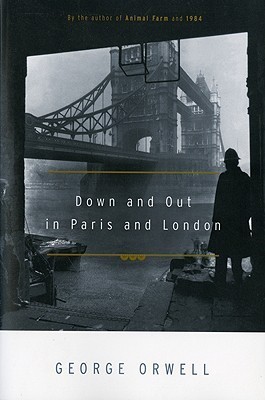

| Title | : | Down and Out in Paris and London |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 015626224X |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780156262248 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 213 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1933 |

Down and Out in Paris and London Reviews

-

Do not read this book if you are unemployed.

Do not read this book if you are homeless.

Do not read this book if you are worried about the tanking economy.

Do not read this book if you have no retirement savings.

Do not read this book if you don't like eating stale bread and margarine.

Do not read this book if you like eating in restaurants.

Do not read this book if you are sensitive to foul odors.

Do not read this book if you are one of those people who carries a hand-sanitizer at all times.

Do not read this book if you are an artist, writer, musician or other creative occupation which certainly guarantees brushes with poverty.

If you do read this book (which I highly recommend) make sure you have some bubble bath on hand as you will need a nice long well-perfumed soak afterwards. -

As anyone who has read 1984 can attest, Orwell is--among other things--a master of disgust, a writer who can describe a squalid apartment building, an aging painted whore or a drunken old man with just the right details to make the reader's nose twitch with displeasure, his stomach rise into the throat with revulsion. What makes this book so good is that--although he may continually evoke this reaction in his account of the working and the wandering poor--Orwell never demeans or dismisses the human beings who live in this repulsive environment. The people he describes may be disgusting, but they are often resourceful too, and Orwell makes it clear that it is the economic system itself--not the character flaws of particular individuals caught up in the system--which is to blame for so much squalor and suffering.

I would recommend this book to anyone who wishes to read a vivid description of the conditions of those who live beneath the underbelly of society and the stratagems they use to survive, whether they be recently impoverished men endeavoring to maintain respectability, Paris dishwashers sweating through their underground existence, or British tramps enduring the daily bone-wearying trek for a cheap place to lay their heads. -

“It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out. You have talked so often of going to the dogs - and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it. It takes off a lot of anxiety.”

In 1927 Eric Arthur Blair A.K.A. George Orwell gives up his job as a policeman in Burma and moves back to his lodgings on Portobello Road in London with the intention of being a writer. Like with many artists, writers, and those that wished to be one or the other, the siren song of Paris beckoned Orwell. In 1928 he moves to The City of Light.

”It was lamplight--that strange purplish gleam of the Paris lamps--and beyond the river the Eiffel Tower flashed from top to bottom with zigzag skysigns, like enormous snakes of fire.”

His lodgings are robbed byan Italian mana trollop he has brought back to his room for what can be presumed for a carnal dalliance, but one must have a proper story for the parents especially when one is soliciting funds. This is really the beginning of a rather abrupt slide into poverty. Little did he know this change of circumstances was going to provide him with the material he needed to get published.

A gagger--beggar or street performer of any kind.

I do hope that everyone has had an opportunity to experience some poverty. When I was in college I had several moments where my gas tank was on E, that amber dot nearly burned a hole in my retina, and well food, skipping a few meals builds character. The one thing that I learned about my brief bouts of impecuniousness was that I didn’t like it. The anxiety of potentially revealing the precarious nature of my affairs was much more excruciating than the discomfort of hunger or even the tension inspired by the keenly tuned ear listening intently for the first cough of an engine starved for gas.

The mind does sharpen when deprived of nutrients.

A moocher--one who begs outright, without pretense of doing a trade.

A slice of Orwell’s Paris.

Orwell does become truly down and out barely scraping together enough money to maintain lodging. Everything pawnable or salable is already in the shops and now he must find a job. He tramps for miles all over the city following rumors of employment. He finally lands a position at a hotel restaurant washing dishes. It isn’t particularly difficult work, but the hours are unbelievably long. Since he is on the lowest rung of the very tall totem pole he is roundly cursed by everyone.

”Do you see that? That is the type of plongeur they send us nowadays. Where do you come from, idiot? From Charenton I suppose?” (There is a large lunatic asylum at Charenton.)

“From England,” I said.

“I might have known it. Well, mon cher monsieur, L’Anglais, may I inform you that you are the son of a whore?”

I got this kind of reception every time I went to the kitchen, for I always made some mistake; I was expected to know the work, and was cursed accordingly. From curiosity I counted the number of times I was called maquereau during the day, and it was thirty-nine.

A glimmer--one who watches vacant motor-cars.

Down and Out in paris

There is a camaraderie that comes from working long hours, from getting up with aching muscles, and a wool stuffed head from too little sleep. While in college I worked for a used bookstore that was the size of a grocery store. We were always understaffed, sometimes ridiculously understaffed. We needed three cashiers and generally had two. We needed three book buyers and generally had one. It wasn’t infrequent for people to work double shifts, not for the money, but because we couldn’t stand to think of our comrades left facing impossible odds. What was crazy is after we closed the store we would sit out in the parking lot, or when we could afford it go get a drink, and talk about books or about the craziness that happened during our shift until the wee hours of the morning. We were as bonded as soldiers in the trench because we were survivors. We didn’t bother to learn much about newbies until they had been there a month because chances were they would last a week or less.

We were working for $4 an hour.

A drop--money given to a beggar.

The endless stream of dirty dishes is truly an Orwellian nightmare.

While working in this fine restaurant Orwell did reveal some things that made me queasy.

”When a steak, for instance, is brought up for the head cook’s inspection, he does not handle it with a fork. He picks it up in his fingers and slaps it down, runs his thumb around the dish and licks it to taste the gravy, runs it round and licks again, the steps back and contemplates the piece of meal like an artist judging a picture, then presses it lovingly into place with his fat, pink fingers, every one of which he has licked a hundred times that morning.”

But the place of course is kept spic and span, right?

”Everywhere in the service quarters dirt festered--a secret vein of dirt, running through the garish hotel like the intestines through a man’s body.”

You may reassure yourself that restaurants are much better regulated now than they were in Paris in the 1920s and they are, but chat with a few people who work in the industry and it may not be as easy to reassure yourself.

A flattie--a policeman.

I always marvel at people that make a complete ass out of themselves berating a waiter in a restaurant. The distance that food must be carried from the cook to the table there is so much time for a waiter to enact some form of petty, but very satisfying revenge on some disrespectful jerk.

To knock off--to steal.

”Waiters in good hotels do not wear moustaches, and to show their superiority they decree that plongeurs shall not wear them either; and the cooks wear the moustaches to show their contempt for the waiters”…. Thus Orwell had to shave his moustaches.

Henry Miller was in Paris about the same time as Orwell. Miller wrote his books without worrying about what mommy and daddy might think. Orwell certainly put his remembrances through a strainer and certainly this book does not have the gritty intensity of a Miller novel. The descriptions of his time in the Paris restaurants are superbly drawn. They were certainly my favorite parts of the book. When he gets back to London he spends time tramping through the various charity houses and reveals the absurdity of the way they are run. He also makes a compelling case for changing the public view of who a tramp really is. A quick, enjoyable read, that for me, brought back some surprisingly fond memories of when I REALLY worked for living; and yet, still walked the razor edge of weekly impoverishment.

***3.75 stars out of 5 -

Down and Out in Paris and London, George Orwell

Down and Out in Paris and London is the first full-length work by the British author George Orwell, published in 1933.

It is a memoir in two parts on the theme of poverty in the two cities.

The first part is an account of living in near-destitution in Paris and the experience of casual labour in restaurant kitchens.

The second part is a travelogue of life on the road in and around London from the tramp's perspective, with descriptions of the types of hostel accommodation available and some of the characters to be found living on the margins.

عنوانهای چاپ شده در ایران: «محرومان پاریس و لندن»؛ «آس و پاس ها»؛ «آس و پاس در پاریس و لندن»؛ «آس و پاس ها در لندن»؛ «بیخانمانهای پاریس و لندن»؛ «فقر و دربدری در پاریس و لندن»؛ نویسنده: جورج اورول؛ تاریخ نخستین خوانش روز بیست و یکم ماه جولای سال 2006میلادی

عنوان: محرومان پاریس و لندن؛ نویسنده: جورج اورول؛ مترجم: اسماعیل کیوانی؛ تهران، تیسفون، 1362؛ در 318ص؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، مصدق، سال1395؛ در 248ص؛ شابک 9786007436554؛ موضوع داستانهای نویسندگان انگلیسی - سده 20م

عنوان: فقر و دربدری در پاریس و لندن؛ نویسنده: جورج اورول، مترجم: علی پیرنیا؛ تهران، ممتاز، 1362؛ در 318ص؛

عنوان: آس و پاس ها؛ نویسنده: جورج اورول، مترجم: اکبر تبریزی؛ تبریز، انتشارات بهجت؛ چاپ اول و دوم 1362؛ چاپ سوم 1385 در 269ص، شابک: ایکس - 964667190؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، بهجت، 1389؛ شابک 9789642763474؛ چاپ دیگر 1394؛

عنوان: آس و پاس ها؛ نویسنده: جورج اورول، مترجم: آوینا ترنم؛ تهران، ماهابه، هنر پارینه، 1394، در 286ص؛ شابک 9786005205558؛ چاپ سوم 1396؛

عنوان: آس و پاس در پاریس و لندن؛ نویسنده: جورج اورول، مترجم: عاطفه میرزایی؛ تهران، نشر پر؛ 1397؛ در 272ص؛ شابک9786226041140؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، باران خرد؛ 1397؛ در 288ص؛ شابک 9786226199049؛

عنوان: آس و پاس در پاریس و لندن؛ نویسنده: جورج اورول، مترجم: بهمن دارالشفایی؛ تهران، نشر ماهی؛ 1393؛ در 237ص؛ چاپ دوم و سوم سال1395؛ چاپ چهارم1396؛ شابک 9789642091942؛ چاپ پنجم 1397؛

عنوان: آس و پاس در لندن؛ نویسنده: جورج اورول، مترجم: فهيمه مهدوی؛ تهران: محراب دانش؛ 1398؛ شابک 9789642758531؛

عنوان: آس و پاس در پاریس و لندن؛ نویسنده: جورج اورول، مترجم: محبوبه ناصری؛ ساری آنوشا مهر؛ سال 1398؛ در 284ص؛ شابک9786227092158؛

عنوان: آسوپاسهای پاریس و لندن؛ نویسنده: جورج اورول، مترجم: زهره روشنفکر؛ تهران، مجید، 1388؛ در 240ص؛ شابک 9789644531118؛

عنوان: بیخانمانهای پاریس و لندن؛ نویسنده: جورج اورول، مترجم: علی منیری؛ تهران، ناژ، 1390؛ ��ر 234ص؛ شابک 9789641740926؛

داستان «آس و پاسها در پاریس و لندن»، روایت نویسنده ی «بریتانیایی»، «جورج اورول»، از زندگی فقرا، و بیخانمانها در «پاریس»، و «لندن» است؛ این کتاب در ماه ژانویه سال 1933میلادی منتشر شد، و در انتشار آن برای نخستین بار، جناب «اریک آرتور بلر» نویسنده، از نام مستعار «جورج اورول»، سود بردند؛ «اورول» پس از خوانش «تهیدستان جک لندن»، به زندگی در میان طبقات محرومان، و مهاجران، در شهرهای «پاریس» و شهر «لندن» علاقمند شدند؛ رویدادهای زندگی آمیخته با فقر ایشان، در بهار 1928میلادی، در مسافرخانه های «پاریس»، و اشتغالش به ظرفشویی، در رستورانها و هتلهای «پاریس»، فصلهای نخست این روایت را، شکل میدهد؛ راوی در بخشهایی از زندگی خویش در «پاریس»، با یک افسر پیشین «روسیه»، به نام «بوریس»، همراه میشود، که به سختی زندگی خویش را میگذراند، و از صاحبخانه ی «یهودی» خویش ناراضی است؛ برخی به همین دلیل، این کتاب را «یهود ستیزانه» میدانند؛

گزارش ایشان از «لندن»، بیشتر شرح روزگار بیخانمانهای کشور «انگلیس» است، که در پی یافتن بستری برای خوابیدن، از نوانخانه ای، به نوانخانه ی دیگر، رانده میشوند، یا شبها را، در پیاده رو خیابانها، میگذرانند؛ «اورول» این نوع زندگی را، برای نگاشتن گزارشی، در روزهای پایانی سال1927میلادی، تجربه کرده بودند؛ نکته ی تاثیرگذار این روایت، بر خلاف نظر همگان، این است که همه ی بیخانمانها، اشخاص بیعار، یا پست فطرت نیستند، و در بین آنها هنرمند، و روشنفکر نیز، میتوان پیدا کرد؛ در پایان کتاب «اورول»، پیشنهادهایی برای بهبود زندگی تهیدستان، و بی خانمانها ارائه میکنند؛ ...؛

تاریخ بهنگام رسانی 16/08/1399هجری خورشیدی؛ 31/06/1400هجری خورشیدی؛ ا. شربیانی -

this book isn't going to cause anyone to have the huge revelation that "poverty is hard!" or anything, because - duh - but it also doesn't piss me off the way morgan spurlock pisses me off, because orwell makes his story come alive and there is so much local color, so many individual life stories in here that this book, despite being horribly depressing, is also full of the resourcefulness of man and the resilience of people that have been left by the wayside. it is triumphant, not manipulative.

i liked the part when he was down and out in paris better than the part he was down and out in england. even though he had a handy exit strategy in england, in the form of someone who was willing to lend him money when he was truly and completely broke, and even though he only had to live the tramp's life for a month in england before his job started, the english parts were just so much more dismal, so horrifyingly bleak.

in paris, poverty is almost a lark. the accommodations are better, the homeless are allowed to congregate beneath bridges and these is almost a romantic tinge to being penniless.

england is just grim. flat-out grim.

big ups to orwell for his details - the smells and the disease and the horror of unwashed men being forced into cramped quarters are unfortunately very well-rendered and can be quite sickening at times. and the conditions of fine parisian restaurants at the time... shudder. don't read this while you are eating.

but this book will make you want to eat, truly. the days without food, the dizziness, the suffering. i ate like a hog on sunday, and felt very guilty for doing so while reading this, but it left such a hollow in me, i had to fill it somehow.

and - yes, this book was somewhat fabricated, and is like thoreau "in the wilderness," but that doesn't make orwell's observations any less legitimate or powerful.

thank you for writing such a fine book, george orwell...

come to my blog! -

في كتب بتقرأها عشان تقييماتها عالية..

وفي كتب بتقرأها عشان شخص تثق في ذوقه رشحها لك..

وفي كتب ، إسم كاتب معين علي غلافها بيكون كفاية إنك تقرأها ومن غير حتي ما تفكر..

متشرداً في باريس ولندن من النوع الأخير...

جورج أورويل- غني عن التعريف أكيد- كاتب وصحفي بريطاني ،من أشهر وأهم أعماله رواية ١٩٨٤ و رواية مزرعة الحيوان..

الروايتين دول-في رأيي-لو قريتهم مستحيل إنك تقدر تنساهم..

متشرداً في باريس ولندن تختلف كتير عنهم..مش بس كونها رواية عادية ولكنها أيضاً رواية مفيهاش أفكار كتير مهمة بس طبعاً يجب أن نضع في الحسبان إنها أول رواية طويلة للكاتب..

الرواية عبارة عن مذكرات شخصية لأورويل-مقسمة إلي جزئين-الجزء الاول بيتكلم فيه كيف كان يعيش حياة المتشردين في باريس لدرجة إنه إضطر أن يعمل غاسلاً للصحون في أحد الفنادق ..و الجزء الثاني بيحكي عن ظروف قاسية جداً مر بها في لندن و كيف عاش لأسابيع بدون مأوي ،ينتقل من مكان لأخر يبحث عن طعام وعمل بدون جدوي..

أورويل في الرواية بيلقي الضوء علي شكل أوروبا بعد الحرب العالمية الأولي وعلي حياة المتشردين و ما يواجهوه من صعوبات و في جزء من الكتاب بيفكر ويطرح بعض الحلول لمشكلتهم..

الجزء الأول في الكتاب كان ممتع وحتحس إنه حقيقي،واقعي جداً و حتي ساخر أحياناً ولكن جاء الجزء الثاني ممل ولم يضف الكثير للكتاب..

الصراحة الكتاب عادي وبعيد تماماً عن مستوي كتب أورويل الأخري و لولا إسم أورويل عليه أظن إن مكانش حد أهتم به أساساً..

تقييمي له كان حيكون نجمتين فقط لولا بس إنها تجربة شخصية صعبة مر بها الكاتب وإتكلم عنها بشجاعة ووضوح بجانب إني أستمتعت بقراءة الجزء الأول وكان فيه تفاصيل 'لذيذة' عن ما يحدث في مطابخ المطاعم والفنادق حتخليك تفكر ألف مرة قبل ما تاكل برة البيت..ودي لوحدها كفاية إننا نديله نجمة زيادة:)) -

Orwell demonstrates his social conscience and empathy for the poor, which I think, makes his more famous attacks on totalitarianism more credible.

This is also an interesting novel to read for a glimpse into Paris and London of that time, between 1900 and 1930. Orwell worked in some restaurants and his view from the kitchen is far less romantic than Hemingway’s perspective from the table.

Not really a classic or a masterpiece, but a book that should be read.

-

Orwell’s take on destitution was every bit as good as I expected it to be: beautifully phrased, meticulous, honest, funny, but also moving, and along with his own vivid experiences of living a hand to mouth existence he blends the testimonies of other refugees and homeless people in Paris and London. This book might not have even come about had it not been for a thief who pinched the last of an ailing Orwell’s savings from his Paris boarding room in 1929, thus leading him to search for dishwashing work in the kitchens of the French capital. Yes Paris was indeed a tough place to find shelter between the wars and even though Orwell eventually found a job at the anonymous Hotel X, a place where dirty roast chickens were served, and chefs spat in soup, he remained without pay for ten days and so was forced to sleep on a bench until he had enough to cover rent. Throughout the book, when he did manage to find somewhere to stay, some of the beds even had blocks of wood for pillows.

“The Paris slums are a gathering-place for eccentric people – people who have fallen into solitary, half-mad grooves of life and given up trying to be normal or decent. Poverty frees them from ordinary standards of behaviour, just as money frees people from work,” he wrote then, although his sympathies were firmly with his fellow “beggars”.

The book both illuminates the huge change between 1933 and now and exposes horrifying similarities. As Orwell reveals the cruelty of a lack of workers’ rights, where livelihoods are lost overnight or jobs not secure from one day to the next day, a modern audience cannot help but hear the words ‘zero hours contracts’. Job insecurity is still a major driver of homelessness nearly 90 years later. When in London Orwell describes the police arresting rough sleepers or ‘moving them on’, he foreshadows recent events such as the cleansing of the streets of Windsor before the royal wedding, and fines presented to beggars in Coventry. As he describes “the stories in the Sunday papers about beggars…with two thousand pounds sewn into their trousers” we can hear the headlines from this very year in a national newspaper proclaiming “fake homeless are earning £150 a day”.

Orwell’s books, however, are more than just treatises aiming to right the political wrongs. Aside from his political intentions, much of Orwell’s appeal has always rested in his brilliance as a writer: his ability to distil vast ideas or injustices into the most perfect phrases, his descriptive passages artfully conjuring the slum backstreets of 1930s Paris, and his sense of the preciousness of humanity, bringing clarity and colour to people's lives. through all all the filth, dirt, and smelly bodies, Orwell writes here and there with small moments of beauty, that at first don't feel immediately apparent. And when he writes of the people he meets in Down and Out are “just ordinary human beings”, he is stating a simple and obvious fact – but one that, even today, is still too often forgotten.

Of the two cities, I found the London half of the book the more interesting as I know less about the English capital than I do Paris; through my own knowledge and that provided by countless other writers nothing surprised me. Although it had it's funny moments, the seriousness of poverty really makes you sit up and take notice. This is just of an important book now as it was back then. A must read. -

İ´ve read the Essay “Paris Ve Londra'da Beş Parasız” written by George Orwell. It´s a biography of his own life and personal experiences. After George Orwell´s cancellation as officer of the British colonial power, he flew to Paris to work as an English teacher, because he aspired a job as a committed writer. Unfortunately his job as an English teacher and writer didn´t worked out and consequently he worked as a day labourer, harvester and dishwasher in a luxury restaurant. “Paris Ve Londra'da Beş Parasız” isn´t about political emphasises and has principally an anecdotic character. However this biography shows and emphasises clearly the former living environment of the entirely poverty stricken lower classes. It´s questionable if the business of those big hotels is still the same after 70 years, as Orwell describes. But yet this biography is very enriching and motivates the reader to think about this personal story.

-

Do not read this book while eating! I've been told that this book is semi-autobiographical. If so, George Orwell had an even more interesting life than I'd imagined! This book was disturbing, insightful and also funny (great, great characters, some just plain weird!)

The first half of the book depicts the main character's experiences living in poverty in Paris.Some of the descriptions about the living and working conditions are quite gruesome. All those bugs! Orwell sheds more light on what it must feel like to be poor; the ennui etc.I don't think I'll be able to eat at a Parisian restaurant anytime soon because now I'm a little paranoid about the cooking conditions.

The second half of the book finds the protagonist back in London and we learn more about what it means to be a "tramp." Equally as disgusting descriptions as those in the Paris section, especially the part where several tramps had to use the same bucket of dirty water for cleaning themselves up, yuck!

Orwell definitely puts a human face on the tramps. He explains how tramping is a huge social problem and then suggests how this problem can be remedied. As I live in Vancouver, the Canadian city with the highest number of homeless people, I agree with his explanations and thoughts.

My only gripe was with this particular edition of the book. Way too many typos, both in English and in French. Also, they censored out some of the swear words, bizarre.

Fantastic book! Orwell rarely disappoints me with his wit and insight. -

Είναι αυτό το καλύτερο βιβλίο του Όργουελ; Μάλλον όχι, αφού μιλάμε για τον συγγραφέα του ‘’1984’’ και της ‘’Φάρμας των Ζώων’’.

Είναι αυτό ένα βιβλίο που κλείνοντάς το νιώθεις πως έχεις πάει ένα βήμα παραπέρα την σκέψη σου, έχεις καλλιεργήσει την κοινωνική σου ενσυναίσθηση και έχεις πάρει απαντήσεις σε ερωτήσεις (δυστυχώς ορμώμενες από προκαταλήψεις) που είχες και εσύ ο ίδιος; Σίγουρα ναι.

Όταν θα είστε σε ένα βιβλιοπωλείο, αν τύχει και ξεφυλλίσετε το συγκεκριμένο βιβλίο, ρίξτε μια ματιά στα κεφάλαια 22, 36 και 38. Όλες οι περιγραφές της αθλιότητας, των στερήσεων, τη βρωμιάς, της φτώχειας, του εξευτελισμού, της εκμετάλλευσης και της εξαθλίωσης που περιγράφονται στο βιβλίο αποσκοπούν στην διατύπωση των προβληματισμών που αναπτύσσονται σε αυτά τα κεφάλαια.

Πρόκειται για μια ιδιαίτερη μείξη δημοσιογραφικής έρευνας, ημερολογιακής καταγραφής, αυτοβιογραφικών στοιχείων και κοινωνικού σχολιασμού. Ο Όργουελ περιπλανιέται στο Παρίσι και το Λονδίνο του Μεσοπολέμου, την περίοδο που η ανεργία θερίζει, και παρέα με άλλους εξαθλιωμένους από τη φτώχεια συνοδοιπόρους του, πασχίζει να εξασφαλίσει κάθε βράδυ ένα κατάλυμα να κοιμηθεί, πολλές φορές μένοντας νηστικός για ως και πέντε μέρες και υποφέροντας ανυπέρβλητες στερήσεις.

Πολιτισμένος λαός δεν είναι αυτός που ακούει όπερα, διαβάζει ψαγμένα βιβλία, ψυχαγωγείται βλέποντας ταινίες του Ταραντίνο και του Κιούμπρικ και συγκινείται από πίνακες και έργα τέχνης στις γκαλερί, αλλά ένας λαός του οποίου το πιο φτωχό στρώμα ζει σε ανθρώπινες συνθήκες, με αξιοπρέπεια και χωρίς να στιγματίζεται σαν επαίτης.

Εκ πρώτης όψεως μοιάζει με ένα άχαρο βιβλίο (πόσο γοητευτικό μπορεί να είναι ένα βιβλίο που πραγματεύεται τη φτώχια και την εξαθλίωση;!), όμως κλείνοντάς το προβληματίζεσαι και μένεις να αναρωτιέσαι πόσο εύκολα η τύχη όλων μας μπορεί να αλλάξει από τη μια μέρα στην άλλη. Όπως λέει και ο Μακεδόνας στο γνωστό τραγούδι :

‘’…Γι' αυτό κάτσε καλά

κοίτα λίγο χαμηλά

η ζωή κατρακυλάει, μη λες πολλά’’.

Κλείνω με ένα απόσπασμα από το βιβλίο που αποτελεί τροφή για (πολλή) σκέψη:

‘’Πράγματι, αν φροντίζει κανείς να μην ξεχνά ότι ο αλήτης δεν είναι παρά μόνο ένας άνεργος Άγγλος, που ο νόμος τον αναγκάζει να ζει περιπλανώμενος, τότε ο <<αλήτης-τέρας>> πάει περίπατο. Δεν ισχυρίζομαι βεβαίως ότι οι περισσότεροι αλήτες είναι ιδανικοί χαρακτήρες. Υποστηρίζω απλώς ότι είναι φυσιολογικές ανθρώπινες υπάρξεις και ότι, αν είναι χειρότεροι από άλλους ανθρώπους, αυτό είναι αποτέλεσμα και όχι αιτία του τρόπου ζωής που ζουν. Συνεπώς, η αντίληψη <<τα θελαν και τα παθαν>>, με την οποία αντιμετωπίζονται συνήθως οι αλήτες, δεν είναι πιο δίκαιη απ’ ότι θα ήταν απέναντι σε ανάπηρους ή ασθενείς’’. -

آس و پاس در پاریس و لندن,اولین رمان موفق جورج ارول=اریک ارتور بلر(نام حقیقی,به علت ترس از بی ابرویی موقع چاپ این کتاب از نام مستعار جرج ارول استفاده کرد!)

توی این کتاب بدبختی و فقر طوری هنرمندانه و حقیقی به تصویر اومده که خواننده رو به خنده میندازه,و این نهایت قدرت یه نویسنده ست!

این اثر طبق زندگی جرج ارول هست..و واقعا غیر از این نیست که یک نویسنده پشت در های بسته نمیتونه کتاب بنویسه..و قدرت قلم یک نویسنده وقتی از واقعیت زندگی منشا میگیره است که بر جان مینشینه.

این اثر و دختر کشیش,بیشتر قابل حس و لمس در زندگی روزمره اند..و بنظر من پارت بیشتری از روح نویسنده رو در خودشون دارن.. -

Kako da se udam za vojnika, kad ja volim čitav puk?

Odavno nešto originalnije nisam pročitao kada je u pitanju glad, iznurenost i trula bijeda. Napisati knjigu sa dvadeset devet godina koliko je tada Orvel imao kada je ona objavljena i da stranice prosto klize, da rečenice imaju punotu opipljivog i da suptilno prilaze izrabljivanju i radu i uopšte društvenom kretanju kao takvom, za mene nije mala stvar. Roman me dosta podsjeća na rečenicu s početka filma Los Olvidados, Luisa Bunjuela, u parafrazi: “Skoro svaka prestonica kao Njujork, Pariz, London krije, iza svog bogatstva, siromašne domove gdje su slabo uhranjena djeca, lišena zdravlja ili obrazovanja, osuđena na kriminal...Meksiko, veliki moderan grad, nije izuzetak ovog pravila.“

Orvel ne budi vjeru u iznenadnost nastanka nečega čudesnog i velikog niti da elementima slijepog nereda i zanosnog nespokoja pokuša da čitaoca baci u iluzornu pojavu savršenog. U Parizu je akcenat stavljen na rad, dok se u Londonu Orvel više koncentriše na skitanje i beskućnike. Koliko god bijeda bila loša, Orvel joj pristupa kao okviru u kome jedinku prožima olakšanje, pa gotovo i katarza što se nalazi na dnu. Njegova budućnost je poništena i njega kao takvog obuhvata ravnodušnost. Pri tome ovo nije jednostavno jer treba izdržati gladovanje i dosadu, i da još imaš na umu da si zaista u bijedi, da nemaš kuda. Orvel je pokušao da pronađe kopču koja bi bila zajednička za ono što se naziva “normalan rad“ i “pristojan život” ali on je samo nailazio na ogroman međuprostor te dvije sintagme te da bi mogućnost odsustva prekomjernog rada samo ugrozilo bogataševu sloboda: “Zato imućniji ljudi samo i govore o poboljšanju uslova rada, života itd…” Čini se da je ovo zaista jedan beskompromisan roman pa svidilo se to nekome ili ne, on vojuje za veće dostojanstvo i veći značaj čovjeka. -

“It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out. You have talked so often of going to the dogs — and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it.”

While best known for 1984 and Animal Farm, George Orwell is a fantastic essayist. In Down and Out in Paris and London, he chronicles the struggles of those barely getting enough to survive. At the time, that included our narrator/a fictional version of George Orwell. The narrator details his own trajectory as he slides into near starvation. Orwell approaches this slide from a psychological perspective that was both fascinating and a punch in the gut. In the last section of the book, Orwell discusses his ideas for alleviating this extreme poverty.

“If you set yourself to it, you can live the same life, rich or poor. You can keep on with your books and your ideas. You just got to say to yourself, "I'm a free man in here" - he tapped his forehead - "and you're all right.” -

تجربة حياتية ثرية مر بها الكاتب الكبير في بدايات حياته ذاق خلالها مرارة الجوع والحاجة مما كان له كبير الأثر في فكره وشخصيته لباقي حياته.

في الجزء الأول رأيت الجانب المظلم والبائس من باريس الماثلة أمامنا دائما كنموذج مثالي للجمال والرقي. ذلك الجانب المظلم الذي عاصره أورويل بحكم اضطراره إلى التنقل بين مختلف الوظائف الدنيا في بداية حياته.

ينزع أورويل عن مطاعم باريس والتي عمل بها كغاسلاً للصحون قناع الرُقي والفخامة الذي طالما سمعنا عنه، ونكتشف أن خلف هذا المظهر البراق للطبق الباهظ الثمن مطبخا قذرا لا يراعي أدنى قواعد النظافة.

لا أريد أن أثير غثيان من يقرأ المراجعة، ولكن أورويل لم يقصر في وصف الكواليس الخلفية لتلك المطابخ ولا عن ظروف العمل المفزعة لمن يعملون بها في وقت اقامته في نهاية العشرينيات.

في الجزء الثاني يعود أورويل إلى وطنه إلى لندن على وعد بالتحاقه بوظيفة ذات مرتب محترم وقد ظن أنه وجد بها مخرجا من حياة الجوع والبؤس التي ذاقها في باريس. ويفاجأ بتبخر تلك الفرصة لدى علمه بسفر أصحاب تلك الوظيفة.

يضطر للجوء إلى عيش حياة التشرد ونرى معه أيضا ما يختبئ خلف مظهر المتشرد الرث القذر المثير للشفقة.

يتعرف المؤلف على نماذج عدة للمشردين وعلى الأسباب المختلفة التي رمت بهم إلى رصيف الشارع. وكيف يتحايلون على ظروف حياتهم القاسية بالسرقة مرة وبالتسول مرات. ويجرب الحياة في ملاجئ الإعالة للمشردين والتي لا تختلف كثيرا عن أرصفة الشوارع القذرة.

في نهاية تلك التجربة يخلص أورويل بأن حل مشكلة مشردي الشوارع ليست في مجرد محاولات الحكومة المفتعلة لإطعامهم غث الطعام-واتحدث هنا عن بريطانيا في الثلاثينات من القرن الماضي- ولكن في محاولة استغلال طاقتهم في الأعمال التي تكفل لهم طعامهم مثل الزراعة. إذ أن أورويل قد خلص إلى أن معظم من اعتاد حياة التشرد لن يرضى بأن يلتزم في عمل يقيده. ولكنه من الممكن أن يكلف بأعمال ذات طبيعة مؤقتة أو بسيطة تؤمن الحد الأدني من الأدمية لهم.

الترجمة كانت مليئة بالكلمات الصعبة. كما نقل المترجم العديد من المصطلحات الأجنبية كما هى بدون أن يحفل بترجمتها. وكان ذلك هو مأخذي الوحيد على الكتاب. -

The film Midnight in Paris begins with some beautiful scenes of Paris: the Louvre, Notre Dame, the Seine, the Sorbonne, the Eiffle Tower, the arc de triomphe. And before long, arrives a parade of artistes from the 1920s milieu - Hemmingway, Bunuel, Dali, etc, - all speaking *SparkNotes*. But in the distant background (very distant) I hear a faint sound of et in arcadia ego and Orwell protests “say, I was there in the 1920s too - I saw all that. And I wrote a damn fine book about it”.

That book is Down and Out in Paris and London, written later on in England (he wrote 2 books while in Paris but he destroyed them after one rejection. He regretted doing that).

If I were to take a stroll, à la “Midnight in Paris”, I might find myself on 6 rue du Pot de Fer, 1928:

‘Salope! Salope! How many times have I told you not to squash bugs on the wallpaper? Do you think you’ve bought the hotel, eh? Why can’t you throw them out of the window like everyone else? Putain! Salope!’ The woman on the third floor: ‘Vache!’

Quarrels, and the desolate cries of street hawkers, and the shouts of children chasing orange-peel over the cobbles, and at night loud singing and the sour reek of the refuse-carts, made up the atmosphere of the street.

It was a very narrow street—a ravine of tall, leprous houses, lurching towards one another in queer attitudes, as though they had all been frozen in the act of collapse. All the houses were hotels and packed to the tiles with lodgers, mostly Poles, Arabs and Italians.

At the foot of the hotels were tiny bistros, where you could be drunk for the equivalent of a shilling. On Saturday nights about a third of the male population of the quarter was drunk. There was fighting over women, and the Arab navvies who lived in the cheapest hotels used to conduct mysterious feuds, and fight them out with chairs and occasionally revolvers.

At night the policemen would only come through the street two together. It was a fairly rackety place. And yet amid the noise and dirt lived the usual respectable French shopkeepers, bakers and laundresses and the like, keeping themselves to themselves and quietly piling up small fortunes. It was quite a representative Paris slum.

No Peugeots here. Orwell was not living a glamourous life. He had recently thrown away a promising career in Burma, and was determined to make it as a writer or die trying.

He published a few articles, but soon runs out of money and must find work. He takes a job (as a foreigner, “not seriously illegal”) washing dishes at the luxury hotel Lotti in 1929. That experience is the ‘Paris’ segment of the book.

He returns to England at the end of the year and “tramps” around with the down and out for the ‘London’ part.

The lifestyle of a tramp was unhealthy and mean. One "ate cat's meat, and wore newspaper instead of underclothes, and used the wainscoting of his room for firewood, and made himself a pair of trousers out of a sack".

It is boring, "a tramp's sufferings are entirely useless. He lives a fantastically disagreeable life, and lives it to no purpose whatever."

It is exhausting, "he had not eaten since the morning, had walked several miles with a twisted leg, his clothes were drenched, and he had a halfpenny between himself and starvation."

And it is no fun, "tramps are cut off from women".

On the bright side, "poverty frees them from ordinary standards of behaviour, just as money frees people from work."

“It is altogether curious, your first contact with poverty. You have thought so much about poverty—it is the thing you have feared all your life, the thing you knew would happen to you sooner or later; and it, is all so utterly and prosaically different.

You thought it would be quite simple; it is extraordinarily complicated. You thought it would be terrible; it is merely squalid and boring. It is the peculiar lowness of poverty that you discover first; the shifts that it puts you to, the complicated meanness, the crust-wiping.”

The first version of Down and Out is completed by Oct 1930, under the name George Orwell (used for the first time, to protect his upper lower middle class parents). The French translation La Vache Enragée is published in 1935.

Orwell’s inspirations for this book, indeed this life:

The Lower Depths

Maggie, a Girl of the Streets and Selected Stories

The People of the Abyss

The Road

The Life of Mr. Richard Savage, Son of the Earl Rivers

Germinal

Themes:

impoverishment, failure, privation, penury, leftovers, overextended, pennilessness, beggary, pauperism, difficulties, reduced circumstances, hunger, lack, want, dearth, depletion, exhaustion, vacuity, meagerness, dogged, indigent, impecuniousness, need, hardship, suffering, misery, dirt, filth, grime, lowness, grunge, muck, dust, rats, bugs, vermin, trapped, penury, destitution, greasiness, smelly icky slums, vagrancy, exiguity, mendicancy, down, out, crust-wiping, and all things squalid -

Quite a harrowing book,with its depiction of stark poverty,menial work and the constant struggle for the basic necessities of life .

I found it hard to read,but it was very moving as well. Orwell also did a similar job in another book,The Road to Wigan Pier. That too,was very bleak and compassionate.

Orwell knew about hardship.He had given up his job in the imperial police,and things were not too bright for him financially. He actually became a dishwasher for a while. He lived that life,he could talk about it with authenticity.

It's been some years since I read it,it stays in memory.But I'd find it difficult to read again,it's too raw and realistic. -

What I learned from this book (in no particular order):

1. There is hardly such a thing as a French waiter in Paris: the waiters are all Italian and German. They just pretend to be French to be able to affect that certain hauteur and charge you exorbitant prices for that mediocre Boeuf Bourgignon.

2. Some of them are spies. Waitering is a common profession for a spy to adopt. It is also a popular profession among AWOL ex-soldiers and wannabe snobs.

3. Real scullery maids do “curse like a scullion” (hey, that’s a Hamlet quotation!). No doubt Shakespeare had watched a real-life Elizabethan scullion at work.

4. Men cooks are preferred to women, not because of any superiority in technique, but for their punctuality in delivering orders. The only woman cook featured in the book has nervous breakdowns at exactly 12 pm, 6 pm and 9 pm every day, although it must be noted that they are caused by circumstances that are beyond her control.

5. A French cook will spit in the soup --- that is, if he is not going to drink it himself. He is an artist, but his art is not cleanliness. To a certain extent he is even dirty because he is an artist, for food, to look smart, needs dirty treatment.

6. A steak will not be handled with a fork: the cook will just pick it up in his fingers and slap it down, run his thumb round the dish and lick it to taste the gravy. He will further press it lovingly with his fat, pink fingers, every one of which he has licked a hundred times that morning. When he is satisfied, he takes a cloth and wipes his fingerprints from the dish, and hands it to the waiter.

7. And the waiter, of course, will dip HIS fingers into the gravy --- his nasty, greasy fingers which he is forever running through his briliantined hair.

8. The scullery is the filthiest part of all: it is nothing unusual for a waiter to wash his face in the water in which clean crockery is rinsing.

9. The Plongeur is the lowest kitchen worker in a French restaurant who deals with the dirtiest, sweatiest work available. However, he is allowed two liters of wine a day, because otherwise, he will steal three. Everyone seems to work faster when partially drunk anyway.

10. A bum’s life, whether in Paris or London, is a real BUMMER.

BUT SERIOUSLY,

George Orwell went slumming in Paris and London, and the result is probably one of the best-written accounts of the bumming life ever penned. However, don’t read it if you are sensitive to pungent, unsparing descriptions of filthy kitchens, foul body odors, bug-infested beds and other unsavory aspects of a life gone to the dogs. -

.. رواية رائعة ظلمتها شهرة ابنة أبيها البارة "1984" فهي الرواية الأشهر لجورج أورويل بلا منازع.

• «هنا العالم الذي ينتظرك إن كنت مفلسا في أحد الأيام..»

• تتناول الرواية حياة البائسين بصدق وتدقيق من عاش في تلك الدروب المظلمة من باريس ولندن ..

•بعد قراءة الرواية سوف تعيد التفكير قبل الدخول إلى فندق راق لتناول الطعام، وقبل أن تنتظر كلمة شكر من متسول أعطيته بنسا..

_ أمر آخر، إذا زرت لندن ولم تجد متسولين ينامون في الشوارع كما في باريس فالأمر ليس مؤشرا طيبا.. إنما هي القوانين التي تجبرهم على المبيت في أماكن تعد الشوارع غاية في الراحة بالنسبة لها ولا يمكنه المبيت في نفس المسكن اكثر من مرة في الشهر فبالتالي يقضي المتشرد أغلب عمره على الطريق مجبراً لتجنب للسجن..

_ هنا الوجه المشوه لشوارع باريس ولندن فعلى الجانب الآخر من مطاعمها وفنادقها الفاخرة لا يفصلك إلا باب مزدوج عن البؤس الحقيقي لحياة غاسلي الصحون اليائسة لا هدف من هذه الحياة ولا مستقبل لها ، فلا يملك غاسل الصحون ترف التفكير لما هو أبعد من وجبة طعامه وإيجار نُزله..

«البؤس هو ما أشرع أكتب عنه، البؤس الذي اتصلت به للمرة الأولى من حياتي، في هذا الحي الفقير... كان للوهلة الأولى درسا موضوعيا مادة دراسية للبؤس وصار فيما بعد خلفية تجاربي الخاصة، ولهذا السبب أحاول أن أقدم فكرة ما، عما كانت عليه الحياة هناك»..

قبل نهاية الرواية يقول جورج أورويل « أشعر بأنني لم أعرف من البؤس إلا حافته .!». . -

از اول تا آخر كتاب، انگار در حال پيادهروي بودهاي.. يك پيادهروي مداوم در كوچهپسكوچههاي پاريس و لندن.. نه از آن پيادهرويهايي كه باعث شوند گذرت به بخشهاي خوب و رمانتيك و لذتبخش شهر بيفتد... برعكس.... انگار روزها در محلههاي كثيف و مملو از فقر و فلاكت قدم برداشتهاي... و شبها را همراه و همگام جورج اورول، در غيرقابل تحملترين مسافرخانهها و اقامتگاههاي پاريس و لندن، به صبح رساندهاي..

همه اين كتاب، روايت فقر است.. نكته دلنشين و برجسته كتاب اين است كه اولا نه از زبان يك فرد گمنام، بلكه از جانب نويسنده 1984 و مزرعه حيوانات، روايت ميشود.. و بيان جزئيات قضايا و توصيفهاي اورول، تو را هر چه بيشتر و بيشتر در صحنهها و اتفاقات داستان غرق ميكند.. در كنار اين مضمون، لحن اورول كه در قسمت زيادي از بخشها، آميخته به طنز است، اين هنر را دارد كه در غمانگيزترين توصيفات داستان هم تو را به خنده بيندازد... يكي از بهترين بخشهاي كتاب هم، آنجاست كه اورول از شخصيتهاي فقير و خيابانخوابي در داستان اسم ميبرد كه برخلاف تصور عموم كه آنها را بيارزش و تنبل و بيمصرف ميدانند، از فكر و هنر و ويژگيهاي شخصيتي جالبي برخوردارند...

در ضمن، ترجمه (بهمن دارالشفايي) هم عالي بود.

***

بعد از غذا، بوريس آنقدر خوشبين بود كه تاحالا اينطور نديده بودمش. گفت: چي بهت گفتم؟ تقدير جنگ! امروز صبح پنج سو داشتيم. حالا وضعمان را ببين! هميشه گفتهام بدست آوردن پول از هر كار ديگري آسانتر است. همين الان ياد دوستي افتادم كه در خيابان فونداري است. بايد برويم و ببينيمش. مردك دزد چهارهزار فرانك سر من كلاه گذاشته. وقتي هشيار است، بزرگترين دزد روي زمين است. اما نكته عجيبش اين است كه وقتي مست ميكند كاملا صادق است. فكركنم ساعت شش بعدازظهر ديگر مست شده باشد. احتمال زيادي دارد كه عليالحساب صدفرانك بدهد. شايد هم دويست فرانك بدهد. بزن بريم!

به خيابان فونداري رفتيم و طرف را پيدا كرديم. مست بود، ولي پولي به ما نداد. همينكه بوريس و او همديگر را ديدند همانجا در خيابان دعواي لفظي سختي بينشان درگرفت. آن مرد ادعا ميكرد كه يك پني هم به بوريس بدهكار نيست. بلكه اتفاقا اين بوريس است كه چهارهزار فرانك به او بدهكار است. هردوي آنها مدام رو به من ميكردند و نظرم را ميپرسيدند. من آخرش نفهميدم حقيقت ماجرا چه بوده. بعد از اين كه دوساعت تمام، همديگر را دزد خطاب كرده بودند، از من جداشدند و دوتايي رفتند ميگساري... -

First published in 1933, this was George Orwell’s first full length book which made it into print. Although it reads as though the events within it were concurrent, in fact much of the latter part of the book was published as an essay, titled, “The Spike,” while the author was in Paris. However, the fact that events do not necessarily follow the narrative, certainly does not invalidate the book, or the points that Orwell makes – sadly still very valid today.

The first half of the book sees Orwell in Paris. Although certainly not flush, he does not experience poverty until his meagre savings are stolen. Orwell’s aunt was, as we now know, in Paris at the time – although we do not know whether she helped him financially. Whether she did or not, it is certainly that he did experience financial hardship and that this led him to taking up work as a lowly dishwasher in hotels and restaurants. The scenes of hotel life are so vividly written that you have no problem imagining the organised chaos, sheer filth and wonderfully exotic characters that exist within the pages. Paris, at that time, had a huge Russian émigré population and Orwell is befriended by Boris, a Russian refugee and waiter. Through him, Orwell embarks on arduous attempts to find work. When work is finally obtained, the seventeen hour days, exhaustion and grinding work is offset by the possibility of eating regularly. Some of the characters in the Paris section of the book work so long that they seem trapped in kitchens and hotels around the city. If you go out for a meal after reading this book I will be very surprised!

In the book, Orwell returns to England after finally being driven to write to a friend to help him find work. When he arrives in London, he is lightly told that his employers had gone abroad for a month, but “I suppose you can hang on till then?” Of course, things did not happen quite this way – as we know, the London part of the book was written before the Paris section. Orwell was later to insist that the events within the book had taken place, albeit not in the order they are written here and it is not necessarily important that a little artistic tension is used to give the storyline a little tension.

The London section of the book sees Orwell living as a tramp in London. A real down and out, tramping from one hostel, or ‘spike’ to another. He shows the reality of that life – of being forced to move on constantly, because of rules which refused a man a bed two nights running, the way the tramps were forced into prayer meetings for a cup of tea and a bun, of their resentment and discomfort, of laws which meant the police could move tramps on if they were asleep and the general discomfort and filth they lived with.

This is moving journalism, which really presents a vivid portrait of a life on the edge. As Orwell points out, when funds are low panic sets in. When there is nothing, there is just existence from one meal to the next. He makes many valid points about how the poor are treated and how their life could be improved. Having just read a news report which suggested that so many people in Britain are reduced to using food banks due to problems with their benefit payments and punitive punishments, you have to sadly conclude that his conclusions about the treatments of people living in poverty are still more than valid. -

Instagram ||

Twitter ||

Facebook ||

Amazon ||

Pinterest

I was inspired to read this book after picking up and enjoying

A MOVEABLE FEAST by Ernest Hemingway, which was a beautifully written memoir of living in Paris as a broke writer in the 1920s. I didn't even think I liked Hemingway as an author until I read that book and was totally blown away by the vivid descriptions of the "lost generation" working on many of their magna opera that would make them famous-- in the case of F. Scott Fitzgerald, posthumously so. DOWN AND OUT IN PARIS AND LONDON is Orwell's memoir of being a broke writer in the 1930s and it is... well, vivid, yes, but not in the fun way. More like in the visceral doom-scrolling way that so many of us are accustomed to in Our Year 2021.

There are two parts to this book. It opens with Paris, which in some ways does glamorize poverty, I feel. Or maybe that's just because Paris is more livable to those in dire straits. He paints comical portraits of his landlords and fellow tenants, and of his co-workers at the hotel at which he worked as a dishwasher. This was my favorite portion of the book because it feels the most light-hearted-- he has some cunning observations on the poor versus the rich, on the hypocrisies of society, and a few cunning tips on how to even the odds as someone who has the odds stacked against them. Unfortunately, this is also the part of the book that is rife with antisemitism. Given the time at which this was published, it was not shocking to excuse it, but the zeitgeist does not excuse the fact that many of his comments would be wholly inappropriate today, even if it makes it easier to understand why he says and thinks the things he does. Apparently, Orwell came to question many of his harmful beliefs later in life in his journals (he was an ardent diarist) and if that is the case, it is glad news, because history is filled with creators who have messed up some way ethically and rather than introspect and seek to be better people, they have simply doubled-down and closed their ears.

The London portion, as others have pointed out, is much starker and far more grim. There is a description of a lodging house that is truly horrifying. The characters he meets in this portion are also interesting but I feel like they didn't have the verve of the people he met in the Paris portion, and Orwell himself seems so much more exhausted here. The work is harsher and less forgiving, people seem so much more jaded, the conditions are draconian, etc. I also found it to be more repetitive and skimmed some portions, although I did like his chapter where he lists out some of the "cant" he observed among people working the streets, and meditates on slang, appropriated words, and Cockney dialect.

Whether you like or hate Orwell (and there are reasons to feel either way), I think this is a fascinating insight into his life, and there were several events that seemed to inspire his two major works, 1984 and Animal Farm (particularly his observations on how the working class is exploited and basically worked to the bone while the rich pretend to care but don't). The first portion of the book is like hearing about that one "bro" friend of yours recount travel to a questionable location while staying in a dangerous hostel. The second portion of the book is like hearing about that same "bro" friend recounting a terrible ordeal. The tonal shift between the two portions is noticeable and even though it affected my reading, it really made the book feel raw and real in a way that some of these literary figures sometimes don't because so much time has passed that their personalities feel removed from their work.

Anyone who enjoys edgy memoirs or learning more about literary figures will enjoy this.

3 to 3.5 stars -

This reminded me a bit of Thoreau's Walden in that you don't feel like Orwell had to go through with this. It's self-imposed deprivation. However, while Thoreau went on a camping trip to prove he was a hardy outdoorsman and that anybody could and should do it, Orwell put himself through his ordeal in order to investigate a situation. The same problem exists in both circumstances though. Both men could extract themselves at any time if they wished. In Orwell's situation, that means he was only experiencing the details of being poor, not fully feeling the all-but inescapable confinement of being destitute. Knowing you can't get out of a situation has a deleterious affect on one's outlook and actions.

Having said that, Orwell gets as close to the real thing as probably possible in Down and Out in Paris and London. Throughout much of the narrative, he's living hand to mouth with only the clothes on his back for possessions. The going is tough and made tougher by the prejudice people show towards a tramp.

But Orwell's a good storyteller with plenty of tales to tell. His characterizations of some quite colorful characters are a joy. So, while this topic can get heavy at times, there's enough lighthearted fun within these pages to make the reading fairly even.

Because parts of this book were admittedly embellished and other parts are clearly a factual account, it's hard to know how to shelve this and it's not always easy to trust what you're reading. I want to say that it's obvious what's real and what isn't, but seeing how some people fall hard for fake news these days, I'm hesitant to label anything "obvious". -

George Orwell is a damn good writer. Sure, he whipped out 1984 and Animal Farm, but it's from his essays and nonfiction that I'm learning Orwellian tricks--and by that I mean, the very best sort of craft points.

Yes, I know that his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) is characterized as a novel--usually with some qualifier like "semi-autobiographical" or "thinly-veiled." But given that Orwell saves several chapters for his personal commentary about, among others, the life of a Paris plongeur, London slang and swearing, tramps, sleeping options for the homeless in London, and the Salvation Army, it seems a stretch to me to use the word "novel." I understand his book to, at most, have about as much inevitable fudging as a memoir.

DOPL is about exactly that--Orwell mired in poverty, looking for work or working 17-hour shifts in hellfire hot hotel kitchens, begging, pawning, banding together with others in the same state, starving, and generally fighting to survive.

The temptation would be to lay it all out there--"This happened, and then this happened, and then this happened....." Orwell doesn't fall for it. Rather, he uses anecdotes proportionally: the shorter ones add scope and breadth to what might otherwise be read as an individualized experience; longer ones push the narrative forward; still longer ones fundamentally shape Orwell's experiences and opinions. With narrative intention for each sub-story, Orwell keeps the book from being a diary-esque dumping ground for every interesting thing that happened to him. He allows each story only as much it needs to serve its textual purpose. Given proper weight, the story of the weeping cook in the bad restaurant is as compelling as that of Boris, the former Russian army captain now sleeping in bug-infested sheets in the slums--even though we spend significantly more time with Boris than the cook.

What's the point? Why wouldn't a diary-esque series of observations be just as compelling? If DOPL took this travelogue route, it'd still have worth. But because Orwell takes pains to shape a narrative, one with continuity even when he leaps into another country and set of characters midway through, readers are prepared for the chapters when Orwell's first-person narrator turns discursive.

Why don't we resent the narrator for getting all political on us in the midst of a good story? Orwell refrains from opining in scene, saving it up for discursive chapters placed at natural pauses. The first discourse doesn't appear until the narrator is transitioning between Paris and London. We readers want to reflect before we make that leap; otherwise, it'd be too abrupt. The discourse actually builds tension, because while we know the narrator is steaming towards London, with one chance to pull himself out of dire straights, he's not there yet. The discursive chapter delays the resolution and heightens suspense.

And finally, Orwell's plain-language voice is a stay against the resentment we might feel for a pontificating narrator. "For what they are worth I want to give my opinions on the Paris plongeur. ..." Nothing high and mighty in that tone; our guard drops. Rather than riddiling his commentary with adjectives, adverbs, and other grammatical efforts towards artificial emphasis, Orwell puts his money on nouns: facts, observations, and general good sense.

Which means he's following his own advice, from the essay he'd later write titled "Politics and the English Language." Not that I'm one for artifical emphasis, but it's only one of the best essays ever written, ever. -

I've loved everything I've ever read by Orwell, including this book which is very autobiographical "fiction", written in the first person. The temporal setting of the "novel" is sometime in the 1920s I think. This is actually not a bad book to sample Orwell with, of course nowhere near as famous as Animal Farm or 1984, but it reads much like a memoir (a very interesting one) and hence can be experienced as a sample of Orwell's writing style and views on society, without those things being masked by the futurist/fantasy plots of the more famous books.

-

سمعت الكتاب ده كـ audiobook وكان من أجمل التجارب اللي مريت بيها.

-

I read this right after finishing A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway; both are set in Paris in the 1920s, so I'm eager to compare the two and damn there's a lot to say. I feel like Orwell was much more genuine and really saw the greater scope of events and tried to show "the big through the small". So by showing his experiences in Paris and London he managed to showcase the universal reality of what it's like to be poor and destitute and what the reasons for poverty are.

It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out. You have talked so often of going to the dogs - and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it. It takes off a lot fof anxiety.

Before getting deeper into the analysis, I need to tell you how funny this book is. I've read some of Orwell's nonfiction but this is by far his most personal account. Usually, Orwell is very stingy with sarcasm and humour, but this time around we were really on the same page.

I am trying to describe the people in our quarter, not for the mere curiosity, but because they are all part of the story. Poverty is what I am writing about, and I had my first contact with poverty in this slum.

He met so many different and interesting people in Paris and the comic relief was quite high in most of these encounters. In one scene George talks about Fureux and how he always got stupidly drunk on the weekends and started singing The Marseillaise. Due to his patriotic fever, the other fellows in the bar started to tease him and shout "down with France" to get him all reved up. The whole scene in itself is quite hilarious but then George solves the scene in the funniest way possible by telling the reader that "In the morning he [Fureux] reappeared, quiet and civil, and bought a copy of L'Humanité" (a magazin that is quite left and not patriotic at all). I was hollering!

I really enjoyed that George included snippets of the french language in this because it added a great deal to the atmosphere and made it so easy to picture Paris with its hotels and people in the 1920s. Overall George spoke some great truths in this novel.

He was just so brutally honest about money and I found it admirable. It got me thinking about how much the times (and the currencies) have changed. ;) Some of the realities of the 1920s are impossible to even think about today.Six francs is a shilling, and you can live on a shilling a day in Paris if you know how. But it is a complicated business.

I loved how honest he was about being ashamed of being poor. And how he tried to hide it from the laundress, the hoteliers and basically everybody. He talked about how little he had to eat, that he could only wash himself once a month and was wearing practically the same clothes everyday because he sold the rest of his stuff. It is quite crazy to think about.

Eighteen hours a day, seven days a week. Such hours, though not usual, are nothing extraordinary in Paris.

Also, the idea that in the 20s a little chamber in a hotel was far cheaper than renting an appartment seems unreal to contemporary readers. He talks about the horrendous experiences he had with the people with whom he had to share his chambers with and how some of them "had the indecency to bring a woman in here, while I was there on the floor. The low animal!" Oh poor George!

Boris, a friend of George's who used to work in a hotel became George's closest companion on their hunt for a job, and he was also one of my favorite people in this account. He was quite a good sport and always remained optimistic throughout their streak of bad luck . Also, his humour was top-notch:'But what about the suitcase?'

I mean HOW GREAT IS THAT QUOTE. I'm getting serious Oscar Wilde-vibes from it.

'Oh, that? We shall have to abandon it. The miserable thing only cost twenty francs. Besides, one always abandons something in a retreat. Look at Napoleon at the Beresina! He abandoned his whole army.'

The only thing that I wondered about was George's sex life. Yeah, okay, that is a little weird but George seemed to live sex-less. He had no problem with talking about women and when one of his friends got laid but he himself didn't seem to be too interested in that. He was clearly averted to some homesexual approaches that he had to deal with but of a woman? no word.

In his London episode, he talks about the evils of a tramp's life and how the sexless life affects a lot of men who are poor and that they turn to homosexuality and some even rape woman to satisfy their needs. This, of course, is a very backwards and old-fashioned view on life with which I don't agree. I was appalled throughout by George's dislike for homosexuality and his need to find excuses for sexual abuse, but it was interesting nonetheless, to get this first-hand account of the past.

I was also quite shocked to see at how much wine they drank. And that people of their profession (dishwashers etc.) drank wine like water. It quite reminded me of Hemingway and his alcoholism. People at that time were really crazy in some ways.

I also enjoyed his commentary on the quite strict hierarchy existing in a hotel, and how he as a dishwasher was basically on the bottom—people who did the most strenous word, made the least money. He analysed the different forces that come into play in regards to money and power and how it influences society.

At the end of his Paris adventures he dedicates a whole chapter to the "social significance of a plongeur's life". He is brutally honest and speaks freely on how stupid this way of employment is:No doubt hotels and restaurants must exist, but there is no need that they should enslave hundreds of people. [...] Essentially, a 'smart' hotel is a place where a hundred people toil like devils in order that two hundred may pay through the nose for things they do not really want.

A little fun fact regarding waiters: George says that in some hotels/ restaurants waiters get sooo many tips that they actually pay the patron for their employment and they get paid no wages, they manage to live (quite excessively) off tips. That's crazy to think about!

Fear of the mob is superstitious fear. It is based on the idea that there is some mysterious, fundamental difference between rich and poor, as though they were two different races, [...] but in reality there is no such difference.

To sum up. A plongeur is a slave, and a wasted slave, doing stupid and largely unnecessary work. He is kept at work, ultimately, because of a vague feeling that he would be dangerous if he had leisure.

I won't talk too much about his London adventures because for me, it was all about Paris and the revelations George had there. His London episode was fun to learn about nonetheless. I had this odd realization that poverty (in a way) prevents loneliness. George was never alone at any time. He always found people (strangers basically) who shared his condition and always took him in, tried to make him one of their own. I find that quite fascinating.

I also really appreciated the times in which he compared Paris to London and how he had to accomodate certain aspects of his destitute life:In Paris, if you had no money and could not find a public bench, you would sit on the pavement. Heaven knows what sitting on the pavement would lead to in London - prison, probably.

One of the most interesting London chapter was the one in which he talked about beggars and why people hate them and don't think it's a real job.

I suppose they were 'nancy boys'. They looked the same type as the apache boys one sees in Paris.It is taken for granted that a beggar does not 'earn' his living, as a bricklayer or a literary critic 'earns' his. [...] If one could earn even ten pounds a week at begging, it would become a respectable profession immediately.

A chapter I found very charming and in which I could highly relate to George was the chapter in which he basically made a glossary of London slang, defining the words he wasn't familiar with before. It is just such a George Orwell thing to do and I loved it.My story ends here. It is a fairly trivial story, and I can only hope that it has been interesting in the same way as a travel diary is interesting. [...] At present I do not feel that I have seen more than the fringe of poverty. [...] I shall never again think that all tramps are drunken scoundrels, nor expect a beggar to be grateful when I give him a penny, nor be surprised if men out of work lack energy, nor subscribe to the Salvation Army, nor pawn my clothes, nor refuse a handbill, nor enjoy a meal at a smart restaurant. That is a beginning.

It is, George, it is. Down and Out in Paris and London is by far my favorite piece of nonfiction by Orwell. It's rich in social commentary and criticism and I'd highly recommend it to everyone looking for a raw and honest account of poverty in Europe's capitals in the 1920s. -

وقتی خوندمش که خودم آس و پاس در تهران بودم، پنج روز درگیر. سفری فراموشنشونده و کتابی که بهطرز جالبی با احساسات و افکار اون چند روزم آمیخت. منم تا پاریس و لندن آس و پاس شدم پی رویاهایی که مثل نویسنده داشتم.

کتابی از ارول که خیلیها نخوندنش ولی بهشدت توصیه میکنم، برای موقعی که آس و پاس بودید.

ریویوهای اینجا هم عالیان، پس منم فقط حسم رو گفتم. -

داستان این کتاب واقعی بود؟

باور نکردنی به نظر میاد!

برای اولین بار توی زندگی م، کتابم چرب شد؛ و الان فکر می کنم که اون لکه ی چربی، با فضای قسمت پاریس کتاب، کاملاً متناسبه. جورج اورول توی این کتاب از مدتی می گه که هیچ پولی نداشته و به پست ترین شغل ها و وضعیت زندگی تن داده تا بالاخره کار درست و حسابی ای پیدا کنه.

مسافرخونه های پر از ساس، لباس هایی که گرو گذاشته، روزهای متوالی که غذا نخورده یا خواب درستی نداشته، هتلی که آشپزخونه ش دستشویی یا آب گرم نداشته، رفقایی که زندگی های عجیب و غریب و طرز فکرهای خاص خودشون رو داشتن...

خیلی عجیب، دردناک، ماجراجویانه و هیجان انگیز بود. -

Five stars from me. I would use three words to describe this book: “somber, side-splitting, shrewd”. “Somber” refers to the subject matter, which is about abject poverty and hunger in urban cities, as seen through Orwell’s eyes in Paris and London on his experimental tour. “Side-splitting” is my reaction to the ironic and dry humor that he effortlessly displays in describing some episodes. “Shrewd” refers to his observation of the lives of those barely surviving in society’s lowest echelons, often down to the most trivial minutiae and with keen insight.

The book is a unique kind of partly fictional, semi-autobiographical, travel diary in which Orwell tells the experiences of a British writer working alongside plongeurs (dishwashers or scullions) in a Paris hotel kitchen, and then living with tramps (homeless people) upon his return to England. His description of the Paris hotel kitchen will make you think twice before stepping into a high-class hotel restaurant ever again!

These are some trenchant passages from the book:-

When one is overworked, it is a good cure for self-pity to think of the thousands of people in Paris restaurants who work such hours (seventeen-hour day, seven days a week), and will go on doing it, not for a few weeks, but for years.

I believe that this instinct to perpetuate useless work is, at bottom, simply fear of the mob. The mob (the thought runs) are such low animals that they would be dangerous if they had leisure; it is safer to keep them too busy to think……But the trouble is that intelligent, cultivated people, the very people who might be expected to have liberal opinions, never do mix with the poor. For what do the majority of educated people know about poverty?

Why are beggars despised? I believe it is for the simple reason that they fail to earn a decent living…. Money has become the grand test of virtue. By this test beggars fail, and for this they are despised.