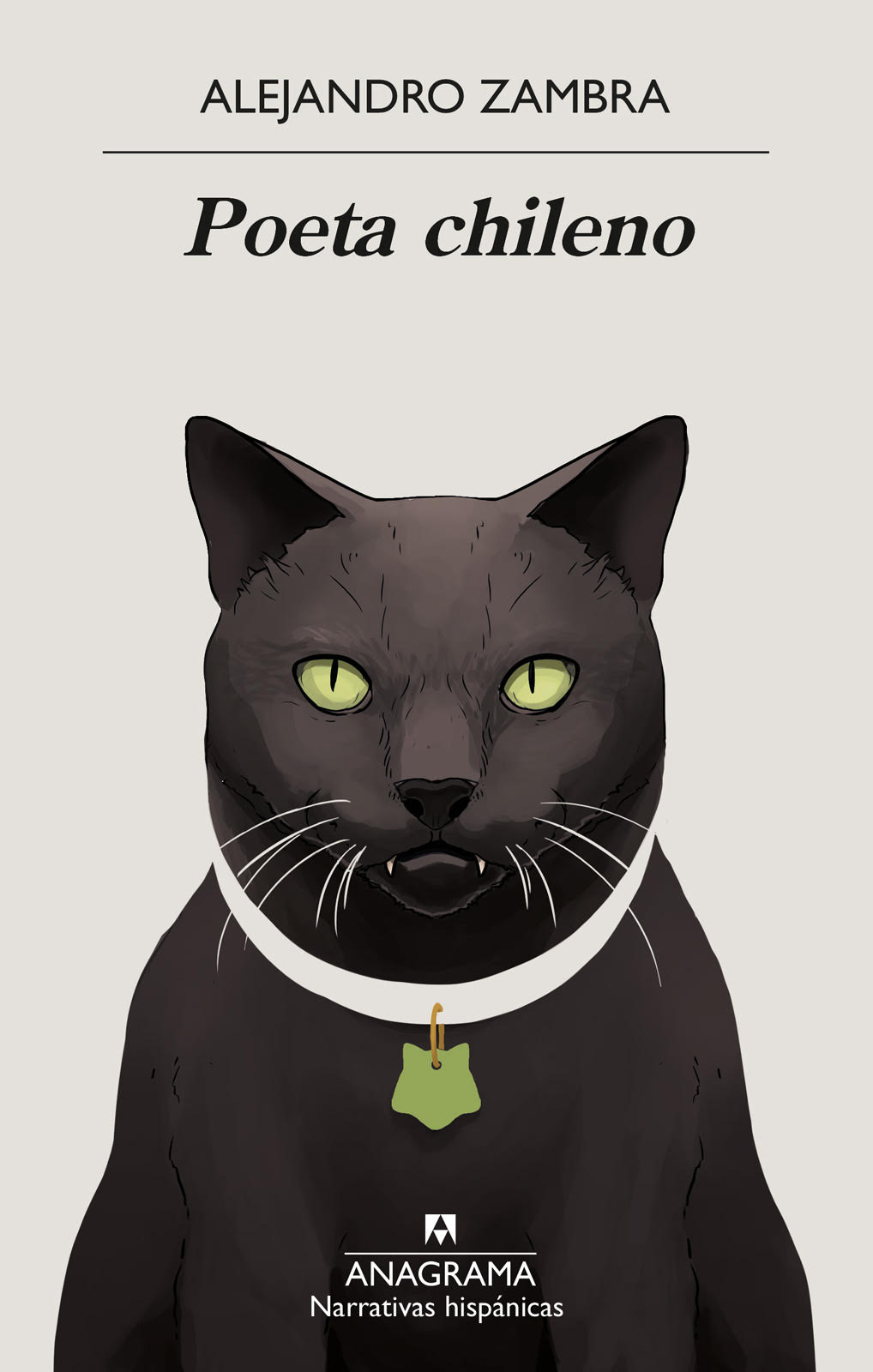

| Title | : | Poeta chileno |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 8433998935 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9788433998934 |

| Language | : | Spanish; Castilian |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 421 |

| Publication | : | First published March 1, 2020 |

Poeta chileno Reviews

-

Cálido y entretenido. Un libro compañero, como bien lo describe mi librero favorito. Y me encanta que sea tan chilenísimo con la chucha, que buena manera de acercar la poesía a una novela. Sin duda es una protagonista genial, te deja con ganas de leer toda la poesía chilena y más. Y tiene una fiesta de poetas que es muy divertida. Gran libro, muy recomendado.

-

Voy a comenzar el comentario a esta novela que con tanto humor ha escrito Zambra —empezando por ese Chile tan abundantemente poblado de poetas como quiltros recorren las calles de todas sus ciudades y pueblos— con una de esas confesiones tan al estilo de los homófobos o los racistas, algo así como que no tengo nada en contra de los poetas, de hecho tengo un amigo poeta, pero, uuuuffff, no soporto la poesía, o no la entiendo o me aburre o todo a la vez. No me juzguen, al menos no soy como la zorra que desprecia las uvas que no puede alcanzar, algo que parece que no pueden decir los poetas chilenos protagonistas de este relato que tanto desprecian a la novela y a los novelistas.

“Supongo que para escribir una novela hay que estar mucho rato sentado, no sé si aguantaría”

Una curiosa humorada porque es desde la novela que Zambra, también poeta, homenajea a los poetas, una novela que en su parte principal se cuentan las vidas de unas personas muy normalitas, desde sus primeros calores adolescentes, sus amores, la convivencia, los hijos que llegan y los que no, propios o ajenos, el profundo amor que se les tiene, la responsabilidad que con ellos se contrae, el inicio de las dudas sobre el amor que dan, sobre el amor que reciben, hasta los nuevos caminos que aparecen o se desea recorrer, las despedidas, los abandonos, los rechazos, en fin, nada muy llamativo, nada especial —“el registro casual de la vida cotidiana” —, y todo contado, como en la propia novela se dice, con “un tono ligero, contundente, inesperadamente personal… como alguien que piensa en voz alta”. Vamos, como dando la razón a los poetas en su desapego de la forma narrativa en la que alrededor de unas pocas páginas realmente literarias se acumulan grandes montones de paja.“Eso pensaba Pound… En una carta a William Carlos Williams dice qué él solo escribe las partes buenas de las novelas. Y que todo lo demás, las cuatrocientas páginas restantes, son puro relleno y aburrimiento”

Pues yo tengo que decir que he disfrutado de cada brizna de paja de esta novela. ¿Por qué? Ni la menor idea. Solo puedo decir que ha sido como volver a leer a Bolaño, algo misterioso que no se puede explicar pero que te engancha, aunque muchas veces me quede perplejo ante el sentido que puedan tener todas esas páginas y páginas de anécdotas o escenas que no sé muy bien cómo encajar en la novela ni encontrar un para qué satisfactorio.

Como Bolaño, Zambra nos transmite con una inmensa ternura repleta de humor y hasta de una mala leche cómplice todo el cariño que le despiertan sus personajes en particular y los poetas en general, su forma de ser y de existir, como si fueran palafitos, esas casas con patas que pueden cambiar de terreno sin modificar su identidad, sin ni siquiera tener que vaciar los cajones, quizás nada más que descolgar algún cuadro que se pudiera caer, pero que necesitan clavarse bien en la tierra para volver a su ser. Da igual que tengan tendencia a mirar las tetas de su bella entrevistadora, lo que hacen tanto ellos como ellas, da igual su problema de halitosis, da igual la cantidad de huevás en las que creen, el caso es que:“Es un mundo mejor … más genuino. Menos fome. Menos triste… creen en el talento, tal vez creen demasiado en el talento. En la comunidad. No sé, son más libres, menos cuicos. Se mezclan más…menos falsos que la vida corriente de quienes aceptan las reglas y bajan la cabeza. Por supuesto que hay oportunismo y violencia, pero también verdadera pasión y heroísmo y fidelidad a los sueños.”

En la novela se llega a decir que si escribiste un libro de Poesía ya eres poeta para siempre, “estás cagado”, pero yo creo que hay muchísimos más poetas que no han publicado nunca ni han llegado a planteárselo, y aun así son pocos, siempre serán pocos, hasta en Chile, bicampeona mundial de poesía, lo son. -

Irrepressible desires of youth are a driving force of poetry…

She loved music, she’d been an amateur photographer ever since she was little, and she was always reading some novel or other, but she thought poetry was childish and overblown. Gonzalo, however, like almost everyone, associated poetry with love. He had not won Carla over with poems, but he had fallen in love with her and with poetry almost simultaneously, and it was hard for him to separate them.

Soon enough Carla discards Gonzalo and from his suffering, his first poems are born…

However, poets are also obliged to live their ordinary, unpoetic lives…

Nine years elapsed and when Gonzalo accidentally again meets Carla, who by now has become a single mother, they start living together… Gonzalo happily raises his stepson and continues to write poems…He thought they weren’t bad, or rather that it would be hard to decide if they were good or bad, which meant they were more good than bad. He also thought they weren’t bad, but they were unnecessary. It didn’t seem like the world needed those poems. He wanted to write the poems no one had written before, but at that moment he thought no one had written these particular poems because they weren’t worth writing.

But one fine day Gonzalo wins a government grant to finance a doctorate in New York so he is compelled to exit the stage…

Six years went by… And although different water flows in the river now, history’s repeating… The eighteen-year-old stepson goes into poetry…Vicente read a couple more poems by Jorge Teillier, which Carla also liked, though she was distracted by the thought that poetry was like an illness her son had contracted, an illness associated with the little room, an illness that of course she preferred to his previous illness of sadness, but one that in any case worried her.

Poetry is atavism… Poetry is magnetic… Poetry entices… Poetry persists…

Then Gonzalo enters the stage once again…I am younger than my father

I am older than my son

And over my chest a shirt

is washed clean in the rain.

Poetic thought moves in unpredictable ways. -

Acabo de terminar esta novela y me siento como si me hubiese despedido de alguien importante en mi vida. «Poeta chileno» es un libro para amantes de los libros: porque en él transcurre la vida, que no deja de ser la mayor de las novelas; y porque, al final, la vida solo merece la pena cuando está rodeada de libros, y los libros solo merecen la pena cuando están enraizados de vida.

«Poeta chileno» es la historia de dos hombres, un casi padre y un casi hijo, y de cómo sus juventudes están marcadas por el amor a la literatura y a la vida literaria. Pero también es un libro sobre la familia: la familia como ente que se estructura y que, a veces, se desestructura de forma tan fulminante que después ya no queda nada. Y sobre la cultura chilena, a la que esta novela rinde un homenaje cariñoso y reverencial pero también irónico y satírico. Las vidas pequeñas, los gestos sutiles, las palabras olvidadas, el egoísmo, el narcisismo… y el amor por la belleza son elementos que salpican una novela hermosa, de una sencillez retorcida que pone al lector frente al espejo de su vida y de su entorno.

Recomiendo este libro muy encarecidamente. Es lo mejor que he leído desde «Nuestra parte de noche», se convierte en el primer libro del año que (sin duda) estará entre mis lecturas favoritas de 2022. ¡No os lo perdáis! -

Yo creo que, en sus novelas, Zambra siempre ha contado la misma historia: la de dos jóvenes enamorados que tarde o temprano atraviesan dificultades para encontrarse. Este libro no es la excepción, trata sobre eso mismo, pero en esta ocasión la historia se cuenta a través de una gracia contagiosa, fluida en su sintaxis y bastante alejada del punto seguido que siempre ha ceñido la escritura de Zambra. El relato sigue siendo el mismo, incluso hereda la melancolía citadina de sus textos anteriores, pero esta vez en forma de nostalgia pop que, a ratos, sobre todo en las dos primeras partes, pareciera funcionar como el guion de una sitcom de los noventa. Esto último hace que el relato sea consumible, ingenioso y entretenido.

Me gustó que Zambra incursionara en extensiones más vastas y articulara este relato como una novela de formación. El ritmo es increíble y apasionado y los personajes parecen ser un homenaje al connotado universo bolañesco de los poetas jóvenes. Gran, gran novela, está bien escrita y se lee muy rápido. ¿Qué mejor? -

Chilean Poet is Megan McDowell's engaging translation of Alejandro Zambra's Poeta Chileno, a serviceable story about family relationships, focusing on a stepfather and stepson. The book is fine, as far as these types of books go, although a bit milquetoast for my taste. The pacing is good and the characters likable, so I can see this appealing to a broad audience. The effusive reviews for the work in its original Spanish seem to bear that out. At its heart, this is an exploration of a certain type of (straight) masculinity in a world where traditional nuclear families are no longer given yet heteronormativity is assumed. I wasn’t put off by this, just found it limited. The satirical strands were humorous enough but the satire, like everything else about the book, was unremarkable.

-

Esperaba algo muy bueno y era muy muy muy bueno... Primera vez que leo un libro de 420 páginas en dos días. Muy recomendado.

-

Este libro me pego más fuerte que el coronavirus <3

-

Bolano has compared the Chilean poetry to his first dog: “When I was lonely he was like father, mother, teacher and brother all in one.” And this novel by a Chilean poet about the Chilean poets echoes this warm sentiment. Quite a few pages of this book is devoted not simply to the poets, but to the quirky, inspirational subculture of their community in Chile. Moreover, what is poetry for? It seems this novel attempts to discuss this question once again. In many cases it is impossible to say but there are “poems that prove poetry is good for something, that words can wound, throb, cure, console, resonate, remain”.

But even if you do not like novels about writers or poets, it is difficult to resist the charm of this particular one. Poetry is just a background for the relationship between a boy and his stepfather. Parenthood is obvious theme of a myriad works of fiction. But I do not remember reading any novel before about this particular angle. At least nothing of a kind which made me contemplate the uniqueness of this bond and its fragility. After the breakup with his girlfriend, Gonzalo had to leave his stepson after 6 years being practically his father. The mother does not want Gonzalo being involved in the boy’s further life. And when a biological parent would have some rights, Gonzalo does not have any. He has to leave. And it is such a sad situation that it would risk to become melodramatic in other hands. But Zambra treats it with such poignancy, self-deprecation and lightness that it never does.

I do not know why but I was thinking about Telemachus and disappeared Odysseus while finished reading. There is no obvious reference to this in the novel, just a feeling how the boy subconsciously absorbs some of his father’s personality in his absence. No any biological bond in this case.

The novel is not perfect. The third part that talks about the community of poets is only loosely connected with the main story. I wondered whether he could do better job either by more tightly Integrating it into the main plot; or by not trying at all and leaving it as a stand-alone story within the novel. However, I was happy he has included this part. I’ve found out so many interesting facts about the poets in Chile. At the centre of the part is American journalist, Pru writing an article:

“an article about a literary country, a country where poetry is oddly, irrationally important.” She interviews many writers for her mosaic of unacknowledged poets, or poetic types: “poet-critics,��� “poet-editors,” “poet-booksellers,” “poet professors, poet-journalists, poet-fiction-writers, poet-translators,” “several bards dedicated to less literary professions,” and one “poet-performer” who writes two poems, simultaneously, on separate sheets of paper with both hands. “The world of Chilean poets is a little stupid,” Pru concludes, “but it’s still more genuine, less false than the ordinary lives of people who follow the rules and keep their heads down.”

If the poets could at least a bit decrease the level of superficiality and falsehood in the world, I wish all of us would poets, at least a bit. Needles to say there were quite a few poems included in the novel. Some of them I really loved like this one by Enrique Lihn:

Nothing to lose by living, try it:

here’s body just your size.

We made it in the dark our of love for. The art of the flesh

But also in earnest,

thinking of your visit as a new game, joyful and painful;

out of love of life, out of fear of death and of life,

out of love of death

for you or for no-one.

I think anyone who hold a baby in their hands at least once could not help but be moved by those lines.

The language of the novel is pretty simple. And it is great as it is more immediate, not overburdened. Also it makes the digressions about the language stand out within. And there are quite a few of such discussions, for example about the connotations of the word “stepfather” in different languages. I also liked the appearance of the author. He did not overplay the trick. He has appeared only twice it seems. Both times I think he made a significant impact on the whole and moved the narrative away from a potential cliche.

And the ending was so smart and poignant at the same time that I was almost moved to tears simultaneously forgetting all my reservations about prior pages.

PS

I've forgotten to mention a brilliant translation by Megan McDowell especially considering the amount of difficult poetry involved. -

Puff!

Esta novela me hizo como quiso. Disfruté plenamente el desarrollo de la historia, me encariñé con sus personajes, me quedé con frases memorables y lo mejor de todo… comprendí mejor lo que es ser un poeta.

Chile y la poesía se vuelven un personaje más de este libro, que sin duda entra en los mejores que he leído este 2022.

Sublime escritura, cadencia perfecta y emociones bien descritas.

Ámonos, necesito leer más de este autor. -

diosmíodemivida

-

When my copy of Chilean Poet arrived, I snapped a photo and texted it to Mike Puma’s (GR friends from years back will know) old number like I would have done. We always raced each other to get and read books and Zambra was a favorite for both of us. Whoever has the phone number now texted back a bunch of question marks and I replied “you’re gonna have to deal with this.” I really miss my friend, but I’m glad Im going to be reading our author for him and haunting his old number on his behalf. Hopefully they pick up a copy of this too.

-

No se dejen engañar por el título insoportable que lleva esta novela, porque en verdad es muy buena.

A grandes rasgos, la historia se trata sobre dos hombres - padrastro e hijastro - y su relación con la literatura. Es más que eso, por supuesto: un estudio de la masculinidad, la familia y los afectos.

También es un homenaje a la escena literaria chilena. A sus personajes, sus lugares y sus costumbres. Leer esta novela es sentarse una vez más en los pastos de cualquier Facultad de Humanidades a tomar una cerveza comprada a vaquita. O, por lo menos, es como uno quiere recordar que fue esa experiencia.

Además es, en varios niveles, un cahuín. Se siente que el narrador te cuenta estos eventos, pincelándonos de sus intereses e inquietudes, con toda su pasión, como si fuese la historia más importante que ha contado. Se nota muchísimo el cariño del autor por cada quien - ficticio o no - participa en este relato.

Incluso es una reflexión sobre el oficio de la escritura. Una confesión a veces, un manifiesto a ratos. Encontré mucho consuelo en la pasión de estos personajes. En su vocación de escritores - o de poetas, más bien. En un sentido personal, me hizo muy bien leer esta novela. Creo que destapó algo en mi interior. Espero volverme más insufrible que nunca. -

Tourism sites frequently refer to Chile as the land of poets, although the only actual poet they tend to mention’s Neruda. Alejandro Zambra’s novel builds on this association between Chile and poetry, a country in which poetry’s a heroic practice, central to its mythology and a rich source of national pride. His book features two poets Gonzalo, who grew up during the dictatorship, and his stepson Vicente. In the early years of Chile’s democracy in the 1990s, teenager Gonzalo who, like Zambra, hails from Maipu has an intense relationship with Carla, after a few break-ups and some disastrous sex they finally part. Inspired by his feelings for Carla, Gonzalo now writes not-so-great poetry but that work has become crucial to his sense of self and his hopes for the future. Time passes, Carla and Gonzalo rekindle their relationship but Carla now has a son Vicente, and Gonzalo has to learn to how to be a parent as well as a partner. But his alternative family falls apart, Gonzalo leaves for New York and Zambra flashes forward to 2013 and Vicente’s life at 18, now an aspiring poet too, also inspired by his girlfriend leaving him.

Zambra’s exploration of parenting and the relationship between different generations of male writers seems to be a way of representing two versions of Chile itself. Both Vicente and Gonzalo attempt to craft their lives through crafting poetry. For Gonzalo, poetry’s essentially a solitary practice, predominantly masculine, romanticised, apolitical and individualistic, characteristics that make sense in the context of a person who grew up in authoritarian times. His attempts at parenting are similarly individualistic, there’s no sense of working with Carla as a partner in building their family. And, despite voicing regrets, he's easily able to abandon this family when other opportunities arise. For Vicente poetry’s more complex, rooted in community, passion, dissent and discussion, something that encompasses and embraces diverse voices. Although he’s also part of, what Zambra calls, a “generation of medicated children,” a comment on the consequences of being parented by adults shaped by traumatic historical events.

Zambra wrote Chilean Poet during recent political shifts in Chile, including the rise of Gabriel Boric to President. Boric’s earlier role as a radical, left-wing, student leader’s briefly alluded to here via Vicente’s engagement with the student protest movement. Zambra’s discussed Boric and his peers in terms of their potential for rewriting Chile’s past, overcoming trauma and opening up a space that allows Chileans to finally move forward. That hope for renewal and reconciliation emerges through Vicente’s character arc, underlined by the nature of his chance encounter with Gonzalo who’s finally returned to Chile.

This is an intriguing take on contemporary Chile but as a novel it sometimes felt closer to an academic exercise than a fully-realised narrative. It’s written in a detached, self-consciously ironic style; despite the interrupted timelines and abrupt shifts between the main characters’ perspectives the structure’s fairly straightforward, although there are occasional metafictional flashes. But as a story it’s slightly unbalanced, part of the plot’s unexpectedly dominated by Pru, an American journalist who meets Vicente while she’s on holiday in Santiago. At Vicente’s urging, Pru sets up a series of interviews with a cross-section of Chilean poets in order to document the Chilean literary scene. As a character, I found Pru less than convincing, she often felt more like a vehicle for a potted history of Chilean poetry, and her backstory including her identity as a lesbian, seemed a tacked-on, unnecessary digression, although Zambra’s nods to queer communities had a definite tokenistic feel throughout.

My overwhelming impression of the novel is that it’s rooted in an exploration of heterosexual masculinity, that’s particularly overt in Gonzalo’s episodes, and key to his identity – and presumably on some level Zambra’s, since Gonzalo often seems to operate as the author’s stand-in. Zambra is attempting a critique of his generation of men but doesn’t always communicate it that effectively. It may be this intense emphasis on straight masculinity, and its less-than-subtle handling, that has contributed to some reviewers’ sense that aspects of the text skew towards the homophobic. Pru is, however, quite an effective means of satirising the ways in which Chilean culture has been stereotyped by outsiders– the only Chilean writers Pru’s heard of are Neruda and Bolano. She also signals a possible shift from Chile as a place dominated by the output of other cultures – in Gonzalo’s Santiago the city’s soundtrack is almost exclusively American - to one that’s more invested in cultivating its own cultural landscape. I found a lot to engage me here, I enjoyed the moments of unexpected dry humour, and the inclusion of near-surreal scenes mostly involving Vicente’s cat. But I was uncertain about the portrayal of various figures and I also thought a number of sections - Pru’s descriptions of her interviews with Chilean poets, real and imagined for instance - had a laundry-list quality, while others felt unnecessarily stretched out, overly detailed, and awkwardly referential. So, overall, although I thought the central themes were worth exploring, this wasn’t always an entirely satisfying experience. Translated here by Megan McDowell.

Thanks to Netgalley and publisher Granta Publications for an ARC -

"Fue así como, mucho antes de aficionarse a la poesía y convertirse en un lector voraz, Vicente se volvió un acumulador de libros. Apenas tenía algo de plata iba al Persa Bío-Bío y compraba libros como si fueran manzanas o sandías, aunque la comparación no es buena...".

Realmente no sé como abordar esta reseña porque es una novela tan personal, tan deslumbrante y tan llena de libros, que me ha dejado muy sorprendida. No conocía a Alejandro Zambra y llegué hasta esta novela por la recomendación de un amigo, y en cuanto me puse con ella la verdad es que ya no pude parar. Es una novela que tiene vida propia, fluye casi por si misma como si llevara al lector de la mano corriendo casi sin respiro hasta el final de sus páginas. Lo que más me ha deslumbrado quizás haya sido toda esa amalgama de temas que trata casi sin darte cuenta.

Por una parte el concepto de familia del que habla Zambra, especialmente desde el punto de vista de la paternidad, y ya aquí me fascinó porque estamos tan acostumbrados a que sea la maternidad la madre del cordero, el centro del universo, que la reflexión que hace Zambra en torno a un padre que se siente padre por los cuatro costados solo por haber sido padrastro de un niño por unos pocos años, me llegó al alma.

"Pero hay que usar las palabras. Aunque no nos gusten. La palabra padrastro suena fea, pero es la palabra que tenemos. Hay otras lenguas donde la palabra es más bonita".

Y por otra parte el tema de la poesía, la literatura en definitiva, del que rebosa esta novela por todos los poros. Continuamente se esta hablando de libros, de autores, de poetas, qué maravilla porque te dan ganas de leerte todas las referencias (incluida La Montaña Mágica, una novela que siempre me dió miedo)

"Aunque todas las bibliotecas personales, como todas las personas, miradas de cerca resultan muy extrañas, esa primera versión de la biblioteca de Vicente era especialmente desconcertante porque junto a Millán y Dickinson comparecían novelas de fantasía como Luces Del Norte o El Catalejo Lacado o Un Mago de Terramar (...) Salman Rushdie, Agatha Christie y Lawrence Durrell..."

La novela está dividida en cuatro partes, que marcan las diferentes etapas en la vida de sus personajes: Obra temprana, donde conocemos a los adolescentes Gonzalo, aspirante a poeta, y Carla, y sus primeros escarceos en el amor;Familiastra, donde Gonzalo ya adulto se reencuentra con Carla y se van a vivir juntos, es en esta etapa donde conoce al hijo de seis años de Carla, Vicente y se convierte en su padrastro; Poetry in Motion, seguimos las andanzas de Vicente que con 18 años empieza a obsesionarse por la poesía y los libros, y finalmente Parque del Recuerdo una última parte que es una maravilla por todo lo que transmite y que no voy a resumir para no spoilear.

"¿Y hay alguien en Valparaiso que no sea poeta?"

Alejandro Zambra construye una novela divertida, fresca, con un ritmo que es un prodigio a la hora de ensamblar una historia tras otra, sin que la atención del lector decaíga por ningún momento. Es quizás una de las novelas que más he disfrutado este año, una absoluta maravilla por todo lo que transmite en su amor por la literatura, por la poesía, y por los libros como obsesión.

"Ninguna palabra española terminada con el sufijo astro significaba o podía significar más que desprecio o ilegitimidad. El calamitoso sufijo astro -forma sustantivos con significado despectivo- decía la RAE: musicastro, politicastro. La misma fuente definía la palabra poetastro como -mal poeta-.

-¿A qué se dedica tu padrastro?

-Mi padrastro es un poetastro -imaginó a Vicente respondiendo a eso."

https://kansasbooks.blogspot.com/2020... -

Do you have to like poetry to like a book called Chilean Poet? Just a little, perhaps. I love poetry and I loved this novel. I simply couldn’t put it down. Now it's finished I feel like I’m in mourning. Today I think I'll put on some black socks, forgo eating for a while and walk the city streets until dawn. But first, this review.

I should have been a Chilean poet. Instead of going to bed at a sensible hour most nights I should be getting involved in bar brawls instigated by random poets yelling “your poetry is shit!” at one another. Then shirtless and holding a raw steak to my eye I should be drinking pisco with the perpetrator of my ego-wounds while discussing with him the merits of a Gabriela Mistral sonnet. I should be reading and rereading the Chilean poets until their words are engraved on my flaming tongue. I should be penniless yet proud because a poem of mine got into one of the good anthologies. I should be forty-five and still called a young poet. I should be a hundred and four and still writing poetry. I should be stepfather to a budding young Chilean poet (¿quién más?). I should take the role seriously and be worried the word padrastro sounds too ugly but honour it nevertheless because it’s the only word in the Spanish dictionary to describe a man's relationship with his girlfriend's son (goddamn Spanish Academy) and by resigning myself to its use and being a good stepfather maybe the word’s connotation will change over time and I’ll have contributed in my own tiny way to making an ugly word beautiful.

Are poets people who devote their lives to making ugly words beautiful? The hell if I know. But one thing is clear: Chile is a country where poetry is more important than football, and, me, I was born in the wrong country. -

4.25.

Esto es un NOVELÓN. Muy recomendable, aunque no haya sido mi caso, para salir de un bloqueo lector, se lee como un libro de 200 páginas aunque tenga 400. Es ligero sin ser superficial y supura una sensibilidad y una humildad que lo convierte en una lectura difícil de olvidar. Sin duda leeré más libros de Alejandro Zambra. -

Zambra me ha gustado mucho más en otros libros. Para mí este tiene muchos altibajos, partes buenas y otras no tanto. La historia es débil, con demasiados enredos y algo previsible, y no me suscitó demasiado interés. Me gusta el recurso estilístico que es la intertextualidad, pero la mayoría de las referencias son hacia poetas chilenos que desconocía y son tantos que ni siquiera me dieron ganas de buscarlos. Tiene demasiadas referencias chilenas que para un lector de otro país como yo, me sacaban de la historia.

En varios pasajes las frases rozaban lo cursi. La poesía que escriben dos de los personajes principales es altamente olvidable. En fin, un libro que me generó gusto y rechazo. -

Así como Zambra dice, ojala hubiesen sido 1000 páginas llenas de dialogo entre sus dos personajes del final de la novela.

Que hermoso libro. -

¡¡La sensación de no querer irse nunca del bar y para eso pedir otra ronda de cerveza!!

(Maravilloso, simplemente maravilloso, acabo de terminarlo y ya quiero leerlo otra vez). -

No he podido resistirme a empezar a leer Poeta Chileno (2020), de Alejandro Zambra (1975-), después de la buena impresión que me causó su colección de relatos

Mis documentos (2013).

El título no puede ser más explícito. Estamos ante una novela por un lado claramente “chilena”, colmada de vocabulario autóctono, de referencias culturales y populares y que rinde homenaje a sus pueblos y a sus costumbres, y, por otro, repleta de poetas de toda clase y condición. La poesía se convierte así en la columna que sostiene toda la novela y el autor logra convencernos de su gran importancia dentro de la vida chilena (Baste recordar a Bolaño).

Alejandro Zambra nos cuenta la vida de una pareja no convencional, sus escarceos de juventud, sus encuentros y sus desencuentros. Ella, Carla, guapa, vital, inconformista; él, Gonzalo, menos agraciado, soñador y eterno aspirante a poeta. La historia continúa hasta la juventud del hijo de ella que también se convierte en protagonista de la historia. Los afectos y desafectos entre los tres nos llevan a plantearnos algunas preguntas: ¿Qué significa ser una familia? ¿Dónde reside la verdadera paternidad? ¿Debemos renunciar a nuestros deseos por los seres queridos?

En cualquier caso, parece claro que pesa más la primera palabra del título que la segunda, porque incluso en las partes más narrativas todo gira alrededor de la poesía. Todo en Poeta chileno es literatura, narradores, poetas y lectores.

Zambra escribe bien, sin digresiones, ni circunloquios, con precisas descripciones, toques de humor y un tono optimista adecuado al homenaje que en mi opinión el autor pretende. Sin embargo, el exceso de intertextualidad, con inacabables menciones a poetas y obras para mí desconocidos, y el constante debate sobre literatura me ha provocado, especialmente en la tercera parte, cierto cansancio y cierta falta de emoción y naturalidad.

En cualquier caso, una obra fácil de apreciar por todos los enamorados de la literatura en general. -

Her mo sa

-

Δεν ξέρω αν αυτό το βιβλίο είναι ένα βιβλίο για την τέχνη της ποίησης. Εγώ διάβασα μία σύγχρονη, πανέξυπνη, αστεία και βαθιά ανθρώπινη ιστορία μιας οικογένειας, διάβασα για δεσμούς άλυτους που δεν τους φτιάχνει το αίμα αλλά η αγάπη, διάβασα τον πιο σπαρακτικό χωρισμό και την πιο όμορφη επανένωση, διάβασα ένα βιβλίο από έναν άνθρωπο που αποτίει φόρο τιμής στη λογοτεχνία της χώρας του με πλήρη αυτοσυνείδηση της θέσης του μέσα σε αυτήν, ένα βιβλίο από έναν άνθρωπο που δεν φοβάται και δεν ντρέπεται να κάνει χιούμορ και που φτιάχνει ήρωες οι οποίοι, σαν σωστοί μιλλενιαλς (πάνω κάτω), έχουν οι ίδιοι χιούμορ και το χρησιμοποιούν σαν άμυνα κατά πάντων, διάβασα μια υπέροχη, διασκεδαστική και συγκινητική ιστορία.

-

“...He stands there paging through books that he has read before and that once astonished him.

“That’s almost all he remembers now, just that he liked these books, that once upon a time they fascinated him. Maybe it’s strange, but that’s how he is with novels, and with fiction in general: he tends to remember isolated phrases and words, specific scenes that his memory distorts, and above all atmospheres, so that if he had to talk about those books he would sound as tentative and unsure as if he were describing a dream. Plus, he used to read quickly, not trying to memorize anything, not even taking notes or underlining – at most he’d fold the corner of a page to indicate passages that were particularly significant or beautiful, but he didn’t even do that all the time, because books were sacred to him, even bad books were sacred. Now he respects them less, now he underlines them brazenly and fills them with notes and stick-on tabs, because reading is his job. Maybe he would playfully say just that, if someone were to ask: My job is to read.

“He does remember poems, though, because poetry is made to be memorized, repeated, relived, recalled, invoked.”

These words are Gonzalo’s, a Chilean who opens the book as teenaged protagonist, though really the protagonist is poetry. Or maybe atmosphere. Because even though I just put the book down, it is its atmosphere that won’t put me down.

It could be because Santiago, Chile, is the setting. It could be because I met a hundred poets, real or imagined. But it’s really because I’m almost sure, if I flew to South America, I could meet Gonzalo, now mid-life, and his lover Carla, and most especially his 18-year-old stepson Vicente who, like his father, might read novels but prefers to read poetry because, even though poetry books are thinner and might seem less substantial, they keep giving back and keep beckoning and keep valuing words so much more than prose, which passively entertains you and then, for the most part, leaves you.

Chilean Poet opens like a randy read, indeed, with Gonzalo a young Romeo finding a way to bed the beautiful Juliet-like Carla, but soon it settles into a young romantic novel with the modern angle of a lover serving as stepfather for a kid whose father is the typical deadbeat dad. And so a young lovers type story turns into a (step) father-son relationship type story depending heavily on quotidian events that are the lifeblood of such relationships.

The second half of the book finds Gonzalo estranged from Carla and gone to New York. Now we have Vincente about the same age as Gonzalo on page one, though more sensitive. Vincente, too, loves poetry. Vincente, too, tries to write it. And Vincente, too, has his “Carla” relationship, only with an older American journalist named Pru, who is writing a feature on Chilean poets, interviewing dozens of them.

The second half of the book has less structure than the Gonzalo-Carla opening act. It is, in fact, desultory. Vincente wanders, wonders, reads. Pru wanders, interviews, finds every known eccentricity among the Chilean poets who, in their interviews, speak so many truths about poetry and the people who read poetry and the many, many people who do not read poetry. Ultimately, a book that only seemed tangentially about poetry (the opening) begins to wrap itself around the universe of verse, thumbing its nose at narrative.

By then, though, you’re charmed. By then you are breathing the atmosphere and enjoying a slower and most un-American (read: U.S.A.) style of living. It feels good. It feels like you don’t want to fly back to New York anytime soon. And Gonzalo kindly returns to Chile to teach what he can’t write as a college professor, in doing so bumping into the stepson he hasn’t seen for years. Thus, the two narrative arcs intersect. And thus we return to the (step) father-son relationship that took the lead in the early going.

Meanwhile, like a book about reading, Gonzalo and Vincente, both alone and together, talk about books and poetry and even a few novels – cheap and forgettable (though in some cases lovely and friendly) as they are. Like G. and V., you might want to read these books, too. Two that met praise and I can recall now because I haven’t read either are Virginia Wolff’s To the Lighthouse and Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain. But it’s not always the fancy or obscure. Raymond Chandler even gets a lengthy shout-out.

Ultimately, like me, you might find yourself looking up all the Chilean poets mentioned here (and, sorry to say, Neruda is not good enough to complete your Chilean résumé – nice try). The trouble will be what the trouble always is with poetry. So many are out of print. So many are never translated. And so many, like Gonzalo's one obscure book, never appear in any bookstore anywhere.

Could I start reading this novel again, right now, even just after finishing it? Interestingly, I could, because unlike most novels it isn’t addicted to plot. Instead, it borrows atmosphere from poetry. And makes you want to walk the streets of Santiago or one of Chile’s seaside villages, walk into a cafe, have a drink and pastry or sandwich, and thumb through a book of poetry. Not one you will dog-ear or underline or sticky-note. One you will memorize, repeat, relive, recall, and invoke.

So I apologize if this review sounds tentative and unsure. That’s how it is with books like this. It’s like emerging from a dream, one where you want to roll over, fall back asleep, and continue living and breathing the Southern atmosphere, recapturing the magic that you can’t quite explain or defend should someone else come along and say, “Eh, it’s all right, maybe. Nothing great.” You know. One of those fiction readers who doesn’t like poetry. -

«Αν εκδώσεις ένα βιβλίο, είσαι ποιητής. Μπορεί να το μετανιώσεις αργότερα, αλλά άπαξ και εκδώσεις μία ποιητική συλλογή, είσαι ποιητής για πάντα, την έβαψες»

Αν γράψεις ένα ποίημα;

Αν γράψεις πολλά;

Πότε μπορείς να αυτοπροσδιορίζεσαι ως ποιητής, ως μουσικός, ως κ��λλιτέχνης, ως οτιδήποτε;

Πότε έχει δικαίωμα να λες «Είμαι ποιητής»;

Ο Γκονσάλο γράφει ποιήματα. Δεν του αρέσουν, αλλά όλη του η ψύχη είναι αφιερωμένη στην ποίηση και για αυτό ελπίζει πως μια μέρα θα γράψει κάτι που θα του αρέσει, που θα αρέσει. Και έτσι μαγικά θα νικήσει σε κάτι. Έτσι θα είναι αληθινός ποιητής.

Ταυτόχρονα, ελπίζει να γίνει αληθινός πατέρα για τον μικρό Βισέντε, και με αγωνία ψάχνει τη λέξη «πατριός» σε όλες τις γλώσσες, για να βρει από τις λέξεις απαντήσεις για ένα μικρό παιδί που ρωτά καμιά φορά και μία κοινωνία που ρωτά ασταμάτητα.

(*padrastro στα ισπανικά ενώ για στα μαπουντουνγκούν η λέξη για τον πατέρα και τον πατριό είναι μια, το ίδιο λειτούργημα)

Ο μικρός Βινσέτε, που ήταν εθισμένος στη γατοτροφή και αγαπούσε πιο πολύ από όλα τη γάτα του με την προβληματική οδοντοστοιχία, μεγαλώνει σε μια καμαρούλα με βιβλιοθήκη δανεική, με όσα βιβλία δεν πρόλαβε να πάρει μαζί του ο ποιητής πατριός. Και η αλήθεια είναι ότι δεν θυμάται και πολλά από όλα αυτά.

Δεν θυμάται όμως ξέρει πως είναι το ζενιθιακό φως στο ξεφλουδιμένο δέρμα, ξέρει πως είναι να θες να κοιτάς τη βροχή και να νιώθεις μια πληρότητα που θα την ζωγράφιζες μόνο σαν μια ευθεία γραμμή που δεν σταματά πουθενά. Ξέρει πως είναι η ψυχή σου να είναι ψυχή ποιητή, και αυτό να σε κάνει να βλέπεις μέσα τις λέξεις, πίσω από το φως και πιο βαθιά μέσα στην πραγματικότητα. Να νιώθεις παραπάνω, συνέχεια, και να μην ξέρεις τι να κάνεις για αυτό, και έτσι να βάζεις λέξεις στη σειρά και το σώμα σου να γίνεται χαρτί. Ξέρει πως οι λέξεις πονούν, σφύζουν, θεραπεύουν, παρηγορούν, αντηχούν, διαρκούν.

Το να είσαι Χιλιανός Ποιητής λοιπόν είναι σαν είσαι Βραζιλιάνος ποδοσφαιριστής. Και ο Βισέντε είναι ένας Χιλιανός ποιητής και ο Zambra είναι ένας Χιλιανός μυθιστορηματογράφος. Και οι Χιλιανοί μυθιστορηματογράφοι γράφουν μυθιστορήματα για τους Χιλιανούς ποιητές και έτσι προέκυψε το εν λόγω βιβλίο.

Ένα εξαιρετικό μυθιστόρημα για την ποίηση, για την ψυχοσύνθεση των ποιητών αλλά και του κόσμου που τους περιβάλλει (που δεν είναι σιγουρά ποιητικός, αλλά έτσι τον βιώνουν εκείνοι), για ολόκληρο το σύμπαν της ποίησης και του νεανικού έρωτα, με μάτια ποιητική, ευαίσθητη και ταυτόχρονα εντελώς ρεαλιστική.

Ένα βιβλίο που σε κάνει να κλαις αλλά και να γελάς και αν έπρεπε να διαλέξω τα 5 αγαπημένα μου βιβλία θα ήταν μέσα σε αυτά σίγουρα.

Το μόνο που με έκανε να το ξαναδιαβάζω μόλις το τελείωσα, σιγά σιγά, χωρίς αγωνία τώρα που ξέρω τι θα γίνει, και να ανακαλύπτω συνέχεια παραπάνω μαγεία! -

El que no sintió deseos irrefrenable de correr a escribir poesía después de leer esta novela no la leyó a conciencia.

-

Vijf sterren. Niet omdat het perfect is, maar omdat dit zo'n boek is waardoor je dat geluk voelt een bóék te lezen, het bij je te hebben als je de deur uit gaat en het overal open te kunnen slaan om die andere wereld in te tuimelen. En dat is lang niet altijd zo.

Het begint met de jonge geliefden Gonzalo en Carla, die onder een poncho bij haar moeder thuis op de bank zitten en nieuwsgierig first, second en third base verkennen. Maar het gaat uit en ze gaan allebei een eigen kant uit.

Een tijdsprong: zeven jaar later. Ze komen elkaar weer tegen in een discotheek. De aantrekkingskracht is meteen terug, ze hebben seks (zeker het eerste deel van dit boek bevat veel - goed beschreven - seks) en tijdens die vrijpartij denkt Gonzalo het al aan haar lichaam te zien: ze heeft een kind gebaard.

Dat kind is Vicente. In de jaren erna leven ze met z’n drieën. Gonzalo is zijn stiefvader en onderzoekt wat die rol, wat die term, voor hem betekent. Dat de jongen belangrijk voor hem is, is snel duidelijk. Gonzalo probeert ondertussen als dichter gepubliceerd te worden.

Maar het loopt niet zoals gepland, natuurlijk. En met de wendingen van die levens verschuift ook de focus van het verhaal. De stem van het boek blijft achter bij Vicente, die ook poëzie gaat schrijven, en, later, bij Pru, een journalist uit New York die door een misverstand in Santiago belandt en dan maar besluit een stuk te schrijven over Chileense dichters en de Chileense subcultuur waarin die zich bewegen.

Ook zij vertrekt op den duur weer, en dan neemt de schrijver met een mooie vormkeuze afscheid van haar. Ineens is er een ‘ik’, op pagina 350:En dan vraagt Pru zich af of ze niet in Chili zal blijven, maar haar leven is geen wonderbaarlijke B-film, dus ze stapt in het vliegtuig en het liefst zou ik met haar meegaan en haar overal naartoe volgen, net als het hondje Ben, maar op dit moment zijn er een miljoen romanschrijvers die over New York schrijven, waarschijnlijk onder het luisteren of neuriën van dat prachtige liedje dat luidt New York I love you/ but you're bringing me down en ik wil hun verfijnde romans, waar ik bijna altijd van hou, lezen, ik ga proberen ze allemaal te lezen om te zien of Pru ergens in voorkomt of iemand die op Pru lijkt - echt, ik zou heel graag met haar in het vliegtuig stappen, maar ik moet op Chileens grondgebied blijven, bij Vicente, want Vicente is een Chileense dichter en ik ben een Chileense romanschrijver en Chileense romanschrijvers schrijven romans over Chileense dichters.

Hier zit veel in over wat voor boek dit is. Een eigenzinnige vertelstem, een schrijver die zijn personages met veel warmte en genegenheid beschrijft, een handvol speelse vormkeuzes (die wat mij betreft niet allemaal even geslaagd zijn; soms is het te flauw). Het is misschien vaak wat te uitvoerig beschreven, maar tegelijkertijd is het rijk en met een mooie, melancholische toon. En het gaat dus, zeker in de tweede helft, ook veel over het wereldje van Chileense dichters. Maar vooral gaat het over onderwerpen die ons allemaal aangaan, liefde, seks, boeken, muziek en dat alles de hele tijd maar van voorbijgaande aard is. -

El libro más tierno de la historia. Sobre todo la primera parte, te hace sentir chiquito-chiquito todo el tiempo, te da ganas de reírte y de llorar a la vez. Es una gran novela, qué bien haberla leído.

-

Te quiero mucho, Alejandro Zambra.

-

Encuentro que acabo de leer uno de los mejores libros de mi vida. Pienso que es hermoso, que lo amo y que cualquier cosa que diga no hará dimensionar lo muy hermoso y precioso que es y lo mucho que vale la pena leerlo. Amo con mi vida las historias de amor y uffff, esta me dio mucho.