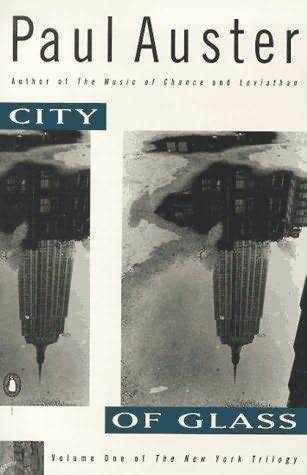

| Title | : | City of Glass (The New York Trilogy, #1) |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0140097317 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780140097313 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 203 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1985 |

| Awards | : | Edgar Award Best Novel (1986) |

Ghosts and The Locked Room are the next two brilliant installments in Paul Auster's The New York Trilogy.

City of Glass (The New York Trilogy, #1) Reviews

-

Paul Auster's City of Glass reads like Raymond Chandler on Derrida, that is, a hard-boiled detective novel seasoned with a healthy dose of postmodernist themes, a novel about main character Daniel Quinn as he walks the streets of uptown New York City.

I found the story and writing as compelling as Chandler's The Big Sleep or Hammett's The Maltese Falcon and as thought-provoking as reading an essay by Foucault or Barthes. By way of example, here are three quotes from the novel coupled with key concepts from the postmodern tradition along with my brief commentary.

On the first pages of the novel, the narrator conveys mystery writer Quinn's reflections on William Wilson, his literary pseudonym and Max Work, the detective in his novels. We read, "Over the years, Work had become very close to Quinn. Whereas William Wilson remained an abstract figure for him Work had increasingly come to life. In the triad of selves that Quinn had become, Wilson served as a kind of ventriloquist, Quinn himself was the dummy, and Work was the animated voice that gave purpose to the enterprise." ---------- Michel Foucault completely rejected the idea that a person has one fixed inner self or essence serving them as their individual personal identity. Rather, he saw personal identity as defined by a process of on-going, ever changing dialogue with oneself and others. ---------- And Quinn's interior dialogue with Work and Wilson is just the beginning. As the novels progresses, Quinn takes on a number of other identities.

In his role as hired detective (quite an ironic role since Quinn is a fiction writer and has zero experience as a detective), he goes to Grand Central Station to locate a man by the name of Peter Stillman, the man he will have to tail. This is what we read after Quinn spots his man, "At that moment Quinn allowed himself a glance to Stillman's right, surveying the rest of the crowd to make doubly sure he made no mistakes. What happened then defined explanation. Directly behind Stillman, heaving into view just inches behind his right shoulder, another man stopped . . . His face was the exact twin of Stillman's." ---------- The double, the original and the copy, occupies the postmodernists on a number of levels, including a double reading of any work of literature. Much technical language is employed, but the general idea is we should read a work of fiction the first time through in the conventional, traditional way, enjoying the characters and the story.

Our second reading should be more critical than the first reading we constructed; to be good postmodernists, we should `deconstruct' the text to observe and critically evaluate such things as cultural and social biases and underlying philosophic assumptions. And such a second reading should not only be applied to works of literature but to all our encounters with facets of contemporary mass-duplicated society.

"As for Quinn, it is impossible for me to say where he is now. I have followed the red notebook as closely as I could, and any inaccuracies in the story should be blamed on me." ---------- One key postmodern idea is that a book isn't so much about the world as it is about joining the conversation with other books. ---------- Turns out, the entire story here is a construction/deconstruction/reconstruction of a book: Quinn's red notebook. Life and literature living at the intersection of an ongoing conversation - Quinn's red notebook contains references to many, many other books, including the Diary of Marco Polo, Robinson Caruso, the Bible, Don Quixote and Baudelaire. And the story the narrator relates from Quinn's red notebook is City of Glass by Paul Auster. Again, Raymond Chandler on Derrida.

One final observation. Although no details are given, Quinn tells us right at the outset he has lost his wife and son. Quinn's tragedy coats every page like a kind of film. No matter what form a story takes, modern or postmodern or anything else, tragedy is tragedy and if we empathize with Quinn at all, we feel his pain. Some things never change.

New York City author Paul Auster, Born 1947

“Would it be possible, he wondered, to stand up before the world and with the utmost conviction spew out lies and nonsense? To say that windmills were knights, that a barber’s basin was a helmet, that puppets were real people? Would it be possible to persuade others to agree with what he said, even though they did not believe him? In other words, to what extent would people tolerate blasphemies if they gave them amusement? The answer is obvious, isn’t it? To any extent. For the proof is that we still read the book. It remains highly amusing to us. And that’s finally all anyone wants out of a book—to be amused.”

― Paul Auster, City of Glass -

(Book 219 From 1001 Books) - The New York Trilogy: City of Glass (New York Trilogy #1), Paul Auster

City of Glass, features a detective-fiction writer become private investigator who descends into madness as he becomes embroiled in a case.

The first story, City of Glass, features a detective fiction writer-become-private investigator who descends into madness as he becomes embroiled in a case. It explores layers of identity and reality, from Paul Auster the writer of the novel to the unnamed "author" who reports the events as reality to "Paul Auster the writer", a character in the story, to "Paul Auster the detective", who may or may not exist in the novel, to Peter Stillman the younger, to Peter Stillman the elder and, finally, to Daniel Quinn, protagonist.

تاریخ نخستین خوانش: ماه اکتبر سال2010میلادی

عنوان: شهر شیشه ای؛ پل آستر، مترجم: خجسته کیهان؛ تهران، کتابهای ارغوانی، سال1380، در160ص؛ شابک ایکس-964920637؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، افق، سال1394، در203ص؛ شابک9789643698768؛ موضوع داستانهای نویسندگان ایالات متحده آمریکا - سده20م

عنوان: شهر شیشه ای؛ پل آستر، مترجم: شهرزاد لولاچی؛ تهران، افق، سال1383؛ در203ص، مصور، شابک9643691314؛ چاپ دوم سال1384؛ سوم سال1386؛ چهارم سال1388؛

مترجم: مهتاب کلانتری؛ تهران، بن گاه؛ سال1395؛ در155ص؛ شابک786005268324؛

شهر شیشه ای، کتاب نخست از سری «سه گانه نیویورک» است؛ شخصیت اصلی رمان «شهر شیشه ای»، «دانیل کوئین» نام دارد؛ ایشان نویسنده ای هستند که با نام مستعار «ویلیام ویلسون»، داستانهای پلیسی، و کارآگاهی مینویسند؛ «کوئین»، به واسطه کارگزار خود، داستانهایش را به چاپ میرساند، در نتیجه کسی از هویت (نام کوئین) ایشان، آگاهی ندارد؛ شخصیت اصلی رمانهای «کوئین»، «ورک» نام دارد؛ در حقیقت، «دانیل کوئین»، فردی با سه هویت («کوئین»، «ویلسون» و «ورک») شده بود، و هرکدام از این سه شخصیت، بخشی از هویت ایشان را، شکل میدادند؛ روزی یکی با خانه ی «کوئین» تماس میگیرد، و به دنبال کارآگاه خصوصی با نام «استر» میگردد؛ «کوئین» تصمیم میگیرد، برای مسخره کردن، و دست انداختن فرد پشت خط، خود را به جای «استر» جا بزند؛ از اینجا به بعد است، که هویتی دیگر، بر ایشان افزوده میشود، و او وادار میگردد، نقش کارآگاهی خصوصی را، بازی یا ایفا کند

تاریخ بهنگام رسانی 18/12/1399هجری خورشیدی؛ 06/10/1400هجری خورشیدی؛ ا. شربیانی -

The novel is apparently written under the impression of Death and the Compass by

Jorge Luis Borges and there are many allusions to the other tales by that wizard of modern literature. Both City of Glass and Death and the Compass are the most original postmodern mysteries I ever read.Whatever he knew about these things, he had learned from books, films, and newspapers. He did not, however, consider this to be a handicap. What interested him about the stories he wrote was not their relation to the world but their relation to other stories.

City of Glass is a game – an intellectual game of a private eye and a criminal. But it’s a game of madmen – a paranoid writer pretends to be a private detective and attempts to save the paranoid son from his paranoid father.In the end, each life is no more than the sum of contingent facts, a chronicle of chance intersections, of flukes, of random events that divulge nothing but their own lack of purpose.

We all play some roles – we play ourselves and impersonate the others and in the end personifications substitute our true selves. -

Casi desde el principio de la lectura de “Ciudad de cristal” percibí un cierto aire de familia que me estaba gustando mucho (estoy seguro de que Auster será mi nuevo redescubrimiento tras un tortuoso pasado juntos). Como esta sensación persistía, busqué en Google por si había más gente que hubiera sentido la misma cercanía literaria con Vila-Matas que yo estaba observando (y que después no noté tanto o no noté en absoluto en sus otras dos novelas que conforman la trilogía). Inmediatamente olvidé mi propósito pues lo que encontré fue sorprendente.

No solo Vila-Matas había descubierto a Auster con esta novela, no solo había escrito un ensayo titulado “No soy Paul Auster”, no solo mantiene con él una admiración mutua y una relación más o menos estrecha, sino que además parece ser que fue él quien le dio al autor americano el motivo para escribir esta novela.

En su “Cuaderno Rojo”, Auster cuenta que la idea de “Trilogía de Nueva York” surgió gracias a dos llamadas de teléfono equivocadas que recibió en dos días consecutivos. Parece ser, y esto pudiera ser solo una de esas maravillosas anécdotas que solo tienen el antipático defecto de no ser reales, que fue Vila-Matas, antes de conocer al autor, por quién por puro azar se hicieron esas llamadas después de que, confundiéndolo con Salinger, le persiguiera por Nueva York, tal y como el protagonista de la novela de Auster, un escritor llamado Quinn, hace con Peter Stillman.“Nada era real excepto el azar.”

Mi comentario a toda la trilogía se puede leer aquí. -

Paul Auster, a guy who ushers you into the silky interior of his brand new Nissan Infiniti, makes sure you've got your seatbelt on, proffers bonbons, then drives you to distraction.

This book is in contravention of TWO of PB's commandments:

- Thou shalt not have a character in thy book with thy own name

- Thou shalt not portray the writing of a novel within thy novel such that the novel within the novel turns out to be the novel the reader is reading -

A very intriguing exploration of the power of language to make (and unmake) the borders of our existence and the reality we experience.

The main character, Quinn, is a writer of detective stories. One day, he decides to take on a serious detective job. His decision to do so, prompted by a mere phone call, seemingly represents the enthralling power of suggestion.

Quinn's willing engagement with the caller, and the events that unfold from there, convey a heavily slanted view of language-experience praxis. Quinn becomes helplessly swept up in the lives of his interlocutors. He is held in thrall to the extent that he becomes a blank vehicle for their tragedies and mysterious lives.

Why is this so? Auster has chosen a detective writer as a main character, whose sole means of support - as far as the reader can determine - comes from royalties from the sale of mystery books. Quinn begins the story with a knowledge of the chase, but no experience as a real detective. His real-life case, far from being an extreme case of text-to-self transference, seems to illustrate a larger truth about a dark power inherent in language, wherein word-reality has a supernatural ability to leap over cognitive barriers to create and destroy human experience.

If you're still reading this review, you may wonder if the story is really just about a guy who has a pretty straightforward psychotic break. This is entirely possible but the rest of the story makes it seem unlikely.

Context clues indicate that the story really is an allegory, representing the fragility of the human condition as portrayed in the downfall and disappearance of the book's characters. Language, in this case, is the agent of the Fall. Auster explicitly refers to the biblical Tower of Babel, mirroring the anomic results of that story with Quinn's own descent into confusion.

The characters grope with the unknown limits of their lives, including their identity, their survival, and the peace of mind they all struggle to obtain.

How does this play out in the story? The lightning rod of language is given a central agent, an insane professor (now a harmless codger) whose release from prison triggers Quinn's descent. He is summoned to protect the professor's victimized son, at which time he begins to unravel a sordid tale that eventually proves to be a gigantic McGuffin.

Behold the facts: that the professor, in his heyday, attempted to abolish language and raise his son in isolation from it. This child abuse, and the linguistic hubris from which it was born, creates a legacy of suffering which ultimately destroys all it touches. Consider also that each character affected by the professor seems afflicted by a curse: they wind up broke, insane, dead, or missing. Even the main character is powerless to stop his own descent into indigence as he continues his quixotic pursuit of the word-abolisher.

Yet what does the Professor actually do? He roams Manhattan, collecting junk, muttering nonsense.

Meanwhile, the professor's son and his wife disappear, leaving a trail of bounced checks. But Quinn is unaware or unwilling to explore these new developments. Instead he lays in wait, hoping to catch the professor before he can do any harm.

Again, unbeknownst to him, the professor commits suicide, leaving the "detective" in the absurd position of waiting for a dead man, sleeping in a dumpster and losing everything.

Finally, Quinn gives up. He returns to his apartment, his quarry lost, his paychecks bounced, and finds that a new tenant has taken his place. In search of some redemption - anything at all - he returns to the professor's son's empty apartment. His job is now meaningless, his role irrelevant. The professor and his son left him to his own vacuity, their hysterics all but sick jokes at Quinn's expense.

Now, the doors to the empty place are unlocked, seemingly in silent assent to Quinn's condition and fate. He removes his clothes and begins scribbling inane phrases in his notebook. Food appears before him as he writes, but soon he disappears. Later, we are led to understand, his notebooks serve to inform the narrator of the above events.

Now Auster's vision becomes clear. We may see a significant pattern in the impotence of the characters to prevent their demise, articulated here through an assent to participate in language games. In this absurd menage-a-trois, Auster seems to point to an innate human desire - an instinct - to interpret reality on a level of verbal/linguistic constructions, regardless of the larger implications of this praxis. Each character accepts their tragedy without question, first acceding the roles of "detective," "madman," and "victim," then "bum," "corpse," and "missing person." As this fatal flaw unravels the protagonist's author-life, the reader recalls the mysterious deaths described by Auster at the beginning of the story. In a prior life, Quinn had a family, which also disappeared. Between the end of this life and the beginning of "City," the main character developed a hunger: for companionship, for another life, for a new role to play.

Yet his hunger impelled him toward another end altogether, an inner death in the form of an overreaching projection of words on reality, the absurd "City of Glass." In becoming his own detective character, Quinn paid his final homage to the power of words, a mistake for which he paid with his home, his identity, and his mind. Babel, indeed. -

What a disaster. This is like a vastly inferior

The Crying of Lot 49. People who like it presumably call it a brilliant subversion of traditional mystery-genre expectations. I call it bullshit.

Basically there's this writer, Quinn, who gets a mysterious call looking for a detective called Paul Auster (Auster, the author, is apparently the sort of author who includes himself as a character in his books...sigh). Quinn of course takes on both the case and Auster's identity. The only good parts of the book, I think, are when Quinn tries to act hard-boiled with the stereotypical femme, which works because he's read so many hard-boiled mystery novels. Haha.

This quickly gets old as he follows a senile old man aimlessly around New York. But is this old man's wandering aimless? No! It turns out if you plot his movements on a map, they spell letters, which in turn spell words! But then those words turn out to have no bearing on the plot of this shitshow of a book. Auster abandons the heretofore somewhat interesting case, getting rid of all its characters in singularly unspectacular fashion, in favor of an identity crisis for the narrator. Quinn/Auster is so confused about his identities that he is driven insane. I've seen this before, this idea that a man with two identities or secret lives will inevitably go crazy. Whence this ridiculous notion? Actors do it with no problem, for the most part. Writers can do it, too. Clearly Auster does it himself, to no detrimental psychic effect. The whole conceit seems not only flawed but pointless, especially since the execution of the identity crisis itself is so lackluster. It's less like watching someone lose their mind and more like watching someone's grocery bag slowly rip.

I briefly had hopes that some of the threads Auster so unceremoniously dropped would be picked up in the rest of the New York Trilogy, but it looks like the novels are only linked thematically, which means I certainly will not be reading them. Seriously, fuck Paul Auster. -

نمیشود آنقدر از چیزی متنفر بود مگر آنکه قسمتی از روحمان آن را بسیار دوست داشته باشد.

به شدت از این کتاب خوشم اومد(جوری که به روزه تمومش کردم) از برخی لحاظ شبیه عامه پسند بود، ولی این کتاب خیلی جذاب تر بود -

'For if you do not consider the man before you to be human, there are few restraints of conscience on your behaviour towards him.'

It’s very hard to put the novel under the thriller-crime genre. I wouldn’t even have thought of doing that perhaps unless the book wasn’t marketed that way. Because, even when the story relates to that sub-plot, the thriller elements have the least emphasis for most of the story. I mean, of course, it is thrilling in the way it unfolds, but that’s way too unconventional for this genre. The unfolding is in a Lynchian format but the synchronization appeared to me almost like a combination of Kafka’s

The Trial with two of Martin Scorsese’s movies,

After Hours and (obviously)

Taxi Driver. More of the former than the latter, because it definitely has a Kafkaesque quality even when the existentialism is almost like a retelling from Albert Camus’ novels.

Now, I won’t tell anything about the story here, because the less you know about the plot, the better. Besides, it’s not about the plot, but more about the experience with this novella. But there are some things that I can’t keep within me. #Take a deep breath.

First of all, the pragmatic yet semi-abstract tonality at the very first of the novel, through which the entire life of our protagonist up to the point of the story’s beginning is summarized. The manner can almost be called stoical for the philosophical tone, and basically warns you about how different this story is going to be from just a traditional hard-boiled detective fiction. Not that it doesn’t have the usual traits. Even there’s a glimpse of sensuality in parts, which I didn’t expect in the ways they were presented.

Secondly, the Tarantinoesque conversations, that can simultaneously be criticized for drifting away from the topic yet admired for the concepts that shed light on, like Genesis or the actual importance of language in describing the functionality of everyday objects. I genuinely loved the Humpty Dumpty reference, amongst all. And the crime about which the novel talks, is absolutely unique in its originality as well. At least for me. But as I said at the start of this paragraph, the constant phase-ins and outs may turn out to be tiresome for the majority of the readers so be warned- this is really not everyone’s cup of tea.

It’s almost frightening as to how many works of literature were paid homage to throughout the pages, even at 133 pages, it is really dense. Firstly, Faulkner’s The Sound and The Fury, in one of the character’s monologues. Maybe it’s all in my mind, but Benjamin’s inability to maintain a linear structure in his thinking process is the first thing that does come to mind when you hear Peter Stillman jr. speak.

"I am Peter Stillman. That is not my real name. my real name is peter rabbit. In the winter I am Mr White, in the summer I am Mr Green. Think what you like of this. I say it of my own free will. Wimble click crumblechaw beloo. It is beautiful, is it not?"

And also, there’s a very fascinating homage to both

Ellery Queen, and outlandish as it may seem,

Cervantes in his

Don Quixote. The style of using the author’s name as one of the pivotal characters definitely goes back to Ellery Queen, and the reference to Cervantes is directly stated in the novel. Not only that, but the author also got past his single complaint on Don Quixote that the character Cid Hamete Benengeli, who was supposed to be the chronicler, didn’t appear once in the course of the massive novel. I mean, this one is worth reading for the weird yet fascinating stylizations (like this one) alone.

“But why did Quixote go to such lengths?”

“He wanted to test the gullibility of man. To what extent would people tolerate blasphemies, lies, and nonsense if they gave them amusement? The answer: to any extent. For the book is still amusing us today. That’s finally all anyone wants out of a book. To be amused.”

The metaphysical aspects are absolutely fabulous in the same way too. The entire novel is based in New York with accurate depictions of the city and the streets and its people, but all of that is layered with a surreal cover, (just like Kafka’s The Trial, or more appropriately in Scorsese’s

After Hours, where the protagonist roams across the city streets throughout the night but the city isn’t just the same) and the city seems to have developed a very absurd yet beguiling trance that swallows our characters. Probably that’s why the name is because the city is a significant character in the story as well. I wonder if this is where

Michael Mann had got his inspiration for Heat or Collateral?

“I have come to New York because it is the most forlorn of places, the most abject. The brokenness is everywhere, the disarray is universal. You have only to open your eyes to see it. The broken people, the broken things, the broken thoughts. The whole city is a junk heap.”

Actually, I’m quite glad that I’m reading it now, not the first time I have heard of it. Had I read it four or five years back I would honestly have wondered what the hell was going on, and would probably have never finished it.

“Time makes us grow old, but it also gives us the day and the night...Lying is a bad thing. It makes you sorry you were ever born. And not to have been born is a curse. You are condemned to live outside time. And when you live outside time, there is no day and night. You don't get a chance to die.” -

Bu kitabın en etkileyici yanı; suç, felsefe ve teolojik sorgulamaları bir araya getirip garip bir dedektiflik hikayesi üzerinden bir insanın düşüşüne bağlaması ve buna rağmen çok rahat okunan bir metin olması. Teslis metaforu, Don Kişot çıkmazı ve “yumurtalar” alegorisi eşliğinde bir polisiye . Çok acayip ve çok iyi.

-

In my review of Paul Karasik and David Mazuchelli's graphic novel version of CITY OF GLASS, I wrote: "The graphic artists give it so much dimension that the text-only version seems (in my memory) to be no more than a screenplay to this version's fully-realized presentation."

My memory was wrong. I re-read the original and found it as multi-dimensional as the graphic novel version. Or perhaps the two versions together compounded the book into something greater. Or perhaps they cancelled each other out perfectly, leaving a space empty of language(s), and in its place a kind of pure expression.

This attempt to reconcile meaning (being) and absence (nothingness) is the center of this Auster novel (if not his entire body of work), in which a man (a novelist), mistaken for another man (a detective), becomes that man, and then disappears. His project, as novelist and detective, is to investigate the meaning of language, or the language of meaning.

The short potboiler is full of doublings and disappearances: two Peter Stillman characters; two Paul Austers, two DQ characters (Daniel Quinn and Don Quixote--and two Daniels, and two Don Quixotes!), two HDs (Henry Dark and Humpty Dumpty), two William Wilsons, two older men emerging from a train, two naps in the park, two meals of eggs, two conversations about books and theories of language, two red notebooks. A yo-yo (two yo's) that travels the same path twice, and then is gone.

Auster approaches Heisenberg, Berkeley, and other philosophers with a special perspective on language: how can we name something that changes? But if we don't name something, does it exist?

(p. 26) "It was as though Stillman's presence was a command to be silent."

(p. 122) "And if we cannot even name a common, everyday object that we hold in our hands, how can we expect to speak of things that truly concern us? Unless we can begin to embody the notion of change in the words we use, we will continue to be lost."

(p. 194) "Night and day were no more than relative terms; they did not refer to an absolute condition. At any given moment, it was always both. The only reason we did not know it was because we could not be in two places at the same time."

(p. 175) "His ambition was to eat as little as possible, and in this way stave off his hunger. In the best of all worlds, he might have been able to approach absolute zero, but he did not want to be overly ambitious in his present circumstances. Rather, he kept the total fast in his mind as an ideal, a state of perfection he could aspire to but never achieve."

These quotes illustrate the purpose but not the whole elegance and taut momentum of Auster's prose. It burns quick and pure, the narrative threads and characters combusting into the ether, while the essence of the city is revealed as through a clear pane.

What do we see through it? The remnants of that city: "things that truly concern us."

(p. 122): "The brokenness is everywhere… You only have to open your eyes to see it. The broken people, the broken things, the broken thoughts. The whole city is a junk heap."

Quinn himself becomes homeless to prove this point, until he too disappears. Before he does, he takes a walk around the city, mirroring the rambles that Peter Stillman (Sr.) took earlier in the novel.

While Stillman's walks (precisely described by Auster) traced the form of letters that spelled out TOWER OF BABEL, Quinn's walk (from page 162 - 172) is only one shape, which I traced on a map of Manhattan. I'd like to say that it clearly resembles something (like a question mark), but cannot. It could be a face, or a key. In the end I have decided that it is just a walk around the city--a meaningless and pure gesture that negates the words the novelist had written, and yet contains all possibility.

*

WHY I READ THIS BOOK: Originally I read this book (in the early 1990's) because my college pal Michael Ouweleen recommended it to me… I believe it came up in connection with Saul Bellow's HERZOG, but I can't recall why. I was visiting Michael in New York City, and the experience, and then the book, had a big effect on me. I devoured everything I could of Auster's, and continue reading his novels to this day. While I have enjoyed his work (unfortunately, with diminishing enthusiasm), nothing moved me like this first novel, with the possible equal of the novel The Music of Chance or his book of essays The Art of Hunger. Re-reading it now led directly from my recent experience with the graphic novel version. -

Where do I even begin? Where could I even begin?! First off, this novel is a masterpiece, although it is definitely not for everyone for many, many, many reasons. The writing is very meta and postmodern (that is sort of what this book, and the trilogy it belongs to, is known for), some sections, while not exactly difficult or hard to follow, are intentionally obscure and offbeat in an inaccessible way, and, despite this technically being a mystery novel, there is no conclusion to anything really, there is no real climax or big payoff. Just sadness. An ongoing undercurrent of melancholy runs through practically every word of the novel, but nowhere is it more present than in the brutally tragic final chapters that made me tear up in soft sorrow.

We witness a man's fall in a unique unconventional narrative involving all sorts of sad lost souls who may or may not even exist in the first place. Nothing is certain in Auster's New York, which is likely the result of Paul Auster's own love and respect for (and eventual friend/acquaintanceship with) the fantastically tragicomic master of the absurdist novel and play Samuel Beckett, whose shadow casts a clear influence upon many parts of the novel, particularly the twisted, funny, dark, depressing, and uncomfortably sexual "speech" by the obviously mentally deranged Peter Stillman, a man whose hyperintelligent father went mad and seems to be posing a great threat against him since his release from a mental institution. Within itself, that is obviously an odd premise for a mystery novel, but Auster takes it to heights of an even more bizarre and unpredictable nature as he includes himself as a character in the novel, randomly switches from third to first person at the very, very end, speaking from the point of view of a previously unknown character, and has his text directly reference and uniquely parallel Miguel de Cervantes' immortal masterpiece Don Quixote. It's a weird, wonderful, and weary twist on the traditional detective tale, and its vibrant energy runs on an elegant, emotional, sad, and blackly humorous eloquence few authors could ever dream of remotely capturing. -

I picked City of Glass off the bookcase because I heard Paul Auster

interviewed on Radiolab. In the interview he described getting a phone call, after the novel was published, by a man asking for Quinn (the character in City of Glass who takes on the identity of Paul Auster). It sounded like an intriguing novel, and I decided to give it a chance.

It's no secret that I'm not a Paul Auster fan. At times, it seems like he is more interested in exploring identity, whether it is that of his characters or overtly himself, instead of telling a complete story. Plot is sacrificed for style, and postmodernism and metafiction shape the writing.

The novel starts with Daniel Quinn receiving a phone call asking for Paul Auster, the detective. Daniel Quinn is a writer whose wife and son died, which has caused him to distance himself from his friends and career. Quinn writes under a pseudonym, William Wilson, about a detective named Max Work. Quinn identifies with Max Work, but only through the separate identity of Wilson, his pseudonym. Without Wilson, he would be unable to Work. After getting the call again, Quinn takes on the case and becomes Paul Auster.

What layer does it add that Paul Auster has written himself into the novel? I like it when

Charlie Kaufman wrote himself into Adaptation, so why am I less thrilled when Auster does it? Part of the reason is that it seems like Auster's motives seem less about fiction and story, and more about ego. He does bring up interesting questions like what is the relationship between the writer and his characters? In the end, that's what City of Glass is interested in exploring. How we create language, how we tell stories, and who forms whom. Do the characters in Auster's head define Auster, or does he define the characters?

The other point where I diverge with Auster is how I view the universe. I don't believe in fate. I don't believe in magical coincidences being anything other than the play of statistics. I do believe in chance, but I don't put any extra importance on chance. Someone could win the lottery and their life would change. Is there special meaning in that, or is just that random events happen? A world where events and possibilities are linked by something unseen is a much safer world, but it's one that ultimately is a false world, another fiction which has been created.

As City of Glass continues, the writer who is many people slowly disintegrates and loses himself in his own fiction. He believes he is the detective and the case is real. He trusts in the circumstances and doesn't check his facts. Another key question is who is telling the story? Actually, that's not a question, because we all know that Paul Auster is telling the story, but there's another narrator toward the end of the novel, a friend of Quinn's who speaks in the first person. Here we add another layer in the identities of the author.

Lastly, Auster tries to mirror Don Quixote, which is fine, but he explains it all to the reader. Why not let that be present, and if the reader notices the similarities then it adds texture to the story. If the reader doesn't notice it, there's no harm done. Instead, it's spooned into the reader's mouth through a few pages of clunky exposition.

Overall, I appreciate Auster's exploration of writing and the relationships between characters and the writer, but feel that some elements that drive a story our sacrificed for style and ego. -

اون چیزایی که برای من جالب بود یکی بحث تحولات درونی کوئین بود و دیگری ارجاعات بیرون متنی استر - چه ارجاعات واقعی چه خیالی. داستان هم واقعا کشش داره

ترجمه ترجمه ی روون و خوبیه اما بی اشکال نیست - متاسفانه اشتباهات لپی داره مثلا ترجمه نکردن بعضی کلمات یا اشتباه دیدن یه کلمه. به نظرم هر جا دیدین ترجمه منطقا جور نیست یا زیادی مغلقه به اصلش نگاه کنید. اما به هر حال این اشکالات تا آنجا که من دیدم فراوان نیست. مترجم یه مقدمه ی چند بندی هم نوشته که بی سر و تهه -

I find that I don't know what on earth to say about City of Glass. Perhaps that will resolve itself as I read the rest of this trilogy. I was intrigued by it, at times confused; I found it easy to read, but very quiet, muted. It doesn't spark off the page and leap about, at all. It sounds as if it's going to be very strange and dramatic, and yet it quietly slims down -- in the way the main character does -- to something else entirely. And what that thing is, I haven't figured out.

Like I said, perhaps I'll understand this better when I read the rest. Or perhaps the mystery will deepen. -

An interesting PoMo novella. Auster's first novel/second book/first of his 'New York Trilogy', 'City of Glass' is simultaneously a detective novel, an exploration of the author/narrative dynamic, and a treatise on language. I liked parts, loved parts, and finished the book thinking the author had written something perhaps more interesting than important.

My favorite parts were the chapters where Auster (actual author Auster) through the narrator Quinn acting as the detective Auster explored Stillman's book: 'The Garden and the Tower: Early Visions of the New World'. I also enjoyed the chapter where Auster (character Auster) and Quinn (acting as detective Auster) explored Auster's (character Auster) Don Quixote ideas. Those chapters reminded me obliquely (everything in City of Glass is oblique) of Gaddis.

In the end, however, it all seemed like Auster had read Gaddis wanted to write a PoMo novel to reflect the confusing nature of the author/narrator/translator/editor role(s) of 'Don Quixote', set it all in Manhatten, and wanted to make the prose and story fit within the general framework of a detective novel. He pulled it off and it all kinda worked. I'll say more once I finish the next two of the 'New York Trilogy'. -

4.5 stars.

It started with a wrong number....

And this kept me hooked throughout.

It is very difficult to describe this novel as an ordinary reader without much knowledge of the factorums of literature. But I will try

It read like a nightmare - Not the scary kind, but the thrilling indecisive kind, where one loses name, identity, purpose and surrounding in the blink of an eye.

William Wilson is a defunct poet who has now assumes the persona of Daniel Quinn, the detective story writer, creator of a popular detective, Henry Dark.

He picks up a call which was originally for Paul Auster, a real detective and decides to assume his persona and investigate a man who has supposedly imprisoned and abused his young son, suffered a sentence when found out and is now returning to harm the now adult, married son, who has lost control of his faculties. His wife and nurse, Virginia is the one who has sought help.

Starting as straight forward investigation, soon we are lost in a world of Doppelganger and something almost resembling magical realism.

I was thoroughly immersed in this mesmerising world and didn't want to come out. -

امروز صبح توی اتوبوس شروعش کردم، بعد زمان برگشت بازم توی اتوبوس ادامه دادم. هر دو بار هم نزدیک بود یادم بره سر ایستگاه پیاده شم.

اولین کتابی بود که از این نویسنده می ��وندم و واقعا عجیب بود این سبک برام. هنوز هم طوری نیست که بتونم نظر بدم. بازی های نویسنده با جملات در حدی گمراه کننده بود که چند بار رفتم و متن اصل رو چک کردم و تطبیق دادم. حقیقتا ترجمه بد نبود، ولی نمی شد این کتاب رو دقیقا با همون تاثیر اصل کتاب ترجمه کرد.

هدف کتاب تفکر برانگیز بود. داستانش هم ...

+ خیلی برام جالب بود که یه سری چیزایی که معمولا توی ترجمه سانسور میشه رو کامل آورده بودن ولی شراب رو ترجمه کرده بودن نوشابه =)) خنده دار بود :-" -

A unique and memorable entry to the metafiction genre, City of Glass tells the story of Daniel Quinn masquerading as Paul Auster as he tries to find Paul Auster... it's less confusing than it sounds, I promise. What at first is a detective story becomes an intellectual sojourn into the role of literature and the meaning it places in our lives. Auster also does an exceptional job in portraying the value of the flaneur in society and capturing the feelings of New York.

It's too short to lead to anything particularly deep, but City of Glass is full of impressions, and is deserving of a read for anyone who likes postmodern literature. -

Not a real review. Just some random selection from my notes. Hope I can clarify some things for myself 'cause the book stymied me. Stymied, I says!

May contain spoilers. Probably. I have no idea, man. Just to be safe, though, I don't think anyone oughta be reading this.

1. Our main character, Daniel Quinn, wrote a series of detective novels using the moniker William Wilson. The detective's name was Max Work. When Quinn went to see Peter Stillman, he said his name was Paul Auster.

(Just a vessel for faux people. Like Peter Sellers.)

For your consideration (all from chapter 1, so not spoilers):

"Quinn was no longer that part of him that could write books, and although in many ways Quinn continued to exist, he no longer existed for anyone but himself."

--

"William Wilson, after all, was an invention, and even though he had been born within Quinn himself, he now led an independent life."

--

"He (Quinn) had, of course, long ago stopped thinking of himself as real. If he lived now in the world at all, it was only at one remove, through the imaginary person of Max Work. His detective necessarily had to be real. The nature of the books demanded it."

(Ergo... Daniel Quinn is Paul Auster?

Don't quote me on that.)

2. "In effect, the writer, and the detective are interchangeable."

3. "The world of the book comes to life, seething with possibilities, with secrets and contradictions."

(Translation: migraine migraine migraine migraine)

4. A quote from Baudelaire from the book: "Il me semble que je serais toujours bien là où je ne suis pas."

Auster translated this into: "it seems to me that I will always be happy in the place where I am not."

Another translation: "wherever I am not, is the place where I am myself."

(Ergo...Daniel Quinn is Paul Auster is Paul Auster?

Yeah.

You can see how I suck at this game.

Another phrase for sucking at something is flashing sideways)

5. From Chapter 10. Daniel Quinn talked with Paul Auster (the character, not the author...although he is a li'l bit of both. At the same time! Geeenius.) about Don Quixote.

Auster: "...Cervantes, if you remember, goes to great lengths to convince the reader that he is not the author. The book, he says, was written in Arabic by Cid Hamete Benengeli. Cervantes describes how he discovered the manuscript by chance one day in the market at Toledo..."

(Can we change "Cervantes" with "Paul Auster" and "Cid Hamete" with "Paul Auster"? Wait wait. Am I getting the order wrong?

Or "Cervantes" to "Quinn", "Cid Hamete" to "William Wilson"?)

Quinn: "And yet he goes on to say that Cid Hamete Benengeli's is the only true version of Don Quixote's story. All the other versions are frauds, written by imposters. He makes a great point of insisting that everything in the book really happened in the world."

Quinn: "...In some sense, Don Quixote was just a stand-in for himself (Cervantes)."

Auster: "What better portrait of a writer than to show a man who has been bewitched by books?"

(and yet he goes on to say that William Wilson's version is the only true version of Daniel Quinn's stoy.

In some sense, Daniel Quinn was just a stand-in for William Wilson? Or Paul Auster? No. 2, writer and detective is interchangeable...

Rauf is flashing sideways and he's flashing hard)

FFWD --

Auster again: "...But Cid Hamete, the acknowledged author, never makes an appearance....The theory I present in the essay is that he is actually a combination of four different people...."

Auster again: "....The idea was to hold a mirror up to Don Quixote's madness, to record each of his absurd and ludicrous delusions, so that when he finally read the book himself, he would see the error of his ways."

(But William Wilson, the acknowledged author never makes an appearance...is actually a combination of 4 people?

To record each of Quinn's absurd and ludicrous delusions, etc.)

Auster again: "...Don Quixote, in my view, was not really mad. He only pretended to be. In fact, he orchestrated the whole thing himself. Remember: throughout the book Don Quixote is preoccupied by the question of posterity. Again and again he wonders how accurately his chronicler will record his adventures."

(Quinn was not really mad...he orchestrated the whole thing himself. Major hint or major misinterpretation???)

FFWD again --

Auster's theory: "Cervantes hiring Don Quixote to decipher the story of Don Quixote."

(Auster using Quinn to decipher the story of Quinn?? That's a good idea for a sitcom.)

Quinn: "But you still haven't explained why a man like Don Quixote would disrupt his tranquil life to engage in such an elaborate hoax."

Auster: "That's the most interesting part of all. In my opinion, Don Quixote was conducting an experiment. He wanted to test the gullibility of his fellow men. Would it be possible, he wondered, to stand up before the world and with the utmost conviction spew out lies and nonsense? To say that windmills were knights, that a barber's basin was a helmet, that puppets were real people? Would it be possible to persuade others to agree with what he said, even though they did not believe him?

In other words, to what extent would people tolerate blasphemies if they gave them amusement?

The answer is obvious, isn't it?"

(Quinn wants to test the gullibility of men -- would it be possible to persuade others to agree with what he said, even though they did not believe him?)

I'm sure no one read this far. Now I can confess something embarassing. My favorite Godfather film is the third one!!! Phewf. Glad I got that out of my chest...

6. Another character, Peter Stillman, Sr. really believed in this theory:

"If the fall of man also entailed a fall of language, was it not logical to assume that it would be possible to undo the fall, to reverse its effects by undoing the fall of language, by striving to recreate the language that was spoken in Eden?

If man could learn to speak this original language of innocence, did it not follow that he would thereby recover a state of innocence within himself?"

IMPORTANT for the ending.

Number 7 is definitely a major spoiler. Unless I got it wrong. Then it's just a weird cherry on top of this weird sundae. You've been warned...

7. After the long discussion about Quixote and Cervantes, Daniel Quinn met Daniel Auster, Paul's little boy. Daniel Auster would be the same age as Daniel Quinn's dead son -- DQ's wife and son died at the same time.

Then D.A. said: "Everybody's Daniel!"

Just some stupid thing a kid said or important to the story?

But looking back at my notes....I don't know. I'm still stymied.

Aren't I?

Quinn made it all up? No. Paul Auster made Quinn made it all up?? That's kinda M. Night Shyamalan-y.

In the end: Quinn kept writing and writing on his red notebook ("...something about it [the notebook:] seemed to call out to him -- as if its unique destiny in the world was to hold the words that came from his pen") and then he lost his Innocence...because he was no longer "in the dark."

Quinn suffered the Fall of Language. He wanted to write about "infinite kindnesses of the world and all the people he had ever loved. Nothing mattered now but the beauty of all this. He wanted to go on writing about it, and it pained him to know that this would not be possible." -

Amerikanische Literatur findet sich in meiner Leseliste selten. Mit Paul Auster wollte ich einen Autor außerhalb der üblichen Lektüre entdecken. Das ist auf jeden Fall gelungen. Aber ob es Postmodernismus hätte sein müssen? Vielleicht war es der falsche Zeitpunkt, vielleicht die falsche Parallellektüre, aber die Geschichte um den Krimiautor Daniel Quinn, der sich in New York und der Geschichte verliert, hat mich kaum fesseln können. Zwar las es sich schnell, aber der Leser wurde immer wieder auf falsche Fährten gelockt, Handlungsstränge endeten abrupt, Rätsel häuften sich. Am Schluss blieb ein großes Fragezeichen. Ich kann mit vorstellen, dass man es gemeinsam mit anderen Interpretationswilligen mit viel mehr Gewinn lesen kann und habe durchaus die Spielereien mit Identität und der Suche nach einer Ursprache bemerkt, die mir auch gefielen, aber nicht genügend Motivation boten, weiterzudenken. Für einen New-York-Kenner mögen die genauen Beschreibungen der Wege durch die Stadt interessant sein, evtl. hätte man mit einem Stadtplan daraus ein Muster erkennen können, aber mir fehlte, wie schon erwähnt, der Antrieb dazu. Eventuell werde ich es später noch einmal mit Paul Auster versuchen.

-

Years ago, on a vacation I was without a book. At a nearby bookstore I picked out this one due to the cover attracting me. Up until then I read books of realism mostly plot driven. After the first few pages of City of Glass I threw it against the wall. My wife must have packed it. Our next stop was further out in the countryside with no bookstore in sight. I tried Auster's book again and after a few pages I fell in love with it. Thus began my ever growing interest in reading a different kind of writing.

So I went back to this book as a reunion. Waiting for the kindling again to light. Other than some sentimentality, some peeks at enjoyment, it was mainly bare leaving me at the end feeling the same way.

I'm sorry I did it. The feeling of that first literary thrill is now gone. Definitely not worth the haggard journey down memory's lane. -

Just goes to show how good of a writer Paul Auster is. Writers like him and Cormac McCarthy get away with writing stories that I can't imagine writing, let alone understanding how to keep the momentum. The protagonist, Daniel Quinn (mistaken for Paul Auster), even in his most unbelievable moments, stays believable. The metafictional aspect of this book combined with the mystery novel nature was an intriguing cerebral mind fuck that kept me reading frantically. Not a book for plot cravers (not at least in the traditional plot...big action kind of way).

-

Terrific writing. I love his prose.

-

“En su sueño, que más tarde olvidó, se encontró en el vertedero de su infancia, rebuscando en una montaña de basura.”

“— La mayoría de la gente no presta atención a esas cosas. Creen que las palabras son como piedras, como grandes objetos inamovibles, sin vida, como mónadas que nunca cambian.

— Las piedras cambian. El viento y el agua pueden desgastarlas. Pueden emocionarse.”

“— Mi trabajo es muy sencillo. He venido a Nueva York porque es el más desolado de los lugares, el más abyecto. La decrepitud está en todas partes, el desordene es universal. Basta con abrir los ojos para verlo. La gente rota, las caras rotas, los pensamientos rotos. Toda la ciudad es un montón de basura. Se adapta admirablemente a mi propósito. Encuentro en las calles una fuente incesante de material, un almacén inagotable de cosas destrozadas.”

He tenido una grata experiencia con esta lectura. Puede que el hecho de no haber leído la sinopsis ayudase, aunque el escritor es de sobra conocido. Una gran primera parte de una trilogía de sobra conocida para mucha gente, pero no para mí. Un juego literario de identidades falsas, contrapuestas, borradas, difuminadas, o incluso poco claras y que no tienen un fin concreto. Una ciudad de Nueva York tratada no solo como escenario, sino también como un personaje más, como si la ciudad respondiese a los caprichos de la trama. Un final intencionadamente absurdo, lo absurdo, el destino y de la vida. Esta falta de sentido es lo que irónicamente concede el sentido al libro. No sabría explicarlo muy bien, porque se tiene que leer para entender a lo que me quiero referir. Trata también de la vida y de la muerte, también desde una perspectiva absurda y carente de sentido, como suele ser la misma realidad. Una novela filosófica de atmosfera inquietantemente absurda, de ejecución sencilla pero con un trasfondo inmenso. Historias encerradas en un mismo marco. Policiaca, triste, de misterio, metaliteratura, filosofía, suspense, humor, incluso con rasgos cervantinos. Sobre esto último, en la novela se desarrolla un interesante debate sobre la identidad de una obra, su procedencia y la forma en la que puede pertenecer, o no, al escritor. Voy a continuar no solo con Paul Auster,sino también con su trilogía de Nueva York, la primera aparte me ha parecido inquietantemente ingeniosa. Queda seguir con Fantasmas ¿A qué fantasmas se referirá Paul Auster con su título?

Intentaré no dejar tantas reseñas pendientes, pero entre pitos y flautas se habían acumulado demasiadas reseñas, como siempre, disfruto mucho compartiendo mis opiniones por aquí. -

"What better portrait of a writer than to show a man who has been bewitched by books?"

That was fun! Auster's 'mystery' novel is not so much as a mystery as a sort of ode to Don Quixote in so much as imitation is flattery. Cervantes' work is directly mentioned and a character named Paul Auster (yeah you heard it) even gives a sort of theory about doubts concerning the book within the book in Don Quixote. The novel itself does something similar. In fact, the doubts concerning the identity of the author and identity, in general, are the main theme here.

The novel starts, for example, when the protagonist, a writer who writes detective novels under an assumed name - all about a detective named Max Work, mistakenly gets a call for Paul Auster, a detective. He ends up assuming the identity of this Paul Auster. Later he ends up trying to find this Paul Auster, the detective only to find a Paul Auster, the author - who btw is not the writer of this novel but a friend of his. Moreover, the protagonist's son shares the name with the man who called him.

There are other themes thrown in but Don Quixote's connection was quite impressive. The sentence I quoted at beginning of this review was said by Paul Auster, the writer about Don Quixote but this book itself could be said to be about a man driven to madness by books. -

I had mixed feelings going into this novel given Auster's ambiguous relationship with critics; but he pulls a rabbit out of a hat here, weaving a metaphysical "detective" novel that might be considered a primer for postmodernism. All the elements are here: the author appearing as a character, questions about what is real, works-within-the-work, etc. Auster asks the big questions and gives us a relentless work that never quite answers any of them. Auster writes a tough lean prose that reminds one of Hemingway but it keeps the pace moving furiously: stylistically he's managed to make a philosophical piece that you can read in one night. After putting the book down, I couldn't help but call it brilliant. Shades of Beckett throughout, a little Kafka, certainly some Hemingway and Melville, a little Poe, a lot of Cervantes. A great primer for anyone interested in the postmodernist novel; for the experienced, the only downside is that you feel at times that you're reading a book you've already read--The Unnamable meets Don Quixote meets A Farewell to Arms. Otherwise, a real gem, highly recommended.

-

Vamos a ver, sí me ha gustado y mucho. PERO. Hay momentos en que su pretendida “densidad” es puro esnobismo y eso casi me hace pillarle manía. Por otra parte hay muchas momentos que no interesan lo más mínimo, por ejemplo cuando el prota sigue a su objetivo y vemos su día a día de mierda. Y por ende se pasa todo el libro describiendo las calles sólo por su nombre, lo cual es una puta mierda para el que no vive en su ciudad (por ejemplo, es como si la novela se situara en Barcelona y en lugar de describir el ambiente o las calles me dedico a decir que fue por Rocafort y giró por Urgell TODO EL PUTO RATO Y DURANTE PÁGINAS). El sorprendente inicio, su brillante final y algunas cosas sueltas hacen que valga la pena.