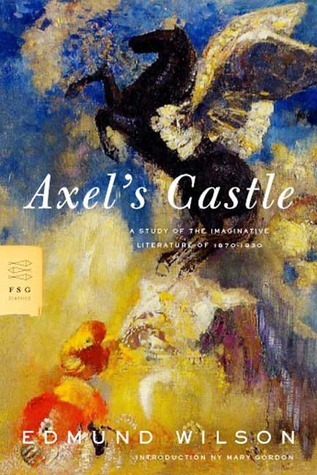

| Title | : | Axel's Castle: A Study of the Imaginative Literature of 1870-1930 (FSG Classics) |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0374529272 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780374529277 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 254 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1931 |

Axel's Castle: A Study of the Imaginative Literature of 1870-1930 (FSG Classics) Reviews

-

I'm in what I hope is the middle of a long period of incuriosity. Books don't really interest me these days, because most of the time when I pick one up, I think, what's the point, anyway? My inner devil likes to whisper that books haven't made a material difference in my own life besides maybe a slight air of well-read-ness, and maybe not even that. Depression isn't like having a raincloud over you all the time, it's more like a hangnail, annoying you whenever you try to do something you normally enjoy, and the harder you try, the harder the nail tries to tear itself from your finger.

So normally this wouldn't be the best time to read a disquisition on Modernism. This prose goes down so easily, though, that I ran out of reasons not to finish the book after having started it last September. Edmund Wilson is unique for me among early 20th century critics in that he sounds almost exactly up-to-date, and I don't think opinions of Valery or Eliot or Proust have really changed all that much since he wrote this critical assessment. Wilson's own writing is exacting without being fussy, and contemporary without being modish.

The exciting thing about this book is seeing Proust and Joyce and Yeats before there was a unified critical opinion as to their value. You get the sense that Wilson knows he's creating the consensus, and by bucking it occasionally he only firms up the broader narrative. As an example, Wilson had the privilege of being able to read "Four Quartets" without the weight of their putative greatness balanced over his head, and instead of praising the book without qualification, he says:

"...I am a little tired of hearing Eliot, only in his early forties, present himself as an 'aged eagle' who asks why he should make the effort to stretch his wings. Yet 'Ash Wednesday,' though less brilliant and intense than Eliot at his very best, is distinguished by most of the qualities which made his other poems remarkable: the exquisite phrasing in which we feel that every word is in its place and that there is not a word too much; the metrical mastery which catches so naturally, yet with so true a modulation, the faltering accents of the supplicant..."

The section on Proust performs more lay psychology than would probably be considered prudent these days, but while Wilson has little respect for Proust, he admires his habits of mind, and wishes only that Marcel had had to "meet the world on equal terms and [...:] felt the necessity of relating his art and ideas to the general problems of human society..." The last lines on Proust are so excellent that I won't reproduce them here - read the book. Anyway, Wilson prefers the fiery revolutionary Yeats, while finding his theories on history and his metaphysics to be rotten caricatures.

It is striking and rare to read someone with such nominal opinions of major early 20th-century writers express them in a voice that's so familiar yet inventive. Wilson seems to have understood with clarity the importance of the Symbolist and Modernist movements even as they coursed, developed and died all around him. Imagine writing at a time when the world had seen only a few serialized chapters of Finnegan's Wake!

Chew on this:

Axel's Castle was written when Texas was still a depopulated backwater mostly without electricity. It was written twenty years before Hawaii or Alaska became states. It was written before American highways existed. It was written when cars were still a novelty in some parts of the country. It was written before anyone knew Wallace Stevens had written much poetry. It was written before Hitler came to power. You'd never guess it from the words on the page. -

Somewhere in the previous Wilson I recently read, the critic states that one of his favorite times in life is when he's able to describe a book to someone unfamiliar with such. That ripple of joy is on display here. Often. I truly wish I had read this book 30 years ago. It was probably the number of poets within which discouraged me at that time. Those childish things. A shrinking violet--in flannel. But a flaneur, nonetheless.

Wilson cites the advent of Symbolism as the movement which brought to the fore Joyce, Proust and Stein. The critic then develops a thesis of Romanticism being a response to Classicism. Naturalism then became a conservative easing of the Romantic fire which then led to the insular quest of Symbolism, crafted in a lab by the wonky Mallarmé and other, lesser, lights of contention. I find it odd that Valéry received a chapter but Huysmans did not. The effect of the Great War also appears nebulous in this reasoning.

There was much to learn in this ostensible primer. There was also a great deal of plot description. Some would wager an excessive amount. We can't deny Bunny his pleasure. My personal ax on Axel: not enough Freud and Faulkner. -

(5-stars was too much; corrected)

Wilson’s essay on the nature and origins of Modernism in literature is lucid, clear, and direct, and is worth familiarizing oneself with. After an initial, very brief discussion of Romanticism – seen as a revolt against the mechanistic rationalism of the 17th and 18th cen., in which the universe (man included) were viewed as a clock-like mechanism (there is a good discussion of all this in J.B. Bury’s, The Idea of Progress), and god as the clock-maker who, once having set it in motion withdraws to watch his handiworks… Wilson describes the initial reaction against Romanticism as the Naturalism of Flaubert and Ibsen (and, in art, Courbet). The reaction against this, was the Symbolism best exemplified by the lunatic Gérard de Nerval, Poe, and ultimately by Mallarmé.

The chief doctrine of Symbolism can be expressed as follows (p. 21f.): “Every feeling or sensation we have, every moment of consciousness, is different from every other; and it is, in consequence, impossible to render our sensations as we actually experience them through the conventional and universal language of ordinary literature…. Each poet… [must] find… the special language which will alone be capable of expressing his [unique] personality and feelings. Such a language must make use of symbols [not conventional symbols, as in the Middle Ages; but unique and eccentric ones]: what is so special, so fleeting and so vague cannot be conveyed by direct statement or by description, but only by a succession of words, of images, which will serve to suggest it to [or invoke it in] the reader…. Symbolism may [therefore] be defined as an attempt by carefully studied means – a complicated association of ideas represented by a medley of metaphors – to communicate unique personal feelings.”

Already in Poe, who strongly influenced French Modernism through the translations of Baudelaire in 1852, we find the aesthetic stated thus “’I know… that indefiniteness is an element of the true music [of poetry]… a suggestive indefiniteness of vague and spiritual effect’. And to approximate [Wilson continues] the indefiniteness of music was to become one of the principal aims of Symbolism. This effect of indefiniteness was produced not merely by the confusion… between the imaginary… and the real [as in Nerval]; but also by means of a further confusion between the perceptions of the different senses.”

Comme de longs échos qui de loin se confondent…

Les parfums, les couleurs et les sons se respondent (Baudelaire)

One of the best expressions of Symbolism turns out to be Paul Valéry, who did not write much, but who dedicated himself (ultimately through his notebooks) to the “study of oneself for its own sake, the comprehension of that attention itself and the desire to trace clearly for oneself the nature of one’s own existence”.

Wilson sees Modernism as the working out of Symbolism either in tandem with, or in reaction to Naturalism. To show how this is so, he dedicates separate chapters to Yeats, Valéry, Eliot, Proust, Joyce, Gertrude Stein, with a final chapter on ‘Axel’ (a poem by Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, publ. 1890) and Rimbaud.

In this final chapter, Wilson begins by tracing the ethic that resulted from this fin de siècle aesthetic. “One’s great objection to the Symbolist school,” says Gide, “is its lack of curiosity about life… all were pessimists, renunciants, resignationists, ‘tired of the sad hospital’ which the earth seemed to them… Poetry had become for them a refuge… Divesting life as they did of everything which they considered mere vain delusion… it was not astonishing that they should have supplied no new ethic – contenting themselves with that of Vigny, which… they dressed up in irony – but only an aesthetic.”

It led, Wilson argues, to the withdrawal of the individual from everything social, into a kind of exquisitely polished internality… of M. Teste, of ‘Marcel’ in A la Recherche… all of which ultimately brings him to to the poetic will-to-power of Rimbaud’s Enfer, a very different course and path…, closing with a lengthy account of Rimbaud’s final years in Africa.

Clearly, Wilson is impressed with Rimbaud and with the arc of his life and his career, concluding: “Rimbaud was far from finding in the East that ideal barbarous state he was seeking; even at Harrar during the days of his prosperity he was always steaming with anxieties and angers – but his career, with tis violence, its moral interest and its tragic completeness, leaves us feeling that we have watched the human spirit, strained to its most resolute sincerity and in possession of its highest faculties, breaking itself in the effort to escape, first from humiliating compromise, and then from chaos equally humiliating. And when we turn back to consider even the masterpieces of that literature which Rimbaud had helped to found [subsequent poetry] and which he had repudiated, we are oppressed by a sullenness, a lethargy, a sense of energies ingrown and sometimes festering. Even the poetry of the noble Yeats, still repining through middle age over the emotional miscarriages of youth, is dully weighted, for all its purity and candor, by a leaden acquiescence in defeat”. (283) -

The Qabalistic Palimpsest of Axel’s Castle

Sylvia Plath’s boyfriend, Gordon Lameyer, gave Plath the book Axel’s Castle: A Study in the Imaginative Literature of 1870-1930, by Edmund Wilson, to read while recovering at McLean after her attempted suicide in 1953. My fellow scholars have teased me about my “crush” on Gordon. He was gorgeous, smart, into literature, and completely devoted to Plath. But this post is not about him, it’s about the book.

I had been interested in Axel’s Castle for a long time, and bought a copy long ago which I finally got around to reading this week. Knowing that Joyce and Yeats were into Kabbalah/Cabala/Qabalah, and knowing that Lameyer seemed to be quite open to ideas of mysticism, as well as his being a major Joyce scholar, I knew there must be something here of interest here. In a letter, Plath thanked Lameyer for it and said it “will take me to new depths in my dearly beloved Yeats, Joyce and Eliot…” (LSP, 652)

Author Edmund Wilson is dry—even Plath thought so, although in her letters she said that she mostly got it (LSP, 660). Axel’s Castle traces the origins of contemporary literature and the development of the imaginative style among six writers of a common school: Yeats, Joyce, Eliot, Proust, Gertrude Stein, and Paul Valéry. Here, I’ll review the chapters that I know interested Plath: Yeats, Eliot, and Joyce, as well as the introduction and conclusion.

In Chapter One, Symbolism, Wilson discusses how this school of literature begins with Romanticism, where the writer becomes a part of the story. What we call “meta” today, although it was in the voice for its time. Romantics see “the world is an organism, that nature includes planets, mountains, vegetation and people alike, that what we are and what we see, what we hear, what we feel and what we smell, are inextricably related, that all are involved in the same great entity” (AC, 5). Yes. Wilson didn’t realize he did a fine job describing Qabalah.

[The Romantic Poet] “is the prophet of a new insight into nature: he is describing things as they really are; and a revolution in the imagery of poetry is in reality a revolution in metaphysics” (AC, 5-6). Well, well! Maybe Wilson does realize this is Qabalah?

It’s funny. For me, having read so much Qabalah to understand Plath, I missed the point that it can be a loose relation of things. As an author with a new approach to Plath, I have worked so hard trying to prove that this means such-and-such, when I should have just read more of what Plath read. Live and learn, right? In reality, Qabalah is an association game. Wilson explained:

“To name an object is to do away with three-quarters of the enjoyment of the poem which is derived from the satisfaction of guessing little by little: to suggest it, to evoke it—that is what charms the imagination” (AC, 20). Yes, it’s time to loosen up a bit in my next books.

Poets invent a special language, Wilson wrote. “Such a language must make use of symbols […] a succession of words, of images, which will serve to suggest to the reader” (AC, 21). He continued that the Symbolist movement is “principally limited to poetry of a rather esoteric kind” (22). This has been my point exactly, stressing that Plath is more Symbolist than anyone gives her credit to be.

Chapter Two of Axel’s Castle focuses on Yeats, who believed that the Symbolists were the only ones doing anything new in poetry (AC, 26). Plath had been schooled thoroughly in both Yeats and Joyce, and knew all about their mysticism. She had read A Skeleton’s Key to Finnegans Wake to learn about Joyce’s Kabalistic (he spelled it with a K) endeavors, and she would soon read The Unicorn: William Butler Yeats’ Search for Reality, which is a deep discussion on his alchemy and occult activities as it shaped his work. A review of the former has already been posted, and one of the latter is forthcoming.

Axel’s Castle details Yeats’ Rosa Alchemica, called by critics to be his best work of fiction, exploring Yeats’ passions for myth, legend, Irish culture, and his lifelong membership of over thirty years in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn secret society as a practitioner of magic and alchemy. There are too many details to include here, but the subjects are: Rosicrucianism and alchemy (AC, 32-34); the Tree of Life (AC, 43); the Phoenix (AC, 44); his 1922 autobiography of occultism, The Trembling of the Veil; astrology; clairvoyants; magic; Madame Blavatsky; Theosophy; Yeats’ 1901 essay on Magic and its principles (AC, 47-48); Myths, trances, dreams and visions; mediums; and even Yeats’ interest in psychoanalysis and anthropology (AC, 48). All of these topics were of great interest to Plath and her husband, Ted Hughes.

Author Edmund Wilson quotes Yeats about quarreling with AE Waite, a creator of the modern tarot and Rosicrucian leader, about magic and rationality (AC, 48-49). In Yeats’ mind, and later on in Plath’s too, there was room for both.

Wilson wrote that Yeats had a firm grasp of Freud and Jung’s psychology and symbolism, as well as William Blake’s elaborate “mystical-metaphysical system” to explain psychology (AC, 49). We know Plath knew all of these writers/thinkers inside-out, so Yeats’ system would have made perfect sense to her.

Next discussed is Yeats’ A Vision (1926), a book encompassing human personality, history, and the transformations of the soul—aspects Plath would incorporate in her own work, with the instruction of Yeats’ diagrams, orbits of the moon, philosophies and defined concepts such as daimons, tinctures, cones, gyres, husks and passionate bodies. Wilson says, “Yeats asserts the human personality follows the pattern of a ‘Great Wheel’” (AC, 49). Many consider this wheel to be equivalent to the Tree of Life.

The author made this comment about Yeats which I related to so well when writing about Plath, trying for years to explain this Qabalistic system within Plath’s work:

“and indeed one would think that to elaborate a mystical system so complicated and so tedious, it would be necessary to believe in it pretty strongly.”

And yet Yeats, like Plath, did not consider himself a believer. He reverted to calling his occult endeavors merely “a background for my thought, a painted scene” (AC, 54). The author goes on to challenge that Yeats’ extreme mystical detail is no mere “background,” and I suggest the same for Sylvia Plath. These book reviews are just a small part of my proof that she learned from the masters.

The chapter on Yeats discusses his wife, Georgie, as a spiritual medium, and their practice of automatic writing (AC, 55). Much like in Plath’s long poem, “Dialogue Over a Ouija Board,” there are great details of spirit sessions, sights, smells, sounds and spirit personalities. Also explored is Yeats’ study of philosophy, the prophetic books of William Blake, Swedenborg (religious mystic) and Boehme (alchemist). Yeats is quoted as saying Hermetic Initiation “had filled my head with Cabalistic imagery” (AC, 57). Yeats studied philosophy to understand the “system.” Apparently, during Yeats’ writing of the book A Vision, there was spiritual intervention when he made attempts at revision. Whether or not you believe it, it’s all fun and fascinating. It goes on with lots more about Yeats’ supernatural experiences, his Irish Catholic mysticism, and his very Plathian way of handling faith: “his realistic sense is too strong, his intellectual integrity too high, to leave it out of the picture […] He believes, but ---he does not believe.”

Chapter IV discusses T.S. Eliot, and most especially The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock (1915) and The Waste Land (1922), a long poem as a metaphor for the myth of the Holy Grail, with pagan and Puritan themes. Wilson notes that in The Waste Land, and like we see in James Joyce’s work (and what Plath has done consistently, although no one gives her credit), Eliot “manages to include quotations from, allusions to, or imitations of, at least thirty-five different writers (some of them, such as Shakespeare and Dante, laid under contribution several times)---as well as popular songs” (AC, 110). The author observes that to credit the original sources of inspiration makes some perceive Eliot as “second-hand.” And maybe that is why Sylvia Plath scholars refuse to see the influences I have found in her work. Who can know? Wilson closes the Eliot chapter talking about the difficulty of “where the novelist or poet stops and the scientist or metaphysician begins” (AC, 119).

Chapter VI covers James Joyce, and recaps how Joyce’s Ulysses is a modern Odyssey. He summarizes the story, and which of Joyce’s characters stand in for the Greek gods and goddesses. Joyce’s Ulysses is Bloom, a Dublin Jew, further reinforcing the Qabalah (or, in this case, Kabbalah) within Joyce’s Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, and in Plath’s work. Wilson walks the reader through Ulysses discussing some of the symbolism, showing how Joyce did it differently—neglecting action, narrative and drama for psychological portraiture--in comparison to other writers.

“The first critics of Ulysses mistook the novel for a ‘slice of life’ and objected that it was too fluid or too chaotic,” Wilson wrote. “They did not recognize a plot because they could not recognize a progression; and the title told them nothing. They could not even discover a pattern” (AC, 211).

And so it is with Plath’s work, who made a model out of James Joyce and Yeats (See my Decoding Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy”: Discover the Layers of Meaning Beyond the Brute; and Decoding Sylvia Plath’s “Lady Lazarus”: Freedom’s Feminine Fire (2017, Magi Press).

Wilson draws parallels between Joyce and Yeats, and notes that Yeats was a great influence on Joyce (AC, 221). Wilson, perhaps not knowing Qabalah himself, describes Joyce’s Qabalistic structure perfectly:

“Joyce’s world is always changing as it is perceived by different observers and by them at different times. It is an organism made up of ‘events,’ which may be taken as infinitely inclusive or infinitely small and each of which involves all the others; and each of these events is unique […] everything is reduced to terms of ‘events’ like those of modern physics and philosophy – events which make up a ‘continuum,’ but which may be taken as infinitely small” (AC, 221-222).

There’s so much more I’d love to quote. I imagine Plath studying Joyce and all of his parallel symbols working toward one greater message. Through Joyce and Yeats (and Eliot too), Plath could fully understand Qabalah in words and pictures. Plath had mentors in these authors and their examples to emulate. Yet, she chose Yeats’ medium of poetry as the realm in which to master her spiritual arts. (Writing this, I admit that I do have notes all over a copy of The Bell Jar, identifying a Qabalistic order within that book too. I just haven’t found any layers there. Of course, I’ve barely given The Bell Jar time, as her poetry has taken me over ten years and I am not finished yet).

At the time of Wilson’ writing of Axel’s Castle, Joyce was still at work on Finnegans Wake, which Wilson referred to as “Transition” (Joyce’s working title). The time and description of Transition well describes Finnegans Wake, for us to know it is the same.

“A single one of Joyce’s sentences, therefore, will combine two or three different meanings, two or three different sets of symbols; a single word may contain two or three,” Wilson said, adding, “The style he has invented for his purpose works on the principle of a palimpsest: one meaning, one set of images, is written over another” (AC, 235). He writes that Joyce systematically embroiders his text with all human possibilities (AC, 235-6).

Chapter VIII is the conclusion: Axel and Rimbaud. And throughout the book, I kept wondering, “Who is Axel?” Finally, we have an answer. Axel is the Count Axel of Auersburg, who studies hermetic philosophy of the alchemists, and is prepared by a Rosicrucian for the revelation of the spiritual mysteries. In his castle is hidden the lost treasures of Napoleon. This is all based on the long prose poem, “Axel,” by Villiers de I’Isle-Adams (1890).

Wilson declares that there is only one of two ways to go: Axel or Rimbaud. Rimbaud is a Naturalist and only of the world, according to Wilson. The aforementioned others in Axel’s Castle, the Symbolists, incorporate everything of the world into their literary worlds. Rimbaud has no God, but the Axel’s authors create representations of God with their brilliance. “Men will no longer separate the idea of God from that of human genius, human productivity in all its forms” (292).

Axel’s Castle is a great study of great literature. But even cooler than that, it’s a Qabalah handbook and Wilson didn't even know it. -

Essays on Yeats, Valery, Eliot, Proust, Joyce, Stein, Rimbaud and Auguste de Villiers de l'Isle-Adam (author of the 1890 drama ‘Axël’).

Before its publication in “Axel’s Castle” a fair amount of this material was evidently published in the New Republic where Wilson wrote until 1931, the year “Axel’s Castle” was released. In that year Wilson was 36, only 7 years younger than Eliot, for whose ‘The Waste Land’ Wilson was the first American reviewer. Wilson is also said to be one of the first to review Joyce’s ‘Ulysses.’ Joyce was 13 years his elder.

The essays here are often pleasurably lucid, though at times perhaps a bit too deferential, and best when hewing closest to biography and text, as opposed to the grander literary-historical theorizing prominent in the concluding chapter. However, as indicated by the hint of a cohort registry above, it’s difficult, now some 80 years on, not to view “Axel’s Castle” itself as literary-historical artifact, and grist for a similar sort of rumination.

Oddly, for me perhaps most enjoyable was watching Wilson attempt to come to terms with Gertrude Stein, generously including (as he also does elsewhere) large chunks of illustrative text, as in:

“One was quite certain for a long part of his being one being living he had been trying to be certain that he was wrong in doing what he was doing and then when he could not come to be certain that he had been wrong in doing what he had been doing, when he had completely convinced himself that he would not come to be certain that he had been wrong in doing what he had been doing he was really certain then that he was a great one and he certainly was a great one. Certainly every one could be certain of this thing that this one is a great one.”

(And this is Stein at her relatively more coherent. Consider this, from “Tender Buttons” of 1914:

“A PIANO.

If the speed is open, if the color is careless, if the selection of a strong scent is not awkward, if the button holder is held by all the waving color and there is no color, not any color. If there is no dirt in a pin and there can be none scarcely, if there is not then the place is the same as up standing.”)

I found it somehow extraordinarily sweet to see a sensible man (as Wilson presents himself) struggle to rationalize Stein’s remarkably inappropriate abstract prose, excerpting lengthy passages from Shaw and the United States Courts-Martial Manual as counter samples of language use, and being led off into the dark alleyways of the meaning of meaning. This, I confess, was a most amusing deferentiality.

In the closing paragraph of the final chapter (that of the grander literary-historical theory) Wilson almost off-handedly refers to the possible death of “the whole belle-lettristic tradition of the Renaissance.” One thinks, depending on how one takes it, that he’s likely speaking of the venue of his own ambition. But in another sense the opposite may be true, and that in “Axel’s Castle” Wilson was not only witnessing, but also, for better or for worse, fostering and amplifying a new 20th century belle-lettristic renaissance.

-

It is so refreshing to read literary criticism where the writing is concise and to the point. Edmund Wilson has done a masterful job on the essays on symbolism, Marcel Proust, James Joyce and Gertrude Stein. The summary portion of Proust’s A la Recherche du Temps Perdu is the best I have read. I am not as familiar with the some of the authors covered in this book, so I will reserve comment.

Nothing is more disheartening than to read a great piece of literature, delve into some of the criticism and find that the novel in question was much easier to understand than the criticism. You should not need a copy of Cliff’s Notes to weed through literary criticism. Personally, I believe that an overblown academic approach is responsible for this. More than one literary criticism, see Eugen Weber’s work on France: Fin de Siècle, has suffered from this overblown technique of proving your educational worth by talking down to the reader. I realize that I myself was guilty of this technique when I was writing critical papers in graduate school. I wish I could go back and do it over again. It isn’t necessary if your goal is really trying to be understood.

Another issue I have with some contemporary criticism goes like this: “What the author said was….. What he really meant was…….” It is possible isn’t it that the writer meant exactly what he originally said.

I can’t help but feel that the “times” are somewhat responsible for this. Axel’s Castle was written in 1931. Perhaps in those days some were not as compelled to demonstrate their “expertise” in the same ways as today. My hat is off to Edmund Wilson for the effort and result that went into this work. -

It's fascinating on so many levels. I first read it in the late seventies, as part of my "alien minds" project--to try to see through the eyes of minds utterly unlike mine, but with one sharing point (after I made an attempt with the Marquis de Sade, and was just repulsed, but I do not like horror). In this case, the touch point--I thought--was fantasy.

The full title includes the phrase "Imaginative Literature" but Wilson's six writers are not who I would have chosen to represent fantasy. I was actually glad--I wanted to learn what it was he saw worthwhile in Stein, for instance. I loved reports of what she said in the salons of Paris, but her writing was (and still is, to my eye) turgid and impenetrable.

I never bought the Symbolist movement--it seemed more self-consciously "Here I am so great" and pompously "art for the sake of art" than all the elite the expats scorned. Yet they were trying experiments, which I wanted to understand, even if I couldn't appreciate the effect.

Yeats I did come to value in later years; what Wilson gave me was a key to understanding, and appreciating, James Joyce. -

A lot of the connections that Wilson draws seem somewhat obvious now, but I have to think that this was truly revolutionary criticism at the time it was written. The tie between the narrative of the author's life and their conceptions, as well as between symbolism and everything that followed is now Lit 101, but it's still interesting to revisit this idea in its earliest incubation, especially with as charming a guide as Edmund Wilson. It doesn't compare to To the Finland Station, but it's still worth your while.

-

Reputation – 3/5

Edmund Wilson’s 1931 study of Symbolism in Modernist literature is no longer widely read as a book. The essays are more often approached individually, but the analyses Wilson presents have become canonical. It’s hard to find a Joyce or Eliot scholar who does not make a living repeating Wilson’s conclusions to undergraduate students. Thankfully for the livelihoods of those professors, it’s harder to find where these opinions were first expressed. Most of them are in this book.

Point – 4/5

Because these essays are so often read out of the context of the book itself, it is best just to present a short summary of Wilson’s remarks about each writer in sections.

Symbolism

Symbolism is “a second flood of the same tide” of Romanticism. Symbolism first grew up among the French poets who read English poets and introduced new metrics into previously strict forms of French poetry. The prime example of this is Baudelaire’s reading of Edgar Allen Poe. Baudelaire’s early experiments inspired a young generation of French poets who followed his lead: Mallarmé, Maeterlinck, and Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. French writers reading English.

Later English writers like W.B. Yeats and T.S. Eliot read this “new” French and brought its fruit back to English.

This book can be read as criticism about literary cross-pollination: English writers who read more French than English, and French writers who read more English than French. And Wilson proves here that cross-pollination, in literature as in botany, produces richer fruit.

W.B. Yeats

Yeats has achieved a true “style” in both his poetry and prose that calls to mind the stately, individualistic writing of men of letters of the seventeenth century, whose style, in Wilson’s words:

“was a much more personal thing: it fitted the author like a suit of clothes and molded itself to the natural contours of his temperament and mind; one is always aware that there is a man inside.”

This “suit” of Yeats makes him stand out in a generation of writers who wear the ready-made clothes of modern industry, but it also makes him susceptible to obsolete approaches to modern life. In the end, for all Yeats’ allure as a poet and mystic, his rejection of modern life and his seeking refuge in the realm of fairytales and prophecy make us too skeptical of him to take him at his word.

Paul Valéry

Valéry obsesses himself too slothfully with the workings of the mind, rather than with its fruits. He is one of the French first writers to face the math and science of the modern world head on, but he becomes paralyzed by it. He mostly stops writing poetry, convinced he can’t do anything perfect, and focuses on a prose that is superficially philosophical and profound, but is really just stringent and highbrow. Wilson:

”Paul Valéry disregards altogether the taste and intelligence of the ordinary reader: instead of allowing his reader the easy victory, he takes pride in outstripping him completely. And he is read chiefly by other writers or people with a special interest in literature: his poems are always out of print and his other writings are always being published in editions so expensive and limited as practically never to circulate at all.”

T.S. Eliot

Wilson’s essay on Eliot is well-known, especially his pronouncement that

“Eliot, in ten years’ time, has left upon English poetry a mark more unmistakable than that of any other poet writing in English.”

Eliot’s successes are that he has “brought a new personal rhythm into the language,” and that, as a critic, he enjoys “a position of distinction and influence equal in importance to his position as a poet.”

Eliot’s shortcomings: 1) his convictions seem insincere and 2) he has established a sort of “thin lipped” school of literary criticism. Wilson:

1)”We feel in contemporary writers like Eliot a desire to be to believe in religious revelation, a belief that it would be a good thing to believe, rather than a genuine belief.”

2)”One is supposed to have read everything and enjoyed everything and to understand exactly the reasons for one’s enjoyment, but not to enjoy anything excessively nor to raise an issue of one kind of thing against another.”

Marcel Proust

Proust uses the Wagnerian, symphonic structure of “themes,” rather than classical literary devices to achieve a remarkable unity in what is considered the longest novel ever written. Proust was addicted to English literature – especially Dickens and Ruskin – and has introduced into French a type of characterization and moralism that was unknown before him.

In a gigantic book of complicated relations, Proust has managed to sum up the bourgeoisie decadence of fin de siècle France and European civilization as a whole. Wilson:

”Proust is perhaps the last great historian of the loves, the society, the intelligence, the diplomacy, the literature and the art of the Heartbreak House of capitalist culture.”

But he was also an indolent hypochondriac, “a perfect case for psychoanalysis,” who, in the end, drags us into a dream world and makes us rather fall into a coma than face the onrush of modern life.

James Joyce

Certainly the most popular essay from Axel’s Castle, Wilson’s review of Joyce has become canonical.

Joyce has fully assimilated Flaubert’s naturalist innovations and paired them with the tide of Symbolism to create something utterly unique in English. There is no shortage of superlatives for Joyce from those who have understood him, so I will only include one sentence of praise from Wilson:

”Joyce is indeed really the great poet of a new phase of human consciousness.”

Wilson’s judgements of Joyce’s shortcomings are more insightful and interesting:

”I doubt,” Wilson says, whether any human memory is capable, on a first reading, of meeting the demands of Ulysses… that Ulysses suffers from an excess of design rather than from a lack of it,”

and that

“Joyce has here half-buried his story under the virtuosity of his technical devices. It is almost as if he had elaborated it so much and worked over it so long that he had forgotten, in the amusement of writing parodies, the drama which he had originally intended to stage;”

Finnegans Wake, which had been only partially published serially by the time Axel’s Castle was written in 1931, is pinned down with such exactitude by Wilson that is is almost unbelievable he wrote this criticism long before Finnegans Wake was even published. Wilson:

"The best way to understand Joyce’s method [in Finnegans Wake] is to note what goes on in one’s own mind when one is just dropping off to sleep."

Many Joyceans will tell you that this is The Way to read The Wake.

But in the end:

“We can grasp a certain number of such suggestions simultaneously, but Joyce, with his characteristic disregard for the reader, apparently works over and over his pages, packing in allusions and puns… And as soon as we are aware of Joyce himself systematically embroidering on his text, deliberately inventing puzzles, the illusion of the dream is lost.”

Embroidery – perfect single word description of the later decadent Joyce.

Gertrude Stein

No one really reads Gertrude Stein anymore, but she was a force in Wilson’s day, so he makes a few remarks about her writing. She is the female American representation of the surrealist vanguard and is the most forward-looking of all the writers addressed in this book.

”But most of what Miss Stein publishes nowadays must apparently remain absolutely unintelligible even to a sympathetic reader.”

Yet

"Whenever we pick up her writings, however unintelligible we may find them, we are aware of a literary personality of unmistakable originality and distinction."

Axel and Rimbaud

To read the final chapter of this book is to realize how much those pickers who go through this book only reading one or two essays are missing out. Wilson compares the arch Symbolist work, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s Axel, to the life of the man who, with Baudelaire, is most responsible for Symbolism’s genesis – Arthur Rimbaud. One represents the resignation of life in favor of art, the other resigned his art in search for more life.

Those familiar with Rimbaud’s life, with its Parisian perversions, its scholarly solitudes, its anonymous adventures in Abyssinia, will find it retold here with an eminent rapidity and force of style. Wilson is really at his best in this last chapter. In it, you even see the seeds of his next book, To the Finland Station, and that book’s concern for the battle between the life of letters and the life of action.

Recommendation – 3/5

I recommend Edmund Wilson to anyone who likes reading literary criticism. I consider him the North Star of 20th Century American literary criticism. So many of his judgements have turned out to be the standard, and it is always worth seeing them in their first form. In this book, five of the six authors treated were still active when Wilson was writing. Remarkable.

Even if you have no particular interest in Symbolism or these writers, this book is still worth reading because the authors here are THE canonical Modernists. They are worth understanding, if only to not be left out at dinner parties. If you do have any special interest in one of these authors, don’t just read the one essay. Read the whole book. You won’t regret it.

Personal – 5/5

I really love Edmund Wilson. He’s one of the few critics I always return to for pleasure reading. I won’t add any more praise, as this review is already too long. But this reading of Wilson’s treatment of Symbolism brought to mind an idea for a personal criticism:

I’ve been a fan of Bob Dylan since I was very young. As much as I've boundlessly loved his music, I’ve always been a little repelled by his “Rimbaud” phase in which his lyrics are less concrete and more suggestive. Despite liking songs like “Desolation Row” and “Stuck Inside of Mobile…” the ethereal lyrics left me with nothing to hold on to. They were hard to memorize by comparison and sometimes seemed more like slipshod nonsense than anything a great songwriter ought to come up with.

Reading Axel’s Castle gave me insight into another side of Bob Dylan. Along with all his roots in American folk and blues, it became clear that Dylan also drank deeply at the fount of French Symbolist poetry. It made an indelible mark on his style, and was no mere passing phase. Bob Dylan, in a uniquely popular American way, carried on the Symbolist tradition Wilson outlines in Axel’s Castle.

It's great when a book can bring you a resolution long considered question. Even better when it’s so unexpected. -

Wilson approaches everything he studies with the obsessiveness of a historian. It is not enough to understand the meaning of a text or to debate the author’s ideas— instead he looks to the largest scale of events and societies for an explanation of their thinking. He observes, with a telescope as well as a microscope, whatever subject he sets himself upon. This is a timeless book, perhaps because no one has been able to replicate the greatest features of his work— no one has taken his influence and developed farther. In his own oeuvre he has yet to be surpassed, and so he stands as the head of his own branch of criticism and history, still waiting to be supplanted.

-

An excellent, if dated, introduction to many of the century's greatest writers, including G. Stein, Joyce and Proust.

-

I am, virtually without qualification, a huge fan of Edmund Wilson’s essays, if less so of his fiction. While perhaps not at the level of a Macaulay, a Montaigne, a Johnson, a Benjamin, an Emerson, or even an H. L. Mencken, Wilson has written both eloquently and persuasively on a variety of topics. The Triple Thinkers and To the Finland Station come immediately and memorably to mind, even though I read both some thirty years ago.

I can’t express anything like the same kudos for Axel’s Castle. Wilson covers the gamut of interesting personalities and writers (Yeats; Valéry; Eliot; Proust; Joyce; Stein; and Rimbaud – not to mention the Symbolist Movement in general) – but either I lack the necessary enthusiasm for this Movement and these writers or Wilson has simply failed to convince me they’re worth reading.

God knows, Proust and Joyce both have their share of devotees. I’m just not among them. I’ve never read Proust. Joyce certainly proved his writer’s credentials with both Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Dubliners.v But I struggled to complete seventy pages of Ulysses before giving up in utter frustration. I’ve never even attempted Finnegans Wake.

And yes, I’ve read much of the poetry of Yeats and T. S. Eliot and found some of it inspiring. But would I feel the same degree of enthusiasm either for Gertrude Stein or for Paul Valéry? I doubt it. Rimbaud, of course, is in a category unto himself.

For the student of the Symbolist Movement, I suspect Axel’s Castle is a worthwhile undertaking. For the dilettante — which I admittedly am — I would suggest it’s not.

RRB

04/17/11

Brooklyn, NY, USA -

Excellent and enlightening. I learned quite a bit, since this literary period was never my focus in school. Though I think what interested me most was Wilson's ability and willingness to expound on the best and worst of each author. Thus Wilson finds Gertrude Stein to be "a literary personality of unmistakable originality and distinction" who possesses a "masterly grasp of...human personalities," but at the same time he finds much of her writing "boring," repetitive, or "unintelligible," so that "the reader is all too soon in a state, not to follow the slow becoming of life, but simply to fall asleep." He similarly praises the creative genius of Joyce and the intricate layers of Ulysses but points out there are too many; Joyce "elaborated Ulysses too much" and ultimately "a hundred and sixty-one more or less deliberately tedious pages are too heavy a dead weight for even the brilliant flights" of the rest. He has great praise for Proust as a writer despite his penning "one of the gloomiest books ever written," and as a person finds him both an intelligent, dignified "personality of singular magnanimity, integrity, and strength" and a mother-obsessed, passive-aggressive hypochondriac prone to "his self-coddling, his chronic complaining, his perversity, his overcultivated sensibility." It is a fascinating and strangely balanced study of the Symbolist movement and this time period in general.

-

A very important critical commentary on the modernist movement written just after the height of modernist dominance in 1931, this is a book that will help you not to say a bunch of dumb things about the writers discussed. It also posits a pretty interesting point about the tendency of most of the moderns to retreat into their private worlds of art so as not to need to deal with the world of politics and the like, and is sort of an implicit condemnation of art that doesn't help common people to live better. One wonders what Mr. Wilson thought about the continuing story of Mr. Pound in the twenty or so years after he encouraged poets to get out of their castles and into the world.

This book has great things to say about Yeats, Eliot, Joyce and others: it might finally get me to read Proust, for instance, though I've already resigned myself to never being able to pronounce his name in literate society. I also need to report that even the sympathetic criticism of a careful enthusiast like Wilson makes me even less likely to try to read Gertrude Stein seriously. What's that, Dr. Williams? Something about "the rout of the vocables in the writings of Gertrude Stein -- but you cannot be an artist by mere ineptitude"? Unkind, Dr. Williams. -

Oh well, this kind of stuff is way too smart for a country boy like myself. I got something from the chapters on Eliot and Joyce, very little from the chapter on Yeats, and the whole argument about the importance of Symbolism as a unifying influence on the whole gang sailed right over my head. Even Mary Gordon's enthusiastic introduction didn't help.

Giltinan reaches the limitations of his frazzled intellect and beats his wings in frustration, pawing at the ground and snorting.

(yes, I'm Pegasus, what did you think?) -

Axel's Castle: A Study in the Imaginative Literature of 1870-1930 is a 1931 book of literary criticism by Edmund Wilson on the Symbolist movement in literature. It includes a brief overview of the movement's origins and chapters on W. B. Yeats, Paul Valéry, T. S. Eliot, Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein. The book's title refers to Axël, a prose poem by Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam which is discussed along with the works of Arthur Rimbaud in the concluding chapter. Axel's Castle, truly should be considered one of the formative critical texts of American literary criticism.

-

An analysis of the literary trends in English and French literature from the late 19th century through the first three decades of the 20th, as exemplified by the careers of six well-known literary figures: W. B. Yeats, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, Gertrude Stein, Marcel Proust, and Paul Valéry.

For each of them Wilson mixed biographic details with literary analysis. Both types of material were entertaining. The former because they led interesting lives and most of them were rather unique characters. The latter type of material was laden with literary references and abstract sociological/philosophical concepts, but I found that investing the time for a little collateral research on Wikipedia, and carefully reading for a thorough understanding of Wilson’s comments, resulted in an enjoyment which more than justified that investment.

The last chapter – AXEL AND RIMBAUD – finally explained the title of this book. Count Axel of Auersburg is the protagonist of a long poem in prose titled “Axel” (1890) by Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, of which Wilson provides a detailed summary and then uses Count Axel as a symbol of escape from society by locking oneself in a castle. Rimbaud is of course the young French poet Arthur Rimbaud, who retired from poetry at the age of 20 and spent the rest of his life in the less developed parts of the world. For Wilson he symbolizes an escape from the demands of 20th-century Europe through a return to a more primitive society. Axel and Rimbaud were then used to represent alternative means of escape in the future of Symbolist literature. I found Wilson’s biographical summary of Rimbaud’s life the most fascinating material in this book.

I had read works by only three of the six writers featured and therefore found Wilson’s discussion of them more rewarding than of the other three. This was especially true for James Joyce, as Wilson’s recap and analysis of Ulysses, brought to mind certain passages with greater clarity than when I read it nearly six years ago. However, even with the authors and works I had not previously read, Wilson provided sufficient detail to maintain my interest and comprehension. -

Wilson, Edmund. Axel’s Castle: A Study in the Imaginative Literature of 1870-1930. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1931.

Anyone interested in the modernist movement in literature should read Edmund Wilson’s Axel’s Castle. It is much less dated than any work of literary criticism that is almost 90 years old has any right to be. Wilson writes with an almost journalistic clarity about subjects that are themselves sometimes intentionally vague, abstruse, and arcane, and he does so at a time when many of the works he discusses were just beginning to be read and understood in any depth. He writes about James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, for example, when it was still being published in draft pieces. If the romantic poets were reacting against classicism and connecting their own subjective experience to our objective understanding of nature, the late 19th-century French symbolist poets, Wilson tells us, reacted against the objectivity of romanticism and against realism and naturalism. Wilson then locates Yeats in this new symbolist tradition and shows how later in his career he blends it with more realistic elements, as did the early work of Joyce and T. S. Eliot. In discussing Joyce and Proust, he points out that consciousness for them had a much more evanescent quality than it did for the romantics. They needed to catch it on the fly and connect it, not to nature, but to the depths of their own unconscious minds. Language for many of these writers was more important for its suggestive, often private, values than for its denotative connections. This explains, Wilson says, why so many of these works are difficult to decipher. Axel’s Castle is Wilson’s ultimate symbol for language that has become completely self-absorbed and private. He somewhat unfairly, I think, disparages the poetry of Gertrude Stein for this tendency. On a less serious note, Wilson gives me good reason not to read Proust, and suggests that maybe I ought to try to really read all the layers I can in in the palimpsest that is Finnegans Wake. Wilson gets five stars for this one. -

Edmund Wilson is one of the towering literary critics of his time. His erudition and insight are incomparable. The authors and works discussed in this book are daunting by any standards.

Mr. Wilson presents intelligent, intelligible, thoughtful, and elegant analysis. This is literary criticism writ large. -

A landmark in 20th C literary criticism, it holds up quite well. Wilson’s interpretations of Joyce, Proust, and others in real time hold up quite well 90 years on, and plenty of successors have failed to identify and describe the new trends in literature as succinctly and beautifully as he did, and virtually all who have tried to do so have been influenced by his example.

-

dated in some respects, and it gives Stein relatively short space, but useful and interesting in others - particularly Proust and Joyce’s “Ulysses”

-

Wilson’s first book (published 1931) with chapters on Yates, Rimbaud, Eliot, Proust, Stein, and Valery.

-

This book was particularly good with regard to the work of Marcel Proust, but I have read fuller and more convincing accounts of the life of Rimbaud. Three stars.

-

Génial.

-

This book is a classic of literary criticism written more than 85 years ago. The six authors Wilson treats in his essays—Yeats, Valéry, Eliot, Proust, Joyce, Stein—were then at the height of their fame as literary pathbreakers. They shared traits rooted in the Symbolist movement of the previous generation. Wilson sketches this Symbolism in an introductory essay, then returns to it in a final chapter in which he juxtaposes the protagonist of a long prose poem by Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Axel, and the poet Arthur Rimbaud as exemplary of two extremes of existence open to the symbolist. The final section of that chapter offers a cautious, but informed prognosis of the future of literature in which Wilson hopes for a synthesis of Symbolism with the movement it rebelled against, Naturalism. He feels that Joyce’s Ulysses is an example of what this could look like.

Despite its age, I felt the book has held up well. Wilson responds sensitively to good literature and expresses his views in an elegant, clear style. His appreciation is mixed in each case with judicious criticism. Only in the case of Stein does the negative outweigh the positive, but Wilson nevertheless considers her, too, a significant writer.

I’m sure I consulted this many years ago for a paper for a lit course, which always made me think, when I saw it sitting on my shelf, I had read it. But when I looked through it recently, it was evident I had never read it from cover to cover. Better late than never, I guess. -

"Axel's Castle" provides a good introduction to modern literature and its sources in the Symbolist movement. The book is a bit uneven, some writers receive more attention than others; Getrude Stein for example, is covered in only ten pages. It is clear that Wilson views Joyce and Proust as the two most significant modern writers, and the two chapters dealing with them are accordingly the most insightful of the book (and worth the price of the entire volume). Addionally, the book will provide an introduction for most readers to the deservedly obscure Villiers de L'Isle Adam and may impel them to read "Axel". Perhaps the latter volume will someday return to print now that Wilson's first work of literary criticism has finally done so. If you are at all interested in any of these authors or the Symbolist movement, this book is essential as Wilson is one of the foremost literary critics of the century, and this is perhaps his most representative and greatest work.

-

One that I should re-read. I originally got it because I wanted to know what Wilson was writing about

James Joyce's

Finnegans Wake. Early criticism not only on Joyce, but on other modernist writers as well, including

W.B. Yeats,

Marcel Proust and

Gertrude Stein.

Acquired 1985

Cheap Thrills, Montreal, Quebec -

Published in 1931, Wilson takes a look at some of his writer contemporaries (Yeats, T.S. Eliot, Valery, Stein, Proust, and Joyce) and draws out how their works uses Symbolist theories. It is a good introduction to these writers and the techniques they employ. Since I am also quite interested in the Symbolists, I found some enlightening perspectives, such as how the Symbolists differ from the Romantics and bridge over to the Modernists, how the Symbolists turn away from the outside world to focus on the subjective and internal world. Here's a good link for a review contemporaneous to the book:

http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/11/23... -

Lots to muse over in this work of literary criticism. Is French Symbolism in some measure the French equivalent of the poetic practices of Shakespeare and the Metaphysical Poets? Bet that never occurred to you. The book begins with an introductory essay laying out an argument for what precisely Symbolism is and why it occurred and then goes on the explore its' influence on Valery, Proust, Joyce, Yeats, Eliot and Stein. Wilson is a very good writer and the book is not remotely dry. I've read it several times over the years and get more out of it with each reading.