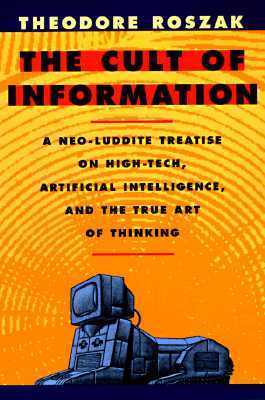

| Title | : | The Cult of Information: A Neo-Luddite Treatise on High-Tech, Artificial Intelligence, and the True Art of Thinking |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0520085841 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780520085848 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 267 |

| Publication | : | First published October 31, 1985 |

In this revised and updated edition of The Cult of Information , Roszak reviews the disruptive role the computer has come to play in international finance and the way in which "edutainment" software and computer games degrade the literacy of children. At the same time, he finds hopeful new ways in which the library and free citizens' access to the Internet and the national data-highway can turn computer technology into a democratic and liberating force. Roszak's examination of the place of computer technology in our culture is essential reading for all those who use computers, who are intimidated by computers, or who are concerned with the appropriate role of computers in the education of our children.

The Cult of Information: A Neo-Luddite Treatise on High-Tech, Artificial Intelligence, and the True Art of Thinking Reviews

-

First published in 1986, and updated in 1993, Roszak's book is now dated in a number of respects – a danger likely to befall any account of contemporary technology. And so, even with the updated edition, this makes some of it quaint and occasionally short-sighted. At the time of writing, there were no social media platforms, no smartphones, and the Internet had merely begun to hint at the way that it would connect people and change the way we live.

It's a good thing then that the core value of the book – and what gives it enduring appeal and relevance – lies in its philosophical underpinning. The "cult of information" that Roszak identifies is one that still informs our present day attitudes to technology, and in fact seeing how deep the historical roots of it go can give us a new appreciation of the scale of the problem.

Roszak's central thesis is that technological enthusiasts have – wittingly or otherwise – confused information with knowledge. But information – bare listing of facts, collection of data – is not knowledge any more than the ingredients that make up a meal constitute sustenance. They must be combined, processed, internalised, broken down, digested – well, I'm sure you understand the process of eating! Until we perform a similar process on information, it can never become knowledge, can never become a useful and nourishing part of us. A key distinction that Roszak makes is therefore between information (data) and ideas. Ideas are what make sense of information, tell us which bits are relevant, how they relate to one another, and so on. So the idea that, by merely introducing it into our lives, a computer or a piece of software can furnish us with knowledge is ridiculous – and yet, as Roszak argues, this is exactly what purveyors of information technology would have us believe.

Much of the book tracks the spread of this cult through society - education, business, media, politics, the military, public services. The majority of this material is either still depressingly relevant, or with a twist may be updated for our current situation. For instance, in 1993 the British electrical grid was stil reliant upon an antiquated computer that utilised a programming language that only a single person understood (and whose illness or unexpected demise would... it doesn't bear thinking about). In 1993! And yet there still exist now modern systems that rely on obsolete technology and software (witness the 2017 Wannacry computer virus attack on the NHS that revealed how many of its computers were still running Windows XP...).

Another focus is upon the way in which the spread of computers has seen both the overestimation of the trajectory of computer evolution (which will soon outpace us), and a corresponding undervaling of human thinking (humans are merely machines – and not very good ones). But as Roszak points out, both these claims are in specific ways false. Despite the claims of techno-cultists and AI enthusiasts (which have been predicting superintelligent computers as just around the corner for almost as long as computers have existed), no machine as yet even approaches the level of general intelligence that even an infant possesses. So while there are specialist systems that can beat chess grandmasters, there yet exists no computer with enough "common sense" to get out of the rain (or perform any number of other equivalently simple tasks that we wouldn't think twice about). People are not data processors – we are more than that – and we shouldn't let the prodigous but narrow skills of AI make us forget that.

Datedness aside, there are a couple of places where Roszak overstates his case, or underestimates the potential for computing evolution, but on the whole his points remain insightful and sound. One minor point I would take issue with him on is his estimation of English philosopher Francis Bacon, whom Roszak sees as holding the view that problems can be solved simply by collecting enough data. I think this is not only unfair on Bacon, but false. Bacon did indeed advocate the widspread collection and comparision of experimental data and empirical observation, but it was with a view to improving our powers of induction – that facility of the mind (which Roszak praises) to identify patterns and draw general conclusions. Induction is what makes sense of data, but Bacon concluded that it needed training, for we were too prone to draw conclusions prematurely (a similar point to that made by Daniel Kahneman's "Thinking, Fast and Slow" – which is also on my reading list). This aside, I mostly agree with Roszak's views, and I think his diagnosis of utilitarianism as the quantity-obsessed belief system underpinning the cult of information is spot on.

The book is subtitled "A Neo-Luddite Treatise", and makes the link between the orignal 18th century industrial vandals and the modern counter trend of technological scepticism. Ludditism has received a bad press – mostly from the descendants of the means-of-production-owning forces that won out in that industrial skirmish – as being anti-technology or anti-progress. But in fact Ludditism was concerned with the struggle to preserve human dignity and values in the face of dehumanising technological forces masquerading as "progress". In this sense, it was anti-exploitation and anti-inequality – principles that a Tweeting, emailing, Instagramming Neo-Luddite can get behind without hypocrisy. (Well, OK, not Facebook. Nor Google, maybe. Nor Apple...)

Gareth Southwell is a

philosopher, writer and illustrator. -

Thedore Roszak shows how the benefits of computers' powerful ability to collect and process data are overexaggerated. He does not attack computers per se, but he does highlight the abuses and limitations of computer technology. For example, computers' data processing are frequently touted as a model of human thinking, hence the development of the academic field "cognitive science." Roszak shows that is simply not the case, humans rely too often on intuition and fuzzy logic as opposed to the mathematical, procedural thinking of computers. In addition, he shows how the craving for data has weakened democracy. He takes the view that politicians' frequent use of the polls has reduced democracy to "opinion-mongering" instead of real political debate.

There are two themes that run through the book, the Luddite theme (after all, this book is called a neo-Luddite treatise) and the humanistic theme. Roszak frequently mentions how the increased use of technology will displace teachers and librarians and take the human face out of various professions. Fair enough. The humanistic theme that runs through the book is fairly obvious. He does not state that computers are inherently bad, but simply asks us at many points to consider the possibility of a culture that idolizes the computer and its data instead of human-to-human interaction. He omniously implies that in some ways, that future is already here.

A brilliant argued and thought-provoking book, highly recommended. -

This work, written by a professor of history at California State University (2nd ed ed 1994), does a good job at discussing the prevelance of information technology in modern society. A major problem with this work however, is its North American centricness. The United States is too isolationist in outlook and this treatise is a typical example of this. Another fault is the simplification of the librarian’s role. Rosak states that librarians are “cultural generalists rather than information specialists”. This may be the case in academe and in the public forum, but in special libraries and information centres, librarians or Information Specialists, work in specific fields and are expert in the types of information handled within them. Despite these major faults, this work is a thoughtful venture into the philiosophical debate about thought, information/data,

artificial intelligence and modern life. -

Sorry to say, I gave up on this book pretty early on, so I don't know if there was anything good in it. Mostly the problem was that by the time I got through reading the introduction to the revised second edition, I had very little patience left for the actual book. I wanted to give it a chance because there's always room for discussion and analysis of what changes are taking place in society due to technology, recognition of other alternatives could potentially be taken rather than accepting certain things as inevitable, and what the trade-offs and likelihoods are of those alternatives and a frank acknowledgement of the collective choice we are making as we adopt a technology in certain ways.

The first introduction, to the original edition, was hopeful, trying to be very clear that the author was not saying that computers are the devil and we should burn them and go back to the good old days of using sticks and leaves for all our communication, but rather trying to discuss the ways in which computers were being used, especially potentially and actually harmful ways, and in light of the way those uses are being advertised and sold. The second introduction, ten years later, as the encroaching of computers and the internet into the fabric of ours lives was only increasing, erased most of that hope. One issue that I can't fault the author for is that I'm reading it 20 years later, which changes my perspective enormously. Many complaints could have been addressed if he'd just waited. There are still plenty of things that are only available to the elites, sure, but a lot of his complaints about computers being too expensive or just user-unfriendly to be good to anyone else just needed time for the costs to come down and for there to be any development of good practices for user friendly interfaces.

But maybe that's not that different from other things that turned me off - like his bemoaning the fact that people are using computers for low brow entertainment and porn. "But I have often wondered how cognitive scientists and idealistic hackers must feel, knowing that the technology some among them regard as the salvation of democracy and the next step in evolution is being squandered on so many unbecoming uses." I mean - what - how do you explain that a) it's people, dude, they're gonna use whatever is around for stuff that you personally don't like, that's just how it works, man, and b) technology (or any tool or anything, really) isn't one single platonic thing that is somehow, I don't know, sullied, if any of it, anywhere, at any time, is used for something other than your One True Purpose. I, personally, happen to be a painfully naive and idealistic idiot, still somehow believing or hoping that we can really do amazing things with some combination of human brains and things that exist as a result of human brains, but knowing that somewhere, someone of the 7 billion people on this planet, is acting in a way not in accord with that plan doesn't really bother me.

Anyway, so by the time I got to the actual book and started reading about how before we had information science as a field, or other related developments, people used the word 'information' differently than we do now, given the past 100 years of history where our world view and language and society have developed and changed as they always do. Those pure and simple folk would find it quite silly the way we use the word 'information' today, not having any of the conceptual framework that evolved over decades of discovery that has by now worked its way into the general public consciousness. I think it's pretty cool how the very way we think of the world changes, and yes probably even important to understand how it comes about since, yes, we shouldn't be too attached to our current way of viewing the world, since it's a product of the present, contingent milieu and not strictly true. And maybe if I would have kept reading he would have come around to this point, and not just continued with 'It's obviously foolish of us to think of information in this way because people didn't used to'. In fact, I'm fairly confident there would be more interesting points made, plenty of things I could get on board with. The problem is, I was already so tired after all the somewhat less reasonable complaints, and didn't have the energy to wade through more of those in order to pluck out the good stuff. I bet this would really be worth reading if I were specifically researching attitudes about technology, and predictions, and the like. But I am not, and just for my own personal consumption, when the internet has granted me access to millions and millions of books and articles and videos and websites and communities, it just doesn't seem worth it to me to take the time to read the rest of this book. -

Si bien el lenguaje usado por Roszak es de choque, la visión muy al contrario de las críticas que he leido, no es tecnofóbica sino promotora del juicio crítico y de dilemas éticos. Un buen libro para salir de los moldes en los que me muevo.

-

Here is a critique of information technology from a humanistic perspective, focusing on the way the "data-processing model of thinking," a quantitative, ultimately binary, model of the mind on which computers are based, threatens to replace ideas as the dominant mode of thought in education, politics, and social life generally. This result of the mystifying effect of computers comes from the aura of certainty and mathematical precision bestowed on them by tech-enthusiasts.

Because it is hopelessly out of date when it comes to "contemporary" developments (1986 edition), the book is hit-or-miss. I would have liked to have seen either a deeper discussion of the philosophical argument or merely have the several chapters that ventured into highly specific cases cut out. Overall a disappointing follow-up to

Where the Wasteland Ends, but the dispersed gems of wisdom it contains make up for its problems. -

Roszak was ahead of his time 25 years ago. The only major criticism is that the book is dated. He was arguing for proper use of technology, ethically and legally, and for a real economy to remain and not a data economy appearing to be rising up to replace it. He is right on all arguments made in the book and sadly, his progrnostications have come true. So for me the ugly truths manifesting itself 25 years later and the technology history lessons, all though well done, made this a difficult book to engage.

-

If this book shows anything, it's that most ideas floating around today have been around for much longer than you'd think. The singularity has been "10 years away" for 40 years now. The surveillance society has been fully implemented and exposed. Military leaders have used experimental data as gospel. Having grown up with computers and the internet, perhaps I have also taken it as sacrosanct.

-

I did enjoy the book which is inspirational at times. I skipped 5 of its 11 chapters (3, 4, 7, 9 and 10) since a book on computer technology written in 1986 with a second edition in 1994 is necessarily somewhat dated. However, a lot of the comparison between the processing capabilities of computers and the thinking processes of humans remains valid.

-

Masterful

-

Of all the cults one could join (or lead), the cult of information is the least sexy of them, and yet it is arguably the most popular one in operation today. Most of the information is still valid.

-

The best part of this book is the fascinating history of the origins of both computers in general and PCs especially -- the latter began in the counterculture which now seems pretty weird. Roszak shares similar views with Neil Postman and Clifford Stoll, two writers I've enjoyed reading.

The main point of the book, though, was to be a carefully written expose of the "cult of information", those who believe that a computer can do anything a human can do, only better; and that data = information = knowledge. I am skeptical! A good read to make you think more about how our technology must be used by us rather than letting it use us. -

Roszak takes aim at the some of the conceits of the Information Age, which principle crimes are confusing information with knowledge, and information processing with thought. He generally hits his mark, too. Though his attempts to circumscribe the limits of electronic computation for all time are just a confused jumble of metaphysics.

-

This book has really but a thought into my head about how I should think when technology is to be used in an educational setting. It is probably better to have a discussion group like I did (I was forced to read it for my graduate class).

-

I love this book because it sets out in very reasonable terms the main reasons we should forbid all use of computers in public schools and force people to learn how to read and think first.

-

Dated in that it was updated nearly 20 years ago and originally written nearly a decade before that, but his thesis nevertheless stands.