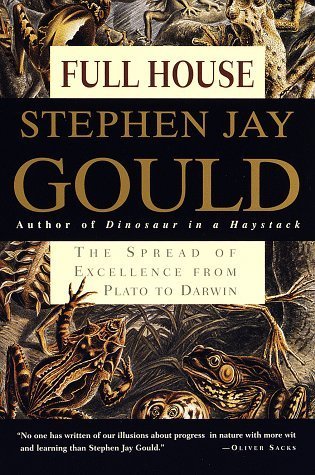

| Title | : | Full House: The Spread of Excellence from Plato to Darwin |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0609801406 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780609801406 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 256 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1996 |

Full House: The Spread of Excellence from Plato to Darwin Reviews

-

Sources of the Divine

In the two decades or so since the publication of Stephen Jay Gould’s Full House , it has attracted attention and criticism from many corners - evolutionary scientists, religious spokespersons, even from some of his allies in promoting humanistic rationality. Gould’s central point is that Darwinian evolution is not a progressive process, specifically that the species Homo sapiens is not the top-most branch of an evolutionary tree. Rather, for Gould, the development of species is more like an expanding spider’s web (my metaphor not Gould’s), stretching out in multiple directions with numerous interconnections which are mutually dependent.

This deconstruction of evolutionary hierarchy - in which ‘later’ is presumed ‘better’ and ‘complex’ is superior to ‘simple’ - is a brilliant insight. So brilliant that I would like to suggest it goes beyond biology. It is an insight which actually accomplishes what religious fundamentalists mistakenly feared about Darwin. Gould provides what is essentially a natural theology, by which I mean he articulates the source of the apparently universal human instinct for contemplating the miracle of their existence. Just how profound a miracle is revealed by Gould’s analysis of the origin and maintenance of life on Earth, both of which depend upon an invisible, effectively omnipotent, beneficent, yet impassive entity: the domain of bacteria.

Bacteria are neither plant nor animal; yet they are necessary for all plant and animal life. Some bacteria have the capacity for photosynthesis; others ‘eat’ various organic and inorganic material in chemical reactions. They stabilise global ecology, create our food, digest our dinners (as well as our oil spills), manufacture our vitamins, consume our waste, and sometimes kill us in large numbers. Some have a more complex genetic structure than human beings. They can even extract DNA from their environment. Bacteria are both top and bottom of the food chain. If all other life disappeared, they could live on each other. We need them but they do not need us.

Bacteria arrived on the planet long before we did; and they will probably outlast us because their mutational processes allow them to adapt quickly to almost any environment. There are consequently a lot more of them than us no matter how you measure it - sheer numbers, gross mass, or prevalence. They are everywhere, on or in everything. Without bacteria, the human species would simply not exist. Collectively bacteria are what we typically mean by the word God - the source and destination of our existence which protects us, and lovingly returns us to the dust whence we came. We are not caretakers of the planet but its in-patients. Bacteria are the ones in charge.

So the biblical story of creation is certainly deficient, as well as species-centric. Even before the command ‘Fiat Lux’ much less the division of the waters and the separation of land, ‘Fiat Prokaryote’ (necessarily mixing Latin and Greek), ‘Let there be bacteria,’ should have sounded. But, of course, bacteria are mute... as far as we know. Then again, so is God - yet another data point suggesting bacterial divinity. Perhaps this was what Spinoza was trying to articulate in his pantheistic philosophy - God everywhere, in everything, the universal divine spark. Even the intuition of the Christian Trinity concisely describes the situation of bacterial dominance: God within us, God among us, God entirely separate from us.

According to Gould “humans can occupy no preferred status as a pinnacle or culmination. Life has always been dominated by its bacterial mode.” It is bacteria which created us and it is bacteria which sustain us. It is bacteria, if anything, that will redeem and save us from the destruction we have wrought on the planet and its other species. Long live the bacteria! Thanks to Gould, we know to whom the religions of the world are really dedicated - or should be. Bacteria are at the centre of the web which is nowhere, and its circumference which is everywhere. The divine bacterial mind is as inscrutable as any mythical figure. It deserves our devoted respect and, who knows, perhaps even our prayers. I’m thinking of a revolutionary mantra: ‘THE FIRST SHALL BE LAST’

Postscript 05082020:

https://apple.news/AINL2c4hURgixtYAvo... -

Dawkins once criticised Gould for being too good a writer. Now, there's a criticism you don't read every day.

This is a stunning book. In it Gould discusses Plato's forms, his fight with cancer and his explanation of evolution as not being about increasing complexity. Prepare to have your fundamental assumptions about evolution shaken to the core.

I love this man's writing - over the years he taught me more about the world than just about anyone else I've ever read. In fact, if there was anyone I would quite like to have been... -

The ideas outlined in this book can easily get a 5-star rating. My understanding of evolution after reading it is entirely different from what it was before doing so. Gould shattered some old concepts and replaced them with powerful and concrete ideas that helped me appreciate life even more so (especially after knowing how improbable our own existence is). There is indeed "grandeur in this view of life".

I deducted one star because of the part about baseball, which was too painful to read for a non-American who doesn't know a thing about the game, but most importantly because the author was repetitious regarding the main premise of the book, i.e. the history of life is void of any drive towards progress when all living things (Full-House) are taken into account. I believe the book could have been shorter, but I won't deny that it was a very enjoyable read. I strongly recommend it to anyone who's interested in Evolution. -

If you think, like a lot of people do, that evolution is a progressive process that moves towards complexity (whatever that means), and, even worse, if you’re a member of a solipsistic species called Homo sapiens who think that they’re the goal and the pinnacle of evolution, you need to read this book. Gould shows that progress is not only NOT the goal of evolution; it’s not even a general trend. The book may also help you with answering another one of the dumb questions asked by the creationists: Why didn’t all apes evolve to become humans? (But why even bother talking to creationists?)

Gould didn’t emphasize this point hard enough, but this book also puts a chill on the enthusiasm of finding intelligent life outside this planet. If there’s a planet that is amenable to life, surely given enough time evolution will produce an intelligent species like us, right? Wrong! As Carl Sagan said in another book, this is like elephants expecting evolution producing an extraterrestrial species with large trunks. We’re just an unpredictable and contingent accident of evolution, not its intended culmination. If you replay the evolution of life over and over again, almost surely we will never appear again.

Gould is very good in statistics – as also proved in The Mismeasurement of Man – and he can spot wrong conclusions from sloppy statistical reasoning very well. If you care enough, you can also learn from this book that why the disappearing of 0.4 hitting in baseball is because the game has improved, not worsened. -

After having defended life's contingency in

Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History, Stephen Jay Gould, this time, strikes again against the misconceived idea that evolution implies any kind of progress. It's not. It is, in fact, all about 'non predictable non directionality' (as he so rightly puts it).

Such fallacy (the belief in life's ascendency, a progress towards something better) when thinking about evolutionary science stems not only from our arrogant anthropocentrism, but, also, our tendency, when looking at systems, to focus more on means and/or extremes than the variations within the said systems. The implications when coming to evolutionary science are crucial. They enable us in fact to change our whole perspective upon the nature of life itself. This may sound dull or complicated, but it's actually very simple to understand. Gould, true to his inimitable style and demeanour, illustrates this basic role of randomness using entertaining examples -from the drunkard's walk to why the disappearance of 0.400 hitting in baseball! The slight digression about bacteria will be just one more nail if necessary into the coffin of the misconceived idea of life's ascendency.

As always with Gould, we have here a fascinating read, both enlightening and entertaining. -

http://nwhyte.livejournal.com/1788521...

In this book, Gould appeals to us to consider the full range of complexity in systems, rather than concentrating on the outliers. His overall point is that while human beings may be particularly complex life forms, that doesn't in itself make us the destined end-point of evolution, which will quite naturally increase the number of more complex organisms because all in all they are not as likely to become less complex.

He bolsters this argument with a rather moving personal testimony about being a cancer survivor, and an excessively lengthy section ( a quarter of the book!) about why baseball will never again see anyone achieve a batting average of 0.400 or better, in which the term "batting average" is nowhere explained, which makes it pretty uninteresting for those of us who know little of baseball. But the other three quarters of the book are good. -

In the prologue Gould promises that this is a short book. It is not short enough. All the arguments and evidence could have been thoroughly covered in a few pages. The book is full of repetition and harping, harping, harping on the same thing. It should have been an article, not a book. But he's right, and I suppose a book reaches a wider and more lay audience than an article. Still, I could have used less baseball and lot less patting himself on the back.

-

Well said, Professor Gould! No, really, very well said indeed. Almost perfect, really. No need to repeat it, I got the idea the first time and . . . well now you’ve gone and said it again in a slightly different way, which makes me wonder if you think I’m some sort of dimwit who needs you to draw me a picture. Oh look, now there’s a picture . . .

That’s my only complaint about this otherwise remarkably entertaining and stimulating book, which lucidly expresses some fascinating ideas that will leave any self-respecting homo sapiens respecting himself a little less and bacteria a little more. Those guys are the dominant species on this planet. Always have been. Always will be. We humans are just a crazy idea evolution got when it stayed up all night smoking crystal meth. Sure, it seemed like a good idea at the time, but in the last three billion years, it’s never improved on bacteria, the megalomaniac delusions of evolution’s latest flight of fancy notwithstanding.

The book’s central theme is crucial to a genuine understanding of evolution. Pardon the shameless self-promotion, but I recently wrote a

blog post about evolution expressing some similar ideas. It was motivated by my frustration with the retort that “language evolves,” in response to my complaints about the cacophonous mangling of our language, largely at the hands, or, mostly, thumbs, of the text-message generation.

As Gould expresses it so well: “we get to a ‘better’ place by removing the ill-adapted, not by actively constructing an improved version.” I think we’d all do well to fully realize that. Evolution is not a conscious, directed march toward perfection. It’s very nearly the opposite of that.

The use of baseball to convey a fairly sophisticated mathematical concept at the heart of his central idea was, in my opinion, clever and effective, though I could see how that entire section would be tedious for anyone who isn’t a fan of either sports or math. I have no interest in sports, but get possibly giddy at the mere sight of lowercase Greek letters, so I found the analogy brilliant, albeit, as noted, a little repetitive and redundant. And possibly iterative. But mostly, he just said the same thing over and over. -

How do I say this properly. Gould is brilliant, and a wonderful writer for starters. I also don't think his approach was wrong with this one. I thought the idea of hitting it out with statistics was a good one. But please too much baseball! If I buy a book referenced under science I want to read more science. I think he either should have lengthened the book to compensate on the science end of it or shortened the baseball reference considerably. I mean really how many pages were really necessary to get that point home? For me? I could have believed him and seen it in three I imagine, but did anyone count the pages in this dedicated to baseball? Eee Gads I get the comparison, great! MOVE ON!

-

A good book with a lot of valuable information. I think that Gould goes on far longer than necessary to make his point, but it's understandable since it goes against traditional thinking, and I imagine he's had to fight quite a bit to promote this concept at all.

-

Probably not one for those without an interest in statistical distributions, but I found it an interesting analysis of the way in which our perception of some effects can mask their true nature - in particular with reference to the idea that evolution drives towards greater complexity. The ideas seem obvious once explained but do run counter to some 'accepted wisdom'

-

A whole new twist on the limits of evolution and how to play the evolutionary game.

-

Gould is slowly replacing EO Wilson in my mind as the best evolutionary biology writer of the 20th century.

This is far from Gould’s most popular book, but what I love so much about it is how it discusses real macroevolutionary phenomena. So many natural history books for the general public will just be a compendium of nerdy facts: “did you know that female black widow spiders eat their mate during sex? Did you know T. rex might’ve been feathered? Did you know we’re all fish? Did you know did you know did you know??” You know, the kinda stuff that makes people think they’re superior scientists but actually means nothing and might make them a worse person (ooh hot tea).

This book discusses things like diversification dynamics, morphological disparity, passive balance active evolution, and tempo and mode of evolution from a statistical perspective - things we discuss in my PhD seminars and journal clubs - in a digestible non-jargon way for a general audience. It felt like real science. This may be an aspect that only appeals to me and other EEB types. But maybe not.

The main message from Full House, as hinted in its title, is to take into account the full spectrum of possibility in anything, rather than just focusing on the mean or average values that people tend to simplify things into. A really heartwarming anecdote at the start of the book is Gould’s personal experience with mesothelioma and being given 8 months to live at the time of diagnosis. His statistical & scientific background put him in position to approach the situation with logic and numbers; this 8 month-estimate is the median value for a dataset that in fact contains very wide “tails” on the left and right sides of a normal distribution. Gould recovered, and two years later in 1985, published an article in Discover magazine called “The Median isn’t the Message”, emphasizing that such estimated life-expectancies, while useful abstractions, do not reflect real-world variation. The article was revered for changing the perspectives of many people who were face to face with cancer at the time. (Gould ultimately died of a different & unrelated cancer in 2002). It set the rest of the book up beautifully, and isn’t a story that a reader easily forgets.

The focus on baseball statistics for the first half was a bit long for me, but I imagine it was all part of drawing in the general audience.

Will definitely be taking suggestions for my next SJ Gould book. -

Stephen Jay Gould was an author of popular science addressing topics in evolution. His specific credentials included his status as a professor of zoology and geology and a specialty in invertebrate paleoclimatology. Despite those increasingly complex academic credentials he wrote very comfortable and deep essays and books. His topics in Full House are several particular aspects of evolution. Fortunately he was writing in a time before this evolution had become as militarized as it appears to be today and despite reviewer comments otherwise he had religious values and as such tended to respect others with religious values. His books always include humor and self-deprecation.

Drawing examples from several of his favorite topics including baseball, Gould addresses the popular misconception that evolution necessarily moves in any direction or necessarily favors either the process that resulted in the human being or any singularly upward trend.

By making the argument that bacteria can rightfully claim to be the dominant life form across the history of Earth as a living planet Gould deliberately disorients those readers who had been taught that humans are dominant .

On a more abstract level he demonstrates a scientific model known as the drunkard's walk. This is a classic thought problem wherein it is shown that if you have an absolute minimum value like zero that all variation must exist at some higher number. The analogy is to a drunken person stumbling out of a bar where if there is a wall to the left of his intended path and therefore his stumbling root must favor the other direction.

The third leg of his argument allows him to use sports mostly baseball to demonstrate not only can there be a right wall where in the variations effectively exist between two values one absolute and the other less easily defined but relatively easy to demonstrate. He has his own argument for why the .4000 hitter has disappeared from professional baseball. There is no absolute reason why this number has become unobtainable but the evidence would suggest that some combination of factors effectively created a right-hand wall.

By combining arguments that are usually easy for a scientifically oriented reader to follow Stephen Gould's Full House walks the careful reader through a sequence of arguments that effectively address a number of problems in understanding the statistics of the evolutionary process.

This is a rereading by me of this particular book. As much as science is moved forward in the 20 years since publication of I believe this content is sufficiently general to still be consistent with more recent finds. More than this I've always found it a pleasure to follow Gould as he helps me to answer questions about evolution and to enjoy myself with his friendly and personal writing style. -

Why are there no 400 hitters in baseball?

Where have all the great composers gone?

How did Gould "beat the odds" regarding his cancer?

Does evolution produce a concept of progress?

These are central questions elegantly answered by Gould in Full House, an exploration of the phenomena that fall out of the variation found in complex systems. Gould shows how some properties of systems can create the illusion of progress and how this myth of progress taints our thinking about the natural world. Gould pushes the reader's conceptual understanding of things like distribution tails and skewness to a much more fundamental level to show how these basic properties can explain the nature of variation for instance regarding the apparent increasing complexity of life.

Gould presumes reasonably that life started with what will be some minimum state of complexity. The standard view is that life got increasingly more complex up until you reach primates but Gould contests this progress as just being a tail of the distribution of complexity. Most life, by quantity, by species count, or by sheer mass is still very much close to that minimum level of complexity as demonstrated by bacteria. If you were to use any standard measurement for quantity or variation we still live in the age of the bacteria but just happen to be the first self-conscious species.

I found his discussion of why there are no great classical composers anymore to also be compelling. It is not the case that the kind of musical genius required to be great is not existent, far from, but that there is a demand of novelty for musical greatness and that most accessible forms of novelty have been exhausted. There may be limited space for large enough stylistic variation for a new great composer to register.

As is often the case with Gould, the text is wordy and borders on the rhetorical. Few avenues of an argument go unexplored which you can take as either thoroughness or pedantry, but I found this book unusually interesting based on my love of statistics. -

The core principles of the Theory of Natural Selection are incredibly simple and easy to understand, but they have astonishing and far reaching implications, and as easy as they are to understand, they are easy to misunderstand and misapply. Sometimes this has been done by overrated jerks like Herbert Spencer and sometimes by smart men like Thomas Huxley who got most of it right, but who were sometimes wrong in serious ways around the edges.

Stephen J Gould was a fine writer of popular science books who had a deep understanding of natural selection and a wonderful ability to convey that understanding in simple comprehensible prose. Most of what I know about evolution, I know from reading Gould's books. I admire him so much that I once tried reading his serious academic book on his famous theory of punctuated equilibrium. It was opaque and jargony in the worst academic style, so that I put it down after two chapters and marveled even more at the lucidity of Gould's popular writing.

In Full House Gould explains how complexity in life forms develops through natural selection as a function of randomness that does not require any sort of natural tendency over time toward more complex forms. Indeed to the extent that any tendency exists at all, it may point away from complexity. Very interesting and in some ways counterintuitive, but I completely bought Gould's argument, which he backs up with numbers and many examples. He tells a parallel story about how a similar phenomenon of randomness acting over time explains the end of .400 hitting in baseball. I like baseball stats as much as the next guy and found this section interesting enough, but it really didn't do anything to explain the main point about evolution.

This book is now over 20 years old and some of the material at the end felt a little dated, but the overall premise of the book is still totally sound, and Gould is such an engaging writer that this book will still be fun to read in another 20 years. -

Stephen Jay Gould is a skeptic's skeptic. Most of his longer form books (as opposed to his wonderful essay collections) deal with some long-held belief in scientific or societal thinking, and then using sometimes tedious statistical analysis to show how said belief is wrong. What's not to love about a man who made a hobby out of trying to break various paradigms of thought?

Sure, he can get a little bit repetitive as he states and restates his thesis and gives detailed re-accounts of points he made just a few pages or chapters ago. And when I used the word 'tedious', I absolutely meant it. The lengths to which Gould goes to prove his hypotheses are quite entertaining in their own rights. And yes, the subject matter itself may seem a bit dry. How exciting can a book about the contrast between opposing ideas concerning the presence or absence of 'progress' in the history of life be?

Now to be sure, I only recommend this book to the nerdiest of academic wannabes. To the kinds of people who find modal dominance and skewed means via extreme variations interesting. Or if those don't float your boat, I'd also recommend this to people who might delight in watching Gould taking an idea that is quite counter-intuitive (that the extinction of 0.400 batters in baseball signifies an improvement in overall play, not a decline) and then proving it quite convincingly true.

That the illusion of 'progress' in evolutionary history now seems more an artifact of human's egocentric perceptions than a natural law is a testament to how thorough and convincing Gould can be when he gets on a role.

And the delight in watching him dance nimbly from point to point to make his case is part of what makes this book so enjoyable. Even if statistical analysis of the modal and average complexity through the history of life isn't your cup of tea. -

Modern bilimi konusunun uzmanı olmayan insanlara anlatmakta en usta isimlerden biri olan Gould'a saygımız sonsuz. Kitap evrim hakkında alışılmadık bir bakış aççısı getiriyor ve insani kendini beğenmişliğimize karşı çıkıyor. Kendimizi saçma bir şekilde evrenin merkezi ve tüm canlıların efendisi ve en yücesi olarak görmemizi haklı olarak eleştiriyor. Konusu ilginç ve anlaşılabilir olmakla birlikte diğer yabancı okurların da sık sık yakındığı gibi çok ağır ilerleyen bir konu dışı örnekleme ile başlıyor. Kitabın ismini okumadan başlarsanız beyzbol hakkında yazıldığını bile düşünebilirsiniz. Bazı şeyleri de ne yazık ki 5 kereye varan tekrarlarla anlatma gereği duyulmuş. Bu kadar fazla tekrara pek gerek olduğunu sanmıyorum.

Evrim hakkında belirli bir bilgi birikimine sahip ve Gould'un yazım tarzını beğenen kimseler için oldukça ilgi çekici olacağını düşünüyorum. -

This was (among) the first books by SJG that were a collection of his articles from Natural History magazine. SJG was the co-author of the concept of "punctuated equilibrium", a kind of refactoring of the basic concept of natural selection first proposed by Darwin, kind of a General Relativity to Newtons 3rd law of motion.

This book is written not towards biologist but lay-folk. SJG is very good at explaining statistics and how the use of statistics is important to the study of evolutionary biology.

A particularly insightful essay in this book gives a wonderfully simple explanation on the continued growth and in diversity and complexity in nature using only a statistical argument.

SJC was one of the greatest and most respected scientist and skeptic of the last century. -

Interesting explanation of how Darwin's theory of evolution accounts for the "full house" of diversity on planet earth without having any tendency towards directionality or progress. Gould has the gift of making difficult subjects accessible to the average reader. In this case, he uses an analysis of baseball statistics and the curious disappearance of the 400 batting average as a way to explain the bell curve. He then uses a similar statistical analysis of evolution to explain how humans are a curious accident at the right tail of the bell curve and not the pinnacle of evolutionary "progress".

-

Gould bets his ‘full house’ against our biased view of natural evolution. Watch out because he is a damn good player. He builds his arguments in such a convincing way making deep thinking not just palatable but exciting and, more importantly, reusable. The whole thing starts revisiting basic statistics concepts using baseball numbers. To ended up with an elegant argument that evolution doesn’t mean increase in complexity. Well, it may feel like a punch in the face since we have been living the age of bacteria for ~3.5 billion years. Yeap, forget dinos and humans; we are just at the right tail of a skewed distribution.

-

Gould's ideas evolved from the early 80s till he death early this millenium, and this book is situated on his time line in the right place to probably be called his best. Wonderful Life was great, but where that sometimes was strident, or dismissive, or just plain had different ideas in it, honestly held at the time, Full House is an opus to WHY life is wonderful: not because of complexity, but because of variety. It's written more confidently, more empathically, and more accessibly. A fitting book to remember the great Dr. Gould with.

-

Always interesting musing from the great paleontologist and evolutionary biologist so sadly taken from us too soon. Topics range widely from why there are no more 400 hitters in baseball to SJG's assertion that we are not living in the "age of mammals", we are living in the "age of bacteria."

Written for a general audience but will probably appeal most to persons with technical training who don't hold with Mark Twain's assertion that "there are lies, damn lies, and statistics." -

Well argued logic with plenty of examples in ecology and paleontology about why variety really is the spice of life. Good follow up to Wonderful Life and reassessment of assumptions we make about Darwinism.

-

An expansive book, even as an adult I know this pushed my "readers' level." Its not a book to be hurried through with complex ideas and complex language but definitely a book that makes you think, that makes you enjoy the process of getting through a book.