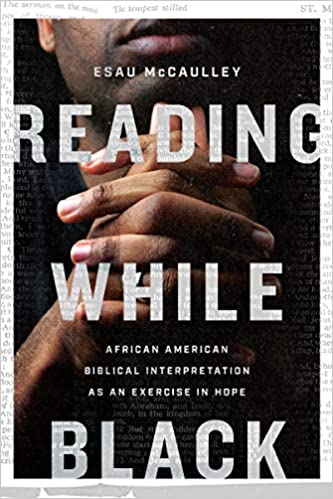

| Title | : | Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | - |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Kindle Edition |

| Number of Pages | : | 200 |

| Publication | : | First published September 1, 2020 |

| Awards | : | Goodreads Choice Award Nonfiction (2020) |

Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope Reviews

-

I didn't know what to expect going into this book. Was I part of the intended audience? Would it be more about political ideology than biblical reflection? Well, as evidenced by my five stars, I was thoroughly impressed. One need not agree with McCaulley’s every statement (I didn’t) to acknowledge and appreciate what he’s accomplished in this work. With biblical-theological skill he brings textual insights to bear that are often illuminating and moving.

Social location is not everything in reading our Bibles, of course, but it’s not nothing either. McCaulley showed me things in the text that, frankly, I’ve never had reason to notice. He is a remarkable writer who defies easy categorization—a conservative Anglican who, self-admittedly, can often feel like a cultural outsider among white evangelicals and a theological outsider among black progressives. (And just patronized by white progressives.)

Overall this book deepened by gratitude for the miracle of the black church, forged and sustained in the fires of suffering. The irrepressible courage and biblical fidelity which marks so much of black church history is a blazing testimony to God’s love for the downtrodden. (For more on this, see my brief review of Mary Beth Swetnam Mathews’s “Doctrine and Race: African American Evangelicals and Fundamentalism between the Wars.”) Above all, McCaulley’s book made me more amazed by the subversive beauty of Scripture—the searching Word of a liberating God. -

How does the Black American experience fit into the Bible? At first glance it may not seem like it does. American history has shown that the Bible has been used to promote slavery, segregation, and Black inferiority. To some Black Americans, reading the Bible may seem like an exercise in despair and subjugation. Dr. Esau McCaulley says a resounding NO, reading the Bible can be an exercise in hope, we just need to know how to read and interpret it correctly. McCaulley’s new book Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation As An Exercise in Hope covers how the Bible addresses topics such as policing, being a political witness, the Black identity, and slavery.

McCaulley begins his book by explaining that the Black church tradition is known for: advocating justice, affirming that Black people have worth, and promoting a “multi ethnic” body of believers. He spotlights how Black Christianity has always challenged White Slaveholder Christianity, from the days of slavery to our current moment. McCaulley states that American culture may deny dignity and hope to Black Christians, however they are able to find these two truths in the Bible.

This book is coming out at just the right time in our political moment when issues of policing and systemic racism are front and center. One chapter deals with policing and how it is addressed in the New Testament. McCaulley draws clear parallels between how Christians interacted with the Roman guards and how Black people interact with police today. He also writes about the importance of Black Christians being involved in politics by calling out injustices and the evil policies implemented by governments and leaders.

One of his strongest chapters (Chapter 5) deals with the Bible and Black identity. It was definitely written to respond to hoteps, even though McCaulley does not use that term. He challenges the assertion by Black Secularists that Blacks shouldn’t be Christian because they were only introduced to the religion because of slavery. McCaulley challenges that notion by highlighting African people who are mentioned in the Bible (specifically Simon the Cyrene and the Ethiopian Eunuch) as well as during the early history of the Church when the Gospel was introduced to Ethiopia and Nubia.

He closes his book by addressing the Bible and slavery, answering questions such as whether God intended for slavery to happen in America or was it a by-product of the Fall? He provides a fascinating argument about how Black Christians read those verses of the Bible that tended to condone slavery and provides a strong Biblical rationale for why American slavery was not ordained by God, however, freedom is and that is good news!

Reading While Black would be a great book to study in Black Churches for adults and teenagers. I personally wish this book had been around, or a young adult version of it, when I was a teenager. There were times, when I was in school, when I read about how the Bible was used to promote racism and I never knew how to reconcile the faith I was raised in with the one that promoted the oppression of my ancestors. McCaulley’s book teaches Black Christians how to do that work and also provides an excellent history on how Black religious leaders and scholars of the past interpreted the Bible to give them hope and freedom.

Thanks to NetGalley, IVP Academic, and Esau McCaulley for a free ARC copy in exchange for an honest review. This book will be released on September 1, 2020.

Review first published in Ballasts for the Mind:

https://medium.com/ballasts-for-the-m... -

Esau McCaulley is professor of New Testament at Wheaton College, an ordained Anglican priest, and a fellow board member of the Institute for Biblical Research. I'm guessing that he wrote Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope (IVP, 2020) with Black readers in mind. But this white girl found it both helpful and inspiring.

I used to think that making space at the table for people of color was a matter of equality or justice, and that's part of it. People of color are made in the image of God and they should get a chance to speak. In theory, I imagined that reading the Bible with people from other cultural backgrounds would also be enriching. But I had no idea what I was missing!

Over the past 5 years or so I've been reading more widely and adding books to my own library and to my college's as fast as I can. I'm convinced now that when we only listen to people who look like we do, we're missing out on a ton of insight. I'm discovering a rich world of biblical reflection by African, African-American, Latinx, Asian, Asian-American, First Nations, and Islander believers.

Reading While Black fills an important gap in my library as well as in my understanding. Ironically, much of what is published by minority authors reflects the politics of the ivory tower -- critical of Scripture -- at times representing a departure from the faith tradition. (There are probably a variety of reasons for this, but I suspect that university presses are simply well ahead of faith-based publishers in seeking out authors of color.) As a result, it's much harder to find published works that represent the views of the majority of churches in the global south, churches which are by-and-large conservative.

In Reading While Black, Esau seeks to recover the resources of the Black church tradition that arises from the pulpit and the pew rather than from the ivory tower. He models a faith-filled reading of the biblical text that remains engaged with politics and justice but does not neglect the call to holy living.

Each of his chapters tackles an issue about which the Scriptures have something profound to say -- a theology of policing, the political witness of the church, the pursuit of justice, black identity, black anger, and slavery. He issues a prophetic call back to the Scriptures and to a life of faithfulness. His is not a call to "make the best of" systemic injustice, nor does he seek a violent overthrow. Esau engages tough questions with verve, urging active but peaceful resistance to injustice.

Many are wondering what to do when the protests have ended. How can we keep listening? My official endorsement of the book reads:

How can the church today effectively address the racial tensions that plague our nation? Esau has convinced me that the Black Church tradition holds the key -- maintaining fidelity to the Scriptures while fully engaging in the struggle for justice. This book is an excellent starting point for those who want to listen and learn a new way forward. Esau's prophetic voice is rooted in Scripture and full of hope. Highly recommended! -

Hermeneutically dangerous. McCaulley may protest that he is not pushing Critical Race Theory, but this book gives the lie to that claim. His postmodern epistemology is evident throughout, and it will undermine orthodoxy. He rightly critiques racist theologians of the past, but fails to state clearly that their error was that they were objectively wrong about the Bible, not that they failed to include enough black voices – as though truth were a matter of combining all our biases and stirring them together. In the same way, McCaulley’s failure to condemn liberal theologians who deny the gospel but happen to share his skin color makes him a Trojan horse for evangelical Anglicanism. His promotion of irresponsible myths, such as the idea that Simon of Cyrene or Rufus and Alexander were black (they were almost certainly of typical Mediterranean or Roman African complexion) reveals ressentiment. This is the man who tweeted, “What does it mean that most of our English Bibles were translated with very few Black or other Christians of color or women involved?” – to which I reply, “It means that you have been blessed to receive the Bible from people who were not black” – not least, the Jewish males who wrote the Bible in the first place.

-

Excellent. The chapter surveying the biblical teaching on slavery is especially worth the read.

-

My goodness. Where do I begin? Reading While Black has given me the much-needed reminder of the necessity of listening to, learning from, and amplifying diverse voices in theological method. This is not a book that I will read once only to discard it to my bookshelf. No – this is a book that I will be reading and re-reading in the coming years.

Esau McCaulley is an ordained Anglican priest and a professor of New Testament at Wheaton College. In Reading While Black he explores the message of hope found in the Black ecclesial tradition. He does not seek to innovate, nor bring a fresh reading to various texts, but rather remind others of the home that is the Black ecclesial tradition. Writing with popular audiences in mind, he gives practical guidance for laypeople to gain a deeper engagement with the breadth of Scripture.

Reading While Black brings a joyous reminder of the powerful truth of the character of God. It offers clear, robust exegesis of texts that far too often have been colonized, offering a more holistic reading of passages such as Romans 13 and 1 Timothy 2.

Dr. McCaulley maintains an unwavering faithfulness to Scripture while calling the Church to a better understanding of policing, political engagement, Black anger, Black identity, and slavery.

This book has encouraged me to treasure God's self-revelation in Scripture, challenged me to listen and learn from the various traditions of the global Church, and reminded me of the hope that I have in the coming Kingdom. -

Esau McCaulley opens this book with the assertion that Black ecclesial interpretation “got somethin’ to say” about the Bible. By the end of the book, I totally agreed. McCaulley looks at a number of questions about the Black experience in the US, present and past—policing, politics, justice, identity, anger, and slavery—and asks what the Bible says to these situations. Some quick points that I will be contemplating for quite a while:

**The twelve tribes of Israel were never a racially or ethnically “pure” group. Jacob accepts Joseph’s two sons and so incorporates African blood into the family right from the start. God’s promise to reach all the world through Jacob’s family thus starts happening at the very beginning.

I loved McCaulley’s perspective on many parts of the Bible that I thought I knew pretty well. I still have a lot to learn, and the learning is a thrill. My only criticism of Reading While Black is that I wanted it to go more in-depth (only 184 pages??). But for now, I’ll be content with this book and eagerly await what McCaulley writes next.

**The Bible sometimes speaks from the standpoint of God’s creational intent—the way the world is meant to be—and other times speaks to what God allows because of human sinfulness. McCaulley points out how Jesus responds to the Pharisees’ questioning about divorce (Matthew 19) not by expounding upon Deuteronomy, as the Pharisees had intended, but by returning to Genesis, to God’s original intention for the world. In the same way, the Bible speaks to proper relations between masters and slaves, but that doesn’t mean God’s intention was that there be slavery; rather, those passages are making allowances for the way Roman society functioned, with the intention that slavery be eradicated.

**Through and through, the Bible takes seriously the rage of the oppressed against the oppressor. The Psalms give voice to that just anger, and the Hebrews are reminded that they (we) were all once slaves, having been rescued by God from Egypt. Slavery is our heritage as God’s people, and the anger and bitterness are real. But God’s purpose all along has been the redemption of all people through the family he chose—and in the New Testament we see the astounding quality of that promise when it means loving the oppressor and the enemy, even when they clearly don’t deserve it. But the Bible also balances this with the assertion that there will be a final reckoning. God’s justice doesn’t mean ignoring all the injustice of human society.

**Where the Bible seems to stop short of encouraging all-out rebellion against the evils of politics, government, and systemic injustice, it’s not overlooking those evils nor telling us to just put up with it. Rather, the lesson we learn is that God knows the right time and way to overthrow injustice, and he will do it; we will always want to revolt and try to rid the world of evil, and sometimes that’s the right thing and other times it’s not the time or method just yet. The Bible teaches us to want the right things and to wait for God’s timing. -

4.75 Stars — Wow. A riveting, gut-punch of a read, I just could NOT put this down, such was the ferocity & starkness of the content and especially the prose.

Best not to giveaway too much, but for me this is a life-awakening piece of literature that paints a vaguely familiar picture but does so with a completely customised and unique set of brushes. A topic so relevant yet so bereft of genuine published content, despite the recent vein of excellently written, poignant literature on race & the truth about white-privilege and the still reticent views of the white majority, that racism is ‘a thing of the past’....

Never before have I been so lost when it comes to cogitating the bible, as my perspective has been given a genuine and much required shake-up. -

Reading While Black takes a look at African American interpretations of the bible and how they differ from conventional interpretations from white churches in America. I would clarify that these interpretations are not so different that they diverge from biblical canon. Instead, it focuses on the idea that Christianity is about freeing the oppressed and unity for all races and ethnic backgrounds. There are many examples of this in the bible (ie. Moses leading the slaves to freedom, and the unification of Jews and Gentiles). He also points out that one of the places Christianity originated from is North Africa.

With that in mind, I really enjoyed reading about interpreting the bible through a different perspective. As an Asian American who grew up in white evangelical churches, it can be really isolating when biblical norms seems to tie into white culture. Over time, I've been trying to expand my knowledge on how the bible is interpreted by different groups of people. Reading about Black Christian culture and its biblical interpretations has been really enlightening and incredibly important. I find that it helps us develop a more holistic view of the bible that's not homogenous to an individual culture or perspective. Reading While Black is an important book that gives us a window into the Black Christian identity, and shows us that God's redemptive grace is for the oppressed, and standing against injustice is in fact a biblical thing to do. I encourage people from a traditional western Christian background to read this book in order to understand the bible from a different lens.

Thank you NetGalley for letting me read and review this book.

Visit my Instagram

@vanreads for more of my reviews. -

Full review:

https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/re...

To appreciate what Reading While Black offers, one needs to catch the basic contours of this ongoing conversation about God’s eternal Word and black people’s earthly concerns. McCaulley satisfyingly situates the discourse both for those who’ve been, and also for those who’ve just started, listening.

Broadly speaking, when it comes to this conversation some progressives, black and otherwise, have offered a hermeneutic of revision, believing the Bible will be good news to the black experience insofar as we revise it to be so. On the other side of the conversation, some evangelicals have unwittingly—and ignorantly—offered us a hermeneutic of irrelevance, suggesting the Bible says next to nothing about the black experience by virtue of anemic application for justice. Recounting his own wandering through both sides of the conversation, McCaulley urges us to refuse this binary. -

This book was spectacular on a multitude of different levels. I've always been fascinated to hear what people of different ethnicities and cultural backgrounds get out of reading Scripture - if we all come to the Bible with our own sets of presuppositions, then it makes sense that whatever tradition we grew up in has blind spots, that we have things to learn from other traditions than our own. In READING WHILE BLACK, New Testament professor Esau McCaulley sets out to encapsulate the specific emphases the orthodox Black American church of his upbringing takes from its reading of Scripture. The result is well worth reading.

There are so many good things in this book. I grew up in a politically conservative and white context where certain hard conversations simply were not had, and certain delicate questions were not asked. This book is the first place I've ever heard, for instance, a genuine discussion of what Psalm 137 is all about, including the raw bits. As I have tried to start having those conversations and asking those questions myself of more recent years, I've often bemoaned the paucity of examples by older, wiser siblings in Christ who have walked this path and asked these questions before me. Given this lack, McCaulley's book is a breath of fresh air - committed to orthodox Christianity, but not afraid to have those difficult conversations either.

This brings me to one of the main things I think this book (and by extension, the entire tradition of Black American Christianity) has to say to white Christians. So many of my friends seem to have had traumatic experiences in abusive families and churches, including a plentiful helping of spiritual abuse; now they are going through the painful process of questioning everything and battling to hear God's voice past the voices of those who have quoted Scripture to justify their abuse. But this is an experience the entire Black church in the US has lived its entire history. Black people have been targeted by unjust systems for hundreds of years, and all too often they've had Bible quoted at them to justify this abuse. In response to this systemic spiritual abuse, the Black church has developed an orthodox and profound theology of liberation. I feel like a guppy even pointing this out: it feels like it should have been so obvious. But, the Black church has been working through this for centuries. Maybe it's time we started learning from them.

Related, I've always had a strong interest in questions of justice and injustice and what the Bible has to say to them. As part of the broader Reformed church, I was constantly being taught from the pulpit to obey governing authorities without question unless they absolutely required me to sin, and reminded that my Christian life and witness should remain thoroughly internal, with nothing to say to broader matters of social justice. As the child of my parents, however, I was raised to question authorities, use my conscience, and expect my faith to have a transformative effect on the world around me. READING WHILE BLACK may actually be the very first time I have come across a spirited defence of the social and political ramifications of Christian faith, and an exegesis of Romans 13 that recognises the revolutionary nature of Paul's description of magistrates as the servants or ministers of God, that doesn't come from within my own very small fringe element of white Calvinists. McCaulley says many of the things Rushdoony and North (and McDurmon) have been saying for decades, with a slightly different perspective and emphasis, in a tradition which has, apparently, been saying all these things for centuries already - and with far, far higher stakes and far more skin in the game.

White Christians have so much to learn from the Black church in America - this book is a great place to start. While there were places where I wished McCaulley had gone a lot further (dare to dream the total abolition of police, my friend!) I hope it becomes very widely-read. -

Summary: A study of biblical interpretation in the traditional Black church that emphasizes the conversation between the biblical text and the Black experience and how this sustains hope in the face of despair.

Esau McCaulley describes his journey from southern roots to white evangelicalism and progressive scholarship and back to the Black church tradition. He recognized that both evangelical and progressive traditions didn’t offer the wherewithal to deal with the Black experience of slavery and racism and to sustain hope amid despair. McCaulley found this by going back to the Black church, both its biblically rooted resistance to slavery and injustice, and its message of hope of liberation, not merely spiritual but in terms of bodily status.

McCaulley offers this description of biblical interpretation how one reads the Bible while Black:

--unapologetically canonical and theological.

--socially located, in that it clearly arises out of the particular context of Black Americans.

--willing to listen to the ways in which the Scriptures themselves respond to and redirect Black issues and concerns.

--willing to exercise patience with the text trusting that a careful and sympathetic reading of the text brings a blessing.

--willing to listen to and enter into dialogue with Black and white critiques of the Bible in the hopes of achieving a better reading of the text.

The next six chapters address issues facing the black community and how the tradition of Black church reading of scripture addresses each. The issues are: policing, political witness, the pursuit of justice, Black identity, Black anger, and slavery. The treatments are not exhaustive but are meant to point toward the resources of biblical interpretation open to the Black community. The concluding chapter centers on hope, which is the outcome of engaging the biblical text and looking for answers to these pressing issues. A “bonus track” goes further into the ecclesial, or church-centered aspect of this approach to biblical interpretation.

I will not go through McCaulley’s discussion of the six issues but focus on the first as an example of the approach he commends. First he begins with context, and his own experience of being stopped by police while at a gas station, as he was driving friends to a party. He then turns to Romans 13:1-2, often weaponized against the Black community. He observes how we often look at the instructions for citizens without considering the powers subject to God, and why, in Paul’s context the recipients of his letter are subjected to an evil empire by God. What the passage raises is a form of theodicy. McCaulley reads this passage canonically, setting Rome alongside Pharaoh (cf. Romans 9:17) in which God is glorified through his judgment upon wicked kings. If Moses was not sinful in his resistance to Pharaoh, then submission to authorities does not preclude calling evil by its name. Furthermore, verses 3 and 4 of Romans 13 speak to the just use of authority, to reward good and punish evil, and not the reverse. Policing that treats citizens otherwise ought to be reformed. It should not engender fear in those who do right, no matter the color of their skin. McCaulley observes then that how Paul deals with the evil Roman empire is not to refer to their evil but to talk about how just rule is exercised in a way that assures rather than arouses fear in the lives of the governed who do what is right.

I look at this and ask the question of how often have I heard the text taught in this way in the white church? Yet the implications for how those with police powers ought exercise them, as well as the obligation of submission, are both in the text. Both Pharaoh and Rome are in Romans. Yet where has this connection been made that speaks of how God judges evil empires and glorifies himself? Those whose social location is in the Black church in America see these realities in the text more readily than many of us.

I cannot read while Black. I read from a social location that makes me more aware of some aspects of scripture while missing others. What I’ve come to recognize as I’ve grown older is how much I’ve been blind to in scripture. I can only understand the whole counsel of God with the whole church. While I cannot read while Black, I can read with the Black church, to listen to their readings, always searching the text to see if these things are so. And what I find in many instances is that they are, and I had not had eyes to see. Open my eyes, Lord!

____________________________

Disclosure of Material Connection: I received a complimentary review copy of this book from the publisher in exchange for an honest review. The opinions I have expressed are my own. -

This book is about black African-American views of Biblical interpretation, with a connection to history (slavery times onwards) and present struggles, “an exercise in hope”. A life between hope and despair. The Christian groups mentioned here are all Protestant, no mention of the Catholic, or even perhaps Orthodox ones, but all no doubt will find useful things here, and explanations/surprises and food for thought. And you’re not black but still curious, you will still find things here that you might not have thought before (and not just about the black experiences; for example how the Roman rule must have been felt by the parents of John the Baptist, who dealt with faith questions from the people they served as a priestly family, in their life.

The author is an Anglican priest, column writer, and an assistant professor. He has arranged each chapters subjects very well, with good conclusion for each chapter. The reading group discussion guide at the end might make each chapters subject even clearer (there’s also a scripture index). There are seven chapters, a conclusion, and a bonus chapter with more talk on the black exegetical tradition (incl. the importance of literacy, having your own churches, getting the chance to do academic study only from mid-20th c. onwards, on black women’s POV, and on patience not to go on rejection mode just because of one passage but to search more).

The author puts a little of his own experiences at the start on each chapter, then goes deep into Bible texts to talk about each subject (he does say that he made an effort not to be too thorough so as to make this book more readable to everyone; and this book is absolutely not too thick. Subjects include having a case for police reform, political witness of the church, on justice questions, identity, black anger and disappointment, and slavery. It is clear that what parts of the Bible white people have used against black people and slaves don’t stand on firm ground. There are plenty of parts in the Bible that could work against their twisting things to their own benefit, some of them subtle but easy to realise if you think about it, and look in more than just one place (fe. with Paul, when he talks to Philemon about Onesimus, or to Corinthians about purchasing your own freedom). The slaves quickly found plenty of hope and support in the Bible, even when they couldn’t (yet) read it (Exodus is a quite obvious one, and easy to find and read about).

Although this is not a thick book – and that’s good – there is much packed in there, without loading the pages too full. It is a good book for the people the author aimed this book to mainly write to, but even others who don’t always even live in America will find plenty to think about, things to realise, maybe even further reading demanding attention. A very good book on the subject of Black Biblical interpretation, where hope can be find in it, and no doubt, much needed non-white POV. -

Absolutely brilliant.

McCaulley presents here the hope and history of “black ecclesial interpretation.” This is the tradition of reading and preaching found in the black churches since the earliest days of America. One of the challenges McCaulley puts forth in the beginning is the pull from one side to leave the Bible and Christianity behind, seeing the whole religion as white European and not good at all for Black people. McCaulley argues in one chapter that there have been Africans in the people of God from the beginning (literally, Genesis) and throughout the early church. Christianity and the Bible belong to Black people.

Honestly, those of us who are white Christians need to take a step back from assuming we have the right answers to all elements of theology. McCaulley’s book ought to be must-reading for white pastors and teachers.

McCaulley talks about the way white Europeans set the tones for Biblical interpretation. This leads to liberals/modernists who deconstruct the Bible and fundamentalists who take it as is. McCaulley shows the Black church has never felt the need to go with this either/or. Nor has the Black church felt the need to separate salvation from liberation. The same God who saved souls also liberates slaves.

I think the best chapters in the book were the first couple where he discussed policing and government. In these chapters, McCaulley brought forth points and connections I had never made before. Well, to be honest, connections I had never made before when thinking about faith and politics in Romans 13. He points out that most books on morals and ethics by white Christians don’t even really discuss policing (He mentions Richard Hays’ book on New Testament ethics which I have read). His work on this area is thoughtful and eye-opening.

Overall, this is a fantastic book. Highly recommended. -

If nothing else, this was a great opportunity for me to see Biblical interpretation through another person’s eyes as they ask the questions necessary to read the Bible in their own unique situations. It highlights for me how my own background has shaped my biblical worldview. And that this study of black interpretation comes from a conservative, biblically-sound Bible scholar (and on top of that a student of one of my heroes, NT Wright) made this something I was eager to jump into.

The opportunity to see the Bible through another’s eyes was reason enough, but this book was also just full of interesting biblical insights, some of which I would have never noticed outside of someone else’s lens. An example from chapter two:

I have always been wary of the term “Under God.” To me it’s a reminder of how the American church has bought into the historical myth of a “Christian nation” and how it’s hurt the church’s mission. So I’ve always kind of ignored the term. But black interpreters of scripture have never had that luxury. Over the course of American history they have had to wrestle with what it means that God is sovereign in the affairs of nations, and how Romans says he sets up governments for his own purposes. It’s now apparent to me that in my denial of Christian nationalism I have also thrown out the idea of Christ’s sovereignty over government.

That’s just one example. Seeing the Bible through this perspective was enlightening in other areas as well - Mary’s prayer in Luke 1, the baptisms of John, the witness of Simon and Rufus, and an interesting take on what I already thought were revolutionary writings in Philemon. I have been studying Revelation 7 for years, but I still missed a jaw-dropping fact about identity that McCaulley saw because of how his background affects the way he approaches the Bible.

So I’m giving this five stars even though it is not a perfect book. Sometimes his arguments are stretches, and theologically there is nothing here that is groundbreaking. But theology wasn’t really his mission. In the introduction he sets up his goal:

“We are thrust into the middle of a battle between white progressives and white evangelicals, feeling alienated in different ways from both. When we turn our eyes to our African American progressive sisters and brothers, we nod our head in agreement on many issues. Other times we experience a strange feeling of dissonance, one of being at home and away from home. Therefore, we receive criticism from all sides for being something different, a fourth thing. I am calling this fourth thing Black ecclesial theology and its method Black ecclesial interpretation. I am not proposing a new idea or method but attempting to articulate and apply a practice that already exists.”

Note: As other reviewers have mentioned, the audiobook is not great. I made it about a third of the way through and switched to the paperback and I’m glad I did because I was also missing out on the footnotes. -

Simply amazing.

-

This book is about hope. It is deeply theological, but also full of practical compassion and wisdom, made all the more compelling by the author’s inclusion of bits and pieces of his own story. The way McCaulley flips abused biblical passages around, showing God's heart for liberation, is both academic and beautiful.

I believe this book will continue needed conversations within the Church. McCaulley says that he has "succeeded if [his book] has reminded others of home." Reading While Black truly provides us an "exercise in hope," I was humbled, challenged, and moved by it. -

We all read the Bible from our own viewpoint, from within our own culture and background. Our circumstances make us ask certain questions we wouldn’t ask otherwise. We could consider this a disadvantage. How could we know what the Bible really said when we are inevitably limited? But what if this were a blessing? What if this drawback allowed God to speak with truth and power to our particular situations?

Consider Martin Luther. His context of an often legalistic and corrupt church made him ask certain questions of the Bible about salvation. Or Dietrich Bonhoeffer. His experiences with the black church in Harlem and Hitler’s regime in Germany drove him to ask certain questions about how Christians and the church should relate to the government. Their answers did not encompass all the Bible said, but they were true.

This is what Esau McCaulley offers in Reading While Black. He found himself both feeling at home and not feeling at home with black and white progressives as well as with black and white evangelicals. Could he forge a new path that was unapologetically black and unapologetically orthodox? With pain and hope he points the way to true answers.

Several years ago, when I heard Esau McCaulley offer initial thoughts on a theology of policing, I thought, “What an amazing, creative question to ask, and what an intriguing, substantive proposal he makes!” In this book McCaulley also asks: How should the church offer a political witness? What is a full-orbed view of justice? How can Blacks gain identity from Scripture? What should Blacks do with the rage they feel from the injustices they’ve experienced? Does the Bible justify slavery as some contended for centuries?

The insights he offers to these are many and stirring. For example, he reminds us that Romans 13 is not the only passage about attitudes toward government in the Bible. In Luke 13:32-33 Jesus shows no deference toward a particular ruler. In Luke 1:51-53 Mary looks forward to governments which are not run by prideful men but which help the poor (echoing Isaiah).

He also highlights the beginning of the fulfillment of God’s promise that all nations would be blessed through Abraham when Jacob adopts Joseph’s two sons (his two biracial, half-African sons!) as his own in Genesis 48:3-5. Can those of African descent especially find their place in God’s promises? Indeed!

Then there is the question of black rage. I found his thoughts on the psalms of lament and imprecatory psalms to be some of the most powerful reflections he has to offer in the book.

The answers that Luther and Bonhoeffer found in the Bible are true—but they aren’t exactly the same. McCaulley simply asks for the same privilege that was accorded these gentlemen to struggle with difficult texts and difficult contexts.

Yet if everyone comes to the Bible from a different place, how can we know what it really says? Should we stop asking what the central message of the Bible is? McCaulley says no. We should instead ask (as he does) which understanding “does justice to as much of the biblical witness as possible. There are uses of Scripture that utter a false testimony about God.” (p. 91).

Esau McCaulley wrote this important book for himself. As a result he has also written a necessary book for all of us.

—

I received a complimentary copy of this book from the publisher. My opinions are my own. -

This book is not written for a reader like me. Sometimes this can be a bad thing, but in this case the fact that the book is not written for a reader like me is a very good thing. What this author did that is rare in books I have read that deal with matters of racial politics and identity is avoid a false dilemma between the desire for justice and a belief in the truth of the Bible. The author comments that this false dilemma often comes from the cultural politics of the Bible in the white churches (although it is no less a false dilemma there--God is just and His word is reliable and relevant to our behavior), and the author wrestles with the demands of God on believers that are particularly hard to the black experience, including the need to forgive so that one be forgiven. While I do not share the perspective of the author in a wide variety of ways, I can find no fault in an author who seeks to avoid false dilemmas and who wrestles with what God's laws and ways mean to their own life and their own experiences. I am not sure that my praise would mean all that much in such a case, but this book earned my respect because of its honest wrestling and its taking of both God and history seriously.

This book is a relatively short one at a bit less than 200 pages. The author begins with acknowledgements and then moves to discuss the need to make space for black ecclesial interpretation (1), where the author wrestles with the false dilemmas that often exist between conservative and progressive interpretations of the Bible. The author then discusses the sensitive issue of policing while looking at the New Testament's comments about the role of the roman army, a thoughtful and perceptive perspective (2). The author then deals with the question of the political witness of the church as it is recorded in the New Testament (3). After that comes a look at the pursuit of justice insofar as it relates to the black experience (4) as well as the Bible. This is followed by a chapter that looks at black identity, showing how the author can feel proud because of the African experience among early believers recorded in the scriptures (5). This is followed by a chapter that looks at black anger and the issue of forgiveness (6). The book then looks at the issue of freedom from slavery (7), concluding with an exercise in hope, along with an appendix that gives some notes on the development of black ecclesial interpretation (i), a discussion guide, bibliography, and two indices.

What I found most interesting about reading this book is that I respected the author most because of how seriously he took the Bible while the people who saw me read this book while I was eating dinner wished to praise me for being a progressive in being interested in matters of racial justice. It seems that there is a great disconnect between what this author is saying and what his message and perspective mean to an outside, white audience. This is a book written by a black man about the black Christian experience and how the Bible is immensely relevant, if complicated, to the black experience. I don't think the author is writing for white audiences or particularly cares if this book is appreciated by whites, and I think that is for the better. The basic similarities in the style of close reading and seriousness in interpretation between the author and myself are not something that would come across as well if the author were directly aiming for white (and most likely Progressive) readers. And I suspect that if other people who take justice and the Bible seriously (and I know such people) read this book, I think they will be pleasantly surprised and pleased by the honest wrestling of the author with what the Bible means for the contemporary black church. I just wish more authors would adopt some of the approaches that this author does that make this book a far better book than I had any reason to expect it to be. -

Despair has been my constant temptation in 2020. Do I even have to say why? Family crises compounded with....*gestures* everything have led to a less than positive outlook on many days. Hope has been somewhat elusive, so Reading While Black immediately appealed to me, in addition to the fact that McCaulley is now a (broadly speaking) local author for me, and is a priest in the denomination my husband and I are joining.

Reading While Black is a compact, concise text on Black biblical interpretation. McCaulley is an accomplished NT scholar, but also a boots-on-the-ground minister. These roles are never in conflict in his work. He sits under the text with all his lived experience as a Black Christian, and with his expertise in scholarship. Practically, this makes the text fairly easy to read (though I have a seminary degree and have had my share of Greek and NT classes, I am in no way a biblical scholar), yet researched enough to participate in more scholarly studies. Besides the intention of the book for Black Christians, it could be a useful supplementary text for, say, college courses on the New Testament or biblical exegesis.

Chapter topics include a New Testament theology of policing, the Bible and Black identity, and the Bible and slavery. Any of these chapters could easily be their own book, and McCaulley hints at a monograph on the theology of policing (hasten the day!). I appreciated McCaulley's choice to limit the scope of the chapters, to provide an elegant yet filling meal in each one instead of overwhelming the reader with an all-day buffet. Sine my masters' thesis covered the topic, I was particularly interested in his chapter on the Bible and American chattel slavery. My "critiques" for that chapter are summed up in "but I want more!" That's a fine place to leave a reader. He leaned on James W. C. Pennington, a Black minister and abolitionist, in this final chapter, which beautifully fulfilled McCaulley's goal of attesting to historic Black Christian exegesis, and the Black ecclesial experience.

Recommended by everyone from N. T. Wright to Lecrae, from Charlie Dates to Tish Harrison Warren, I too humbly submit my recommendation. McCaulley's reading of the Bible is faithful, humble, and invigorating. I look forward to reading more by him in the future.

"If the Scriptures were fundamentally flawed and largely useless apart from mainline revision of the text, then Christianity is truly a white man's religion. They were reconstructing it without my consent. Moreover, the form of this reconstructed religion bore the image of the twentieth-century European intellectual." (8-9)

"Psalm 137 is not merely a shout of defiance. It is a prayer addressed to God. Traumatized communities must be able to tell God the truth about what they feel. We must trust that God can handle those emotions." (126)

"We have allowed man made (I use the term man intentionally) rules to create a hermeneutical prison that traps biblical scholarship in the past. It is time to let the lion out to hunt. Ethnic identity and the Christian community, a question asked and answered a generation ago must be addressed again in our day so that our people know that God glories in the distinctive gifts we all bring into the kingdom." (166-167) -

McCaulley's book, which is largely a discourse focused on biblical interpretation as it relates to the specific experience of African Americans under slavery, and its ongoing effects, suffers tremendously because McCaulley's attempt to provide the parameters for a "located" hermeneutic avoids actually discerning present black experience on the topics discussed (the most specific chapter focuses on policing of black people; the others are much more general in scope, including black political witness, pursuing justice, black identity and rage).

One quote is sufficient to make this book plummet in my estimation: "This fear [that blacks have in regards to policing] might seem unwarranted to some. I am tempted to list statistics about Black folks and our treatment at the hands of the police. But I am skeptical that statistics will convince those hostile to our cause. Furthermore, statistics are unnecessary for those who carry the experience of being Black in this country in their hearts. We know, and this book is for us," (41). In other places McCaulley is glad to make a point without pages of substantiation. That is fine; this is a popular level book! But usually he does a good job providing references to works he has in his mind that he follows (see for instance his discussion on the last chapter about OT slavery and its difference from modern chattel slavery. This example, too, however, I'm inclined to think is a large oversight to glance over). In the quotation above McCauley gives no references and this is not something easily overlooked especially when a "located" hermeneutic must take present black experience into mind. The huge question is: what happens if your "located" sense of a group is wrong, even partially wrong? A located reading, a reading that relies upon such a thing as a monolithic black group consciousness, must describe that consciousness not only in the past (as that consciousness relates to real events/encounters with powers) but it must also do so in the present. Otherwise, the past can turn into a type of sounding board for present predilections and actually create worse conditions for those one is trying to serve because getting the truth wrong on a present subject like policy brutality could certainly precipitate in worse outcomes socially. Again, no mention of Thomas Sowell, who is the greatest economist on race this nation has seen; until he gets a hearing, until his voice is combatted, I'm not sure that books like this are fruitful to providing any clarity in these discussions.

All that being said, this book deserves another read from me for many reasons, perhaps most because McCaulley, neither distances himself from movements like BLM nor denies his evangelical (and Anglican! Awesome...) heritage. Thus it makes for a much more complicated read than the average 2020 racialized texts which paint in black and white. In other places McCaulley has interacted with Critical Race Theory, which I appreciate, because he doesn't shy away entirely from counterarguments. That this book is getting almost fives across the board and that one commentator in the front cover says, "Mark my words: Esau McCaulley is the brightest theological mind of this generation" strikes me as another example of the power that culture has to flatten or bloat opinion, certainly the latter is happening with regard to this book. -

I first heard of this author while listening to the Jude 3 Project podcast. Each time the author appears on the podcast, his views are always insightful so I was excited when I learned he was writing a book.

In this ambitious book Dr. McCaulley answers an intriguing question, how does Black biblical interpretation address issues facing Black people. He focuses on the specific issues of policing, politics, justice, identity and anger. Additionally, he gives biblical history and context as he breaks down how to view biblical passages through the lenses of these pressing issues.

This book is fundamental for anyone who studies and practices apologetics, defending one’s faith. This is also a great resource for those who are constantly looking to answer the question, is Christianity a White man’s religion?

I was given the opportunity to review an advanced copy of this book via NetGalley. -

I've failed to read much from Black theologians and pastors. That's something I'm ashamed of and am trying to correct. Thankfully, this was a great starting place.

McCaulley asks hard questions and in looking for answers in Scripture he was both patient and faithful. As a result, I learned a lot. Not because he conjured up new theories out of midair, but because I (in my cultural and experiential background) never asked the questions our African American brothers and sisters have been forced to wrestle with.

Favorite Quote: Colorblindness is sub-biblical and falls short of the glory of God. What is it that unites this diversity? It is not cultural assimilation, but the fact that we worship the Lamb... He is honored through the diversity of tongues singing the same song. Therefore inasmuch as I modulate my blackness or neglect my culture, I am placing limits on the gifts that God has given me to offer to his church and kingdom. -

I kept wanting to meet the author and thank him. What a great thinker. The exegetical work he does here, partnered with his shared experience as an African American, point to a well-earned faith. He looks at those experiences chapter by chapter and shows that God has always been and still is the answer. Behold, he makes all things new!

-

About a year ago, I first heard of Esau McCaulley. I do not remember if I heard of his new appointment to Wheaton College New Testament faculty (my alma mater) or if I saw him at the

Jude 3 Conference first. Regardless, I have paid close attention to him since. He has written many articles this past year for

Christianity Today (including this

month's cover article on policing adapted from this book), the

New York Times (where is he is contributing opinion writer),

Washington Post, and others. And he had an

interview podcast with ten episodes so far. I am also about halfway through

a free podcasted seminary class, The Bible in Color, which has some overlapping content with the book. My point of noting all of this is that once you have read this book, there is more to follow up with. And that I was not entering the book brand new.Reading in Black is not trying to survey the entirety of Black biblical tradition of biblical interpretation, but to give an introduction to the fact that there is a diverse tradition of biblical interpretation that matters. The book opens to tracing, somewhat autobiographically, why the Black biblical tradition matters. And the book ends with a 'bonus track' on some of the development of the academic Black biblical tradition. And he notes that the three general streams of the black church "revolutionary/nationalistic, reformist/transformist, and conformist" tend to only include academic expressions of the first and the last. McCaulley is more in the middle and wants to encourage more work in that reformist/transformist stream. Part of that first chapters that I have seen myself, is how important it is to be historically conversant in the actual words of the Black church, not just what has been said about those words.

Between that opening and closing are five chapters that illustrate what it means to interpret the bible as a Black man in the Black church tradition. The chapter that was developed into

the article at Christianity Today, is an exploration of the New Testament and the theology of policing. It centers around Romans 13, the passage that is frequently trotted out as a basis of supporting the political status quo, and shows why social context matters, but also how social context is not the only thing that matters when reading scripture. (That last bonus chapter explores the limits of social context in biblical interpretation more.) The Black church tradition has emphasized that the bible is not a string of proof texts, but an overall narrative that centers the liberating work of Christ throughout history. This means that interpreting Romans 13, apart from the reality that the subjects of authority are still made in the image of God, impacts how we see justice. Abstracting authority from the imago dei allows us to support dehumanizing tactics by removing the humanity of the subject of the authority from the ethical discussion.I do not have time to get into each chapter, but the other illustrating chapters discuss, the political witness of the church, the pursuit of justice, Black identity, Black anger, and slavery. All of these subjects are worth reading, and the content is very accessible and treated in enough depth to get an introduction to the concept but, not so deeply to go over the head of most lay readers.

One of the messages that came through clearly in the book was that because of a lack of familiarity with the Black church tradition, that many institutions, which are predominately white Christian institutions, force students or staff or participants in the Black church tradition to be conversant in white Christian biblical interpretation, and then rely on those students or staff to learn more about their own Black church tradition on their own. One story McCaulley related was about speaking to a group of COGIC pastors who lamented that they could either send their seminary students to Evangelical seminaries which would teach them to ignore the historic practices and social integration of the Black church, or they could send them to more liberal mainline seminaries which would take more seriously the Black church social tradition, but teach them to discount the theology of the Black church. And further, internal Black church discussions of theology are often stripped of context by white listeners and used as a method of delegitimizing the Black church as a whole.

The point of this book seems to be to introduce the tradition of Black biblical interpretation to not only Black Christians but for all Christians. And it was an excellent introduction. The chapters are short, and I think it would make for a great small group discussion (there is a discussion guide at the back of the book.) And there is a strong hint at follow up book(s) that explore other areas and more of the historically Black church tradition. There is a significant discussion right now about what justice means in the church. And too much of that discussion is lacking in historical and theological context. Reading While Black is a helpful addition to that discussion and I encourage you to follow not only Esau McCaulley but many other Black church advocates (like

Isaiah Robertson) that are rightly pointing out that the part of what is needed in a divided white evangelical church is a more robust understanding of what it means to be the church and the Black church tradition can help speak into that context. -

This was fantastic. McCaulley really carves out a place for himself, humbly refusing to say things for conservatives to use to push back against progressives, while also refusing to say things that would earn him the praise of the progressives who only seek to lift up black voices that agree with their own. One can only read and learn.

His presentation of black ecclesial tradition was succinct and provoked all the thoughts, especially his exegesis of Romans 13. It has traditionally been read as a mandate to individuals, but he maintains that Paul is concerned with governments and draws parallels between today's police and Roman soldiers. I will have to think about this more, and maybe even email him because this is still not quite clear to me. Still, it is very interesting to think about. -

I enjoyed this read by Esau McCaulley. It is crucial to find a balance between being critical of your cultural reading of Scripture while maintaining your high view of it. McCaulley does an awesome job in bringing to light a Black reading of Scripture, while challenging the majority culture to appreciate the text in a certain light.

The main idea: the Bible was not written by white people, so be careful to not assume your interpretation is accurate by itself. -

Esau does a phenomenal job of exploring the intersection of the black experience and Christianity/Holy Scripture. As someone who is committed to the Church and the stewardship of God’s word, he draws his readers into the complexity of a conversation that is centuries long without losing them in any high-academic tone. This book is extremely grounded and timely for our cultural moment. Could not recommend it more. Absolutely phenomenal.

-

I loved this a lot. McCaulley brings important, relevant, socially-located concerns to the Bible while engaging with a careful and close reading of scripture. One of the many things that this book did for me was add the third voice of the black ecclesial tradition to the dichotomy of the white progressive and white conservative traditions. This was a blessing to my understanding of the black church as well as my own reading of scripture!

-

I am always humbled to read from brilliant minds and compassionate hearts such as Esau McCaulley. This book is both informative and compelling. I learned so much not only from McCaulley’s owen experience but from his thorough and thoughtful analysis of scripture, church history, and society. I cannot recommend this book enough. A needed reading for white Christians, and I imagine a healing one for our Black sisters and brothers.