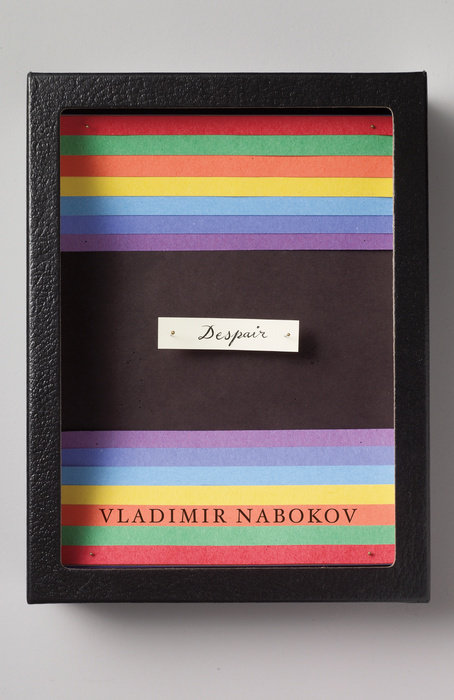

| Title | : | Despair |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0679723439 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780679723431 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 212 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1934 |

Despair Reviews

-

He's only gone and done it again. What Prose!

What truly admirable prose!

A literary virtuoso was he! I bow down to you in awe Vlad!

OK, maybe I'm getting a little over excited, and maybe he didn't hit the vast heights of Lolita or Pale Fire, but he still manages with Despair to write a prose head and shoulders above most other writers I have ever had the pleasure of reading. I can't think of any other writer (at least off the top of my head) that brings me such joyous literary moments than that spent in the company of Nabokov. That's a triple header of doubles read in recent times now, after Dostoyevsky and Saramago's take on the doppelgänger, both of which I really enjoyed.

But Nabokov I simply found superior. And its all down to that prose. Bloody hell is it good! Like a dish of Caviar, with alpine strawberries floating in a glass of champagne.

I have to pay homage to the genius translator also. Er...that would be Mr. Nabokov himself. With ease, he makes the narrative flow like a stream of liquid silk. Considering we are dealing with a novel about an insane murderer with no respect for human life, you would think it carries with it a dark or shady tone, but Nabokov fills the pages with some hilarious moments, mostly through the exceptional use of dialogue on behalf of Despair's unreliable protagonist, Hermann Karlovich a Russian living in Berlin with wife Lydia. On a trip to Prague, by complete chance, he comes across a fellow asleep on a grass verge, and low and behold he turns out to be his double.

What follows is chain of events making for a right old rollicking read! where his twisted but brilliant sense of wicked humour is on full display from the opening sentences, to its finale.

I believe this is the fifth Nabokov novel I have given top marks to. As much I loved it, and oh boy I absolutely did, it wouldn't get into my top three. That's the standard, It's a high standard at that, a very high standard actually. That puts him a pedestal above the rest.

And what's great, even though I have devoured a lot of his work already, is that, looking through his back catalogue, there is still plenty more to go!

But, easy does it kid, there is no hurry, why rush a good thing! just look forward to the next Nabokov outing. Whenever that may be... -

Intensely good writing, with the unique Nabokovian feature of phrases we've never heard before somehow moving propulsively. Unfortunately, after a promising start, the plot turns flimsy, with the "twist" at the end telegraphed far too often to be anything other than a disappointment. This is an iceberg novel, but what's beneath the surface (the book jacket copy) is likely more interesting than the ramblings of our lead, Hermann, who (in the Zweigian conceit of the novel) has written and sent the prose to Nabokov for publication.

Nabokov has an interesting line in the introduction (coming some 30 years after he wrote DESPAIR in Russian): "Hermann and Humbert are alike only in the sense that two dragons painted by the same artist at different periods of his life resemble each other. Both are neurotic scoundrels, yet there is a green lane in Paradise where Humbert is permitted to wander at dusk once a year; but Hell shall never parole Hermann."

This seems odd - though both are unreliable narrators who commit a vile crime, the insidiousness of Humbert is far more extreme, and not just because LOLITA is a superior novel. Humbert's charm makes him disturbing, while Hermann is so unlikable that we can never be immersed in his mind. Though he is fully in control of the narrative, he is mainly a source of derision.

Now, there is much pleasure here in what the reader knows and the narrator doesn't - the relationship between Ardalion and Hermann's wife is a brilliant piece of writing, with lots of great humor coming out of Hermann's not knowing what is so obviously happening. This book also has the strangest supporting character I can remember, a man named Orlovious who is somehow instrumental to the plot, in a large percentage of the book's scenes, and never once explained or described. I enjoyed the many digs at Dostoyevsky too ("Dusty") - the whole thing can be read as a Dostoyevsky parody, now that I think about it. But despite the evident strengths, this is a minor book by a major writer -3.7 stars. -

Hermann Karlovich, a self-aggrandising captain of industry, stumbles across a homeless man in a park in Prague. He inanely imagines the vagrant to be his exact doppelgänger and begins to obsess over him. Then he hatches a 'foolproof' plan to murder the fellow, so as to cash in on his own life insurance (I usually only go as far as dropping spare change into their palms).

But anyway, I digress…

I wonder if Hermann Karlovich is secretly Vladimir Nabokov's doppelgänger, because they are/were both spiteful narcissists given to petty jealousy. Authors usually leave a bit of themselves in their books anyway.

Karlovich is himself the unreliable narrator, and his manic commentary leaves the reader second-guessing everything. And there is no doubting Nabokov's genius; this idiosyncratic tale has more layers than a henhouse, and the prose is as rich as it is manipulative.

I've only read one other of his books at college (yes, that one), and am given to understand that this isn't his best.

It's still very good though. -

Wild, wicked, stylish, funny, in only the way Nabokov could write. On every page you sense the fun he's having, and boy, is it infectious.

-

Отчаяние [Otchayanie] = Despair, Vladimir Nabokov

The narrator and protagonist of the story, Hermann Karlovich, a Russian of German descent and owner of a chocolate factory, meets a homeless man in the city of Prague, who he believes is his doppelgänger.

Even though Felix, the supposed doppelgänger, is seemingly unaware of their resemblance, Hermann insists that their likeness is most striking.

Hermann is married to Lydia, a sometimes silly and forgetful wife (according to Hermann) who has a cousin named Ardalion.

It is heavily hinted that Lydia and Ardalion are, in fact, lovers, although Hermann continually stresses how much Lydia loves him.

On one occasion Hermann actually walks in on the pair, naked, but Hermann appears to be completely oblivious of the situation, perhaps deliberately so. After some time, Hermann shares with Felix a plan for both of them to profit off their shared likeness by having Felix briefly pretend to be Hermann.

But after Felix is disguised as Hermann, Hermann kills Felix in order to collect the insurance money on Hermann on March 9.

Hermann considers the presumably perfect murder plot to be a work of art rather than a scheme to gain money.

But as it turns out, there is no resemblance whatsoever between the two men, the murder is not 'perfect', and the murderer is about to be captured by the police in a small hotel in France, where he is hiding.

Hermann, the narrator, switches to a diary mode at the very end just before his capture; the last entry is on April 1.

تاریخ نخستین خوانش روز بیست و سوم ماه آوریل سال 2012میلادی

عنوان ناامیدی؛ نویسنده ولادیمیر ناباکف (نابوکف)؛ مترجم خجسته کیهان؛ تهران، تندیس؛ 1391؛ در 200ص؛ شابک 9786001820373؛ چاپ دوم 1393؛ چاپ سوم 1395؛ موضوع داستانهای نویسندگان روس تبار ایالات متحده آمریکا - سده 20م

کتاب «ناامیدی» روایت زندگی مردی به نام «هرمان کالویچ» است، که صاحب کارخانه ی شکلاتسازی است؛ این مرد که «روسی آلمانی» است در شهر «پراگ»، با مرد بیخانمانی آشنا میشود، که از لحاظ ظاهر به یکدیگر شبیه هستند؛ «هرمان کالویچ» در این داستان، همزاد خود را پیدا میکند، که میتواند به یاری آن، اندیشه های خرابکارانه، و جاهلانه اش را انجام دهد؛ این مرد «روسی» زمانیکه برای بار نخست، همزادش را میبیند زندگیش به کل تغییر میکند، و افکارش تحت تأثیر او قرار میگیرد، و اینگونه احوالش را توصیف میکند: «تا چند روز پس از آن دیدار، پریشان خاطر بودم؛ این فکر که همزادم، در تمام مدت جاده هایی که برایم ناشناس بودند را، به زحمت میپیمود، غذای کافی نداشت، سردش بود، و زیر باران خیس میشد، و شاید سرما خورده بود، به طرز عجیبی آشفته ام میکرد.»؛

نقل از متن: (به چشم انداز بیرونی خودم، زیادی عادت کرده ام، به اینکه در عین حال هم نقاش باشم، و هم مدل، پس اینکه سبکم عاری از تناسب زیبای نگارش فیالبداهه باشد، تعجبی ندارد؛ هرچه سعی میکنم، نمیتوانم به اصل خودم برگردم، یا در شخصیت قدیمی ام احساس راحتی کنم؛ اختلالی که وجود دارد، بسیار بزرگ است؛ بعضی چیزها جابجا شده اند، لامپ سوخته، و تکه هایی از گذشته ام مثل زباله، بر زمین ریخته اند

میتوانم بگویم، که گذشته ی خوبی داشتم، در «برلن»، آپارتمانم کوچک ولی جذاب بود، دارای سه اتاق و نیم، بالکنی آفتابگیر، آب گرم و شوفاژ مرکزی؛ «لیدیا» همسر سی ساله و «السی»، خدمتکار هفده سالهمان هم بودند؛ گاراژی که اتومبیل کوچک قشنگم را، در آن میگذاشتم، بسیار نزدیک بود، ماشین آبیرنگ اسپرتی که قسطی خریده بودم؛ یک کاکتوس کله گرد و قلنبه، با شجاعت ولی به کندی در بالکن رشد میکرد؛ هميشه توتونم را، از یک مغازه میخریدم، و در آنجا با لبخندی درخشان، از من استقبال میشد؛ زنم هم وقتی برای خرید تخم مرغ و کره، به فروشگاه میرفت، با لبخند مشابهی روبرو میشد؛ شنبه شبها، به کافه يا سینما میرفتیم؛ ما به بهترین لایه ی طبقه ی متوسط از خود راضی، تعلق داشتیم، یا در ظاهر اینطور به نظر میآمد؛ با اینحال وقتی از سر کار به خانه برمیگشتم، کفشهایم را درنمیآوردم، و روزنامه به دست، روی کاناپه دراز نمیکشیدم؛ از این گذشته گفتگو با زنم، در مسائل جزئی خلاصه نمیشد، و افکارم هميشه پیرامون ماجراهای ساختن شکلات، که شغل من بود، دور نمیزد؛ حتی میتوانم اعتراف کنم، که بعضی از سلیقه های خاص آدمهایی که کولی وار زندگی میکنند، از ذاتم دور نبود

و اما نظرم درباره ی «روسیه»ی جدید؛ بگذارید همینجا بگویم که در این زمینه، با زنم همعقیده نبودم؛ واژه ی «بلشویک» میان لبهای ماتیک زده ی او، با نفرتی عادی، و سطحی بیان میشد –نه، گمان میکنم کلمه ی «نفرت» زیادی قوی است؛ چیزی خانگی، ابتدایی و زنانه در لحنش بود، چون او طوری از «بلشویک»ها خوشش نمیآمد، که آدم باران را دوست ندارد (به خصوص روزهای یکشنبه)، يا کک را (به خصوص در خانه ای جدید) و برای او «بلشویسم» مثل سرماخوردگی، یک چیز مزاحم بود؛ برایش روشن بود، که واقعیت بر درستی نظرش، مهر تائید میگذارد؛ حقیقت آنچنان واضح بود، که نیازی به بحث نداشت؛ «بلشویک»ها خدا را باور نداشتند؛ این شیطنتشان را نشان میداد، اما مگر از افراد سادیسمی، و لاتهای قلدر انتظار دیگری هم میتوان داشت؟

وقتی میگفتم «کمونیسم» در درازمدت، امری بزرگ و لازم بود، تا در «روسیه»ی جدید و جوان، ارزشهای شگفت انگیزی تولید کند - اگرچه برای ذهنهای غربی نامفهوم بود، و از سوی مهاجرین تلخکام و تهیدست، پذیرفتنی نبود - و تاریخ هرگز با چنین شوق؛ از خود گذشتگی، و پارسایی و ایمان، برای رسیدن به برابری، روبرو نبوده است) پایان نقل

تاریخ بهنگام رسانی 03/02/1400هجری خورشیدی؛ ا. شربیانی -

Little silly kalliope, upon entering the pages of this despairing novel, wonders at her existence. This is all about her, or rather, about not being herself at all, but just the unoriginal existence of doubles. How come is she called like the Grand Kalliope, the Muse? They are clearly not the same. One is the doppelgänger of the other. She is clearly not the ‘one’, so she must be the ‘other’? But how can she refer to herself as the ‘other’? This baffles her and sends her mind into a spiral. She is in despair.

For a way out she looks for a mirror. Mirrors are terrifying. May be Alice will give her the clue. But no, it doesn’t; or at least not any more than any of the other books. She lives only through her reading; the only world little kalliope knows is this virtual GoodReads, where many other members of its fleeting population also have their own muses, their own shadows.

Nabokov, who also seems to be haunted by mirrors, may tell her to use cynicism and sarcasm as her path with his alluring and magical writing. The detachment that those acrimonious tones provide, help in separating one from one’s self. But no, rebuts little kalliope, that is a tiresome choice and besides it is not the separation of the ‘one’ from the ‘one’ that she is looking for but from that elusive ‘other’. Little kalliope cannot imitate what seems to be one of Nabokov’s signatures, that fine derisive tint that fascinates and captures her while also and gnawing at her patience. For quite a few pages she felt also somewhat lost, were it not for those constant strokes of violet or lilac colour that keep emerging out of the black print on white paper.

She also feels somewhat uncomfortable, for in spite of this Despair dealing with doubles, two “I” (“I” + “I” – there does not seem to be a plural for the single “I”), she does not recognized herself in this very male tone. Had Nabokov read ROOM? Asks herself kalliope as she still feels as if she just walked out of that famous Room also of her own. Although she feels she is no ‘androgynous’ reader either. She would have disappointed Woolf too.

Eventually the lilacs do lead her to find a sense in the novel, the structure or path or plot takes shape, and the light shines. She then sees Nabokov’s brilliance: the stars begin to glow. Some of the guiding posts are also literary, and these give a humorous glitter, in particular Turgy and Dusty. Are these also a Pair un-Paired?

Observing Hermann Karlovich, though, kalliope eventually realises that for her to find herself, to uncouple herself without des-pair, from that one from which she is the doppelgänger, the solution is not what he proposes in the uncanny plot. Instead, it is Nabokov’s wizardry with words, and his literary cleverness what constitute the vignettes that make her literary visit worthwhile. Little kalliope can forget the doubts on her identity and continue to follow the auspices emanating from the Grand Kalliope. – her Muse.

With or without lilacs and violets, and certainly without Despair. -

Our fabulously droll narrator is out for a stroll when he sees someone asleep under a tree. He nudges the sleeper's face with his foot and has the shock of his life. He is looking down at his own face.

Nabokov's narrator, we soon learn, lives in a kind of hall of mirrors. And who wouldn't go insane in such an abode? And he has lots of fun playing with the notion that art mirrors life or vice versa. Our hero plots a murder as a work of art. Every detail required to serve the execution of the central idea. One slip up and the entire construct comes crashing down.

The early parts of this novel show Nabokov at his comic best. A scene where he watches himself make love with his wife from a greater distance every night is hilarious. And it's an early sign of how prone our narrator is to what's become known as dissociative identity disorder, sowing the suspicion that his double probably looks nothing like him in reality. The first half of the book is a lot better than the second part when it begins running out of legs a little and even ends a little scrappy by Nabokov's exalted standards. But it's a fabulously exhilarating and clever ride for the most part. -

My second reading. The gay sub (and not so sub) text is at once hilarious and moving. Though this is essentially a caper plot. The perfect murder etc. A maniacally overconfident Russian emigre living in Weimar-era Berlin convinces himself he has found his physical double or lookalike and—after much planning and mucking about—proceeds to dress the man in his own clothes, kill him and attempt to collect the insurance. There’s one problem however; the murderer, who is also the narrator, is quite mad and not seeing things as they truly are. Thus he fails, at times hilariously. Novelist

Martin Amis has called Despair one of Nabokov’s three “immortal” books; the other two being

Lolita and

Pnin. -

Παγκόσμια ημέρα βιβλίου σήμερα και χαίρομαι ιδιαιτέρως που με πετυχαίνει κλείνοντας με Ναμπόκοφ, ναι με ΑΥΤΟΝ, αυτή την λογοτεχνική περιπτωσάρα.

Επίσης, περίοδος εμβολιασμών, με την Απόγνωση κάνω την τρίτη δόση εμβολιασμού μου κατά Ναμπόκοφ, επομένως θεωρώ ότι έχω αποκτήσει αρκετά αντισώματα σε αυτό που λέμε ανθρώπινη ιδιοτροπία, βίτσιο και άλλα όμορφα κατεξοχήν ανθρώπινα χαρακτηριστικά, που κάνουν τόσο περήφανο το μοναδικό μας είδος και δη τους καλλιτέχνες.

Καταρχάς παραδέχομαι ότι είμαι σε διάθεση ακατάσχετης πολυλογίας (αντιεμπορικό να το γράφω, το ξέρω), όμως και για αυτό πάλι αυτός φταίει. Γενικότερα, τέτοιος που είναι, μου δίνω το ελεύθερο να του προσάψω τα πάντα, όλα τα κακά της μοίρας μου νιώθω ότι μπορώ και πρέπει να του τα καταλογίσω. Κάτι σαν αντίποινα για τη δοκιμασία –αυτή την απολαυστική δεν κρύβω– δοκιμασία που με έβαλε να περάσω μέσα από την Απόγνωσή του.

Εν αρχή ην το θέαμα, και η ενορχήστρωσή του. Αυλαία, φώτα, ιδού ο βασιλιάς της ειρωνείας, ο μεγαλύτερος είρων όλων, αυτός που θα σε πάρει, αναγνώστη-θεατή, και θα σε σηκώσει, αυτός που θα σε χειριστεί όπως ο γάτος χειρίζεται ένα κουβάρι. Ναι, γλυκό μου κουβαράκι-αναγνώστη, θα σε κάνει ό,τι θέλει ο Βλαδίμηρος και στο τέλος, θα πεις κι ευχαριστώ. Το τελευταίο το λέω με απόλυτη ειλικρίνεια, χωρίς ίχνος εμπαιγμού, γιατί αυτό που θα σου έχει προσφέρει μέχρι το τέλος, θα είναι η τέρψη της Ανάγνωσης, η απόλαυση ενός σεναρίου παρανοϊκού, με ναμποκοφικά αποκορυφώματα, με πληθώρα γλωσσικών τερτιπιών και νοητικών παιχνιδιών που θα σου τεντώσουν τα νεύρα κάνοντάς τα κρόσια, με ευφυΐα του είδους που δε συναντιέται εύκολα, με λίγα λόγια χωρίς ταίρι, με σατανικές συλλήψεις και με χιούμορ του είδους που γελάς κάτω απ’ τα μουστάκια σου ή και –συχνότερα– σαρδόνιας υφής. Ναι, σε στιγμές, χωρίς να το βλέπω να ’ρχεται, με έπιανε νευρικό γέλιο σαν να βρισκόμουν ουρανοκατέβατα κατά διαβολικό λάθος σε χορωδιακή συνάντηση ηλικιωμένων υψιφώνων με uniform που τραγουδούν με κάθε σοβαρότητα το “Σ'αγαπώ γιατί είσ' ωραία, σ'αγαπώ γιατί είσαι εσύ”. Έτσι γελούσα. Νευρικά, ηλίθια.

Ο Ναμπόκοφ απαξιεί, περιγελά έξυπνα και εξυπνακίστικα, ειρωνεύεται και σχολιάζει αδιάντροπα. Μεταξύ των θυμάτων του είναι ο Ντοστογιέφσκι και ο Φρόυντ˙ τους χλευάζει καταφανώς και τους δυο στο συγκεκριμένο βιβλίο, αλλά και στη Λολίτα, όπως θυμάμαι.

Τη στιλάτη πρόζα του Ναμπόκοφ δεν μπορώ να τη συγκρίνω με κανενός του οποίου το έργο έχω διαβάσει μέχρι στιγμής. Επομένως, μένει πρώτος και μόνος στην ξεχωριστή του θέση. Πιστεύω ότι δε θα ήθελε και κανέναν για παρέα, εδώ που τα λέμε.

Η γυαλάδα του ματιού του πρωταγωνιστή της Απόγνωσης είναι εξόφθαλμη, όπως άλλωστε και αυτή του Χάμπερτ Χάμπερτ στη Λολίτα. Οι ήρωές του είναι psycho και διεστραμμένοι, over and out. Όλοι αρνητικοί, όλοι αντιπαθείς μέσα στο κυριλέ, στιλβωμένο περίβλημα της απόλυτης ευφυΐας τους. Αυτή τους η ευφυΐα είναι υπερτροφική, αυτή δημιουργεί τα νοητικά τους καρκινώματα, ενορχηστρώνει τα σατανικά τους σχέδια και παραστρατήματα, όλα αυτά τίθενται σε λειτουργία και περιγράφονται με την υπογραφή του οξύνου συγγραφέα. Δεν υπάρχει ηθικοπλαστική διάσταση και παράδρομοι με γλυκές ή γλυκερές υπόνοιες. Περιθώριο ταύτισης: ουδέν. Στιλάτο, καθαρόαιμο, ψυχρό δράμα, αυτά ναι, σε αφθονία. Αυτό είναι το μεγαλείο του σύμπαντος του Ναμπόκοφ. Εν πολλοίς, ο συγγραφέας κάνει ξετσίπωτα ό,τι γουστάρει, παίζει όπως θέλει, κι άμα θέλουμε. Αν όχι, από δω είναι η έξοδος, παρακαλώ περάστε, ευχαριστούμε για τη συμμετοχή.

Η Απόγνωση είναι ένας ακόμη νοητικός δαίδαλος, ένα καλοστημένο υφολογικό παιχνίδι με κομβικά στοιχεία τη μνήμη, έναν εκτελεσμένο φόνο με ειδικές, βιτσιόζικες προδιαγραφές και βιρτουόζικη εκκίνηση της ιδέας του, και την επιθυμία εκτέλεσής του έχοντας αποκλείσει το παραμικρό περιθώριο λάθους. Το τελευταίο δε θα συγχωρούνταν επουδενί, όπως δε συγχωρείται και δε γίνεται αποδεκτό οτιδήποτε λιγότερο από ένα αριστούργημα στον καλλιτέχνη που αναζητά το τέλειο, το άψογα εκτελεσμένο. Επέτρεψα και πάλι συνειρμούς στο φτωχό μου μυαλουδάκι. Σκεφτόμουν το Δημιούργημα του Zola και την ένταση του άγχους και της απόγνωσης –ναι, και εκεί απόγνωση!– του καλλιτέχνη που ξετυλίγεται εκεί μεγαλοπρεπώς. Από την πένα όμως του νατουραλιστή λογοτέχνη. Εδώ έχουμε μια αντίστοιχη απόγνωση, revisited όμως, αποδοσμένης με την πένα του μοντερνιστή Ναμπόκοφ. Εδώ έγκειται ο διαχωρισμός. Ενώ η κεντρική ιδέα μοιάζει να είναι όμοια, ο αφηγηματικός τρόπος δημιουργεί τη μεγάλη διχάλα και μιλάμε πια για κάτι το τελείως, το εκ βάθρων διαφορετικό πράγμα.

Η Απόγνωση είναι εντέλει μια εξαιρετική παράσταση. Μια παράσταση παιγνιώδης και πανέξυπνη όπου χρειάζεται η συνέργεια όλων των εγκεφαλικών κυττάρων του αναγνώστη –τα φαντάζομαι εν χορώ– για να ρουφήξουν κάθε ρανίδα ευστροφίας, χιούμορ και φυσικά ειρωνείας που προσφέρονται αφειδώς στις σελίδες, από την εναρκτήρια παράγραφο (Αν δεν ήμουν απολύτως βέβαιος για το ταλέντο μου στο γράψιμο και τη θαυμαστή μου ικανότητα να εκφράζω ιδέες με υπέρτατη χάρη και ζωντάνια… ) μέχρι το γκραν φινάλε.

Το βάπτισμα του πυρός με τον Ναμπόκοφ το πήρα με την Άμυνα του Λούζιν και μετέπειτα με τη Λολίτα, δείγμα ικανό για να δείξει εάν έχω δυσανεξία ή όχι στην αυτού εξοχότητα. Όχι μόνο δεν έχω, αντιθέτως. Με την Απόγνωση επισφραγίζω μια λογοτεχνική μου αδυναμία.

* Έχω βάσιμες υποψίες ότι από τον τάφο μέσα, τρίβει τα χέρια του μειδιώντας σαρδόνια και σαρκάζοντας αυτάρεσκα "Άντε να πληρώνετε 350€ για τη Χλομή Φωτιά γλυκάκια μου. Τα αξίζω και με το παραπάνω, αν θέλετε τη γνώμη μου."

* Θέλω διακαώς να σας δώσω λίγο να δοκιμάσετε. Κάπου στη μέση του βιβλίου, εντελώς ξεκούδουνα, ξεκινάει ένα κεφάλαιο ως εξής: «Καταρχάς, ας δεχτούμε το ακόλουθο απόφθεγμα (όχι ειδικώς γι’ αυτό εδώ το κεφάλαιο, αλλά γενικώς): Λογοτεχνία ίσον έρωτας. Τώρα, μπορούμε να συνεχίσουμε.» Ναμπόκοφ, αγόρι μου, πώς μας παίζεις έτσι στα γόνατά σου;

* Το επόμενο γατί μου θα το πω σίγουρα Βλαδίμηρο, ή Βλάντι, ή Νάμπι, ή κάτι τέτοιο τέλος πάντων.

* Χαμογελάς, ευγενή αναγνώστη; Καλά κάνεις!

(Εύσημα στον Αύγουστο Κορτώ για την άψογη μετάφραση) -

Only one author on earth can produce from me the following sentence: “Yeah, I’m reading this book called Despair about an insane murderer with no respect for human life, and it is HILARIOUS.” That author is Nabokov.

In this, one of his lesser-known works, the egotistical and foppish narrator confesses to murdering someone who looks exactly like him in an attempt to collect his own life insurance money (and, more subconsciously, to rid the world of his weird doppelganger). Of course, Vladdy isn’t satisfied with a straight-up story, and slowly reveals that the first-person narrative we’ve been reading is really only just scrapping surface of what actually took place.

As always with Nabokov, the language is beautiful and you are sure to learn at least a few new and awesome vocabulary words. You are also sure to either 1) write a bunch of new fiction with a weak, pseudo-retarded version of Nabokov’s style or 2) become paralyzed completely.

Despair was one of his earlier novels, written in Russian in 1932 and then translated into English (by Nabokov himself, the goddamn genius) with extensive edits, in 1965. It’s absolutely fascinating to see a younger, less experienced Nabokov write - you can see all of the seeds of his future works. The themes that he returns to so often during the latter part of his career — mirroring, unreliable narrators, unlikable protagonists, mistaken identities, dark humor, botched violence - are here, too, a little more apparent and a little less smooth and adept.

As a writer, I was happy to see a lower-level Nabokov - unlike in say, Pale Fire, where it is hard to pinpoint how he is pulling off the literary tricks he pulls off, in Despair, it’s a little easier to look into Nabokov’s mind and see the blueprints he was working with. For example, while it is hard to tell how he so subtlety reveals that Pale Fire’s protagonist is delusional, in Despair, I could pick up on specific techniques he was using to create Hermann, the book’s unreliable narrator. It’s sort of like watching a magic trick before the magician has perfected it — you can maybe glimpse a trap door or a string and get a clue as to how to execute it yourself.

And while the exacting and masterful art of his later books is partially missing, his weird, twisted humor is on full display from the first page to the last. It might be the best kind of joke - 240 pages of non-stop dramatic irony which becomes more and more obvious with each page (all while the “author” is forced to continue complicating the story in order to continue deluding himself). And even while Nabokov can pull off a novel-length leg-pull, he also appreciates and condones the lowest forms of humor - puns and fart jokes. There truly was never a greater writer, and I mean that from the bottom of my heart. -

I like Nabokov, but halfway through this book I was almost ready to quit. The plot was getting nowhere, the characters were cartoon-like, I couldn't connect with the narrator, there was a total lack of any worthwhile insight - all these, combined with the pompous, turgid language, heavily peppered with arcane, archaic and even self-made(!) words, made the reading a hard slog.

The final part of the book, however, was a lot better. A few inventive twists managed to upend this clumsy, antiquated thriller and turn it into a philosophical fable about the novelist and their craft. 3.5 stars - rounded up because I like Nabokov.

PS: Does anyone know what 'curdom' means? Is it actually a word? -

1η δημοσίευση, Book Press:

https://bookpress.gr/kritikes/xeni-pe...

[Ένας… απεγνωσμένος οδηγός ανάγνωσης του Ναμπόκοφ]

«Σε κάθε έργο τέχνης, το ύφος είναι μια υπόσχεση»

Μαξ Χορκχάιμερ

Ο ουρανός στα τοπία που δημιουργεί με περισσή μαεστρία ο Ναμπόκοφ δεν είναι ποτέ ανέφελος. Ο αναγνώστης του γνωρίζει εξαρχής ότι τον περιμένει μια κάποια νοητική δοκιμασία. Υποψιασμένος εισέρχεται με αίσθημα ανησυχίας, οσφραίνεται τις σελίδες, αναζητώντας τις παγίδες που με μαστοριά έχει στήσει ο δημιουργός. Η «Απόγνωση» δεν πρόκειται να τον διαψεύσει στο ελάχιστο.

Ο Ναμπόκοφ οδηγεί εκουσίως και με ασυγκράτητη απόλαυση τους ήρωες και τους αναγνώστες του βιβλίου του στην… απόγνωση. Θα μπορούσε κάποιος να πει ότι υπάρχει κάτι κρυφά σαδιστικό στον τρόπο με τον οποίο ο συγγραφέας αντιμετωπίζει τους εμπλεκόμενους στο έργο του. Περισσότερο και από άλλα έργα του, στο συγκεκριμένο, επιχειρεί να προσπεράσει τους… περαστικούς, τους φυλλομετρητές, εκείνους που χαρακτηρίζει ανώριμους.

Αυτό το βιβλίο έχει ενδιαφέρον να ιδωθεί μέσα από δύο προοπτικές: του πώς απωθεί και το πώς προσελκύει το κοινό του, καθότι θεωρώ είναι εξίσου σημαντικές για τη συνολική κατανόηση του έργου του παρεξηγημένου (από τους αναγνώστες, όχι τους κριτικούς) Ναμπόκοφ και της αξεπέραστης δημιουργικής του ιδιοφυίας. Η απώθηση είναι το πρώτο και πιο ενδιαφέρον σημείο, οπότε ξεκινώ από αυτό.

Πιστός σε όσα έχει ήδη θέσει στα θεωρητικά του κείμενα ή στις διαλέξεις του (οπαδός του ρωσικού φορμαλισμού, Βίκτορ Σκλόφκσι κλπ.), ο συγγραφέας κάνει πράξη ήδη από τις πρώτες σελίδες όσα διακήρυττε. Αποτρέπει με κάθε τρόπο την ταύτιση, καθότι παιδικό στάδιο της ανάγνωσης, του αναγνώστη με τους ήρωές του. Όσο κι αν ψάξουμε, δύσκολα θα βρούμε συμπαθή ήρωα στα μυθιστορήματά του (προεξαρχούσης της Λολίτας), κάτι που ισχύει και στην περίπτωση της «Απόγνωσης» (σε εξαιρετική μετάφραση του Αύγουστου Κορτώ!). Ο Χέρμαν είναι τουλάχιστον ύποπτος, αναξιόπιστος και συχνότερα αντιπαθής πρωταγωνιστής. Η πρωτοπρόσωπη οπτική του βιβλίου διόλου δεν συμβάλλει στην ωραιοποίηση της εικόνας του (μία από τις πολλές ανατροπές). Υπερόπτης και αλαζόνας, διαστρέφει και παραποιεί κατά το δοκούν τα γεγονότα, εξυμνώντας τον εαυτό του, τις δυνάμεις επινόησης και χειραγώγησης όλων εκείνων που τον πλαισιώνουν, ακόμα κι όταν οδηγείται στο έγκλημα.

Βγάζοντας από το πλάνο την πρωτόλεια ταύτιση του ανώριμου αναγνώστη με τον ήρωα, ο ευφυής συγγραφέας συνεχίζει την τακτική απώθησης με το δεύτερο, (εξίσου ανώριμο κατ’ αυτόν) επίπεδο ταύτισης του αναγνώστη με την πλοκή τού έργου. Επιτυγχάνει άψογα και ως προς αυτό. Η ιστορία που διηγείται δεν είναι κάτι σπουδαίο, εξαντλείται στην εμφάνιση ενός σωσία (ονόματι Φέλιξ) του ήρωά μας ήδη από τα αρχικά κεφάλαια, και συνεχίζει στον τρόπο με τον οποίο ο δαιμόνιος και ψυχικά ασθενής Χέρμαν επιχειρεί να εκμεταλλευτεί προς όφελός του την παρουσία του, αποτυγχάνοντας θεαματικά. Προφανώς, κατά την πάγια τακτική του Ναμπόκοφ δεν υπάρχουν ηθικά διδάγματα, «ιδέες» και κοινωνικές αλληγορίες που θα προσφέρουν οποιοδήποτε όφελος στον αναγνώστη που επιζητά «νόημα» στο βιβλίο που διαβάζει. Κατ’ αυτόν τον τρόπο, ο λόγος του δεν ρέει με την τρέχουσα έννοια, ενώ οι τόσο διεκπεραιωτικοί για τον αναγνώστη διάλογοι εκλείπουν (γνωστή η απόφανσή του πως αν ένα βιβλίο έχει πολλούς διαλόγους, είναι ανάξιο λόγου). Ο συγγραφέας πριονίζει συνεχώς το «κλαδί» της εύκολης, απρόσκοπτης, ράθυμης ανάγνωσης, εστιάζοντας στο εσωτερικό της σκέψης του προβληματικού πρωταγωνιστή με αμιγώς μοντερνιστικό τρόπο, παρεμβάλλοντας εικόνες και οπτικές, βάζοντας συνεχώς τρικλοποδιές στον αναγνώστη.

Η ειρωνεία συμβάλλει τα μάλα ως προς αυτό. Ο άσπλαχνος συγγραφέας προσφεύγει συχνότατα σε αυτήν, στρέφοντας την αιχμή της ενάντια στους αναγνώστες, στους ανθρώπους εν γένει (η λέξη όχλος κυριαρχεί), στη θρησκεία, την πολιτική. Αλλά και τα λογοτεχνικά είδη δεν ξεφεύγουν από την καυστική του ματιά: το είδος της επιστολογραφίας διακωμωδείται, ενώ δεν παραλείπονται ούτε οι άλλοι συγγραφείς. O Όσκαρ Ουάιλντ «με τις ομορφούλικες ιστορίες του, τις αμυδρώς λάγνες και παραδοξολόγες», οι αστυνομικές αφηγήσεις τύπου Ντόυλ και Λεμπλάν και οι συγκρίσεις του με τον Ντοστογιέφσκι. Είναι γνωστή η αντιπάθειά του για τον μεγάλο λογοτέχνη, κυρίως εξαιτίας του ρωσικού μυστικισμού και αντιδυτικισμού του, στοιχεία τα οποία ο καθ’ όλα δυτικής διαμόρφωσης Ναμπόκοφ απεχθανόταν βαθύτατα.

Αφαιρώντας τα λεγόμενα εξω-καλλ��τεχνικά κριτήρια από τη μέση (ταύτιση με πρωταγωνιστή/ πλοκή), ο Ναμπόκοφ επικεντρώνεται σε αυτό που είναι το μείζον για εκείνον και για τους πιστούς του αναγνώστες. Ο καχύποπτος θα αναρωτηθεί εδώ με δυσφορία περί τίνος πρόκειται, εφόσον ο συγγραφέας έχει ήδη, κατ’ αυτόν, εξαρχής ενταφιάσει την όποια αναγνωστική ηδονή, τοποθετώντας τη στην προκρούστεια κλίνη, αφαιρώντας συνεχώς στιβάδες, ώστε να απομείνει ένα αποστεωμένο κουφάρι. Κι όμως…

Η εύκολη και γενικευτική απάντηση είναι ότι στην τέχνη υπάρχουν άμεσες απολαύσεις που εξελίσσονται τάχιστα και εξαχνώνονται εξίσου γρήγορα, αφήνοντας πίσω ένα απλό μετείκασμα και μια μη περίοπτη θέση σε σκονισμένο ράφι. Από την άλλη η μεγάλη τέχνη απαιτεί προσήλωση, νοητική προσπάθεια που θα οδηγήσει στην ευκταία ζεύξη μεταξύ συγγραφέα και αναγνώστη. Διατρανωμένος στόχος του -μέτρο και απώτατο όριο του οποίου αποτελεί το corpus των βιβλίων του- η ταύτιση του οτρηρού αναγνώστη με τον συγγραφέα. Όχι βεβαίως τον άνθρωπο (μας είναι αδιάφορος), αλλά με τον Επινοητή, τον Μυθοπλάστη που υφαίνει στον αργαλειό του έργα φαντασίας, με συγκολλητικό υλικό το ιδιαίτερό του αφηγηματικό ύφος. Για ετούτη την προσπάθεια ανταμείβει με απόλαυση διαρκείας που αγγίζει τον πυρήνα της ύπαρξης αφήνοντας τα σημάδια της στον πεπερασμένο βίο μας (η διεύρυνση του αυτόνομου εαυτού κατά H. Bloom). Οφείλω όμως να σταθώ σε συγκεκριμένα σημεία που θεμελιώνουν τη γενικότερη αυτή στάση.

Για τον Ναμπόκοφ, η λογοτεχνία (κατά το παράδειγμα του Φλωμπέρ) είναι αφενός δημιουργία εικόνων, αφετέρου παιχνίδι, νοητικό παζλ που απαιτεί την εγρήγορση του αναγνώστη. Προκαλεί συνεχώς το πνεύμα του, ναρκοθετώντας τις παραγράφους του με κλειδιά ερμηνείας (όχι ιδέες!) που απαιτούν προσήλωση, προκειμένου να κορφολογηθούν από κάθε κεφάλαιο με προσοχή και, το σημαντικότερο, υπομονή. Ο συγγραφέας είναι εκείνος που καθορίζει τον τρόπο και τον χρόνο, σε αντίθεση με τους πιο εμπορικούς ομοτέχνους του που ακολουθούν τον ρυθμό του αναγνώστη (θέλει ταλέντο κι αυτό), ώστε να κρατήσουν αμείωτο το ενδιαφέρον του. Ο Ναμπόκοφ αποστρέφεται την τακτική αυτή, ο ρυθμός υπαγορεύεται αποκλειστικά από εκείνον με τον αναγνώστη να ακολουθεί τα βήματα ενός χορού του οποίο είναι ακόλουθος και όχι προεξάρχων.

Περί αισθητικής απόλαυσης, λοιπόν, ο λόγος. Η απόλαυση αυτή δεν προέρχεται από τις εντάσεις, τις συγκρούσεις, το σασπένς και όλα τα κόλπα τα οποία χρησιμοποιούν άλλοι συγγραφείς. Ο Ναμπόκοφ υπενθυμίζει συνεχώς ότι δεν είναι ένας από τους άλλους, τους κοινούς. Είναι ο Άρχων της ψευδαίσθησης, του ψέματος, του συγκαλυμμένου λόγου, αλλά ταυτόχρονα της αναπαράστασης, της ερμηνείας, της αποστασιοποίησης. Εν ολίγοις, όλων εκείνων που δεν είναι ρεαλιστική αναπαράσταση. Επιτίθεται, λες με μανία, ενάντια στην υπάρχουσα τάξη πραγμάτων, όχι ως ιδεολόγος πολιτικός επαναστάτης (όντας γνήσιος εστέτ καλλιτέχνης ήταν βαθύτατα συντηρητικός), αλλά ως αναρχικός της πεφωτισμένης αισθητικής δεσποτείας. Τον ακούμε από την Ολύμπια κορυφή να λέει: «Αυτή την ιστορία που οι άλλοι θα την αφηγούνταν κοινότοπα, Εγώ θα τη διαστρέψω, θα τη διακωμωδήσω και θα την περιτυλίξω με τον μανδύα της επινόησης, ώστε εσύ αναγνώστη να χρειαστείς όλη σου τη φαντασία, τη διαύγεια και αυτοσυγκέντρωση για να την ολοκληρώσεις επιτυχώς. Η ανταμοιβή σου όμως θα είναι αντίστοιχη της προσπάθειας».

Θα μπορούσα να σταθώ σε πληθώρα σημείων που ο δημιουργός αποδεικνύει τη μεγαλοφυία του, αλλά θα απαιτούσε σελίδες. Στέκομαι μόνο σε κάποια από τα πλέον οφθαλμοφανή κατά την κρίση μου. Καθ’ όλη την έκταση του κειμένου επιχειρείται σύγκριση μεταξύ λογοτεχνικού έργου και τέλειου εγκλήματος, καθώς ο Χέρμαν χρησιμοποιεί τον σωσία Φέλιξ για ιδικούς του σκοτεινούς σκοπούς. Ο εγκληματίας/πρωταγωνιστής/περσόνα του συγγραφέα (αλλά συγγραφέας κι ο ίδιος) πασχίζει να καταγράψει στις σελίδες την πορεία του. Το βιβλίο ξεκινάει επιδεικτικά με το γεγονός ότι τίποτα από όσα διαβάζουμε δεν θα υπήρχε δίχως τις δυνάμεις επινόησης του πρωταγωνιστή (alter ego του Ναμποκοφ), καθώς η μέγιστη συγγραφική του δεξιότητα το καθιστά υπαρκτό. Ξεκαθαρίζει εξαρχής ότι η όποια αλήθεια δεν είναι εδώ το διακύβευμα, αλλά ότι η «αλήθεια» υφίσταται μόνο ως προϊόν επινόησης – και μάλιστα ανώτερης τάξης. Ο Ναμπόκοφ δικαίως επαίρεται: «Εγώ ειμί η αλήθεια!» και ο αναγνώστης εισέρχεται στο περίκλειστο, αυτιστικά μεγαλειώδες σύμπαν του Δημιουργού, έχοντας αφήσει στην είσοδο τις όποιες αντιρρήσεις του.

Οι εγκληματικές πράξεις, ο τρόπος με τον οποίο πειθαναγκάζει, διαστρέφει, εκβιάζει και παραποιεί την αλήθεια, συγκρίνεται σε κάθε της βήμα με τη δημιουργική διαδικασία, καθώς η μία δεν υφίσταται χωρίς την άλλη. Ο δημιουργός είναι ο ιδανικός εγκληματίας, ο αείποτε λοξίας. Κι αυτή την αυταπόδεικτη για τον Χέρμαν/ Ναμπόκοφ αλήθεια, ο «όχλος αρνείται, επί μακρόν, να κατανοήσει», αναζητώντας ολισθήματα στη σκέψη του. Βεβαίως σφάλλουν, καθότι τους λείπει η οξύτητα της ματιάς του «και δεν διακρίνουν τίποτα το ασυνήθιστο εκεί που ο συγγραφέας αντιλήφθηκε ένα θαύμα». Και θαυματοποιός λοιπόν ο δημιουργός. Λογικό άλμα δεδομένου ότι από τον πηλό του υπάρχοντος πλάθει μια νέα πραγματικότητα – ένας μικρός Θεός που δίνει πνοή σε κυήματα, ενεργούμενα.

Και σε αυτό το βιβλίο πράττει εκείνο που στη συνέχεια τελειοποίησε με τη «Λολίτα». Αναλαμβάνει την υπεράσπιση του εγκληματία, του ουτιδανού, και τον αθωώνει στο Ανώτατο Δικαστήριο της Υψηλής Τέχνης. Αδειάζει πλήρως το περιεχόμενο από οποιαδήποτε προφανή ηθική κρίση, υποκαθιστώντας τη με την αισθητικής φύσεως (η οποία με τη σειρά της είναι ηθική). Με την υπεροψία της ιδιοφυίας παραδίδει στο άχρονο κοινό έργα που υπερβαίνουν τις όποιες μόδες και καθιστά το ανθρώπινα ατελές, καλλιτεχνικά άρτιο.

Για να επανέλθω στο βιβλίο μας, ο Χέρμαν επιθυμεί να εξαπατήσει τους πάντες. «Κάθε έργο τέχνης είναι μια εξαπάτηση», μας υπενθυμίζει ο Ναμπόκοφ. Είναι φυσικά πεπεισμένος για την τελειότητα του έργου του, όμως επιθυμεί να το αναγνωρίσουν και οι άλλοι, επιθυμεί την επιτυχία. Δεν είναι επομένως απορίας άξιο το γεγονός ότι προσβάλλεται όταν το σχέδιό του, η δημιουργία του κρίνεται ελλιπής, αποκαλύπτεται ως απάτη. Ο ίδιος μόνο έχει το απόλυτο δικαίωμα να εξαπατά το κοινό, αλλά επουδενί να αποκαλύπτεται ως εξαπατών. Την ίδια στιγμή αρνείται το ενδεχόμενο, κατ’ αυτόν δεδομένο, ότι ο σωσίας του δεν ήταν τελικά και τόσο…όμοιος με εκείνον. Αδιανόητο, καθότι η συλλογιστική του και συνολικά το δημιούργημά του εξαρχής βασίστηκε σε αυτή τη συνθήκη απόλυτης ομοιότητας.

Διόλου τυχαία παρομοιάζει τους ερευνητές-αστυνομικούς με κριτικούς λογοτεχνίας που εμφανίζονται εκ των υστέρων, με επιχειρήματα τα οποία δικαιώνουν την αρχική τους αντιπάθεια. Εκ νέου ο εγκληματίας ταυτίζεται με τον συγγραφέα, του οποίου το μεγαλόπνοο έργο γίνεται βορά στις ανόσιες αισθητικές αναλύσεις μη επαρκών κριτών. Τα όποια λάθη αποδίδονται σε αυτόν δεν μπορεί να αμαυρώσουν το μεγαλείο της σύλληψης, της τελειότητας του σωσία. Δεν υπάρχει κάτι για το οποίο ο Δημιουργός οφείλει να μετανοήσει. Παραδίδει το έργο του στο κοινό. Ο όχλος χλευάζει ως είθισται. Ο καλλιτέχνης αδιαφορεί.

Τα περιθώρια στενεύουν, ο κύκλος κλείνει, πρέπει να ολοκληρώσει τη συγγραφή, να αποστείλει τις σελίδες που επεξηγούν και διαφωτίζουν τις σκέψεις του στον Άλφα αναγνώστη (κάποιος άλλος συγγραφέας). Το έσχατο στάδιο: αναζήτηση του κατάλληλου τίτλου. Καταιγιστική απόρριψη κοινότοπων τίτλων που παραπέμπουν σε διάσημα λογοτεχνικά έργα. Η φώτιση έρχεται. Εν εξάλλω, θυμάται αίφνης ότι όλο του το σχέδιο κατέρρευσε εξαιτίας ενός μπαστουνιού που έφερε την υπογραφή του θανόντος και ξεχάστηκε στο αυτοκίνητο. Ο νόμος πλησιάζει, αλλά ετούτο δεν ενδιαφέρει τον καλλιτέχνη. Υπάρχει κάτι σημαντικότερο: το αριστούργημά του δεν είναι τελικά αψεγάδιαστό. Και η αμφιβολία προβάλει για πρώτη φορά. Είναι δυνατόν oi polloi να έχουν δίκιο; Ας είναι, όσος χρόνος απομένει πρέπει να αφιερωθεί ενάντια στην αμφιβολία. Στα γρήγορα γράφει τον μόνο άξιο λόγου τίτλο: Απόγνωση!

Μέχρι τέλους, η ψευδαίσθηση (του δημιουργού, του εγκληματία) κρατάει τα σκήπτρα. Αδυνατεί να διανοηθεί ότι το τέλειο σχέδιό του, το λυσιτελές έργο του, το αρχέτυπο βιβλίο, δεν πρόκειται να δαφνοστεφανωθεί. Ακόμα και την ύστατη στιγμή, στις καταληκτικές σελίδες, όπου ο Νόμος ενσκύπτει αμείλικτα και κόσμος συρρέει έξω από το παράθυρο της μικρής κωμόπολης να απολαύσει τη σύλληψη, ο καλλιτέχνης-εγκληματίας αρνείται τη ζωή και τους αδιάφορους ηθικούς κανόνες και περιορισμούς της: είναι έτοιμος, ως πρωταγωνιστής, διάσημος ηθοποιός της δικής του -πάντα και μόνο- παράστασης να επιχειρήσει έξοδο.

Ποιοι μπορεί να είναι όλοι ετούτοι παρά κομπάρσοι, έτοιμοι να υπακούσουν στα κελεύσματά του, πανέτοιμοι να του προσφέρουν την ποθητή απόδραση; Μα, αναρωτιέται, τι άλλο είναι όλα αυτά αν όχι μια πρόβα; Αυτή την έσχατη στιγμή, η συναίνεσή τους αποτελεί τη μοναδική επιλογή – αδιανόητο να αρνηθούν την έκκλησή του, την εύνοιά του, να μην υπακούσουν στον μεγάλο Δημιουργό: «Αυτό μόνο. Σας ευχαριστώ. Και τώρα βγαίνω».

https://fotiskblog.home.blog/2021/03/... -

Ναι ντάξει κάποια πράματα στον Ν. μπορεί να με απωθούν (σνομπισμός, αλαζονεία κτλ) αλλά είναι μεγάλος συγγραφέας, τι να λέμε τώρα.

-

Vladimir Nabokov is a genius. In Lolita his genius is manifest in the perversion of human sympathies, the seduction of language, the durability of art (yet also the mortality of beauty). In Despair, one of Nabokov's first forays into English prose, there is an early adumbration of what will become the enchanting monster, Humbert Humbert, found in the narrator-murderer Hermann. But aside from the faint outline of what is to come, Despair is a brilliant novel in itself, removed from the nympholeptic successors which follow in the Nabokovian oeuvre. The narrative is a simple one, Hermann happens upon a man whom he believes is his perfect double, and resolves to commit the "perfect murder" - killing his double and cashing in on his own life insurance. But like Humbert, and their mutual progenitor, Hermann is an aesthete: Despair is not merely a novel of mistaken identity, of false doubles, of murder-plot high-jinx, but a novel about art - the reach of art beyond medium into life. Is not the "perfect murder" as much a work of art, of deliberate purpose and imagination, as the "perfect novel" or the "perfect painting"?

To anyone with a passing interest in the masterful Nabokov, his extreme views on literature should be no mystery. He was a combative proponent of "art for art's sake," he believed that the purpose of fiction is to enchant and not to evoke empathy. In his lectures on literature at Wellesley and at Cornell he examined literature as he examined his lepidopteran specimens: with a microscope. Art in fiction, for Nabokov, is the successive accumulation of detail, of a fractal perfection which pervaded through all layers of the narrative and opened a world before the reader which has an almost tactile realism, but which also enchanted, which was fantastic, which was beyond reality, which was art. Hermann represents a perversion of this view on art, for though he seeks the perfection down to the detail, he fails to view with honesty the overall picture. His art is never perfection because while he is a devil for details, he is lost in the greater art of life, which he fails to appreciate.

Throughout Nabokov, we see the butterfly, his passion, as a symbol for the complete cycle of artistic creation. When Lolita is playing tennis, her fleeting poses are beautiful but manifestly useless in the pursuit of victory - a sportsman's manifestation of art for art's sake - and while she plays "an inquisitive butterfly passed, dipping, between us." (This scene parallels the interloping butterfly in the ultimate episode of Pale Fire) The butterfly as a symbol for the ideal art - life imitating art, imitating life, so to speak - coincides with the belief that art is mortality. "Death is the mother of beauty," as Wallace Stevens said, a claim with which Nabokov was sure to agree (note the fateful end of Lolita's titular character). To pervert this belief, to parody his own views on art, Nabokov brings forth Hermann, who sees a beauty in death, in destruction of life (much like Humbert's destruction of Lolita's innocence and life):...what is death, if not a face at peace – its artistic perfection? Life only marred my double; thus a breeze dims the bliss of Narcissus; thus, in the painter’s absence, there comes his pupil and by the superfluous flush of unbidden tints disfigures the portrait painted by the master.

This is a telling insight into the creation of Hermann - the pleasure he sees in death, the reference to Narcissus and to "artistic perfection," are all relevant to the character of Hermann, and significant to the novel's thematic development.

The great irony of Hermann as an artist is his poor consistency with his own dogma. Despite his search for artistic perfection, despite his attention to detail, it is precisely the details which he overlooks, and in doing so gives himself away completely. Rather than devising the perfect murder, he devises the perfect blunder. Not only does he fail to achieve his financial goals, but he ensures his identification as the murderer. He is not a poor bluff, but rather plays cards with his cards face up on the table. The pivotal element, the crux of his entire plan, is the similarity of himself with his victim. He is convinced he has found is perfect Doppelgänger, only to discover that he is the only one who sees any similarity at all. Isn't this the great crisis of artists? The fear that no one will appreciate their art but themselves? For many artists, this is not a hindrance, they create art for themselves - it is a release - it is for it's own sake. Hermann, while having a seemingly genuine appreciation for artistic perfection, prostitutes his artistic efforts for financial gain, and as a result of doing so is doubly foiled.

Despair is not Nabokov's greatest, I cannot argue that. It pales next to florid perfection of Lolita, next to the experimental risks of Pale Fire, and next to the playful game of history and nostalgia, fiction and biography, in Speak, Memory - but it is a great novel, it is worthy of the Nabokovian credit. It is immensely enjoyable to read, as a parodic game on the Crime and Punishment legacy, and also as a mock-treatise on the failures and purposes of art. -

That's it for my seventh Nabokov -- Despair, or Отчаяние, a "far more sonorous howl", as Nabokov writes in the introduction to the work. This represents Nabokov's "first serious attempt to use English for what may be loosely termed an artistic purpose."

The writing is, as you kind of expect from Nabokov, stellar. The story is interesting, and it does not require as much from the reader as some of his other books do -- indeed, Nabokov writes that the book has a "plain structure and pleasing plot." Pretty much true: Hermann Hermann, a man who seems at first to be relatively sane, meets what he believes to be his double (a Dostoevskyian theme, which he in fact ridicules more than anything), and then concocts a pretty stupid plan that, needless to say, fails.

One thing is for certain: Hermann Hermann is a thoroughly distasteful character. A self-serving prick and a thoroughgoing asshole. As he loses his mind and his plans utterly fail, it's hard to feel sorry for him. In fact, you kind of rejoice as the whole thing collapses under his feet. Nabokov portrays the whole thing in such an eerie way that it's hard to move away from the thought that perhaps there is some of Hermann Hermann in Volodya too.

In the introduction Nabokov writes about the similarities between Humbert (of Lolita) and Hermann:

Hermann and Humbert are alike only in the sense that two dragons painted by the same artist at different periods of his life resemble each other. Both are neurotic scoundrels, yet there is a green lane in Paradise where Humbert is permitted to wander at dusk once a year; but Hell shall never parole Hermann.

But, "in kinship with the rest of my books", there is no social comment to be made by Nabokov; there are no Freudian messages to be found in here; this whole thing is not in "the influence of German Impressionists", as Nabokov writes in the introduction, taking stabs at critics of various literary "schools."

It's just a book. Art for art's sake. And the guy is a brilliant writer: read him.

"Although I do not care for the slogan "art for art's sake", there can be no question that what makes a work of fiction safe from larvae and rust is not its social importance but its art, only its art."

- Nabokov -

Un libro assurdo, straziante, divertente.

La perfetta parodia di Delitto e castigo, come suggerisce il protagonista stesso:

“Memorie di un... di un cosa? Non riuscivo a ricordare; e, comunque, Memorie suonava orribilmente fiacco e banale. Ma allora come dovevo intitolare il mio libro? Il sosia? Ma la letteratura russa ne ha già uno. Delitto e bisticcio? Non male...” -

128th book of 2022.

Despair is next as I read all of Nabokov's books in order. This one is Martin Amis's (Nabokov super-fan) second favourite Nabokov novel ever (behind, of course, Lolita). I'm sticking with Updike and calling Nabo's Glory his best Russian novel (so far - I have two left to read). Of all his books, Lolita still reigns supreme, but then I'm yet to read Pale Fire. Anyway, this one flopped when it was first published and apparently earnt Nabokov €40. It's a deliciously wicked, meta, farcical story once again. Hermann Hermann (not Humbert Humbert) is an unreliable narrator who sets out to kill his 'double' to cash on his own life insurance. I'm sure I saw my parents watching a television series with pretty much the same plot recently (within the last year). It's not so simple, of course, and Hermann goes through some troubles. The plot takes a while to get going, Nabokov plays many games. It's riddled with allusions and the whole thing seems to be mocking Dostoyevsky, which makes sense, as Nabokov hated him ('He was a prophet, a claptrap journalist and a slapdash comedian.'). Hermann goes to call this book The Double, but ah! it's taken. Crime and Pun? he wonders. As ever, Nabokov walks a fine line between genius wordplay and devilish games and frustration for the reader. This one was closer to the latter for me, but it's Nabokov, I always find pleasure in reading him. Next up, The Gift (not the Velvet Underground song). -

True confession: I have never read a

Vladimir Nabokov novel until now. A month ago the only one of his novels that I could name was Lolita. While I’m sure it is a good book (165,000 GR readers can’t all be wrong), books with pedophiles as main characters don’t usually make it to the top of my TBR list so I was interested in finding another Nabokov book that would give me a taste of this renowned author’s style.

Enter Despair.

The title of this novel is deceiving. One would expect that a novel named Despair would be depressing book full of gloom and doom, a tale about sad and hopeless people. Who needs a novel about that? As we are already assured of getting all that and more from November’s election, there is no need to get one’s despair from fiction.

Fortunately, Despair is not like that. Written in the 1930s in Russian and subsequently translated to English, Despair is the quintessential unreliable narrator story. Hermann, an unsuccessful businessman with dreams of becoming a successful writer, encounters a vagrant who could be Hermann’s twin and concocts the ‘perfect’ crime, intent on creating a literary masterpiece by chronicling his crime."Oh, Conan Doyle! What an opportunity you missed! For you could have written one last tale concluding the whole Sherlock Holmes epic; the murderer in that tale should have turned out to be … the very chronicler of the crime stories, Dr. Watson himself. A staggering surprise for the reader."

Conan Doyle isn’t the only author Hermann aspires to. He mentions another Russian novelist more than once, referring to ‘

old Dusty’ and his ‘great book,

Crime and Slime’.

When it comes down to it, Hermann’s crime is neither perfect nor original. What does make the story unique is Nabokov’s story-within-a-story approach, writing as Hermann writing his criminal masterpiece. This in itself makes Despair a classic work of crime fiction. I recommend it highly.

FYI: On a 5-point scale I assign stars based on my assessment of what the book needs in the way of improvements:

*5 Stars – Nothing at all. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

*4 Stars – It could stand for a few tweaks here and there but it’s pretty good as it is.

*3 Stars – A solid C grade. Some serious rewriting would be needed in order for this book to be considered great or memorable.

*2 Stars – This book needs a lot of work. A good start would be to change the plot, the character development, the writing style and the ending.

*1 Star - The only thing that would improve this book is a good bonfire. -

Ожидания: роман Таны Френч «Сходство»

Реальность: роман Набокова «Отчаяние»

Действительно, только так и могла развернуться любая история с двойником, какие существуют на самом деле только в сознании зацикленных на своих щеках и носах, тонущих в литературщине дешевых коммерсантов.

Безупречно, конечно же. -

Despair (Russian: Otchayanie)

Author: Vladimir Nabokov

Read: 8/7/20

Rating: 4.5/5

Poem Review. Pleiades poems have a single word title, followed by a single 7-line stanza. The only requirement is that the first word in each line must begin with the same letter as the title.

**** Spoilers ****

"Dis-pair"

Despite a nonlinear plot and a conversational narrative style prone to digressions and rambling,

Despicable narrator has a beguiling personality that readers can't help but be captivated by.

Duplicity takes multiple forms- from Hermann's cunning schemes victimizing Felix to ultimately falling victim to his own

Delusional mental state, entertainingly manifested in his

Delirious thoughts as he proudly confesses to his reader.

Deftly written with scintillating humour, clever plot twists, and a masterfully paced layer-by-layer revealing of truths-

Deceptive in its slimness, this novel rivals Nabokov's renown "Lolita" in its genius!

Title Meaning: Ostensibly, Hermann rashly titles his memoir "Despair" as he awaits his dismal fate with authorities. Ah, but Nabokov is much too clever to leave it at that. A hugely talented man, Nabokov knew three languages: English, French, and Russian. And in French, "des pairs" means "pairs" or "peers". It can also be construed as "dis-pair", probably referring to the unreliability of Hermann's conviction that Felix is his double. No one else sees it, after all.

#PleiadesPoem #ReviewPoem #artistlife #classicliterature #conartistry #confessional #cousins #meta #mirror #Russian #pagetoscreen #perfectmurder #socialclass #streamofconsciousness #translated #unreliablenarrator -

I hate Nabokov. He's a bleedin' megalomaniac interested in nothing other than proclaiming the invention of paper and ink as an exclusive gift to himself.

I take deep breaths of exasperation reading every fourth sentence this guy writes. What, can he just go on playing with my feelings? As if he's never gonna call back? He's not, is he?

Despair was just such a declaration. Fool tries to fool people, and you say, "Ah! This is his first book. It'll show his immaturity and I'll not have to gasp in pain every time I hear his name."

But oh no. In the last two pages, he gives you enough shock as to arm you with a knife you would drive through him right after you have finished rethinking the entire book and telling yourself, "Damn! I'm the one who got fooled."

Shame on you, Nabokov. I gave you the wrong number anyway. -

Zaboravljate, dragi moj, da umjetnik, prije svega, zapaža razliku između stvari. Prostaci zapažaju svoje sličnosti.

Očajanje je jedna od onih priča koje su stopljenje u predvorju onoga što zovemo na ivici između života i smrti, trenutnog uzbuđenja i srozavanja. Ovo je neka vrsta autobiografskog romana, fikcije, a pri samom kraju on skoro postaje dnevnik. Nabokov se poigrava sam sa sobom, a time i sa čitaocima. Kada napiše (počesto je to radio) "dragi moj čitaoče" ja sam se neprestano kezio. Ne zato što je to iritantno ili što nekoga može dovesti do tačke pucanja, već to njegovo ponavljajuće "dragi moj čitaoče" zatomi sav gnjev čitaoca, preovlada ga i čini ga budnim. Za Nabokovljevu igru vrlo je važno ostati budan. Po samom naslovu knjige sam i očekivao da će to biti jednostavno čitanje. Jer šta naslov "Očajanje" može da pruži sem nezgrapnu situaciju glavnog junaka, blijedu sjenku njegovog postojanja, njegovo mentalno previranje i na kraju pokušaj gracioznog podviga. Takva sjenka gleda u njega i on u nju i nijedno ni drugo ne mogu da se spoznaju. Nabokov sve to čini na referencu Dostojevskog, a spominjao je i Portret umjetnika u mladosti, samo malo u parodičnijem kontekstu.

Njegov Herman pronalazi svoju odraženost u Feliksu koga upoznaje u Češkoj. Feliks je siromašan i sušta je suprotnost Hermanu, ili barem materijalno. Od njihovog upoznavnja sve će krenuti drugačije. Ne samo za Hermana već i za samog Feliksa. Ovdje će se desiti metamorfoza, ali ona će se pokazati kao puka suludost, prosto, to će biti samo igra. Narator pravi paralelu sa primjesom humora na "Zločin i kazna" od Dostojevskog i pokušava da napravi savršen zločin. To treba da se desi na umjetnički način. Nabokov je presmiješan i to zaista izgleda vrlo zanimljivo. Naravno, uvijek je potrebno stvoriti povod za sam zločin. To je lako pogoditi jer uvijek je novac u pitanju. Nije li Raskoljnikov ukopao dvije babe isto radi novca? Zanimljivo je kako taj običan papir bez ikakve vrijednosti to jest on čini druge stvari vrijednim, zapravo igra ulogu posrednika između same žrtve i ubice. Kao da je taj posrednik vrlo moćan i nikako da se obuzda. Je li postoje okovi za njega? Kakva samo drskost da nešto što je bezvrijedno čini druge stvari vrijednim. Hoće li neko nekoga ubiti zato što nije napravio dobar ručak? Ili što nije oprao ruke pri rukovanju? Ne, to će se desiti samo zbog onog bezvrijednog. Takva spoznaja upravo ovaj roman čini humoričnijim. Herman je malo tupav. Možda da nije gledao samo Feliksovu spoljašnost već upoznao njegove unutrašnje puteve i prošlosti, jasno iskristalisao njegovu dušu - ne bi morao da gradi podvig koji vodi savršenom zločinu. Možda bi mu u toj duši bilo zanimljivo. Ali on svog dvojnika nije dovoljno upoznao i krenuo je ka ostvarivanju svog cilja - udvostručavanja isplate osiguranja nakon počinjenog zločina.

Dragi moj čitaoče ko je Herman, a ko Feliks to ti moraš da saznaš. Ko je ubica, a ko žrtva to ti takođe moraš da saznaš. Da li se uopšte zločin desio, čitaoče, to treba tek da saznaš. Šta se desilo sa Hermanom, a šta sa Feliksom saznaj čitaoče. Dragi čitaoče dok budeš čitao Očajanje ja ću ti se potanko smijati. Ali dragi čitaoče, smijaćeš se i ti. -

Нужно сразу признаться, что я отношу себя к тем, кто не любит Набокова. Главный герой Герман Карлович своим эгоцентризмом, нарциссическим самолюбованием "сложными чертами лица", убежденностью в своем необыкновенном уме вызывает аллергическое раздражение, буквально на грани отторжения. Иногда кажется, что Набоков описывает себя: "Если бы я не был совершенно уверен в своей писательской силе, в чудной своей способности выражать с предельным изяществом и живостью – Так, примерно, я полагал начать свою повесть. "

То, что Феликс и Герман нисколько не похожи, автор несколько раз подчеркивает заранее: лакей, принесший пиво, не замечает ничего особенного, Феликс тоже не находит сходства. Непонятно, каким видом ментального заболевания страдал Герман, если не заметил несхожести.

В стремлении подчеркнуть мещанство героев, Набоков перестарался, раздражает, что Лидия причесывает волосы грязнейшей Ардальоновой щеткой, ее чулки. Также инцест вызывает пренеприятнейшее чувство.

В чем художественный смысл романа? С одной стороны, мы видим критику мещанства, скрытой за детективной фабулой. Но зачем нужно было делать это преступление таким смехотворно глупым? Сила высмеивания мещанства снижается, когда мы имеем дело с ментально нездоровым человеком. Это во-первых. А во-вторых, роман превращается в трагикомедию, фарс - безумец возомнил о своей схожести с совершенно непохожим человеком и убил его ради страховки. Все кроме него самого видят несходство. Акценты смещаются.

Тоска Набокова по своему имению в оставленной, охваченной революцией России, выпирает во всех произведениях, именно тоска по имению, саду, богатству, сожаление об их утрате. Не по родине.

Для меня остался непонятным, какую идею хотел писатель донести до нас - неужели, чтобы нарисовать карикатуру на "Преступление и наказание", сделав это исподтишка, прикрываясь безумством главного героя? -

Seriously, I didn't like this. Yeah, I like how

Vladimir Nabokov writes but this book just doesn't have the sparkle, the humor or the polished writing of

Lolita or

Speak, Memory or other books by the author. It feels like a piece that still needs more work….or maybe you can work something to death. Look at the history of this book.

Despair first came out in 1934 as a serial in the Russian literary journal Sovremennye. It was published as a book in 1936, translated by the author into English in 1937, but what exists today is the author's reworking of 1965. Clearly he did have time to rethink this.

Why doesn’t it work for me?

Despair not only was a forerunner to

Lolita, published in 1955, but it feels like that too. One can compare Hermann of this novel with Lolita's Humbert Humbert. Both are unreliable first-person narrators, but one is a shadow of the other. Not in who they are but in the strength of their characterizations. Lydia, Hermann's wife, doesn't come close to

Lolita's Dolores.

So what is the theme of this one? It is a murder story, but more! It is really about doubles, about identity and what connects one person to another. Hermann is delusional. Anything he says has to be questioned. Of course that is true too of Humbert Humbert, but there it is easier to just see the facts presented as his point of view. In

Despair the story is so much more complicated; you are thrown between the writing of a story, how authors write stories and what actually happens, i.e. the events of the tale. Too complicated! Not properly thought through. Similar themes but quite simply not as good.

There are also funnier and more noteworthy lines in

Lolita. More to chuckle at. More to think about on all sorts of themes, having nothing to do with sex or murder.

Christopher Lane does a good job with the narration, even if occasionally when he personifies dubious characters of Russian origin it was practically impossible to hear the lines. Arrogance, self-satisfaction and delusional traits, as well as furious explosions of temper all are well intoned.

For me this was quite simple a forerunner to

Lolita. That I gave five stars. -

Re-visit 2016 is the film recommended by Karen.

Plotline: The narrator and protagonist of the story, Hermann Karlovich, a Russian of German descent and owner of a chocolate factory, meets a homeless man in the city of Prague, whom he believes is his doppelgänger. Even though Felix, the supposed doppelgänger, is seemingly unaware of their resemblance, Hermann insists that their likeness is most striking. Hermann is married to Lydia, a sometimes silly and forgetful wife (according to Hermann) who has a cousin named Ardalion. It is heavily hinted that Lydia and Ardalion are, in fact, lovers, although Hermann continually stresses how much Lydia loves him. On one occasion Hermann actually walks in on the pair, naked, but Hermann appears to be completely oblivious of the situation, perhaps deliberately so. After some time, Hermann shares with Felix a plan for both of them to profit off their shared likeness by having Felix briefly pretend to be Hermann. But after Felix is disguised as Hermann, Hermann kills Felix in order to collect the insurance money on Hermann on March 9. Hermann considers the presumably perfect murder plot to be a work of art rather than a scheme to gain money. But as it turns out, there is no resemblance whatsoever between the two men, the murder is not 'perfect', and the murderer is about to be captured by the police in a small hotel in France, where he is hiding. Hermann who is writing the narrative switches to a diary mode at the very end just before his captivity, the last entry is on April 1.

Fraudio: Read (brilliantly) by Christopher Lane

From wiki: originally published as a serial in the politicized literary journal Sovremennye zapiski during 1934. It was then published as a book in 1936, and translated to English by the author in 1937. Most copies of the 1937 English edition were destroyed by German bombs during World War II; only a few copies remain. Nabokov published a second English translation in 1965; this is now the only English translation in print.

narrator: Hermann Karlovich

his wife: Lydia

his business: chocolate

doppelgänger: Felix

setting: Prague

musical backdrop:

Tango in Prague - Milonga Prague Castle

5* Pale Fire

4* Sebastian Knight

3* Lolita

3* The Eye

3* Despair

2* Transparent Things -

Двойнственост и илюзии

Ще запомня таз�� книга с начинът, по който си играеше с представите ми за двойнственост -когато два обекта, две идеологии, две личности (и т.н.) споделят значителни прилики, но принадлежат към различни социални класи заради името си, опаковката си или някой друг дребен външен признак, какво говори това за света, в който живеем?

Описания

Като читател много се дразня, когато авторът ми пробутва описания за пълнеж. Досега нямах ясна концепция как точно преценявам кога едно описание е пълнеж и кога не. "Отчаяние" съдържа отговорът на този въпрос. Описанията са страхотни - описания на вятър, тесни улици, електрически стълбове. Това, което ги постави на място бяха специалното им място в паметта на героя. Който е чел Набоков, знае специалното му отношение и интерес към човешката памет. Описанията в "Отчаяние" са плътно прикрепени към разказа на историята и без тях би се изгубил значителен обем от информация за личността към ненадеждния разказвач. Още по-вълнуващо е, че Набоков налага неговият начин да работи с описанията, подигравайки точно това, което аз също ненавиждам - самоцелното им използване. И още по-по-вълнуващото е, че го споделя директно на читателя посредством ненадеждния си разказвач. Няма как да не заобичам тази творба.

Експериментът

Набоков вкара поне няколко техники на разказване - директни обръщения към читателя, навлизане в личносто пространство на читателя, още по-деликатно излизане от читателската територия и плавно гмуркане обратно в историята; епистоларна форма на разказване; дневник; сценарийно представяне на определени сцени, които винаги бяха въвеждани с "Междувременно в...". Отово с цел пародиране на самоцелното използване на техники. Няма да споменавам, че този експеримент беше повече от успешен. Това ми остави усещането за много близък допир с разказвача, което беше страшно и зловещо, защото Герман е личност, изтъкана от скрити/потиснати мисли и пориви от човешката природа, присъщи за идеите на Шекспир. Извървяването на 140 страници с него в този смисъл едва ли ще понесе на всеки.

Страхотна среща с Набоков. Страхотна игра на писателя гений с мислите на читателя. Истинско произведение на изкуството.

Обичам да чета книгите на Набоков. Той се чете до безкрай. Всеки път ти говори нови неща, а уж четеш същите букви. -

Specchi e maschere, il tema del sosia interpretato da un personaggio, Hermann Hermann, non proprio gradevole, vanesio e ridicolo.

Il suo incontro con Felix, identico a lui (o è solo un’illusione) mette in moto una serie di piani per sparire e rifarsi una vita, in un racconto che usa i toni del thriller e gioca col lettore. -

Thoughts forthcoming; for now, yes! An amazing novel. I have a feeling it will take a while for me to go over it in my head, so stay tuned.

-

Τρίτο βιβλίο του Ναμπόκοφ που διαβάζω Στο συγκεκριμένο κατάλαβα πλέον ξεκάθαρα τι μαέστρος είναι στο να χειρίζεται τον αναγνώστη. Απλά υποκλίνομαι!

-

I have not read Nabokov for quite a while. The writing is so unlike most other writing with long periods of complete existential genius. There are times where it becomes too clever and divergent just to showcase Nabokov's writing talent (I feel) which, I don't blame him and, which, provided flashes of utter brilliance.

At the beginning of the novel, I felt a more linear narrative would have reined in some of the unwieldy flights of fancy but towards the end I realised that the disjointed (understatement!) narrative is there to begin to confuse and distract your own mental state in parallel with the narrator's. The twist/s were not unexpected, and I think they are meant to be obvious, but that does not spoil the outcome as by the conclusion you become more absorbed in the narrator's reaction to events rather than the events themselves.