| Title | : | Last Stories |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | - |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Kindle Edition |

| Number of Pages | : | 220 |

| Publication | : | First published May 15, 2018 |

Last Stories Reviews

-

These ten poignant stories are exquisite and instantly atmospheric, giving vivid glimpses of varied lives, often involving widows, widowers, or other solitary souls, who seem broadly content, but are contemplating what to do now. Many of the stories have two main threads that seem unrelated but come together.

The understated style reflects the importance of what is not, or cannot, be said in the stories themselves.

Secrets, whether deliberately kept or unconsciously buried, abound. Sometimes the past is revealed, but in other cases, the fear is enough. And some remain happy in their denial or ignorance.

Secrecy often implies victims, but several of these stories are deliciously ambiguous about whether there is a victim, and if so, which of the characters it is.

Reviews of individual stories (no spoilers)

1. The Piano Teacher’s Pupil, 4*

By the second page, I felt I’d known the piano teacher all my life: the arch of her story, and her quotidian regime. She’s the sort of single middle-aged woman who used to be called a spinster and for whom people feel sorry. But she’s sure she’s not unhappy, and is cheered by memories of happiness. And then a new joy: a brilliant new pupil, though there’s something a little odd.

“Each time after the boy left there was a mockery in the music that faintly lingered.”

She figures out the facts, but she doesn’t need to understand or hear any excuse. She’s the grateful recipient of genius.

Image: Porcelain swan - totemic in the story (

Source.)

2. The Crippled Man, 3*

The title set me on edge from the start, and word recurs throughout, but that fits the unsettling tone of the story. Itinerant brothers knock at the crippled man’s door, offering to paint the house, while his cousin-cum-carer is out.

“Wherever they were, they circumvented what they did not call the system, since it was not a word they knew.... Survival was their immediate purpose, their hope that there might somewhere be a life that was more than they yet knew.”

Nothing is clear: not (initially) to the reader, not to the painters whose English and maybe intelligence is limited, nor to the carer or the crippled man whose communication is also vague and sometimes veiled. Is the apparent ending the actual one? Read it and decide for yourself.

3. At the Caffè Daria, 4*

“What happens, Anita wonders, to people who walk away.”

The café has an origin story that could be a story in this collection in its own right: after WW2, a wealthy Italian, heartbroken by his wife’s leaving him for another man, ended up in London, and founded a stylish café in her memory. But that’s just the first two of twenty pages.

“He was seized, in desperation, with eccentricity: to do something to confirm his existence.”

The real story concerns a former dancer who’s been a regular customer since childhood, and her best friend from dance days. All three stories are linked by betrayal and women walking away.

“Childless women as they are, they might turn to one another now. But pretence’s truth is shoddy, without a heart. And the past is too far off, its laughter does not echo, its flimsy shadows fall away.”

4. Taking Mr Ravenswood, 4*

The opening sentence, a long, hanging-modifier garden-path one, demonstrates a great writer flouting the “rules”:

“Belonging to her time on the counters - before they removed her upstairs to Customer Care - Mr Ravenswood’s easy smile stirred in Rosanne’s memory, the paisley handkerchief tidily protruding from the top pocket of a softly checked jacket, the tweed hat on the counter for the duration of whatever transaction there was.”

What at first seems the chance of escapist respite from a life of second-best and failure, develops into a darker plan - or two. Who is preying on who?

“Guilt tells you about yourself.”

5. Mrs Crasthorpe, 4*

It opens with Mrs Crasthorpe’s “profound humiliation” as the sole mourner at her husband’s bleak funeral, in a village he requested, though she does not know why. But she’s a woman of secrets herself: buried so she can rise in the world.

Her journey through grief and attempting to forge a new life is contrasted with that of Etheridge, a man whose path occasionally crosses hers, though he wishes it didn’t. Nevertheless, he’s a gentle man and a gentleman. He can keep other people’s secrets.

6. The Unknown Girl, 3*

A young woman steps into traffic and is killed. Who is she? There is an answer of sorts, but it tells us almost nothing. She is indeed unknown, and was perhaps unknowable.

7. Making Conversation, 4*

This one is almost humorous, as two women discuss how they perceive their relationship with a man who is largely off-stage. One unreliable narrator (if so, which?), or two?

8. Giotto’s Angels, 4*

Image: Giotto’s Angels in The Lamentation (

Source.)

“When privately he considered his life - as much of it as he knew - it seemed to be a thing of unrelated shred and blurs, something like the damaged canvases that were brought to him for attention.”

A picture restorer with severe but intermittent amnesia makes for a different sort of unreliable narrator (not that he actually narrates the story). He has various tricks and routines to navigate life, but it’s not easy, and he’s therefore vulnerable. I was reminded a little of Ogawa’s The Housekeeper + The Professor (see my review

HERE).

“A memory came to him in the way it sometimes did, emerging from nowhere but very clear… [but] he couldn’t hold it. Slippery like some old snake it was.”

I loved and believed the portrayal of Constantine Naylor, but I didn’t quite believe in the other person in the story (how they justify their actions, and what they (nearly) do at the end).

9. An Idyll in Winter, 4*

“Often their thoughts touched before words expressed them.”

A 12-year old girl has a 22-year old male tutor living with the family over the summer in a fairly remote northern farm. Inevitably, the Brontes come to mind (even before he says the moors are “Very Heathcliffian”), and inevitably Mary Bella develops a crush on Anthony, but the story itself develops in unexpected ways.

10. The Women, 5*

Cecilia is 14, has always known her mother is “not here”, but despite a good relationship with her father, is not sure if that means she left or died, but “she lived with her uncertainty”.

On the advice of friends, Cecilia’s father sends her to boarding school, “to be a girl among other girls”. She hates it at first, settles in, and the story progresses in a somewhat simplistic boarding-school story style, reflecting Cecilia’s youth. The women of the title are fully formed but initially mysterious figures, and Cecilia’s reactions are in character. It’s hard to explain why I thought this story was the best of the set, but perhaps the closing paragraph gives an idea:

“The flimsy exercise in assumption and surmise crept, unsummoned, into Cecilia’s thoughts and did not go away. Shakily challenging the apparent, the almost certain, its suppositions were vague, inchoate. Yet they were there, and Cecilia reached out for their whisper of consoling doubt.”

Quotes

“She read the novels that time’s esteem kept alive, and judged contemporary fiction for herself.”

“There was excitement in the shadowlands of what might have been.”

“Suppositions were vague, inchoate. Yet they were there, and Cecilia reached out for their whisper of consoling doubt.”

“Television was something for an audience of more than one.”

“His continuing anger at the careless greed of death.”

“Obedient to her vanity, the grey in her hair was softened in an artificial way, her skin was daily cared for, its small ravages patiently repaired.”

“His eyes… had a most look, suggesting a residue of tears, and yet were not quite sad. It was more sentiment than sorrow.”

Why this, why now?

I first read William Trevor four years ago: a haunting novel, The Story of Lucy Gault (see my

HERE). I intended to read another, but during coronavirus pandemic, I’m drawn more to short pieces, so when Laysee wrote a sublime review of these stories (

HERE), I knew now was the time.

A little background

Julian Barnes shared

this insight from his late wife, Pat Kavanagh, who was Trevor’s long-term literary agent:

“He liked to sit on park benches and eavesdrop on conversations; but that he never wanted to listen to a whole story, so would get up and move on as soon as he had heard the small amount he needed to trigger his further imaginings.”

These “last stories” were apparently written as a collection and found by his son as a completed manuscript after his death, aged 88, in 2016. However, many of them had been published in The New Yorker, some as much as ten years earlier. -

I've only recently started reading this author, feel in love with his stories, his writing which always shows so much compassion. In this collection, his last, he shows how people fare after life's betrayals, often highlighting loneliness and loss. Some are rather grim, but show a marked insight into the frailty of us all.

I enjoyed all of these, but my three favorites included the first story, The Piano Teachers Pupil. In this story a woman, now in her fifties, considers herself fortunate but is also lonely. She feels a sense of genius skating from the playing of this young man. He has an unfortunate habit though, one that costs the teacher a few material items, but she feels the illicit trade is well worth it as long as she can keep hearing his playing.

The others I liked were a rather grim Mrs. Crasthorpe, two lives that barely intersect will prove unforgettable for one, but in a rather sad way. There was just something in the melancholy tone in which this was written that appealed. I also enjoyed An Idyll in Winter, I felt this was the most compassionatly written of them all, as it would be so easy for us to judge and criticize the male character in this one.

I may have come to this author late, and am sad that he is gone, but I do have many of his books still to savor. That is something in which to look forward. -

The elation of having read an outstanding short story collection defies description. How often do we stumble on a collection where every story is a gem? Last Stories is a posthumous collection of ten stories by William Trevor published in 2018. In his lifetime, Trevor, a prolific Irish writer, wrote 4 novels, 2 novellas, and 13 collections of stories. When he died in November 2016 at age 88, the world lost a true master of the short form. I read each of these last stories slowly, savoring as it were, literally, the final words of a beloved author.

The characters in Last Stories are lonely people who have been widowed or abandoned, and are trying to make the most of their solitary existence in as dignified a manner as possible, but not always succeeding. In The Piano Teacher’s Pupil, a piano teacher in her fifties, disappointed in love, finds exhilaration in the exceptional talent of a shy, young pupil even though she quickly fathoms why he is shunted from teacher to teacher, and chooses to ignore the truth. Passion and deception rest side by side. In Mrs Crasthorpe, a near 60-year-old woman whose elderly husband has died, confessed to marrying him for his money. There is something spunky in her confidence that she is still a rosebud with irresistible charms: "I shall relish my widowhood... I shall make something of it.” A vulnerable man who recently lost his wife becomes the object of her quest. Will she succeed? The interior life and emotional struggles of these women and other characters are similarly laid bare in a mere few pages.

Trevor has a knack of revealing delicately bit by bit the secrets of his characters and their flaws. Mrs Crasthorpe has a past unbeknownst to her husband that returns to blackmail her. In The Women, Cecilia, an adolescent girl who is well loved by her father grows up with no knowledge of her mother and assumes she has died. Years later, stalked by two strange women, she begins to piece together the truth surrounding her father’s marriage. In Taking Mr Ravenswood, Rosanne, a bank teller, catches the fancy of Mr Ravenswood, a rich widower, and is badgered by her boyfriend, to swindle Mr Ravenswood. Neither Rosanne nor Mr Ravenswood is as straightforward as s/he seems, and it is hard to tell who has the upper hand. With Trevor, stories are so subtly told one is never quite sure what to make of the ending. Interestingly, the ambivalence is not annoying but oddly satisfying.

Quite a few of these stories have an unnerving or unsettling edge to them, which reminds me of the creepy novel, The Children of Dynmouth. Many times I felt uneasy or anxious for the characters. In The Crippled Man, two foreigners were hired to paint the house of a crippled man who lives with his female cousin. The latter provides care and housekeeping with the hope of perhaps one day inheriting the house. The characters do not say much to each other and choose to listen selectively when they do. The foreigners understand little English and speak little of it too. So they ignore and pretend not to hear what is spoken, including arguments, between the crippled man and the woman. However, much is communicated in the silence that fills the spaces in between their limited words, especially when the conversation in the house stops completely signifying all is not well. In The Unknown Girl, a cleaner who works for Harriet, a widow, and her young adult son dies in a traffic accident shortly after she abruptly fails to show up for work. Harriet recalls with discomfort a flash of what passes as some dalliance between the deceased and her son. There is powerful writing here that suggests there is more than meets the eye. In Giotto’s Angels, a picture restorer who suffers from bouts of amnesia, struggles to find his way home to his warehouse where he works and lives. He is poor and vulnerable, yet this does not spare him from being the target of a prostitute who has designs to strip him of his last farthings. But she has a heart and I hoped for the best. How foolish of me to expect good outcomes in Trevor’s world!

Suffice to say, Trevor wrote with superb authorial control. In Last Stories, Trevor saved the best for last. In all of these stories, Trevor’s empathy and deep compassion for his characters is inspiring. This, to me, is the mark of a very fine writer. -

William Trevor's Last Literary Gems, or Jengas

Review — 5/28/2018

I discovered William Trevor several years ago when listening to the “The New Yorker: Fiction” podcast, from 12/10/07, when Jhumpa Lahiri chose and read Trevor's short story "A Day." You could say, it blew me away. Since then, I've bought and read most of two other of his collections.

Trevor's mastery is not in prose or "structure" in the literary sense of the word. He is a maestro in constructing a story that reveals some human emotion or ice-shattering effects of our homocentric interactions. One way to describe this might be that he erects a Jenga tower of some human condition nudging the reader toward an ending that takes her breath away like a) pulling out the wrong block and all falls down, or b) removing just the right one, leaving her in awe at Trevor's perfection.

Trevor's final focus, in his Last Stories, seems primarily on the deception and various varieties of betrayal, and its short- and long-term adverse effects on betrayer, betrayed and those collaterally damaged, and the harm done by one's inability to cope with disappointments flowing from high expectations. As examples, a father's betrayal by deception of a daughter who in turn attempts to betray herself by self-deception; a betrayal borne of pity of a woman without a family or friends; out of pity arises a man's betrayal of his family and an ironic lesson in the pain and cost of unrequited love; how a double betrayal by husband and best friend leads to a betrayal of self and humanity in the black heart of vengeance.

In "Giotto's Angels," which overlies a Dante Eighth Circle special betrayal, Trevor captures the reader with a tale (a bit allegorical possibly) of good versus evil, beauty versus ugliness.

Probably the best of the brilliant bunch is "An Idyll in Winter," in which a married man visits the farm estate of a girl who had fallen head over heels for him when he tutored her maybe ten years in the past. The story delves into the devastating fallout from adultery, but moreso from the girl's inability to accept that love cannot be perfect (maybe especially so for love once unrequited and for love on which a betrayal of another is built), it will not stay a winter white idyll, which leads to the biting and ironic self-rationalization: "...she only wishes the men could know that love unchanged is as it was, is there for him among her shadows, for her in rooms and places as familiar to him as they are to her. She wishes they could know it will not wither, that there'll be no long slow dying, or love made ordinary."

Highly recommended. If you're on the fence about William Trevor or his talent, I suggest you listen to Jhumpa Lahiri read his short story, "A Day."

https://www.newyorker.com/podcast/fic...

I've got it on my list to read all of his stories. The literary world has lost a great one. -

Thank You Laysee for inspiring me to read these short stories:

Ten in all:

1 The Piano Teacher’s Pupil

2 The Crippled Man

3 At the Caffè Daria

4 Taking Mr. Ravenswood

5 Mrs.Crasthorp

6 Mrs. Unknown Girl

7 Making Conversation

8 Giotto’s Angels

9 An Idyll Winter

10 The Women

The first story - “The Piano Teacher’s Pupil”, gives us much to chew on. Mrs. Nightingale is a single woman in her fifty’s. She has lived in the same house since she was a child- raised by her now deceased father who was a chocolatier.

We learn that she never married - but wanted to - and was in love ( having an affair), with a married man for sixteen years.

We also learn about the young boy, her piano student, ‘from’ what Mrs Nightingale ‘tells’ us. She knew her pupil was a musical/piano genius from his first lesson...from the moment the boys fingers touched the keys.

Each week after the boy’s lessons - ( or perhaps performance), Mrs. Nightingale notices an item from her house is missing....

Her reactions - are puzzling.

I don’t want to give the rest of this short story away....

but it left me with much to think about....

We learn more THOUGHTS from Mrs. Nightingale’s ABOUT her father - ABOUT her her affair- ABOUT the prodigy pupil.

SOMETHING WAS *REALLY* MISSING FOR ME about this story....

ALL THAT WASN’T written is what fascinated me most. The layers below the surface are not clear.

In every situation - Mrs. Nightingale is so PASSIVE - SO ACCEPTING - SO SUBMISSIVE - SO REMOVED FROM HERSELF - SO FRAGILE- I COULD’T find her authentic voice. I also never really understood her.

Yes....this woman was lonely - but also- I wondered WHY?

And....

.....she never once left her house - was she an agoraphobia? If so, what was the cause of her feelings of unworthiness?

Honestly- this story was very unsatisfying! There was no transformation or clear insights. It felt like a very unfinished story to me.

Oh my....I could write a full page - easily on each story....

I’d be swimming upstream for both myself and for any of you who are reading this. I’d actually ‘like’ too write about each story....( but these are unsettling days - where I’m also trying to balance my online time carefully) —

THESE STORIES - written well—were unsettling- most didn’t feel uplifting or with any resolutions ( sounds like current life)....

I’ll attempt to sum up my thoughts - feelings - and experience of having read William Trevor for my first go around ( and sadly his last published book before his death at age 88).... rather than review each story.

.....

This collection *is* as great as any book I could choose to pick for a book group discussion...( emotions triggered and all - juicy discussion opportunities in these stories)...

There is much to chat about from these stories.....with a GRAND LOOK AT THE HUMAN PSYCHE:

...complex vulnerable characters....who are lonely, fragile, ....filled with disappointments, passing smiles, professionally polite, broken souls, living in broken cities, with broken relationships.

Deception, assumptions, humiliations, misconceptions, infatuation’s and romance,reflections, oppressions, observations, desperation’s, desires, love, loss, grief, struggles, loneliness, death, a little pretending, courage, hesitations, a little humor.... and unresolved ‘mysteries-of-life’, embodied these stories.

Hidden gems....are SENTENCES- that the reader must hunt down - then pocket for keepsakes.

It’s not that ‘all’ of William Trevor’s prose isn’t bittersweet-beautiful....

But the chocolate flavored cherries...are hiding. Each story has at least two or three of these yummy cherries 🍒 to pick & pocket.

Me..., besides the many pause & ponder moments, I enjoyed the simple ordinary things.... a croissant from Caffe Daria...with a cuppa coffee....listening in on others conversations. ( naughty human curiosity prevails)...

Or.... Dancing with Fireflies....

Or...giggles with old school chums.

Overall ... these stories kept my thinking engaged.

Subtle power was always brewing .

I’m happy to have had my first introduction - with the talented - respected - much loved author - who seems to have been loved by many readers around the world.

I look forward to trying another William Trevor book! -

"But pretences truth is shoddy, without a heart"

What an amazing feeling to have a writer's words resonate so strongly with you from the opening sentence. That's how I felt with this book.

"Last stories" simply blew me away.

I'd not heard of William Trevor before. It's only from reading Laysee's eloquent and heartfelt review that my interest was piqued. Short stories? Yes, I'm in. William Trevor? Hmmmm. Not a name I'm familiar with. But I'm happy to find out more. WOW. These stories spoke to me. They have a slow, drawn out poignancy, that will hit you where it hurts. In fact, the poignancy aches off the pages.

The characters are flawed. But in saying this, we are all flawed in different ways. The are often lonely; this seems to be a running theme throughout the stories. There's a need for company. They live ordinary lives. They are ordinary people. The stories and the characters are haunted by their memories. Whatever point they are at, whatever they are about to do, the past is always there. Their companion. Even when they are looking forward, they are still looking back. I can't say that any of them are particularly happy. Perhaps resigned to their fate. But this does not make for an upsetting book. Instead, this makes for a book that will really reach in and make you take stock of your emotions, and apply what these characters are feeling to your own experiences and life.

Oftentimes a short story collection will be uneven, with some stories not quite hitting the mark. I didn't find that here at all. They each captured my attention and my heart for different reasons. There was such a lilting quality of longing in them. The want for...something more.

But I wouldn't be honest if I did not admit that one did in fact stand out more, that shone more brightly. At the Caffe Daria is utterly exquisite. It is worth borrowing/buying or downloading the book for this story alone. It is the most stunning story of a friendship lost between two women over a shared lover. And the impact he still had on their lives so many years later. Sublime.

"She doesn't mind being alone. She did once, but doesn't now, and supposes that being alone has become part of her, as mornings at the Caffe Daria have too."

"Deception is confessed: the attractions of an attractive man come at a price."

"She opens drawers and finds them empty. She reaches into shelves for what might be at the back. There is no handbag or purse. There is no note: the open door said all there was to say. What happens, Anita wonders, to people when they walk away. What then do they become?"

After one full week of working from the "home office", I openly concede to getting more than a touch of cabin fever. Not to complain, as so many are going through so much more, But it's been hard. Strange times.

I'd had my fill of electronic devices. Group chats, phone meetings, video calls, the landline ringing, the mobile incessantly pinging. The noise in my head was loud. So on Saturday, I turned them all off. Not just to vibrate or mute, but off. I spent the day immersed in this gem of short stories. And it was so good. To get back to basics, not be distracted, and just read. For the simple joy of getting lost in a good book. I cannot remember the last time that I did that. Sometimes the right book finds you at the right time.

Shout out to Laysee! Thank you for your wonderful review, as it brought to my attention a "new" Author to discover and love. This was something special.

Please read Laysee's fab review at

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show..."

I definitely want to find out more about William Trevor, this amazing writer. His life. Who he was. I went into this collection completely blind and purely on reading Laysee's review. So my knowledge of him is zero. I very much want to discover what other gems he has written. It's been a long time since I devoted a day to a book.

5 bursting stars ✩✩✩✩✩

I truly hope that whoever hasn't read William Trevor before will be enticed to read this. Whether or not you're a fan of the short story genre, this book will leave its mark. -

A reckoning of life in quiet, somber snippets. Individuals who are alone, but not necessarily lonely. A man with a groggy memory, another who is simply inadequate, people who have accepted their lot in life. Loved the passage that spoke of a person's death; with his or her passing, a tale that has been told. And that history lives forever. Treat yourself to ten small helpings of slice of life stories with a melancholy feel.

-

I bought this book at a literary festival event in May. The event was a celebration of what would have been William Trevor's 90th birthday had he lived, and it consisted of panel discussions on his work, and readings from a few of the stories in this collection - which were all found among the author's papers after his death.

While waiting for the event to start, I read through one of the stories, The Piano Teacher's Pupil, and therefore was perfectly tuned in for the first reading - The Piano Teacher's Pupil.

I'll never forget that story now - the reading was such a fine performance and the story itself is like a distillation of all his stories: nostalgia for a lost time but with a little twist at the core. -

4.5

I learned after reading the first story of this collection that it was the last written by Trevor. It may seem slight, but only in comparison with his other writings, a high bar. On the way to my favorite story, the exquisite, disquieting, penultimate one, we are treated to stories of people alone, not necessarily lonely, some merely surviving, not truly living; characters whose lives intersect in complex, often unspoken, ways, sometimes provoking empathy in another, even over a tiresome person; surface lives so different from inner ones.

Well-worn themes are different in Trevor’s hands. He stands them on their head. In one story, it’s not that the characters can’t communicate; it’s that their lack of doing so is intentional. Simple sentences are not throwaways; all is important. Ambiguity forces the readers to acknowledge that what they don’t know is also unknowable to the characters, and is not the essential thing.

The endings are sublime, their words devastating. And of course they are because of all that came before. -

Okay I have no idea what happened with these short stories. The writing felt bland and nonspecific, the plots nonexistent, the characters indecipherable and vague. It seemed to me that the author practiced restraint to the point of literally nothing happening, event-wise or character-wise.

I don’t really have more to say about this short story collection so I will recommend some other short story collections I have greatly enjoyed:

Unaccustomed Earth by Jhumpa Lahiri,

Sour Heart by Jenny Zhang,

Hunger by Lan Samantha Chang,

You Are Not a Stranger Here by Adam Haslett, and

Home Remedies (specifically “Vaulting the Sea”) by Xuan Juliana Wang. Check them out and let me know what you think! -

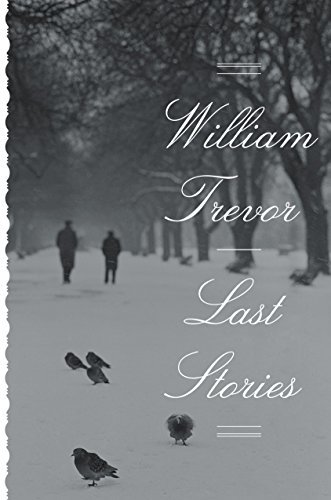

This is a book that you can freely judge by its cover, because the stories inside are just as lovely and wistful as the wintry scene on the front. In fact, this was an unplanned read - of a series of short stories no less, something that I mostly shy away from - that I picked up solely because I was drawn to the way it looked.

As the first thing I’ve read by William Trevor, I found it to be an unexpected treat. While these are not the happiest of stories, they evoked feelings in me that I recognized at a very deep level. I think this is where Trevor’s gift is; telling these profoundly human stories, showing us to be the selfish, deceitful, lonely, vulnerable, and lovable creatures that we are. I think there is something in here that will resonate will almost every single reader, whether they’re willing to admit it or not.

True to what I feel the nature of a short story must be, each of these begins in a place about which you know very little. I enjoyed that feeling of dawning realization as the stories unfolded, sometimes a subtle feeling, other times more abrupt. It’s easy to make assumptions about where you think the author is taking things but trust me, he will not make it that easy for you!

If I had to pick a favorite in this collection it would be An Idyll in Winter, which encompasses so many different reactions and emotions that I could relate to, that it warrants a second reading someday. And after the serendipitous discovery of these stories, I’ll be searching out previous works by the sadly, recently deceased William Trevor. -

Vinnicombe

Si sente spesso parlare di capolavoro, quel tale film, quella serie, quel romanzo, quel racconto, quell’azione che ha portato al gol, quel tweet, come se ne avessimo un bisogno vitale. Quasi inquietante. Di solito i capolavori, almeno alcuni di loro, non si notano, passanti che non hanno niente di speciale, non ricordiamo i vestiti, il nome, l’andatura.

Oggi ho riletto due racconti di William Trevor (1928-2016) pubblicati postumi, nel 2018, e da noi quest’anno da Guanda, col titolo “La ragazza sconosciuta”. Per me questa raccolta è un capolavoro, non lo dico con l’entusiasmo “del libro dell’anno” perché so che Trevor non finirà mai tra gli autori di prima pagina, dell’anno, del mese, del giorno, spesso è arrivato finalista in molti premi. Non ha mai vinto. Trevor ad alcuni non piace, è così, o meglio, tutti capiscono la sua bravura ma la prima reazione quando viene letto, è ‘niente di speciale, storie di vita quotidiana, persone di mezza età, amori mancati, finali che non rapiscono’. Tutti vogliono essere rapiti, scossi, esaltati. Se invece ci soffermassimo sulla singola riga, sulla singola situazione capiremmo che Trevor è un fuoriclasse del momento rivelatore, dell’istante che contiene una vita, e allo stesso tempo è un fuoriclasse nel lasciarlo disperdere, quel momento. Per questo Trevor si attira delusioni. Critici improvvisati che lo trattano con degnazione. Trevor è uno scrittore che ha raggiunto la perfezione migliorandosi fino agli 80 anni; ad alcuni sembrerà strano ma un racconto di venti pagine è difficile, terribilmente difficile. È un fatto tecnico.

Un racconto si intitola “Per fare conversazione”, è lungo 19 pagine ma per un occhio attento bastano le prime 4, lette con cura, per capire che Trevor è un maestro. Non nel senso che lui insegna e noi impariamo, no, lui è bravo e noi non lo siamo altrettanto.

Una donna, si chiama Olivia e ha 37 anni, sta vedendo una serie tv, suonano al citofono. Una signora, circa cinquantenne, dice di essere la moglie di un certo signor Vinnicombe. Crede che suo marito, sparito da giorni, si trovi in quel posto, a casa sua. A questo punto Trevor torna indietro al giorno in cui Olivia, uscendo da un colloquio di lavoro, inciampa sul marciapiede e un signore di passaggio la sorregge. È un tipo come tanti, un po’ grassoccio, lei lo ringrazia con calore. La vicenda finisce lì, per lei. Ma per lui no. Questo fatto banale, si insinua nella mente di Vinnicombe come un assillo, quello è il colpo di grazia, l’amore fatale. Si incontrano di nuovo dopo qualche tempo in un bar caffè. Vinnicombe si ripresenta, lei lo aveva già dimenticato. Inizia a dire che è un inventore, a lei vengono in mente strani inventori del passato, da Leonardo a Edison, no no, lui è un inventore di oggetti casalinghi, cose come bacchette elettroniche per aprire e chiudere le finestre. Lo dice con enfasi. A questo punto esatto il lettore di Trevor ha capito, lo sente, lo avverte come un colpo interno, che Vinnicombe è un uomo perso, stordito tra sogni, nessuno sa quello che vorrebbe realizzare, che è tutto nelle sue intenzioni interiori. Allo stesso tempo non può non immedesimarsi in quell’uomo, come facciamo incontrando strambi tipi, perché la stessa donna che lo osserva come se fosse uno stalker, ricorda perfettamente che anche lei un tempo era stata Vinnicombe. Tutti i Vinnicombe sono uguali se si ferma l’istante. Un tempo in cui Olivia pensava che l’amore fosse tutta un’altra cosa. Era giovane. O forse no.

Una cosa che se ti tocca tu vivi per lui. E basta. Non può andare in un altro modo.

Poi, per molti “il cuore non muore, quando sembra che dovrebbe”, come dice benissimo una poesia, si inserisce nel flusso vitale, nella metamorfosi, come un Ulisse, come l’uomo comune, agile, che va avanti. Per i Vinnicombe no.

(Siamo soltanto alle prime quattro pagine). -

William Trevor was a natural short story writer, and it shows in this collection. The narratives never feel forced, and the reader is given the responsibility of ascertaining for herself what truths are revealed. There's an unsettling open-endedness (of varying degree) to each story. The writer at his core, exposes the extraordinary pain of ordinary people. He plays with comparisons and contrasts in ways which, though incisive and deliberate, seem effortless. He seems to have a particular fondness for those who try to win against time, though no mortal ever can. Some people want to escape the past, because they hated it or wasted it; others want to escape the past because they loved it, and bemoan it's disappearance. Hiding in the future is impossibly risky, and the present is somehow never as it seems, without the benefit of distance with which to view it clearly.

Ordinary life experiences serve as allegory for the realities we would do well not to press too hard to understand in full. The first few stories in the collection most clearly demonstrate that lesson: the wisdom of allowing the truth to unravel on its own.

In the third story, At the Caffè Daria,Trevor employs alliteration which he takes no pain to conceal. He frames the emptiness of melancholy with the rhythm of destination, devastation, and desperation. Further, the framework itself is echoed by the detailed description of the Caffè, and the life which the owner has reclaimed from the wreckage. The story's themes point to the circular, and the familiar. There are recurring cycles of ruin and rebuilding. Even betrayal itself seems ever familiar, with only minute features to distinguish one instance from another, like the slight natural differences in a landscape over time.

Clever Mr Trevor, if he were alive today, would probably refuse to elaborate on the meaning of any of his short stories. I imagine his wry grin as he would meet my befuddlement over Taking Mr Ravenswood with intentional silence. I admit I had to look up some of the latter stories to be sure that I was on the same page with everyone else in my interpretations.

Finally, what Trevor does consistently well is to place us uncomfortably close to the action. We are not allowed the distance of observers. We are mere inches from the faces of the characters, close enough to hear their inner dialogues, suffer their anxieties, and shoulder the gut-churning costs of shame, guilt, and treachery. -

Ordinary people

Vulnerabilità, tradimento, confusione, solitudine, malinconia, coraggio, perdita, mistero, meraviglia. Con le sue storie piane, di vite normali, talvolta irrisolte o vaghe, William Trevor ci ricorda che perdita non necessariamente è sinonimo di sconfitta e che a tutto si sopravvive.

10 bellissimi racconti.

https://youtu.be/G5X5IrA0zEs -

Gli attimi fuggenti

Delicatissimi racconti di solitudine suburbana, dove Trevor, al posto della natia Irlanda di precedenti raccolte (Notizie dall’Irlanda), qui ambienta le storie in terra inglese, nella zona londinese soprattutto, ma in fondo ben poco importa perché le atmosfere, i personaggi, i temi restano quelli cari all’autore.

Forse perché predilige in prevalenza adottare il punto di vista di protagoniste femminili, oltre che per la propensione alla forma racconto, Trevor è stato non a torto paragonato ad Alice Munro, ma rispetto alla grandissima canadese, i suoi racconti appaiono privi delle svolte geniali con cui la Munro ama disorientare il lettore, dislocandone e talora capovolgendone le cognizioni acquisite.

Questo elemento non sembra far parte della tavolozza di Trevor che sceglie un percorso pi�� lineare ed uno stile soffuso nei suoi racconti, dove le poche scosse esistenziali subite dai personaggi in genere sono già avvenute, a volte riaffiorando in brevi flashback, oppure hanno appena cominciato a sedimentare i loro effetti, e soprattutto l’autore evita di alterare la perfetta geometria del racconto, che termina sempre in sordina e mai o quasi mai con un colpo di scena.

La malinconia sembra dunque il principale registro utilizzato da Trevor e il fatto di mettere molto spesso al centro della narrazione figure simili (donne di età matura talora prossima all’anzianità) conferisce una patina di uniformità alla raccoltà, tanto che a volte si ha l’impressione di seguire da una storia all’altra una medesima protagonista, in genere solitaria, con le proprie cicatrici del passato, le residue aspettative, soprattutto con il ricordo di momenti (pochi) conservati in fondo all’anima come in uno scrigno, che per un attimo riemergono alla memoria quando è troppo tardi per trarne beneficio.

L ‘accuratezza dei dialoghi, delle descrizioni di modeste abitazioni suburbane, dell’interazione pacata fra i personaggi, senza mai un episodio violento o esplicitamente drammatico, rappresentano la cifra di La ragazza sconosciuta e delle altre storie, che forse non sono tutte riuscite e allo stesso livello. Ma in definitiva mi pare inutile stilare una gerarchia fra i racconti, a maggior ragione all’interno di una raccolta talmente precisa che ognuno di essi sembra occupare il medesimo numero di pagine, ulteriore segnale di quanto sia rigoroso il controllo che Trevor esercita sulla propria scrittura. -

I started to read William Trevor’s books in the late 1990s and consider him as one of my favorite authors. His fiction and short stories are equally good. I joined GoodReads about 2 months ago and wanted to start to build up my library/books read here, since I do enjoy reading.

He started out in public relations! Thank goodness he turned to writing. His first novel won him the Hawthornden Prize of 1964 (The Old Boys).

I have saved a number of his short stories from the New Yorker. From this collection I have "The Women" published in 2013.

I read through many of the reviews of this book and was heartened by those who knew his collection of writing quite well spanning decades (and described his style of writing elegantly) and by those who had read this book as being their introduction to him....and invariably the newcomers said they were going to read more of him. That made me feel good. -

Two or three worthy of any ‘Selected’ volume (‘Mrs Crasthorpe’; ‘The Unknown Girl’ definite inclusions) and none anything but enjoyable additions to a towering legacy.

-

ho letto un paio di volte "Al caffè Daria", uno dei racconti di quest'ultima raccolta dello scrittore William Trevor, perché mi mancava un'interpretazione convincente; quando l'ho trovata, o ho creduto di trovarla, sono rimasto molto soddisfatto e ho fatto una camminata in città, per rifletterci ancora, come faccio sempre quando leggo qualcosa che poi mi colpisce.

il racconto è costruito alla maniera della Munro, cioè le rivelazioni vengono fatte dopo che le situazioni e le persone sono entrate in scena: e così scopriamo che il Caffé Daria frequentato dalla protagonista, una signora di mezz'età di nome Anita, è lo stesso caffè in cui veniva con suo padre. Ora vediamo Anita al tavolo correggere le bozze dei libri per un editore; ci facciamo l'idea sia una persona con una propria serenità, un proprio equilibrio. Viene raccontata la storia del caffè, il cui proprietario è un italiano la cui ex moglie, di nome Daria, è fuggita con un poeta. Stabilitosi a Londra, apre il caffè e lo intitola proprio alla donna che lo ha tradito, come se di questo amore il nome avesse mantenuto il suo cuore incorruttibile. Qui Anita, un giorno, incontra una donna di nome Claire. Claire è una sua vecchia amica, la quale sa dove poterla trovare, nonostante sia passato molto tempo. E' venuta fin lì per comunicarle che Gervaise è morto. Scopriamo che Gervaise è l'ex marito di Anita, ma che si è legato a Claire. Ci immaginiamo un odio furioso, il testo ce lo lascia trapelare visto che tempo fa Anita avrebbe voluto vedere "sfregiato" l'incantevole viso di Claire. Ma la sua reazione è strana: dapprima si mette a vagare, ritornando alla casa in cui ha vissuto con Gervaise e dove quest'ultimo viveva con Claire (ora messa in vendita), poi realizza che l' amicizia con Claire, quella cosa che l'amore ha interrotto, era in effetti la cosa migliore. Ci sarebbero i presupposti per rinsaldare il vecchio legame con l'amica, ma ormai tutto è troppo tardi.

é una storia strana, e per certi versi ambigua, e poi c'è come una doppia chiave malinconica: mi sembra che qui il tempo perduto sia perduto due volte; la prima è il tempo speso da Anita nel riconquistare la sua serenità dopo quel grave tradimento e la nostalgia di quel rapporto sentimentale (questo tempo occupa gran parte della sua vita); la seconda la realizzazione che quel tempo speso nel pensare a quell'uomo ed elaborare quella specie di "lutto", quindi un tempo tutto interiore, aveva forse sbagliato bersaglio perché la vera nostalgia avrebbe dovuto provarla per la sua amica, è lei ad essere stata davvero importante e se ne rende conto solo adesso. La solitudine, sembra dire Trevor, è una specie di groviglio di tempi irrealizzabili, una sorta di giardino di sentieri che si biforcano, che cresce a tal punto che quando realizziamo o sentiamo ancora battere il nostro cuore per una cosa che non pensavamo potesse essere così importante, questa cosa è distante da noi anni luce, la lontananza è già un abisso incolmabile. -

şimdi ben “yağmurdan sonra”yı yeniden okumalıyım çünkü tam anımsamıyorum.

trevor’ın ölümünden sonra kalan öykülerinden derlenen bu kitap epey farklı. sanki trevor ne yapmış etmiş kadınların zihnine nüfuz edip onları anlatmak istemiş gibi.

hemen hemen tüm öyküler kandırmak, kandırılmak, aldatmak, aldatılmak, yalanlar ve hakikatler üstüne. tüm bunların arasında kendini bulmuş, ne istediğini bilen, ayakta duran kadınlar söz konusu genellikle.

“piyano hocasının öğrencisi” istersek neleri görmemeyi seçebileceğimizi yani sınırlarımızı ne kadar genişletebileceğimizi bize bambaşka bir biçimde gösteriyor. hemen ardından gelen “sakat adam” da biraz böyle. inanmak istemek ve inanmakla ilgili.

“meçhul kız” beni en çok etkileyen öykü oldu. öylesine ölüveren bir genç kadının kim olduğunu araştırmak ve bir anlık bir görüntüyle o kadınla bağ kurmak öylesine ince anlatılmış ki bitirip bir kez daha okudum.

“pastoral bir kış” platonik bir aşktan gerçeğine yelken açarken erkeklerin ne beş para etmez olduğunu yine gözümüze çarpıyor. vallahi william bey narsistiğinden çıkarcısına, uslanmaz çapkınından yalancısına gayet tanıdık olduğumuz hemcinslerini nasıl güzel anlatmış. onları çıkarınca öykülerde kalanlar yalnız kadınlar, ayakta kalmaya çalışan kadınlar ama hep güçlü kadınlar.

son öykü “kadınlar”da trevor’ın önceki kitabında çok daha fazla öyküye konu olan kiliseler dahil oluyor. çocuğunu kiliseye evlatlık vermek zorunda kalan bir kadının yıllar sonraki arayışı ve artık genç bir kız olan çocuğun bu hakikatle ne yapacağı söz konusu olan. kabul mu edecek, ret mi?

en başta dediğim gibi william trevor öykülerin hepsinde kendimize ne kadar dürüst olduğumuzu soruyor bize.

püren özgören’in müthiş çevirisiyle. seçtiği kelimelerden bazen öylesine anlıyorum ki onun çevirisi olduğunu. o da yüz kitap da çok yaşasın, var olsun. -

I could not attempt prose in a review of these haunting tales. I knew only that from the outset I realised they were all about shadows. The frown in verse 2 was real enough!

The poem sweeps through all the tales, the quotations in italic an indication of where the story changes. I think the poem does contain spoilers, for which I apologise. A poem reaches its own finale, and I couldn’t have written it otherwise.

Last Shadows

Watch these astonishing shadows slip and lurk;

see the mould on their shoes; you know them,

flagrant they are, in the day’s disregard, shame

On them, on us, though we may shun remark.

The vanguard shade so light, so small, he calls

a balance struck; and yet a frown clamps down

to the scale’s ensuing swing; a man will meet

an end, by certain careful quiet men observed,

men encased in shades, undercurrents in the air,

in a hollow land their certitude in cautious silence

merely nodded into place. Their transient shadows bear

secrets seeded in a strange, and broader, soil.

Now, old story shapes hold sway, echoes relate

each night the searing notes of loss, catastrophe;

the ripening of grapes a tortured and extended plain,

once, twice, thrice betrayed, beyond, always, again.

The haunting grey of spectres swiftly starker,

the minutes of their sojourn coldly darker,

the story of a capture cranks its sordid wheel,

two figures crossed a darkened road, reveal

two who fail; mercy not light, nor even in this dusk

resplendent. All of it a mockery! The widow tries,

must also fail, this drawn coquette, visions vain

beside her where she tramps, shadows worse

than so far we have met, now youth enmeshed,

the human trap the unassailable, the fastness

chinked with no more than a stranger’s sense

of pity, a maelstrom in the refuse of a night.

Ah, if only She, femme sublime, had known the unknown girl;

if she had cared to know. Her shadow calls; she listens,

follows, knows: flowers fade, she wished she did not know,

phantoms merciless, dread insistent, into her garden light,

Slay. Awful duty rears; and we, with stranger steps,

entertain suspicion in a little day, two who feign and combat,

beating back the shade that fashions hard the crown

of much deceit. Courage could have brushed glamour

but did not. Unchaste, complicit, we next encounter wings,

Not ours, but we are shown, against a tawdry stage,

Wingbeats braving, flailing, sailing, as you will, the one

electric light . . . the darkness round intense. The light.

An idyll: or else, Myth claimed this grave, confronts the shades

of life and death, remonstrates with queerness and a lack

of form, solidity; unease must flee before a notion, call it

conscience, fate, necessity; the shades recede, concede

their place before a human will. This end is tinged; their glee

adopts a newer turn, invades where women scavenge, glean,

the press of secrets blotting out the dawn. Our poet names,

with blistering stroke, their whisper of consoling doubt. -

Come tutti i racconti di Trevor: bellissimi.

Vecchio stile, forse. Ambientati nel passato, in un mondo senza smartphone, senza internet, certo.

Ma non è questo che conta.

Contano la sensibilità per i dettagli, le rare parole, la delicatezza dei ritratti, la malinconia struggente, i dilemmi delle persone, l'abisso in cui così facilmente si cade.

Conta l'attimo che Trevor sa cogliere, sempre paragonato a una vita intera. -

I will now embark on reading every single word that William Trevor has ever published.

-

William Trevor seems to be a much adored author in the blogosphere, and he has been on my radar of authors to try for a number of years. Before picking up his posthumously published collection, Last Stories, I had only read a Penguin Mini entitled Matilda's England. I liked this well enough, but it did not push me to pick up any more of Trevor's work, and I wish it had.

Trevor is described on this particular book's blurb as an author 'widely regarded as the greatest writer of short stories in the English language'. This high accolade is matched by John Banville, who calls him 'at his best the equal of Chekhov', and Yiyun Li credits him with her entire writing career.

I chose to begin what will hopefully be an exploration of Trevor's entire oeuvre with his final collection of stories, simply because it was the only volume written by him which my local library had in stock. It is comprised of ten stories, all written towards the end of his life. The blurb of Last Stories declares that Trevor 'illuminates the lives of ordinary people, and plumbs the depths of the human spirit.'

Largely, Trevor's stories focus upon normal, everyday occurrences, which could, in theory, affect us all. In 'At the Caffè Daria', two women who used to play together as children - 'Anita round-faced and trusting, Claire beautiful already' - meet by chance in a London café, and Trevor recollects their complex history. Of single mother Rosanne in the story entitled 'Taking Mr Ravenswood', he writes: 'Sometimes it wasn't bad, being alone, especially when she was tired it wasn't, no effort made, none necessary, and the silence when the television was turned off came like a balm. But the silence could be a vacuum too, and often felt like that.' The protagonist of 'Giotto's Angels' is suffering from amnesia.

There is such a knowing quality to Trevor's writing, and in consequence, one immediately gets a feel for each of his characters. We are made aware of what is important to them, as well as things that have occurred in their lives which have some impact upon their present selves. He displays such complex human emotion, and dignifies every single one of his characters in Last Stories with motives and realistic feelings. In 'The Piano Teacher's Pupil', for instance, Trevor writes: 'All her life, she often thought, was in this room, where her father had cosseted her in infancy, where he had seen her through the storms of adolescence, to which every evening he had brought back for his kitchens another chocolate he had invented for her. It was here that her lover had pressed himself upon her and whispered that she was beautiful, swearing he could not live without her. And now, in this same room, a marvel had occurred.'

Relationships and loneliness are at the core of Last Stories. In 'The Unknown Girl', a young woman is killed in a traffic accident, and one of her previous employers, Harriet, is asked if she can give any details about her, for 'nothing appears to be known about the girl. Little more than her name.' In the same story, Trevor sets out, in a discerning manner, the relationship between Harriet and her son, Stephen: '... this evening, as on other evenings, an undemanding affection one for the other made their relationship more than it might have been. Their closeness came naturally, neither through obligation nor for a reason that was not one of feeling; and it was never said, but only known, that different circumstances, coming naturally also, would change everything. They lived in a time-being, and accepted that.'

Last Stories is an exquisite collection, by a thankfully prolific author. The tales here are thoughtful and perceptive, and I felt pulled into each of them straight away. The stories are all quiet ones, but they and their characters are still rendered highly memorable by the strength of Trevor's prose, and his insight. There is an element of unpredictability here, and some of the stories certainly surprise.

I feel so lucky that I have Trevor's entire oeuvre to read my way through, and imagine that the stories which I find will be just as touching and memorable as those collected in Last Stories. I can see him becoming one of my favourite authors, and cannot recommend this collection enough. -

“The art of the glimpse” was how William Trevor described short-story writing. And in this type of art the Irish writer excelled. His “Last stories” have an added value being his last collection prior to his death in 2016. Like the other, superb, collection, “After rain”, they focus on people, individual lives, like a nano-surgery of the psyche, deriving out of seemingly uneventful lives which are nevertheless fully shaped by one’s past, the one we all carry, whether we know it or not. Men and women watching life go by and vainly trying to catch it, like a hand within a river (to paraphrase M. Proust), co-habiting with regrets, either feeling them cripple their life or at least numbing it, but also always remaining determined to proceed. There is always the memory but also its loss and how despite that loss there are atavistic defenses, survival modes. In short, these stories portray how a seemingly simple life is lived, with all its hills, mountains and plateaus. There is a sadness but not a dead-end. There is disappointment but not total rejection. There is no “is there hope?” dilemma, but acceptance of what is, self-realization and advance.

I discovered William Trevor only now and it is beyond me how this superb artist didn’t amass even more prestigious awards than he already did. If one wants an ex-ray of the soul, a story full of back-stories barely whispered but clearly inferred, a non-linear but not mind-boggling narrative, and last but not least a masterful (understatement) usage of the English language William Trevor is a paragon. Simple as that. -

Reading this was akin to leafing through an old album of family snapshots, many of them faded, mostly strangers now; individuals identifiable only by scribbled notes: “George and Aunt Faye, Easter” “Mr. Johnson and Charlotte at the lodge”. The mood is somber, often dismal. A common theme runs through the stories: dreams unrealized, roads not taken, lives elapsed rather than lived. William Trevor shares with so many other Irish writers (

Brian Moore,

Billy O'Callaghan etc.) a preoccupation with lost souls, failed relationships. Trevor portrays human frailty with penetrating insight, even sympathy.

Conventionally, one might suggest that all of his characters (a love-obsessed stalker and his even more pathetic abandoned wife; a lonely widow seeking out any male company available; a lone, friendless girl struck down by a truck; two aging women at odds with each other about a man lost to both of them) are damaged in some way. But it seems more probable that they’re just the way they’ve always been: ineffectual. There are no great tragedies here other than the mundane tragedy of a marginal existence.

For me, just one of the stories, Giotto’s Angels, stood out from the rest. Even though it was pervaded by melancholy like the others, it was more appealing primarily because its two characters were more fully drawn. But in the end, even the best of his stories comes across as a penny serenade in a minor key. -

3.5/5

William Trevor’la ilk karşılamam yine Yüz Kitap’tan çıkan Yağmurdan Sonra ile olmuştu ve detayları hatırlayamasam da öykülerin genelini sevmiştim. Son Öyküler’i ise biraz daha az sevdim. Bunun temel nedeni de karakterleri güçlü ve ilgi çekici bulmama rağmen öykülerin aynı oranda etkileyici olmaması bence. Başrole kadınları yerleştiren yazar, aldatılmış, terk edilmiş, bir şekilde yalana maruz kalmış, en olmadı kendini kandırabilen, yalnız hatta görünmez karakterler sunuyor bize. Doğrusu her öykü başlangıcında bu defa çok güzel bir şey okuyacağım sanırım diye düşünürken öyküleri bitirince bir yarım kalmışlık hissiyle baş başa kaldım. Sanki öykülerin daha devam etmesi gerekiyormuş, bu halleriyle bir yere varmıyorlarmış gibi hissettim. “Sakat Adam” öyküsü derlemede en beğendiğim öykü oldu. Çünkü sınırları baştan sona belirsizlik üstüne tasarlanmıştı. Bunun dışında “Piyano Hocasının Öğrencisi”, “Bayan Ravenswood’u Kabullenmek” ve “Meçhul Kız” da benim çıkan öne çıkan öykülerdi. Bu derlemeyi çok sevemesem de William Trevor’ın çok iyi bir yazar olduğu kuşkusuz. Gerek kadınları gerek erkekleri ele alma ve hemen her konuya çok boyutlu bakabilme yetisine hayran kaldığımı da söylemek isterim. -

Ten stories in this thirteenth collection of short stories by Irish author who gave us some beautifully built quirky characters out of another unlamented era. They are slightly depressing but I did appreciate them anyway. I did spread it out alternating between other reading material to bring fresh eyes.

Born in County Cork in 1928, Trevor attended Trinity College. -

2 1/2 Stars

This was a set of short stories that presented strong characters but mostly weak plots.

I never really got fired up on any of the stories. Maybe others will -

113th book 2020.

The short story is deep-rooted in the Irish literary tradition. On one level, I think most of the Irish short stories I've read are very similar in tone, or 'formula', and in that respect, they are all very similar to Joyce's

Dubliners. I read an interesting article recently whilst sourcing critical theory on

Finnegans Wake for a University essay that suggested that Joyce had indeed 'made' and ruined Irish literature forever. The old question: what can one possibly write after Joyce? Partly, he is still echoing through Irish literature.

Joyce notwithstanding, Trevor has certainly had a brilliant career in writing and this collection was published two years after his death in 2016, aptly called 'Last Stories'. He wrote twenty-four 'much-lauded' novels, he won the Whitbread Prize three times, and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize four times. According to my edition, "Trevor was widely recognised to be one of the greatest short-story writers in the English Language." In 2002, he was knighted for his services to literature. With all that in mind, these are the final stories of a great writer, after a long and successful career.

And these are beautiful, wonderfully written stories. But, in the way they remind me a little of Joyce, I also have a problem with them.

Dubliners isn't my favourite Joyce work. But I'll stop talking about Joyce and focus on Trevor. His stories are quiet, they leave a lot 'out' (rather, there is a lot left unsaid), and often, not a lot happens in them. I found few of them engaging. The best, as I have seen suggested in several other reviews, is indeed, "An Idyll in Winter". The first in the collection (I think I read somewhere it is the very last thing Trevor wrote) is also very good. A lot of them felt they were lacking substance, emotion, description... something. The short story is a wonderful form and takes many forms. I prefer epiphanies when reading, I like the work of

Raymond Carver,

Ernest Hemingway,

Jorge Luis Borges. I have no doubt these are exceptional stories, and I can think of several people who may love them for their brilliance, but they are not my preference when it comes to short stories. I am glad, however, that I have finally read some William Trevor. -

I came late to knowing Trevor’s work, through the brilliant novel, The Story of Lucy Gault. I have now read enough of his fiction to see how his trademark talents are displayed in this, a posthumous collection of short stories. He takes a situation, a fragment, a character or two and intersects their lives, their pasts, their uncertainties. He chooses for the most part characters who live on the margins of society or who live lives that are not what they would have chosen. His tone is meditative, often melancholy, often evasive. His endings show an acceptance of the essential loneliness of the human condition, an acceptance that absence can sometimes be more palpable than presence, that doubt can be more comforting than certainty.

My favourite story was An Idyll in Winter. Mary Bella was a girl when her father employed Anthony as a tutor in her isolated country home by the moors. The adoration she felt for him then is rekindled when he calls in unexpectedly many years later. The effects on her, Anthony and on the family he decides to leave behind are explored and the ending, as in most of these stories, unexpected but subtly satisfying.

Some of the stories didn't work as well for me; hence not quite four stars.