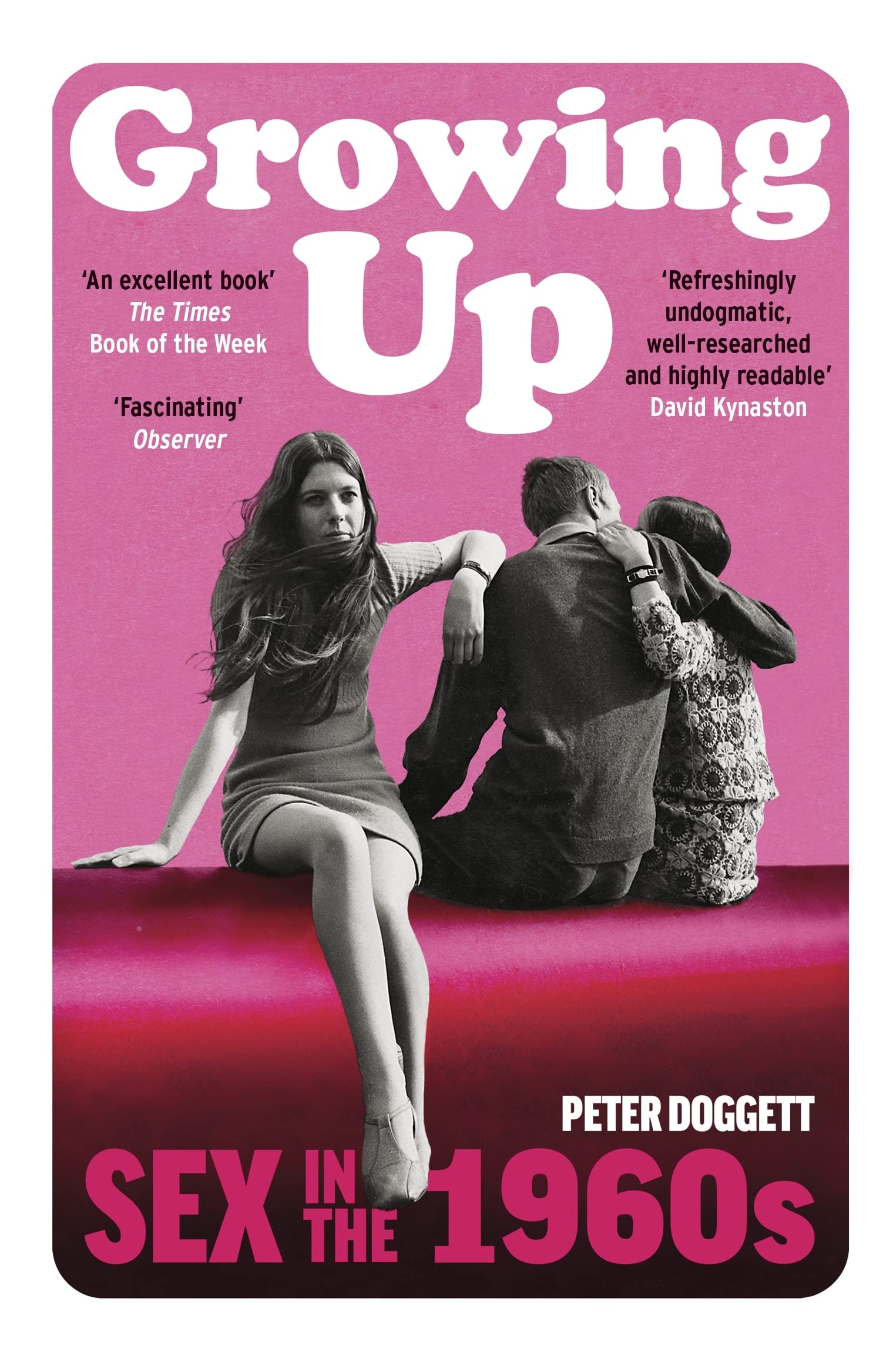

| Title | : | Growing Up: Sex in the Sixties |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1473547261 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781473547261 |

| Format Type | : | ebook |

| Number of Pages | : | - |

| Publication | : | Published November 4, 2021 |

No era in recent history has been both more celebrated and vilified than the 1960s. And at the heart of all that controversy - the music, drugs, fashion, hopes, dreams and political movements - is sex.

In this wide-ranging and eye-opening survey of the sexual landscape of the 1960s, Peter Doggett has assembled a dozen little-known stories that reveal how the sexual revolution transformed people's lives - for better or worse.

'An important reappraisal of a decade that changed us, for good and ill' Sunday Times

'Fascinating...shows rather conclusively that the sixties was not a sexual paradise' Evening Standard

'Creates an account of the 1960s that, unlike most popular histories, does not edit out the grim bits' Mail on Sunday

Growing Up: Sex in the Sixties Reviews

-

Britain in 1960 was still a country that belonged to its past and a time traveller from the 1930s would have felt very much at home there. However, Britain in 1970 had become a country that looked to the future with great optimism and really seemed to be a modern place that was busily casting off the shackles of its upright, censorious past. Peter Doggett’s Growing Up: Sex In The Sixties casts a jaundiced eye over the decade and argues that it was all very bad indeed. That is not to say that Doggett is a full-blown fan of Mary Whitehouse, but he does treat her with far more respect than she ever deserved.

The 1960s was a disruptive decade where the future collided violently with the past, and the future won hands-down. That victory owed a lot to the contraceptive pill that was introduced in 1961. If you want to know why the sixties swung, much of it was due to the fact that young women could let their hair down without fear of their actions having any untoward consequences. Doggett does not mention that crucial point in his work. Instead, he seems to take the view that women were the victims of the decade, instead of being liberated by it.

Growing Up is divided into twelve chapters, and three of them are devoted to looking for, and finding very dubious evidence of the growth of underage sex. Most of these chapters are concerned with Vladimir Nabokov’s novel, Lolita, which was first published in the UK in 1959 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, a publishing house not noted for pornography. The publication was controversial, but no attempt was made to prosecute the publishers; that had to wait until 1960 when Penguin was unsuccessfully prosecuted for publishing Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Lolita was left alone because there are no sex scenes in it, unlike Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Both novels are fine literature, but Lolita is one of the greatest works of the twentieth century, and even the Director of Public Prosecutions wasn’t going to go up against a literary work, published in hardback by a major house, which had the support of most of the literary figures of the day. The DPP was foolish the following year, but the prosecution of Lady Chatterley’s Lover might just have succeeded, but there was no way that it would have washed with Lolita.

It is hardly Nabokov’s fault that the title of his novel became a codeword for underage sex. Had Lolita never been written then something else would have emerged to provide the keyword that putative punters of such material would use to find what they were looking for. The growth of underground pornography of all types in the sixties owed very little to Nabokov and a lot to another bit of disruptive technology, in this case, the Xerox 914 photocopier that was introduced in 1959.

It was a brute of a machine that weighed a hernia inducing 648 pounds which is just less than 300 kilos, but it was a gift to the Soho publishing trade that until then had relied on Gestener duplicating machines. The one-man aficionados of a particular kink also took advantage of the Xerox 914 to increase the output of their newsletters which they advertised in magazines such as Exchange & Mart. The machines were very expensive, but plenty of companies set up shop to cater for small businesses that needed photocopies and in Soho especially, they were not too interested in what they copied so long as payments were made in cash. I would be more inclined to give weight to Xerox for the growth of underground pornography, rather than Nabokov to be honest.

From young girls, Doggett moves to young women, who are little more than the victims in his eyes of men’s wickedness. He has hunted down a series of fairly nasty murders and assaults and presents these as somehow typifying the decade. Actually, far more typical of the period was the power of women to control their own fertility that the contraceptive pill gave them, coupled with the liberation of Vidal Sassoon’s geometric hair cut, the miniskirt and the confidence that young women had to throw off their mother’s iron perms and passion killing corsets.

Homosexuals were also victims in this period according to Doggett who devotes far too much space to people who were peddling cures for that predilection. Yes, they existed, but by the end of the decade, homosexuality had not only been decriminalized, but pubs and nightclubs that were known to cater to a homosexual clientele were operating with only minimal interference from the police or the licensing magistrates.

The problem with disruptive eras is that they are untidy and often chaotic and the sixties had all that in spades. Yet, by the end of the decade, Britain was groping towards a new consensus where adults felt much freer socially than they had at the start of the period. Peter Doggett ignores the social liberation that became accepted after the decade, and concentrates only on the reactions to it during the era.

For that reason, his work is more an example of present-day woke beliefs rather than a serious contribution to the historiography of the 1960s.

An edited version of this review has appeared in The Brazen Head, an online political and literary quarterly journal.

https://brazen-head.org/ -

– Reify

– Tawdry

– Inviolability

– Tendresse

– Impiousness

– Diffident

– Insouciance

– Rapacious

– Priapic

– Ineluctable

– Cognoscenti

– Samizdat

– Heterodoxy

– Mellifluous

– Cabal

– Paean

– Roman-a-cléf (Fear and Loathing/On the Road)

– Atonal

– Traduced

– Onanistic

– Louche

– Nouvelle Vague (Jean Luc-Godard)