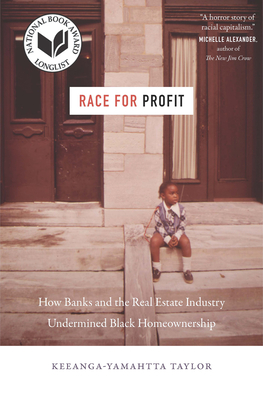

| Title | : | Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1469653664 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781469653662 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 368 |

| Publication | : | First published September 3, 2019 |

| Awards | : | National Book Award Nonfiction (2019), James A. Rawley Prize (2020), Ellis W. Hawley Prize (2020), Liberty Legacy Foundation Award (2020) |

Race for Profit uncovers how exploitative real estate practices continued well after housing discrimination was banned. The same racist structures and individuals remained intact after redlining's end, and close relationships between regulators and the industry created incentives to ignore improprieties. Meanwhile, new policies meant to encourage low-income homeownership created new methods to exploit Black homeowners. The federal government guaranteed urban mortgages in an attempt to overcome resistance to lending to Black buyers - as if unprofitability, rather than racism, was the cause of housing segregation. Bankers, investors, and real estate agents took advantage of the perverse incentives, targeting the Black women most likely to fail to keep up their home payments and slip into foreclosure, multiplying their profits. As a result, by the end of the 1970s, the nation's first programs to encourage Black homeownership ended with tens of thousands of foreclosures in Black communities across the country. The push to uplift Black homeownership had descended into a goldmine for realtors and mortgage lenders, and a ready-made cudgel for the champions of deregulation to wield against government intervention of any kind.

Narrating the story of a sea-change in housing policy and its dire impact on African Americans, Race for Profit reveals how the urban core was transformed into a new frontier of cynical extraction.

Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership Reviews

-

Insightfully breaks down how anti-Black racism has shaped U.S. housing policy, from the time of the New Deal into the present, diving deep into the impact and legacy of the HUD Act of 1968, passed by LBJ and administered by Nixon. Through the act the feds guaranteed urban mortgages, with few conditions, in order to incentivize private lending to low-income Black families. Eager to scam the government and Black communities, the real estate industry quickly pivoted from redlining to what Taylor calls predatory inclusion, in which exploitative mortgages on hard-to-maintain homes in segregated neighborhoods were freely lent to Black mothers, who were misinformed about their housing choices by brokers. When the act led to thousands of foreclosures and ruined lives, the Nixon admin cast all the blame on Black women and abandoned the project of guaranteeing fair and affordable housing, instead shifting to housing vouchers. Taylor succinctly covers so much history here, and foregrounds the voices of those targeted by the program, something sorely missing in many other books of this kind.

-

The private-public partnership has been a model long touted by politicians as a panacea for solving social problems without the bloat of government programs. But in Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor shows us how this model repeatedly failed black homeowners. She illuminated the low-income housing programs to encourage home ownership that enabled a new class of real estate professionals to profit off substandard housing, with the full backing of the federal government.

When housing policy shifted from building public housing to underwriting public private partnerships, she writes, “the HUD-FHA guarantee to pay lenders in full for the mortgage of any home in foreclosure transformed risk from a reason for exclusion into an incentive for inclusion.” She notes that by 1971, “federal subsidy programs were paying the real estate industry $1.4 billion a year and financing one in four new housing units produced.” In this way the shift in housing policy was a handout to the private sector while failing to regulate the activities of that sector, leading to scores of bad actors and bad outcomes for the people who fell prey to them.

Taylor brings us dozens of examples of these bad actors in practice. She writes of one study of Berkeley and Oakland, California, where “dilapidated homes were sold to low-income families for three and four times more than they were worth. The houses were “largely incapable of passing honest FHA inspection and certainly failed to meet minimum FHA standards.” In 1971, after a large outcry against the government’s failure to oversee these loans and guarantees, a study by HUD (overseen at the time by George Romney) found that eighty-eight percent of existing housing guaranteed by FHA and HUD had significant problems, while with 43 percent of new subsidized housing that had been build with federal handouts had serious defects.

The private / public model of affordable housing has at its heart a conflict of interest, and this plays out particularly along race and class lines. As the economist Paul Collier has succinctly put it, “people have two motives for buying a house. For most people it is a home; for some it is an asset.” There are fundamental mismatches in motivation between the public interest of providing housing for people and the private interest in maximizing profits from housing. As Taylor notes, the private (real estate) market tends to ignore the public call for safe and affordable housing, as the profit motive considers safe and affordable non-lucrative and thus a non-starter. But the rise of low-interest mortgage loans backed by the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) and Housing and Urban Development (HUD) created opportunities for those real estate speculators to profit from real estate sales that might otherwise be considered risky. The government diffused that risk, thus creating a moral hazard whereby real estate dealers were protected from the consequences of their actions, knowing they could be bailed out by the government.

Homeownership matters for so many reasons.

It has historically been the primary way wealth is accumulated in America. Exclusionary housing practices in communities of color have ensured that intergenerational wealth created by housing has accrued primarily to white families only. As Taylor shows through careful historical analysis and reams of data that private/public partnerships have only entrenched and intensified the battle for decent housing, while making the most vulnerable evermore vulnerable. This book is a serious work of scholarship showing how the actual results of political ideas are a far cry from the reality they produce. -

As much as everybody went nuts for Matthew Desmond's Evicted, and without trying to directly compare the two, this book might perhaps deserve as much or more cultural fanfare as Desmond's book received. Taking as a starting point the vaunted housing initiatives set in place under Johnson's administration, this book details the institutional and administrative failings that beset these programs, as well as the way in which the "public/private partnerships" so touted by The Great Society became little more than mechanisms for Real Estate and Banking interests to fleece both the federal government (with the tacit approval of HUD and FHA officials) and, more often than not, poor women of color.

Taylor does a phenomenal job of not merely mining the tendrils of redlining and the half-baked race "science" that underpinned basic assumptions around real estate values and the rules and regulations that fed directly into discriminatory practices that still exist today (sub-prime mortgages, anybody?) but of tracing the dots between redlining, federal policy and the coded and racialized language that has been used to denote who deserves or does not deserve public money, who uses or abuses public subsidies and public aid. She points her finger squarely at the way poor women of color were (and still are) demonized as "welfare queens," while at the same time 'upstanding men of business' absconded with millions of tax dollars for doing essentially nothing to alleviate segregation (indeed further cementing it) and by conning people who just wanted safe, adequate housing near job opportunities into incurring debt.

While Desmond's book discusses the need for more housing assistance, this book a makes more substantive case against the racist rot of our mindset towards housing from the outset, and the dire need for substantive changes towards finally achieving safe, affordable and integrated housing across this completely fucked up, racist-ass country. -

There is some irony that on the release day of Barack Obama's much feted memoir I finished Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor's history of race and housing in the 1960s and 1970s. After all one of the most powerful criticisms of the Obama presidency was his administration's handling of the housing crisis, choosing to bailout the lenders largely responsible for the financial collapse while offering nothing to borrowers facing foreclosure of their mortgages. This facilitated the greatest destruction of wealth among African-Americans, a demographic heavily reliant on home ownership as a savings vehicle.

Taylor gives us a meticulously researched and persuasive account of how federal housing policy has largely failed African-Americans. Situating her account between the Johnson and Nixon administrations, Taylor argues that even the more liberal and aggressive attempts to reshape housing in the United States under Johnson failed to make significant strides in achieving equal access and opportunity for Black home ownership, beholden and influenced by private real estate interests whose drive for profit made them unwilling to break with racial norms to desegregate housing. The early years of the Nixon administration showed some promise under Housing Secretary George Romney to continue at least in principle aggressive attempts to desegregate housing, but reelection aspirations quickly pushed Nixon to break from these efforts to appease his base among white homeowners in the suburbs.

Taylor has produced an incredibly important history of the politics that destroyed the liberal attempts to end housing segregation and ushered in neoliberal hegemony that handed the market unfettered power to manage access to quality housing in the United States. While most lavish Obama today as he releases Promised Land, its important to not forget how his presidency continued a long line of administrations failing to address inequality in a realm so essential to American identity, home ownership -

I've been researching this topic for a book proposal I'm working on. I'd been piecing together the story myself when I came upon this book. Thank you Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor for this astoundingly well-researched book. It's a long and complicated story and I now feel like I have a handle on it.

-

Race for Profit is a deeply researched, impeccably argued study of the conception, implementation, and consequences of HUD-FHA's low income housing programs in the late 60s and early 70s. Previously, redlining by the government and the financial sector meant that Black people and Black neighborhoods were--legally--perceived as risky investments due to race. Thus Blacks were overwhelmingly excluded from the rising postwar prosperity enjoyed by whites, who were extended generous FHA loans to buy houses in the suburbs whose value was precisely tied to their location in racially homogenous white neighborhoods.

Federal redlining officially ended in 1968, but racialized residential segregation and wealth disparity did not. That year, in response to residential segregation and housing shortages, Lyndon Johnson signed the Fair Housing and HUD (Housing and Urban Development) Acts into law, which centralized federal housing policy under one department, prohibited explicit racial discrimination in the housing industry, and created a public-private partnership between the government and mortgage banks to incentivize investment and encourage homeownership in black communities. Crucially, the central mechanism created to achieve these goals was heavy government subsidy of private mortgage loans: if a bank offered a standard loan at 8% interest and $1,000 down payment, HUD would pay the lender 7% of the interest and $750 of the down payment, greatly easing the borrower’s financial burden. In addition, the entire loan was guaranteed by HUD, meaning the mortgage banker got paid the full amount of the loan, even if the borrower defaulted. Because it was conceived as a public-private partnership (for reasons that have to do in large part with the ballooning costs of the Vietnam War) HUD’s low-income housing program absorbed the deeply ingrained racial prejudice of the housing industry, a prejudice so integral that it structured the entire housing market, and touched every element of the home-buying process, from mortgage underwriting criteria, to appraisal, to zoning, and more. By completely removing the risk associated with lending to Blacks without remedying the racism of the housing industry, the new program created a perverse incentive for banks to generate as many new loans as possible without ensuring--and often willfully overlooking--their viability (an incentive that was supercharged by the introduction of a new financial instrument called a “mortgage-backed security,” hmmmm). In fact, under this regime, mortgage banks were especially incentivized to loan to buyers who they knew could not afford the terms of the loan, because when the house went into foreclosure, they could buy it again at a low price and start the process anew, getting paid in full by HUD no matter what. These incentives, in combination with disastrously inadequate oversight, meant that poor Blacks in urban neighborhoods with old housing stock were sold homes they couldn’t afford, at inflated prices set by corrupt appraisers, and given no material support should they almost inevitably fall behind on mortgage payments and maintenance costs, leading in most cases to quick eviction from homes they were promised were the ticket to the American Dream. Though the exclusionary race discrimination policy of redlining had ended, HUD’s federal mortgage insurance scheme created a new regime of wealth extraction in Black neighborhoods through a pernicious “predatory inclusion.”

Though Taylor makes clear that it was the combination of racism and profit-seeking in the housing industry that caused HUD-FHA’s low-income mortgage insurance scheme to fail, she also documents the program’s mismanagement under Richard Nixon and his HUD secretary George Romney. Nixon sought to cut back the burgeoning administrative state created to oversee LBJ’s Great Society initiatives. This desire dovetailed with his “southern strategy” of dogwhistle racism to consolidate his white suburban political base. With these goals in mind, Nixon took two measures that effectively doomed HUD’s fair housing initiatives to failure. First, he announced that the federal government would not take punitive measures against white suburban neighborhoods that resisted the construction of low-income housing, even though withholding federal money is the central enforcement mechanism of 20th century American civil rights law. Then, Nixon handed down severe budget cuts to HUD, crippling its ability to properly administer such a large, regulation-intensive program. These two actions greatly exacerbated the existing structural problems involved with the mortgage insurance scheme, nigh-guaranteeing the failures described above. Nixon then blamed this failure on the Black homeowners themselves, taking it as evidence of a deficit of character among Black citizens rather than the result of the racism, profit-seeking, and mismanagement of government and private industry.

The HUD act’s low-income housing scheme fell as part of the wider turn to neoliberalism, which Taylor helpfully reminds us was as much a white backlash against the civil rights provisions of the 1960s as it was a corporate backlash to the stagflation and unemployment crises of the 70s. But its failures were not inevitable. Taylor’s analysis suggests that the program would have been more viable if it did not rely on incentivizing private investment, and if the government took civil rights enforcement seriously (If these seem like unlikely counterfactuals, it’s because American capitalism is deeply racist). But because it was a public-private partnership under the aegis of a large federal agency, and because the government did not take civil rights enforcement seriously, Nixon could paint the mortgage insurance plan as a wasteful government handout to undeserving racial minorities, and then use this as evidence that the welfare state needed to be dramatically curtailed, rather than reinforced. These days, we face a cascading series of crises--climate change, extreme wealth inequality, health care, drug-resistant microbes, and more--that call for massive public investment. Taylor’s book should remind us that there are better and worse ways to structure this investment. First, do not structure the investment around the profit-seeking behavior of private actors. Instead, use social welfare as the basis of taxpayer-funded government investment. Second, do not apportion this investment according to racial or other prejudice. Instead, make sure the programs are well-funded and use existing civil rights law to rigorously safeguard against uneven apportionment. It’s no coincidence that these steps cut directly against the principles of neoliberal governance. They are essential qualities for any program that aims to tackle one of the slow-rolling catastrophes listed above.

---

I keep trying to add some personal reflections on reading the book at the end of this review, but I find that nothing I write adds anything substantial to my attempt at a description of Taylor’s argument. It’s an argument so powerful, and so well-supported by original research, that all I can say is that if you are interested in mid-century American politics, structural racism, political economy, housing, or (broadly speaking) justice, you are obligated to find a copy of this book and read it as carefully as possible. The style may be a bit academic (it is adapted from a dissertation), but this is in service of precision, not obfuscation. -

Difficult to read - not in the style but in the topic. Depressing and frustrating, and clear about how systemic racism has affected the real estate community.

As it is a well-done master's thesis, ultimately, it is three stars as a book, but five in the information, which averages to the four stars. -

“Race for Profit” offers a detailed look into the ways federal, state, and local housing policies have functioned to deprive POC of home ownership. For example, HUD and FHA policy has been undermined by banks and the real estate industry so as to keep POC from moving into predominately white suburbs, even after the government officially ended redlining.

The author examines closely George Romney’s role as HUD director during the Nixon administration. I’ve read books and articles about housing, including “Evicted,” and consider myself a fairly informed person, but nothing prepared me for the extent of what I learned listening to this audiobook.

Topics Predatory inclusion: expensive and unequal lending terms

-Best practices in real estate created inequity.

-racial discrimination seen as good business

-realtors say POC bring down property values

-Frederick Babcock created real estate value appraisals. These contributed to low value of housing in black urban areas.

-real estate industry required segregation to preserve value and private industry interests.

-normative whiteness

-racialized narratives of family

-Nixon: guild the ghetto

-subprime marked black neighborhoods

-zombie properties

-coded speech such as “urban crisis”

-1973 Nixon moratorium on subsidies for housing

-Ch 1:

-rats as symbol

-2-year old infant eaten by rats

-hostility of FHA to black buyers

-Shelly v Kramer on restrictive covenants

-1949 less than 2% of FHA loans to black people

-urban renewal destroyed affordable housing

-VHMCP failure in 50s

-FHA refused to act against discrimination

-free market hypocrisy

-residential segregation

-block busting: buy from whites to sell to blacks

Economic racism

-segrenomics

These are just a few of the revelatory moments in this important book. Teachers using any text that addresses housing, such as “A Raisin in the Sun” will enrich their units w/ passages from “Race for Profit.” -

Excellent Study African American Housing Policy

This is great account of the history of federal help for housing of African Americans since WWII. It covers a lot of policies and laws and provides a fascinating account. When government makes a commitment and economic problems happen, social programs are the first to go and the last to come back. -

one of the clearest case studies for systemic racism that i’ve come across.

-

This was a very well-written book; it was fairly easy to read despite the depth of knowledge and research it contained. However, it was still a bit easy to get lost, in that the chapters were semi-chronological but often overlapped in different time spaces.

-

My partner and I read this as a mini-book club, with informal discussions after finishing each chapter. It was an interesting experience, given my background as a financial regulator and her background in critical race theory and education.

I think I was right in Professor Taylor's target audience, as someone quite familiar with the history of redlining but not as familiar with the transition of federal housing policy to a public-private collaboration approach in the 1970s (where it remains today). "Enjoyed" is probably not quite the right word, given the nature of the policy shifts covered, but I did learn a lot from this book. Some highlights:

-The FHA turned to the private sector to scale up its mortgage lending activity, but never committed the resources (or had the political will) to adequately monitor and enforce compliance with fair lending laws designed to prevent racist behaviors. Given the government's continued reliance on the private sector as a force multiplier today (e.g. PPP lending), this is an important precedent to be aware of--and indeed racial disparities in PPP lending have already been raised by several groups.

-George Romney used a lot of rhetoric of integration and antiracism (and indeed, he came across as pretty admirable to me in the early chapters of this book), but ran an organization in the FHA that remained racist in its treatment of its own employees. Ultimately his commitment to integration in the FHA's activity as well is shown to be weak as well. Today, we're seeing a lot of organizations publicly espousing antiracist views, but also seeing employees come forward to denounce white supremacist internal behaviors and structures.

-I appreciated Prof. Taylor's breakdown of "the real estate industry" as a non-monolithic entity. She shows how the interests of homebuilders often conflicted with the interests of mortgage brokers (most clearly, on the relative importance of new construction vs. refurbishing of existing properties). It's certainly a powerful industry, but effective politicians on either side may be able to exploit internal differences.

-The cult of homeownership takes on a life of its own. Prof. Taylor shows how the FHA programs often pushed Black people into buying houses even when they preferred to rent. The numerical goals of the programs superseded what should have been the ultimate motivation of the programs, which is to provide people with better and more integrated housing situations.

-The 70s see the beginning of suburban municipalities using zoning law to prevent the construction of affordable housing and therefore of integrated neighborhoods. This practice is still alive and well; in my own state, the Connecticut Mirror has provided excellent coverage of it. Withholding federal funds from municipalities is shown to be an effective deterrent, but one that takes a lot of political will to apply.

-Much like with attempts to integrate schools through busing, the most affluent White communities are basically unaffected, and all of the integration efforts are targeted at working class White communities. The result, even if effective, is only partial integration, and more commonly the result is failure. The communities with the most resources to support lower income families are not called upon to do anything, and cynical (probably wealthy) politicians can use integration to stoke racist resentment in the White working class.

Professor Taylor shows how the turn to the private sector in federal housing policy was driven in part by the federal budget pressures caused by spending on the Vietnam War. As I remarked to my partner, one of my takeaways from the book is that racial discrimination and inequalities are so entrenched that it takes a war level of effort (resources, planning, strategy, tactics) to address them. We see the National Guard being called in to enforce racial integration of schools in the South in the early years, but political will dying out later with the project of integration unfinished. Johnson couldn't summon a war level of effort to integrate housing while fighting a shooting war overseas. Will our nation be able to summon a war level of effort to address racial disparities in the 21st century? -

Summary: This was a fascinating, infuriating, and important read, but it could also be dry and repetitive at times.

I'm so glad I got around to doing an end of month round-up and realized I'd not yet reviewed this book, because I'm excited to tell you about it. Like many of the National Book Award nominees, this book deals with a heavier topic. It covers the many ways that government housing subsidies in the 1960s and 1970s disadvantaged black families. Several major problems with the program allowed race-dependent outcomes. In particular, it seems that none of the administrations that ran the program were willing to enforce civil rights law or provide adequate oversight of housing quality. This allowed the real estate industry to continue racist practices while receiving government funding. Add to this some perverse incentives that meant banks could make more money on mortgages if tenants were evicted and you have a recipe for disaster.

As you might expect, this book covers history everyone should be aware of, but it will make you incredibly angry. I'd already read about some of the racist real estate practices described in this book, but their relationship to government programs were new and horrifying to me. I learned a lot from reading this. It was clearly well-researched and gave a thorough history of these government programs. Like many NBA nominees, it made me want to read many of it sources.

If I'm honest though, I could have done with a less thorough history! The broad outlines of the government programs were almost as interesting as they were appalling. The personal stories that were included were also engaging and brought home the devastating human cost of these programs. The details of who was running the programs and the political context weren't as interesting or important to me. Nevertheless, I really would recommend this to pretty much anyone in the US as an important part of the history of our country. I'd just replace it with something even more accessible if that was an option!

This review was originally posted on Doing Dewey -

Powerful, harrowing, clinical. Taylor does the dirty work so you don't have to and spells out her hypothesis in plain, no-nonsense language. At times it's like stepping into the ring with a prize-fighter with the facts hitting you like uppercuts and haymakers. But once you make it through you'll be a little wiser, hopefully a little more compassionate and have a greater understanding of the obstacles that Black people have had to go through just to live in this country. And maybe, just maybe, you'll be galvanized to help fix it.

-

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor novel Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership, is another example of how hard it is to be Black. The stunts the government has pulled in the housing industry….ugh! I don’t even know where to begin here.

Throughout this book Yamahtta Taylor highlights on the low-income housing programs (HUD) that encouraged “Black homeownership” but, ultimately was a set up from the start. The purpose of the Federal Housing Administration is to back mortgages arranged through a government funded program that would pay off loans if buyers defaulted on their payment. With this program, Black renters from poor areas had an opportunity to become homeowners. Yes! Great news, right?!

Wrong! Crumbling structures, rat infested homes, all these conditions opened the doors for homeownership fraud.

At the end of the day real estate brokers and mortgage bankers valued black owners because, they were poor, desperate and would likely fall behind on their payments. And you know what that means, banks would profit from being repaid for inflated mortgages, and profit again when the foreclosed property was resold to another poor family that qualified for a government-guaranteed mortgage.

cha-ching!

Yamahtta Taylor did some extensive research and her findings are shocking. This book is dense, but soooo informative. This is a must-read.

Many thanks to University of North Carolina Press for gifting me this copy. -

If you’ve read The Color of Law, this book should be next on your list. This book picks up where the other left off detailing how discrimination continued after the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 and telling the story of the creation of HUD, its many issues, its gutting, and how the government was able to shift blame from itself onto the black poor it claimed to want to help.

-

A book about federal housing policy published by a university press wouldn't be getting this much attention if we weren't in our present situation, but that doesn't mean it doesn't deserve your appreciation. Race for Profit is not an overview of how the federal government, banks, the real estate industry, etc. have conspired to fuck over African-Americans post-Reconstruction but it does pop in the stories of redlining, the Great Migration, and the disaster of massive public housing projects on occasion, if you're unfamiliar with those parts of the story. This book primarily focuses on the unmitigated disaster wrought upon Black families between 1968 and 1973, when a more conservative government headed by Nixon ended federal support for public housing and used the combined powers of HUD and the FHA, headed by Mitten's dad George Romney, to encourage home ownership in Black neighborhoods by offering mortgages to poor families. Romney made some weak attempts to integrate working class suburbs, but that didn't happen. Meanwhile, enticing, coercing, or forcing people searching for rental housing into home ownership became a nightmare way for realtors and lenders to make quick money by "selling" distressed properties, receiving reimbursement from the federal government for their overhead, and getting paid again when the properties were foreclosed on. Dozens of people were eventually indicted but, despite all the appalling stories where the lenders and realtors were clearly at fault, the blame was inevitably placed on poor Blacks for living in places they couldn't move out of. Tragic, worth reading, good audio narration.

-

2020 has been a fucking awful year, but I resisted shying away from books that presented hard, depressing, anger-inducing, honest assessments of White Supremacist America.

This is another of those books. Fucking hell White Supremacist America had/has quite the insidious and horrifying racist real estate and banking industries. No surprise here, since the "land of the free..." was built, sustained and expanded through the legalized/codified enslavement of Black People for hundreds of years, then their subsequent post-slavery slavery that continues to the present day.

This book is overwhelmingly forthright in proving that White Supremacist American Government, at every level, worked openly and obviously to exclude Black People from home ownership at every possible place in the chain of home acquisition. And still does.

There is a lot to absorb here, but readers dedicated to learning how fucking racist America is will be rewarded, sadly, with plenty of examples. Simply put, White Supremacist America continues to blame Black People for their plight, refusing in any way to acknowledge that a nation that would enslave another human being has created the problem while refusing to accept the horrifying results.

None of the problems of the USofA with regards to racism will be mended until reparations are paid. Black People started with way less than zero in America, so there is simply never going to be any "catching up", regardless of any future developments. Until White Supremacist America admits its terrible past wrongs and makes them right Black People will be running to stand still. At best.

An essential read, especially for those who think the symptom of White Supremacist America's racism - Black People's economic deficit relative to White People - is actually a fact. Yes, that means the very people that should read this book, White Supremacists - probably won't. Fuck them, I say. -

There is so much more to the history of Blacks and homeownership in the US than redlining and restrictive covenants. As with most policies in the US, centuries of exclusion are very difficult to recover from for the most marginalized and minoritized populations.

Mitt's dad George Romney plays a very large role in the book, during his time as the head man at HUD.

Recommended for history geeks, policy wonks, and housing scholars. Natives of Baltimore, Detroit, St. Louis, and Chicago will probably recognize a lot of the tales and references. -

I have no idea how I used to read academic books for fun, and so quickly, but that’s not my brain anymore. Some months I read it, some months I didn’t, but I made it through.

A doozy, but I learned a lot. Very important for folks interested in American neoliberalism. My props to the research assistants. -

It can get pretty dry at times but it is a pretty dense topic. Lots of details about the history that I might otherwise have been familiar with only anecdotally or on the surface. Lots of detail about federal efforts around HUD in the 60s & 70s, very much had me thinking about the impact and similarities a half-century later

-

I’ve never been one to fully grasp the intricacies of U.S. policies, but Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor writes about them with historical, social and political perspective. This could have been a dry reading experience or an emotional one, neither of which appeal to me, but the author did her research so well that the experience was rich, informative, frustrating and enlightening. And there are moments of humor, too. Not “feel good” humor, but the “Oh my God, seriously?” humor. (See the Good Housekeeping cartoon for an example.)

I recommend buying a copy so you can underline and take notes as you read. This book comes with an excellent bibliography and index, too. I look forward to reading more work from this author. -

Finally finished it. The information was frequently repeated so the writing style wasn’t my favorite. But interesting history of oppression and swindling of the poor via the real estate industry.

-

Well researched, scrupulously edited, and such a convincing narrative. KYT is so good. Definitely denser non fiction than I can normally digest, maybe a mistake to try this when so burnt out from work these days, but once I got half way through it was smoother.

Knowing KYT is a leftist, I was surprised at the lack of inclusion of the perspective of radical orgs most of the time. For ex, a policy will be described, then include what the perspective was from congresspeople, HUD, NAACP people, a developer, etc, and I get the impression she’s going to demonstrate why these people were wrong about public private partnerships ensuring equity and justice, but I feel like the BPP and others knew this at the time. For a book about the fed and the real estate industry failing the people, with a ton of primary source research and quotes, I would have liked to have some more perspective from the people at the time. But there are a lot of legit reason I can think of for the focus on mainstream stakeholders, and maybe it’s also because she has another book more about that specifically (rats, riots, revolution?). In this one she mostly mentions the 60s unrest as part of the pressure leading to the fair housing act. -

The belief that systemic racism is non-existent in contemporary America hinges on the fact that there are no longer any official laws on the books with punitive outcomes based on skin color, race isn't even mentioned. But looking at the specific moment in history when our laws became "color-blind" reveals how systemic racism can remain intentional policy without having to formally acknowledge race at all.

That inequality between black and white American's exist is an immutable fact. No pundit, no matter the ideological stripe, can deny this. The view on the left that I've always thought most convincing is that systemic racism - racism embedded into various systems and institutions rather than the racism of personal interaction - is largely the cause of these inequalities.

Systemic racism can be seen in current systems; black Americans are disproportionately targeted in traffic stops which is a variable in why they are disproportionately incarcerated, which is a variable of racial inequality. It can also be seen in systems in the past; the federal government's policy of redlining being used to deny black Americans access to quality housing in the suburbs being coupled with discrimination in education and the employment sector causing the wealth and opportunities garnered from homeownership to be severely stunted or non-existent, which is also a variable for current inequalities.

The arguments against the view that systemic racism can be used to explain racial inequalities most often emanate from the right (but not always) and usually take two forms with one core premise. The first form is that systemic racism does not currently exist because there are no laws on the books that specifically delineate skin color. The second is that, while systemic racism was existent in the past (only real sickos deny the existence of Jim Crow) it has little to no bearing on current inequalities because....there are no laws on the books that delineate skin color anymore.

To demonstrate we're going to use prominent right-wing commentator Ben Shapiro taking on a video about systemic racism from ActTV. Shapiro is one of only a few commentators I've ever seen to attempt to take on redlining and systemic racism in such an accessible way. As we'll see, his argument against the impacts of historic redlining and higher-ed admission discrimination hinges largely on the fact that those two policies are now illegal (3:34):

The move conservatives like to pull from here is to suggest that any current examples of racism are actually other factors not having to do with race at all. Here Shapiro rejects the possibility of modern redlining because the example of redlining cited in the video wasn't using race as a factor, it was using "liabilities, employment history, credit history, and other variables" (7:50):

Even the suggestion that systemic racism from times past might play a factor in current inequalities is rejected by Shapiro because he posits it's impossible to know how much this could be true given that our modern policies on lending and school funding are race-blind; they don't mention race (14:17):

This Race Blind Theory becomes the favored rhetorical move of the racism-skeptical because it evokes a simple truth to reject two powerful arguments. You saw Shapiro use this with housing in the above clips, but if you can stomach the video, he will use this same move for mass incarceration, school funding, and unemployment. There are, objectively, no laws, rules, or policies that specifically mention race, once this premise is accepted you have no choice but to acknowledge that inequalities stemming from these systems are from "other variables", as Shapiro does.

Fortunately, we don't have to accept the premise of Race Blind Theory. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor is a professor of African American Studies at Princeton University and has been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize for History. She is also the best living writer who tackles Race Blind Theory. Her book From Black Lives Matter to Black Liberation was a look at why mass incarceration and the legal system treats black Americans unfairly despite our criminal laws having no mention of race. Taylor's most recent undertaking is "Race for Profit", where she takes a specific look at the moment in history the racist federal policy of redlining was made illegal. Not only does KYT demonstrate that once redlining was made illegal the ramifications of this systemic racism didn't magically go away as Shapiro asserts, but she also shows that the ramifications were used to institute a racist system under cover of being race-blind.

The thrust of KYT's argument in Race for Profit is that once racial segregation was created and brutally enforced through a combination of state policy and community violence, simply making the policy go away wasn't going to get rid of the segregation. In fact, as KYT goes on to show, there were many private actors in real estate and finance that profited from the existence of segregation. As she notes in the introduction:

"Racial real estate practices, then, represented the political economy generated out of residential segregation. The real estate industry wielded the magical ability to transform race into profit within the racially bifurcated housing market. The sustenance and spatial integrity of residential segregation, along with its apparent imperviousness to civil right rules and regulations, stemmed from its profitability in white as well as African American communities - even as dramatically different outcomes were produced. In the strange mathematics of racial real estate, Black people paid more for the inferior condition of their housing. They referred to this costly differential as a 'race tax'. Real estate operatives confined each group to its own section of a single housing market to preserve the allure of exclusivity for whites while satisfying the demand for housing for African Americans. This was evidence not of a dual housing market but of a single American housing market that tied race to risk, linking both to the rise and fall of property values and generating proits that grew into the sinew binding it all together"

In other words, redlining continued after it was made formally illegal, but it was under the guise of being "race-blind" and even more dastardly, in the name of housing equality.

The preservation of segregated housing was still deeply intentional and it was actually the decision to make the language of housing policy at the time race-neutral that demonstrates why. The new, purportedly fair, housing policy was not about "redress, restitution, or repair", if it had been it would have specifically tried to address the harm that redlining caused, the effects it still had. "Instead, by ignoring race, new practices that were intended to facilitate inclusion reinforced existing patterns of inequality and discrimination". KYT points out that African American neighborhoods were given a racially neutral descriptor like "subprime", which served the purpose of making them uniquely distinguishable from white neighborhoods (keep Shapiro's "other variables" comment in mind here) without any mention of race. Of course, these neighborhoods weren't prime, they had been segregated and brutalized for decades, but a race-blind law won't recognize this because doing so would have to acknowledge race as a determinant in the value of these homes.

This can be seen in a variety of housing programs and policies at the time. When the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was removing racist language from underwriting manuals and orders of operations and promising to expand homeownership to African Americans, it was, at the same time, crafting a new language to institute a "Separate but Equal" policy in housing lending. Even where middle-income black families did receive loans for housing in the suburbs after the legal abolition of redlining, Race for Profit is full of stories about the violence these families faced from the existing white communities. Fire bombings, rioting, pipe bombs, and segregation policy passed at the municipal level in the name of protecting property values (such policy was held to be lawful in courts around the country). Even though race was absent from the letter of the law, much of white America still practiced segregation by any means necessary well after 1968. It's ludicrous to pretend this wouldn't have ramifications only 50 years later.

It's also true that just because something is illegal does not mean it doesn't still happen. Laws banning discrimination, like laws banning anything, are only so good as the body of government tasked with enforcing them. KYT points to the number of mortgage lending organizations that "simply ignor[ed] federal rules against housing discrimination". And the ones that adhered to the anti-discrimination rules could get around them by using, as Ben Shapiro would call them, "other variables"; "the lenders could limit loans based on their location and the requirements that the homes or buildings to be purchased had to remain in the 'city core'". This meant that all of the loans these organizations had to cut to black Americans could easily be given exclusively for housing in predominately black areas without ever having to evoke the racial identity of their borrowers or the locations they were marketing them to.

Conservatives like Shapiro, after claiming wildly that the illegality of systemic racism effectively ends it, will then move to say that racial disparity exists because of personal choices. As KYT puts it, it is a belief that "the systems and institutions of the country [are] strong enough to bestow the political, economic, and social riches of American society onto all who [are] willing to work hard and commit themselves to a better future". While the systems and institutions offer a colorblind market where economic fitness reigns the ultimate indicator for access to those choices, the problem is that systemic racism has already impacted that economic fitness, and so what is then created is a cycle of racism without the acknowledgment of race.

And the cycle continues with real ramifications. If systemic racism continued after it was made illegal, when did it stop? The answer is never. To quote KYT at length:

"The quality of life in US society depends on the personal accumulation of wealth, and homeownership is the single largest investment that most families make to accrue this wealth. But when the housing market is fully formed by racial discrimination, there is deep, abiding inequality. There has not been an instance in the last 100 years when the housing market has operated fairly, without racial discrimination. From racial zoning to restricted convents to LICS to FHA-backed mortgages to the subprime mortgage loan, the US housing industry has sought to exploit and financially benefit from the public perceptions of racial difference. This has meant that even when no discernable discrimination is detected, the fact that black communities and neighborhoods are perceived as inferior means that African Americans must rely on inherently devalued 'assets' for maintenance of their quality of life. This has created a permanent disadvantage. And when homeownership is promoted as a key to economic freedom and advancement, this economic inequality is reinforced, legitimized, and ultimately accepted"

A collaboration between Reveal and the Center for Investigative Studies showed that there were was still, in 2019, discrimination in lending happening in Michigan among other areas. Even now that lending eligibility is largely determined by algorithms, mathematical equations with no perceived threat of implicit human biases, the host of "other variables" that have been cultivated by years of legal and compounding, below-board discrimination are still impacting disparity in homeownership and wealth between black and white Americans. This is the definition of systemic racism. -

Dense but well worth the read. Learned a ton about a subject that doesnt get much attention. Definitely recommend.