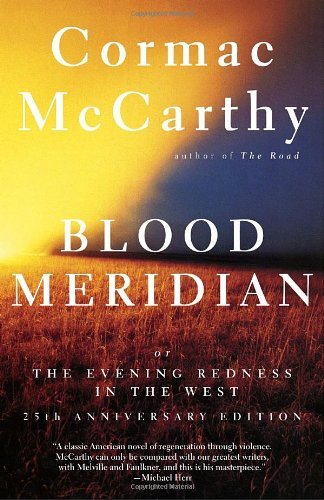

| Title | : | Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | - |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 351 |

| Publication | : | First published April 28, 1985 |

Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West Reviews

-

The man finished the book. He closed the pages tightly together then put one foot on the floor then the other then used his hands to push himself up out of the chair and then put one foot in front of the other until he had walked all the way to the book shelf and then put the book on the book shelf. The deer walked in. The man whirled around and fired once with his pistol and the brains of the deer went flying out the back of its head and painted the wall a color dark red like blood. The man sat down again like a man sitting down.

I didn't really like the book, said the dead deer.

I reckon I was pretty conflicted, replied the man grimly.

His writing style is pretty problematic.

I reckon his style is perty silly, he just strings a bunch of them declarative statements together, like 'the man did this then the man did that etc", but they don't paint no picture, they're done totally unevocative of anything. I reckon it don't take no skill to just state in excessive detail what someone is doing. It takes artistic skill to say it in a way that done bring it to life for the reader, and he don't done really do that. I reckon it's some sub-Hemingway shit he's doing.

It's not all bad though.

I reckon some some of the images t'were pretty powerful.

And the judge is a memorable character.

I reckon he's the only one though. All the rest of them there charac'ers ain't real memorable, like he done put no effort into 'em 'cause he spent all his time on the judge. And that there whole novel was all...whatdjacallit, structureless and stuff. And real repetitiv' too.

I read that he doesn't see why people like Proust and James because he thinks all novels should be about life and death things.

I reckon that's 'cause he's too obsessed with subject matter and not enough with style and art.

The dead deer nodded and walked out. The man slowly got up again by putting one foot then the other on the floor and then used his hands to push himself up out of the chair. He fixed himself a drink and resolved not to take anymore book recommendations from Harold Bloom. -

Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian is unquestionably the most violent novel I’ve ever read. It’s also one of the best.

For those who would consider that a turn-off, I offer this caveat:

For the overwhelming majority of fiction that involves a lot of violence, the violence itself is an act of masturbation representing either the author’s dark impulse or, perhaps worse, pandering to the reader’s similar revenge fantasies (this might explain why the majority of Blood Meridian fans I know personally are men, where as the majority of those who’ve told me they were unable to finish it are women).

Don’t get me wrong, the violence in Blood Meridian is gratuitous. It’s both mentally and emotionally exhausting, even in a day and age where television and movies have numbed us to such things. But unlike, say, the movie 300, the violence serves a purpose – in fact the gratuitousness itself serves a purpose. Like how the long, drawn out bulk of Moby Dick exists to make the reader feel the numbingly eventless life of a whaling vessel before it reaches its climactic destination (McCarthy is frequently compared to Melville, btw), Blood Meridian exists to break the reader’s spirit. Like the mercenaries the narrative follows, the nonstop onslaught of cruelty after cruelty makes us jaded. The story brings us to what we think is a peak of inhumanity that seems impossible to exceed, and just as we stop to lick our wounds, an even more perverse cruelty emerges. The bile that reaches the tip of our tongue at reading of a tree strewn with dead infants hung by their jaws at the beginning of the book (a scene often sited to me as the point many readers stop) becomes almost a casual passiveness when a character is beheaded later on. We become one of these dead-eyed cowboys riding into town covered head-to-toe in dried blood and gristle.

The story is based on My Confession, the questionably authentic autobiography of Civil War Commander Samuel Chamberlain, which recounts his youth with the notorious Glanton Gang – a group of American mercenaries hired by the Mexican government to slaughter Native Americans. Whether or not Chamberlain’s tale is true only adds to the mythic quality – exemplified by the character of Judge Holden.

Blood Meridian is really The Judge’s story. He is larger than life. Over seven feet tall, corpulent, hairless, albino, described as having an infant-like face and preternaturally intelligent. He is a murderer, child killer, pedophile and genocidal sociopath. But the question that plagues anyone who reads the book is – who is he really?

The easiest conclusion is that he is the devil, or some other demon. His joyous evil and fiddle-playing are enough clues to come to that, but more controversial (and less popular) is the idea that he is actually the wrathful God of an uncaring universe. He’s called THE Judge, after all.

He spends a great deal of time illustrating new discoveries – be it an Indian vase or petroglyph – only to destroy it when finished. It’s commented that he seems intent on “cataloging all creation”. When a fellow mercenary asks why he does it, he smiles and cryptically replies “That which exists without my knowledge exists without my consent.”

The fact that the book is rife with biblical imagery implies that he is more than a mere symbol of man’s inhumanity to man (which is not to say that the devil isn’t), but when the book ends ( SPOILER ALERT) and our protagonist’s body is found shoved into a commode, the townsfolk stand staring into the darkened doorway of the latrine, eerily mirroring the apostles staring into empty crypt after the resurrection. But here, there is no ascension; no salvation offered. Only the Judge, who dances to the closing lines, “He is dancing, dancing. He says that he will never die." -

Spilled...emptied...wrung out…soul-ripped...that pretty accurately sums up my emotional composition after finishing this singular work of art. Ironically, I’m sure I only absorbed about 10% of the “message” McCarthy was conveying in this epic exposition on war, violence and man’s affinity for both. Still, even with my imperfect comprehension, I was shaken enough by the experience that, though I finished the book days ago, I’m just now at the point where I can revisit the jumble in my head enough to sort through how I feel.

One feeling I have is that Cormac McCarthy is word-smithing sorcerer and a genius of devious subversion. He's taken the most romanticized genre in American literature, the Western, and savagely torn off its leathery, sun-weathered skin in aid of showing an unflinching, unparalleled depiction of man at his most brutal and most violent.

This is man as “world-devourer.”

Oddly enough, in subverting the Western motif, McCarthy may have written its ultimate example. I tend to agree with Harold Bloom’s assessment when he says, “It culminates all the aesthetic potential that Western fiction can have. I don’t think that anyone can hope to improve on it… it essentially closes out the tradition.” Well said, Mr. Bloom.

PLOT SUMMARY/CHARACTERS:

Based, at least partially, on real life events, the story is set around 1850, immediately after the end of the Mexican-American War, and takes place in the “borderlands” between the two countries that stretches from Texas to California. The narrative follows a young teenager, known only as “the kid,” who runs away from his father in Tennessee after his mother dies.See the child… He can neither read nor write and in him broods already a taste for mindless violence. All history present in that visage, the child the father of the man.

After engaging in a number of notably violent occupations (including bison hunter/skinner and as a soldier in an “irregular” army borderland goon squad), the kid eventually hooks up with a group of scalphunters led by John Glanton (historically known as the Glanton Gang). The rest of the story follows the kid and his exploits with the Glanton Gang as they cut a swatch of violence across the borderlands that is unlike anything you are likely to have read about before.

However, the narrative of the kid and the Glanton Gang are simply there to give McCarthy’s story a framework to work through, a context. This is not a novel about the history of the borderlands or the atrocities that were committed there. That is incidental to its purpose. McCarthy uses the lawlessness and extreme carnage of the period and the horrific events that transpire as a microcosm to explore the nature of war, violence and man’s unrivaled capacity for unmitigated depravity.

Not a beautiful subject…but soooooooo beautifully done.

This brings me to Judge Holden (aka “the Judge”), one of the most memorable literary figures I have ever come across. He's also among the most amoral, depraved, sadistic, and remorselessly cruel individuals I have encountered in my reading. In the character of the Judge, McCarthy has distilled and personified the ultimate expression of war and violence. He is a manifestation of pure evil, a spokesman for the belief that war is man’s calling and his purest state is to be an instrument for violence. Fun guy huh?

The Judge's philosophy is that "War is god," man’s purpose is to be its ultimate practitioner and any attempts to civilize or reform this aspect of man are doomed to failure. “Moral law is an invention of mankind for the disenfranchisement of the powerful in favor of the weak. Historical law subverts it at every turn.” He preaches that only by embracing and celebrating man’s capacity for violence can man attain his true potential.If God meant to interfere in the degeneracy of mankind would he not have done so by now? Wolves cull themselves, man. What other creature could? And is the race of man not more predacious yet? … This you see here, these ruins wondered at by tribes of savages, do you not think that this will be again? Aye. And again. With other people, with other sons.

The Judge is described as huge, completely hairless and very pale. He speaks multiple languages, is well-versed in classic literature and has extensive knowledge of many of the natural sciences. Throughout the story, the Judge is shown as almost “otherworldly.” He is depicted accomplishing seemingly miraculous deeds and having “special” insight into events. He appears not to age despite being seen over a span of 30+ years. In addition, everyone who rides with him recalls “seeing the Judge” earlier in their life (and always at a time of great violence).

I came to see him as the “Muse of War and Violence.” Here is a great description from the end of the book where the kid muses on where the Judge came from:A great shambling mutant, silent and serene. Whatever his antecedents, he was something wholly other than their sum, nor was there system by which to divide him back into his origins for he would not go. Whoever would seek out his history through what unraveling of loins and ledgerbooks must stand at last darkened and dumb at the shore of a void without terminus or origin and whatever science he might bring to bear upon the dusty primal matter blowing down out of the millennia will discover no trace of ultimate atavistic egg by which to reckon his commencing.

Whatever the Judge’s true nature, he is singularly compelling.

THE WRITING:

One quality of McCarthy’s writing that amazes me is that it is both fire and ice for the soul. His unique style combines both (i) sparse, but deeply layered prose similar to Hemingway (i.e., short, seemingly straight-forward sentences that upon further inspection can mulch up your insides) with (ii) flowery “image heavy” descriptions that are almost Shakespearean in their melodrama. The combination can be devastating and it's why I am so sure I only absorbed a fraction of what McCarthy was saying on the first read.

Almost every sentence, if you go back and re-read it can be chewed more slowly to increase the amount the amount meaning and flavor released. This is the kind of book I think you should read once and then subsequently re-read a chapter at a time over a much longer period. At least that was my impression.

Much of Blood Meridian is written from a dream-like yet “hyper alert” state of consciousness. No, not dream-like, more like nightmarish as McCarthy constantly transforms the settings into aspects that call to mind classical visions of hell. Here are a just a few quick examples I picked out:They rode through a region where iron will not rust nor tin varnish. The ribbed frames of dead cattle under their patches of dried hide lay like the ruins of primitive boats upturned upon that shoreless void and they passed lurid and austere the black and desiccated shapes of horses and mules that travelers had stood afoot. These parched beasts had died with their necks stretched in agony in the sand and now upright and blind and lurching askew with scraps of blackened leather from the fretwork of their ribs they leaned with their long mouths howling after the endless tandem suns that passed above them. The riders rode on.

I love that last sentence, “The riders road on.” It’s just so Hemingway. Here’s another:On the day following they crossed the malpais afoot, leading the horses upon a lakebed of lava all cracked and reddish black like a pan of dried blood, threading those badlands of dark amber glass like the remnants of some dim legion scrabbling up out of a land accursed, shouldering the little cart over the rifts and ledges, the idiot clinging to the bars and calling hoarsely after the sun like some queer unruly god abducted from a race of degenerates.

CONCLUSION:

In sum, a truly sublime experience. After reading

No Country for Old Men, I was not sure that McCarthy would ever be able to floor me like he did in that book. I was mistaken. Round two with McCarthy has found me once again knocked to the canvas with my brain reeling. I'd be hard-pressed to choose a winner between the two, but this one definitely has become the newest addition to my list of all time favorites.

6.0 stars. HIGHEST POSSIBLE RECOMMENDATION!!!

-

Breathless. Unique. Brutal. There are many words that could be used to describe Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy. For me, this was my second time through and I liked it far better than my first reading. Judge Holden, John Job Glanton, Toadvine, and the "kid" are all fantastic characters. I shudder to think that the horrors visited upon the Indians and Mexicans and homesteaders were all based on fact. The apocalypse described in The Road is not too far a cry from the hellish country on the US-Mexico border (which has not really changed if we exchange the scalper mercenaries for the drug cartels) and yet the descriptions and language of Blood Meridian is more beautiful to me. The symbolism here is quite strong and one wonders whether the author is a nihilist like his characters or if there is really some redeeming quality buried deep inside man...a true American masterpiece.

I would read The Border Trilogy after finishing Blood Meridien. I have not tried Suttree or Child of God, but they would have a hard time to top this one! -

After reading Blood Meridian, I may never view a western film the same way again.

To be certain, it is a masterpiece, a rare and unique work of literature that rises above classification and genre. And to be certain, McCarthy must be viewed as a great American writer, one of the greatest in our time.

That having been said, this book is not for everyone; it is painfully brutal, violent at it's heart. McCarthy's primitive writing style emphasizes this primal, bloody landscape like a Jonathon Edwards sermon. Glanton and Judge Holden, based upon actual persons, have been written as archetypal villains. The Judge may be a composite of Mephistopheles and Conrad's Mr. Kurtz, and perhaps even Richard III.

Strong, powerful book.

-

There are two ways to evaluate a book, as far as my unlearned mind can concoct at the moment. Stylish literary flourishes sometimes cloud our judgment when it comes to evaluating the plot itself, which is, after all, the reason why the book exists.

This book is well written. If I'm a 11th grader, and I need to do a book report, I'm drooling over the blatant symbolism dripping from each page. The scene is set admirably, though the repetitive nature of our brave hero's wanderings (at least it's with symbolic reason) lead to a paucity in novel adjectives by the 13th desert crossing. There are only so many ways one can say that it's hot, dry and empty. And dry. Boy, that sun sure is strong. I'm there, I'm with you, all right, it sucks around here, phew, the sun's really beating down today. And there are a lot of bones. Dead things abound, OK, I get it.

Then there's the story line. Explain to me again why I'm interested in the wanton marauding of a band of depraved demons? So, we enjoy the dashing of infants into rocks because of the supposed literary merits of the work? We can bash/splatter/expose brains of whatever, happen upon crucified corpses, and ignore any modicum of human decency because the book is about something deeper? But, you say (and without quotes you say it), that's what it was like. Oh yeah? It was like that? Says who? Why do you want to believe that it was like that? As bad as humankind is, our reality is not that despicable, though our souls may be. Why do we have to play follow the leader behind our impish pied piper, pretending an enlightened understanding of some grandiose truth, while all we really do is sate our own personal blood lusts? I wonder.

By the way, if neglecting quotation marks somehow makes the book classier, why not just go all out and remove spaces between words. You better believe I won't be speed reading the repetitive descriptions of how tired everyone is if there aren't any spaces. Why stop there, periods are for two bit hacks too. You're not a real author until you slaughter a few hundred non-innocents (nay, no one is innocent) while neglecting a basic courtesy to the reader.

Who knows, I don't speak Spanish, maybe I'm just missing the point entirely. How do you say "flayed skin" in Spanish? -

This is Jane Austen antimatter.

Trying to convey how this was so different to anything I've ever read, it occurred to me that it was like a huge black vortex that would suck early nineteenth century marriage plot novels into the void. It's the complete obverse of sweet girlie stuff: no lurve, no irony (I wonder if Cormac McCarthy has a humour mode? If he does, he certainly wasn't in it writing this), no insightful self-discovery or examination of the human heart. No, this is bleak and bloody, gory and grisly, there are bludgeonings and beheadings, shootings and stabbings and skewerings and scalpings, and piles and piles and piles of corpses - as a film, I wouldn't have been able to stand it. How could I stand it here? Well, it was usually over pretty quickly. He doesn't dwell long and lovingly on every detail: radical and dramatic images burn on the mind's eye, but no prurient poking and puddling. Nasty, brutish and short. Stomach churning, but not for too long.

Then there is little in the way of plot. Characters? Bad, worse, or imbecile. So what pleasures does it afford, pleasures that can compensate for the horror? Or is it the horror that becomes pleasurable? Yes, that is the worrying thing - obviously the language is a wonder and can make up for much, but there is a very troubling phenomenon. The reader begins to take on the reasoning of the charismatic, satanic Judge Holden: this is a game in which the stake is life itself. There is only life or death, nothing else. And the Glanton gang is so evil that we can take joy in their annihilation, and the kid is the only one who has shown the slightest faint scruple when it came to slaughtering, so we hope for his survival and follow keenly his fight for life. And did I mention the language? Majestic, portentous, weighty, reminiscent of Milton and Blake and the Bible. Sparse, terse dialogue. Sumptuous description. A fearless novel that shocks and troubles, especially when you realise that this is based on real events on the Texas borderlands in 1848-51. "... and not again in all the world's turning will there be terrains so wild and barbarous to try whether the stuff of creation may be shaped to man's will or whether his own heart is not another kind of clay." -

Cormac McCarthy's west of absolutes is a wonder to behold. Villainous attacks on people devoid a home, desecration of the westland, listings of all things in the majestic, transitory landscape like observations by Darwin at the Galapagos in lush (sometimes horrific) detail, murky human psyches, no dialogue, and especially that campfire philosophy by which anyone can find some sort of meaning in their modern lives (especially if you're fortunate enough to inhabit the places which Mr. McCarthy describes!)... are all the ingredients of a McCarthy book & the way this one is polished, symbolic & graphic makes it my favorite McCarthy book by far.

The apocalyptic landscape of "The Road" is here, but it's thankfully not as literal as that novel about human annihilation after cataclysm. If you were shocked by the cannibals eating babies in that one... well, you ain't seen nothin'. This ultraviolent account is well researched, well versed, poetic. The "Blood Meridian" and the act of scalping are one: you simply lose most of your head as you look at the very promise the west has (had) to offer. My favorite line: "A lamb lost in the mountains cries. Sometimes comes the mother. Sometimes comes the wolf..."

Lawlessness and betrayal reigns supreme. Apache attacks & famine are omnipresent; & it is this blood-thirst that shocks the reader and at once impels him to continue reading to see what befalls the group of barbarians & sinners next. -

Brutal and Poetic at the same time...Just changed it to a five star, what the h...... This book is monumental.

Seems like a contradiction, brutal and poetic, but somehow it works.

The story is bleak, dark, bloody but also filled with beautiful descriptions of the countryside, the desert, the people in the book. The colorful Judge is some character.

Tough book, not sure I took it all in and had to take some breaks during the read.... but hey, it's Cormac McCarthy...a grand writer he is.

It was evening of the following day when they entered San Diego. The expriest turned off to find them a doctor but the kid wandered on through the raw mud streets and out pas the houses of hide in their rows and across the gravel strand to the beach... Loose strands of ambercolored kelp lay in a rubbery wrack at the tideline. A dead seal. Beyond the inner bay part of a reef in a thin line like something foundered there on which the sea was teething. He squatted in the sand and watched the sun on the hammered face of the water. Out there island clouds emplaned upon a salmon colored othersea. Seafowl in silhouette. Downshore the dull surf boomed. There was a horse standing there staring out upon the darkening waters and a young colt that cavorted and trotted off and came back....

Based on historical events that took place on the Texas-Mexico border in the 1850s, we follow and witness the grim and bloody coming of age of the Kid, a fourteen-year-old Tennessean who stumbles into a nightmarish world where Indians are murdered and the market for scalps is thriving...

They rode on and the sun in the east flushed pale streaks of light and then a deeper run of color like blood seeping up in sudden reaches flaring planewise and where the earth drained up into the sky at the edge of creation the top of the sun rose out of nothing like the head of a great read phallus until it cleared the unseen rim and sat squat and pulsing and malevolent behind them. The shadows of the smallest stones lay like pencil lines across the sand and the shapes of the men and their mounts advanced elongate before them like strands of the night from which they'd ridden, like tentacles to bind them to the darkness yet to come. They rode with their heads down, faceless under their hats, like an army asleep on the march. By midmorning another man had died and they lifted him from the wagon where he'd stained the sacks he'd lain among and buried him also and road on.... -

The Power of a Book

Sometimes the power of a book is how horrible it makes you feel. I had put this book down twice. I just could not make friends with it, yet, it was a McCarthy book and the lyrical writing in it was far better than his other books, except to say for, The Road, which I have read twice. I will read this one again someday.

McCarthy can be very hard to read, at least for me. The violence in some of his books is over the top. It isn't that he takes you step by step into it, he doesn't describe much. It is the characters, their cruelty, their sociopathic behavior. There are no emotions in this book, except for those that you wish to give it. I would not be reading him if it were not for his poetry, his lyricla way of writing. No one can write as well.

The third time I picked up this book I told myself to just read it. I finished it.

Someone wrote that there is a Yale professor that put the book down twice and finally finished it. He now teaches it in his classroom. Perhaps he was the person that said that this was the most evil book written. I don't believe so. I know of a book that is much more evil.

NOTE Harold Bloom is that professor. He is on GR because he has placed introductions to this book and to others that he teaches in his classes. -

The wiki page for 'manifest destiny' has a picture of a painting by John Gast depicting an angelic figure (personification of America) purposefully drifting towards the west, her pristine white robes and blonde curls billowing in the breeze, a book nestled in the crook of her arm. Airborne, she awakens stretches of barren, craggy terrain to the magical touch of modernization. The landscapes she leaves behind are dotted by shipyards and railways and telegraph wires strung on poles but to her left the canvas shows a murky abyss - skies darkened by smoke from volcanic eruptions and fleeing native Americans gazing up at the floating angel in alarm.

Whenever I think of 'Blood Meridian' from now on, I hope my mind conjures up this same image not because both painting and novel provide perspectives, albeit contrary, on America's ambitious mid 19th century pursuit of extending its frontiers. But because Cormac McCarthy destroys this neat little piece of Imperialist propaganda so completely and irredeemably in his masterpiece, that all viewings of the image henceforth will merely serve to magnify the irony of this representation.

If John Gast's visualized panorama seeks to establish the legitimacy of the American Dream, vindicates the Godgiven right of determining the foundations of civilization, then McCarthy's vision of 'American Progress' brutally mocks the same and depicts the wild west as a lawless hunting ground submerged in a moral vaccuum. Here, there is no line of distinction between predator and prey. Heads are scalped, entrails ripped out, limbs dismembered, ears chopped off as trophies of war. Apaches, Mexicans, Caucasian men, women and children are skewered, bludgeoned, crucified and raped alike and so routinely and relentlessly that after a while the identities of victim and perpetrator blur into each other and only a dim awareness of any moral consideration remains at the periphery of our consciousness. The barrel of the gun and the sharpness of the blade speak in the universal language of might over right and all humanly attributes are silenced into submission.

The wrath of God lies sleeping. It was hid a million years before men were and only men have power to wake it. Hell aint half full. Hear me. Ye carry war of a madman's making onto a foreign land. Ye'll wake more than the dogs.

There are no protagonists here. Only creatures of instinct shambling along sun-scorched sand dunes, mesas and buttes, pueblos and haciendas, gravel reefs and dusty chaparrals, oblivious of the passage of time or the context of their grotesque exploits, unhesitatingly leaving a trail of mutilated corpses, carcasses and torched Indian villages in their wake. Jaded as one becomes from all the savagery, one does occasionally feel some measure of empathy for 'the kid' but then he vanishes often among the featureless, faceless individuals of Glanton's gang of scalp-hunters as they embark on a destination-less journey across the cruel, hostile terrain of the US-Mexican borderlands. In course of their blood-soaked, gory quest which McCarthy chronicles in exquisite turns of phrase, the identities of all the members of the band fuse together to symbolize something much more profound and terrible to comprehend all at once - the primeval human affinity for bloodshed which devours all distinctness of personality. Only the ageless Judge Holden towers over the other characters as the Devil's advocate with his lofty oratory on the primacy of war and his unabashed exhibitionism and seeming invincibility.

...war is the truest form of divination. It is the testing of one's will and the will of another within that larger will which because it binds them is therefore forced to select. War is the ultimate game because war is at last a forcing of the unity of existence. War is god.

In the last few pages when the Kid and the Judge parley in a sort of face off, I finally came to realize the real reason why the former is deprived of his centrality in the plot and relegated to the status of a mute presence in the background. As the eternal representative of the debilitating voice of morality which is always drowned out by fiercer cries for carnage, the Kid's internal sense of right and wrong, too, fails to resist the evil within. The Devil's cogent arguments, no matter how preposterous at times, negate all sporadic pricks of conscience.

If God meant to interfere in the degeneracy of mankind would he not have done so by now? Wolves cull themselves, man. What other creature could? And is the race of man not more predacious yet? The way of the world is to bloom and to flower and die but in the affairs of men there is no waning and the noon of his expression signals the onset of the night.

Needless to say, this is the grim rationale that underpins all the interminable slaughter. And such a solemn message leaves one with a lingering suspicion that if we peeled away the glossy veneer of democracy, modernity and the daily grind of mechanistic endeavours and reduced any society of humans to its bare bones, McCarthy's apocalyptic vision of an amoral world is the only thing that might remain - a perpetual heart of darkness. A conjecture as staggering in its enormity as it is bone-chilling. Perhaps, a conjecture with a modicum of truth to it. -

“War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner.”

Cormac McCarthy shockingly debunks the myths of the American western in this novel, a raw relentless immersion into the worst of humanity and the evil it perpetrates. It is not for the faint hearted as I discovered, a little way in I felt the strong urge to give up, but I just could not, partly because of the poetic prose that is so mesmerising and captivating. Based on the horrors of Texas and Mexico in the 1850s, we have the unnamed kid, the murdering Glanton gang scalping Native American Indians, but claiming centre stage is the vivid, larger than life, oft naked, absolutist dancing judge, bald, hairless, the child killer, deranged, the personification of evil, the destroyer. There are atmospheric descriptions of the landscapes in this unvarnished depiction of the human race's darkest side, a side I frankly did not really want to know about, but I cannot deny its existence throughout our history. Its presence here makes this a brutal, blood soaked, challenging read that is not for everyone, and which I can only recommend to those with the strongest of stomachs. Many thanks to the publisher. -

Quite possibly the most chilling and horrifying book ever written, 'Blood Meridian' is a unnerving glimpse of humanity at its worst during one of the most savage periods in American history. McCarthy pulls back the curtain to reveal the unforgivable evils and trespasses our species made all too often and all too easily in a new world, a novel that shows us the true price we paid in bodies and blood for the expansion of the 'Wild West'.

Unlike some of Cormac's other work, 'Blood Meridian' is not a particularly easy read for either style or subject matter. If your want to experience the work of this true literary master, I certainly wouldn't start with this book (Try 'The Road', or 'No Country For Old Men' to get your feet wet). Generally, I only advocate that people read well-written work that is fluid, pacey, and has total command of the language. But there are a handful of exceptions where I honestly believe that a good deal of effort is also required from the reader. 'Blood Meridian' is one such book, written on its own terms by an author who plays by his own rules. Sometimes you will have to work to get through the pages, but it is rewarding in ways you might not anticipate.

The brutality in this book is harrowing, and also true of the time. There have been countless analyses of it, so I won't get into the many themes, messages, and interpretations it offers. I will say that it does fall under the category of 'required reading' for everyone. However, it must be said that this book was not written for anyone's enjoyment. It wasn't written for entertainment. It was written to open your eyes to a hell on earth that humans willingly created, to open your ears to the beating of black hearts.

If this book doesn't shake your faith in the human race, then nothing will.

*This book was one of my '10 Books That Stuck With Me' piece. Check out my other selections:

http://www.jkentmessum.com/10-books-s... -

Tried twice, failed twice. Cormac has a good track record with me – Child of God is a 5 star classic, No Country for Old Men is a 4 star classic, and All the Pretty Horses is a solid 3 star.

I knew Blood Meridian was the Big One. The Masterpiece. The one that fuses together The Bible and Clint Eastwood. The Kid with No Name and the Book of Deuteronomy. Years ago I got to the Tree of Dead Babies and jacked it in, I got a lot further this time, but yes, I jacked it in again. I tried reading it as an extended metaphor – The Judge and his band of murdering renegades is like….Corona Virus! Of course! But it got a little tiresome : Judge/Corona comes to town, slaughters people, leaves. Repeat. Repeat without any end in sight.

GOOD AUTHORS CAN WRITE ONE BAD BOOK

Here’s a little list – I haven’t read these but I’m told they’re all dreadful

The Breast : Philip Roth

The Body Artist : Don Delillo

I Am Charlotte Simmons : Tom Wolfe

The Silmarillion : Tolkien

Dhalgren : Samuel Delaney

Jazz : Toni Morrison

The Name Of The World : Denis Johnson

But the point about Blood Meridian is that most people think it’s not bad, it’s great. I need to think about that.

CORMAC MCCARTHY’S LANGUAGE

On the level of plot, this book leaves something to be desired. But not all books have to have an interesting story. Some novels are essential for the brilliance of their language alone. Ain’t no story in Ulysses worth a bent farthing. And the whale is nowhere to be seen for most of Moby Dick. This type of book is on a whole other level, where vocabulary, clauses, gerunds, rhetoric works a magic to draw aside the clouds in our minds and present us with something grand we could not have suspected was there. Blood Meridian’s fans say that’s what this book does.

The horror of the American frontier, as McCarthy unflinchingly renders it, can prove rather wearying, not least for the book’s stubborn refusal to indulge in such niceties as comic relief or variations of setting and tone. What makes Blood Meridian endurable — what makes it so compelling once you adapt to its rhythms — is McCarthy’s prose. The man makes even the most repulsive images seem ineffably beautiful. He makes hell sound sublime.

And there are sentences here that will make you gasp in a good way .

They rode through regions of particoloured stone upthrust in ragged kerfs and shelves of traprock reared in faults and anticlines curved back upon themselves and broken off like stumps of great stone treeboles and stones the lightning had clove open, seeps exploding in steam in some old storm.

I love that, I have no problem with the and…and…and. But then you get other wanna-be-great sentences like this :

The ground where he’d lain was soaked with blood and with urine from the voided bladders of the animals and he went forth stained and stinking like some reeking issue of the incarnate dam of war herself.

It’s okay until “some reeking issue of the incarnate dam of war herself.” Then it’s just portentous empty gesturing. You could read that phrase in an early Marvel comic.

It seems I look at this stuff differently to some readers. One reviewer singled out this passage for great praise.

The flames sawed in the wind and the embers paled and deepened and paled and deepened like the bloodbeat of some living thing eviscerate upon the ground before them and they watched the fire which does contain within it something of men themselves inasmuch as they are less without it and are divided from their origins and are exiles. For each fire is all fires, and the first fire and the last ever to be.

But I get to the end of that and I think come on Cormac, stop trying so hard. Each fire is all fires. Horse is the horseness of all horse. Yeah yeah.

A TALE OF SOUND AND FURY SIGNIFYING NOTHING

A guy called Joseph Hirsch put his head above the parapet

I find the novel to be a pretentious, nearly-unreadable pastiche hybrid of every writer from Ernest Hemingway, to H.P. Lovecraft, to Norman Mailer.

….a blend of Hieronymus Bosch and Sam Peckinpah; of Salvador Dali, Shakespeare, and the Bible; of Faulkner and Fellini; of Gustave Dore, Louis L ‘Amour, Dante, and Goya; of cowboys and nothingness; of Texas and Vietnam.

Over the course of a novel of epic length, however, attempting to decipher the meaning of McCarthy’s words merely becomes a psychic endurance test. Along with Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, and Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, I read Blood Meridian cover to cover, not because I enjoyed it, but because I hated it, and felt that by finishing the book I was somehow defeating an unseen, unfathomably alien intelligence that had lured me into a masochistic test of wills, from which I could only emerge victorious after reading my way through the gauntlet of senseless words laid across the page.

SIMILES, SIMILES, I’M GIVING THEM AWAY TODAY, ONLY FIVE DOLLARS FOR A PACK OF TWELVE, ROLL UP, ROLL UP

In this novel, not in the others I have read, Cormac was gripped with a sporadic Tourette’s syndrome of similes. He just can’t help himself. For three or four pages at a time, out come the similes, they pepper the reader like… er…. Like…. Cormac, help me out here…

From pages 45-47

Like pencil lines

Like strands of the night

Like tentacles

Like an army asleep on the march

Like dogs

Like loom-shafts

Like sidewinder tracks

Like a ghost army

Like shades of figures erased upon a board

Like pilgrims exhausted

Like reflections in a lake

Like a great electric kite

Like slender astrolabes

Like a myriad of eyes

Like the palest stain

Like a land of some other order

Like some demon kingdom

So that began to wear me down too.

VIOLENCE

The endless chopping up of women in 2666 and American Psycho were too much for me, although I don’t have a problem with A Clockwork Orange and Titus Andronicus . I don’t claim to be Mr Consistent. But I hated the endless massacres in this one. And pretty much that's all there is. Maybe I just had my fill of violence. Blame the movies.

NO CONCLUSIONS FOR OLD MEN

Is this an existential cry of despair from the American past, followed by The Road, a cry of despair from the American future? Gotta say, that’s what it looked like to me.

Blood Meridian has now beat me to the ground and disembowelled me twice, there won’t be a third time. I quit. Stop kicking me, Cormac.

Acknowledgements : the nasty comments about BM are from an article called Why I don’t bow before Blood Meridian By Joseph Hirsch and the respectful comments are from James Dorson in his article Demystifying the Judge: Law and Mythical Violence in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. -

DANZA DI MORTE

The Evening Redness in the West.

In un mondo in cui regna la legge della natura, quella che premia il più forte, a scapito perfino del più intelligente, si aggirano uomini che agli occhi di un lettore della fine del XX secolo tutto sembrano meno che ‘naturali’: uccidono e sopraffanno, come avviene nel mondo naturale, ma loro addirittura incuranti se si tratti di animali o umani, incuranti di discernere tra umani adulti e umani bambini, tra maschi e femmine, tra giovani e vecchi.

Uomini o animali? Bestie? Barbari? Usano la stessa legge.

A differenza degli animali, tra quegli uomini esisterebbe uno straccio di legge, esisterebbero giudici e tribunali: ma chi ha il coraggio e la temerarietà di farla rispettare quando si tratta di fermare, giudicare, punire uomini che quella legge non rispettano e forse neppure conoscono, che sono più forti di chi quella legge dovrebbe proteggere e far eseguire?

Edward Sheriff Curtis: In Search of Lost Time.

Il west di McCarthy, di qua e di là dal confine col Messico, è un pianeta rosso sangue: per i tramonti infuocati, il colore della terra, e il sangue che viene sparso e versato.

The Kid, il protagonista giovane di questo romanzo apocalittico, ha quattordici anni quando se ne va da casa. Sale a cavallo, si porta dietro quello che indossa, e via. Andrà dentro e fuori di prigione, dentro e fuori bande e truppe, combatterà questo e quello, sia nativi che messicani che bianchi, collezionerà scalpi. Conoscerà il giudice Holden, il protagonista adulto, angelo e demonio, un personaggio degno dei cattivi di Shakespeare (Iago?), teorico della guerra perpetua, che predica come un testo sacro e razzola come un selvaggio. E, in qualche modo, si legheranno l’uno all’altro, per il resto della vita fino alla fine.

Perché, nonostante la strabordante violenza che The Kid eserciterà, subirà e alla quale assisterà, è destinato a crescere e diventare uomo. Nei decenni a cavallo del XIX secolo.

Il giudice Holden, il grande antagonista di The Kid, è stato definito il personaggio più terrificante (e inquietante) della letteratura americana. Completamente glabro, ecco come McCarthy lo descrive:

Riluceva come la luna, pallido, senza un solo pelo visibile in tutto il gran corpo, nemmeno in qualche piega della pelle o nelle grandi narici o sul petto o nelle orecchie, e neppure un’ombra sopra gli occhi o sulle palpebre.

Come si fa a non pensare a Moby Dick, che fu pubblicato proprio negli anni in cui è ambientato il meridiano di McCarthy (1851). O al Kurtz di Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now.

Le fondamenta degli Stati Uniti, il paese più potente del mondo intero, poggiano su una realtà come quella descritta da McCarthy: sono stati eretti e costruiti con e su quella violenza.

Ma io credo che McCarthy non si acconsenti di confinare quel suo mondo, recente

eppure così primordiale, alla sola eredità USA: è l’umano consesso dell’intero globo che si deve confrontare e misurare con quella violenza inesauribile, ingiustificata, straripante. È il mondo in sé a essere cruento e raccapricciante. Caotico. Senza pietà. Regno dell’ira. Pregno di sinistra bellezza.

Il mondo in cui viviamo è un errore cosmico? Esiste un qualche tipo di sentimento?

Naturalmente i luoghi dove l’azione si svolge, l’ambiente e lo scenario riflettono e amplificano la violenza biblica dell’uomo cacciatore, che sembra mosso solo da un istinto omicida. In queste pagine si incontrano massacri così spaventosi, violenza, mutilazioni, che viene da paragonarlo al rapporto delle Nazioni Unite sugli orrori commessi in Kosovo.

McCarthy non giudica, non spiega, non prende le distanze: descrive, racconta. All’apparenza, impassibile.

Questo è stato il mio primo incontro con la letteratura firmata da Cormac McCarthy. E credo che non potevo iniziare meglio: si tratta probabilmente del suo apice artistico. Anche se probabilmente meno letto di altri suoi romanzi quali La strada o Non è un paese per vecchi, lo reputo decisamente superiore. La furia omicida che McCarthy racconta e mette in scena ricorda da vicino quella della mitica balena bianca, Moby Dick. O quella degli Achei all’assedio di Ilio.

Qui McCarthy usa ancora lingua ostica e barocca: il che forse spiega il minor successo di questo eccellente romanzo rispetto a quelli più recenti, baciati da buone trasposizioni cinematografiche, nei quali la scrittura s’è fatta più scarna e agevole.

Giacomo Borlone de Buschis: Trionfo e danza della morte (1484-1485). Oratorio dei disciplini di Clusone, in val Seriana, provincia di Bergamo. -

Some people say that this is Cormac McCarthy's best work. I don't agree with that, even though I have to say that this is nothing less than an astonishing work of art.

This novel deals with the unrelenting brutality of the Glanton gang, an actual historical group of men who scalped and savaged Indians and Mexicans across the American Southwest in the mid 1800s. From the first page you feel like you've entered someone's nightmare. There's no place to hide here from the viciousness, the barrenness, the moral vacuousness. The violence is over the top. The book is saturated in blood, in murder, one after the next. And it sports a villain that chills you to the bone - The Judge - who, more often than not, is naked, and doing something insanely grotesque, despite his intelligence and ability to wax eloquent.

It feels like one long massacre, with no rhyme or reason. At first you think that these men killed out of some kind of political stance on the American-Indian war. Or perhaps they are economically motivated, through looting. But their impetus shows itself to be more arbitrary. It's not the Americans vs. the Indians. One side isn't much better than another. It's the Glanton gang against whoever, whenever. They are a dangerous, twisted bunch with no loyalty or compass.

And the reader is also without a compass, in a way. The reader is adrift, along with this band of criminals. The plot is formless. There isn't a protagonist to follow, unless you count "The Kid" who isn't any better or different from the rest of them. There isn't a story, per se, or a destination, or a problem to resolve. The reader serves as witness to this gloom of a world, this river of gore.

McCarthy’s world echoes of Old Testament life, in which each person serves as a cog in a brutal story. Only this novel is bereft of a god, or anything to believe in.

Some say this epic story is an anti-western. A horror. A scathing indictment of imperialism, of the American "manifest destiny". I'd agree on all those counts, and add that the writing of this book is unlike anything I've read before - completely extraordinary, genius, devastating.

But I don't know that it's the best book McCarthy has written. Although I can stand back and say, wow, what a brilliantly written book - and I'm so glad I read it - did I enjoy reading it? Not nearly as much as No Country for Old Men, which was so tightly plotted I got whiplash by how fast I turned the pages. Not nearly as invested and heartbroken as I was reading The Road. Not as beguiled as I was by All the Pretty Horses.

I witnessed the nightmare. I lived to tell the tale. And now, like the riders, after seeing the unseeable, I'll move on. -

Ματωμένος Μεσημβρινός ένας συγκλονιστικά λογοτεχνικός εφιάλτης.

Ένα χρονικό αφιερωμένο στην απόλυτη αποκτήνωση του ανθρώπου.

Μια φρικιαστική ελεγεία για την αληθινή κόλαση σε κάποιον άλλον «πλανήτη» με είδωλα και σφραγίδες απο καμμένη σάρκα και αίμα.

Ίσως, να περιγράφεται ο προορισμός των αμαρτωλών και σκοτεινών ψυχών.

Ίσως ο τόπος που θα βρεθούμε μετά το θάνατο μας όλοι. Εκεί που η ψυχή πετιέται σε ένα ιριδίζον ονειρικό σκηνικό αποκάλυψης, σε ένα ερημικό, πρωτόγονο πανόραμα που η ξηρασία ποτίζεται μόνο με αίμα για να παραμείνει καταραμένη.

Εκεί αντανακλάται η κατάσταση της ανθρώπινης ψυχής και αυτή είναι η παγκόσμια ανθρώπινη ιστορία.

Στον μεσημβρινό του αίματος τα πάντα καθορίζονται απο τις ενέργειες των χαρακτήρων-ανθρώπων.

Δεν υπάρχει πλοκή όπως ακριβώς και στην καθημερινή μας ζωή.

Δεν απέχει απο την εκπληκτική ομορφιά ή τη βαρβαρότητα που προκαλείται απο έναν ασυνείδητο πολιτισμό και επηρεάζεται απο ένα τυχαίο χάος το οποίο έχει αταβιστικά πάντα ενα πρότυπο.

Πόλεμος. Βία. Θάνατος. Εκφυλισμός.

Απο τα αρχέγονα τοπία μέχρι τα μεσαιωνικά βασανιστήρια που περιγράφονται σε αυτό το βιβλίο είναι αναγνωρίσιμη μια μεγαλύτερη δύναμη.

Μια φυσική έλξη στην ελεύθερη θέληση και στα μονοπάτια του χάους που μας κάνει να αμφισβητούμε οτιδήποτε διαμορφώνει τις ασήμαντες ζωές μας και τις εποχές στις οποίες ζούμε.

Μια παραβολή είναι όλο το βιβλίο, μια αληθινή αλληγορία για απάνθρωπες στιγμές σε απάνθρωπες στιγμές.

Σε αυτό το έργο βασίζεται η ανθρωπότητα και θα μείνει για πάντα χαραγμένο στην μνήμη μου.

Είναι ένα ηλεκτροφόρο καλώδιο συνείδησης.

Δεν υπάρχει φίλτρο στην φρικωδία ή λογοκρισία.

Δεν υπάρχουν ήρωες.

Απλά μνημειακή ομορφιά και ανυπέρβλητη φρίκη σε κάθε σελίδα.

Ο συγγραφέας εκπέμπει ένα φως απο την ψυχή του, παρόλο που η γραφή του ξεκινάει στο σκοτάδι, φτάνει στο αιματοβαμμένο μεσημβρινό τοπίο της κοκκινωπής νύχτας και τελειώνει στο σκοτάδι.

Η δράση σε αυτό το ψυχοπαθητικό μυθιστόρημα ερημιάς εκτυλίσσεται στις περιοχές των συνόρων μεταξύ ΗΠΑ και Μεξικού.

Χρονικά είμαστε στην περιοδο (1841-1890).

Τοπικά βρισκόμαστε σε ένα αχανές τοπίο κόλασης στο οποίο διαπράττονται όλες οι βασανιστικές φρικαλεότητες ωμής βίας και θανάτου.

Σε αυτήν την κόλαση άρχει ο παντοδύναμος θεός Πόλεμος.

Μια βάρβαρη συμμορία μισθοφόρων και άγριων ιθαγενών αλωνίζει την κόλαση.

Είναι κυνηγοί κεφαλών. Σκοτώνουν ινδιάνους και εμπορεύονται τα κρανία τους.

Απο καποιο σημείο και μετά οι φόνοι δεν έχουν όριο.

Η λεγεώνα του αίματος χαράζει ένα μονοπάτι στην άγρια Δύση της Αμερικής και ξεκινάει την επική αναζήτηση θυμάτων,

κάθε φυλής-θρησκείας-χρώματος-φύλου - ηλικίας-ενοχής-αθωότητας.

Τα κομμένα κεφάλια συνεπάγονται χρήμα, ποτό, γυναίκες και απολαύσεις.

Η κτηνωδία σε όλο της το μεγαλείο κατοικεί στο μυαλό αυτών των τρομοκρατών, των ιπποτών της Αποκάλυψης που σκορπούν ακραία βιαιότητα, θάνατο και καταστροφή σε κάθε γωνιά της ερήμου.

Εκφυλισμένοι δολοφόνοι που ταξιδεύουν εξαθλιωμένοι και παρανοϊκοί αναζητώντας θύματα.

Ας πούμε πως σε αυτή την απάνθρωπη εσχατιά δεν υπάρχει τίποτα πιο καθημερινό απο εικόνες δέντρων στα κλαδιά των οποίων κρέμονται νεκρά κατακρεουργημένα μωρά.

Απο ήρωες που φορούν στο λαιμό τους περιδέραια στολισμένα με κομμένα αυτιά θυμάτων και κρατούν στις τσέπες τους για γούρι αποξηραμένες ανθρώπινες καρδιές.

Εικόνες όπου τα στόματα των νεκρών είναι φραγμένα με τα γεννητικά τους όργανα.

Εικόνες που θρυμματίζουν την ψυχή του αναγνώστη.

Ανάμεσα σε αυτά τα όντα που είναι ζώα με μορφές ανδρών ξεχωρίζουν δυο φιγούρες διαφορετικές.

Ένα μικρό αγόρι απο το Τενεσί που το σκάει απο το άθλιο σπίτι του και ενσωματώνεται ως μαχητής επιβίωσης σε αυτή τη συμμορία.

Ένα παιδί που δεν μεγάλωσε ποτέ.

Δεν αγάπησε και δεν αγαπήθηκε. Δεν ωρίμασε ποτέ, ενηλικιώθηκε μέσα στο αίμα και συναισθάνθηκε μόνο εφιάλτες.

Η άλλη φιγούρα που πρωταγωνιστεί και υπάρχει παντού είναι ο δικαστής Χόλντεν.

Ένα αποπνικτικά αξέχαστο πλάσμα αλλοτινό. Εμφανίζεται σχεδόν βιβλικά στην έρημο όταν η συμμορία βρίσκεται σε κατάσταση μεγάλης ανάγκης και προσφέρει βοήθεια.

Όλα τα μέλη της ομάδας ισχυρίζονται πως τον γνωρίζουν απο κάποια ξεχασμένη εποχή.

Ο δικαστής έχει μια φιλοσοφική άποψη της ακραίας βίας του. Είναι τερατώ��ης, σατανικός, πολύγλωσσος, μορφωμένος, αινιγματικός και σίγουρα πολύ μεγαλύτερος ηλικιακά απο την ίδια τη ζωή.

Κεντρικός ήρωας της ιστορίας μας ως είδωλο ενός στοιχείου της φύσης που οι περισσότεροι άνθρωποι προτιμούν να μην σκέφτονται την ύπαρξη του....

Σας θυμίζει κάποιον;

Έχω καταβροχθίσει πολλά βιβλία διαφόρων ειδών, αυτή η βάρβαρη ποιητική οδύσσεια του Μακ Κάρθυ με συνεπήρε εξοντωτικά.

Αυτός ο μεσημβρινός τίτλος που ίσως να είναι ο 98ος παράλληλος, η γραμμή μεταξύ πολιτισμού και κόλασης συνόρων, είναι μια άγρια πτώση στα ανθρώπινα βάθη γεμάτη δύναμη και μεγαλοπρέπεια.

Ένα αριστούργημα που καταγράφει τις πεποιθήσεις για τις ανθρώπινες ιδιότητες που καθορίζουν τις έννοιες της τραγωδίας, της κάθαρσης και της επικράτ��σης του κακού σταθερά, σε κάθε εποχή και μέρος της ιστορίας της γης.

Επικράτηση του κακού ουσιαστική και καθολική δίπλα μας, μέσα μας, όχι εκτοπισμένη στις διαφορες θρησκευτικές κρίσεις.

Όσο μακριά κι αν φαίνονται τα σύνορα του Μεξικού το 1850 ο συγγραφέας έχει να πει κάτι πολύ σημαντικό.

Διαβάστε το.

Και θυμηθείτε τον δικαστή.

Χορεύει πάντα και δεν πεθαίνει ποτέ!!

Καλή ανάγνωση.

Πολλούς ασπασμούς. -

Sordid Origins

The myth of the American Southwest has it that it was the last uncivilised part of the North American continent. This was the frontier of hearty cowboys, stalwart settlers, and other pioneers who, despite the occasional gunfight at the OK Corral, gradually brought law and order, white Protestantism, and eventual prosperity to this benighted land. That huge area between the grassy plains of East Texas and Upper California was not just a place of adventure, it was also the scene of the American mission, as much a symbol of the Republic as the legends of Washington crossing the Delaware and Daniel Boone’s travail with a bear.

According to Blood Meridian this is all nonsense. The region had been Spanish for 300 years before the Yanquis decided it should be theirs. Much older native cultures - Apache, Hopi, Navajo, Pueblo, and Zuni - persisted through colonisation. Into this unstable social equilibrium, America brought not civilisation but dystopia. The folk who felt themselves moved to carry the Stars and Stripes into this vulnerable territory were not noble pioneers but drifters, grifters, chancers, and no-accounts. What they brought was not improved institutions of government but brutal chaos. The gene pool of the Southwest was more or less permanently polluted by the mentally defective and the morally unfit.

McCarthy’s descriptions of the place itself are unparalleled in the beauty of their language. They evoke precisely the kind of romantic sentiment that dominates popular perceptions:“Tethered to the polestar they rode the Dipper round while Orion rose in the southwest like a great electric kite. The sand lay blue in the moonlight and the iron tires of the wagons rolled among the shapes of the riders in gleaming hoops that veered and wheeled woundedly and vaguely navigational like slender astrolabes and the polished shoes of the horses kept hasping up like a myriad of eyes winking across the desert floor... All night sheetlightning quaked sourceless to the west beyond the midnight thunder-heads, making a bluish day of the distant desert, the mountains on the sudden skyline stark and black and livid like a land of some other order out there whose true geology was not stone but fear. The thunder moved up from the southwest and lightning lit the desert all about them, blue and barren, great clanging reaches ordered out of the absolute night like some demon kingdom summoned up or changeling land that come the day would leave them neither trace nor smoke nor ruin more than any troubling dream.”

But these dramatic scenes are peppered with grotesque narratives of human senselessness and cruelty:“With darkness one soul rose wondrously from among the new slain dead and stole away in the moonlight. The ground where he'd lain was soaked with blood and with urine from the voided bladders of the animals and he went forth stained and stinking like some reeking issue of the incarnate dam of war herself... The murdered lay in a great pool of their communal blood. It had set up into a sort of pudding crossed everywhere with the tracks of wolves or dogs and along the edges it had dried and cracked into a burgundy ceramic. Blood lay in dark tongues on the floor and blood grouted the flagstones and ran in the vestibule where the stones were cupped from the feet of the faithful and their fathers before them and it had threaded its way down the steps and dripped from the stones among the dark red tracks of the scavengers.”

The book was published 35 years ago but it is a timely reminder of the psychological projection that has always been a part of the culture of white North America. The receptivity of Americans to Trump’s characterisation of immigrants from the South as thieves rapists, and murderers is nothing new. It is America which sent just these as its vanguard of empire. This is a permanent embarrassment and a source of much of present day conflict. As the protagonist is instructed by one of his fellow desperadoes:“But where does a man come by his notions. What world's he seen that he liked better?... No. It's a mystery. A man's at odds to know his mind cause his mind is aught he has to know it with. He can know his heart, but he dont want to.”

It is obvious to the rest of the world that America still does not want to know its own heart, nor its own sordid origins. -

In the old west, a young man falls in with a bad crowd, scalphunters, and the worst of them all, the judge.

It's not often when I can't figure out how to summarize a book. Not only does Blood Meridian fall into this category, I'm also struggling with trying to formulate my thoughts about it. I'm sure it's one of those big important books that has themes and things of that nature. It seems apocalyptic at times, with the judge showing the kid the horrors of the world, kind of like the devil and Jesus in the desert.

Cormac McCarthy's prose is simple but powerful. It also feels really smooth, like he barely had to work at it at all to get it on the page. It has an almost Biblical feel to it. Once the kid hooks up with the judge and the Glantons, things get worse and worse, like getting kicked in the crotch by progressively more spiky shoes.

There were a lot of times during my read of Blood Meridian where I had to stop and digest what I just read. It had a dreamlike, or nightmarish, quality a lot of the time. The judge is by far the most memorable character in the piece.

The book really doesn't have much of a plot, just scene after scene of brutal violence. I read a lot of detective stuff but this was one of the most violent books I've ever read. I could only read it for 30-45 minutes at a time before I had to stop and digest.

Lastly, what's with the lack of quotation marks? Was McCarthy sexually assaulted by quotation marks while he was a boy scout?

Four stars, but not for the squeamish. If you have any amount of squeam in you, you'll be squeaming all over the place in no time. -

*Updated, now with an additional McCarthyized section of the Bible, moved up from the comment section.*

Here's what I'm thinkin.

THE CORMAC MCCARTHY PROJECT

Ever since reading Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, I've been considering the possibilities of revisiting the classics and, um, reinterpreting them. Butchering? Yes, you're probably right. Butchering them. That's the right word.

Anyway, since Cormac McCarthy has the most distinctive and powerful voice of any modern writer (that I've read recently)(in my opinion), I pose the question: what if Cormac McCarthy were to revisit the classics of the English canon? What if McCarthy had been the author of The Great Gatsby? How would it have ended up? I think this is an important enough question to begin a new writing project, or, at the least, write a Goodreads review pretending I'm going to.

First, we have to establish these new versions of the classics will be stylized after McCarthy's Western Novels, starting with Blood Meridian and ending with Cities of the Plain. Characteristics include:

1) No punctuation other than periods and question marks.

2) No indication of who is talking during dialogue, although you can always tell.

3) Poetic descriptions of barren landscapes which often reflect the callous indifference of nature to the plights of humanity.

4) Untranslated Spanish dialogue.

5) No hint of the characters' internal dialogue; all characters are revealed only through action and conversation.

6) Gratuitous and unexpected acts of horrendous violence.

7) During casual conversation, characters frequently say incredibly profound shit.

Although there's more to his style than this, we can take this as the most bare-essential aspects of what is necessary to properly "translate" a novel into its McCarthy version.

As an example, let's take a certain scene from Pride and Prejudice. How about the one where Lady Catherine is quizzing Elisabeth about whether D'arcy has indeed proposed to her? They're alone, walking in the garden (although in the McCarthy version, they would be walking upon a windswept moor). Here we go:

+++++++

Dust clung to their boots and the tall grass shuddered on the frigid wind. A raven perched upon the fallen branch of an elm and watched them with one jet eye. Lady Catherines hands grasped nervously at nothing as she looked across the moor.

Young women of unfortunate birth shouldnt attempt to reach beyond their station.

What?

Don't pretend you don't know of what I speak.

Eliza spat and turned away. She walked into the doorway of a church. Inside dozens of bodies lay heaped upon the floor. Blood hard and dried like clay caked upon the stone of the floor. Flies traversed upon the eyelids of a child that stared blankly at Eliza who turned away.

Los Muchachos estan muerto.

Muerto?

Muerto.

Si.

Eliza brushed her hair back. All of the constrictions you place upon mans actions are nothing to the ineffable stretch of the world which knows that all is war. No system of morality is anything but pretense which the least of gods vile beasts can shatter simply through the act of killing for its survival. Morality holds no water when it stands eye to eye with stark reality.

Lady Catherine spat and wiped her mouth on her sleeve.

Its damn cold.

Wait which of us said that?

I did.

Oh. Alright.

I wont promise I would never accept a proposal if I dont think its ever to be given. Nor can I swear as to what I would do in a situation that Ive never known myself to be in.

Well arent you a contrary little whore. Lady Catherine spat. Ill not forget how youve treated me this day. Her finger moved closer to the knife that hung at her hip.

++++++

And here's one of the Bible's more memorable passages, McCarthyized:

19:1 From out the dark sky over all Gods reckoning the two drifted like fallenleaves downward as Lot tipped back the widebrimmed hat, rubbing his thumb over stubble and spat on the grounddirt. Raising heavy to his feet and stretching he ambled forward dust raising an etherial plume in the nightair like ghosts of sinners dwelling on the threshold of the dark. the untamed past hovered there in the darkness by Sodom.

19:2 Come in ifn you want.

We don't mind sleepin outside.

No really I got plenty room. Cmon in.

The angels came in bare feet on the packed dirt covered with indescribable years of footprints crisscrossed into an impossible to fathom reckoning of feet stretching back through indescribable years. So many feet and such a dirty floor.

19:3 He cooked bread. They warshed up and ate.

19:4 Out the window shadows encroached from the jet locustridden expanse of Sodom. Figures in stillness, nooses dangling from withered hands and that dust rising like the dead pounding from the other side of eternity trying to return trying to be unforsaken from the temporal purgatory the men dwelt in. Who them men we saw with them white robes.

19:5 Gone home, Jenkins, he said.

Not til we know who them fugitives is you harborin. They aint niggers is they.

Didn't you see they white robes. They aint no niggers.

Lot walked out the house into that humidity the wind like the word of God drifting with threats of retribution and reckoning. Tell you what, men, you better get back on home and mind ya damn business. This aint no affair of yourn.

The Willis boy had a strapon fixed to his forehead pointing up accusingly at the heavens an erection of defiance. He wore that collar that said Slave as always. He was danglin handcuffs from his hand like like a hypnotist without a pocketwatch. We just wanna see um. We just wanna meet um. Maybe have a little fun with um.

19:7 Lot spat a wad of nasal discharge loudly upon the earth and glanced back at the house. Tell you what boys. I invited them men into my house and I wont have them mistreated but I got them two good fer nothin daughters. You leave my visitors alone Ill bring them on out.

19:8 Willis nodded, that plastic tusk swaying in the nightair. What fer.

Whatever yall find fittin. It aint fer me to say. Just leave my visitors alone.

Okay, apparently it's not easy to write in Cormac McCarthy's style without sucking. I suppose the only way THE CORMAC MCCARTHY PROJECT can be effectively carried out is if McCarthy himself were to actually write these translations. So, if anyone runs into Cormac, let him know about this project, and how important it is for him to get to work right away. After all, there are lots of classics. I believe he lives in New Mexico. So, if you're wandering through a dark, dank cave and hear the sounds of typewriter keys pounding away, you've probably found his lair. Approach slowly, and don't make eye contact.

I suppose, while I'm at it, I could say something about Blood Meridian. FUCKING AMAZING! I hate giving five star ratings, probably because I'm so curmudgeonly. But, for the third time, McCarthy is making me give him one. I just can't find anything to fault here, and the story is different from any I've ever read before. The writing is amazing, the characters are good (although the Judge fits a certain fiction stereotype, he's a very memorable version of it), and I was startled by the horror of it all . . . until I became numb to it. Which was the intention, or I think it was at any rate.

This is the horrifying story of a group who are being paid to hunt down injuns and scalp them. Over time, the bloodlust of the group grows and they begin scalping those they're intended to be saving, and basically everyone they come across. When it comes time to be paid for the scalps, the scalps all look the same anyway. Sothey make tons of money from the indiscriminant slaughter of soldiers, villagers, travelers and everyone else. And, from there, things get uglier.

This is all based on historical events, or so I've heard. I haven't researched it enough to know how closely. But, this is a very dark vision of the "wild west," and the blood that was spilled while the land was still wild. If you have the stomach for it, this is an amazing book. -

*3rd read - this time I tackled the audio and it was mega immersive.*

*2nd read - even better this time around. A masterpiece of violent and poetic art.*

Here is my review for Blood Meridian on Grimdark Magazine. My first Cormac McCarthy review for the site!:

Grimdark Magazine

Blood Meridian. This novel by Cormac McCarthy is a book that disturbed me to my core and made me dwell on the realities and philosophies within it. I have struggled to type what I actually think about it and have thus far failed to put into words my feelings around it. But I cannot stop thinking about it. I’ll leave this quote here:

“The truth about the world, he said, is that anything is possible. Had you not seen it all from birth and thereby bled it of its strangeness it would appear to you for what it is, a hat trick in a medicine show, a fevered dream, a trance bepopulate with chimeras having neither analogue nor precedent, an itinerant carnival, a migratory tentshow whose ultimate destination after many a pitch in many a mudded field is unspeakable and calamitous beyond reckoning."

Cormac McCarthy is considered to be America’s best living author. He has written works that have been turned into films - The Road; No Country for Old Men; All the Pretty Horses and Child of God. I have had swarms of recommendations to read something by McCarthy, due to his god-like prose and his dark story-telling. After this single read, I feel it is my job to also recommend and subject everyone I meet to Blood Meridian.

“It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way.”

Blood Meridian or, subtitled as; The Evening Redness in the West (appropriate subtitle by the way), begins in the 1850s Texas-Mexico border. It follows a 14-year old boy we only know as ‘the Kid’ who flees his home in Tennessee and heads to Texas. His journey takes twists and turns leading him to become a scalphunter - joining the infamous Glanton Gang and being paid for each and every Native American scalp in a world that is just as cruel as that sentence sounds.

“The wrath of God lies sleeping. It was hid a million years before men were and only men have the power to wake it. Hell aint half full. Hear me. Ye carry war of a madman’s making onto a foreign land. Ye’ll wake more than the dogs.”

I have since found out that the Glanton Gang that McCarthy wrote about is actually a historical gang that actually went around killing and scalping Native American tribes in the 1850s and actually got paid to do so. Cormac McCarthy based this novel from the book ‘My Confession: Recollections of a Rogue’ written by Samuel Chamberlain - a man who rode with the Glanton Gang - which is considered to be the best account we have today of a soldier’s life in the Mexican War. Glanton’s Gang are established and acutely cold-hearted and professional as can be, their leader John Glanton a fearsome, gritty soldier. McCarthy’s writing of Glanton is hideously and brutally factual, showing the horror of such a leader and the stone-cold composition this person had to commit the savage acts they did.

“Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent.”

This book centres around the character the kid and his journey within the Glanton Gang, but there is one character who this book is about. The Judge Holden. The Judge is a terrifying character, devoid of emotion and any humanistic traits. He is a giant, hairless murderer and psychopath. The Judge had monologues that displayed his philosophical thinking and his inhumanity that were in some parts exhilarant and in more parts just ridiculously menacing. He is spine-chilling and every line within this book about him will disturb you. Especially the last line, which led me to hold my head and let out a sigh for what felt like forever. As you read this book you will decide who The Judge really is. Some say he is the devil, others that he is everything evil within us, some that he is just a man with no compassion in the Wild West.

“If God meant to interfere in the degeneracy of mankind would he not have done so by now? Wolves cull themselves, man. What other creatures could? And is the race of man not more predacious yet?”

Within Blood Meridian I really discovered what the word ‘grim’ meant. There is no respite or interlude of the mass-chaos that the gang ensue. As a group of men who’s sole purpose is to scalp men, women and children, you know it isn’t going to be a light-hearted book. But McCarthy writes with a prose that is biblical, and the horrifying acts that are committed are written in the most un-gratuitous way which makes it all the more vicious. This book should have a massive ‘IF YOU ARE SQUEAMISH, AVOID’ sticker on. The brutality is moderately standard for Grimdark novels until around the 160page mark where the author really turns up that gore. Really.

“The jagged mountains were pure blue in the dawn and everywhere birds twittered and the sun when it rose caught the moon in the west so that they lay opposed to each other across the earth, the sun whitehot and the moon a pale replica, as if they were the ends of a common bore beyond whose terminals burned worlds past all reckoning.”

Cormac McCarthy’s prose must be praised here, as his accomplishment to write a book that is so poetic and metaphorical and make it seem so natural is quite incredible. I have only read this book once and I can see myself reading it many more times as I feel I have only just scratched the surface of his true thoughts and meanings within the subtleties of the language he uses. He avoids punctuation, especially speech, he writes long-winded sentences and repeats and a lot, he breaks all of the ‘literary rules’ and really makes it work.

“They were watching, out there past men's knowing, where stars are drowning and whales ferry their vast souls through the black and seamless sea.”

I usually love to read a story that is all about being behind the main character and his friends. Wanting the character to prevail or succeed. There is none of that within Blood Meridian, until the last 60 or so pages. Blood Meridian doesn’t need anything extra. It is an achievement of writing and a book that can only be described as genius. The ambiguity of the ending left me wanted to scream and sleep at the same time and just added to the horror that I had read for the previous 350 pages.

“Only that man who has offered up himself entire to the blood of war, who has been to the floor of the pit and seen the horror in the round and learned at last that it speaks to his inmost heart, only that man can dance.”

5/5 - It’s hard to put into words how this book has made me feel. I finished it last week and still cannot comprehend it, but also cannot stop reflecting back on it. Cormac McCarthy’s writing is sublime and this book is well and truly Grimdark. Not for the faint-hearted. Please let me know if you read it or have read it, I’d love to talk about your thoughts! -

This is the nature of war, whose stake is at once the game and the authority and the justification. Seen so, war is the truest form of divination. It is the testing of one’s will and the will of another within that larger will which because it binds them is therefore forced to select. War is the ultimate game because war is at last a forcing of the unity of existence. War is god.

Set in the old West primarily in the 1850s, just after the Mexican-American War, Blood Meridian is objectively a great work of literary fiction. It is full of all the things one wants from a work of important literature. Great writing. A unique and memorable character in Judge Holden. Symbolism. It is so atmospheric that the desert in effectively the third most important character. Much of its meaning is open to interpretation.

So what’s not to love about Blood Meridian? Well, I’m not sure I’ve ever read a book so full of violence. I mean Quentin Tarantino levels of violence. Is there a point to it? I suppose. It shows the progression as the gang descends from attacking hostile Indians, to peaceful Indians, to townspeople, and finally to soldiers. In one scene, the Judge buys two puppies just to throw them into the river and watch them drown. So yeah, I’d argue it’s gratuitously violent. And, a large portion of the book—like the middle two-thirds—is largely just the characters traveling around from town to town, committing one violent act after another. The plot, such as it is, only picks up in the book’s final pages.

Still, I found myself thinking about Blood Meridian quite a bit in the days after I finished it, and off and on ever since. In some ways it reminded me of

The Red Badge of Courage and

Heart of Darkness. But what did it all mean? If you believe the Judge killed the Kid at the end (and not everyone does), then why did he? Because he was the last witness to the exploits of the Glanton Gang? Because of the differences in their moral codes? And was the Judge a man at all, or some type of Devil? His presentation throughout the book—and the fact that he was easily the most interesting character—left me thinking about the Devil in

Paradise Lost. And it seems more than 30 years later, no one knows how to interpret the epilogue.

Blood Meridian is truly a great book, but not exactly a good book. It’s not an easy read, nor particularly entertaining. But if you enjoy challenging literary fiction, and you’re ok with gratuitous violence, Blood Meridian is a modern classic. -

No hay ninguna duda de que McCarthy es uno de los grandes y esta es una gran novela que, no obstante, me ha gustado algo menos que Todos los hermosos caballos o En la frontera, menos sangrientas y simbolistas.

Meridiano de Sangre está contada con un gran realismo aunque no sea una novela realista. Es una novela épica sobre la maldad absoluta y llena de simbolismos que, reconozco, no siempre he sabido descifrar convenientemente. Es un relato del infierno en un entorno infernal y con personajes infernales (el juez Holden es magistral), que contrasta tremendamente con la bella prosa, barroca, poética la mayor parte, y difícil en muchas otras, con la que está relatado. Un testimonio fabuloso de hasta dónde puede llegar la maldad del ser humano, por el fondo, y la excelencia de su arte, por la forma.