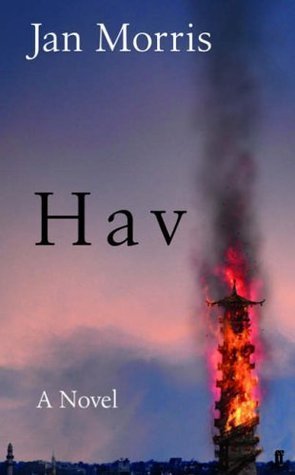

| Title | : | Hav |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0571229832 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780571229833 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 301 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 2006 |

| Awards | : | Arthur C. Clarke Award (2007) |

When Morris published Last Letters from Hav in 1985, it was short-listed for the Booker Prize. Here it is joined by Hav of the Myrmidons, a sequel that brings the story up-to-date. Twenty-first-century Hav is nearly unrecognizable. Sanitized and monetized, it is ruled by a group of fanatics who have rewritten its history to reflect their own blinkered view of the past.

Morris’s only novel is dazzlingly sui-generis, part erudite travel memoir, part speculative fiction, part cautionary political tale. It transports the reader to an extraordinary place that never was, but could well be.

Hav Reviews

-

Welsh travel writer Jan Morris imagines a tiny peninsula in the Mediterranean, a city-state by the name of Hav.

Jan Morris spent six months in Hav in 1985 and she returned for six days in 2005. Part One of her book provides a month by month account of her time in 1985 while Part Two is day by day in 2005, all in exquisite detail as Jan Morris includes enough information, description and insight to fill three hundred pages.

Thanks to New York Review Books, I recently joined Jan Morris for three weeks in Hav. What a country! Of course, for a full account, you will have to read Jan Morris' book for yourself. But what I can do is share a number of highlights from my trip.

Like any traveler, real or armchair, I'll turn the spotlight on what I found particularly noteworthy. And since, for me, the arts and literature are the thing, I put together the following slide show:

Trumpet in the A.M.

A trumpeter greets each day not with a blaring reveille but a plaintive lament. I hesitate to say dirge but each time I was roused from sleep, those notes possessed such a mournful quality, I wouldn't be surprised if a number of women and men were moved to tears. As I understand, this music on trumpet has a history going back to the European Middle Ages and involves a bloody conflict between Christians and Muslims.

Hubble-bubbles and Much More

Crack of a crisp, clear 6 a. m. and I'm down by the water at an open air market reminding me of Baltimore Inner Harbor or Fisherman's Wharf San Francisco. Absolutely everything is for sale: spare parts for cars and trucks, rolls and rolls of silks, apples, casaba melons, coffee beans, meat on hooks, ponchos, shoes and, of course, second hand books- one great find - a copy of Moby Dick with 'Property of the American University, Beirut' stamped on the inner cover. We should anticipate seeing all the world's goods on display in the Hav market since, after all, among the city-state's population: Turkish, Arab, Greek, African, Armenian as well as Russian, German, English, French, Italian, Spanish, Swiss.

Viewing Rainbow

If you like watching TV, you're in for a treat and it doesn't matter what corner of the globe you happen to be from. In Hav you'll have an opportunity to watch old Hollywood movies in Turkish, the most recent American soap operas in Arabic, talk shows in French, Italian, English or Chinese. I even caught a replay of a soccer match with Pelé in Portuguese with Russian subtitles.

Gala Events and Red-letter Receptions

Positioned as it is at the crossroads of East and West, as a geographical hub for various cultures, Hav has hosted receptions and grand balls for Russian nobility, world leaders, famous artists and writers, Leo Tolstoy among their number. Also of special note: Rimsky-Korsakov, a naval officer at the time, became so enchanted with everything he saw in Hav that he was inspired to play one of his own compositions on a grand piano in a prominent Hav garden. Then, years later, he adapted the melody the Hav trumpeter played at dawn for the recurrent theme in his Scheherazade.

Chance Meeting

Sipping Turkish coffee at a coffee shop in the old district, Jan Morris and I had the good fortune to meet novelist Armand Sauvignon who came to Hav from France in 1928 and has remained in the city-state ever since, a man currently in his eighties with a long beaky nose, creased brow and sharp gray eyes that combine to give one the impression he's looking out at the world in continual irony. Armand Sauvignon was gracious enough to write his name in the notebook I had with me. The next time I returned to the Hav market, I searched out a bookseller displaying a Armand Sauvignon novel (actually, she had five English language novels of his for sale). I made the purchase and scotch-taped the author's signature on the title page. Incidentally, the novel is Returning, the saga of two aristocratic families that's set in a fictional Polova that's really Hav.

Souful Geometry

The newly constructed section of Hav (New Hav) is breathtaking in its symmetry, as if an exercise in geometry, Mies van der Rohe meets Buckminster Fuller. As Jan Morris writes, "The city was supposed to be a physical representation of the cooperation, of unity in variety. Its circular shape was meant to symbolize eternal peace, and each boulevard was planted with a different species of tree (planes, catalpas and ilexes) to express the joy of amicable difference."

Maximal Splatter Sport

No account of Hav would be complete without reference to a May 5th event that takes extreme sports to unfathomable limits: the Hav Roof-Race. Here are the words of Jan Morris on this death-defying spectacle originating in the 16th century:

The Roof-Race (author's caps) begins "with the scaling of the city wall, beside the Market Gate, and it entails a double circuit of the entire Medina, by a different route each time, involving jumps over more than thirty alleyways, culminating ina prodigious leap over the open space in the centre of the Great Bazaar, and ending desperately in a slither down the walls of the Castle gate to the finish. The record time for the course is just under an hour, and officials are posted all over the rooftops, beneath red umbrellas like Turkish pashas themselves, to make sure there is no cheating."

For hundreds of years, the race was run at midnight but so many runners (usually about 50 runners run the Roof-Race) were maimed or fell to their death, in 1882 the Hav leaders, Russians at the time, shifted the race to dawn. Evidently many of the Hav youths disapproved of the switch - they derived great delight from watching splayed bodies of runners falling through the street-lights to their deaths. Oh, well, at least nowadays those youthful souls can record Roof-Race deaths on their cellphones.

To read all the juicy details, run to your nearest bookseller (or computer) and start reading this New York Review Books edition beginning with an informative introductory essay by Ursula K. Le Guin. Travel writing has never been more imaginative.

Welsh author Jan Morris, 1926-2020 -

There are two works here: Last Letters from Hav, first published in 1985, followed by Hav of the Myrmidons, a sequel published twenty years later. I will speak of them separately.

LAST LETTERS FROM HAV:

They say that Hav is not real, that there is no city, no country named Hav. True, travel agents have been asked and ingloriously failed to get folks there. And the author's descriptions and such maps as she provides are, well, wanting. It is close by Montenegro, we know that for sure, but we can't say, precisely, what it abuts. There are sea routes to Greece, train services to Moscow. Yet, you won't find it on a map. Google, Siri, Alexa - they can all tell you who put the bomp in the bomp bah bomp bah bomp, but they're stumped, it seems, on where Hav sits. But Pliny was there. The First Crusaders too. Much later, Chopin came with George Sand and lived, as they say, in the Armenian way. James Joyce, instead, hung with other writers. Richard Burton, the explorer, went entirely Arab. Freud studied eel testes, this before he developed the castration complex. It was there that Rimsky-Korsakov wrote Scheherazade. Hitler's quick visit - he never left his touring car - is thought to be apocryphal. The minarets might make you think of Istanbul, but there are clearly Western influences, and Asian, too. It is a place where every religion seems to dominate, yet Hav is not religious, they say.

Too much, you say, to believe. As if Hav is some invented microcosm of history, geography, biography. The author, herself, called Hav a jumble and a hazy allegory. Aren't all allegories hazy, I ask.

A repository, I'd call it. As I am.

They say that Hav is not real. They say that . . . but I don't believe that. Because there was this:

Tramp steamers of a kind still come, and perhaps bring poets sometime.

The tramp steamers are vague of distinction and improbable of cargo. I know that's true. And if, indeed, tramp steamers come, then there is a good chance a friend will be there, high on the mast, a lookout. If he does not, perhaps, bring a poem, he will, instead, bring his prayer. And that is real enough for me.

HAV OF THE MYRMIDONS:

Jan Morris, modestly claiming no prescience, wrote that the brooding sense of foreboding - (in her Last Letters from Hav) - erupted into catastrophe on September 11, 2001. Okay, maybe not so modestly. Last Letters does have a kind of cataclysmic ending. Hazy, though.

And so, a sequel. (Which, by the way, didn't Airplane II, Caddyshack II and Dumb and Dumberer to teach us anything?)

Hav of the Myrmidons moves us into Dystopia. Morris misses the old ways, even imagined ones. She paints a bleak picture, which of course is not unusual in dystopian art.

The (to my eyes) architecturally beautiful House of the Chinese Master of the first book is destroyed, replaced by The Myrmidonic Tower of the second book. The Tower- TOWER - is monolithic, very high, with a giant M on top, maybe for Myrmidon, maybe for Monsanto, Morris says. Regardless, it is a gaudy symbol for both power and plasticity.

And what of the new Hav, really?

The facts are . . . that there are no facts. Facts are factotum in the new Hav. Facts are faxes. Faxes are facts. Fair blows the fact on summer eve, and fierce the mountains fart. . . . There's a lot to be said for the Republic. It's certainly better than what came before. You may question the taste, but you can't deny the speed and efficiency of the recovery. Hav is certainly richer than it was before, and much better ordered. . . . What we object to is this: that it's all based upon lies.

Some of you will no doubt say that Morris, in 2006, had not lost any of her prescience.

So, is Hav real, after all? I don't know. I thought it was but now I'm not so sure. No tramp steamers come to port in the second act, no Gaviero with a better view. -

Morris, most everyone knows, is one of the premier travel writers of the 20th Century. She went everywhere, and wrote with such interest and erudition about the places she visited that one reads her works simply because she writes better than anyone else. One publisher gave her the opportunity to write fiction, and Morris created an invented place, Hav, to which many folks immediately wanted to book a flight.

This novel is composed of two parts: in Last Letters from Hav Morris describes for us her first glimpse of the Protectorate of Hav, its residents, flora, fauna, religions, and origins. In Hav of the Myrmidons written twenty years later, Morris returns to a much-changed Protectorate. In the Epilogue to the combined novel called simply Hav published by

nyrb, Morris tells us that the allegories of old Hav have been transmuted from a place of “overlapping ancient cultures but with familiar signposts based in history” to allegories of “civic prodigies…hitherto inconceivable and themselves all but fictional still.”

Hav is an international protectorate near the Black Sea and on the Mediterranean. Every major nation had its representatives there, ensconced in (formerly) grand buildings that carried a storied history. When Morris visited in the 1980’s, Hav was rundown and a tiny bit disreputable, but the glamour of earlier days still shone through.

Morris shares her first impressions upon her arrival at night (monotonous and cold, stark and forbidding) and those again modified by clear morning light (bright, colorful, polyglot). She stays several months, buys an automobile, and travels by ferry to outlying islands. She meets the important citizens and legal representatives of countries occupying national concessions in Hav and witnesses the major celebrations—the coming of the snow raspberries and the Roof Race. Her visits to The Iron Dog, and The House of the Chinese Master (“the most astonishing aesthetic experience Hav can offer”) are accompanied by marvelously detailed descriptions composed of wonder and awe.

The novel is just a travel memoir, a very good one with historical references and informative notes about where to find the best food, until Morris comes to her discussion of the British Concession and its history in the province. Morris seems to become much more pointed in her references when she describes the British consul, his wife, and English interests in establishing a base in Hav. Morris includes notes General C.J. Napier wrote to his wife about Hav: “A dreadful hole—worse than Sind!” and “Oh what a foretaste of hell this is.” The British always kept some distance from true involvement in the life of Hav (they “loathed the Protectorate”), created buildings that looked quite like those created in India for their comfort, and were reputed to house only spies in their offices.

We learn that celebrities and leaders from many countries visited Hav in its heyday. Morris’ description of Nijinsky’s visit is particularly poignant, but Hitler and Wagner (at different times, naturally), George Sand and Chopin, Kim Philby, and the shadowy Sir Edmund Backhouse, scholarly sinologist and baronet, were all said to have stayed there at some time or another.

An escarpment just to the north of Hav was home to a cave-dwelling tribe of troglodytes who never settled in the city proper but who form “a still living bridge between the city and its remotest origins.” Their language has a fragile connection with the Celtic, but is still incomprehensible to everyone outside their group. It is said when they first saw the peninsula upon which Hav now sits, surrounded by blue sea, they called the place “Summer,” or hav in the surviving Celtic language of the West.

The underlying political structure of Hav was a shambles of competing interests and insufficiently expansionist beliefs which added to the rich confusion of organic growth in the labyrinthine city. Hav was likewise a rich stew of religions, all in stages of isolation from their original tenets. One mysterious group called Cathars of Hav was composed of secret members of the community and whose ceremonies and meetings involve robes and chants in underground locations. The Cathars are said to trace their history to the Crusades and their beliefs to Manicheanism, or the dualistic cosmology between the forces of good and evil, darkness and light. This group alone gives Morris pause in her ramblings about the city, but she does not spend much capital thinking about them before she is advised by the British Consul to leave the city in haste.

Morris ends Last Letters from Hav on a note of uncertainty, with low-flying war planes streaking over the city. Morris sees warships on the near horizon as she pauses on an overlook near where she will abandon her vehicle and catch a train away from Hav.

Morris uses the word “maze” to describe Hav more than once, leading us to think she meant, among other things, to suggest “a-maze…ing” Hav. In 2005 Morris was invited to revisit Hav. Her later map of the city looks completely different from the earlier one, with many of the wonderful places she described razed. Now the Myrmidon Tower dominates the landscape: “a virtuoso display of unashamed, unrestricted, technologically unexampled vulgarity” upon which is emblazoned the state emblem of the Republic, the letter ‘M’ flashing in sequential colors of red, yellow, green and blue and overlaid against an Achillean helmet outlined in gold. When Morris ascends the Tower, she discovers the nearby newly constructed Lazaretto! Resort (“the name is written with an exclamation mark because we believe you will find it a truly exclamatory experience”) is, in fact, built like a maze when viewed from above. The suites are named for places once a part of the old Hav before the Intervention in 1985.

As luck would have it, the first people Morris interacts with in the New Hav are a “very English middle-aged couple” whose advice “don’t experiment too much with the local stuff” seems designed to remind Morris however things have changed, much has stayed the same. But then: “The thing is one feels so safe here. The security’s really marvelous, it’s all so clean and friendly, and well, everything we’re used to really.” And that turns out to be the most frightening and curious thing.

The troglydytes who originally named Hav are no longer living in whitewashed caves on the escarpment but have been moved to barracks near the airport where the menfolk work on airport construction. While many Morris spoke with seemed pleased with the central heating and the comfortable living, one man pointed out that they were experiments of “ethnic engineering,” given a few certainties in exchange for their unique though hardscrabble culture.

Morris must leave after only six days this time, while she was forced to leave after six months on her first visit. Things have changed quite a lot and the menace is palpable. People are afraid to speak openly for a very tight grip by the Cathars of Hav hear all and see all.

This science fiction reminds us what a woman of the world Ms. Morris is, for she has caught the national character of each resident group in Hav quite clearly. But it is her certainty that events and locales have really lost their historical basis and point of origin is one that stays with us long after we put her book down. The world is renewing itself, and has become strange to even one so practiced in the art of travel.”The great ‘M’! ‘M’ for what? ‘M’ really for Myrmidon, or ‘M’ for Mammon? For Mohammed the Prophet? For Mani the Manichaean? ‘M’ for McDonald’s, or Monsanto, or Microsoft? ‘M’ for Melchik? ‘M’ for Minoan? ‘M’ for Maze?...’M’ for Me?”

Again from the Epilogue, Morris says “A whole world…has come into being since I wrote Last Letters from Hav. New states have emerged, and new kinds of cities suddenly erupted.” The world is a new thing in this century, and history doesn’t always provide a signpost. Morris, the great traveler, is perplexed and uneasy.

-

I have never, in my life, read a book two times in a row. Until I read Hav. This was possible because Hav is not a novel in the ordinary sense. It's a travel memoir to a fictional place that could easily exist; it's a meditation on East meeting West, on history and culture and modernity; it's about being a stranger in somewhere simultaneously familiar and alien. And it has some of the most wonderful prose I've come across.

This section from Hav illuminates many of the aspects that make the book so wonderful.

[The boats] often use their sails, and when one comes into the harbour on a southern wind, canvas bulging, flag streaming, keeling gloriously with a slap-slap of waves on its prow and its bare brown-torsoed Greeks exuberantly laughing and shouting to each other, it is as though young navigators have found their way to Hav out of the bright heroic past. (p66)

This. It's beautiful, for a start. It suggests that conjunction of somewhere existing both in the present and, somehow, in the past that makes Hav so intriguing. And it's quoted back at its author in the second part of the book, as an indication of her own understanding of Hav.

(We're all about the meta.)

Two thirds of the book was written and published in the 1980s. According to Ursula le Guin, who wrote the introduction, it led to people going to their travel agents looking to book a ticket to Hav because it was so convincing. Now, it really is convincing, but at the same time there are aspects that make it quite clear that Hav is a fiction. Like the fact that you've never seen it on a map, maybe? I was confused by that until I look Jan Morris up, and discovered that she has written many actual travel books (under that name and as James Morris). So I concede that perhaps if you knew her earlier work, you could be forgiven for some confusion if not quite that much. Anyway, the last third was written in the early 21st century, and sees Jan going back to Hav after the Intervention - which was just starting as she left last time. And this allows Morris to explore a whole other aspect of culture and development.

"Last Letters from Hav" are entries written between March and August, with Morris arriving in Hav at the start and being bustled out as trouble brews at the end. In between, she does what any travel writer does: she stays in interesting places, she visits the important and not-so-important places in the city, she talks to people, she reminisces about what other people have said about the place. I've been having a great deal of difficulty writing this review because the books is absolutely busting at the scenes with themes, with commentary, with historical (a)musings. There's multiculturalism and colonialism and identity - the losing and finding and historical nature of and doubt around. There's appropriation on a massive scale - see previous note - and getting on with the business of life. There's ordinary mystery and profound mystery, religion and politics and architecture and this book had me in RAPTURES. Can you tell?

Hav is a city-state in a world that really doesn't have them any more. It's got an uneasy relationship with Turkey, its only (?) land neighbour, but a seemingly thriving one with certain Arab nations and perhaps the Chinese. It's basically meant to be somewhere like the Dardanelles - although the geography isn't quite right - because it's a big deal that this was where Achilles and his Myrmidons came ashore. And the Spartans too, apparently. And, later, Arab merchants, and Venetian merchants, and it's one of very few venerable Chinese merchant settlements outside of Asia. See how Morris twists history and makes it just believable? There really were moments where I could believe this was real. Because her discussion of history is modern, too: the Brits wanted to colonise it; Hav was shared by France, Italy and Germany under a League of Nations mandate; Hitler might have visited, and Hemingway did. Morris talks to people who are flotsam from this era; and also to a man claiming to be the 125th Caliph. Also a casino manager, members of the 'troglodyte' race who live in the nearby mountains, the local philosophers, and some bureaucrats. She visits odd monuments, the Conveyor Bridge (I admit I had to ask someone whether that was actually possible, because I was teetering on the edge of What Do I Believe?), and the Electric Ferry. I don't believe that this book could have been written by anyone other than an established travel writer, because her eye and ear for (even imaginary) detail is breathtaking.

The second section is much shorter and deals with only a week or so, some two decades later when Morris is invited back to Hav after the Intervention. "Hav of the Myrmidons" does all of the same things as "Last Letters," with additional meditation on the nature of change and tourism and the impossibility of an outsider ever really understanding the internal workings of a foreign city. There's also the inevitable nature of change, and the sinister side of globalisation with imported labour and native populations made to relocate - which, intriguingly, is given a possibly positive spin. Morris' books is either revered or believed to be banned in Hav, depending on who she speaks to (it's one of the bureaucrats who reveres it that quotes the passage above at her, as part of the reason for why she was asked back). But things have changed. Most of the glorious many-centuries-in-one-place nature of former Hav is gone, replaced with new and forbidding and disorienting architecture. Like the massive Myrmidon tower, surmounted by an M - but no one really knows who or what the Myrmidons are, or meant to be, in this context. Some things of old Hav have been retained, but sanitised, bent to a new understanding of the world. Tourists are allowed, but only in a defined space - which leads to another bit I wanted to quote, because I think it's an indication of a travel writer's despair:

"The thing is... one feels so safe here. The security's really marvellous, it's all so clean and friendly, and, well, everything we're used to really. We've met several old friends here, and just feel comfortable in this environment. We shall certainly be coming again, won't we darling?" "Oh, a hundred percent. I think it's bloody marvellous what they've achieved, when you remember what happened here." (p196)

Thus spake an older English couple with no intention of leaving the resort.

Hav puts me in mind of China Mieville's The City and the City, and Christopher Priest's The Islanders, both of which do a similar thing with inventing places that ring so amazingly true. The Priest is clearly fictional but written as a travel book; the Mieville is a fiction but set in a city that purports to be real. I guess Hav conflates the two.

This review gets nowhere near what I really want to say about Hav. I am so glad that it exists, and that I have read it. And now I will force it into the hands of anybody I possibly can... although I admit to some trepidation that maybe other people won't like it as much as I do. (I haven't been able to look at any Goodreads reviews for that reason.) I may have used the word intriguing too many times, and I may have given in to hyperbole, but I don't care. I love this book and want to hold it to my heart FOREVER. -

Such a detailed imaginary travelogue, really worlding this imaginary Hav into history. It made me wonder how to take it even further, beyond the limits of travel literature.

-

This was somewhat interesting, but I'm not sure the of the point of it. I always feel with projects of this sort that I am wasting my time reading something informative in tone but non-factual in content. Essentially, why read a cultural study or travelogue about a made-up place when there are plenty of real ones about which I could be better informed. I am dropping this unfinished and will try something else by the author at some later date.

-

"The first album was better" in literary form. It always is.

-

An excellent example of that small sub-genre the invented place set in our own world.

Other examples I've read have tended to feel like a mish mash of existing places. This is different. Jan Morris really makes you feel like Hav is real and furthermore worth making the effort to visit (at least in its original form) -

(Originally published at

www.bookslut.com)

William Gibson writes of "a prose-city, a labyrinth, a vast construct the reader learns to enter by any one of a multiplicity of doors... It turns there, on the mind's horizon, exerting its own peculiar gravity... It is a literary singularity." This city seems to exist outside of time, yet moves within it. One can never be sure.

Gibson was writing about the fictional city of Bellona from Samuel R. Delany's Dhalgren, yet his words apply equally -- if not more so -- to another fictional city: that of Hav, the singular creation of the renowned and prolific Welsh travel writer, historian, and novelist Jan Morris.

Morris brought Hav into the world in 1985 as Last Letters From Hav, short-listed for that year's Man Booker Prize. She returned to Hav in 2006 with Hav of the Myrmidons, a single volume with a reprinting of the original Last Letters, which was a finalist for the 2007 Arthur C. Clarke Award. Now, the New York Review of Booksis bringing that combined volume to American readers under its Classics imprint.

Hav is a work of fiction unlike any other I've read. Narrated by the character Jan Morris, Hav unfolds entirely as a travel narrative, as seemingly veridical as anything Paul Theroux or Lawrence Durrell would pen. In fact, upon its publication, readers overwhelmed Morris inquiring where exactly Hav could be found, how to get there, whether a visa was necessary or not. Even the Royal Geographical Society wanted to know, according to Morris's epilogue.

Accordingly, the novel begins with Morris's arrival in Hav, itself hazily located somewhere on the eastern Mediterranean. She explores the city, a register of millennia of human history, founded by migratory Celtic tribes or ancient Ionians, perhaps by Achilles himself. Conquered in turn by Arabs, who held it until the Crusades intervened for a century, it served as the fulcrum of the Silk Road for four hundred years, at which point it passed into the hands of the Seljuk Turks, the British Empire for a short time, the Russian Empire until the Revolution, and a Tripartite Mandate of France, Italy, and Germany between the wars.

Its onetime visitors and residents represent a veritable who's who of world history and culture: Ibn Battuta, Hemingway, Diaghilev and Nijinsky, Mann, Freud, Cavafy, Churchill, Joyce, maybe Hitler, though that's far from certain. Every faith has a place here: from the Grand Mosque of Malik in the Medina, to the Greek Orthodox church on the small island of San Spiridon, to scattered Buddhist and Hindu temples, a synagogue, and churches of every Christian sect.

The reader follows Morris as she tries to navigate this unreal city, with its multifarious architectural styles, Babel of languages, mélange of smells and sounds. She familiarizes herself with its cafes, its music, its trademark urchin soup and snow raspberries. She attends the Roof Race (which is exactly what it sounds like), and her descriptions of the frenzy of the crowd tearing through the city to follow the athletes running and jumping across alleyways above is among the more riveting parts of the novel.

One could go on for some length and is tempted to, for Morris's prose is so resplendent and exacting in its erudition and craftsmanship. Her knowledge of Mediterranean history and culture shines through on every page, and her attention to seemingly minor details, such as witnessing two elderly Buddhist monks alone in a crowd of merchants purchasing saffron, for instance, preserve the veneer of an "official" travel narrative.

Ultimately, though, Hav is a place utterly fluid, where identity is consistent only in its Heraclitean flux. History swirls around Hav, yet always inchoate, subject to the whims, distortions, and sedimented agendas of countless peoples of countless factions over countless years. And like that other fictional city Bellona, Hav is a mystery in which nothing is as it seems -- or maybe everything is exactly as it seems until it changes into something else, until over time everything possible in human history has already happened, is still happening, and will happen again. Last Letters from Hav, indeed, ends with a cataclysm known as the Intervention, the details of which the reader is never entirely informed.

One is reminded of Borges's "The Library of Babel," and Borges's ghost clearly walks through the streets of Hav. This is mostly implicit in Last Letters From Hav, though Morris does inform the reader that "The maze is so universal a token of Hav, appears so often in legends and artistic references of all kinds, that one comes to take it for granted." According to Morris, "It certainly seems true that if there is one constant factor binding the artistic and creative centuries together, it is an idiom of the impenetrable... [The artists of Hav] have loved the opaque more than the specific, the intuitive more than the rational."

The connection to the concept of the labyrinth, both physical and metaphysical, is made far more explicit in Hav of the Myrmidons, in which Morris returns to a post-Intervention Hav that has been forever altered. Gone are the domes, spires, meandering streets, and chaotic din of old Hav, which have been replaced by a Chinese-financed "brand-new metropolis of mirror-glass, steel and concrete, metallic, regimented." The old city has been cut off from its garden island of Lazaretto, which has become a sort of contemporary Dubai -- a glittering playground of luxury designed for foreign nouveaux riches aptly renamed Lazaretto! Morris soon finds, however, that the seeming regimentation and rationalization of the city she knew has in no way reduced its vertiginous complexity.

The entropic despotism of old Hav has been replaced by a nightmare surveillance state styling itself the Holy Myrmidonic Republic, the symbol of which is a two-thousand-foot tower soaring above the resort of Lazaretto! and adorned at its spire by a giant illuminated M, which continually changes color. The new Hav, as is clear to Morris, is a complete simulacrum of a farce. The HMR prevents tourists from entering the old city (Morris has a two-week visa with an exemption, thanks to some old acquaintances), monitors every conversation, produces genetically-modified snow raspberries (in an Atwoodian touch, renamed "Havberries") with imported labor from Uzbekistan and Afghanistan to can and export, and has rewritten and whitewashed its jumbled history to present the most sanitary face to potential foreign investors.

While Hav of the Myrmidons feels a little too obviously polemic -- and perhaps that's because the current dystopian moment has witnessed Atwood's two most recent novels, The Hunger Games trilogy, and Super Sad True Love Story, not to mention the events of the six years intervening -- Morris's prose remains crisp and effusive as in the earlier work. If the allegory of Hav is that identity and history are just as malleable and in flux as topography, the two halves complement each other quite effectively.

Of course, Morris herself says in the epilogue that even she doesn't know whether an essential allegory of Hav exists, which is most likely the point. At any rate, this volume contains a lifetime worth of sensual experience, and some of the most luminous and unforgettable writing I have ever encountered.

Hav by Jan Morris

NYRB Classics

ISBN: 978-1590174494

320 pages -

A book that I feel was written, essentially, for me. Not in the sense of an upheaval-ing personal revelation, but one that deals with my adoration of esoterica of ongoing multicultural melting of people and ideas both modern and ancient. I think the first sequence of the story, Last Letters from Hav, is the more successful piece of writing. The second, Hav of the Myrmidons, is fascinating but feels a little less lovingly thought over. In any case, it's an extremely fascinating study of the collective consciousness of the city, and the author clearly understands the creeping dread of gentrifying forces in favor of more anarcho-libertarian pastiche. Here you find traces of Dubai, Brooklyn, or Sirte.

Small aside #1: As a fictional place, did anyone try to triangulate the physical and conceptual location of Hav from all of its cobbled descriptions? Did you come up with the Republic of Hatay and Antioch?

Small aside #2: There are a few editorial oversights that the editors should be advised to correct in Myrmidons -- Magda is at least twice called "Mazda," a missing space, a double period, a period in place of a comma, and instances of stray punctuation often enough to be noticeable. -

This is actually two separate books: Last Letters from Hav and its sequel Hav of the Myrmidons. In them

Jan Morris writes about an imaginary peninsula ajacent to Turkey that has a mixed population of Arabs, Greeks, Russians, Chinese, troglodytes (the "Kretevs"), and miscellaneous Europeans. Readers of

Hav have been so befuddled as to make travel inquiries.

A brilliant travel writer like Jan Morris can easily confuse the reader. Her picture of the old Hav is so appealing and the picture of the draconian changes after the "Intervention" which Morris flees in the first part and returns to twenty years later so realistic that the two books together can stand in for almost any small diverse country.

Although the Hav books are fiction, they can almost be read of the changes that are sweeping through the Eastern Mediterranean and other places due to politics and religion and the politics of religion. -

Jan Morris can really write. There is not much action in this book, and it is often hard to keep the characters in check, especially over the span of two separate books, but the level of writing is so high that none of that matters.

Moreover, I really enjoyed the allegorical implications of the book. First, as a node of mittle-Mondial (I made that up) mid-20th century history and culture: Russian aristocrats waxing nostlagic, English colonialism quietly ending, religions bubbling together while mysterious fanatical cults worship underground, and capitalism slowly pushes aside the cultural specificities which usually make a travelogue. The latter theme is the focus of Return of the Myrmidons, a scathing description of the speed and uniformity that globalism envelopes economies, politics, and culture in even isolated locales (perhaps even more effectively in isolated locales). Here we see the ugly world of billboards, corporate architecture, mod-coms and an almost sourceless censorship.

If you are not a travelogue reader this book may be difficult--but it is broad and stylish, and I suspect most will find it very good indeed. -

I read once that

Michael Chabon received many letters from people claiming to have been to Sitka, the imaginary Jewish-Alaskan setting of his much-acclaimed

The Yiddish Policemen's Union. Apparently the same thing happened to Jan Morris, the creator of the mysterious port city of Hav. Supposedly a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society asked her to point it out on a map. I'm not surprised; the first portion of this book especially is strongly reminiscent of

Janet Flanner's dispatches from Paris.

I adored the first book in this omnibus,

Last Letters from Hav. It establishes Hav as a marvelously real-feeling locale. While the story ends in a way that feels like an ending, the reader is left with a marvelous feeling of uncertainty.

Morris waited two decades (and change) to write a followup, Hav of the Myrmidons. In a way, it is more a coda to the previous volume than a full book per se. It reminded me of

Cyteen in places: the narrator racketing around, coming up against secrets that no one wants to speak about, unexpected limits to liberty.

If you have read the afterword to the trade paperback edition of China Mieville's

The City & The City, then you will understand why he says that his book is in dialogue with Hav. (Especially if you are aware of his politics; insofar as I understand them, I can see why it would rub him the wrong way.)

Speaking of such things, I recommend that you skip the introduction by Ursula K. Leguin until after you have read the rest of the book. You will have more fun that way.

Dates approximate. Re-read May 2013 and added a couple things to the review. -

Jan Morris aslında bir seyyah ve tarihçi. Bu kimlikleri onu elbette aynı zamanda bir yazar da yapıyor. Ancak bu defa gördüğü, tecrübe ettiği, gözlemlediği, duyumsadığı şeyleri birebir aktarmak yerine bir kurgu içerisine hapsediyor ve okurun önüne olduğu gibi bırakıyor. Ursula K. Le Guin bu durumu şöyle açıklamış: "Hav, tüm Akdeniz tarihinin, adetlerinin ve politikasının birkaç bin yılına tutulmuş bir ayna gibi..." Çok doğru. Bu ayna, gördüğü şeyleri çoğaltıyor, genişletiyor, görüntüleri birbiri üstüne bindiriyor. Kimi zaman çarpıtıyor, kimi zaman dosdoğru yansıtıyor. Kimi zaman güzellikleri kimi zaman da çirkinlikleri vurguluyor.

Ursula K. Le Guin bu kitabı bilim-kurgu olarak tanımlamış ve şunu eklemiş: "Ciddi bilim-kurgu eserleri hayal ürünlerinin değil bir gerçekçiliğin biçemidir". Nitekim bu tanımlama üzerinden gidersek: evet, Hav bir bilimkurgu. Ancak, bu noktada (niyeyse) hala çekincelerim olduğu da bir gerçek. Ne ölçüde bilim-kurgu? Bilim-kurgu nedir? İçinde bulunduğumuz coğrafyaya dair çok fazla bileşenle harmanlanmış bir tarihsel kurgu eser var karşımızda (sanırım ben daha ziyade bu şekilde adlandırmayı tercih ederdim).

Kitabın anlatım dili bir seyyah tarafından kaleme alınmış şekilde yazılmış. Kimi yerlerde sıkıldığımı itiraf etmeliyim. Kimi yerlerde ise merakla okudum. Kitabın geneline bakıldığında kurgusal aynı zamanda da tarihsel izleklere sahip bir gezi anlatısı olduğunu söyleyebilirim.

Özetle, kitabı önermek ve önermemek arasında gidip geliyorum. Kitaba karşı hala net bir fikir geliştirdiğim söylenemez ne yazık ki. Ancak farklı bir kitap olması nedeniyle tercih edilebilir. Sonuçta hep aynı şeyleri okumaktansa farklılıkları da gözetmek ve tecrübe etmek bizi biz yapan ve geliştiren şeyler.

Kitaplarla kalın! -

A literatura de viagens pode ser lida como uma elaborada forma de ficção. Afinal, que provas temos que um escritor este realmente no lá que descreve? Saltou de um avião para a poeira e arquitectura exótica ou reconstruiu na sua mente uma imagem de um além da fronteira a partir de imagens e leituras? Instintivamente sabemos que não é assim, não seria possível ser assim. E no entanto a literatura de viagens não é um retrato fiel de locais, é uma reconstrução feita a partir das percepções do vajante-escritor.

Ou então podemos ter algo como este intrigante relato a duas épocas sobre Hav, esse curioso enclave na costa turca. Como o descrever? Langor levantino com misturas de resquícios de impérios perdidos na história, onde seitas esquecidas ainda dominam o espectro intelectual e político. Não um cemitério de impérios, antes um daqueles portos que o devir hist��rico, as leis dos mercados e as andanças das gentes transformaram em mesclas culturais únicas. Pense-se uma colisão a baixa velocidade entre Gibraltar, Tânger, Malta, Rodes, Macau e o Mónaco e começa-se a conceber o carácter de Hav.

Como lá chegar? Apenas pelas palavras contidas entre a capa do livro, pois Hav é um local ficcional criado pela escritora de viagens Jan Morris para tentar, como observa no posfácio, dar sentido às experiências que relatava e mostrar que o mais arguto dos escritores não consegue dar a conhecer o carácter profundo das terras que visita e regista. A ficcionalidade de Hav, moderna Ruritânia, não impediu que curiosos viajantes se dirigissem a agências de viagem em busca de um bilhete para o enclave. Ficção, mais real que a realidade.

Hav vive de dois momentos: a descrição de um poeirento entreposto tradicional, langoroso e esquecido pelo tempo, e o seu perfeito contraste, uma reflexão sobre a hipermodernidade estéril de locais como Singapura ou Doha, onde o arranha-céus e o ar condicionado esmagam o carácter tradicional. Morris descreve a sua ficcional Hav com um intervalo de vinte anos entre uma estadia prolongada na colorida velha sociedade e uma visita ao enclave após um bem sucedido golpe de estado que coloca no poder uma teocracia cátara (leram bem) que arrasa o antigo para o substituir por efémeros e impessoais paradigmas de modernidade.

Hav lê-se como literatura de viagens ficcional, como um passeio Borgesiano a Üqbar se Borges escrevesse como Paul Theroux. Mas ao criar um elaborado e verosímil mundo ficcional que reflecte sobre as dicotomias do mundo real contemporâneo coloca-se no campo da melhor ficção científica. Não tem naves espaciais e raios da morte, mas tem a percepção de como as contracções históricas modelam os locais e as gentes. -

Hand on heart, I can honestly say I have never read a book quite like this. It reads like a travel memoir, but it's also a masterclass in worldbuilding and a love letter to place that doesn't exist but feels like it absolutely ought to. At times whimsical, it is rich in its observations of character and culture but also touching, surreal and deeply disquieting, especially in the second part (Hav of the Myrmidons) which reflects on abrupt social change.

I want to do justice to the book but I'm completely failing to articulate all the themes it touches on, like the persistence of myth, the vicissitudes of history and humanity's ability to endure in the face of both; I feel like I should have been taking notes as I was reading. In her epilogue Jan Morris describes Hav as an allegory, for the reader themselves to best decide what it all means. I'm certainly going to be chewing it over for quite some time to come. -

Jan Morris is an odd writer. Her prose is a strange combination of observant and precious, sharp and gushing, sometimes in the same paragraph. At times I think she's a mediocre writer with flashes of brilliance, and at other times, a superb writer afflicted by tone-deaf lapses of style. But I keep picking her up.

Last Letters from Hav, the first and longest section, is definitely better than the second. That novella is a love letter to travel and the messy, grubby exuberance of history; the second section, Hav of the Myrmidions is more a half-baked political allegory, tossed off without a lot of thought or depth. -

A travel book about a place which doesn't exist – or maybe it would be better to say, which only existed in Jan Morris' head. But then doesn't it now exist in the heads of the readers too? To be honest, I expected more of that sort of tricksiness, particularly given Hav's combination of European and Middle Eastern elements must surely have been an influence on the divided setting of China Mieville's The City & The City. But where that was making points about the way inhabitants of the same place can live totally separate lives from each other, and the vehicle for a thriller/mystery plot, this feels more like a daydream of a city which once played a key role in history but is now sinking into genteel irrelevance, something I'd want to call Mitteleuropan twilight except Hav clearly isn't in the middle, it's a peninsula somewhere at the bottom. The way it's gone back and forth between so many great powers from Sparta through Saladin to Venice and Imperial Russia, even down to having Europe's first Chinese settlement, made me think a little of Trieste, about which Morris also wrote, but that sense of being almost able to put your finger on where it ought to be is clearly deliberate. And of course, in a sense it's an artefact from that lost age of travel back before most places either had the same shops, or were nightmares. Back in 1985 it was still plausible that somewhere this hazy yet particular might exist in the cracks, that there might be survivors with scandalous stories of the War. And the survivors, it must be said, are for the most part wonderful character studies; in many respects this reminded me of an RPG sourcebook, all that lovely worldbuilding without a plot getting in the way, but they so seldom have quite such lively portraits of the pretenders, functionaries and less easily explicable folk who roam their invented realms. Which said, Over The Edge's Al Amarja is somewhere else I feel sure must have a little Hav in its genesis. Though on that axis Hav is undoubtedly closer to consensus reality, notwithstanding its snow raspberries, tailed hedgehogs and aphrodisiac salt.

But all of that is talking about 1985's Last Letters From Hav, which comprises only three-fifths of the book, the rest being taken up with Hav Of The Myrmidons, an account of a brief return in 2005. The earlier account ended with shots in the night, mysterious planes, the confused understanding of a coup which must have been all people on the ground could hope for back in the days before the internet. Twenty years later, Morris returns to find that unknowable event now safely archived as the Intervention, a key incident in the streamlined official history promoted by the new Holy Myrmidonic Republic. Among their other key texts, a few carefully selected and recontextualised passages from her own work – which has definitely not been banned as she'd heard, and how could she ever have thought such a thing? It just...isn't available. The mazy streets have been replaced with featureless new developments; some districts and familiar faces have risen, some have fallen, but all feels flattened. Still, even the dissidents say how you have to admit the place is richer and more organised now, as if that had ever been the point of places. With all the massive engineering projects and high-tech towers, the obvious real-world referent now is the UAE, although heavens know I recognise something similar whenever I go through Vauxhall. Likewise, while the carefully curated and impeccably teleological new history of Hav, and the attendant erasure of the messy reality, most obviously recalls the overweening national myths of a Russia or Turkmenistan, it's not as if Britain hasn't fallen for something horribly similar over the course of recent years. So in that sense Morris was regrettably prescient, even if the intellectuals' complaint about institutional lying feels like it can't possibly have foreseen just how bad things would get on that front, in what were once thought the great democracies as much as odd little city states. Part of me felt it unfair to blame all of this on, of all religions, the Cathars: surely the few times and places in which they attained temporal power in reality tended to see flowerings of art and culture? But aside from dodging the outrage of ghastly real and current religions, I suspect part of the idea there is to show how any religion can curdle over time; it's not as if Middle Eastern theocracies now bear much relation to Haroun al-Rashid's Baghdad either. A bigger problem is that it's just so much less fun to read about things going to shit, not to mention depressing to consider even imaginary cities being obliged to suffer the same degradation as real ones, a place which once played host to Edward Lear, Freud looking for eels' bollocks, and Lawrence meeting Ataturk, now reduced to visits from Princess Diana, "footballers' wives from Cheshire" - and nowadays doubtless Instagram influencers.

There is, though, one thing which holds true between both eras, and one which seems almost unthinkable now. Namely, this is a book by a trans writer about her own purported adventures and not once, in either the old-fashioned Hav of 1985 or the ideologically straitened peninsula of 2005, does anyone mention that, or have the least compunction about addressing her as 'Dirleddy'. Which I suppose you could read as one respect in which she allowed herself to craft her imaginary realm as utopian, though I suspect may just be a memento of how things were back before the world decided that was the issue about which it intended to have a massive bee in its bonnet for a while. -

I would rather read Morris on real places than imaginary ones. I know lots of people have enjoyed this, but I found it contrived and, therefore,not as funny as the author no doubt intended.

-

It's mind-blowing to think that the Mediterranean country of "Hav" exists only in the imagination of Jan Morris - so lifelike it feels, so real, so present, and so relevant. Being born in a Mediterranean country myself, I am doubly moved by the lost beauty of it, its tragedy (or tragicomedy), it's labyrinthian and composite nature (one civilization after another, Greeks, Arabs, Venetian Crusaders, Turks...; a maze of religions, a web of hybridized cultures). And finally, its obscene, nihilistic transformation in the wake of the capitalist takeover.

A journey to an imaginary country can take us closer to the truth than any realistic description. Morris' travel to Hav is proof of it. -

Hav is a story about globalization: What are the competing historical, cultural, political, and religious factors that all weave together to make up the fabric of an international city? And can anyone ever really get a firm grip on such a city's essence? There isn't much plot to the novel - it reads as a travel memoir, and there are only two characters worth mentioning - the author, our guide to Hav on two separate occasions, and Hav itself: an enigmatic, elusive, and somewhat shady character who is difficult to read.

-

A great, simple idea, executed well. A piece of travel writing about a place that doesn't exist, but is (mostly) completely plausible. Morris inserts Hav into history quite seamlessly, describing its fate through the Crusades, the Ottoman conquests, Russian rule, and the World Wars. She ends up with a place where a great many historical currents came together, resulting in a strange mix of influences in politics and culture (for instance, the Hav-Venetian school of painting). Then, in the sequel, she describes what is all too likely to be the ultimate fate of such mixture and ambiguity.

-

Despite irritating minor typos (not even corrected in the paperback edition) this is a wonderful book obsessing on dualities: ancient and modern, East and West, Light and Dark, land and sea, transparency and the occluded. The addition of Hav of the Myrmidons in 2006 to the 1985 Last Letters from Hav (presumably written as if to Morris' partner Elizabeth) adds to that sense of duality: as the earlier Letters ended a half year of somnolent unreality with the brutal suddenness of the Intervention, so does the mirroring second half of Hav end a six day tour of puzzling contradictions with a brusque departure.

Hav appears to be an independent state on a peninsula of Asia Minor, close enough to the known site of Troy to have been considered, Morris suggests, a contender; like Troy it has been coveted by other nation states, squabbled over by invading armies and temporarily ruled by transient empires. Hav itself is like an amalgam of all those liminal territories such as Hong Kong or Trieste that Morris herself has visited for her travelogues, and resonant with echoes of a few other polities such as Istanbul or Malta which have been at the crossroads of cultures. The Hav of the 1980s is a little quaint, a relic of its past histories but decaying in its inertia. While no less Kafkaesque post-9/11 Hav no longer retains its picture postcard attraction: all that has mostly been swept away by the sinister but shadowy forces behind the Intervention, leaving tourists in a modernist enclave and a population that is even more reticent to disclose what, if anything, is controlling Hav.

Morris' persona observes topography and demography alike with poetry and seeming ingenuousness, her descriptive and narrative skills making much of her imaginary land very real and believable. In the 1980s you mourn the imminent passing of an exotic state that has become anachronistic; in the new millennium you despair of the faceless machine that it has become. While Morris gets to meet many of her previous 1986 acquaintances in 2005, she is unable to get to the heart of what Hav has really become, though we can guess that the state has succumbed to the fate of many a nation turned totalitarian and subjected to a cultural revolution.

For anyone remotely interested in history and culture and in dialogue and interaction Morris' book has much to admire and celebrate. Aided by two outline maps separated by two decades, plus uncredited sketches presumably by Morris herself (the second group clearly being executed in seeming haste), she artlessly delineates the surviving architecture and hinterland of Hav City, blending the rich heritages of the Mediterranean and beyond into what at first seems an idealised backwater jewel surviving on past glories but which violently metamorphoses into another faceless metropolis of thrusting highrise structures, epitomised by the 2000-ft Myrmidonic Tower rivalling anything that Dubai can offer and twice as high as the Eiffel Tower or the London Shard.

I've already mentioned the notion of dualities that permeates Hav which is underlined by the Manichaean religion of the Cathar sect that emerges in the first part to rule the Holy Myrmidonic Republic in the second. The other notion that saturates the novel is the circular labyrinth, and though Morris never illustrates the exact form that this takes it is clear that it is not the simple unicursal or Cretan labyrinth that we have to imagine but the multicursal maze with numerous dead ends, where often as we seem to be approaching the centre the path veers off confusingly in another direction. And it is in the conjunction of duality and labryrinth that I think we have to find a key to what Hav is about.

Morris seems well aware of the contradictions that she encapsulates: gender-reassigned herself, she has veered from active service as a soldier in World War II to reportage as a travel-writer post-surgery. Her mother was English, and she was born in Somerset (perhaps the region referred to in a medieval Latin pun as 'the Summer Country'); her father was Welsh, however, and she certainly regards herself as Welsh, so it is noteworthy that she surmises that the name of Hav is derived from a pan-Celtic word meaning 'summer'. The puns don't just stop there. Morris is of course a common Welsh name, which may owe its popularity not just to medieval Norman influence but also ultimately to the Roman name Mauricius, from maurus meaning Moorish or dark-skinned, and which is thus a wonderfully ambivalent name.

A solution of sorts to the enigma that is Hav may come from the image of the pencil-thin Myrmidonic Tower that ends the novel. Standing moreorless centrally on the Lazaretto island, with its streets deliberately laid out in labyrinthine fashion, the tower looks down on a Borgesian pattern that most resembles the folds of a human brain. At the very close of the final chapter, as Morris flies from Hav for the last time as a persona non grata, she spies the giant letter M at the Tower's summit "shining there fainter and fainter, smaller and smaller," and she speculates on what the letter really stands for. Myrmidons, the legendary warriors of Achilles? Manichaean? Maze? "Or, could it possibly be ... 'M' for Me?" She can't really be clearer, I think: M is for Morris, the tourist who visits liminal places which exist only in her mind. What a privilege then that she agrees to share her experiences with us. -

“Hav” by Jan Morris is a brilliant, imaginative travel-fiction cum allegory about culture and change in the modern world. Morris, already a renowned historian and travel writer, creates the fictional city of Hav on the Eastern Mediterranean. This edition from the NY Review of Books consists of two novels: “Last Letters from Hav” (1985) and “Hav of the Myrmidons” (2005) that take place in Hav, a fictional city-state somewhere in the Mediterranean. The city is a polyglot mix of cultures, languages and sensibilities.

The first novel is more of a conventional travel narrative detailing Morris’ six months stay in Hav. Hav is a strange mixture of many influences, from Arabic, Greek, French, Italian, German, Russian. It even has a large Chinese community that came in the 1500s. The Crusaders were there and it is rumored that it is the last bastion of the Cathars. It may have been founded by the Greeks descended from Achilles or it may have been founded by ancient Celtic peoples who had wandered their way down to the Mediterranean. Hav is everywhere but nowhere. Unique yet instantly recognizable as a Levantine city with all its complexes and colors. Morris has a great eye for detail and puts these elements together into a combustible mix with much life but with something dark waiting in the shadows. One of the fun aspects of the first novel is that Morris sprinkles her narratives with quotes from famous visitors to Hav such as Marco Polo, Sigmund Freud, T.E. Laurence, etc… She describes the unique features of Hav society such as the Armenian who has played a trumpet voluntary on the ramparts of the crusader castle every morning, the dangerous but exciting Roof Race, the rare Snow Raspberries brought down by the Kretevs—the hill peoples—in the Spring, the incongruous Chinese pagoda on the coast, among many others, the large dog statue at the mouth of the harbor covered in graffiti of all the people who have come over the centuries. The first novel ends abruptly as Hav is invaded by foreign warships and the author flees over the mountains.

The second novel changes tone and Hav – now called the Myrmidonic Republic of Hav – has changed beyond recognition. After the “Intervention,” a Cathar theocracy takes control and Hav has now become a wealthy place. As Old Hav is an allegory of a twentieth century world, Myrmidonic Hav is a biting allegory of the twenty-first century world. Most of the old world is gone and what is left or been allowed to be preserved is commercialized. The Roof-Race is a now a sanitized global sports events hoping to get into the Olympics. The Chinese Pagoda has burnt to the ground but its ruins have been allowed by the new powers to remain as a reminder of the Old Hav. Snow Raspberries have now been genetically modified and produced in large quantities to be shipped all over the world. The graffiti on the dog statue has been removed. The trumpeter was killed during the Intervention but his memory has been preserved in a museum and the music has been preserved in a mechanical carillon given to Hav by the Chinese. At the center of the Republic is a large glad tower with a giant glowing ‘M’ with no discernible purpose.

The ancient symbol of Hav was a maze. And both Old and New Hav are mazes of different sorts. If the earlier Hav is a confusion of cultures and tones, the new Hav is a sanitized but opaque world where confusions are hidden behind attempts to create narrative. The most profound lesson for me came during the authors return to the Greek island of San Spyridon in the second novel. The Greeks here, far from being down-trodden like they were in the first novel, are buoyant and proud of their heritage. The new powers in Hav have crafted a new history of the city that emphasizes its Greek heritage. The New Hav has taken the various strands that informed the Old Hav and refashioned them into a simple, linear narrative that tries to reconcile irreconcilable parts of Hav’s identity and discarding the one’s that do not work. The Greeks are happy because they are now central to the simplified story. Their lives now have coherence but that coherence is a false creation of the present.

As you might be able to tell, I enjoyed this work greatly. I highly recommend it for its imagination, its beautiful details, and its trenchant allegorical rendering of the modern world. It is quite unlike anything you will read and I promise it will make you think long after you finish it. -

Jan Morris has travelled more than you or I ever will, and has likewise thought about traveling more deeply and written about traveling more prolifically than all but a few people alive today. In Hav, Morris distills that experience for the reader, giving us a guided tour through the city of her imagination, which amalgamates many of the locations- and more importantly, the experiences- that Morris has been through during her life.

Don't expect fully realized characters or much of a plot, this book is almost pure setting. Hav has a dash of a dozen different cultures mixed together, both ancient and contemporary, less a melting pot than a salad with every piece distinct despite having been squished together. Impressively, despite the fact that intellectually you know that such a city can't exist, Morris makes it feel real. During the first fictional trip to Hav (entitled Last Letters from Hav) the character Jan visits the many different realms contained in Hav, from Chinese settlements to ancient Greek monuments to troglodytes living in the mountains to a caliph in hiding to a middle eastern medina to a meeting of a secret society. In her epilogue Morris discusses this first part as creating a city where the tension stems from overlapping history, motivated by Morris' realization that despite her extensive experience traveling she very rarely feels like she gets to know the places she is visiting, or understands exactly what is happening. It's the traveller's curse, and in the first part of the book Morris makes such a feeling manifest by presenting us a city so complex it can probably never be understood even by natives, much less by tourists. The first part ends as tensions begin to rise in Hav, and a war of sorts approaches. Morris expertly captures the extra layer of uncertainty felt by a traveller during such times of crises, when you sense things are going wrong but you don't quite have a firm enough footing on the underlying culture and society to say for sure.

The second part of the book is perhaps even more impressive, as Morris returns to Hav after the rise of certain ill-defined powers in the wake of the military intervention that ended the first part. Though it's not always entirely clear who the powers at work are, what they are doing is made obvious: the new administration is transforming Hav from the old clutter of cultures and ideologies into a streamlined economic hub and tourist destination. The ancient and strange bits of character that used to make the city special are being sanded down, the history of the city being manipulated- "brainwashing really"- for the sake of commercialization. Yet though this shift seems terrible through the eyes of a tourist, this new Hav often seems better for the actual inhabitants of the city. Better houses, more jobs, greater safety (the narrator and another character lament that the famous roof-race of Hav has been revamped to make it safer and more uniform, stripping it of all it's charm. Of course it's important to remember that the charm brought on by the old race's danger regularly resulted in the deaths of the participants). These benefits come at the cost of much of Hav's former culture, and it's strongly suggested that the new government is totalitarian in nature, but the transformation is still not black-and-white.

Hav is a fascinating book, letting you experience the many questions that Morris has wrestled with throughout her travels without ever beating you over the head with them. Through the city of Hav you experience the feel of a dozen different cities, and experience a city changing from one of old but unique delights to one of generic manufactured cleanliness and prosperity. It's not for everyone, as the volume is essentially just the wanderings and wonderings of a travel writer through a fictional city sans plot or characters, and there's rarely any sense of urgency for you to turn the page, but if the idea of experiencing how a travel writer has seen the world and its evolution appeals to you then I highly recommend that you pick it up. -

Jan Morris is known for writing travel guides but perhaps her most famous one is a guide to a place that never really existed, that never existed outside of the mind of the reader and the author - Hav. This city state in the eastern Mediterranean has a long and varied history, with every great power interested, an eclectic society of Chinese, Arabic, British, Russian, and French influences.

Jan Morris' prose is sublimely beautiful, conjuring up such a realistic image of this place, it almost feels like she spent those six months strolling through Hav's narrow alleys and streets along to its harbour, to the House of the Chinese Master, and the international settlement which played host to international intrigue. Hav is alive on the page, the reader is transported to this magical place and longs to explore more - Morris offers just enough to tantalise and entice the reader, just like any good piece of travel writing.

The second part of the novel, Hav of the Myrmidons, sees Morris return to the former idyll several years later where she beholds a Hav totally transformed - long gone are the alleys and buildings of her former stay, replaced with a manicured resort for foreigners and a shimmering tower adorned with a letter M that looms large above the city. Hav has transformed itself, perhaps for the better; we and Morris are left with more questions than answers as she is whisked away before uncovering something beyond her knowledge.

Fiction of the highest quality transports its reader to a place born from the author's mind and made real. Morris here has written both a wonderful novel of vignettes in Hav, of its people, its culture, its history, and she has written a wonderful travelogue transporting her reader to a place so real that readers wanted to know how to apply for visas to Hav. Hav never was, but well could be, and that is its greatest success. -

A travel writer arrives at a tiny, once thriving Levantine city-state on the shores of the Mediterranean. She meets the people, sees the sights, evokes past and present through delicate description and historical anecdote, not always reliable, but even the stories are indicative of some aspect of the personality of the place. It is rich with culture and full of history, and yet it is an odd, elusive place, all surface, all smiles, hard to pin down, hard to truly understand. She will never understand the place. Her account is occasionally interrupted by odd little hints of things beneath the surface. They never coalesce into any real threat or danger or suspense, until the final pages, when with discreet and refined bewilderment she is ushered to the border, building to the incredible, subtle crescendo of the final line of Letters To Hav.

Hav, of course, is fictional, an invention by travel writer Jan Morris, who is also a character in this book. It is a 'hazy allegory,' but its true allegory is the difficulty of understanding a place. In Hav of The Myrmidons she returns, briefly, and discovers it transformed. It is more surface, louder, brighter, richer. And though she clearly prefers to withhold judgement and let people's own words speak for them, she cannot hide her frustration and even her anger that the changes have made the place even more hidden and ambiguous and secret.

A brilliant book, beautifully written, an astonishing piece of worldbuilding that hauntingly evokes modern dilemmas and confusions as much as it evokes a place. -

Hav is a fictional trading city located somewhere in the Mediterranean. It’s old. It has been around for centuries, if not millennia. It’s rumored to be on the site of ancient Greek Troy. It is ostensibly European, but has been conquered by Arabs, Turks, Russians, Venetians, British, and others. Each administration has left an indelible stamp on the city through buildings, urban planning, and population resulting in a labyrinthine conurbation with many distinct parts. It’s also a trading port. It’s most famous export is Hav salt, valued for its aphrodisiac qualities. Like other commercial hubs, it is populated by a varied mix of people that first arrive to do business, but end up staying, settling, and creating enclaves that add to the exotic richness of the place. The Hav Chinese built the most impressive structure, the tower of the Chinese Master. It boasts young Sigmund Freud as a one-time resident. Languidly paced, but hard to put down, Jan Morris’ Hav is a place I wish I could visit again.