es tratada de una manera romántica como corresponde a la pluma de Víctor Hugo, aunque también la envuelve, como tal vez él sólo sabe hacerlo, en un delicado y esplendoroso velo que va del misticismo apasionado a la poesía más profunda y trágica. El poder de su pensamiento y la magia de su capacidad de expresión nuevamente nos hacen cimbrarnos, nos azota con una lluvia de estrellas, de donde él ha sabido utilizar su mano maestra para desplazar las nubes que enturbian el cielo azul de la humanidad. Para mí, sigue y seguirá siendo uno de esos autores que exaltan el espíritu.

Una vez más Víctor Hugo se decanta por todo lo humano. Los diálogos finales entre Tío y sobrino y entre sobrino y tutor, electrizan las páginas de la novela. El rancio y noble pensamiento del viejo Marqués hace también por momentos inclinar la balanza hacia el linaje, la nobleza, la tradición, el respeto, la disciplina, la lealtad y otras cualidades que se destacan en la Nobleza. Pero más adelante, casi al final, el sobrino le espeta a su tutor: “no era más que un Noble y habéis hecho de mí un ciudadano”. Contundente frase que de nuevo inclina la balanza hacia el otro lado.

Si algún día me pidieran que escogiera a algún notable habitante de los siglos modernos para crear al hombre, seguramente escogería a Víctor Hugo. -

What an amazing novel. Beautifully crafted, I love the narrative, with the characters standing in as avatars for ideas, and interplay with symmetry and contrasts between the various characters and ideas. Easy to mess up such a dynamic by rendering it too simplistically, but I think Hugo infuses a great level of nuance and subtlety to the enterprise helping ensure his novel doesn’t turn into a 1-dimensional parody.

Personally I love the stylization of the writing, lyrical and poetic, and so much fantastic imagery (really this part is just awesome!). Sometimes the 19th century novel goes a bit bonkers with meandering descriptions of geography, place, customs, objects. This can be kind of obnoxious, but this book only has a few such moments and I really don’t mind as the quality of the writing and story are too good. But these meanderings in the 19th century novel are just one of those things I try to buttress myself against, I usually don’t mind so much but sometimes it is an avalanche of words that doesn’t advance plot or character (at least doesn't seem to in my eyes) and try as I might it can break my patience. Like I said though, this book only has a few such moments, and usually when this is happening it involves a broader metaphor that seems to make sense for developing the story and message of the book.

This story takes place with the historical backdrop of the French Revolution year 1793, as the Terror is getting under way. It pits two opposing forces, revolutionary and reactionary. Progressive vs traditional. Duality is featured throughout the book. And yet there is nuance to the political analysis and views. And the historical background was very interesting and informative for me (some of the interesting alliances including reactionary alliance between nobles-rural poor/paysans-catholic elements vs revolutionaries emanating from various segments of city society. Of course this wasn't all cut and dry, but there were interesting linkages going on, and internecine struggles for supremacy between the subgroups on each side). The story seems to capture an essence of the times, intertwining legend with history and in doing so approaching a kind of truth that can be hard for one or the other to achieve on its own. This seems to be a theme with Hugo, or at least a manifestation of his philosophy, by combining legend (story) with history we can approach a greater truth. But this is the first book of his I’ve read so I can’t make a strong statement on that, just a guess and intuition.

Hugo strikes me as a humanist who likely had deep sympathies for progressive ideals but he also fairly represents how high ideals can lead to the greatest crimes, with idealists leveraging the excuse of noble ends to justify execrable means. Sidestepping accountability and responsibility because one’s ideals are so noble and just. This critique is applied to both reactionaries and revolutionaries in this story as we see various characters in both camps guilty of this, some of whom stoop to the lowest basest most cynical self-serving justifications for their commitment of crimes against their fellow man. But there is nuance and subtlety, both in the writing and also the representation of the characters. Some characters are presented in a more favorable light than others, but never as pure black or white entities. The moral dilemmas the characters face are great, each individual is anchored by their various strain of idealism. These ideals get smashed and tested against the vortex of reality with crosscurrents tugging the individuals this way and that, each struggle further revealing inner character and nuance of each person...

I would recommend this book for two reasons: first off the magnificent quality of the writing and storytelling. 2ndly the fascinating historical backdrop and information in this book that seems to capture the essence and complexities of this particular historical period. And I could add a 3rd: experiencing Hugo and his sublime sensibility and ideas.

Cannot wait to read more. I’m thinking Les Mis, this will be a grand project, maybe later in the year I’ll try it out. I can’t read as fast in French or with quite as high a comprehension level as in English (but it is a fun challenge), so it will be a doubly huge undertaking if I end up going for it! But I think I’m falling in love with Hugo’s style. It is ornamented a certain way, grand and architectured to a high degree, so certainly not for everyone (I'm guessing he might be one of those love it or hate it kind of writers for people), but it appeals to me and my tastes!

Quote:

"L'homme peut, comme le ciel, avoir une sérénité noire; il suffit que quelque chose fasse en lui la nuit. La prêtrise avait fait la nuit dans Cimourdain. Qui a été prêtre l'est. Ce qui fait la nuit en nous peut laisser en nous les étoiles. Cimourdain était plein de vertus et de vérités, mais qui brillaient dans les ténèbres." -

“Liberdade , Igualdade e Fraternidade são dogmas de paz e harmonia. Para quê dar-lhes um aspeto assustador? Que pretendemos nós? Conquistar os povos para a república universal. Então não lhe façamos medo. Para que serve a intimidação? Como as aves, os povos não são atraídos pelo espantalho. Não se deve fazer o mal para fazer o bem. Não se derruba um trono para deixar o cadafalso de pé. Morte aos reis, e vida às nações. Abatamos as coroas, poupemos as cabeças. A revolução é a concórdia , não o medo. As ideias bondosas são mal servidas pelos homens inclementes.”

.

.

Victor Hugo é , desde que li o primeiro instante, um autor que me arrebata pela sua escrita humana, poderosa, incomparável e extremamente perspicaz. Sendo o quarto livro que já li do autor, a coragem e o esforço para descrever a beleza da sua escrita parecem-me sempre tão fracos. Victor Hugo encontra-se no pódio da literatura francesa, sendo para muitos até “o” supremo autor francês. O leitor encontrar-se-á sempre submerso na suas descrições tão pungentes das personagens, assim como dos cenários em que as mesmas se movem. Somos convidados a assistir a imagens tão realistas, dignas de pavor, de sofrimento e a detalhes que fazem da condição humana o que ela é. O drama é inesquecível e tocante.

.

.

O que também me cativa em Victor Hugo é a sua perceção da Revolução Francesa e do impacto que esta teve no povo. Em “Miseráveis" assistimos ao retrato dos condenados nas galés, às prostitutas, aos mendigos, aos padres, aos órfãos, num resumo do que é a miséria , a indignidade humana. Em “Notre-Dame de Paris”, Hugo faz um memorial da arte no seu esplendor e a sua decadência resultante das revoltas revolucionárias. Num mesmo tom, Victor Hugo levanta o esplendor da Revolução Francesa, mas também demonstra o caráter violento, inútil que a mesma teve.

.

.

Em “Noventa e três”, Hugo documenta o período sangrento da guerra entre os revolucionários e os monarquistas, assim como o culminar da sua guerra em 1793. Robespierre é inclusive descrito como um ser terrível, cheio de ambições, capaz de subjugar os outros para comandar as coisas a seu bel-prazer. O monárquico e o republicano nunca serão , na visão de Hugo e do leitor, o lado "certo".

.

O livro apresenta uma nota tão irónica e intemporal. Em todos os períodos históricos, em nome de uma ideia de mudança, da capacidade de tornarem as coisas melhores, não existe qualquer mudança no geral. O povo continuará a sofrer pilhagens, incêndios, violações ,assassinatos em massa e outras atrocidades tais. Só mudamos os trajes e os crimes. Mas, como Orwell enfatiza em “Quinta dos Animais”, no povo está a capacidade para afastar o governante na hora certa.

.

. -

من أجمل ما قرأت هذا العام !

-

ناو کلیمور چنان مرد که یک منتقم می میرد؛ ولی پیروزی او را نمی شناسد. انسان در جنگ با کشور خود قهرمان نیست

خیلی ناراحت کنندس که توی همه انقلاب ها تر و خشک باهم میسوزن -

فيكتور هوجو شاعر بالأساس ، فهو افضل من يصف مكان أو زمان

الرواية سياسية عن الحرب الأهلية بين الجمهوريه و الملكية

و ثلاثة أطفال و امهم فى خضم الحرب

" - من قتل زوجك ، الزرق أم البيض

- قتله رصاصة "

الرواية تعطيك فكرة شاملة عن معاناة الأنسان و ضميره فى حرب أهلية ، بين الانتصار للقضية و الانتصار للأنسانية -

Bene! Ora cosa faccio della mia vita?

-

Not easy, reviewing this. Parts of this book were stunning, absolutely beautiful - and then there were the rants. A lot of rants, a lot of lists of names - Hugo does this in his other books too, but he seemed to go overboard here. And the whole bit with Robespierre/Marat/Danton, I just couldn't make myself be interested. But then, the chapter "The Massacre of Saint Bartholomew" - where Hugo describes a day with the three toddlers on which the whole story hinges. Lovely, lovely, lovely. And all with the background of brutality and impending doom? Hugo knows just how to drive a knife into our hearts.

It's worth the read. Not my favorite of his works, by any means, but Hugo is a giant among writers and cannot be dismissed without loss to the reader.

"What a bird sings, a child prattles. It is the same hymn. An indistinct hymn, lisped, profound. The child, more than the bird, has the mysterious destiny of man before it. Hence, the melancholy feeling of those who listen, mingled with the joy of the little one who sings. The sublimest song to be heard on the earth is the lisping of the human soul on the lips of children. This confused whispering of a thought, which is yet only an instinct, contains a strange, unconscious appeal to eternal justice; perhaps it is a protestation on the threshold, before entering; a humble but poignant protestation; this ignorance smiling at the Infinite compromises all creation in the fate which is to be given to the feeble, helpless being. Misfortune, if it comes, will be an abuse of confidence.

The murmur of a child is more or less than speech; there are no notes, and yet it is a song; there are no syllables, and yet it is a language; this murmur had its beginning in heaven, and will not have its end on earth; it is before birth, and it will continue hereafter."

Hugo spends a fair bit of time describing the children's playing together, absolutely innocent and unaware that the room they have been locked in has been rigged to a fuse which will set alight a trail of tar... It's this kind of contrast - horror against innocence and beauty, that makes Hugo a master. -

I cannot believe I originally gave this book three out of five stars. What a humbug!! I have just listened to the audiobook again, and now starting it all over again....and I'm totally enthralled by it. I think I had expected something different from the outset. As rambling as Les Mis is in passages, yet there will never be another character such as Jean Valjean, and I think I was expecting it ~ but '93 is different, and rightly so. On first reading, certain passages (the ~ literally ~ loose cannon; the mother and children) seemed a bit random and disjointed, and neither was I expecting that it should so deal with the counterrevolution in the Vendee ~ too, as much as I Loved reading a scene containing Robespierre, Danton and Marat all together, it seemed to read more like an allegorical play at times, than a novel ("I am the man of the tenth of August"...etc).....What I didn't feel at the first reading, and which I do now, is that it really is indeed like an Allegory of the Revolution, and especially of that tumultuous year, 1793 ~ the year that Marat was to be murdered and the year of Terror to begin. Hugo is trying to grapple with both the beauty and hideousness of the revolution, as embodied in three characters: the counterrevolutionary Marquis de Lantenac (monarchy; the old regime); Cimourdain (the ruthless justice of the Revolution); and Gauvain (the nobler and purer spirit of the Revolution; the ideal). But I need to stop here....I'll just say again that it seems to me one of those books that grow more interesting and beautiful over time...and, at the very least, food for thought in it's portrait of revolution, and in those truths which soar above an earthly justice.

-

ফরাসি বিপ্লব নিয়ে বই কম পড়ি নাই। Dickens এর A Tale of Two Cities থেকে শুরু করে,

The Scarlet Pimpernel, A Place of Greater Safety সহ অনেক বই পড়েছি।এই পর্যন্ত সবচেয়ে ভাল লেগেছে এই বইটি।কারন এই বইটিতে ফরাসি বিপ্লব এর প্রকৃত ভয়াবহতা ফুটে উঠেছে।

বইয়ের নামের সাথে মিল রেখে বইয়ের পটভূমি ১৭৯৩ সালের।ফরাসি বিপ্লব তখন চরম রূপ ধারন করেছে।রাজাসহ অন্যান্য অভিজাতগণ এর মাথা গিলোটিনে কাটা পড়েছে।দেশজুড়ে গৃহযুদ্ধ ছড়িয়ে পরেছে।এই পরিস্থিতেতে গল্পের শুরু হয়।

দুর্ধর্ষ রাজতন্ত্রী মাহখি দু লতেনাক এর গল্প এটি।তিনিই রাজতন্ত্রীদের প্রধান ভরসা।অন্যদিকে তাকে যে কোন মূ্ল্যে ঠেকাতে ছুটে এসেছে বিপ্লবী সিমুরদা এবং গুভা।আর সবকিছুর সাথে জড়িয়ে গেছে ফ্লেশা নামের এক তরুণী।

স্বাধীনতা,আদর্শ,বিপ্লব এবং আত্মত্যাগের অসামান্য একটি কাহিনি।যারা ফরাসি ফরাসি বিপ্লব নিয়ে আগ্রহী ,তাদের জন্য চমৎকার একটি বই।