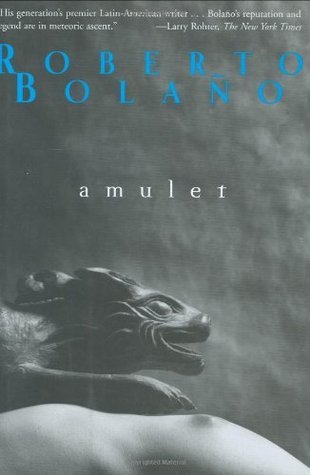

| Title | : | Amulet |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0811216640 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780811216647 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 192 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1999 |

Amulet Reviews

-

Es posible que no sea lo mejor de Bolaño. Sin embargo, el atractivo y el encanto con el que el autor dota a su personaje, Auxilio Lacouture, convirtieron la lectura para mí en puro gozo.

Auxilio es el precioso homenaje que Bolaño hace a Alcira Soust Scaffo, poeta uruguaya que sobrevivió a la ocupación por el ejército mejicano de la Ciudad Universitaria gracias a que pudo esconderse en los baños de la UNAM y permanecer en ellos durante doce días con sus doce noches hasta ser rescatada medio muerta.

Este suceso ignominioso de la historia mexicana es el centro sobre el que gravita todo el “delirio aterrorizado” que es la novela, tal y como tan acertadamente la califica Rodrigo Fresán, aunque lo que la hace inolvidable es la voz de Auxilio, la libertad que de ella emana, su delicioso juego con las palabras que es una verdadera fiesta del lenguaje que me trajo a la mente no pocas veces la genial y exuberante novela de Fernando del Paso, Palinuro de México, la cual también tiene como eje central la masacre de la Plaza de Tlatelolco, pero sobre todo me la recordó por párrafos como este:“El tiempo o no se detiene nunca o está detenido desde siempre, digamos entonces que el contínuum del tiempo sufre un escalofrío, o digamos que el tiempo abre las patotas y se agacha y mete la cabeza entre las ingles y me mira al revés, unos centímetros tan sólo más abajo del culo, y me guiña un ojo loco, o digamos que la luna llena o creciente o la oscura luna menguante del DF vuelve a deslizarse por las baldosas del lavabo de mujeres de la cuarta planta de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, o digamos que se levanta un silencio de velatorio en el café Quito y que sólo escucho los murmullos de los fantasmas de la corte de Lilian Serpas y que no sé, una vez más, si estoy en el 68 o en el 74 o en el 80 o si de una vez por todas me estoy aproximando como la sombra de un barco naufragado al dichoso año 2000 que no veré.”

Desde esos lavabos, Auxilio anda pendiente de cado sonido, de cada sombra, intentando exorcizar el horror con esa luna que se refleja en las baldosas y le permite leer poemas de Pedro Garfias, con esa luna que salta de baldosa en baldosa y las derrite “hasta abrir un boquete por donde pasan imágenes, películas que hablan de nosotros y de nuestras lecturas y del futuro rápido como la luz y que no veremos”. Auxilio recuerda, reinventa y recrea un pasado, un presente y un futuro, sin atenerse a ningún orden, sin trama a la que ceñirse, sin tema que no pueda tocarse, sin poeta, real o ficticio, que no pueda imaginar, sin encuentro en bares, calles y salones que no pueda producirse. Auxilio siente y expresa un amor profundo por la poesía y por los poetas y ella misma se convierte en poeta en el recuerdo de personas y episodios, de esas personas y episodios que no deben caer en el olvido, porque hay una responsabilidad del recuerdo, una obligación contra el olvido que entierra a personas y episodios, que, como los libros, son presas fáciles del polvo. Lo exige toda una generación de poetas y no poetas que asistieron al final del sueño revolucionario.“Será una historia policíaca, un relato de serie negra y de terror. Pero no lo parecerá. No lo parecerá porque soy yo la que lo cuenta.”

Y hay que agradecerle y mucho a Bolaño la creación de esta voz encantadora que cuenta, esta Auxilio tan cercana a la Maga de Cortázar que siente pero no sabe, que ignora el porqué de la tristeza que desprende un simple florero pero es capaz de sentir el infierno que se encierra en su boca y llorar y casi desmayarse. Asidua a las mil tertulias de poetas es incapaz de entender el glílico que allí se habla, abierta a todos para los que siempre tiene cien palabras o mil, vagabunda por el DF convertida en murciélago o duende. Auxilio la testigo, Auxilio la memoria, Auxilio visionaria del futuro y visionaria también del pasado, Auxilio madre de la poesía mexicana, Auxilio la que se nutre de literatura hasta quedar desdentada y triste, la poseedora de la poesía, del canto que protege, del canto que es nuestro amuleto. -

History is like a horror story.

The student youth of Mexico raised their fists in protest during the summer and fall of 1968, marching against the government towards the violent climax of the

Tlatelolco Massacre on October 2nd. ¹ Student demonstrations were organized in response to the killings of several students by the police called in to repress a fight between gang members of two rival schools—the Mexican National Autonomous University (UNAM) and National Politechnical Institute (IPN)—and were further aggravated by the upcoming summer Olympics taking place in Mexico City. The Olympic Committee, headed by an American, chose Mexico as the first third-world country to host an Olympic event, and protestors saw this as an attempt to portray Mexico as a country stabilized by American support and financial backing. Protestors took to the streets shouting ‘We Don't Want Olympic Games, We Want a Revolution!’ Roberto Bolaño’s slim, yet satisfying, Amulet has as its centerpiece the Mexican army occupation of UNAM, using the violent event as a nucleus around which narrator Auxilio Lacouture’s life events orbit. Finding herself trapped in the UNAM bathroom during the occupation, a subtle yet monumental act of resistance, Auxilio becomes unstuck in time, narrating events both past, present and future, yet always returning to the moonlight reflecting off the tiles of the lonely bathroom floor. Through pure poetic ecstasy, Bolaño uses Auxilio’s beautiful mind and perspective to brilliantly juxtapose seemingly disparate elements in order to paint a unified and emotionally charged portrait of the struggles, sorrows and strife of the Latin American people.

Student demonstration, August 27th, 1968

‘I could say I am the mother of Mexican poetry, Auxilio says on the opening page, ‘but I better not. I know all the poets and all the poets know me.’ Drifting in extreme poverty through the streets of Mexico City like so many others, Auxilio is a glorious soul that finds odd jobs at the university to earn her keep while spending her nights in drunken sublimity with the young Mexican poets, such as the authors alter-ego, Arturo Belano, caring for them as a mother while being shamelessly enraptured by their poetry. Auxilio has a rare gift of seeing the events of the world, past and future, unfold before her eyes, unlocked during her isolation in the UNAM bathroom, but with this gift comes great costs. It would be easy to dismiss her as crazy, a woman missing teeth (‘I lost my teeth on the alter of human sacrifice’) and crying at the words of people half her age before leaving the bars without paying, yet that would be a grave misunderstanding and would deny oneself an illuminating look into her heart and soul.I never paid, or hardly ever. I was the one who could see into the past and those who can see into the past never pay. But I could also see into the future and vision of that kind comes at a high price: life, sometimes, or sanity. So I figured I was paying, night after forgotten night, though nobody realized it; I was paying for everyone’s round, the kids who would be poets and those who never would.

I like to believe that one of the many gifts of literature is to cultivate a more open-minded view and to learn acceptance of others. Auxilio must face the horrors of history, of existence, in a way others cannot, and must travel to the vicious depths of her soul that most minds form a wall to protect themselves from having to journey into. Like a snake that unhinges its jaw to swallow a large meal, Auxilio must unhinge her mind—at least by the common socially accepted, or clinical, standards²in order to swallow such enormous thoughts and burdensome truths. She witnesses the pains and poverty of others, and is charged with the task of putting it all together to witness the birth of History and document it across the ages.The birth of History can’t wait, and if we arrive late you won’t see anything, only ruins and smoke, an empty landscape, and you’ll be alone again forever even if you go out and get drunk with your poet friends every night

Bolaño possessed an incredible gift for organizing seemingly unrelated events into a unified message. Auxilio’s skipping across time bears witness to many different characters and subtly probes into their hearts, making Amulet almost feel like a collection of short stories, with them all orbiting around one narrator. Yet, somehow through the juxtaposition, Bolaño manages to make each story mesh, creating a space between each idea where the reader’s mind will occupy and abstractly connect each element, each theme, into one larger, all-encompassing image. These are stories of poverty, resilience, heartbreak, rebellion, bravery and even an investigation into the story of

Erigone and

Orestes. The conflict between students and government is also juxtaposed with the overthrowing of Allende in Chile, in which Belano plays a role. While no connection is never made overt, the themes of conflict and revolution are enough to give the reader a sense of the violence haunting Bolaño . What is most impressive and satisfying, however, is the way Bolaño orchestrates a world where literature is of the utmost importance, giving meaning and validation to the lives of those who give meaning through its application to the sights and sounds of the horror show of History playing out around them.

Much in the ways Auxilio binds the lives of those around her into one common, driving force, Amulet serves to bind together the oeuvre of its author. As

Distant Star is the elaboration of the final story in

Nazi Literature in the Americas, Amulet expands on Auxilio’s small, but unforgettable account in

The Savage Detectives. While Amulet may be a minor work, it plays a key role in the Bolaño universe, expanding on the themes that constitute the life-giving roots of his work. The idea that violence plagues Latin America through all eternity is glimpsed, even connecting itself to his magnum opus

2666 through a hallucinatory passage as Auxilio follows Belano towards a potentially deadly confrontation:Then we walked down the Avenida Guerrero; they weren’t stepping so lightly any more, and I wasn’t feeling too enthusiastic either. Guerrero, at that time of night, is more like a cemetery than an avenue, not a cemetery in 1974 or in 1968, or 1975, but a cemetery in the year 2666, a forgotten cemetery under the eyelid of a corpse or an unborn child, bathed in the dispassionate fluids of an eye that tried so hard to forget one particular thing that it ended up forgetting everything else.

This intertextuality is one of the many reasons that it is hard to go long without returning to the poetic pages of a Bolaño book, creating a world that seems to come alive through repeat characters.

Short, yet overflowing with passages of sheer beauty reminiscent of Bolaño’s prose poems that are sure to drain your pen dry underlining each gem, Amulet is a wonderful trip through horrific and melancholy events. Auxilio may only play a small role in the uprisings, yet her small role forever transfixes her into mythological magnitude in history, becoming a beacon of hope and a symbol of fortitude for the weak and weary to seek comfort and redemption. The final pages are the most haunting, culminating all the sorrows and struggles into a song of revolution that will live on regardless of the body count at the oppressive hands of both the army and history. Similarly, while Bolaño may have passed, his voice lives on. It is certainly a voice worth listening to.

4/5

‘ I'll tell you, my friends: it's all in the nerves. The nerves that tense and relax as you approach the edges of companionship and love. The razor-sharp edges of companionship and love.’

¹The following history of the 1968 student revolution is paraphrased from the article

October 2nd is Not Forgotten.

²As discussed in Machado De Assis’

The Alienist, we are all uniquely wired (or, perhaps, uniquely weird), and who is really to say what constitutes sanity. Understandably there must be clinical standards, I’m not here to disparage the psychological community in any way, however, Auxilio is a wonderful literary example of how we often write off others without truly attempting to understand them and see the world through their eyes. By dismissing her as crazy, you lose the opportunity to unlock the world and learn through her. Laziness is similar, and often dismissing someone as lazy is actually the lazy way out; even what appears as laziness is a highly complex set of emotions and actions that offer deeper insights into a person. Not that this is a universal law, but hopefully you get the point. I’m moralizing now, which makes me extraordinarily uncomfortable, so I’ll conclude by reiterating that literature, and characters like Auxilio, plead that we try harder to understand and accept one another instead of casting one another aside through negatively connotative dismissals.

‘I decided to tell the truth even if it meant being pointed at.’ -

Amulet focuses on one of the minor characters in The Savage Detectives, Uruguayan poet Auxilio Lacouture, 'the mother of all young Mexican poets'. When the army invades the campus of the National Autonomous University of Mexico in 1968, Auxilio happens to be in the women's toilets, and fearing she might face arrest or worse, she ends up hiding in the bathroom for thirteen days, drinking tap water and chewing scraps of toilet paper to survive. She soon starts hallucinating, and this slim novel (only 120-odd pages), is the record of her meandering mind, shifting from memories to prophecies in Bolaño's distinctive style - inventive, quirky and entertaining. The picaresque episodes are strewn with mantra-like repetitions and occasionally go over the top - but just at the point where I was ready to berate Bolaño for self-indulgence, he brought everything together in a moving finale, a real tour de force. Highly recommended.

On a personal note, this is the second book I've ever read in Spanish (I've read The Savage Detectives in translation). I'm slowly getting there! -

Roberto Bolano – Amulet

Just a moment while I’m trying to dry myself after this dive into a sea of words. A sea in which you’re in and which is in you at the same time. A sea sometimes calm (but never too calm) and other times swirling with fluctuating intensity, roaring and crashing, never allowing even a glimpse of land. Reading Amulet is like taking a nauseous, dreamy ride on a rollercoaster with a bottle of vodka in your hand. The narrator calls herself the mother of Mexican poetry. To me, she is a symbol of many things which I dare not name. She finds herself trapped in a bathroom stall during the army occupation of the Mexican National Autonomous University and there she starts recollecting moments from the past as well as the future. Memories float and grow around her like a cocoon which protects and nourishes all that's heroic and worth saving in this rapidly changing world. Mesmerizing and rousing at the same time, this little book begs for a re-read. As a matter of fact, it begs to be taken out of the shelf every once in a while for a quick read through random pages. I wonder what this will feel like.

Not quite dry enough but who am I kidding? Something tells me Bolano’s sea is one you never stop carrying inside you. -

ذكريات مبعثرة وغير مرتبة زمنيا في حياة أوكسيليو لاكوتور

تتذكرها وهي مختبأة في إحدى كليات جامعة المكسيك

بعد ��قتحام القوات الحكومية للجامعة في سبتمبر 1968 لفض المظاهرات واعتقال الطلاب والأساتذة

تحكي عن السياسة في أمريكا اللاتينية, وعن الأصدقاء من الشعراء والأدباء في المكسيك

ومنهم الشاعر الشاب ارتوريتو بيلانو الذي تتشابه أحداث حياته مع روبرتو بولانيو الكاتب

سرد ساخر أحيانا فيه شيء من الهذيان ما بين الذكريات والأحلام

يكتب بولانيو عن معاناة شباب القارة اللاتينية من الصراعات السياسية والديكتاتوريات

ويحتفي بالكثير من المبدعين في أمريكا اللاتينية من الشعراء والكُتاب والفنانين -

When Only a Wedge Will Do

I read this because I’m a lazy cheapskate.

I bought it for $5 (reduced from $50) in a recent Borders sale.

But I was looking for a relatively short wedgie between larger undertakings, the next of which will be Haruki Murakami’s “1Q84”.

At 184 pages, it’s more of a novella than a novel (although I’ve never really understood or cared much for the distinction).

What’s important for me is how much the author put into those pages and how much we the readers get out of them.

As I write this, I’m hovering between rating it five or four stars. I wonder what I’ll manage to persuade myself.

Galvanised Irony

For each generation, there is sometimes (not always) an event that seems to either polarize or galvanise people.

It could horrify or unite them.

It could symbolize conflicts or trends that might not yet have become apparent and only become obvious retrospectively.

In 1937, it could have been the bombing of Guernica (which was depicted in Picasso’s famous work of cubism).

In 1945, it could have been the bombing of Dresden.

In 1956, it could have been the invasion of Hungary.

In 1968, it could have been the invasion of Czechoslovakia.

In 2001, it could have been the collapse of the Twin Towers.

Since the advent of TV and 24 hour news, there are so many of these events that you could almost argue that none stands out from the others.

Europe 1968

On 22 March, 1968, a small group of students, poets and musicians occupied an administration building at the University of Paris.

After the Police were called, the group left the building peacefully.

However, subsequent conflicts resulted in the closure of the University on 2 May.

Demonstrations, protests, strikes and riots occurred over Paris throughout May, eventually petering out in June and July.

On the evening of 20 August, 1968, the armed forces of the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia.

Mexico 1968

Meanwhile, on 12 October, 1968, the athletes of the world were to gather in Mexico City for the Games of the XIX Olympiad.

It was to be the first time the Summer Olympics would ever be held outside Europe, the United States or Australia.

The Mexican Government treated the Olympics as a unique opportunity to showcase the country to the world.

It spent US$150M (US$7.5BN in today’s terms) on the preparation for the games, money that the basically Third World country could ill afford.

After a number of student protests against government oppression, there was a peaceful protest of 50,000 students at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (“UNAM”) on 1 August, 1968.

The fact that such a huge protest was peaceful convinced the public that the protesters were not just violent gangs or rabble-rousers.

However, in mid-September, the President of Mexico ordered the Army to occupy the UNAM Campus.

Many staff and teachers were beaten and arrested.

Then, on 2 October (just ten days before the Opening Ceremony), around 10,000 university and high school students assembled in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco.

What followed was a massacre by the Police and Army in which between 30 and 1,000 protesters and bystanders were killed (depending on who you believe).

The Plaza is closed off by buildings on three sides.

The Government basically closed off the fourth side and started shooting.

Thirteen Days in a Cubicle

“Amulet” takes place over thirteen days and twelve nights from the eighteenth to the thirtieth of September.

Auxilio Lacouture is a Uruguayan national who lives in Mexico City.

She loves poetry and might even be a poet herself.

She works part-time at UNAM and cleans the apartments of a number of her favourite poets.

“I am a friend to all Mexicans. I could say I am the mother of Mexican poetry, but I better not. I know all the poets and all the poets know me.”

On 18 September, she finds herself in the middle of the whirlwind that blows through Mexico City:

“I could say one mother of a zephyr is blowing down the centuries, but I better not.”

At the very point the Government evacuates the campus, she is sitting in a cubicle in the women’s bathroom on the fourth floor of the building that houses the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature.

She evades capture and remains in the bathroom for the duration of the novel, dreaming and reading her book of poetry, while outside the campus is guarded by the Army.

“Amulet” could be an almost stream of consciousness record of her musings over the thirteen days, only it’s more accurate to describe it as a river of conscience.

It concerns political issues, but it’s not an ideological tract.

“This is going to be a horror story. A story of murder, detection and horror. But it won’t appear to be, for the simple reason that I am the teller. Told by me, it won’t seem like that. Although, in fact, it’s the story of a terrible crime.”

It’s easy to read, its economical and eloquent, but most importantly Bolano's prose has an hypnotic droning beauty that suits the judgment of history on an isolated, but all too frequent, outbreak of evil .

Heroes of the Oppression

The heroes of the novel are the poets and painters.

They are latter day gods.

Their youth, curiosity and expressiveness embody the best that civilization has to offer.

They are its life force.

While poets write and recite, while artists wield their brushes, society has a heartbeat.

When they stop, life stops, civilization stops.

“The dark night of the soul advances through the streets of Mexico City sweeping all before it. And now it is rare to hear singing, where once everything was a song. The dust cloud reduces everything to dust. First the poets, then love, then, when it seems to be sated and about to disperse, the cloud returns to hang high over your city or your mind, with a mysterious air that means it has no intention of moving.”

Auxilio is the mother of the poets, their audience, their protector, their sustenance.

This responsibility has to be borne by a woman, a mother who cares.

She draws her own sustenance from other women, such as the Catalan painter Remedios Varo and the Mexican poet, Lilian Serpas, of whom she says:

“I know she that she has seen many bad things, the ascension of the devil, the unstoppable procession of termites climbing the Tree of Life, the conflict between the Enlightenment and the Shadow or the Empire or the Kingdom of Order, which are all proper names for the irrational stain that is bent on turning us into beasts or robots, and which has been fighting against the Enlightenment since the beginning of time...”

Descent into the Maelstrom

In the last chapter, Auxilio decides to leave the building, to “come down from the mountains”, where she has exiled herself:

“I decided not to starve to death in the women’s bathroom. I decided not to go crazy. I decided not to become a beggar. I decided to tell the truth even if it meant being pointed at.”

She sees two birds singing in a tree.

They watch, as a cloud sweeps across a broad field in the direction of an abyss.

At first, she thinks that it is the cloud casting a dark shadow over the valley.

Then she realises it is “a multitude of young people, an interminable legion of young people on the march to somewhere…I was too far away to see their faces. But I saw them. I don’t know if they were creatures of flesh and blood or ghosts. But I saw them...They were probably ghosts.”

Then she realises that they were singing, “singing and heading for the abyss”.

It was a “barely audible song, a song of war and love, because although the children were clearly marching to war, the way they marched recalled the superb, theatrical attitudes of love…and although the song that I heard was about war, about the heroic deeds of a whole generation of young Latin Americans led to sacrifice, I knew that above and beyond all, it was about courage and mirrors, desire and pleasure.”

Onward Questioning Soldiers

For every generation, there are some who march and sing, there are some who resist oppression, while the rest of us take the path of least resistance.

There are some of us who hide in cubicles for thirteen days, yet can still find it in themselves to admire cubists.

Hundreds, maybe a thousand died, that day at Tlatelolco.

“Amulet” is Roberto Bolano’s tribute and thank you to them.

It is also a recording of their song, an amulet that will hopefully bring the rest of us, the survivors, another generation of children and young people, good luck and protection.

Olympic Postscript

In the 200m medal award ceremony, African-American athletes Tommie Smith (gold) and John Carlos (bronze) raised their black-gloved fists as a symbol of "Black Power".

The Australian, Peter Norman (silver), wore an American "civil rights" badge as support for them on the podium.

Avery Brundage, President of the International Olympic Committee, firmly believed that politics should have no role in the Olympics.

In the short term, Smith and Carlos were suspended from the U.S. team and banned from the Olympic Village.

In the long term, the IOC banned Smith and Carlos from the Olympic Games for life, and Norman was omitted from the Australian 1972 Olympic team.

This review is dedicated to people who resisted oppression when it would have been personally safer and easier not to.

October 7, 2011 -

"This story breaks away from its box."

Roberto Bolaño destroys the reader’s preexisting expectations, as what the reader sees is rarely what he gets. I’ve only previously read "Los Detectives Salvajes" before, and was immediately happy to see that this was an extension of that novel, or, more accurately, it works as a companion piece. I love this kind of stuff! Complimentary works are... extremely difficult to pull off, as one bad novel might pollute the other one. (Take for instance the Hannibal Lecter quadrilogy: Thomas Harris’ first Lecter tale was the superb Red Dragon, which then catapulted the villain to fame in The Silence of the Lambs-- but years later Hannibal fumbled, becoming a cataclysmic literary disaster, followed by the last gasp in those grey ashes, Hannibal Rising.) But in this case, both novels are as different in style as could be, though perhaps not different in theme. Bolaño chronicles an all-but-forgotten literary movement that occurred almost half a century ago at the epicenter of Mexico City. He describes a bohemian existence of poets and artists and Auxilio’s inner trek through memory and even through the to-be-lived future paints a vivid portrait of the members of this artistic wave.

Surrealism has a better hold on Amulet than its companion novel. The Savage Detective is epic and wide-spanning--many voices are given chance to chronicle that bright but doomed time, but Amulet centers around Auxilio Laucouture. In Amulet you hear the narrative of a ghost. The heroine, mother to all Mexican poets, part Rapunzel, part deranged pariah (think of the woman from The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman), atop her terrible tower experiences a time warp, and vacillates in examining scenes from her past and her future. Experiences she is yet to have are seen, in true metaphysical oracle style. Her distance from all action occurring in the university and the city gives her the advantage to reach true inner contemplation, to such a degree (no doubt hunger being a driving force) that she admits: “I started thinking about my past as if I was thinking about my present, future and past, all mixed together and dormant in the one tepid egg, the enormous egg of some inner bird (an archaeopteryx?) nestled on a bed of smoking rubble.” The character is an obvious spectator (here is the connection to many other novels that deal with consciousness). Again, in doing nothing (��Stay here, Auxilio, you don’t have to be in that movie; if they want to make you play a role, they can damn well come & find you”) she becomes the perfect candidate to give a form to the narrative, though, like mentioned before, this “horror story” breaks from its set parameters.

We are hearing the story directly from Auxilio herself. There is enough evidence of a mumbling, sad, imperfect human directing all of this, & it is because the magic (for instance: the surreal scene inside the antechamber of the King of the Rent Boys in Colonia Guerrero, or the two visionaries [Auxilio and Carlos Coffeen Serpas] coming face-to-face) is filtered through a poetic voice that the effects go unquestioned. Being in the “nun’s cell [Auxilio] never had” makes times, scenes, and emotions transitory: they bleed into each other.

Whereas The Savage Detectives follows a clear (you can almost say predestined) path, Amulet promises things which are then delivered, albeit in ambiguous ways. I was expecting, for instance, a cinematic rescue from the bathroom stalls. A closure to the historic events of the army’s invasion of el DF in 1968. Instead, the “Mother of Mexican Poetry” gives us her prophecies which describes a fun flight of poetic fancy, but also includes her harrowing, apocalyptic vision of “the prettiest children of Latin America, the ill-fed and the well-fed children, those who had everything and those who had nothing, such a beautiful song it is, issuing from their lips, and how beautiful they were, such beauty, although they were marching deathward." -

ما درماندگان میخواستیم فریاد سر دهیم، لیک فریادرسی نبود. پترونیوس. صفحهی ۸ کتاب

شاید آنچه مرا به سفر واداشت دیوانگی بود. میتوانست دیوانگی هم باشد. به گمان من که دلیلش فرهنگ بود. البته فرهنگ گاه دیوانگی است و گاه دربرگیرندهی دیوانگی. صفحه ۱۱ کتاب

آدمی تن به خطر میدهد. این یک حقیقت محض است. آدمی تن به خطر میدهد و بازیچهی دست سرنوشت میشود، حتی در نامحتملترین مکانها. صفحهی ۱۵ کتاب

معتقدم زندگی پر است از چیزهای کوچک معما وار، رخدادهایی که همواره مترصد تماس با پوست یا نگاهمان هستند تا بدل به زنجیرهای از پیامدها شوند که تنها با عبور از منشور زمان چهره عیان میکنند و البته هول و هراس برمیانگیزند. صفحهی ۲۸ کتاب

عشق چنین است، زبان عامیانه چنین است، خیابانها چنینند، سوناتها چنینند، آسمان پنج صبح چنین است. اما رفاقت نه. تو با رفیق تنها نیستی. صفحهی ۵۹ کتاب

همه ما عشق کهنهای داریم که هر وقت دیگر چیزی برای گفتن نمیماند، پایش را وسط میکشیم. صفحهی ۱۲۹ کتاب

-

Okuyucu olarak çok hassas bir dönemimdeyim. İçi boş, basit ve ya tam tersi çok ağdalı şeylerden sıkılıveriyorum. Edebi üsluptan çok anlatılan şeyin niteliği önemli bu aralar. O yüzden laf kalabalığı yapan yazarların eserleri elimde büyüyor, bitmiyor.

Bolano bu konuda tam olarak otorite. Bir konu bu kadar güzel, sade, özel anlatılabilir. Bir sayfayı iki kere okuduğum oldu çünkü olayı anlatma, metaforize etme şekline hayran kaldım. Kelime kelimesine okuyup, her dakikasını kavramaya çalıştığım bir eser oldu. Hiç laf kalabalığı yapmadan ama edebiyattın da dibine vurmayı ihmal etmeden yazılmış süper bir kitap.

10/8 -

"Amajlija" je dovoljno kratka da se pročita u cugu i dovoljno hipnotička da tako i treba da se pročita. I mnogo znači - hoću reći, meni znači - što Bolanjo piše tako kako piše, od prve rečenice navali na čitaoca kao teška konjica u Aleksandru Nevskom i zahteva njegovu celokupnu pažnju.

Strukturno je roman pomalo nezgodan (bar za one koji vole klasičan zaplet) jer se ne vidi odmah da je koncipiran kao niz ulančanih i ne sasvim čvrsto povezanih celina koje spaja samo pripovedačica (ali s druge strane, prvih pola strane vam je sasvim dovoljno upozorenje i ko ne odustane sam je kriv). Same celine, opet, nisu prave celine nego onako... delovi bolanjovskog opusa koji mogu da se prišiju za sve ostale delove koje je za života uspeo da napiše i povremeno baš deluju kao da se ne mogu razumeti bez još barem dve-tri Bolanjove knjige. Ali pripovedačica Auksilio je tako fenomenalno istovremeno životan i nadrealan lik da mu je teško naći para i već samo zbog uživanja u njenom glasu vredi ovo pročitati.

Šta znam, posle 2666 (koji me je teško impresionirao) Amajlija me uopšte nije razočarala, samo je... kratka. Što verovatno znači da ću u potragu za ostalim prevedenim Bolanjovim knjigama. -

“I am in the women’s bathroom in the faculty building and I can see the future, I said, in a soprano voice, as if I were being coy.

I know that said the dreamy voice, I know that. You start making your prophecies and I’ll note them down.”

I found this book very difficult to come to terms with at times which is based around the year 1968 in Mexico City, be it the future, the past or the present which are all thrown in for good measure to confuse a poor literary individual such as myself.

The narrator, Auxilio Lacouture, a Uruguayan woman, is a poet, and a very unusual woman, who moved to Latin American’s biggest city, Mexico City in the 1960s. She “turned up at the apartments of Léon Felipe and Petro Garfias” where she offered to clean their apartments by dusting their books and sweeping their floors, etc.”. This is a very unusual, slightly masculine woman with, “blue eyes, blond hair going gray, cut in a bob, long, thin face, lined forehead”, who can examine objects over and over again, such as the vase and books mentioned in one of the apartments she is taking care of at the beginning of the book.

Just to add character to her face, her four front teeth are missing. She couldn’t afford to have these replaced at the time and then lost the inclination to do so. And yet obviously this did bother her because whenever she laughed, she always covered her face with one of her hands. Did people know she had four teeth missing? Well if they did, they were not letting on. She also reminded me of being a kind of literary groupie, as she loved to follow the poets in the bars, and cafés of the university, and also to enjoy the night life where she was known as the “Mother of Mexican Poetry.”

Apart from these poets, Auxilio intrigued me with the three women she became friendly with. There is the young philosopher Elena who was in love with an Italian, Paolo, who was purely in Mexico so that he could obtain a visa to go and interview Castro in Cuba; the exiled Catalan painter Remedios Varo, and Lilian Serpas, a poet, who once slept with Che Guevara, with an unusual son called Coffeen who intrigued Auxilio with his tales on Erigone and Orestes.

The Faculty of Philosophy and Literature, in the Mexican National Autonomous University where Auxilio worked at the time, shows an individual, a survivor, constantly on the move, staying with people, losing her possessions, such as her books and clothes; with uncertain working habits but who was also living with this incredible imagination. I thought it was amazing that she could survive a week without spending a peso. Perhaps I’m living in the wrong country because money melts here.

Auxilio knew that something horrific was going to happen during the course of 1968. She made prophecies. She was in the women’s bathroom of the faculty building on the fourth floor she thinks, she wasn’t sure. Her memories and thoughts are vague as to when they actually happened. She had a propensity for reading in bathrooms (I always thought that was a male trait) as women tend to dash in and out.

When this horrific act happened “she saw it all and yet she didn’t see a thing”; “she heard “a noise in her soul”. She stayed in the “stall” and didn’t come out until everyone had left. The famous date was 18 September when the university was taken over by the army, who arrested and killed students indiscriminately. Many more people though were killed in the Tlatelolco massacre on 2 October 1968 in the” Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City. The violence occurred ten days before the 1968 Summer Olympics celebrations in Mexico City.”

I couldn’t really handle the first couple of chapters at all but then I discovered the mantra of the bathroom shown above and I managed to settle to a certain extent in the unusual rhythm of this novella.

Amongst Auxilio’s odd prophecies were:

“For Marcel Proust, a desperate and prolonged period of oblivion shall begin in the year 2033. Ezra Pound shall disappear from certain libraries in the year 2089….César Vallejo shall be read underground in the year 2045. Jorge Luis Borges shall be read underground in under underground in the year 2045.”

Why would Bolaño want to repeat the last two sentences with the same year? For what purpose? The years that were given? Were these purely fiction or is there some significance here that I’m unaware of?

And as for the statement, “Virginia Woolf shall be reincarnated as an Argentinean fiction writer in the year 2076”? Remarkable how she has come into the equation.

This is an extraordinary book with a writing style that I have never encountered before. It was purely a monologue and it did tend to ramble and repeat itself at times. Did I like it? Well, really I’m not too sure.

Yet again, I was seduced by the title and by an unknown author (to me anyway) but who receives amazing reviews. So going into “sheep mode” I acquired this “taster” of a book.

I could even see the parallels in this book with the May 1968 events in France, which was a volatile period of civil unrest, general strikes and the occupation of factories and universities across the country. These lasted a far longer period and have had serious repercussions on both the French mentality and society, and also upon their economy that is still felt up to the present day. For you see, they continue to remember that the worm can still turn.

There’s a dreamlike quality about this writing which I found confusing at times, especially Auxilio’s “mental” visits, I guess, into the mountains when everything becomes very strange and completely beyond me. Characters pass confusedly throughout the book like ghosts. Parts are brilliant with spell-binding prose, others are brilliantly-depressing, some are magical and yet there are also some very boring long-winded sections that were extraneous but all in all, how does one rate this work? I don’t know in all honesty and so I’ll go middle of the road until I can read another book by the author to be able to compare my own confused thoughts. Which book to follow up with? Now that’s the ongoing dilemma.

And finally with the idealistic young Latin Americans who came to maturity in the 1970s, I could understand the meaning of the title with the last words of the novel when I read: “And that song is our amulet”.

And what is that you may wonder? Well, you’ll have to read the book. -

I want to give this book five stars, but since I didn't give Savage Detectives or 2666 five stars I feel it's only fitting to give this four stars.

A lot of people gush about Bolano, so much that it's enough to turn off other people from him. That said, there are quite a few people who really dislike Bolano mostly because hipster's and others were all over him (but were they really? It seems to me like Bolano-mania is over and now it's safe to come out and read his work in peace, but I could be wrong).

Bolano is not as good as the hype surrounding him says he is, but he's also so much better than his detractors say he is.

When I bought this book for 49 cents at the Salvation Army around the corner from my apartment I went from being elated at such a great find to annoyed when I got home and read what the book was about. It is the story of the woman who for 13 days is trapped in the bathroom of a university while the army takes it over. She is symbolic of withstanding the assault of the military on the university and all of that. Her story is one of the many in Savage Detectives. I was kind of annoyed that I thought I had just bought a book that would take her story and just make it longer, maybe give more details about sitting in the bathroom.

I was wrong to be annoyed.

What I take this book to be about: the moment (well 13 days) she is trapped in this bathroom is expounded on, but as a singularity that encompasses the past and future of her experience of moving from a mere spectator of history to meeting it head on. Why Bolano chose this method of telling her story, I'm not quite sure. One would think it would be easier to say ok, there was this lady in the middle of her life who was trapped in a bathroom, here is what happened before and after; instead of presenting her life through a prism of memories of events that had and hadn't already happened (But if that was the case, then would be no way of incorporating her beautiful prophecies into the story).

Why I heart Bolano, and why you should too.

He makes literature at least seem important. Because he writes with such a love for literature, and writes from a time and place where writing was still something important enough that people lived and died for it. That even if in the long run maybe it didn't make an ounce of difference, people on both sides of the political spectrum believed that it mattered enough that they would risk their lives to be writers and poets, and on the other side of the spectrum people would expend energy to silence these writers and poets, exile them and be fearful of what they might stir up.

It's not even necessarily political, it's about living for capital L Literature, because there is something about it that makes one feel the need to risk ones life for it, or maybe not risk ones life but live ones life for it. Maybe my enjoyment of this message is because it feels like a pat on the back for my small attempt to keep good books on shelves where people can get them instead of just destined to be pulped schlock that makes up most of the contemporary best-seller lists.

I'm not doing any justice to my thoughts here with my shitty words. Maybe I will try to edit this later with something enlightening, but most likely not. Instead I'll leave you with a link to a song by one of the greatest Canadian punk bands ever. It kept running through my head as I read this (or actually the last 30 seconds if you really want to know what was running through my head, but don't want to listen to the whole song):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LIF2ef... -

رمان تعویذ را می توان در ستایش شاعران و نویسندگان آمریکای جنوبی و تجلیل از شور و روحیه جوانان دانست ، آنانی که در گمنامی با رژیم های دیکتاتوری از مکزیک تا شیلی چه در خیابانها و چه در محافل ادبی شبه روشنفکرانه جنگیده و در پایان هم نامی از آنها باقی نمانده است .

آنچه در دنیای عجیب یولانیو می بینیم ترکیبی از شک و هذیان و تاریخ است ، شکی که نسبت به همه ابعاد زندگی وجود دارد ، زمان ، مکان و تاریخ و حتی هستی و نیستی . اما یک حقیقت مطلق هم در داستان وجود دارد ، میدان تلاتلالکو و کشتار دانشجویان و جوانان مکزیکی در آن .( اوریانا فالاچی در بخش دوم کتاب

زندگی ، جنگ و دیگر هیچ به این کشتار وحشتناک پرداخته ، او خود در دانشگاه همراه دانشجویان و جوانان حضور داشته و البته در زمان سرکوب زخمی شدید و مهلک برداشته بوده) اما نویسنده با وجود آنکه کشتار تلاتلا لکو را مرکز داستان خود قرار داده اما اصلا به آن نپرداخته است .

راوی داستان آئوکسیلیو لاکوئوتوربه هنگام کشتار در دانشگاه خود را در در گوشه ای پنهان کرده وحال روایت گر داستان شده است ، افرادی که آئوکسیلیو به آنها پرداخته عموما شاعران و نویسندگان گمنامی هستند که سرگشته و آرمان گرا به نظر می رسند ، یکی از آنان آرتورو بلانو است که حضور او در داستان بیشتر حس می شود.

بولانیو سبک بسیار شاعرانه ای برای نوشتن تعویذ انتخاب کرده ، کتاب او سرشار از لطافت و زیبایی ایست و به لطف ترجمه خانم ربابه محب حس و کلام شاعرانه یولانیو به خواننده کاملا منتقل شده است اما تعویذ کتاب سخت خوان و متفاوتی ایست که داستان تقریبا مشخصی هم ندارد . -

When I read the blurb of this novel I laughed. "This is so Bolaño," I thought.

A woman recounts her colourful life in Mexico but... she's telling us all this whilst hiding from members of a right-wing army who have just invaded the university in which she works. Is that Bolaño enough for you?

This might be one of my favourite Bolaño novels. The prose is near lucid but doesn't fall into any of the traps that

Monsieur Pain did and is just short enough to keep your attention through any of the more experimental pieces. This is sort of like if

A Moveable Feast fucked

The Company She Keeps whilst both were on benzos and the aborted baby managed to dictate a book. It's that good. -

Tılsım benim açımdan, yakınlarda okuduğum

Vahşi Hafiyeler ‘den sonra gayet keyifli oldu. Haliyle kitabın bir miktar Arturo Belano içeriyor oluşu da ayrı bir güzellikti. Arturito dışında, Ernesto San Epifano da birkaç bölüm hikayeye eşlik ediyor.

Auxilio Lacouture’ye gelecek olursak, Vahşi Hafiyeler ‘de bahsinin geçtiği bölümlerde üniversite olaylarında yaşadıklarıyla (UNAM ‘dı yanılmıyorsam) beni hem çok güldürmüştü hem de biraz üzmüştü hikayesiyle. İşte Tılsım ‘da o hikayenin öncesi ve sonrasına tanık oluyoruz

Bolano ‘ya başlamak açısından doğru kitap olduğunu düşünmüyorum, öncelikle Uzak Yıldız, Vahşi Hafiyeler ile başlamak (buradan okuduklarıma bakılırsa okuma keyfini arttırmak açısından 2666 ‘yı da okumuş olmak gerekiyor sanırsam) daha doğru olacaktır diye düşünüyorum.

Hem bu kitapta hem de Vahşi Hafiyeler’de bahsettiği 1968 öğrenci olayları ile ilgili kısa bir araştırma yaptım. Aşağıda linkini vermiş olduğum video (ingilizce altyazılı) o dönemi şahitleriyle birinci elden anlatan (o gün Tlatelolco ‘da aktif göreve sahip öğrenci liderleri vs) bir kısa belgesel. Bolano’nun bu olaya neden önem verdiğini şimdi videoyu izleyince anlayabiliyorum. Hakikaten korkunç olaylar yaşanmış öyle ki bugün bile izlerinin hatırlanması gayet mümkün ve anlaşılabilir.

Masacre en Tlatelolco, 2 De octubre 1968 -

Amulet [1999/2006] – ★★★★★

“…those who can see into the past never pay. But I could also see into the future and vision of that kind comes at a high price: life, sometimes, or sanity” [Roberto Bolaño, 1999/2006: 64].

Last year I had a goal to read a certain number of books by Asian authors (see my YARC), and so, this year, I set myself a similar goal, but, this time, I will travel to another part of the world and try to read as many books as possible by Latin American authors. I will begin my Latin America Reading Challenge with a short book by Chilean author Roberto Bolaño (1952 – 2003) titled Amulet. In this vivid “stream of consciousness” account, our narrator is Auxilio Lacouture, a woman from Uruguay and the “mother of Mexican poetry”. She works part-time at one university in Mexico City and at one point realises that her university (National Autonomous University of Mexico) is being surrounded by an army (event that happened two months before the infamous Tlatelolco massacre of 1968). Auxilio finds herself alone and hiding in the lavatory of the university as the army rounds up the staff and students. At that point she starts to recall her own past, talking to us about her dedication to nurturing the artistic talent of others. As time passes and her hunger and exhaustion increase, her account becomes increasingly hectic and imaginative. Amulet is an unusual novella with one unusual narrator at its heart, which is also strangely compelling as it tries to tell us the truth of the situation in the country and the state of Latin America’s literary talent and tradition through an unconventional and slightly dreamlike voice.

One of the great things about Amulet is the voice of Auxilio Lacouture – it is fascinating to follow her train of thoughts because she seems interesting in all her eccentricities and instances of quiet rebellion. Auxilio is a poetess who is passionate about poetry, and her belief in young up-and-coming poets and writers is unwavering. Even though she is clear about the great talent and admiration of her idols, she is unsure about herself, her purpose and her roots, trying to re-imagine herself. “One day I arrived in Mexico without really knowing why or how or when” [1999/2006: 2], says the narrator. Auxilio did not achieve much of what society calls “success”, i.e. a stable job and starting her own family, and, instead, seems to wholeheartedly dedicate herself to poetry. In this way, she is an outsider to traditional Mexico and prefers to lead a bohemian lifestyle surrounded by her friends who are also poets or writers. So, when in Mexico, she starts to clean the house of two Spanish poets – Pedro Garfias and León Felipe, while maintaining her connection to one university at whatever cost to be close to literature and intellectuals.

When Auxilio hides in the lavatories of her university, fearing that soldiers will come and discover her there, there comes that moment in her life when she feels the most alive and aware of life’s fleetness. Her inner reflections on her friends, literature and on the life on streets take the turn of compulsion and necessity. She needs to gather her thoughts and tell us all about it, and she starts to tell the truth through her poetically-charged prose and original worldview. She is from Uruguay and does not fit into the traditional concept of a Mexican woman, and yet she is a woman who finds herself in Mexico, “nurturing” the country’s literary talent. She is both a foreigner and at the very core of Mexican’s formation of its future talented generation – “the mother of Mexican poetry”. At this point, contradictions emerge – she is in time and beyond it. She is in a place where history is made (the siege of the Mexican university) and yet she is beyond this event (does not directly participate in it since she did not surrender to the forces (hiding in the lavatory)). She is an observer, commentator and participator all in one, and her account is both enigmatic and clear at the same time as she then tells of a broken heart of her friend philosopher Elena, of literary aspirations of her friend poet Arturo Belano caught in the war that should not have existed and of her part in the operation to rescue a boy from sexual slavery in the Mexican underworld.

Through Auxilio’s poetically-charged account, we discern the true nature (and sometimes horror) of events happening in Mexico City. Her friend Elena becomes the symbol of Mexico’s “broken heart”/hopelessness and the life of her friend Arturo Belano symbolises Mexico’s lost opportunities in the world and its dismissiveness by everyone on the world stage. It is as though the narrator wants to tell us the truth through certain objects, characters and events, and the result is the account which is erratic, yes, but always compelling as local power struggles in the story tell of power struggles on the whole continent and the conditions of one poet in Mexico City tells about the state of poetry and literature in the whole of Latin America. Catalan painter Remedios Varo and Salvadoran poetess Lilian Serpas are also characters in the narrative which becomes increasingly whimsical and fantastical as Auxilio’s mind starts to play tricks on her under the strain of hunger, hopelessness and exhaustion she feels hiding in the lavatory. Mentioning writers Roberto Arlt, Anton Chekhov and Carson McCullers, as well as the famous plane crash in the Andes, Auxilio makes predictions, and muses on all the lives she did not live and on all the people she admires but will never become. There are a couple of thrilling moments of suspense in the story as we, the readers, start to question whether, far from regarding Auxilio as some madwoman, we should not be thinking about her as a person who sees into everything more deeply and is more keenly aware of the true nature of the situation than anyone else around.

Amulet will not be for everyone. It is a rather eccentric short book which is torn between clarity and incomprehensiveness, wisdom and irrationality, direct insights and almost irrelevant observations. However, at its heart, there is still one distinctive and compelling voice that tries to convey one horrific chapter in the Mexican history, the state of the society, as well as pay tribute to Latin America’s literary ambition and tradition in the only way it thinks it can. -

Nedavno sam gledala neku emisiju u kojoj se autor, eksperimenta radi, pod kontrolisanim uslovima i pred kamerama, podvrgao nekom ritualu Inka (recimo) koji za cilj ima konekciju sa Suštinom Bića Univerzuma (kao takvog!). Naravno, sve se vrtelo oko neke retke travke, ubrane na samom vrhu besputno udaljene litice, pa se to onda sušilo u, recimo, gornjem levom uglu potkrovlja sojenice u kojoj žive tri žute mačke i četri žene sa po šest nožnih prstiju (sve četri device, razume se), pa se to stucalo u specijalnom avanu i to 28 dana od 6. mladog meseca u godini kad je, recimo, Neptun bio u polusekstilu sa Spikom. Onda se dodaju kapljice rose sa još žešće strmine i svakorazni sastojici još, al' najvažnija stvar je da uz tebe bude šaman, koji duva u sviraljku dugačku tačno devedeset šest i po dužnih jednica Inka, sav u perlama i perju. Posle malo obesi o vrat i neki bubnjić – konge neizrecivo egzotičnog naziva, kad shvati da baš teško podnosiš (al' ne nekontrolisan proliv i povraćanje, ridanje u delirijumu, bacakanje unaokolo i oduševljenje sopstvenim prstima – to je normalna reakcija – nego da ti veza sve nešto puca i traljavo kapiraš šta ti Kosmos poručuje). Kad ti šaman pomogne, onda je sve ok.

Taj je pokusni autor na kraju sve potanko opisvao emocije kroz koje je prolazio i sve je to delovao veoma uverljivo, ali smo mi, koji to progutali nismo, mogli samo da mu verujemo na reč. Ili ne.

E, tako je i sa ovom Bolanjovom knjigom.

Dakle, šah – mat: evo moderne književnosti koja ne čekića po ustaljenim vrednostima u nameri da dođe do crvotočine, već svirucka na nekoj dva'es sedmoj frekvenci, gledajući na sve prethodno normalnim pogledom, ni zadivljeno, ni omalovažavajuće.

Bolanjo je, kažu, jedan od osnivača avangardnog pesničkog pravca „infraracionalizam“. Nomine! Jeste, podižem malo obrvu na to, ali zadovoljavajući odgovor na pitanje zašto – nemam. U istoj sam poziciji i za ocenjivanje ovog romana: na sve što bih zamerila, on odgovara smislenim protivargumentom, iako nedovoljno snažnim da me natera da promenim mišljenje. Tako ostajemo u nekakvom lebdenju, ali ne i ambivalenciji. Sve je u nekim snoviđenjima, magično veličanstvenim slikama, nabijeno erotikom (lascivnost mu ni ne pada na pamet), puno života i aveti, ljubavi, bede, iluzija o slobodi...ma čega god hoćete ovde ima. Centralna figura je wanna be muza, a zapravo sredovečna krezuba tetkica u plisiranoj suknji sa princ Valijant frizurom, gruppie ženskica mladih meksičkih pesnika, koja sebe naziva njihovom majkom. Ona u vreme vojnog udara '68. skoro dve sedmice ostaje zatvorena u klozetu katedre za književnost i filozofiju čuvenog univerziteta u Meksiko Sitiju. I...let's roll, Bolanjo!

Al' fabule nema, sve je njen šizofreni monolog, vremenski neuhvatljiv, o prostorima da i ne govorimo.

Čvrsto bih mogla da stanem samo iza sledećih tvrdnji: ili Bolanja boli uvo za (proznog) čitaoca, ili se obraća užem krugu onih koji su čitali (poeziju), naročito modernu, naročito latinsko američku i to u Meksiku, tačnije po nekim tamošnjim kružocima – kafanama do kasno u noć. Naravno, takve prilike podrazumevaju nekakve interne alegorije tj. malo izmeštanje uobičajenog značenja. Neku novu slobodu izražavanja, da kažemo finije. Mi, neosvešćeni, moramo da se zadovoljimo samo krupnijim kadrovima u kojima se nalazi besmrtnost umetnosti i borba da tako besmrtna i ostane.

Prevodilac Dušan Vejnović, i sam pesnik (kako čovek da ne voli Flavia Rigonata!?), sem što je zaista lepo preveo roman, svesrdno se potrudio da u napomenama da što više objašnjenja, ali je moje poznavanje kulturno - istorijskih trendova u Meksiku i Čileu sedamdesetih godina prošlog veka na for dummies nivou. Tako sam sve čitala kroz neku koprenu, gušću nego prošli put sa Bolanjom (Čile noću).

Sledeći pouzdan zaključak je da je Bolanjo pesnik, pre svega pesnik, koji ne želi da bude ništa drugo sem pesnika, u najširem značenju te reči: od boema, preko politički angažovanog klošara na ivici egzistencije, do zanesenog čudaka.

Ne mogu da prećutim da je, ipak, malo predoziran, ili, preciznije, pretrpan kad je u prozi.

Neki kažu da je ovo uvertira za roman „Divlji detktivi“, a drugi da je njegov poetičniji nastavak. Kako bilo, od Bolanja neću odustati. Trebalo bi mu se posvetiti malo štreberskije, al' meni meksička poetska kretanja nisu baš visoko na spisku prioriteta.

Neka bude 4, najpre za te lude slike i izuzetnu poetičnost, ali ne savetujem da se sa Bolanjom počne odavde, ako bih uopšte preporučivala Bolanja.

-

Η Αουξιλιο Λακουτυρ, η "μητέρα της ποίησης" του Μεξικου, βρίσκεται κλεισμένη για 12 μέρες στις γυναικείες τουαλέτες του Αυτόνομου Πανεπιστημίου της πόλης, κατα τη διάρκεια δηλαδή της εισβολής της αστυνομίας τον Σεπτέμβρη του 1968. Απο κει διηγείται ιστορίες που συνέβησαν, συμβαίνουν ή θα συμβούν στο μέλλον ακολουθώντας τη Σελήνη που φωτίζει τα λευκά πλακάκια της τουαλέτας. Οι πολλές ιστορίες έχουν μοναδικό κοινό στοιχείο την αφηγήτρια, η οποία μεθυσμένη, συνήθως, πηγαίνει απο παρέα σε παρέα, απο σπιτι σε σπιτι κ κινείται σαν φάντασμα ανάμεσα στα σημαντικότερα γεγονότα της εποχής. Ενα βιβλιο-έκσταση, ο κατάλληλος τρόπος να μπεις στον κόσμο του φοβερού αυτού συγγραφέα. Εξαιρετικό.

-

Roberto Bolano’dan yine kendine has, harika ve etkileyici bir roman. Arka planında Meksika'da 1968 Eylül'ünde öğrenci protestolarının kanlı bir şekilde bastırılması olan, ama ana karakterleri yine edebiyatçılar (şairler) ve edebiyatseverler olan bir hikaye. Bolano'nun alteregosu olarak kabul edilen Arturo Belano da yine sahnede, bu sefer 17-18'lik bir delikanlı, Arturito olarak. Başta, bahsettiğim öğrenci olaylarında üniversite tuvaletinde 13 gün saklanan baş karakter Auxilio'nun hikayesinin biraz sıkıcı olabileceğinden endişe etmiştim. Ama Bolano ve sıkıcılık herhalde pek yan yana gelmez. Nitekim Auxillio'nun kimi zaman düşsel nitelik kazanan anıları biçiminde anlatılan hikaye okuyanı kendisine bağlıyor. Çarpıcı da bir finali var. Çeviri de (Zeynep Heyzen Ateş) çok iyi. Bir de Bolano'nun bende şiir okuma isteğini tetikleyici etki yarattığını söyleyip çekileyim.

-

Μια αγωνιώδης, πηχτή ιστορία ενός σκοτεινού καιρού που φωτίζεται μονάχα απ' την αντανάκλαση της σελήνης. Αλλά και μια σπουδαία μεταφραστική στιγμή του Κρίτωνα Ηλιόπουλου. Ο συγγραφέας των συγγραφέων, ο Roberto Bolaño, εξασκείται με την γνώριμη, μεγάλη του τέχνη στις αποχρώσεις της τρέλας και της ελπίδας, της παραίσθησης και της διαύγειας.

-

This is a horror story. A story of murder, detection and horror. A story of a terrible crime.

She was in the bathroom of the university when the army and the riot police occupied the campus and arrested the faculty members and the students, killing them indiscriminately.

Life is full of enigmas, minimal events that, at the slightest touch or glance, set off chains of consequences…

She is left alone, undetected but after days of solitude and hunger, she begins having hallucinations, recalling the past and foreseeing the future.

Let’s just say I heard a noise.

A noise in my soul. -

O-bir yazar

O-bir okur

O-bir hipnotizmacı* gözlerimizi yuvalarından çıkarıp kendimize ve dünyaya ve dünyada olan bitene ve acılara ve dostluklara ve bulutlara karışmış dönüp duran şiirlere baktıran

O-yanardağlara düşüp düşüp yeniden doğmuş ve yanmak nedir çok iyi bilen ve dili tutulmuş ve hikayesini işte bu dilsizlik sayesinde anlatabiliyor

O-unutturan ve hatırlatan ve teselli eden ve her şey ne kadar da zor ama İYİ Kİ YAŞIYORUM ve bunlara şahit oluyorum ve

O; KELİMELER NASIL OLUR DA BÖYLE BİR ARAYA GELEBİLİR???

O BolanYO;

bir tuvalet çukuruna günlerce ve haftalar ve aylar ve yıllar ve yüzyıllarca bakabilir ve size öyle şeyler anlatır ki daha duymadan dudaklarınız uçuklayabilir ve biri bana ciddi ciddi cevap versin lütfen? İNSAN KAÇ YILDIR DÜNYADA GEZİNİYOR?

ve bir şeyler eyliyor ve birileri birbirine şiirler okuyup, bok gibi kimsenin beğenmeyeceği resimler gösterip ve kokuşmuş bedenler ve fakirlik ve bu alkol kokusunun kaynağına doğru yürümek ve dünyanın var olmaya başlamasından beri sürekli düşüşüne devam eden bir VAZO varken, ve birileri birilerini gerçekten- öyle içten- öyle güzel sevebilirken- iyi de bu ÇOK GÜZEL, buna şahit olmak, bu düşüşe ve karşı düşüşe, bu uçuşa, süzülüşe ve PAT!!!

duyduğum sadece patlayan bir balonun sesi miydi yoksa birilerinin birilerini kurşuna dizişine mi şahit oluyorum? -anlam ve anlamsızlık, bulanıklık ve berraklık evrende yaşam potansiyeli barındıran her hücrecik kavrulup yok olana dek birbirine yaklaşıp uzaklaşarak salınımına devam ediyor. A-aa! BU BİR DANS!

ve birbirlerine değdikleri anda ne olacağını size söyleyeyim:

PUF!

ama bu kitap, bu tılsım, iki (güya)zıttın birbirlerine asla değmeyeceklerini ve danslarının ebedi ve ezeli olduğunu fısıldıyor.

Anlamıyorum. Bir şey nasıl olur da bu kadar güzel olur?

Sim içinde kaldım, parlıyorum ve parlamak çok hoşuma gidiyor. Işığımdan dilim ve gözlerim ve dişlerim kamaşırken;

İşte; küçük ve kocaman dünyamız böyle bir yer.

İşte; görüp görebileceğin bu; ve bunu --tam olarak bu şekilde--tattığın için çok şanslısın.

Şimdi gözlerini olabildiğince aç ve içine tüm insanlık tarihinin usul usul dolmasını bekle.

Bazen zevkten çıldırasım geliyor.

Sevgiler. -

This is going to be a horror story. A story of murder, detection and horror. But it won't appear to be, for the simple reason that I am the teller. Told by me, it won't seem like that. Although, in fact, it's the story of a terrible crime.

I do not know enough about Mexican history to really grasp the "terrible crime" that is the focus of this story, or its implications on the Mexican memory (though I have read a little since finishing the book). Amulet is an attempt to come to terms with this crime - the Tlatelolco massacre - which resulted in hundreds of students being killed at the hands of military and police. Thematically, the novel feels very close to Slaughterhouse 5, and even employs time as a device in a similar way. Though her power to do so is perhaps more poetic than Billy Pilgrim's, like him, Auxilio Lacouture moves freely between past, present and distant future, as a means of rationalising and contextualising the traumatic event within the context of the greater arc of history.

Lacouture is the embodiment of the artistic sensibility: she is powerful, captivating, and yet she is damaged. She is the ideal witness to this literary search for meaning. At a high point near the end of the novel, she reveals a prophecy, which at once epitomises both the transience of art and its enduring nature. There is a bittersweet kind of hope expressed in these passages, which are the culmination of the novel: the acceptance of the inevitability of decay, alongside a solemn prayer for renewal, and redemption.

A love of poetry and literature permeates this a beautifully-crafted little novel. This was my first Bolaño. I feel that I will be in safe hands when I undertake to read 2666 next year. -

3.5/5. Here we go again. Mexico and Poets. And in particular one Arturo Belano. He sure does get about. As a Bolaño fan I find it so easy to get caught up in his universe and not want to leave. I think I would use the word hypnotic. I Pined for other 1000 pages of 2666. Couldn't stop thinking about The Savage Detectives for weeks. And there was something about Distant Star that made me want to re-read it straight away. I can't really find anything negative to say about Amulet, and Bolaño's distinctive mood and tone, and dreamlike melancholy and mysteriousness from other novels was ever present. The reason for the three stars - well, lets say three-and-a-half - is that I can't rate this without taking those three books into account. This for me simply wasn't anywhere near that level. Auxilio Lacouture - minor character from The Savage Detectives - narrates this short novel, which I got through in one afternoon, mostly centres on the troubled political climate of Mexico in 1968, and in particular the massacre that took place in the Tlatelolco district of the city involving university students and staff members. Again we get fictional people along with real ones, including a brief apperance from Ché Guevara, and the mention of plenty of poets. There wasn't really a plot to speak of but that's not my main priority when reading a novel. Auxilio's voice throughout, as she moves about the bars and cafes with a mixture of optimism, insecurity and resistance was really well done. The ending here was a powerful and moving one; a ghostly hallucinatory one, almost like Bolaño's tribute to the ever so many that fell never to get up again. -

1968 yılında,Mexico City’de, Eylül ayında, tanklar ve askerler üniversiteyi işgal ettiğinde, UNAM Kampüsü'nde Felsefe ve Edebiyat Fakültesi'nin dördüncü katındaki kadınlar tuvaletinde saklanan, tek lokma yemek olmaksızın 8 gün direnen,

katliamdan geriye kalan son kişi olan Auxilio Lacouture’nin (aslen Uruguaylı Pedagog Alcira Soust Scaffo) öyküsünü anlatıyor R. Bolano.

Tuvalette isteyerek kapalı kaldığı bu süre içinde yaşadıklarını Bolano’ya anlatan Scaffo’nun öyküsünü daha önce “Vahşi Hafiyeler”de bir bölüm olarak çok etkileyici bir şekilde yazmıştı yazar. Şimdi ise kendisine anlatılanları Locauture’nin öyküsü olarak okuyucuya anlatıyor.

Auxilio’nun yaşadıklarını, geçmiş, o an ve gelecekle harmanlayayıp, Güney Amerika’nın tarihini, antik Yunan mitolojisini, çoğunluğu latin kökenli şair ve yazarları öyküsünün içine yerleştirerek olay kahramanının deliliğini, ölümcül öfkesini, utancını ve pişmanlığını şirsel bir dille ve düşlerle anlatıyor Bolano.

Özünde hâlâ dördüncü kattaki tuvalette kilitli olan Locauture’nin Vahşi Hafiyeler’in “ArturoBelano”su ile ilişkisini ancak o romanı okursanız yerine oturtabilirsiniz, bu nedenle önce “Vahşi Hafiyeler” okunmalı. -

تعویذ، مرثیهایست برای رویایی که جوانان مکزیک در سال ۱۹۶۸ داشتند. احتمالا هرکسی که از کتاب ِ "بیقصه" اما "پر از حس" خوشش بیاد، کتاب رو از ابتدا تا انتها زمین نخواهد گذاشت.

و ترجمهی این کتاب، شگفتانگیزه! عالیه! زیباست! رباب محب در این کتاب، فوق العاده عمل کرده و تونسته لحن و حس نویسنده رو، به فارسی دربیاره. دستش درد نکنه ❤ امیدوارم ترجمههای بیشتری از ایشون در ایران چاپ بشه. -

"Aşk "iyi"yi getirmez. Aşk her zaman "daha iyi"yi getirir. Ama kadınsan daha iyi bazen kötü demektir."

"Hepsi tesadüf olamazdı; kimse kaderin tuzaklarından, kumpaslarından ve gizli hesaplarından muaf değildir."

🖤 -

Vahşi Hafiyeler i okurken en etkilendiğim kısımlardan biri üniversitenin işgali sırasında Fen -Edebiyat fakültesinin tuvaletinde mahsur kalan şairlerin anasının hikayesiydi.

Bu kitapla o etkilenme tuvalet fayansları boyunca genişledi ve keyif fayansların üzerine düşen ay ışığı boyunca sürdü.

Kitap başında bir korku hikayesi olduğunu söyleyerek bir de ismi ile beni çok şaşırmıştı neden diye soruyordum hep.

Şimdi o Tılsım ın ne olduğunu biliyorum.

İyi ki varsın Bolano! -

Vidim ja, Bolanjo mi je odnekud poznat. Kao da sam ga video negde u prevozu, usput.

I onda mi je sinulo. Bolanjo neodoljivo liči na kombinaciju Ace Popovića i Kita Heringa. Ma isti!

Tako sam u Bolanju kao u kinder-jajetu pronašao dve igračkice. Pridružuje im se još jedna figura – pravo sa korica, čini se, neka devojčica sa Anda, Indijanka, prekrivena cvećem – kad ono ni manje ni više nego Jajoi Kusama. Sve sam omašio – od kontinenta do konteksta. Ali kao i kod Bolanjovih „dvojnika” (uz još jednog u samom delu – Artura Belana), „Amajlija” je dom i devojčici iz plemena i japanskoj umetnici beskrajnih soba i tačkastih bundeva.

Ovaj roman jeste skaz na federima – rolerkoster utisaka i aluzija ogromnih amplituda – od razočaranosti i frustracije do potpune oduševljenosti. Auksilija Lakutur (to su savršeno primetile Tijana i Nora!), predstavlja jednu od najupečatljivijih pripovedačkih figura sa kojom sam se sreo, kojoj, kao doduše, gotovo sve u ovom delu, ne znaš kako da priđeš. Ali ona uporno tebi prilazi sa rafalima izuvijanih priča s koca i konopca o istorijskim turbulencijama, anegdotama o književnoj sceni, književnim fundusima i književnim aferama, Popokatepetlu, muškim prostitutkama, taksisti-iguani, Orestiji, proročanstvima, zubima, seksu sa Če Gevarom, anemiji kao nostalgiji, Meksiko Sitiju. Samo da ostaneš u čudu.

A jedno od čuda je što sam pomislio da je ovo beskrajno lokalno delo – gotovo ništa vezano za živote latinoameričkih pisaca, nije mi bilo poznato. Takve su okolnosti, čini se, da u „Amajliji֨ mogu uživati samo geo-poetički insajderi. Međutim, na neki čudan način, zaobilazan način ovo je došlo do mene. I to ne samo u odnosu na tonu čitalačkih preporuka koje sam vredno zapisivao, nego nekom svežinom koju nisam mogao naslutiti. A svež savremeni glas mi je vrhunska valuta.

Da stvar bude još neobičnija, ovo nije eksperimentalni roman. Makar ga ne doživljavam(o) tako. Ne pripada ni onoj sve jeftinijoj etiketi magijskog realizma. Nema priče, a sve vrvi od priče. Nema poezije, a vibrira poezija. Dosadan je i prezanimljiv. Krcat intertekstom (infratekstom!), a ne uzdiže nos. Svašta je „Amajlija” i posebno, čini se, pista za uzletanje na ona velika dela (i po dimenzijama i po hvalama). Neće mi promaći ni „Divlji detektivi” ni „2666”.

Kad smo već kod toga, broj 2666 se, koliko sam obavešten ne spominje u istoimenom romanu, nego upravo ovde, u „Amajliji” – i to u kontekstu groblja iz budućnosti. (71) Misterija koja može da pokaže koliko su sva Bolanjova dela međuzavisna i isprepletana (te se Amajlija može čitati kao siroče-poglavlje neke nad-knjige) i koja ni nema razrešenje jer ga ni ne želi. Ali malo sam se igrao ciframa i dobio sledeće – roman je izašao 1999. a napisan je godinu ranije. Dobro. E sad, ako bismo 999 prevrnuli, dobili bismo tri šestice – 666 (za koje svi znamo šta znače), a ukoliko ne želimo da odemo u prošlost završićemo u prvoj sledećoj mogućnosti za pojavljivanje te tri šestice jedne pored druge – u 2666. godini. A možda se Bolanjo i katapultirao u budućnost i tamo se smeška, piše unatraške.

I da, poznata je (ne samo) moja opsesija neobičnim motivima. Ovog puta pomenuću, poprilično odbojan motiv muške menstruacije. U srpskoj književnosti imamo ga u dva izuzetno poznata romana – „Kad su cvetale tikve” (oličena u periodičnoj žeđi za Jugoslavijom i pranju benzinom na granici) i „Peščanik” (srce koje menstruira). Komedijant slučaj je udesio da ovaj motiv postoji i kod Bolanja. (76) -

"And although the song that I heard was about war, about the heroic deeds of a whole generation of Latin Americans led to sacrifice, I knew that above and beyond all, it was about courage and mirrors, desire and pleasure. And that song is our amulet."

The writing for this book is absolutely beautiful, that is honestly the top thing that sticks with me. The whole book is so beautifully written I wish I spoke Spanish to read it in its original form.

I'm so glad I read this twice because it was much easier to understand the second time once I had more of a picture of the overall story.

Amulet follows a Uruguayan woman named Auxilio who refers to herself as the mother of mexican poetry and living a bohemian lifestyle in Mexico among young poets she has befriended.

The story centres around Auxilio, who she becomes trapped inside a toilet in the Mexico City university after the riot police come to remove the students and professors. This is based on a true incident. Alone in the toilet for 13 days, she begins reading a book of Mexican poetry she had with her and thinking about the state of modern literature and latinx literature, as well as how this connects to the history and present state of Mexico and the rest of Latin America. The author is Chilean but spent a lot of time living throughout Latin America and I really thought it was interesting how he also wrote himself into the story.

This is such an interesting and unique read, and honestly I am really loving reading more literary fiction thanks to University. I'm going to have to try and keep it up even when it's not required reading.

“Still I kept walking. I walked and walked. And from time to time I stopped and said to myself: Wake up, Auxilio. Nobody can endure this. And yet I knew I could endure it. So I baptized my right leg Willpower and my left leg Necessity. And I endured.”