| Title | : | Louise in Love |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0802137601 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780802137609 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 81 |

| Publication | : | First published December 14, 2000 |

Louise in Love Reviews

-

. . . Let go the leash

of the bad dogs that are dragging you this way and that.

And indeed, the hand could unclasp (Look at that!).

The leash fell at her feet.

Louise in Love was the twentieth book in my October poetry project. This was a reread; I had given it only two stars the first time around, nearly 10 years ago. Initially, I thought things might go the same way this time. The problem, I think, is that the description on the back cover refers to this as a "verse-novel," so I spent a while waiting for a plot to cohere. But the thing is, this isn't really a "verse-novel," it's a collection of poems, some of which are related to others. Not the same thing! Once I stopped waiting for this to behave like a novel, I started loving all the imagery in this collection. The language really is masterful, and beautiful. I plan to read this again sometime and to try to remember from the start not to be looking for a plot but to just let things unfold as they will. -

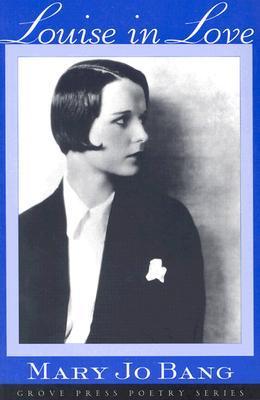

The inspiration for Mary Jo Bang’s magical verse novel, Louise in Love, is the life of early film star, Louise Brooks (1906 -1985). Brooks (“Lulu”) was famous for her black helmet of hair and a film presence that blended innocence with a charged-eroticism. She would develop, despite the relative brevity of her film career, into one of Hollywood’s earliest, and best, femme fatales.

Bang’s collection loosely covers the adult arc of Brooks’s life, touching on the actress’ film career, her loves, and her later battle with severe arthritis. But Louise in Love also accomplishes something more than reimagining the life of a film star, it is a homage to the great modernist fictions of the 1920s. At a late point in the story, Louise enters a room carrying a copy of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. This sly literary wink by Bang seems appropriate, since the ghost of Woolf, that most poetic of modernist prose writers, has hovered since the first page.

In the collection’s first poem, “Eclipsed,” Louise is an old woman, apparently dying. Outside, the sound of birds and a gentle rain has stirred old memories. It is these memories, poetically imagined, that will rise above the old woman’s worries and fears as they have existed for some time in the grim “novelese” of the present day:

How cold she was

as the cloud covered the cuckoo-land,

birds batting at the tree fringe. Fitful caprice.

Foolish, yes, they were, those birds, but clever too.

A nostrum of patterning rain has fallen

beforehand ceding the hibiscus buds bundled

and in disarray. In the news p. Nostradamic foretelling

of retinal damage written in novelese.

However, convulsions return (a heart attack?) and Louise is faced with imminent death. For the old woman, a reconciliation must be effected, or at least an accommodation with regret, as these memories, wanted and unwanted, move to their places upon the stage:

Louise placed the next-to-night glasses on the table.

It is, she said, so over. But it wasn’t.

Specters they would be

rooted eighty-two years in the same spot waiting

for another and then an offhand remark and one by one

(which is the way day death takes us, he said)

they took their shadows

and went out of the garden and into the house.

There is, of course, nothing quite so static as a stage in Louise in Love. It all exists within the shifting kaleidoscope of Louise’s head. Bang does provide a Dramatis Personae, but the actors here are all phantoms -- glimpses, sensations, fragments of conversations, that make up less than whole individuals. Ham (Hamilton Gordon III), Louise’s lover, is perhaps the most realized character. He has the cocky ease of a figure from a Fitzgerald novel. His relationship with Louise is stormy, erotic -- but, for a while, has its springtime:

Heat rush of heaving. The heart

throbbing in the inner ear, wrists twined

with a red thread of electricity, lustered response.

O Ham, she said, and swooned

in the rattled reunion and sudden summer

of thunder.

His mouth was the yes that was wished on,

feet angled in. He said, My but aren’t we?

(“The Ana of Bliss”)

However intense the attraction between the two, it is also unsustainable, given their consuming, destructive natures:

Seeded yeast in her beak and bending

down mouth to his mouth. Kisses

mismeant, reversal just lurking. Abrupt and walks off.

An abyss sunders them.

She with a love of the beautiful bordering

on excessive frivolity. He with his science and thievish

propensities. An unnatural bonhomie. He kissed her

wing and folded it

over faux fingers fretted feathers and false

all false and falling.

Mouth to her ticking. Time stopped

in a tea shop. My, doesn’t this taste? ...

(“The Raven Feeds Reynard”)

Rounding out the “cast” are a small number of other characters. One, is simply called the “Other.” The “Other” is another side of Louise -- the conscience perhaps. In “The Star’s Whole Secret,” the Other and Louise discuss this division of self:

Mother did say, Louise said, try to be popular,

pretty, and charming. Try to make others

feel clever. Without fear, what are we?

The other asked. The will, said Louise.

This division seems permanent; however, in the poem, “Louise in Love,” Louise asks the Other if they are now whole. “I think so,” says the Other. The language in this poem is cryptic, though suggestive of a return (“Much had transpired in this phantom realm”) to the dying Louise, who is taking stock, albeit in highly figurative language that is difficult to penetrate:

This elegant end

where a band tugs a sleeve,

a hand labors with an illusion

of waving away a thread. And then they came to something

big: down the block, winking red lights and a crowd

of compelling circumference.

They were one with the woman, her rosacea face,

the snapdragon terrier, ten men in black helmets, a man supine

on a stretcher. O the good and evil of accident.

The black helmets of course recall Louise herself, but here they are men, and the figure on the stretcher may or may not be Ham. It’s hard to tell just what is going on, and the answer may exist somewhere in the details of Brooks’s own life.

However, Bang’s gambles with language usually pay off. In poem after poem, Bang succeeds in suspending the reader in dream-like atmospheres that dissolve boundaries of time and place. In the lovely “A Cake of Nineteen Slices,” Louise, awaking from sleep (“She was aware of the alarm / clock in the throat of a buff-colored bird with a black head.”), considers her twelve year bout with organized religion (“the murmuring missionaries, their misguided zeal / that forever result in a hereness unused to its thisness. . .”). In this poem, Bang is at her best, juggling the balls of time and place and language with ease, and beauty.

At about a third of the way through the collection, the Other disappears, despite the joining, or reconciliation achieved, in the poem “Louise in Love.” I would of expected this particular character, given the peek-a-boo nature of the collection, to have been retained until the end. The other characters: Lydia (Louise’s sister), Charles Gordon (Ham’s brother), and a child named Isabella, have such minor roles, that I question their inclusion, since they have no corresponding equivalents in the life of Louise Brooks. This is perhaps unfair to Bang, but to some extent I think mixed signals are being sent by the author as to how closely she wants to follow the actor’s life. In one instance, Bang goes so far as to name one poem after a Brooks film (“Diary of Lost Girl”) while, in another, she creates a major plot twist out of whole cloth.

The last poems in the collection are largely devoted to Lydia (“Lydia’s Suite”). Lydia’s suicide, probably brought on by depression over Louise’s fling with Charles, seems not as fresh as the material which has preceded it. This particular melodramatic departure from Brooks’ story seems unnecessary, as if Bang felt some big event needed to mark the landscape of the story to make it a story. Brooks’ life was unusually rich in its own events and should of allowed for a closer following by Bang. Bang’s language, by its expressive nature, would have created the room needed for effective, fictional departures.

In “Lydia’s Suite,” Bang calls up Shakespeare’s Ophelia, and later (and better), Mrs. Dalloway, to send signals of madness and death -- the unforseen price for Louise’s appetites, her corrosive effect on others:

Let Death be concrete, a dream

of dual Dalmatians standing in the scattered mass,

of pure puce shirts and shattered curses.

The smell of lilac.

(“6. Enchained”)

Still, by this point in the story, the grief is not to be believed or felt. Lydia is too insubstantial for the reader to feel engaged by her fate. Bang is too good a poet, however, to not sense the need to balance her fictions. In “Raptured,” Bang seeks to pull the plot threads and personalities together, placing them all within a greater, timeless stream of Love:

With a honk and a hoot

a car pulled into the drive and Lydia stepped out.

They all came running to greet her, to tell what must be told,

and tell it well, omitting what didn’t matter

to one who had missed the day. Where had she been?

they all asked, when she had settled into a chair

in front of a billowing fire. Where, indeed?

I dreamed, she said, my death;

an ambulance and a man named Dan

took me to the morgue and you were all there, at least you

three–

she gestured to Ham, Louise, and Charles G.

Her audience sat in stunned silence as she continued

her uncommon tale of descent and ascension

into a patient brilliance. Light, said Louise.

Not quite, said Lydia.

And Love, multifaceted as it is in the life of Louise, is the theme of Louise in Love. And to some extent, theme (with Bang’s trump card: language) overrides concerns regarding a flimsy, hard to follow, narrative line. Given the elliptical sparkle of Bang’s writing, it’s a trade off I can happily live with.

For more information on Louise Brooks, visit the Louise Brooks Society’s website, which offers a comprehensive overview of the actor’s life, filmography, bibliography, photographs, etc. -

This is difficult poetry. These poems are eager for comprehension. Bang writes with a describing eye, but I think in order to see her poetry I need to see how her mind interrogates the subject. So far that's escaped me. I think these are love poems. I'm told they form a verse novel. While I can discern the recurrence of characters--the book provides a list of "Dramatis Personae"--I don't find a narrative I can follow. In their favor is a lyricism I like. Sometimes it's one musical phrase after another. But the mind wants perception. It's a hard nut. It's so tough you can't simply read it, you have to attack. This is my third attempt but I haven't penetrated the obscurity yet.

-

4.5/5

this is different, very different, from the poems i'm (now and very recently) used to reading. i love the concept and continuing theme. the poetry in this collection is incredibly lyrical which is i think why i was able to love it even though at times it didn’t make sense to me. i don’t always need poetry to make sense, but there is a balance that i've found i personally like, and while this poetry was a bit more out there the beauty of its language made it a non-issue. she still conveyed meaning well when it was important or felt important. whatever.

some of my favorite poems included “Ham Paints a Picture to Illustrate An Early Lesson: O Trauma!,” “You Could Say She Was Willful, But Compared to What?,” “Oh, Dear, What Can The Matter Be,” & “The Star’s Whole Secret.”

some quotes:

"Much had transpired in the phantom realm:

Are we whole now? Louise asked.

I think we are, the other said.

And from the mirror: no longer blue in the face, and vague;

only destiny's dove bending a broke wing and beckoning.

The ride had been open and long, the car resplendent.

What rapture, this rode into sunset. This elegant end

where a band tugs a sleeve,

a hand labors with an illusion"

—Louise in Love

"Yes, the skeleton dreaming its body back to a particular

limit—a lovely skin, a mind that knows nothing

of boundaries, the erotic singsong of motion.

The happy little cage."

—Captivity

"Night closes over. Voltaire knocks

at his daughter's window but finds instead Louise

and Lydia locked in each other's arms—

brilliant in tears, in tumult, unaccustomed to tragedy.

Audible only to V in his ghostcoat, they vow

all is forgiven in the sisterspat. L takes a flower

from her hair and gives it to L.

The other does likewise and thus

the sorority is mended. Self is safe. Pain lulled at least.

Pale, one taps her forehead once; the other twice, not a riposte

but an idiolect developed in the early days

when they were but twee girls dressed alike and spoke little and

late.

Each window locked three times, one for comfort

and twice for fear.

—Ritual Gestures -

i found this book to be incredibly dreamy & so precise with its eros. it's not overflowing nor uncontrollable--it is the pleasant reverie of emptiness, of light refracted from a gilded mirror, of the grass bent under one's weight

she lay on her back, receiving the silk drip of sleep / as it was poured from above -

Read the

STOP SMILING interview with Mary Jo Bang:

A Talk with Mary Jo Bang

By Jennifer Kronovet

Stop Smiling: Tell me about the first poem you wrote. Did that experience reflect why and how you write now?

Mary Jo Bang: I wrote it in high school, after JFK was assassinated, and after reading a lot of Ayn Rand. It was probably no more than six lines. I remember the last line was: “The man who stands alone,” which now sounds like it should be followed by a few bars of melodramatic music.

Read the complete interview... -

What is the result of leisure? I think it's so easy to dismiss the lives of wealthy people as filled with trivialities. But everyone has to deal with some kind of struggle, and Bang, here, has found how to make the struggle rooted in fancy or whim an art. The excursions seem pointless, the drama, pointless. At one point Lydia, Louise's sister, goes through an extended ordeal where it seems she's dying. In the next poem, it was just a dream! And so if the art can't really center on what is actually happening, it must revolve around how it is said. And, undoubtedly, this book rests on the language of politesse--the art of obfuscation.

-

I just read this book again, or rather the last line of the second poem kept circling my head. "Sometimes a bun, sometimes only a biscuit..." and so I googled it...and found my way back to Mary Jo. Thank god. Because lately, poetry is all I can handle anymore. And it didn't used to be this way. Maybe it's me, but I'm so sick of my half-finished novels shelf. And with poetry, well finish one and you've done something. Not all poetry. Hell, not most. But if you can find some...worth the read. Well, then.

-

amazing poetry. and it's her first book.

-

I don't care for her other books as much, but this book is fantastic. I need to revisit it soon... I think it'll help with my current project.

-

persona poems to inspire

-

Half the time I have no idea what Ms. Bang is writing about, but I kinda totally love her all the same.

-

Strange. Beautiful. Smart.

-

This is probably well-written but it didn't hit me well while I read it. My sense, at that time, was that the book felt precious and precocious and superior.

-

It has characters like a novel, and manages to be nothing like a novel.

-

Reading: participation in the construction of an artifice; the construction of a dream.