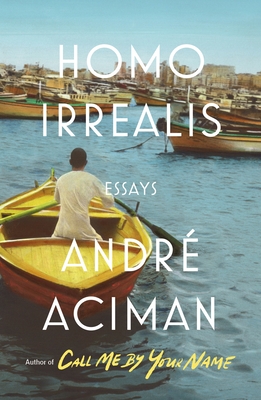

| Title | : | Homo Irrealis: Essays |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0374171874 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780374171872 |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 256 |

| Publication | : | First published January 19, 2021 |

| Awards | : | PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay Shortlist (2022) |

Irrealis moods are a category of verbal moods that indicate that certain events have not happened, may never happen, or should or must or are indeed desired to happen, but for which there is no indication that they will ever happen. Irrealis moods are also known as counterfactual moods and include the conditional, the subjunctive, the optative, and the imperative--all best expressed in this book as the might-be and the might-have-been.

One of the great prose stylists of his generation, Andr� Aciman returns to the essay form in Homo Irrealis to explore what time means to artists who cannot grasp life in the present. Irrealis moods are not about the present or the past or the future; they are about what might have been but never was but could in theory still happen. From meditations on subway poetry and the temporal resonances of an empty Italian street to considerations of the lives and work of Sigmund Freud, C. P. Cavafy, W. G. Sebald, John Sloan, �ric Rohmer, Marcel Proust, and Fernando Pessoa and portraits of cities such as Alexandria and St. Petersburg, Homo Irrealis is a deep reflection on the imagination's power to forge a zone outside of time's intractable hold.

Homo Irrealis: Essays Reviews

-

I am the gap between what I am and what I am not.

Even before the essays – beautiful, wise, full yet strangely wistful – begin to sing, this quote of the maverick Fernando Pessoa finds place. And that rounds up the mood of the collection. Irrealis mood. And it might not have sounded louder in any tunnel of time than of right now; now, when our smallest of desires suffocate between the walls of a world we are no longer able to recognize.

Why do we feel a freefall of emotions seeing a stranger couple on the silver screen? Why should a piece of music imagined by someone else take us to a place that is both theirs and ours? How the touch of an unknown warrior triggers a pain in us that throbs with a shared intensity? Perhaps, it is these ambiguous spaces within which we live.Ambiguity in art is nothing more than an invitation to think, to risk, to intuit what is perhaps in us as well, and was always in us, and may be more in us than in the work itself, or in the work because of us, or conversely, in us now because of the work. The inability to distinguish these strands is not incidental to art; it is art.

Meditating on a life that has seen displacement but also identity, upheaval but also healing, André Aciman talks about people who made the journey interesting, often granting him a patch of sunshine but also teasing his heart with the magic of early winter breeze – Claude Monet, Sigmund Freud, C P Cavafy, W G Sebald, John Sloan, Éric Rohmer, Fyodor Dostoevsky, James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Ludwig van Beethoven, Fernando Pessoa. In between the brief felicities of is and could have been, he made his life. And I felt, I could too. Because I don’t know a single day when I haven’t cast shadows on a place I wish to be. Because I am devoid of days when a conversation has not unfurled in my mind that could not find its real formation.

I realized, like a reaffirmation, that what books and notes, people and posterity document are as much my truth as those that find no record. And all the art in the world is my canvas to write that unrecorded part of my being.

In these times of anxiety, in Aciman’s ruminations, like a friend bumped into after a hiatus, I found much solace and joy. Should you need a friend, know this gentleman comes with my recommendation. What’s more? He might tell you a thing or two about me!

------

Because I found such dazzling beauty in this collection, I am sharing some for your sumptuous smothering:

Remanence is the retention of residual magnetism in an object long after the external magnetic force has been removed. Remanence is the memory of something that has vanished and left no trace of itself but that, like a missing limb, continues to exert its presence. The water is gone, but the dowsing rod responds to earth’s memory of water.

They continue to hover over the city like the ghost of unfledged desires that forgot to die and stayed alive without me, despite me. Each Rome I’ve known seems to drift or burrow into the next, but none goes away.

I spotted one store that sold a product you find in every gift shop in St. Petersburg: colorful, high-end matryoshka dolls. The painted wooden dolls of increasing size nested one inside the other provide a metaphor for everything here: one regime, one leader, one period nested in the other, or, as Dostoevsky is rumored to have said, one writer coming out of another’s overcoat pocket.

Beethoven will keep repeating and extending the process until it is reduced to its barest elements and he’s left with five notes, three notes, one note, no note, no breath. The fullness of the absence after the final notes is the whole point, and he’s fearless in making us hear it. And may be all art strives just for that, life without death. The greatest art – Beethoven’s soundless last note, Joyce’s snow, the Proustian sentence that enacts the paradox of time – peers squarely into the unfathomable: the mystery of not being there to know we’re already absent. -

Irrealism is a term that has been used by various writers in the fields of philosophy, literature, and art to denote specific modes of unreality and/or the problems in concretely defining reality.

These essays were quite literary and covered the range of art, literature, cinema and memoir. Place and time.

Enjoyed some, some I felt lost in, like I was being consumed by the irrealis. His life in Egypt, France walking through Rome, St Petersburg. Enjoyed the part on Sebald and enjoyed the authors enthusiasm for each subject whether a painting, a poem, watching a movie in the cinema.

I took this slow, there is much to consume, ponder. A mixed read for me but an interesting one.

ARC from Netgalley -

Well, André Aciman’s latest essay collection is certainly more intellectually bracing than his fiction, especially the rather tepid ‘Find Me’. Whether or not this will appeal to the average reader of ‘Call Me By Your Name’ remains to be seen.

‘Homo Irrealis’ is a play on the linguistics term ‘irrealis’, which Aciman defines as per its Wikipedia entry, “because the Oxford English Dictionary does not house the word.” He explains that “the irrealis mood knows no boundaries between what is and what isn’t, between what happened and what won’t.”

As an example, Aciman references his ‘many worlds’ immigrant experience: What happened to the person I was actually working on becoming but didn’t know I was about to become, because one never quite knows that one is indeed working on becoming anyone?

If this sounds far more complicated than it should be, Aciman does relax a bit as the essays progress. Probably the best is the candid ‘In Freud’s Shadow, Part 2’, where he recounts as a schoolboy frequenting a large remainders bookstore on the Piazza di San Silvestro in Rome, ferreting out a copy of ‘Psychopathia Sexualis’ by Richard von Krafft-Ebing.

One would think that haunting bookshops to get a glimpse of salacious reading is practically a guarantee of sexual dysfunction later in life. Well, some critics have frowned at the age difference in ‘Call Me By Your Name’, as well as at the old man/young woman section in ‘Find Me’. However, is this a surefire indication of pathology, or just wishful thinking on the part of cancel culture?

One afternoon after leaving the bookstore, Aciman as a schoolboy takes the 85 bus. This is crowded, which results in a young man being pushed up against him from behind and grabbing his upper arms as well to steady himself. The encounter is almost unbearably erotic to the lonely Aciman, and becomes a mental lacuna that he spends his entire life excavating and refilling, like sand in an hourglass:

Now, whenever I come to Rome, I promise to take the 85 bus at more or less the same time in the evening to try to turn the clock back to relive that evening and see who I was and what I craved in those days.

That is the ‘irrealis mood’ at its most plangent. If you think this is an early indication of homosexual tendencies in Aciman, the reality is far more complicated. He subsumes his erotic fantasies of the young man on the 85 bus with his lustful pining after Gina, who “smelled of incense and chamomile, of ancient wooden drawers and unwashed hair…” This results in a kind of polymorphous frenzy that must have driven the young Aciman wild with unrequited desire:

Night after night, I would drift from him to her, back to him and then her, each feeding off the other and, like Roman buildings of all ages snuggling into, on top of, under, and against each other, body parts stripped from his body were given over to hers and then back to his with body parts from hers.

One wonders how encounters such as these must have fed into Aciman’s literary imagination, becoming grist for novels like ‘Call Me By Your Name’, which is practically brimming over with the irrealis mood. I am also reminded of ‘The Motion of Light in Water’, wherein Samuel R. Delany writes powerfully about the refractive effect of memory.

Aciman certainly can’t quite summon the same playful, transgressive and libidinous tone of Delany in full linguistic flight. Indeed, there is something almost strained about ‘In Freud’s Shadow, Part 2’. The author is on far more familiar ground when he waxes lyrical about art, cities and famous writers. This seems to give him the necessary distance in which to examine both his thoughts and desires with the necessary dispassion. An example is Aciman’s postcard of the Apollo Sauroktonos statue in the Vatican Museum, which is like a message from a younger to an older self:

All I had at home was my picture of the Sauroktonos. Chaste and chastening, the ultimate androgyne, obscene because he lets you cradle the filthiest thoughts but won’t approve or consent to them and makes you feel dirty for even nursing them. The picture was the next best thing to the young man on the bus. I treasured it and used it as a bookmark. -

I would give this 4.5 stars just because some essays I enjoyed more than others, but I'm overall thankful for having encountered this book that gave a voice to some inner thoughts. In retrospection, "I have always felt as if I had no place in reality, as if I were not there at all." And if you've ever felt the same, you should read this book.

In this essay collection, André Aciman uses various forms of art - cinema, literature, poetry, painting, sculpture, architecture - to examine the concept of the irrealis mood. Here are two attempts to explain the irrealis mood by using the author's words: 1) "It's not about what did not, will not occur, but about what could still but might never occur" and 2) "might-have-beens that haven't really happened but aren't unreal for not happening and might still happen, though we hope - and fear - they both will and never will happen."

This book reads as the midnight thoughts that creep in our minds uninvited, making us question everything - our place in the world, our path, our interpretation of our life, the concept of time. "If time exists at all, it operates on several planes simultaneously, where foresight and hindsight, prospection and retrospection are continuously coincident," explains Aciman.

As humans we often wonder if we live the life we should, if we took the right path. "So many of us don't really belong here - not in the present, or the past, or the future - but all of us seek a life that exists elsewhere in time, or elsewhere on-screen, and that, not being able to find it, we have all learned to make do with what life throws are way." But even though we make do with what we have, we never really forget the life we imagined we should have. "The life we're still owed and cannot live transcends and outlasts everything, because it is part yearned for, part remembered, and part imagined, and it cannot die and it cannot go away because it never, ever really was."

This book will also make you consider how much time alters memories. "Whatever it is I am trying to preserve may not be entirely real, but it isn't altogether false." That in actuality "we remember best what never happened" and that "the feelings that hurt the most, the emotions that sting most, are those that are absurd: the longing for the impossible things, precisely because they are impossible; nostalgia for what never was; the desire for what could have been; regret over not being someone else, dissatisfaction with the world's existence." -

Aciman lacks the depths to be an essayist. His concept is interesting, but his writing is short of critical insights. You would think that a contemporary Alexandrian writer could see Cavafy in a new light, but the essay on Cavafy focuses on a poem that is almost a Cavafian cliche and manages to say nothing original about Cafavy at all. The same is true of Aciman's essay on Sebald. Could there be a writer more suited to the melancholic realm of homo irrealis and Aciman's theme? Even here, Aciman fails -- not a mention of The Rings of Saturn and that book's quest for imaginary reality and the nighttime world of Sir Thomas Browne. Instead, Aciman is content to write about Sebald's connection to the Holocaust. Very simply, the essays lack critical scope. By the end of the book, Aciman is running out of steam and he pads the volume with a dull essay on the nature of endings in writing and music. He turns to a souffle metaphor and in doing so describes this book perfectly -- a set of ideas filled with verbosity and hot air.

-

This collection of essays by André Aciman is highly intriguing that I spent my entire weekend digesting his thoughts of the irrealis form of thinking that most of us possess, and sometimes we express unconsciously.

In linguistics, “irrealis” moods are the set of grammatical moods that indicate that something is not actually the case or that a certain situation or action is not known to have happened at the moment the speaker is talking.

What the author transcribes as irrealis is how we often think in the form of “what should we have done” and the kind of longing for the alternate universe that might accompany us were we put that choice up instead of the choice that we finally ended up making. There are many ways irrealis moods could influence us, and it’s the author’s gift for having lived in various places around the globe, reading many classical books, as well as watching countless films that enable this thought to transpire in him. It all begins in his quest of searching for the real Alexandria, the place which rejected him due to his Jewish heritage, and the fact that he longed for that Alexandria which never was by the time he moved to Rome.The irrealis mood knows no boundaries between what is and what isn’t, between what happened and what won’t. In more ways than one, the essays about the artists, writers, and great minds gathered in this volume may have nothing to do with who I am, or who they were, and my reading of them may be entirely erroneous. But I misread them the better to read myself.

From the start of the volume, the author has warned the readers about the implications of reading through the lens of irrealis mood. What we call reality, experience, or senses might as well disappear in the face of the irrealis mood. And there’s no better way to get in touch with irrealis mood besides facing it inside works of art. In this volume besides from his own personal experiences, the author also provides us with the irrealis mood that he "thinks” present inside Freud’s sojourn to Rome, three French New Wave films directed by Eric Rohmer (My Night at Maud’s, Claire’s Knee and Chloe in the Afternoon), paintings by the Impressionists, as well as Proust’s novel. His reading through those works never failed to impress me on how the irrealis mood is pretty much present in many art forms.

By the time I reached the last essay, it gives me an impression that we as humans have never truly lived in the present. There are many ways we reject reality by thinking of “what could possibly happen if…” and present ourselves with so many alternative cases. And that’s why we ended up inventing words such as 'remorse' and 'regret' to cope up with the daunting irrealis mood. Much more so, André Aciman uses many of his personal experiences that seem at times coherent with my own in the way that I interpret them as so. Perhaps we all have become slaves to probability.

This volume will be really engaging if you are a fan of art and literary essays, and have a general understanding of New Wave French cinema which occupies almost half of the volume. Through this volume, the author takes me on a journey to see that our lives might have been guided through so many random occurrences and serendipities more than what we realise.

===

I received the Advance Reader Copy from Farrar, Straus and Giroux through NetGalley in exchange for an honest review. -

i don't know how i feel about this. some of the essays made me feel stupid, but andré aciman's style is very pretty. i enjoyed reading it even if i barely understood anything.

-

A book of essays reflecting the author's nostalgia for places and experiences in his past. Alexandria, Paris and New York City are prominent., with a side trip to St. Petersburg. Aciman's interests are with the essences of literature, art and film, and how these impact on one's sense of being and belonging.

My personal favorites were with his takes on Sebald and Pessoa and what they reveal about that strange state of being he calls the "irrealis mood...of our fantasy life, the mood where we can shamelessly envision what might be, should be, could have been, who we ourselves wished we really were if only we knew the open sesame to what might otherwise have been our true lives. Irrealis moods are about the sixth sense that lets us guess and, through art sometines, helps us intuit what our senses aren't always aware of. We fit through wisps of tenses and moods because in these drifts that seem to take us away from what is around us, we glimpse life, not as it's being lived or was lived but as it was meant to be and should have been lived."

He quotes Pessoa: "there's a thin sheet of glass between me and life. However clearly I see and understand life, I can't touch it."

It is these mysteries of life that define our lives and that draw us to fiction and art for they imagine what life could be. -

Definitely a dense read... hence the amount of time this took me to finally finish BUT i really liked the ideas in here (I feel like it put into words random thoughts I’ve had as of recent and it was oddly satisfying)

-

Almost there but it wasn't.

-

"We remember best what never happened."

-page 60

Homo Irrealis, the latest essay collection from Andre Aciman is about the fine balance between here and there, a feeling of something that has not yet happened but there is no certainty whether it will or won't. Dreams and longings that reality never lives up to. Waking up in a hotel room in a foreign city with the anticipation of discovery, a day where everything ahead is new and unknown; a moment of intimacy between two people before real intimacy; a flicker of flirtation - all the themes that are present in his novels as well.

The essays are about those subtleties, about how this in-between feeling, sensation, this irrealis manifests in movies, cities, relationships, books, memories. They are not all equally good and perhaps some lack a deeper insight but despite that I really enjoyed them. Aciman writes about nostalgia like no one else and that's what makes his work so irresistible. It makes me long for something unfamiliar, an uncharted territory where I have been in another lifetime. It's bitter and sweet, this feeling. Like a travel memory you revisit in your head knowing that going back to that place will only result in disappointment because this fleeting moment can only be recreated in your own head, it is ungraspable. -

While I enjoyed the philosophy of the book, some of the essays were not engaging enough to keep my attention. This book is a much slower read than anticipated. It was conceptually interesting but just did not have the writing style or character development needed to bring these ideas to life.

-

If someone were able to feed all my dream aesthetics and literary interests and the thoughts that plague me when I am in the midst of a fit of nostalgia-infused melancholy and produce the perfect book for a person like me (or at least the person I aspire to be), it would definitely be a "Homo Irrealis". This is a well-written, well-argued collection of essays about some of Aciman's favorite creators and the literature and art that has haunted him throughout his life. A certain familiarity with the people in question (though not their entire artistic production) might make this more interesting to a reader, but I don't think it's a requirement to enjoying this book.

Aciman being who he is, he is less interested in the facts or plot details and more in sensations, and more importantly, the sensations that each work evokes in him. And in all honesty, that is one of my favorite type of criticism: the one that provides historical and artistic context for each work, but then delves in to the sensations, memories, feelings that it has produced in the reader. I find those types of essays far more illuminating, or at least more entertaining.

I do think the introduction is the pièce de resistance of this entire collection, not least because it makes an argument for nostalgia not as something that we feel towards the past as it was, but rather about the future that could have been, when we longed for things to change and for us to be happier, more like ourselves in another place, in other circumstances.

Still, if you like Aciman's style, maybe first check the table of contents to see how interested you are in the authors he discusses, but definitely don't miss out on this. -

'However you look at things, everything always already happened, will happen, might, could, should happen. You never planned for next year; that was being presumptuous. Instead, you planned to remember. You even planned to remember planning to remember.' (p.70)

'I look at places that no longer exist, at constructions that have long been torn down, at journeys never taken, at the life we're still owed and for all we know is yet to come, and suddenly I know that, even with nothing to go on, I've firmed up something if only by imagining that it might happen. I look for things that I know aren't quite there yet, for the same reason that I refuse to finish a sentence, hoping that by avoiding the period, I'm allowing something lurking in the wings to reveal itself. I look for ambiguities, because in ambiguity I find the nebulae of things, things that have not yet come about, or, alternatively, that have once been but continue to radiate long after they're gone. In these I find my spot of time, my might-have-been life that hasn't really happened but isn't unreal for not happening and that might still happen, though I fear it may not come in this lifetime. (p.26)

'What happened to the person I was actually working on becoming but didn't know I was about to become, because one never quite knows that one is indeed working on becoming anyone? (p.12) -

The book jacket says André Aciman is “one of the great prose stylists of his generation”. I now know what a “prose stylist” means. The book is best for its many beautiful sentences. I get the author’s fluid “verbal moods”. In an irreali mood, you are in the past and future but never the present. Your nostalgia is for something that never happened, and you think of a future when you can safely look back at the present, etc…etc.. All those beautiful, strangely twisted moods are presented through his reading of Proust, Freud, Eric Rohmer, etc.., which sometimes gets lost in me.

The gossip girl in me tries to figure out whether André Aciman is gay. Looks like he is bisexual: his sexual awakening was triggered by a man, but in the next chapter he was heartbroken by a woman. -

I couldn't finish it. The first essay was really good but the rest were way too stretched out.

-

the discussion of time in the mindfuck koncepti gave me very much ✨nolan✨

-

3.8

I do truly love Andre’s writing. -

( he s just like me fr) about longing for the good place, mostly imagined, sometimes real.

I always learn so much about people from history Proust, Monet, Dostoevsky, Beethoven and some how Mendeleev. i never know what to expect from his essays i always come out with more information about cultural icons but also him and his life portrayed in such a way that is very relatable thru his overthinking, living in dreams and what ifs.

“Caught between the no more and not yet, between maybe and already, or between never and always, the irrealis mood has no tale to tell—no plot, no narrative, just the intractable hum of desire, fantasy, memory and time. The irrealis mood can’t really even be written in, much less thought in. But it’s where we live,”

“I remember a place from which I liked to imagine being already elsewhere. To remember Alexandria without remembering myself longing for Paris in Alexandria is to remember wrongly,”

“the first week of a new love,” when “everything about the new person seems miraculous, down to the new phone number, which is still difficult to remember and which I don’t want to learn for fear it might lose its luster and stirring novelty.”

”we remember best what never happened.” -

"The might-have-been that never happened but isn't unreal for not happening and might still happen, though we fear it never will and sometimes wish it won't happen or not quite yet."

An essential collection of essays written in the most metafictional, meta-analytical and metaphorical prose.

André Aciman at his finest.

Words the author explores in these essays: pénétration, happenstance, white nights, amour-propre, symmetrical reversal, moto perpetuo, almost, irreality.

Works explored, in order of appearance: Selwyn's "The Emmigrants"; Freud's "Civilisation and Its Discontents"; Goethe's "Halian Journey"; Phillips's "Heaven" poem; "Rip Van Winkle"; Rohmer's "Maud" film/play; Monet's "Poppy Fields" painting; Pessoa's "Book of Disquiet".

If any of these caught your attention, go give this brief collection of essays a try! -

André Aciman es un autor que me gusta.

Hay algunos ensayos que me gustaron mas que otros, pero no por eso lo voy a crucificar.

Es interesante como viaja entre varias formas del arte al escribir, literatura, cine, poesía, arquitectura, pintura.

Lei la version original, no se si tiene traducción al español.

Es una lectura interesante. -

skvělý to bylo

-

Some interesting concepts but very lofty and repetitive

-

Just Andre repeating the same thing for 238 pages straight.

-

Two words: holy shit.

-

This book of essays could be one sentence long and still convey about as much meaning as it does in 238 pages. Things change, we make choices and the road not taken becomes a second, irreal reality existing alongside our actual lives. The third to last essay was fittingly called “Almost there” as in you are finally almost done reading this. It doesn’t surprise me that Aciman loves Freud and Rohmer

-

(c/p from my review on TheStoryGraph) I can't tell if it is the themes of this book that I don't like or if it is the writing or the fact that I cannot handle this much serious reflection on Freud, a man I dislike with a deep intensity. It's a shame because the introduction had me really interested but the essays themselves didn't hit at all. They could have, the bones were there, but somehow none of them worked as well as I sort of hoped they would. Instead I was either bored or annoyed or both. I think at this point Call Me By Your Name is easily this authors best work. I don't know why the rest of his works don't hit except maybe there is an almost aggressive intellectualism if that makes sense. There is an idea that the reader understands everything the author is referencing and knows all the historical and cultural beats. I remember in Find Me being annoyed that he would use other languages as if the readers all speak Italian and French. There is a "if you don't get it you shouldn't be reading this" vibe to his later work that doesn't sit with me. I don't know how much more of a try I'm gonna give this author. Which is a shame because his prose can be extremely lovely.

-

Aciman takes us on a journey through his boyhood in Alexandria to his longing for France that we’ve all felt at least once in our lives to the hustle and bustle of New York that leads to periodic introspection. Homo Irrealis takes things that I had an interest in and analyzes them through a lens that I wish to eventually develop. Essays range in topics from Freud in Rome to Rohmer and Proust to Dostoevsky in St. Petersburg, but always keep the theme of irrealis: things that could have been but might not happen. Fans of Aciman’s previous works will be familiar with this theme. It lines Elio’s reflective thoughts in Call Me By Your Name and was exactly what I expected from this collection of essays. Another mainstay of Aciman’s work that I have to mention is his beautiful prose. Even in nonfiction essays, Aciman finds a way to make everything beautiful. There were moments while reading this where I had to pause and think about the beauty of what I had just read. No one arranges words quite like André Aciman. If you’re a fan of Aciman or looking to become one, you will certainly enjoy Homo Irrealis.