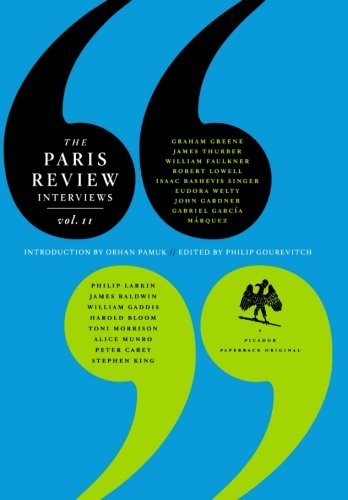

| Title | : | The Paris Review Interviews, II: Wisdom from the World's Literary Masters (The Paris Review Interviews, 2) |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0312363141 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780312363147 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 528 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 2006 |

The Paris Review Interviews, II: Wisdom from the World's Literary Masters (The Paris Review Interviews, 2) Reviews

-

Stop licking melted popsicle juice off your fingers and listen to the full pod

here.

An excellent collection of interviews from some of the 20th century's finest writers, along with some people I haven't heard of (and I'm not going to tell you which is which, so you can't judge me).

I break down the best quotes in the pod, along with the insights that illuminate our present literary epoch. I will just state here: thank god for James Baldwin and Toni Morrison.

Without them, a solid portion of this book would just be 10 white guys, self-inducted into the inner ring of "most impactful writer illuminati," taking subliminal or even overt shots at each other. They like to say things like, "well, what he doesn't understand about the nature of fiction is (((fart noise))))."

Later, a rebuttal will come in the form of, "and the thing that he fails miserably at, beyond metaphorical layering, is clearly the (((louder fart noise)))."

All of which culminates in the last self-congratulating white dude saying, "the authenticity of my writing, which neither of them can comprehend, actually originates out of (((sharts pants)))."

This has been my contribution to literature, thank you. -

INTERVIEWER - How does a writer become a serious novelist?

William Faulkner - He must never be satisfied with what he does. It never is as good as it can be done. Don't bother just to be better than your contemporaries or predecessors. Try to be better than yourself.

Orhan Pamuk - I drew upon these writers varied habits, eccentricities, and little quirks (such as insisting that there always be coffee on the table). For thirty-three years now, I have been writing longhand on graph paper. Sometimes I think this is because graph paper suits my way of writing....Sometimes I think it is because I learned that two of my favorite writers, Thomas Mann and Jean-Paul Sartre, wrote on graph paper.

INTERVIEWER - Some commentators on the current scene, notably Marshall McLuhan, feel that literature as we have known it for hundreds of years is on it's way out. The reading of stories and novels, they feel, is soon to be a thing of the past, because of electronic entertainments, radio, television, film records, tapes, and other mechanical means of communications yet to be invented. Do you believe this to be true?

Isaac Bashevis Singer - If we have people with the power to tell a story, there will always be readers. I don't think people will change to the degree that they will stop being interested in a work of imagination. Today nonfiction plays a big part. If people get to the moon, journalists will tell us, but there will always be a place for the good fiction writer. There is no kind of reporting that can do what a Tolstoy or a Dostoyevsky or Gogol did.

INTERVIEWER - Do you typewrite?

Eudora Welty - Yes, and that's useful. I can correct better if I see it in typescript. After that, I revise with scissors and pins. With pins you can shift things from the very beginning to the very end. Some things I let alone from first to last--the kernel of the story.

INTERVIEWER - And yet the most difficult thing would seem to be the hidden reaches of the human heart, the mystery, those impalpable emotions.

Welty - For a writer those things are what you start with. That's what makes a character, projects the plot. Because you write from the inside.

These interviews reflect the times they occurred. Learning how authors adjusted to writing techniques from pens to typewriters adds to the dimensions of the craft, and reading the essentials from successful story tellers makes my admiration for their talent even greater.

"Fascinating...This book will intrigue and delight any serious reader or writer. It may even inspire."

The Times Literary Supplement -

Apenas não gostei da conversa com Joan Didion, que me aborreceu tanto como o seu Ano do Pensamento Mágico.

Os entrevistados do volume 2:

1959 -

T. S. Eliot

1962 -

Ezra Pound

1960 -

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

1966 -

Harold Pinter

1967 -

Vladimir Nabokov

1978 -

Elizabeth Bishop

1984 -

Philip Roth

1987 -

Marguerite Yourcenar

1990 -

Iris Murdoch

1985 -

Primo Levi

1989 -

Jan Morris

2006 -

Joan Didion -

This is an amazing collection of interviews with a variety of writers, including several winners (or eventual winners) of the Nobel Prize for Literature, including

Toni Morrison,

Alice Munro,

Gabriel García Márquez,

William Faulkner, and

Isaac Bashevis Singer.

I also especially enjoyed the interviews with

James Baldwin and

Peter Carey who each discuss how they confront and address themes of identity, alienation and outsiderness.

There are a total of 16 lengthy interviews, and (please don't judge me) I didn't read them all. The interviews range in time from 1953 (

Graham Greene) to 2006 (

Stephen King). One game the reader can play is "spot the universal elements" — for example, many of these writers claim not to be influenced by trends, rules, or conventions.

Most interviews examine the art of fiction, but there is also a sprinkling of poetry (

Philip Larkin) and criticism (

Harold Bloom. Sometimes the reader is given glimpses of personal lives, a hint of the person behind the writing, but primarily the interviewers are focused on the creative process— and what a twisty unpredictable mysterious process that is! Being unconventional apparently is the norm. -

I would be hard-pressed to come up with the name of an author in this volume who was not grappling with the fear of losing his gift to age. There's a lot of wistfulness for youth and youthful work - and a lot of dread, too, about the futility of the craft, the broken dream. Then again, reaching a peak high enough to merit the attention of The Paris Review no doubt shakes the bones a bit. Here's one of literature's lifetime achievement awards, and is sure to startle the recipient into thinking: "Wait, wait...the career's not over, is it?" To a reader of these conversations, though, one right after another, the thrust of it all gets a little bleak. So, fair warning.

But let's quote a few of the less dread-filled passages, since they do exist:

William Faulkner:

No one is without Christianity, if we agree on what we mean by the word. It is every individual's individual code of behavior, by means of which he makes himself a better human being than his nature wants to be, if he followed his nature only. Whatever its symbol - cross or crescent or whatever - that symbol is man's reminder of his duty inside the human race. Its various allegories are the charts against which he measures himself and learns to know what he is. It cannot teach man to be good as the textbook teaches him mathematics. It shows him how to discover himself, evolve for himself a moral code and standard within his capacities and aspirations, by giving him a matchless example of suffering and sacrifice and the promise of hope.

John Gardner:

If you're in construction and building houses out of shingles and you realize that you're wiping out ten thousand acres of Canadian pine every year, you should ask yourself, Can I make it cheaper or as cheaply out of clay? Because clay is inexhaustible. Every place there's dirt. A construction owner should say, I don't have to be committed to this particular product: I can go for the one that will make me money and make a better civilization. Occasionally businessmen actually do that. The best will even settle for a profit cut. The same thing is true of writers - ultimately it comes down to, are you making or are you destroying? If you try very hard to create ways of living, create dreams of what is possible, then you win. If you don't, you may make a fortune in ten years, but you're not going to be read in twenty years, and that's that.

Stephen King:

The keepers of the idea of serious literature have a short list of authors who are going to be allowed inside, and too often that list is drawn from people who know people, who go to certain schools, who come up through certain channels of literature. And that's a very bad idea - it's constraining for the growth of literature. This is a critical time for American letters because it's under attack from so many other media: TV, movies, the Internet, and all the different ways we have of getting nonprint input to feed the imagination. Books, that old way of transmitting stories, are under attack. So when someone like Shirley Hazzard says, I don't need a reading list, the door slams shut on writers like George Pelecanos or Dennis Lehane. And when that happens, when those people are left out in the cold, you are losing a whole area of imagination.

Two volumes down, two to go. And the interviews continue... -

Read only the Graham Greene and James Baldwin interviews so far. The Baldwin one is quite good, worth the time. (The P.G. Wodehouse interview in Vol IV is a complete waste of time, sadly.)

May read some of the others eventually, but in no hurry to do so. -

As entrevistas da Paris Review nunca desiludem. A tendência é abordarem um autor e o conjunto da sua obra focando, uma vezes mais e outras menos, o seu processo de escrita, as suas leituras e autores de eleição, alguns dos textos e a vida de quem escreve. Destacam-se aqui três enormes conversas: com Philip Roth, Marguerite Yourcenar e Vladimir Nabokov. Mas, excetuando estas, não há nenhuma outra que seja menos interessante ou dispensável. Nota negativa para a entrevista a Céline, de quem se diz noutra entrevista que nunca despia a farda de cínico, e é verdade.

-

Another fascinating insight into the creative process: Peter Carey and Toni Morrison and, of course, the divine Ms Munro are a joy to read. Graham Greene is cool and ever so slightly prickly, Harold Bloom much sweeter than you might expect. It took me ages to finish only because I had no great desire to read the last interview, which is with Stephen King. But I did, just for the sake of finishing. Why does he think it necessary to defend popular literature? It doesn't need defending - by definition it has plenty of readers, so why?

-

A literal MINE. One to be read and re-read

I enjoyed everything until the last interview with John Gardener who loved his own voice so much. He said little and talked a lot. -

Even though the interview with Graham Greene was slightly disappointing and the one with William Faulkner showed him as quite arrogant - despite his writing being hailed by virtually every other author interviewed from the 1950s to the 1980s - there were quite a few eye-openers here.

Isaac Bashevis Singer's very subtle and very welcoming manners definitely lured me to examine his writing, and his view on forthcoming technology was definitely enough to have me drawn in.

Gabriel García Márquez was also quite humble, and made me wish to delve into his writing.

Speaking of which, a bunch of the authors in this volume refer to his "magical realism", a term I haven't come to grips with; other writers are also mentioned to adhere to this type of writing.

Philip Larkin, refusing to be interviewed in person, is here in print for one of the very few times he's been interviewed at all. He's witty, funny and very staunch. I love the way he views things, apart from how he dislikes modernism and thinks one jazz-musician killed jazz for all future. Still, Larkin didn't want to be named Poet Laureate for which I will always revere him, not to mention his style of writing and poems.

Harold Bloom and Toni Morrison both added inspiration and insight, but William Gaddis infused me with nothing. Alice Munro seems frank and easy-going, and Stephen King is...slighted by Stanley Kubrick, as always.

All in all: a very recommendable volume. Can't wait to get into the others!

I've screen-shot a bunch of pages from this volume, and they're viewable for your pleasure here.

http://issuu.com/pivic/docs/parisrevi... -

Reads like a vitamin B-12 shot...makes you feel vigorous and full of energy, after first feeling slightly uncomfortable.

-

Não li todas as entrevistas. Só as que me interessaram.

-

I cannot gush enough about these compilations. If you enjoy a candid interview with literary masters, then this is your cup of tea and then some. Faulkner, Welty, Toni Morrison, among many others. Truly, I savor each one and then return to read them again and discover something new every time. I want more, more!

-

SIX WORD REVIEW: A must-have for the literary apprenticehip.

-

http://miamisunpost.com/archives/2008...

Bound - Miami SunPost

Nov. 20, 2008

A Gentleman Among Men

George Plimpton Was All That and Then Some

By John Hood

George Plimpton and I first met at his Manhattan home back in ’90 or ’91 when he hosted a wedding reception for then Paris Review Senior Editor Fayette Hickox. I was just coming into my ego then and still a bit reticent around celebrity, but Plimpton made me feel immediately welcome into his world. That his world consisted of every 20th century writer of any merit, not to mention more bold-faced names than any three compendia on fame, only made his welcome all the warmer — and all the more cool.

The next day Plimpton had me up to his place again, this time so I could interview him for Paper Magazine, and again he insisted that I call him “George.” It wasn’t an easy move for me to make — his stature suggested a definite “Mr. Plimpton” — but he was adamant. Besides, George was simply too damn agreeable to argue with. We collided a couple more times over the years, most notably when Brian Antoni threw a Black & White Ball to celebrate the release of Truman Capote, and on each and every occasion George remained the consummate gentleman — impeccably mannered, effortlessly elegant and genuinely kind.

Of course I’m just one of the thousands upon thousands who encountered George throughout his long and robust life, and hardly one of his intimates. Had we been closer I’m sure I’d be among the many remembrances in the remarkable George, Being George (Random House, $30), an oral history that includes looks back from the likes of Gay Talese, Gore Vidal, William Styron and Peter Matthiessen.

Subtitled George Plimpton’s Life as Told, Admired, Deplored, and Envied by 200 Friends, Relatives, Lovers, Acquaintances, Rivals — and a Few Unappreciative Observers, and expertly edited by his pal Nelson W. Aldrich Jr., George is not just the sort of oral history very few people deserve, it’s the sort George himself would’ve definitely approved of. Why? Because it was a form he perfected with the books Edie and Truman Capote.

Yet neither Warhol’s tragic superstar nor the noted “non-fiction novelist” even came close to covering as much ground as George Plimpton, who was born with a silver spoon in his mouth, died the talk of the town, and in between lived enough lives to account for any 50 people, provided those 50 never stopped fully living throughout their entire lives.

I’m talking a man of action as well as letters, and quite often both at the same time. As a participatory journalist for Sports Illustrated, George went three rounds with then light heavyweight champ Archie Moore, quarterbacked the Detroit Lions, goaled for the Boston Bruins, hit the PGA Tour alongside Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, and flew through the air with the Clyde Beatty-Cole Brothers Circus. Each of those feats and more are talked about in George, some with envy, some with pride and all with utter awe.

But beyond the books and the exploits, George will perhaps be remembered for The Paris Review, which he helmed for the last 50-plus years of his life.

Founded in ’53 by Peter Matthiessen and Harold “Doc” Humes and basically given to George shortly thereafter, The Paris Review remains perhaps the most influential literary journal in history, mostly on account of its interviews, which began with E.M. Forster and number virtually every writer to have picked up a pen since.

Hemingway, Ellison, Faulkner, Greene, Burroughs, Miller, Bellow … name a 20th century heavyweight and The Paris Review chatted ‘em up. Some of those immortal interviews can now be found archived online, but to read them as they really were meant to be read, I wholeheartedly recommend you pick up Pantheon’s The Paris Review Interviews (Picador, $16).

Of the three volumes currently available, it’s impossible for me to pick a favorite, so I’ll just mention personal highlights from each.

In Volume I I’m most partial to James M. Cain, Richard Price and Dorothy Parker. Not because I don’t dig Borges and Bellow and Hemingway and Vonnegut (all of whom are also included), but because I double-dig crime and wisecracks, and if Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice and Price’s Clockers don’t epitomize crime writing and Parker wasn’t the embodiment of a wisecrack, then I’ll eat my hat.

For Volume II I’ll stick with Graham Greene and William Faulkner, first because of The Comedians and Our Man in Havana, and second because of As I Lay Dying and The Sound and the Fury, all of which I discovered back when I was broke and a book was all the sustenance I needed to get through a New York night.

In III I’ll take Raymond Carver, Norman Mailer and Martin Amis. Carver’s ultimately inimitable short stories still floor me, and on a couple occasions I got to meet Mailer, so his entry gets extra credit. Amis, I’m proud to say, I too had the privilege of interviewing.

And that kinda brings me full circle. Like George I believe in both word and action, and by George I’m inspired to fully use both. And while I might not do so with such grace and good manners, I’ve at least been given a blueprint. And so now have you. -

The Paris Review is een vierjaarlijks tijdschrift waarin naast korte verhalen en gedichten ook twee of meerdere interviews worden geplaatst met schrijvers van romans, korte verhalen, poëzie, essays en kritiek. Juist deze diepte-interviews (die vaak gehouden worden over meerdere sessies van enkele uren) geven helder inzicht in de drijfveren en werkwijzen van de geïnterviewde auteurs. In deze bundel zijn onder meer interviews opgenomen met William Faulkner, Graham Greene, Toni Morrison, Harold Bloom, Alice Munro, en James Baldwin. Of je de auteurs al kende of nog niets van hen hebt gelezen, elk interview is meer dan de moeite waard.

-

Another delightful installment of interviews with writers. Various notes:

-Harold Bloom is super full of himself.

-John Gardner seemed like a kindly old fellow, which made William Gaddis's spite towards him even more amusing.

-William Gaddis: full of spite. But sort of an awesome dude.

-I kinda want to read some Philip Larkin and Peter Carey after reading their interviews. Maybe Alice Munro, too.

-Robert Lowell cracks me up.

So yeah, a fine read. On to Vol. III, or one of the other books I'm reading. -

If you read fiction or want to make more art, read this. Faulkners spicy take on an artist's commitment to art will motivate anyone who wants to create more. Stephen King's breakdown on the disconnect one must take between the process of creating and the final product is so good. These books are perfect to go to bed to. These books are way less highbrow than the topic would seem, most of these artist are just crazy ass people with cool stories and life experiences.

-

I just can’t say enough about this series of interview collections. They are all filled with fascinating discussions with great writers. Harold Bloom’s incredibly erudite and controversial interview was my favorite in this volume. I feel the need to read everything he ever wrote after reading this, except maybe the J Author biblical book. Oh, but maybe Faulkner’s was even better. And I forgot Philip Larkin’s too.

-

There are so many good interviews in this selection, so much good advice and fun. I cannot pick one interview that I liked more than another. I might add that Stephen King (although not one of my favorite writers) killed me with his interview. This is a guy that I would pay money to hang out with for a day. He knows his stuff without sounding arrogant.

-

Wisdom indeed! I ended up reading all of these interviews, not just the ones with writers I knew, because they were all so interesting and thoughtful in their own ways. Was introduced to a hell of a lot of new titles, and read a gazillion poems by people I'd never even heard about before, shamefully enough. (Hart Crane, you now have my heart.)

-

I read this for Faulkner, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Toni Morrison. If you only read these 3 the book is worth it. Morrison's interview is one of the greatest I've seen—practical advice, relevant conversation, and you get to see a true, honest, intelligent mind at work.

Faulkner's kinda fucked up, but worth reading. -

大概用了2-3周看完这本访谈集,就像第一本那样引人入胜。我时常觉得书评写起来是无趣的,谈起来更有意思

-

The great writers of our era speaking in their own words and their own voices, without any fictional characters getting in the way. An incredible lineup of authors interviewed and an absolute treasure trove for young and aspiring writers. An irresistible source of inside knowledge about your favorite authors and there's something for everyone. The biggest of names; William Faulkner, Gabriel García Márquez, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison. The lesser known: James Thurber, Eudora Welty, Philip Larkin. The verbose Harold Bloom and Robert Lowell, the terse Graham Greene, the seemingly regular folk Alice Munro and Stephen King, the unknown (to me) Peter Carey. And more (I.B. Singer, John Gardner, William Gaddis). Gossipy, knowledgeable, opinionated, wise, these interviews reveals rarely seen facets of these authors and their words tell much more than they may have expected. Some are private and guarded, some can't hold back, but all have something of interest. [5★]

-

Excellent.

//A mostly lovely and enthralling insight into the lives of 17 diverse writers, starting in 1953 with Graham Greene and working through to Steven King in 2006. Without a doubt, the interviewers the Paris Review put up to these are the best I've seen— the questions are graceful, brave, very well-informed and switch viewpoints often, capturing the personalities from a variety of angles. Each interview does contain some shop-talk about writing routines, preparation and mechanics which is interesting on its own, but the bulk of the material is a lot more personal questions: Gabriel García Márquez's writing evolutions during the riots in late 1940's Columbia, James Baldwin dragging himself out of New York City, Faulkner's rewritings of The Sound and the Fury, each from the viewpoint of a different character,

Toni Morrison's insistence on entirely imagined characters, Alice Munro's bookstore, and on.

Not every writer read, needed, eh.

//The more excellent is that you really don't have to be familiar with every writer's work to enjoy this book. Of course, I mostly picked this up because I was interested in the people I had read talk about writing and reading and their process, but the others that I hadn't read were just as interesting.

Very few dragging parts.

//Only one bore, drag-ass chapter: Harold Bloom. I like literary criticism even. But the Bloom interview was dreadful.

Overall, super valuable. About the perfect length. Little introductions to the writers, talking about their homes (if they were interviewed there) how each one spoke, little quirks, etc. Recommended. -

I finally finished reading this great book. It is a compilation of interviews with well-known authors of the 20th century including Faulkner, Graham Greene, Toni Morrison, and Stephen King. Of course, those were amazing interviews, but I even enjoyed the ones with authors I haven't read. What struck me most is the discipline and drive they all had to write and the conditions that they preferred to write under. Also, it was interesting to find that some of them had insecurities. Many of them explained they had done a lot of writing before they were published that they deemed to have been crap. Most of them seem to have been most successful midcareer, and also said they were slowing down in their sixties, but couldn't stop writing. Finally, there were varying degrees of control or calculation on the part of writers. The most successful seemed deeply compelled to write didn't tend to teach alot, and were less calculating about what thye would write except for Toni Morrison. All of them expressed an amazingly accurate awareness of their importance and message as writers with alot of humility and good humor. None of the good ones really cared about the critics.

As a side note, I learned that Alice Munro set up Munro's books with her ex-husband in Victoria, BC - the first good book store in which I spent any time.

The most surprisingly fun and interesting interview was with Harold Bloom - he's quite a card. -

By chance I picked up the Winter Issue of the Paris Review, and so intrigued by the interview with Ha Jin I bought this edition. These interviews are gems.

I had no idea how arrogant William Faulkner was.

Isaac B. Singer sounds like the grandfather I never had but always wanted.

I rarely agree with Toni Morrison's take on things. 1)

And Alice Munro is much more interesting in her stories than in her interview. Which is just the way it is supposed to be.

Now I'll go buy another edition of the interviews.

Annex 1) But when I do it couldn't be stronger as with this quote:

"It is not possible for me to be unaware of the incredible violence, the willful ignorance, the hunger for other people’s pain. I’m always conscious of that though I am less aware of it under certain circumstances – good friends at dinner, other books. Teaching makes a big difference, but that is not enough. Teaching could make me into someone who is complacent, unaware, rather than part of the solution. So what makes me feel as though I belong here out in this world is not the teacher, not the mother, not the lover, but what goes on in my mind when I am writing. Then I belong here and then all of the things that are disparate and irreconcilable can be useful." -

There are many elements to interviews, such as:

a) The interviewer's questions,

b) The willingness, or the unwillingness, of the person being interviewed,

c) The interviewee's ability to hold an interesting conversation,

d) The interviewee's way of dealing with the flattery of being interviewed,

e) The interviewee's articulation or lack thereof on the topic at hand--writing, in this case,

f) The interviewee's superstition of discussing writing,

g) How given to posturing the interviewee is.

Etcetera.

So, a collection of interviews can never be consistent, but this is one of the best collections I've seen. Some of them aren't about writing at all, some of them are charming, some of them are ugly and hateful, some of them are actually informative. I can't manage to read them all in one go, but the stand-outs in this collection for me so far are Alice Munro and

Toni Morrison. James Thurber was less informative but still very enjoyable.