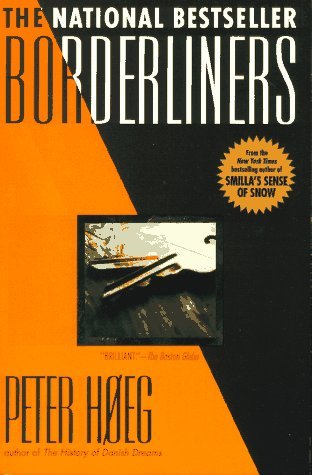

| Title | : | Borderliners |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0385315082 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780385315081 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 288 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1993 |

| Awards | : | De Gyldne Laurbær (1993), Kritikerprisen (Danish Critics Prize for Literature) (1993) |

Borderliners Reviews

-

This book has haunted me over the years. I’ve seen it a dozen times in used book stores and at library book sales and I finally decided to read it. I liked the author’s Smilla’s Sense of Snow (well, it was OK – I read it long before I started writing GR reviews). So I decided to give Borderliners a try.

It’s a fairly simple story line set in Copenhagen in the mid-1970’s. The book is translated from the Danish. Three kids, two boys and a girl, age 14 to 16 or so, are in a strict private school. They were placed there by the state because they were orphans or delinquents. (Or both – one boy killed his abusive parents.) The headmaster is running experiments to show if ‘damaged’ kids can be integrated back into society.

The school is strict and it regulates their time. There is little one-on-one interaction between the children; only incidental contact is allowed. The playground is ruled off into zones, allowing only certain kids to interact with each other. There is corporal punishment – kids are struck for misbehavior.

The children aren’t told the nature of these experiments, so the three main characters form an alliance to find out what’s happening by breaking into offices and looking at official records and teachers’ notes. They plan an ill-fated escape in which the older boy and the girl see themselves as ‘parents’ to the younger boy who is ill, physically and mentally. That’s basically it.

There is a lot of philosophical speculation on time, order, and scales of good and better. The author puts some pretty big thought into these unformed minds: “I tried to tell him that time, at the school, was being pulled downward into a spiral.” Or “Time is no law of nature…It is a plan. When you look at it with awareness, or start to touch it, then it starts to disintegrate.”

There are sections where the author turns academic on us, literally giving us a chapter or so on a “brief history of time.” Lol, and he does refer to Stephen Hawking’s book of that name, as well as making references to philosophers such as Kant, Henri Bergson, Bertrand Russell, and others.

I had a hard time with the basic premise of the book. The author sets it all up as if this social experiment was somehow Nazi-ish or Big Brotherish. As I read it, I kept thinking of Ishiguro’s book, Never Let Me Go, where the kids are being groomed to give their body parts as organ donors. Yes, the school is strict but it’s nothing beyond what you could still find today in parochial schools in the US. And, as for regulating social interaction, as bizarre as it may seem to young people today, I can recall passing from class to class lined up two-by-two in the hallway in public junior high school – NO TALKING allowed in the corridors. The purpose of the experiment seemed ok to me too: to see if these marginal (borderline) kids could be integrated back into society.

I gave it a 3.5 rounded up to 4. I note that it is relatively low-rated on GR – around 3.7.

Photo of Copenhagen from thesavvybackpacker.com

Photo of the author from bbc.co.uk -

Ever since I read

Smilla's Sense of Snow years ago, I wanted to read more by this author, but none of his books were available at my local library in those days. Last year I treated myself to plenty of online buying of used books, and this was one of quite a few

Peter Høeg titles I purchased.

It is not an easy book to read. The style is complex and a little confusing, with the narrator using 'I', 'you', and 'one' interchangeably but always meaning 'I'. Once you adapt to that, the reading gets easier, but the theme is still deep, dark, and challenging.

The narrator is a young orphan, a ward of the Danish state for his entire thirteen or so years. He has been in various orphanages and reform schools, but he begins his story while in an academy run by a man named Biehl. The narrative flows back and forth as we witness his days in this school and learn gradually of his past. We meet Katarina and August, who will become important to him and are the catalysts for everything that happens next. And we learn about the borderliners, the children who cannot be classified as A or B but are hovering in between two standard labels. How do they see the world?

The book is riveting, but I will need to reread to fully 'get it', especially the final chapters which discuss the narrator's theories of time and how Man perceives/experiences it. That may sound like a topic completely out of left field for this story, but trust me, it is quite relevant and helps to explain a great deal.

Overall, a dramatically intense book that for me will be better understood the second time around. I hope. -

Peter Hoeg

Once you have realized that there is no objective external world to be found, that what you know is only a filtered and processed version, then it is only a short step to the thought that, in that case, other people, too, are nothing but a processed shadow.

This is the experiment. There is no objective reality. Whatever we see is edited by our senses, what we see is nothing but our perception of it. The world exists because we are looking at it. And even other people aren't real, they are edited versions as perceived by faulty senses. And if that isn't real...well, then we can look at people as playthings, objects to be molded into a fashion and for a purpose, which also isn't real but fun to play with.

And that opens the door to the darkness, to where the monsters come out to fashion human beings into building blocks that can be manipulated in economic and political fashions, towards anything that satisfies the monster's lust for power. Nothing is real anyway. We are all equal in our unreality, and so the world turns grey, emotions are plasticized versions of whatever ideas we are fed, passion is purely a chemical reaction, there is no such thing as free will, and out there in the real world, buildings rise up and are built of bare concrete, also grey; economies are but massive chronological machines of human production and life and death are meaningless. They aren't real either.

And if you think this is allegory, or a fairy tale, take a look at world history! Marxism, Communism, Totalitarianism, Fascism: the monsters eagerly embrace the experiment and we have only to look at the their results to know the truth of it. But much more benign versions exist as well, some not so easily recognizable, perhaps smaller stepping stones (mixed economies and social democracies) towards the same end: government plantations, if you will.

Hoeg in Borderliners explores the one essential step towards mollifying the masses to prepare them to accept the experiment: our youth, our educational system where it all begins. In short: control human beings by controlling space and time.

The story takes place in Copenhagen's private schools and boarding schools. But, it could just as easily have been placed just North, in Sweden, long believed to be the one successful implementation of a social welfare system. If you've read Stieg Larsson's condemnation of Sweden's social policies, if you've read Mankell, or Nesbo, or just about any Scandinavian crime writer than you will be aware that the world is slowly opening its eyes as to these outright fallacies, as to this idealistic view we have towards Scandinavia. The cracks have appeared in the wall and monsters are slipping through:

High Suicide rates, social experiments on children, castration, uncontrolled immigration and asylum policies and a resultant rise in crime, Alva Myrdal (nobel peace prize winner) whose name was further tarnished in 1997 when the journalist Maciej Zaremba exposed the darkness at the core of her book from 1934 Crisis in the Population Question—which she co-authored with her husband. It is widely recognized as the founding document of the Swedish welfare state (her son publicly condemned Alva her for his upbringing), and of course, the assassination of prime minister Olaf Palmer (Swedish version of the JFK assassination)...all represent a definitive break with naivete.

Hoeg's story is about the borderliners, three children in particular: borderliners are children who do not fit into the mold as prescribed by population policies. To re-engage them into society, to assimilate them the children are placed in a private boarding school run by a man named Biehl. There, the secret experiment is unleashed upon them.

The experiment consists of bringing into the fold, borderliners, and does so by controlling a child's sense of space and time. Space is where you are at any one time, strictly regulated by the school and violated by our borderliners as part of their own counter-experiment. Time is either linear or circular and by assigning linear time to every activity in the school, and circular time to the space students are in at any time, the mind has no time to speculate, to wonder, to innovate anything. Life becomes a monotonous, droll existence seemingly one of complete determinism. Of course, to my mind, the error Hoeg makes is to imply (via our narrator) that the solution towards which the borderliners wrestle is different from the school's experiment being conducted. In reality, we know this is circular thinking. The solution to the experiment, to these three children, is to take the experiment one step further. With a nod to Edgar Allen Poe, the pair of ravens that symbolize the school's emblem also symbolize the book's very dark center.

And here I'll unleash my criticism of the book. Hoeg, unlike

Smilla's Sense of Snow (which I

loved) does not seem to be able to decide between writing this as a novel or a memoir. It is widely acknowledged that Borderliners is part autobiographical. The narrator in the book, in fact, is adopted by a family named Hoeg. On the one hand we have long, convoluted dissertations on the notions of time and space, interspersed with philosophical Kantian musings, followed by fledgling plot elements that are constantly broken by the stream of consciousness style. You may be interested in both notions, or only one, but in my opinion Hoeg fails in writing one cohesive novel as a result. I am giving this book 3 stars, for those reasons. -

When you have children, you find out that you have so much to learn. Not all of it makes sense at first. One of the things I’ve had to learn, was how to praise my child. That if your child has climbed high up on top of something and she says ‘look at me’, you’re not supposed to say ‘oh how good you are’ but rather, ‘oh look how high you’ve climbed!’ You do this to praise the action, not the child itself, so the child doesn’t think it has to do such things to have value. I think.

In part, this novel is about this. About how we value each others, how we evaluate children and students. It’s about three children, Peter, Katarina and August. Peter was orphaned at a very early age. Katarine has lived through her parents’ suicides. And August has been the offer of so much abuse that he finally snapped and killed his parents. They all attend Biehl’s Academy, an elite private school in Copenhagen, but something’s not quite right. All three have lost their parents and especially August are a troubled child. A troubled child that doesn’t belong in this particular school. So why is he there?

Peter and Katarina quickly discovers that there’s a plan with the school, there’s a plan with the students accepted to the school, with how the school is run. Trouble is, they don’t know what the plan is and they are not really allowed to talk with each other so they can figure it out. It’s pretty clear that it’s some kind of social experiment, some kind of attempt to prevent what you can call social darwinism. The school wants to take all the children, including the troubled ones, and bring them up and into the light, so to speak, by enforcing a very strict discipline. But if you choose a strict principle and stick to it no matter what, the result can be devastating even though your intention was noble in the first place. Especially in the school system if you forget that students are individuals and should be treated as such – and hitting children never do any good.

One of the things Peter and Katarina focuses on, is the question of time. How time changes depending on the situation you’re in. The importance of pauses. What lies between the lines. How there’s never been made a watch that’s precise, and what it does to you to have your entire life completely structured – and to be punished if you’re just a bit late.

This novel is slowly paced but then, all of a sudden, things happen. Crazy, painful, jarring things that makes you stop and go back and read it again to see if you really read what you think you read. And you did and your jaw drops – and then, the novel resumes it’s slow even pace and things proceed nicely and quietly. The chronology is also jumping from various points in the past to the present, making you have to stay focused all the time. I think that’s one of the reasons the slow pace works in this novel. In it’s pacing, I think it shows some of the points the narrator, Peter, makes about time. How suddenly events happen that change the way we live in time, the way we experience time. When these violent events happens in the book, you too are violently dragged into it and have to feel the immediacy of the action. Just for a few sentences. And then things slow down again and you can relax into the text once more. One of the things Peter wants to examine is if time moves faster when you���re not paying attention and I think the way Høeg wrote his book, is an example of this. When the jarring events occur, time stops for a little while – you are forced to focus and pay attention, and then, you read one and time starts flowing by again.

One thing I really love about this novel is the relationship between the grown Peter and his small daughter. How he has a hard time relating to her because of the abuse he has suffered throughout his life, the way the system failed him and he was too old before he had proper role models. But together, they find a common ground and she, perhaps, helps him most of all by just being a child, being pure feeling and reaction. She tries to bring order to her universe by listing all words she knows. She doesn’t get time at first – no children do – so she tries to understand it through other subjects that she does know. I think this relationship between father and daughter are beautifully rendered in it’s fragility.

The narrator in this book is named Peter Høeg, the same as the author. Every school and institution the narrator Peter Høeg talks about in his novel excluding Biehl’s Academy, are real and Peter Høeg has stated that the novel was the most autobiographical of his works (at that point). When it was published, it was taken as an attack on the Danish school system from a man who had experienced the worst of it himself. But later, Peter Høeg reveals that the adoptive parents in the novel are in fact his real parents, that the only autobiographical elements in the book are his first and last name, his year of birth and his parents. Which means that the novel is about him – but at the same time, that it’s not necessarily about him at all. Peter Høeg has never lived anywhere else than with his biological parents. Even though he claimed in interviews that where the institutions were real, the events taking place were also real. But with the case of the fictive Peter Høeg getting punished by having his head stuck down in a toilet, that did happen – just not to him – and so on.

The things that did happen, are instead the things that take place on the fictive school. Biehl’s Academy is called Bordings Friskole in the real world and here the author went to school for nine years – and how the teachers hit the students on a regular basis and that Peter was kicked out of school at age 16, is true – among other things.

This means, that this book is a blur between fiction and reality. There used to be a sort of agreement between readers and authors that either everything in a novel was true or else, it was false, fiction. This agreement is no longer in existence. Now authors take parts of their life or others’ lives, and use it as they see fit. In Denmark, we have seen several examples of this. And it seem to make some people angry – on the point of law suits and of people being persecuted in the medias, loosing their jobs etc. Peter Høeg does it in this novel – other examples are Knud Romer’s novel

Den Som Blinker Er Bange For Døden and Jørgen Leth

Det uperfekte menneske (apparently, neither of these has been translated to English).

For me, I love this play on reality. I think that this challenges the novel and explores the possibilities of combining fiction and reality in ways that we have never seen before. It doesn’t diminish the worth of the novel in any way. Rather, it’s the authors’s attempt to express themselves and their creativity and vision in ways they see fit. And Peter Høeg does this so very well in De måske egnede (which by the way is a much more appropriate title than the English Borderliners since the Danish title plays on Darwin’s expression of ‘survival of the fittest’. -

Nearly finished. Enjoying most of all the peculiar leakage between moments in the textual flow which disturbs any idea of a neat linear process. The novel is about the tyranny of time, and has some aphoristic points to make, as would any writer dealing with time as content. Neatly done. A flatness of delivery, possibly reverberating with the emotional numbness which affects each character in different ways, then standing out here and there an image, or a sentence or two of vivid clarity.

The teatise on 'time' towards the end is very bald but succinct; accurate too. I wonder whether the intention of the 'theory' was to present an exemplar of how coherence itself is not to be trusted, since, although the narrator 'knows his stuff' and shown himself capable of some philosophical analysis, he concludes that in life all such theories are capable of cocurrence. The point seems to be that human evil can unintentionally arise from strict adherence, one may say aanologous to a punctillious punctuality, to any system or paradigm as a way of netting humanity. Certainly this rather lovely novel celebrates despite its darkness the light of love which howsoever fragile is more steady state and 'eternal' than the wreckages as manifested in the downfall of the particular educational conspiracy describe din the book. How often we come across the rhetoric of those in power, acting with certainty and with an imperious motivation of bringing the inferior people to 'the light':

So eloquent. So well-intentioned. But still somehow totally unrelated to what really happened. As though they have had a wonderful, visionary theory about time and children and fellowship.

And then - strictly isolated from the theory - have been the actions they have carried out.

Time is a problem for us all, perhaps the problem. And it can become tyrannical in its application, appropriation rather, by those who in attempting the impossible, for time is being itself, in trying to isolate through the utter limitations of human senses and reason a diagramitical concept of time (being), a stability, a certainty, a dead thing, suffer it upon children and the world. -

''Kad kaut kas ir labāks par kaut ko citu? Tas ir svarīgs jautājums.'' (63)

Grāmata šokēja. Tas ir par maz teikts. Par internātskolām un bērnu namiem man ir ļoti virspusēja informācija, varbūt tādēļ. Tik ļoti personiska Pētera Hēga grāmata, pēc tam centos sameklēt info, vai tiešām viņš ir adoptēts 15 gadu vecumā, kā to piemin grāmatā, bet neatradu. Neapstrīdams ir fakts, ka viņš ir mācījies privātā Dānijas augstskolā, kura tolaik centās īstenot ''nepieskaitāmo'' bērnu integrāciju parastā skolā. Kas gan izdomājis šādu jēdzienu?

Manuprāt, angliskais grāmatas nosaukums Borderliners vairāk izsaka būtību. Kaut arī latviskoto versiju Varbūt viņi derēja tu saproti pēc grāmatas vāka aizvēršanas. Grāmatā Pēters stāsta par laiku 70 gadu sākuma Dānijā, bet lasot rodas iespaids, ka tas ir stāsts par kādu koncentrācijas nometni vai cietumu Otrā Pasaules kara laikā. Laikam tas šokēja visvairāk. Un nedomāju, ka daudz kas ir mainījies arī šobrīd. Stāstīts tiek juceklīgi, lēkājot kā tenisa bumbiņai, sākumā tas kaitināja, bet ātri sapratu, kādēļ tas tā ir. Pēters Hēgs paliek uzticīgs fizikai, šoreiz preperēts laiks. Vienmēr apbrīnoju, cik daudz autors ir iedziļinājies, cik daudz informācijas lasīts un apstrādāts. Pat it kā tāds sīkums par Einšteinu, kurš atdevis adopcijai savu pirmo bērnu, meitenīti, kad tai bija jau 8 mēneši !, lai tā netraucētu darbam ar relativitātes teoriju. Kā tādu nevajadzīgu sadzīves lietu! Par viņas eksistenci zināms tikai pateicoties pirmās sievas vēstulēm.

''Man ienāca prātā doma, kā tas iespējams, ka cilvēki spēj pamest savus bērnus. Kā var pamest bērnu?'' (55)

Par bērnu namiem, kur tiek ievietoti bērni ar psihiskām problēmām, vairāk dzirdēts no mūsu, aiz žoga puses. Kur kāds no šādas iestādes izbēgušais pastrādājis kādu baisu noziegumu, kas izraisījis diskusijas par nāvessoda atkalieviešanu. Bet šis ir stāsts par iekšpusi, par to pusi, kuru neesam skatījuši. Par vardarbību, izvarošanu, apspiešanu, pazemošanu, sazāļošanu, badu, aukstumu. Kurš var pateikt, kādas metodes ir labākas ar šādiem pusaudžiem? Vai pusaudzis, kas visu savu dzīvi ir smagi un mokoši vecāku sists un reiz nav varējis vairs to izturēt, pacēlis savas rokas pret tiem, uzreiz ir atzīstams kā nepieskaitāms un garīgi atpalicis? Vai šādu sakropļotu prātu spēj pavērst citā virzienā mīlestība un normāla ģimene? Tik daudz jautājumu un pārdomu, arī par pagājušā gada konfliktsituāciju Bruknas muižā, par ko mēs neesam tiesīgi spriest, jo nezinām visu patiesību. Pilnīga patiesība vienmēr būs divējāda, jo ir divas iesaistītās puses un katrai tā ir sava.

''Katedrā bija iegravēts: ''Es un mans nams, mēs kalposim tam Kungam'' un zemāk: "Tavu spārnu ēnā''.

Tātad aizsargāšana un tumsa. Kā vista savāc cālēnus zem saviem spārniem. Lai tos pasargātu no plēsīgiem putniem.

Tad iekrita prātā doma, ka skola ir gan sargātāja vista, gan Dievs, bet tai pašā laikā arī plēsīgs putns, tātad krauklis, tātad Dieva baušļu nesējs, kas medī cālēnus.'' (69)

''Lai sajustu laiku un runātu par to, ir nepieciešams aptvert, ka kaut kas ir mainījies. Un ir jāsajūt, ka aiz šīm pārmaiņām un šajās pārmaiņās ir kaut kas tāds, kas bijis jau agrāk. Laika izpratne ir pārmaiņu un nemainības neizskaidrojamā savienība mūsu apziņā.'' (183)

Zinu pavisam droši - esmu neglābjami un pamatīgi iemīlējusies Pēterā Hēgā.

Un pēc šīs grāmatas uz zirnekļu tīkliem skatīšos citām acīm :)

''Kristīgā fonda slimnīcā bija uzņemšanas nodaļa pamestiem zīdaiņiem, tur bija bērniņi boksos, tie bija mazāki par visiem citiem un tomēr izskatījās kā vecīši. Ļoti mazi un tomēr ļoti veci.'' (102) -

Endelig færdig med den bog. På ingen måde fængende… men Peter Høeg skriver som altid fantastisk. Og så er den filosofisk interessant. Ville jeg anbefale den? Måske.

-

"Mi sono svegliato di notte, la bambina si è scoperta, non so se aveva troppo caldo o paura di essere imprigionata. Le ho coperto solo le gambe, così almeno non avrà freddo. E se fosse colta dalla disperazione potrà liberarsi in un attimo. Poi non sono più riuscito a dormire, sono rimasto seduto al buio a guardarle, la bambina e la donna. E allora il sentimento è diventato troppo grande. Non è né dolore né gioia, è il peso, la pressione di essere stato introdotto nella loro vita, e di sapere che essere separato da loro significherebbe l'annientamento."

L'ho letto solo la sera, poche pagine alla volta, poche perché è stato inevitabile il dover leggere e rileggere la stessa frase, poche perché ho potuto accogliere tutto questo dolore solo in piccole dosi, un piccolo boccone alla volta, poche perché per ogni frase è stato necessario che io mi fermassi per qualche minuto per essere in grado di affrontare quella successiva.

Gli aggettivi li tralascio, bello, bellissimo, doloroso etc...ce ne sarebbero così tanti...ma preferisco il silenzio, si accorda a quello che ho ricevuto da questa lettura.

PS: grazie cara amica. -

Peter Hoeg's style is simple and yet very deep. This one in particular felt effortless in the way he continuously jumped around in the story line, and yet it wasn't confusing, it just felt like a friend confiding their life's story to you.

I greatly admire Hoeg's subtlety. He shows, in this book, the horrors of rationalizing everything, of judging, of measuring, and of discipline. The school that the characters attend is frightening not because it is so different from the schools we all went to, but because it is so similar. Everything is regulated and everyone is watched constantly. It also touches on how trying to "normalize" children who are different, even delinquent, can be violent.

A lot of interesting perspectives on time and on life. As always, Peter Hoeg gives the reader a lot to ponder. I will definitely reread this book at some point, because I'm sure there's much to be gained from reading it a second time, and I almost never reread anything.

Peter Hoeg remains one of my favorite authors and I highly recommend this book. -

Capolavoro

Quando chi ama leggere si imbatte in un libro come questo, si sente come se fosse stato baciato dalla fortuna.

Un passaggio, tra i moltissimi indimenticabili:

"Il tempo lineare è inevitabile, è uno dei modi per restare aggrappati al passato, come punti su una linea, la battaglia di Poitiers, Lutero a Wittenberg, la decapitazione di Struensee nel 1772. Anche quello che scrivo qui, questa parte della mia vita, è ricordato in questo modo. Ma non è l'unico. La coscienza ricorda anche campi, passaggi fluidi, relazioni che uniscono quello che è successo una volta con quello che succede ora, senza considerare il corso del tempo. E nel punto più lontano del passato la coscienza ricorda una pianura senza tempo. Se si cresce in un mondo che permette e premia una sola forma di ricordo, allora viene esercitata una costrizione contro la nostra natura. Allora si viene lentamente spinti verso l'orlo del precipizio." -

Triggerwarnung:

Sexueller Missbrauch an Kindern, massive Gewalt gegen Kinder. Mal wieder Danke für die fehlende Triggerwarnung. Zum Kotzen -

Once you have realised that there is no objective external world to be found; that what you know is only a filtered and processed version, then it is a short step to the thought that, in that case, other people too are nothing but a processed shadow, and but a short step more to the belief that every person must somehow be shut away, isolated behind their own unreliable sensory apparatus. And then the thought springs easily to mind that man is, fundamentally, alone. That the world is made up of disconnected consciousnesses, each isolated within the illusion created by its own senses, floating in a featureless vacuum.

He does not put it so bluntly, but the idea is not far away. That, fundamentally, man is alone. -

First time, in a very long time, that I've felt the need to underline passages...I've kept my pencil by my side. Looking forward to more Peter Høeg.

-

"Understanding is something one does best when one is on the borderline,” Hoeg writes in this book. That wisdom can be applied to borderlines of all kinds, and the 'borderliners' who straddle them. In this novel the 'border' is (primarily) between the adult and adolescent worlds, which is inhabited by children at boarding schools, but also by the staff. Some of these adults are misfits, teetering on the border of mental illness. No child in their right mind would want to 'grow up' if it means emulating the behaviors and attitudes of these 'models' of adulthood.

Being "Borderline" also describes a modern personality disorder. Emotional instability is one of its key components, along with extreme moodiness and a tendency towards black-and-white thinking. The staff who enjoy beating the children are moody and emotional unstable, and black-and-white thinking is definitely being advocated at this boarding school where the most vulnerable youngsters are being indoctrinated in cruelty, prejudice, conflict, control and other disorders of the dominant modern Danish culture which Hoeg is criticizing in this book.

Tho' i read it years ago, I was mesmerized by this story and haven't forgotten its emotional impact although the details have faded. I've searched for, and can't find the quote online, about the beating of children, and what happens to those who've done this for a long time, without remorse or reflection. Having been beaten myself as a child, I reflected upon it for a long time, and decided not to pass on to my own children that lesson of violence my father eschewed when he'd say 'might makes right'. I suspect I'm more like Hoeg, who'd advocate that 'right makes might'.

Having also been to a European boarding school in Switzerland (1968-1970), i wanted to review my own experiences through the lens of Peter's intelligence, and he did not disappoint. I LOVED his "Smila's Sense of Snow" novel and will continue to read everything he writes. -

It is hard to describe the strangeness of this book. I'd call it the uncanny of the every day, but it is not quite that. Someone else said it haunts them, and this is the case for me. It's precise and graceful and spooky. A beautiful book.

-

Terrific book, immensely complex, emotional and stressful to read.

-

Ein Buch mit düsterer Atmosphäre und zeitweilen fühlte ich mich beim lesen wirklich so, als würde ich durch eine Glasröhre gesaugt werden. Verwirrend, hoffnungslos und sehr beklemmend. Die Geschichte gibt allerdings viel Aufschluss über ein veraltetes Schulsystem, gewalttätige Lehrer und sensible Schüler. Die Schreibweise ist extrem Ausdrucksstark und enthält viele beeindruckende Bilder.

-

Nicht oft wird man von Romanen emotional so.mitgenommen. Stilistisch eindringlich,gerade aufgrund seines Lakonismus'.Bewegend, vor.allem auch durch die autobiographischen Bezüge. Philosophisch ,speziell in seinen Reflexionen über die Zeit.Absolut lesenswert.

-

Heel mooi goed en sfeervol geschreven boek. Teleurgesteld toen ik het uit had.

-

It's not a book that's easy - it being like a puzzle, I managed to get into it only towards the end of 3rd chapter. It was not at all what I expected - those strange things and suspections didn't seem that strange to me and seemed more like the hypersensitivity and aggravated preconditions of some orphaned students.

However, it's a nice essay on time (especially beginning of ch. 6 and ch. 12, and a lot in the end). It's addressing mainly the way how and why we see time, but also evaluations. In all, a fairly philosophical work. It's a good read, but I expected something more easygoing. Want to give 3, but feel like it's a rather 4 book.

>Did she know? That when one praises, one also judges. And then one does something that has a profound effect.

>When you asses others, no harm is ever intendedIt is just that you yourself have been tested so often. In the end it's impossible to think any other way.

>She, and maybe every person, was like row upon row of white rooms. You can go together through some of them, but they have no end, and you cannot accompany anyone through them all.

>In the long run, you can never be any better than your surroundings. -

Strange book.

Non-sequential (sort of) story line about a boy, Peter, who's been in institutions his whole life. He gets to a school that's being used as an experiment to incorporate both "normal" and "defective" students. He meets a girl, Katarina, who has plans for their own experiment in understanding time. She's recently orphaned. They both take responsibility for another boy, August, who killed his parents. The school's experiment fails when August kills himself. Peter's experiment continues throughout his life. -

Ci sono dei libri finiti - sembrerebbe - nel dimenticatoio, seppelliti dalla mille cose che nel frattempo ci hanno riempito la vita.

Alcuni di loro, li leggi e non gridi al miracolo, e invece il giorno dopo, una settimana dopo, un anno dopo, eccoli lì, con la forza delle frasi, forse solo una, una soltanto, ma ritorna, ingigantisce, diventa il libro intero e tu ti dici che quello è stato proprio un romanzo memorabile, e improvvisamente senti il bisogno di dirlo a tutti.

Ecco, per "I quasi adatti" il momento è giunto. -

A few interesting ideas and Høeg has definitely presented me a lot of things to think about and new perspectives, but overall this book, especially towards the end, felt like a diary of notes where Høeg has written all his opinions and thoughts on certain things and tried to express them all in this fictional novel but instead of making the reader value what he is saying, to me, makes it feel like he's just trying to get his opinions out despite their irrelevance to the story making it a bit mumbo-jumbo (muddled) and long.

-

I came to this after reading Miss Smilla etc. and wow what an assault it was - I was truly and deeply unsettled by this psychological thriller. So many reviews already have most said. Peter Hoeg is brilliant and translated his works are fantastic - I would love to know what is lost and what is gained in translation of this novel. Seriously good, seriously terrifying, brilliantly written, just fantastic.

-

Датский дом, в котором

-

Made me think about time in a new way.

-

This book is incredibly boring which made it very difficult to follow and keep my interest. It reads very much like a nonfiction book about a secret experiment in a private school.

-

I read Mrs. Smilla and Hoeg's tales each year, always at the beginning of winter, when the first snow hits the ground. I do not know why, but I was consciously staying away from his other works, perhaps out of fear that they would not live up to the high expectations set so firmly by the 2 previous books I love so much. Nevertheless, I somehow ventured to give a shot to Borderliners. At first, I was content. The language was familiar: Hoeg as I know him. A bit of philosophy, a bit of story, a bit of mist and uncertainty, ok, I said. So I read on and on and on, and it was like going through the foggy forest with no light. Nowhere. Borderliners is a pug in a greyhound disguise wanting to win the race, however, it never really sets off to sprint. I especially like Hoeg's language and am not very demanding as for the story/ plot, but here it was not enough to satisfy my intellectual hunger. I can not remember a book that bored me this much; I literally forced myself through the last 100 pages just to tick it off of my list. *** My opinion is that the book may be appealing to 1.st-time Hoeg's readers, however, it fails to compete with its (in my opinion) better-written siblings.