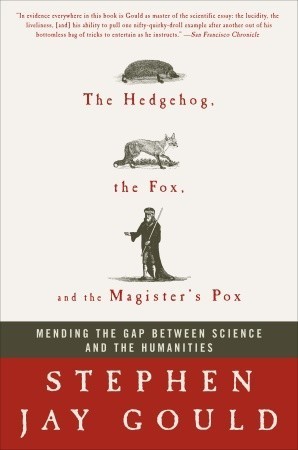

| Title | : | The Hedgehog, the Fox the Magisters Pox: Mending the Gap Between Science the Humanities |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1400051533 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781400051533 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 288 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 2003 |

The Hedgehog, the Fox the Magisters Pox: Mending the Gap Between Science the Humanities Reviews

-

Being dead shouldn't exempt Gould from editing.

-

I had a very up-and-down experience with this book where certain parts fascinated me immensely and others felt like suffering until the next chapter. Gould's first step in mending the gap between the sciences and humanities revolves around establishing mutual respect for both approaches to knowledge and appreciating what types of knowledge each is suited for (observation and empiricism being largely suited to the harder sciences; ethics, morals, culture/art being better studied by the humanities). He goes to great lengths to outline the process of reductionism and the urge to synthesize complex systems under broad theories/definitions. He does a great job tracing the history of the "two cultures", as well as debunking the myth of theology vs. science as being necessarily in opposition. The more he mentioned the hedgehog and fox analogy, the more muddled I thought it became--I am still undecided if this was because I felt I was being beat over the head with it or because Gould had additional points to which my lesser brain was oblivious.

-

While an entertaining read throughout, Gould's final book heats up when he takes on E. O. Wilson's take on consilience, a term coined by William Whewell, an obscure 19th-century English polymath, to refer to a particular kind of scientific induction that does not rely on reductionism.

According to Gould, the sciences and humanities represent distinct ways of knowing, and distinct modes of inquiry. Scientific inquiry will never successfully reduce the humanities into constituent parts that are neatly made up of fundamental sciences such as physics and chemistry. He uses Whewell's elaboration of consilience to attack Wilson and differentiate himself from scientists who hope to one day subsume the humanities. Gould does not spare non-scientists, however, and chides them for not taking full advantage of scientific developments as an aid to problems in philosophy, history, mathematics, literature, and art.

Gould's book also includes many other fine moments derived from his lectures and other books, from which he excerpts liberally. In particular, his discussion of the ancients versus the moderns in Swift's time does a fine job of introducing Swift's famous "sweetness and light" quip to a new generation of academic partisans.

While hardly a timeless classic, and certainly an unfinished manuscript, this book showcases the tremendous breadth of Gould's thinking and suggests what was lost with his death. -

Gould presents his position that people (presumably academicians are the guilty parties here) in the two currently opposing camps of Science and Humanities have a lot to learn from each other and that everyone would benefit if they would only cooperate rather than seek to delegitimize each other's way of thinking. Being a scientist, he places most of the present-day blame on his own colleagues but grants that it can trace its origins to the oppression of science in the early days of the Enlightenment. Much of the latter part of the book is focused on critique of E. O. Wilson's book, Consilience..., which champions a reductionist scientific view as the best method for the furthering of human knowledge.

Gould makes many good points although I feel like he concedes a little too much legitimacy to Religion.

His writing style here is his usual: while not exactly flowery it is always feels forced to me, with a too-clever-by-half complexity that is revealed instantly if one tries reading it out loud. Natural, it ain't. He casts aspersions on the typical lackluster writing style so common among his scientific colleagues and rightly so. But I think his style is flawed in equal magnitude though in a different way. Pinker, Dawkins and E.O. Wilson himself are all much better literary stylists. -

As a student of sociology of scientific knowledge I stand on the precipice, in the midst of an ongoing debate about whether sociology should be a quantitative (a la the natural sciences) or qualitative (more like the humanities) endeavor. I wonder, 'don't we need both, and for different reasons?'

I found this book interesting because I am also reading Dennett's "Darwin's Dangerous Idea". On a side note, it was a great way to brush up on some Latin, and a reiteration in some ways of the Non-Overlapping Magisteria thesis appearing in other works like 'Rocks of Ages'. there is this 'realist versus relativist' debate and the old 'science and religion' relationship which are both central to SSK as heated issues in which the public has become heavily involved. I really appreciate that this book took on some different, lesser-known but highly illuminating perspectives, rather than starting the discussion with a well-worn caricature of Galileo and the Church.

Thank you, Stephen Jay Gould, for providing the framework for a tractable middle ground between the narrow positivism growing in popularity among natural scientists and the postmodern irrationalism that has become fashionable in the humanities. You are missed. -

A tiny little bit too much Gould. Although I like it that he seems to get his pleasure in displaying his knowledge. And his books. He knows Latin and German. Well, not that he knows how to spell schwarz. The hedgehog fox metaphor (from Isiah Berlin) I do not really get. Okay, the hedgehog does know only one trick. But very efficient. Is this science or humanities?

He talks about Snow, the invention of the flat earth. There is no war between humanities and science since one party (science) does not show up. Meaning they are not interested and do not know about any conflict.

A large part of the book is directed against Wilson (nice anecdote about someone pouring water on AW. SJG says he regretted that he did not use violence at the occasion.)

I will try to remember the name Konrad Gessner. The censor of Gessner’s work on animals (everything about pigs e.g.) He crosses out every occurrence of Erasmus. Misses one though, where he talks about the hedgehog/fox. Nice, but too arty. -

I purchased this book at Second Story Books in Washington DC.

I usually love Stephen Jay Gould's books, but I just couldn't get into this one. I can't tell if this is because of the lack of editing by Gould himself, the topic, or the writing coming late in Gould's life, but my eyes just glazed over for the vast majority of the book. I enjoyed the essays in the middle that were reprinted from previous works, but I just didn't understand the overarching thesis for this book.

On the other hand, I enjoyed the Note to the Reader at the beginning of the book as so many times I think to myself (and say to other people) how I wish Gould were alive today. Not just so I could read more popular science on more current topics written in his clever prose, but because we need his measured voice and knowledge in our current polemical climate.

I don't think I'll revisit this book again, but I'm glad I read it once.

Edit: Well, I read it again, and I enjoyed it quite a bit more this time. -

This is one of Gould's last books, full of logorrheic musings on the relationship between science and the humanities. He says that science is not an enemy of religion, not an enemy of "science studies", not an enemy of art, and the people who make the opposite impression are marginal radicals; C. P. Snow's famous essay on the two cultures overgeneralizes a parochial British situation; Vladimir Nabokov was a competent lepidopterist and Ernst Haeckel a great art nouveau illustrator.

-

Gould has a good point in this book about the separation and mutual value of science and the humanities, but it sadly gets lost in the verbiage. Here Gould is at his worst, showing off translation skills, bragging about his book collection, and generally being an obnoxious know-it-all in love with his own language. I love Gould, but this is not a good book.

-

More of a 2.5 (a 2?), but, as my first Gould in years, I can't help but have been charmed by his doddery & genial professor prose.

Framing the titular gap with a short genealogy of modern science and its formation against the backdrop of (and against as a reaction to) Renaissance humanism, Gould builds his way up to his central target: EO Wilson's then contemporary book

Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge which Gould claims expresses a scientist's chauvinism (not his words) to everything not within his own field. Instead of the false binary of scientists vs. humanists, hedgehogs (specialists) vs. foxes (generalists), each should work as a hybrid (foxhog? hedghefox?). Gould's best example is the American painter Abbott Handerson Thayer's contribution to the understanding of how countershading functioned in animal camouflage because of skills learned from painting. Then concludes the book with a heavily theoretical 70-page discussion of the titular concept of "consilience," by sharp contrast.

What caught my eye was a longform anecdote about a public debate regarding Wilson's theory of sociobiology during which Wilson is called a racist and has water poured on him by a group of student activists. Gould's response is to invokes Lenin's "Left-Wing Communism, an Infantile Disorder" against them before defending sociobiology, saying it couldn't spread racism because "the pseudoscientific substrate for racism" is "the causes of geographic based variation" and not "putative human universals." Perhaps more so now, but I feel that even back then this is a bizarre claim. Especially from the same author who wrote

The Mismeasure of Man, a work specifically against race science from my current understanding. This is not to impute sociobiology so much as his method of defending it though.

This is the first book in a while that's made me realize how old and prematurely tired I am. Contextualize this book as 4 years after Toni Morrison was asked in two separate times whether she

"can [imagine] writing a novel not centered around race?" and whether she'd incorporate white characters into her works

"in a substantial way." 8 years after the infamously racist The Bell Curve, '94 Crime Bill, and Hilary Clinton describing Black people as "superpredators." It boggles the mind that we're here and it boggles the mind that one could protest fairly obvious ideas about how bias can effect analysis. Wtf is history.

To come back to Gould. It's clear he wanted to referee the conversation "between the sciences and the humanities" by saying it's a vestigial conversation from a time when the distinction had social value, in this way positioning himself as an Aristotelian moderate/modernizer. It doesn't work. Even his transformation of Wilson's "consilience of reductivism" into one of "equal regard," where the two domains "acknowledges the comparable but distinct worthiness" instead of one being subsumed under the other, reveals the fundamental conflict in taking up this centrist stance: how can there be conversation between sides that don't acknowledge each other's worthiness? Wilson definitionally sees the sciences as the suzerain of the humanities.

Funnily enough, more than ever before, it feels like a moot distinction. Computers

paint paintings and bacteria

are poems. Meanwhile there's still chauvinism about how diverse ways of knowing and experiencing can meaningfully develop scientific study,

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants being just such a work emphasizing this diversity.

There's space here for an interesting discussion of how bureaucracy, Enlightenment rationale -

As a grad student, this feels like listening to the ramblings of your scientist grandpa - partially entertaining from all the obscure anecdotes and grouchy ranting about that science life, partially leaving me scrunching my head over what exactly is he driving at.

I'll cut Gould some slack here, because dying is a valid excuse in my books, but the book really needs a second draft – or an editor doing so much reworking they should be counted as a second author. Some things could have been simply cut out, but I think the general points Gould is making are somewhat funkily arranged and while the metaphor of the hedgehog and the fox has been worked in pretty consistently, the whole thing with the magister's pox is more of an author's curious aside. I am also not entirely sure who this whole thing is for – using multiple methods and approaches to scholarship good, pedantism and censure bad – I mean, no shit?

I am also not sure his examples of science being useful to humanities and humanities being useful to science are that great or demonstrative? Edgar Allan Poe translating some French science texts to publish a more comprehensive mollusk textbook together with some other guys is not really an example of humanities helping science I think (?) – it's just being thorough about information sources. Conversely, Nabokov scholars ignoring what he said about him using moth and butterfly metaphors isn't them ignoring science, it's just cherry-picking sources – it has nothing to do with butterfly research per se?

There was an interesting point about science texts typically avoiding stylistic flair, except when not, but I am not sure Gould is entirely accurate here either – technical texts from the humanities, as few of them as I have seen, are not particularly riveting either. There is a difference between technical publications, broader theoretical works, and popular writing for a lay audience – perhaps things are different in paleontology, but over here in the human sciences it is typical to use dry cut-and-paste formulations for research papers, the methods and the results especially, with more humane writing styles used in many theoretical papers (where the goal is more to convince the audience, rather than lay out some findings), and even more so in popular science books. The results vary, of course, but I not entirely sure the scientists are the only ones at fault here. Modern English overall seems to bend towards simpler, plainer prose, rather than twisty flourishes of the 18-19th centuries.

He talks about consilience a lot, which is a nice term (thanks Whewell) basically referring to cases where a coherent theory is arrived at via insight, rather than progressive experimentation – there was a long ramble about it, and reducationism, but at the end of the day – it's a descriptive term for how some kinds of progress in some cases is/was made. Sometimes experimentation is not a viable method and other methods should be used (until the time when you hopefully have enough understanding of the subject to run experiments, like we are now doing with study of evolution) – again, no shit? Who needs to be persuaded of this? -

Ha habido un enfrentamiento entre la ciencia (sobre todo la ciencia dura) y las humanidades desde que el surgimiento de la ciencia como la conocemos en la actualidad (en Europa en torno al siglo XVI y XVII) --enfrentamiento que se ha introducido también las llamadas humanidades, donde desde las ciencias sociales se ve con suspicacia a las artes--. Gould en este libro analiza este conflicto, para lo cual se sirve de un análisis historiográfico (una herramienta de las humanidades) y plantea que son ministerios separados, que siendo ambas parte del ámbito del conocimiento humano ninguna es superior a la otra y no tienen porque supeditarse entre sí, en una postura por demás conciliadora --de un pensador que dedicó gran parte de su obra a la conciliación y al cuestionamiento; además de su labor como paleontólogo--.

-

As expected, Gould provides an logical and well-written consideration of the common ground between science and humanities. He uses humanities-based reasoning to support science and foundational science to sure up the need for humanities to better the human condition. His lengthy comparison of science and the humanities through their parable-sourced fox and hedgehog provides a whimsical and wonderful vehicle to understand the necessary reliance of one on the other and the inevitable failure of one without the other.

Especially after this past year of trying to destroy science and the humanities, this book holds up well for its age. I enjoyed Gould's challenges to E. O. Wilson, but did not support all of them. It anything, they encouraged me to revisit more of Wilson's writing this year. -

This book is a response to Edward O Wilson's Consilience, which was a much better book. Although I disagree with Gould's thesis, especially how he clings to the statement that Science and Religion are completely compatible, which he dismissively states that he "proved" in an early work, I did find the historical tales that he cites as evidence to be entertaining and informative.

The reader should approach the book as a collection of historical episodes illustrating the conflict between Religion, Humanities, and Science, but the philosophy attempting to glue it together is bunk. -

Gould wrote much like he talked. His prose is dense with parenthetical asides, long footnotes, obscure references, and humorous anecdotes that occurred to him at the time. If you're not used to all that, it can take you a couple of chapters to get in the groove. It's worth the effort, although I imagine his editors double-dosed on Rolaids when he submitted a manuscript. Be prepared.

-

El último capítulo - un magnífico ensayo contra el reduccionismo de EO Wilson - ya justifica el libro, pero en esta relectura merece la pena detenerse en la creación del mito dicotómico (esto es, ciencias vs humanidades) desde Snow, a modo de actualidad y constructo ideológico, hasta, en plena remontada, Bacon.

-

A delightful argument for the keeping the different goals and strengths of science and the humanities rather than attempting to mush them all together as E O Wilson suggested in Consilience.

-

Meh

-

The number 2 is a very dangerous number ... Attempts to divide anything into two ought to be regarded with much suspicion.

-

Review title: Science vs. the humanities in a shrugfest

Gould, while touching briefly on the more headline-grabbing battle between science and religion (which he has apparently tackled in full elsewhere), takes on the science vs. humanities here. My suspicion is that the lack of crackling urgency the topic seems to have today is dependent on two key factors:

1). Science has won! We are all materialists, we are all reductionists; even if we are not all scientists, we see the fruit of science in the technology that dominates our lives today in so many ways--computing in the workplace, pervasive entertainment convergence technology in the home, mobile communications everywhere, once miraculous medical treatments and pharmaceuticals everyday. We even recognize, whether or not explicitly as materialists, that the brain is at the very least a powerful machine driving the mind, which perhaps serves as its operating system which enables us to think, live, create, all those things under the umbrella of the humanities.

2). To a large extent, the division is and has always been an academic one. People living in the real world read, right, watch, admire, create live, in the humanities, while recognizing the value, impact, and reductionist/materialist rightness of science in its proper place. We know the world "works", we need not know or even think about it that hard. Perhaps we are too cavalier in our ignorance of the sciences, but a case could also be made that to the average non-thinking person, even the humanities are a distant land too seldom visited, so why the hub-bub?

Gould's point in this book, which based on these factors seems more dated than the 10 years since its publication, is that science is like the hedgehog, a ":simple-minded" creature in that its only method of self-defense is to curl into ball to surround its soft internal organs with its prickly covering. On the other hand, humanities are like the "wily" fox, with many methods of defense or escape which he crafts to the occasion. Gould calls for both approaches to action to resolve the dilemmas facing the sciences and the humanities, in other words, the world today. He doesn't call for convergence on scientific materialism to resolve problems which is outside the "magisterium" (or realm) of science, such as questions of origin (although Gould reveals a strong bias by condemning Christians who believe the Biblical creation account), morals, ethics, politics , and religion. Rather, he suggests that scientists use the fox's range of methods by becoming well-read and thinking holistically to approach problems that can not be simply addressed through materialism, and that humanists adopted the hedgehog's scientific method to resolve problems in its magisterium when those problems are really amenable to materialism. He also calls for the wisdom to know when.

Gould uses the Magister's Pox of his title as a warning of the inability to solve this conflict by force--in this example the censorship (pox) attempted by the Catholic church to erase the nascent scientists names (not even their ideas, just their names) from a 17th century volume in Gould's personal library. The effort, besides being wrong-minded, turns out to be impossible, in Gould's interesting example.

So the battle may no longer be in full fight, but Gould's reminder still has an impact. -

I am scoring low not because of the writing it'sself, but my own personal rating of enjoyment in reading this book. I gave it all that I had and wanted to commit to completing it, but after getting about halfway through, I found that my life would be no different if I stopped now and picked up something that I would find more fufilling.

I chose this because the parents book club at my daughter's school was reading it, so I wanted to check it out. It's quite wordy, refers to ancient scholars and is just a little more than what I personally can handle. It's great that there are people in the world passionate about science and humanities to this degree, but the presentation style of the topic in this book is not for me.

There were a few comments that were rather humerous, which I enjoyed. -

Through his usual informed and intelligent use of meaningful figures and sayings, Gould makes a good case for the false and ongoing division between the humanities and sciences and presents a resolution. In his conclusion he critiques E. O. Wilson's resolution (presented in Consilience)and counters with his own distinction between consilience and reductionism. He concludes with an affirmation of the important and necessary differences in ways of knowing and what the sciences and humanities can gain from a respectful relationship. I recommend the book for those interested in science, humanities, intellectual history, and the history and philosophy of science.

-

Don't ask me why I'm reading this - or why I've been trying to read it since I bought it way back in something like 2003; let's just say I'm going through my let's find out more about Isaac Newton phase.

Indeed a lot of the books I've been working my way through at the moment have mentioned Newton - including Quicksilver, in which he's plays a key role, to the Lost Symbol, Discovery of Witches and even Rivers of London, in which it turns out he defined magic!!

Anyway, Gould has a dry wit and while much of his narrative does go over my head, there is enough there to keep me interested. -

The historical tidbits are fascinating, the argumentation is mostly sound, and the point the book aims to make -- that the sciences and humanities must be informed by each other -- is noble. But Gould focuses way too much on picking apart E.O. Wilson, and the book ends up being a repetitive litany of reasons to distrust science centrism. His writing style is also suffocating: every sentence seems to have so many twists, turns, and subordinate clauses that by the end I would find myself literally feeling a need to gasp for air.