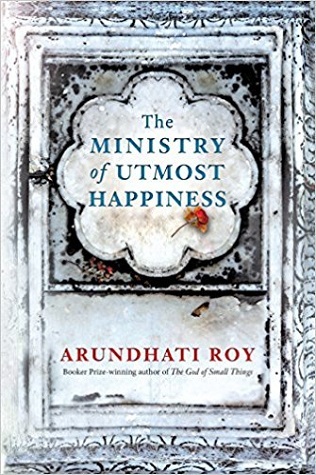

| Title | : | The Ministry of Utmost Happiness |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 067008963X |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780670089635 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 464 |

| Publication | : | First published June 1, 2017 |

| Awards | : | Booker Prize Longlist (2017), National Book Critics Circle Award Fiction (2017), Women's Prize for Fiction Longlist (2018), Andrew Carnegie Medal Fiction (2018), Goodreads Choice Award Fiction (2017) |

Anjum, who used to be Aftab, unrolls a threadbare carpet in a city graveyard that she calls home. A baby appears quite suddenly on a pavement, a little after midnight, in a crib of litter. The enigmatic S. Tilottama is as much of a presence as she is an absence in the lives of the three men who love her.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness Reviews

-

I, like many people, have heard of the success of Roy's

The God of Small Things from twenty years ago. It's been on my mental longlist of books to read since before Goodreads existed. Perhaps it was a mistake to put it off and opt for Roy's newer release instead, but all I can say is my expectations have significantly lowered after reading

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.

At first, I thought the story was slow, dense and hard to follow. It took me a couple hundred pages of squinting hard to see the truth: there is no story.

These kind of books have a special place in the heart of a certain type of reader. A reader who puts beautiful, complex writing over plot and emotional pull; a reader who doesn't mind looking back over almost 500 pages and realizing very little has happened, even if it was told with pretty language.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness essentially follows two main characters in South Asia - Tilo and Anjum - the former is dragged into the center of an independence movement, while the latter is intersex and living among ghosts. However, there is a confusing mess of characters introduced throughout the book and I found it hard to warm to anyone. It is set across the span of many years, through the partition of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, but these times of tremendous upheaval and horror were narrated coldly.

The book is just very difficult to enjoy. It feels deliberately intellectual and lacking in personality. Not only is there a sea of forgettable characters, but the book zips quickly between past and present, third and first person, with almost no dialogue to separate the huge paragraphs of dense description. The book constantly has a foot in several tangents about spiritual anecdotes, diatribes, history lessons and various monologues, each of which went on far too long. When it finally came back to the main issues, it took me a while to get back on track.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is a book without a plot that simply explores the perspectives, past and present, of many characters. That's not necessarily a bad thing, but it's also not the kind of book I enjoy reading. It even feels disjointed, almost like a collection of short stories rather than a novel. I feel like

The God of Small Things is going to be on my TBR a lot longer.

Blog |

Facebook |

Twitter |

Instagram |

Youtube -

This is a novel that captures the life that Arundhati Roy has lived and the issues that have consumed her since the publication of her groundbreaking The God of Small Things. It is a story about our contemporary world, of India, and Pakistan, delivered through the microcosm of individuals living through the never ending and harrowing conflict in Kashmir, and the fringe communities of outsiders in Delhi. It begins with the observation of vultures being eliminated through poison, a metaphor for the way Indian society has been poisoned by a history of corrupt and venal politicians, religious hatreds, and the overflowing rivers of blood and death denied justice. It touches on the issues of caste, divisions based on country, gender and religion, grief, loss, and love. It is a sprawling tale which lacks the steering hand of a plot, so might not suit those looking for a more defined and structured read. I found it a riveting read, infused with humour amidst the horror, and beautifully written with vibrant imagery, underpinned with artistic, lyrical prose.

In Delhi, a mother examines her new born boy, Aftab, only to find the disturbing anatomical female parts. The lonely Aftab grows up to haunt the Hijras, at the transgender centre, convinced that it is more home than his parental home or the rest of society where he cannot be himself. He is taken in and becomes the wildly popular Anjum, who takes in and raises a child, Zainab. We then get to know Tilo, in Kashmir, part of the youth brigades and her friends, a highly placed disenchanted intelligence officer, a journalist and Musa, an activist in the struggle. We see a region mired in infinite death without end. When asked to help Musa, Garson Hobard does so. Trauma causes Anjum to move to a family graveyard and build a home on top of it. It comes to be known as The Jannet Guesthouse, a sanctuary for outsiders and the misfits where no-one is turned away. It is a swirling hotbed for stories as a community springs up, supporting each other and bringing up a baby without the need for blood ties or religious divisions. This Ministry of Utmost Happiness, built on a graveyard, inhabited by minorities and outsiders, is the symbol for hope, peace and compassion amidst war torn Kashmir and for India.

For those who hold opposing political viewpoints to the author, they are unlikely to be enamoured by this book. For me, it has some deep flaws such as the vast array of characters that it is difficult to do justice to. However, its strengths far outweigh its weaknesses. I found it a heartbreaking read when it comes to looking at the history and the current state of India, it is difficult to be optimistic about the future. Amidst the carnage, Roy paints a picture of hope and love through her eccentrics and misfits for whom India offers no home. Who would stand in the way of this literary vision? A stunning and brilliant read that I recommend highly. Thanks to Penguin for an ARC. -

Last year as part of my annual women of color reading challenge, I read international Man Booker award winner The God of Small Things (1999). Full of luscious prose and distinct story telling skills, Arundhati Roy expertly tells her readers a story of life in newly partitioned India. Roy is an author who I would easily race to bring home her new books albeit one issue- following the success of The God of Small Things she did not write another work of fiction. Roy has spent her career as a journalist and award winning non fiction author, until this year, eighteen years later with the publication of The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. As the saying goes, some things are worth the wait.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness can best be categorized as contemporary literary fiction containing Roy's prose in many forms including poetry, letters, composition, dialogue, and her expert story telling skills. Her story begins in the graveyard Jannat Guest Home of Anjum, although we do not find out the setting or full cast of characters until much later. Anjum, born Aftab, is a hijra-- one who is neither masculine or feminine. In India it is said that only hijras enjoy true happiness, however; during Anjum's early life this is farthest from the truth. Shunned by all factions of society for being neither a boy or girl, eventually the newly female Anjum moves into a Khwabgah, a group home for hijras. The group develops a unique comradeship and it is amongst these people that Anjum lives for the rest of her life, either in the Khwabgah or guest house, which she builds for herself later on.

The first third of the novel is Anjum's story with a large cast of characters, each with a distinctive personality and story to tell. I was captivated by this tale and would have been satisfied if the entire novel was about her and later her desire to be a mother; however, the second third of the novel takes on an entirely new twist. Roy regales her readers with the ongoing conflict in Kashmir. She briefly touches on this when a group at the Khwabgah watches the 9-11 terrorist attacks unfold on television. The hijras are unfazed by events taking place on the other side of the world, but various Muslim and Sikh cells have been plotting secessionist movements in Kashmir since the 1980s.

Roy develops an entirely new plot with protagonists Tilo, Musa, Naga, and "Garson Hobart", who met at university; as well as sinister antagonist Commander Amrik Singh. Each comes from a distinct caste and are the unlikeliest of companions, yet a theater class brought them together, and they remain connected for the duration of their lives. The four play key roles in the free Kashmir movement, a life of terrorism, violence, human rights abuses, and too many funerals. A low point of the novel occurs with the story of the murder of Musa's three year old daughter, Miss Jebeen and his wife Arifa, one that tugged on both my and Tilo's heartstrings as Musa recounted it to her. He relates the line that stays with me the most, that in India, only the dead are living, and only the living are dead. To Musa, the murder was an inevitable part of war, yet, to Tilo, an event that sparked her maternal instinct to be a mother.

The two plot lines converge as both Tilo and Anjum desire to save an unclaimed newborn baby in Delhi proper. Each woman would love to raise this child in a life free of the conflicts plaguing India, that unfortunately continue until this day. Ironically, this utmost happiness occurs in Anjum's communal Jannat Guest House in a graveyard, where a community of outcasts band together in harmony, and to raise an otherwise unwanted child. Throughout all of her storytelling, Roy deftly employs various forms of writing techniques to paint a picture of hope in India, one that had me mesmerized from her beginning words until the ending chords. I grew attached to Anjum, only to feel for Tilo, and then the story continues to begin anew.

I would not be surprised if one day Arundhati Roy won the Nobel Prize for her life body of literary work. Her two novels are that powerful and each tell a captivating story of a distinct era in Indian history. While The Ministry of Utmost Happiness can be disjointed at times as one navigates through multiple plots and an extended cast of characters, the writing is excellent and holds attention throughout. Anjum, Tilo, and company are characters that I will remember for a long time. Hopefully we will not have to wait a full eighteen years for Roy's next work, but in the meantime, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is a scintillating 4.5 stars. -

2017 Award for the Read I was Most Afraid to Dislike

I can't go on. I have spent hours getting to 50 percent. I can't do it.

This book is draining me despite a few passages of immense brilliance.

My Infinite Jest of 2017 and because I can't finish it...likely my worst read.

A new title for me is :

The Ministry of Utmost Frustration !! -

Inner dialogue while reading The Ministry Of Utmost Happiness:

This is fun

Oh this is sad

This is boring

This is boring

Who is this?

Skip ahead to the part about the interesting character

Shit now I don't know who they're talking about

Go back

This is boring

Skip ahead again

Skim

Skim

Skim

Only 48% through?!

It's a Man Booker keep going

Sigh

These judges always do this to me

Finish reading in my car

It's hot

I'm done

Next... -

When the harp begins to sing and the guitar begins to harp, things change dramatically! That is why the book by A Roy has become a dramatic monologue of the ideas and innuendos that she often offers off the books. Reference to the past events are always the best way to write a novel; however, a subtle mechanism behind recalling the events of the past and making them sound like one wants to does call for a scrutiny! Roy's thoughts against the Indian state are well-known. Nevertheless, one (a reader of fiction, including myself) could not expect her doing the same in her fiction too. All the things, except the heart-rendering protagonist and her/his plight to a genuine level, seem genuinely verbose and breast-beating against a certain line of idea. The people who like this are the supposed audience and those who don't like it are the real protagonist of the novel. This was not expected of her. I could do best by rating this novel one but did not do because I respect the 'author of fiction'! And technically, the novel is too lengthy for the theme she has chosen; she could do the same peddling even in a 200-paged book!

-

464 pages of utter garbage (organic as well as inorganic) against the Indian state as well as the popular belief, this is what the book offers you. Unless you are an ardent follower of the ideas that Arundhati Roy usually offers as a perfect example of hired gun by the people with vested interest, there is nothing in this book for you. So, don't be a reader like many including me who have wasted our money and time reading this unworthy material. You can read more about this book on the link below:

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness Review -

This is one of the trickiest books to review because it is good and bad at the same time; likeable and non-likeable at the same time. Fans of Roy should expect a novel that is so unlike its predecessor.

The writing is beautiful, (more grim and dingy compared to The God of Small things) and Roy has managed to fit in almost all the problems of India, both political and social. The plot is weak, characters lack depth and the book could have been easily shorter. But on the other hand the book gives a quick glimpse at everything around the present India. This is something I really enjoyed because the incidents in the novel are happening RIGHT NOW and the reader can relate to almost all of them. This makes the book a profound read inspite of many drifting ends. Also, this is a book that will grow on you after you finish it

Read the complete review to decide if the book would suit you -

http://www.thebooksatchel.com/ministr... -

Click here to watch a video review of this book on my channel, From Beginning to Bookend.

-

[Originally appeared here:

http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/li...]

How does a lament sound? Like a distorted sonorous wave? Hitting the crest with a shrill cry and falling to quietude with mangled whimpers? Or like a prolonged stream of soiled garble, comprehensible only to its beholder?

I don't know on which note of the spectrum this book might fit in, but I do know that this book is a lament - lament on the daily struggles for (dignified) survival borne by the scarred populace of war-torn Kashmir, which unfortunately I can't talk of in past tense, and the marginalized of the society (taking the transgender as the pivotal link).

The book, from where I see, is about two characters - A transgender, Anjum and a riot victim, Tilottama. Anjum, born Aftab in Old Delhi but discarded by her family for socially- unacceptable biological makeup, is adopted by a whore-house. She lives a good part of her life here before shifting her residence to a graveyard, courtesy a grave altercation related to adoption and rearing of a girl child. Tilottama, on the other hand, begins as a firebrand member of the youth brigade in a posh South Delhi locality but eventually drifts, amid three of her friends and her own dichotomies, to Kashmir and the city's deep, unknown, frequently fatal, alleys. How life, with her own surprises and shocks, brings the two together rounds up the story.

This book, only second from Roy's stable in the last twenty years, retains the metaphorical music that she used to fair rapture in her first book. The descriptions, spring to life with her subtle touch, and she, almost, looks to have done that effortlessly.But regardless of what admonition and punishment awaited him, Aftab would return to his post stubbornly, day after day. It was the only place in his world where he felt the air made way for him. When he arrived, it seemed to shift, to slide over, like a school friend making room for him on a classroom bench.

Roy's characteristic insight into her world's props and their subtle breaths is amply visible. She weaves intricate patterns, just like the stunning Kashmiri carpets she refers to couple of times, around her characters and one gets to see a motley crew doing their part well. The three friends, all of them men, who walk in and out of Tilo's life, represent the various facets of the societal fabric Roy wishes to highlight - Biplab is a senior officer in Intelligence Bureau, Naga is an incendiary journalist and Musa, an activist or terrorist (depending on the way you would like to see).She sensed that in some strange tangential way, he needed her shade as much as she needed his. And she had learned from experience that Need was a warehouse that could accommodate a considerable amount of cruelty.

But she gets carried away. She touches upon issues of untouchability and gender divide, fanaticism and terrorism, but they emerge only as matter-of-factly. There are long stretches of pages which are dedicated to the haunting memories of Tilottama, which, at first grab our hearts and hold them in their throes, but soon, they become a necessary vent which loses both on emotional as well as novelty quotient. Anjum, in particular, is crafted with a lot of fragility and I would have loved to read a little more about her but Roy had another strong motive to accommodate. Those who are familiar with her political stances, which she has diligently championed across the various articles, non-fiction works and speeches she has put forward, would detect that a lot in this book comes shrouded in her disdain towards the state machinery and its administrators. Place as she might her contempt amid very many chapters, it comes straight out, and with a vengeance. The military establishments, too, come under attack and she holds very few guns back in lambasting their integrity. While she visibly tones down in the second half through the long monologues emanating from Biplab's hours of prophecy, she doesn't quite miss the diatribe train to dispatch her venom. Perhaps, that's why, even for someone fairly apolitical as I, the work didn't pass by without glaring its political face at close proximity to me.

Those viewing the work from a political prism will mostly react in an emphatic manner - whether in support or opposition will depend on their political inclinations. But those looking from an emotional prism will also not be disappointed - she amalgamates the calm and the turbulent of her world with experienced rendition.Normality in our part of the world is a bit like a boiled egg: its humdrum surface conceals at its heart a yolk of egregious violence. In battle , Musa told Tilo, enemies can't break your spirit, only friends can.

The book teeters over its bumpy rides with seething heart and clamped teeth, and comes to a standstill in the culminating chapters where a certain ray of hope and perpetuity leaps into the air. The quietness of the

shikara stands in stark contrast to the rippling graveyard that is celebrating a wedding, and one doesn't still know where the lament erupted from and where it died down. Or if it is still wailing.

[Note: Thanks to Netgalley, Arundhati Roy and Penguin Books (UK) for providing me an ARC.]

---

Also on my blog. -

Truly, this is a remarkable creation, a story both intimate and international, swelling with comedy and outrage, a tale that cradles the world’s most fragile people even while it assaults the Subcontinent’s most brutal villains.

It will not convert Roy’s political enemies, but it will surely blast past them. Here are sentences that feel athletic enough to sprint on for pages, feinting in different directions at once, dropping disparate allusions, tossing off witty asides, refracting competing ironies. This is writing that swirls so hypnotically that it doesn’t feel like words on paper so much as ink in water. Every paragraph dares you to keep up, forcing you finally to stop asking questions, to stop grasping for chronology and just. . . .

To read the rest of this review, go The Washington Post:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/entert... -

The Millstone of Unfair Expectations

I am, by nature, a punctual person. I was very late to one novelistic Roy party and relatively early to the next. But in this case, it was the one I was late for that I enjoyed.

In 2014, I finally read The God of Small Things, Roy’s award-winning and (then) only novel, published nearly 20 years earlier. I loved it: the lyrical mysticism, the layers of meaning and metaphor, the tangled plot, the complex characters, and the rich but unfamiliar setting. See my review

HERE for why.

News that she’d finally written another novel (this) filled me with joy and excitement. I was conscious that it had a lot to live up to, but was eager to read it. Then I saw a trickle of very conflicting reviews from trusted GR friends. But I won a free copy in a GR giveaway. Fate?

The Misery of Most Unhappiness

It pains me that I gave up on this book a little over one third through. There are flickers of beautiful writing, and interesting characters that I cared about. I suspect the different threads of the story eventually weave a wondrous tapestry, and I would probably discover the significance of recurring saffron and parakeets (the vultures are more obvious).

But…

There are many buts.

Overall, it's a confusing, disjointed, inelegant muddle, with lengthy diversions into ideological and ecological rants and subplots, and with the narrative switching between novelistic, mystical, journalese, and political tract. The chapter where I abandoned it added letters, adverts, and a Kashmiri-English alphabet to the mix. All of those things can work. But here, for me, they don't. It was just too much.

And the politics. This is what Roy has devoted herself to in the years between her two novels. I admire her devotion to advocacy for marginalised groups, but I was hampered by my relative ignorance of Indian issues. I felt this a bit with Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (see my review

HERE), with which this has more than a few similarities (including a child born at midnight), but Rushdie made it more digestible for ill-informed readers like me. And his storytelling was consistently magical.

This novel is dedicated “To The Unconsoled”. Is it heretical appropriation to consider myself a little unconsoled?

The Mirror of Most Transformation

This is about people reinventing themselves, as Roy certainly has. That is an inspiring and positive message and is what I will try to take away from my partial reading. The transformations include:

• A woman trapped in a man’s body.

• An adoptive mother who tries to “transfuse herself into [child’s] memory and consciousness… so that they could belong to each other completely” and to rewrite her life to please her child and make herself “a simpler, happier person”.

• “A revolutionary trapped in an accountant’s mind.”

• A man who adopts the name Saddam Hussein because he admires the courage to do what needed to be done and to face the fatal consequences with dignity “I want to be this kind of bastard”!

• An abandoned baby girl raised by a moderately wealthy woman.

• An irreverent, iconoclastic student who becomes an unemployable intellectual, and then a mainstream journalist.

The Mix of Uncertain Gender

“Holy Souls trapped in the wrong bodies”

One of the main characters is a

Hijra: a term used in India for those who, in the UK, might identify as trans women. Her life is especially intriguing, and sensitively and insightfully portrayed.

The fact of their existence is apparently broadly accepted and unquestioned. The attitudes towards them are more mixed: they have a degree of protection because it’s thought unlucky to harm them. As long as they keep to the margins of society, with a few elevated to celebrity status, most get by, despite the perpetual risk of “harassment and humiliation (of being seen as well as of being unseen)”.

Some of the more negative attitudes seem to come from the Hijra themselves: “We’re jackals who feed off other people’s happiness”, who were created by God as “an experiment… a living creature that is incapable of happiness” because their war is internal, and thus they can’t escape it.

This leads to more existential analysis:

“She fell through a crack between the world she knew and worlds she did not know existed.”

“Was it possible to live outside language?” - when in Urdu, everything has a gender.

The Minimum of Utmost Quotes

• “She recognised loneliness… And she had learned… that Need was a warehouse that could accommodate a considerable amount of cruelty.”

• “The fan had human qualities - she was coy, moody and unpredictable.”

• “The Mouse [nickname of abandoned child] absorbs love like sand absorbs the sea.”

• “In the hissing blue light of the… lantern [his] face looked like a dried riverbed.”

• “Her steadfast commitment to an exaggerated, outrageous kind of femininity made the real, biological women… look cloudy and dispersed.”

• “To be present in history, even as nothing more than a chuckle, was a universe away from being absent from it.”

• “It was an unprepossessing graveyard.”

• “The smack addicts… shadows just a deeper shade of night… clots of homeless people sat around fires… stray dogs in better health than the humans.”

• “A ravaged, feral spectre, out-haunting every djinn and spirit” - the overwhelming effect of grief and undiagnosed PTSD.

• “She lay in a pool of light, under a column of neon-lit mosquitoes… She had already learned that tears, her tears at least, were futile.” (An abandoned baby who is then described as symbolic of the city in general and slum clearance in particular.)

• “[Journalists] asking urgent, empty questions; they asked the poor what it was like to be poor… The TV channels… never ran out of despair.”

• “He who believed he was always right. She who knew she was all wrong… augmented by her ambiguity.”

• “The fog is hunched up against the window panes.”

• “Candidly homosexual, although he never brought it up in conversation.”

• “Something about the stillness of this hastily abandoned space makes it look like a frozen frame in a moving picture. It seems to contain the geometry of motion… The absence of the person who lived here is so real, so palpable, that it is almost a presence” -

By standards of a conventional novel, this is a failure. It is one of the most interesting failures I've read. It's a sprawling, ambitious novel with no plot. Many of the elements of modern India--Dalit and hijra rights, the occupation of Kashmir, tribal land enclosures, Hindu fundamentalism, Maoist uprisings--are here. It's alive on every page.

This is bound to piss off far-right patriots and nationalists of every stripe. It will probably also piss off people who read solely for entertainment and need a beginning, middle, and an end.

There are some reservations I have about this and her politics. Maybe my quibble is that she doesn't go far enough. I could have done without the "one baby to unite them all" thread. I'm guessing that this is what Roy and her editors feel they have to give readers who demand some sense of "closure". So that's my biggest issue with the book: at heart it's about radical politics, but it acquiesces to conservative notions of art and what a novel should be, maybe? I'm not sure.

But if this is what failed fiction looks like--attentive to the dispossessed, the marginalised, and the oppressed; fractured, broken, and sprawling--then I'll take it over polite, well-mannered, perfectly-executed fiction any day. -

هذه رواية فاتنة، من أيّ زاوية نظرتَ إليها.

إنها متاهة حقيقية، كما أطلقت عليها صحيفة الإندبندنت، تنتشرُ أفقيًا دون أن تعدم ذلك السقوط اللولبي في اللحظات الفارقة، تلك التي ساهمت في تشكيل شخوصها وجعلهم من هم عليه. تقدم الرواية لوحة بانورامية على تاريخ الهند؛ تعالج قضايا الطبقية والهوية الدينية والجنسية والعنف الطائفي، ولكنها في الوقت ذاته لا تخلو من طرافة، من حسٍّ متهكّمٍ مر، تشعر بأن شفتي الكاتبة تلتويان في ابتسامةٍ (مرّة قليلًا، لكنها ابتسامة) مع كل سطر.

لا أحب إقامة علاقة بين الأساليب، لكنني لم أستطع عدم الربط بين أسلوب غارسيا ماركيز في "مئة عام من العزلة" وبين "وزارة السعادة القصوى". براعة السرد، قدرة الكاتبة على إيهامنا بأمر ثم مباغتتنا بآخر. التوظيف شديد الأناقة لـ تقنية "الفلاش فوروورد" التي تجعلك تعرفُ، وأحيانًا تحدس، ما سوف يحدث ومع ذلك تبقى مجذوبًا إلى النص، مشدودًا إليه بجميع حواسك. المكان بحضوره الحسي، المفارق، والميتافيزيقي أحيانًا؛ في استعارات وصور مقتبسة من الغابات والمقابر والسجون ومعتقلات التعذيب. الانتشار الأفقي للزمن دون السقوط في فخ التأريخ والتوثيق، ومع ذلك هي وثيقة.. متخيلة نعم، لكنها وثيقة لما وصل إليه هذا العالم من انحدار. إدانة للفساد السياسي، وتوحّش الرأسمالية.. وكل ذلك من خلال متوالية من المفارقات المضحكة، المؤلمة، التي تجعلك تقهقه وحيدًا، أو تزمُّ شفتيك آسفًا.

الرواية من 600 صفحة، وأنا لستُ من النوع الذي يتورط في كتابٍ ممل. إذا مللت، أترك الكتاب وأقفز إلى آخر. لكنني لم أكن مضطرة إلى ذلك. 600 صفحة كانت من البهجة الخالصة؛ كمعالجة، وتقنيات، وخفة ظل مطلوبة في ظل واقع قاتم. ولحظات إنسانية فارقة، عندما تبدأ تلك الشخصيات بالتوهج، من خلال الخيارات التي تتخذها لكي تنجو، وتُحِب، وتُحَب.

قرأتُ الرواية بتوجس، إذ كنت أتخيل دائمًا بأن "إله الأشياء الصغيرة" هي عمل من العظمة بحيث يليق به أن يكون "العمل الوحيد" لكاتبته. بعد عشرين سنة من الصمت تأتي أروندهاتي روي بملحمة من نوع آخر. كم أحب هذه الكاتبة! -

DNF - No rating

Several days ago I posted that I was considering giving up on this book. I very rarely DNF anything, and it pained me to consider quitting this highly anticipated novel. I rather enjoyed Roy's previous novel,

The God of Small Things, and I am always drawn to books that will teach me something about another culture. I don't mind a challenge. However, I was not simply challenged - I was befuddled. I wasn't sure what the author was trying to deliver. It seems that my background on more recent Indian politics is extremely lacking. Which is okay, I would have liked to have been educated on the topic. But perhaps Roy was counting on me to have done some of my own research beforehand. I just couldn't get a handle on the recent historical events. The characters were very interesting, and I would have liked to learn more about them. However, at the one-third point in this book, I felt like I had to wade through too much unknown territory in order to make some attempt to connect with the people with whom I was becoming acquainted. The prose at times was quite dazzling and for this I was grateful. But, I had promised myself that 2018 would see some changes in my reading habits - the main one being that I would read books that would feel truly rewarding or that would provide some healthy dose of just good old-fashioned entertainment. This book, sadly, was not either of those things. Should Ms. Roy decide to pen another novel in the future, I will not discount it. I can't deny her talent, but we just didn't click this time around. -

I was in school in 1997-98, living in a small township. Most of my reading was limited to the age-appropriate fare on offer at our school library, which I had far outgrown (and read twice over). All of a sudden, this new book by an unheard of Indian author was being covered by the print media (and the one TV news program), and it felt like a good bet to spend my hard-earned pocket money on. The hardcover cost about Rs. 400, which seemed like a big amount for someone who had only bought 2nd-hand Archie comic books before that. In my most impulsive purchase till then, I went ahead and bought TGoST in my next visit to the nearest town.

I started reading the book right there while waiting for my parents to get their own (non-book-related) shopping done, continued to read through most of the lunch, and on our trip back home, and late into the night. I cried when Ammu said 'Naaley'. Partly because the book had ended. Partly because nothing I had read had ever hit me so hard before that. Not much has since then either.

I have loved Arundhati Roy's first and, for a long time, only work of fiction deeply. It's the only novel I have read several times, and probably loved it more each time I have read it. It was the book that sustained me when I lived the life of a hermit preparing for my college entrance exams. That precious copy I had bought in school was gifted to my closest friend in engineering college. A number of other copies were bought after that and gifted to people dear to me. Heck, it was even my topic when I prepared for a version of Mastermind for our college quizzing club. And I tend to judge people often by whether they like the book or not.

So this 20-year wait for her next novel has been excruciatingly long. From what I have figured over this period from her nonfiction writing, even if she had written a book with a blindfold on, I would have found it difficult to completely dislike it.

With that hideously long preamble done, let me happily state that I mostly loved this novel too. Her crazy word play, those lovingly constructed characters, their heart-breaking relationships, surviving and not surviving through what time, geography and the Indian Government throw at them, are all there. At over 400 pages, it is not a short novel by any standards, but my interest never flagged (big deal for me) and I finished it in one sitting (even bigger deal).

(I don't talk about the story itself, but talk about the basic themes, but some readers might find even that a spoiler this early in the book's release history, so beware.)

The novel starts off in Old Delhi and spends a long time with a group of kinnars ('eunuchs' would probably be the literal, but impolite, translation). And then almost suddenly changes track and moves to Kashmir, with another set of characters. As one would expect, it all ties up eventually, but I would have liked to spend more time with the Delhi crowd (probably the only time I would say that about any Delhi crowd). In any case, members of the entire cast, even the least important ones, are beautifully realized. (Like Ammu in TGoST, there is a prominent character here too inspired in many ways by Roy herself.) This, I feel, is Roy's great strength. No matter how idiosyncratic the characters might be, they seem way too real, like you know them, and so, are worth caring for.

Roy's even greater strength is the relationships. Because, like the previous novel, this one is also primarily about love. Love in its many many weird manifestations, between humans, humans and animals, humans and dead humans, humans and dead animals, and well you get the idea. I would like to swear that I have grown older in the last 20 years, less susceptible to those tear-jerking tricks that authors employ. But like Frank Capra movies, Ms Roy's writing does some things that I can't explain.

So I will remain a fanboy for now. Readers strongly opposed to Roy's political views might have a more difficult task at their hands with this book though, because the novel covers the whole gamut of issues dear to her - Kashmir (the main plot), naxalism, capitalism, casteism, Gujarat riots, 1984 riots, rise of Hindu nationalism, and maybe more - and generally takes a stand not conforming to the widely held middle and upper class, 'mainland', view prevalent these days in India.

Even for me, who appreciates Roy's contrarian stands, without always completely agreeing with them, the novel seemed to edge very close to becoming a propaganda tool first and a novel as an afterthought in places. Heck, she even uses the phrase 'algebra of infinite justice' at a point. Some of her other book titles might also find mention, but I was not looking closely.

There are unflattering depictions of characters based on AB Vajpayee, Manmohan Singh, Anna Hazare and Arvind Kejriwal. And, of course, Roy's favorite Gujarat's Lalla, who happens to be a very popular PM currently. For these reasons, it won't be surprising if in the way things are handled these days (in India and in many other parts of the world), there would be widespread criticism of the book (some nutcase might even call for its banning!) by many who haven't even read it.

We tend to be particularly sensitive to how India is portrayed in front of foreigners, and this litany of accusations (which is the only thing many might see here), this criticism of the 'stupidification' of the country, might seem like too much bad PR by a book that is bound to be feted and translated all over. That is, in fact, the only reason why these issues would antagonize most Indians. Otherwise, partly because these issues have been raised much too often already by the media and other authors, and partly because those who will generally read the book are fortunate to lead fairly comfortable lives, we have long become immune to them. -

How to review The Ministry of Utmost Happiness? It is indeed a tough feat because it's such a complex novel. And at the same time it lacks so much that I really struggled to follow what was happening.

Having previously attempted to read Roy's debut (and Booker winning) novel,

The God of Small Things, and not finished it, I'm actually quite surprised I ended up completing her second (and longer) one.

But this book had so much potential. So much! I really never wanted to stop reading it, even when I was confused on who was talking or what was happening or if we were in the present or past or future. Roy's writing style, though in this one heavily dependent on cultural and political references, is delightful. Underneath it all—underneath the grim and depressing and darkness that comes with writing about "the Unconsoled" (to whom the book is dedicated)—there is a sort of whimsy. Roy's truly an excellent writer, I just wish she'd had a better editor.

I won't complain about this book's length because 440 pages isn't necessarily too long. But it is when there isn't a clear direction, and that's what I felt this book lacked most. I would've been completely on board if this had been solely the narrative of Anjum, a hijra (transgender woman), or if it had only told the story of Tilo and the three men who loved her. But Roy tries to pack so much into this novel—aside from her fictional characters' stories she includes a lot of historical elements—that it becomes very messy.

Again, I think this could've been a much better read, maybe even 5 stars, with the right editing. Sadly, it became a story that, while I didn't want to put it down in the moment, will probably not stick with me for very long. -

Sanctuary

Arundhati Roy has written an extensive, absorbing and heartbreaking story of the personal struggle of an intersexual person against prejudice and resentment. Set amongst the internal social turmoil of India and the cultural conflict with Pakistan, Roy’s writing is wonderfully poetic and often political.

An eagerly awaiting mother praying for the safe delivery of her son Aftab finds on inspection that he has female parts. Her reactions go from horror wanting to kill herself and her child to lovingly holding him “while she fell through a crack between the world she knew, and the worlds she did not know existed.”

He was a Hijra, and she kept it hidden from everyone for a long time. But you can only hold secrets like this for so long, and eventually, once revealed, Aftab, at 15-years-old enters the Khwabgah (a transgender centre) in Delhi to live amongst the community of Hijras for more than 30 years. With a name change to Anjum, she has had a botched operation that removed the male parts, but it did deliver her the freedom she desired.

India and Pakistan, for many outsiders, are technology-focused global powerhouses yet are such tumultuous, divisive and intractable societies. Their ongoing aggressive relationship has caused conflict that has cost millions of lives, particularly in the Kashmir region. Internally the religious and caste divides are heart-breaking, with the brunt being borne by the lower and minority classes. There are multiple tales in the book with a wonderful array of characters, and they touch on the caste system and the endless killings and retribution. Unnecessary death is a given, and it journeys through the narration with us - ever-present.

Following a traumatic conflict experience, Anjum returns to Khwabgah only to set in motion the construction of a guest house called Jannat (Paradise) on the site of a graveyard. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness guest house will become the home to Hijras and all those unfortunates regardless of race, colour, creed or gender. This will be a haven where all can freely express themselves without discrimination or judgment. While despair, rejection and abandonment are so prevalent in the novel, it is also a story of hope, a story of community caring, and social conscience so you are not alone and unloved. Everything will turn out all right in the end because it must.

I did feel disconnected from the storyline for large sections of the book while it just rambled along. I wanted to see something more happen, especially in the second half. The book is quite long, so perhaps this also added to my angst.

Many thanks to Penguin Books (UK) Publishing and NetGalley for an ARC version of the book in return for an honest review. -

A house divided against itself cannot stand, we are told, yet it is surprising how long they do, inertia maybe - the old world has died and the new one waits to be born, or something like that.

I felt that this was a nineteenth century novel that had rather improbably emerged into the the light of the 21st century, it is passionate and engaged, but also is sprawling and determined to pack everything in, the multiplicity of voices reminded me of Dostoevsky as understood by Bakhtin; and one way to see this book is as a carnival of its characters.

Two central symbols determine the book, firstly the hermaphrodite character is told in childhood by an adult Hijra that they are people who can never be happy. Their bodies wage war on themselves. Problems for other people are external, they may flare up, but then they die down; for the Hijra however "the price rise & school admissions & beating husbands & cheating wives are all inside is. The riot is inside us. The war is inside us. Indo-Pak is inside us. It will never settle down. It can't." (p.23)

The figure of the Hijra for Roy is the central symbol, they symbolise modern India, a state at war with itself because of its nature, a struggle which by analogy can never be resolved ( except either by death or radical transformation). And the rest of the novel follows on from this analogy.

In passing I'll observe that Roy throughout the novel foregrounds the experiences of those whose voices are not heard or when they are heard - as in the case of the Hijra - only through stereotypical narratives which deny each individual's own stories.

The second great symbol is the optimistic one of the old graveyard which here becomes the place where the minorities of the current world can find safety, and together can become a found family whose mutual support suggests the hope of a new society, maybe even a new India. "Each of the listeners recognized, in their separate ways, something of themselves & their own stories, their own Indo-Pak, in the story of this unknown, faraway woman who was no longer alive. It made them close ranks around Miss Jebeen the Second like a formation of trees, or adult elephants - an impenetrable fortress in which she, unlike her biological mother, would grow up protected & loved." (P.426)

What I like about this is that Roy compared with

the God of small things seems to be finally letting her hair down, but as you might expect, when somebody lets their hair down the result is not neat and tidy and disciplined.

On the one hand the particulars of Roy's stories seem very India specific, on the other one can see that systemic prejudice and or oppression, surveillance and intractable internal military conflicts are hardly unique, nor not even so unusual. -

This is my first book read in the Women's Prize for Fiction longlist.

I can both acknowledge and deny the power of this book. It is a novel without a story. It is a story without a narrative. It is about everything and focused on nothing. And not knowing this sooner formed much of my early discontent with a novel that defied its own noun's traditions at every possible junction.

Beautiful penmanship trumps all, for me. And yet in a book that seemed the very definition of what that means, I found it hard to appreciate when there was no substance to back up what it was detailing. I found this lack of, well, tradition I guess, almost infuriating. It was like this book was written with water for ink and the the reader is encouraged to squint their eyes and detect whatever details they can from it and formulate this into a semblance of an original, complete thing. Some can be excited with the innovation and cleverness of this and others, like myself, will end up merely overwhelmed with wet fingertips.

I received a copy of this book in exchange for an honest review. Thank you to the author, Arundhati Roy, and the publisher, Knopf, for this opportunity. -

Expectations would be your vilest villain if you venture into The Ministry of Utmost Happiness wanting to relive that oh-so-delicious reading of The God of Small Things. As the cliché goes, a rude shock would awaken you if you were that naive. You have to understand that Arundhati has switched professions and is now more of an activist than a writer. This is Arundhati-the-activist's book except for some parts few and far between where Roy's literary originality, mischief, and humor pokes its head out for the starved reader to gorge on. It's understandable that most readers were enraged when they found that the activist had hijacked the writing of this novel.

This certainly isn't a novel in its traditional sense. Roy lays a buffet of India's most important social and political issues from the plight of Hijras to Naxalism to Kashmir. Characters are mere literary formalities she has to go through to ax in what she really wants to say about those issues. Some characters thankfully escape into three dimensions from their cardboard cutouts and such escapes are the ones that make this read worthwhile. If we didn't know better, we could argue that this book experiments with the structure, pushes the boundaries and expands the very meaning of a novel. But we know that Roy's concern for India and its oppressed, faceless and voiceless people (around which she has modeled her life as an activist. A formidable thing to do.) far outweighs her concerns (if any) about the appropriateness of this book as a literary work. Should we just call it transgressive in terms of structure and leave it at that?

The novel begins beautifully with the story of Anjum and for at least the first hundred pages you feel the same sense of ecstatic helplessness you felt with the seductive prose of The God of Small Things. But everything goes for a spin as the novel progresses, burdening itself with more characters, more agenda and even more national issues like a train slowly filling itself with passengers to the point of inundation. It is hard not to feel that Roy had an exhaustive checklist of problems she wanted to cover within the confines of this novel. But the momentary flashes of brilliance keep us going. It's amazingly written and there cannot be a second opinion about that. Roy's prose almost consolingly makes up for all the other multitudinous drawbacks.

If you're the one to find autobiographical elements in fiction interesting, you have Tilottama who seems to be a partial portrait of Roy herself. It is not widely known that Roy is an architect, that she lived in Delhi slums and tried her hands in acting, screenplay writing and a lot of other odd professions before writing her debut novel. (Her performance as an actress was highly praised by Sujatha in an article for Kanayaazhiyin Kadaisi Pakkangal he wrote around 1990. And she won a national award for screenplay writing in the late 80s.) If she decides to actually write it, her autobiography would be quite fascinating.

Written over a period of twenty years, you can sense the occasional palimpsest. Malls and WhatsApp and memes feel alien in this novel's landscape. They serve no purpose other than being the designated markers of contemporaneity. Not that they have to serve any purpose. But, there's too much plastic garbage contrived into this story.

But complaints apart, every issue she talks about IS actually relevant. Every single thing she complains about is making the lives of millions miserable. The day after I read about a Hindu mob lynching a man carrying the carcass of a cow (dead of natural causes) for killing-it-to-consume-it in this novel, an eerily similar event made the national headlines. We don't have any single intellectual in India who is famous across the country, who doesn't have prejudices against the North or the South, who is liberal in his views, who has international celebrity, who actually cares for the downtrodden and dares to oppose any giant power not fearing the consequences. Arundhati Roy is the closest we have to such an icon. She doesn't stop with merely talking about these issues. She protests with and for the oppressed. She screams because we've chosen to ignore their cries for too long and because she has one of the few voices that are heard.

But stacking one issue upon another without giving much importance to the emotional quotient ironically leads us to be inured to the very issues that were supposed to draw some kind of response from us.

Some magazine called Ministry "a fascinating mess" and there's no better way to put it. Tiring, perplexing and enraging at times; it is also funny, moving, memorable and horrifying. Like most things in this world, a binary good/bad classification would fail here and we gotta accept that it's a mixed bag. In these merciless, solipsistic times it is rare to find voices bursting with concerns about fellow humans and that's exactly why this book is to be treasured, fractured and disorderly though it may be. -

This is a political book from A. Roy, reflecting on the conflict and times of turmoil between India and Pakistan over Kashmir. The multitude of intricacies; the problems the peoples of that region had to face for many decades are being told through the viewpoint of many protagonists; each fighting their own demons and telling their part of the multifaceted drama. The effects of new imperialism, exploitation of people's lands, corruption of governments, people divided by religon, effects of invasion of Afghanistan, constant war as a way of money-making is given in the stories; fragment by fragment, motif by motif, through experiences from both sides..

The story begins innocently, much like a fairy-tale from 1001 nights. But then the violence, the pain, the hate shatters this peace. In the end, all the characters gather in a graveyard (one way or another) and in/through death all is erased and equalized; all the lost pieces of the soul are buried, and innocence starts being restored for the people in the story. However one knows its hardly the end of any evil, and so there is no relief.. -

'Once you have fallen of the edge like all of us have, including our Biroo,' Anjum said, 'you will never stop falling. And as you fall, you will hold on to other falling people. The sooner you understand that the better. This place where we live, where we have made our home, is the place of falling people. Here there is no haqeeqat. Arre, even we aren't real. We don't really exist.'

These words by Anjum, the hijra (transgender in modern terminology), encapsulate what Arundhati Roy has tried to do with The Ministry of Utmost Happiness: create a narrative of the "falling people", who are always left on the margins of mainstream discourse in India. While doing that, she wants to expose India's steaming underbelly to the world - the not-so-palatable face of this up-and-coming economic and military superpower. In this, however, she fails.

In my opinion, the heart of any novel is the story: the reader has to be drawn into it, get invested in the characters, follow their careers with interest as they navigate the fictional map the author has concocted. In a political novel, this will be imbued with a heavy dose of the author's ideological viewpoint. But if she/ he has taken care in the structure of her story, the politics will remain an undercurrent and will never overwhelm the narrative (check out

Paul Scott's

Raj Quartet, 4 Vol. for an excellent example). Unfortunately, in the novel under discussion, Ms. Roy lets her obsessions (the Kashmir issue, the rise of Hindu fanaticism in India, Maoist rebels in India's Naxal belt) take over at the expense of the story. The result is a curious patchwork of different characters with disparate narratives, like a patchwork quilt.

The novel starts with Anjum, a transwoman in Delhi, moving out of her hijra residence (the "Khwabgah" - Abode of Dreams) to set up house in a Muslim graveyard, after a horrendous experience in the 2002 Gujarat riots. Slowly, she starts building a house which grows, encapsulating many graves in the process: and her house becomes a sort of refuge for the odds and ends of humanity. Chief among them are Saddam Hussein (actually a Dalit named Dayachand) and his horse Payal; the Imam Ziauddin who has been abandoned by his family; a sick beagle named Biroo; sundry hijras who visit often and (later) the enigmatic S. Tilottama and her adopted daughter the Second Miss Jebreen. The house, where impromptu funeral services are also conducted, is known as the Jannat Guest House and Funeral Parlour.

From this Marquezian premise, the story suddenly jumps to the Jantar Mantar in Delhi, where a baby is abandoned during a protest. Even though Anjum tries to claim her, she is unsuccessful. The baby is safely appropriated by Tilottama - and the novel suddenly becomes her story.

Tilottama (a thinly disguised alter-ego for the author, it seems) is a Malayali who was born illegitimately to a Syrian Christian in Kerala, and adopted by her biological mother. She ends up in Delhi, among the intelligentsia in the campuses of the eighties, and becomes part of a love quadrangle - Nagarajan Hariharan, the rebel son of an ambassador, Musa Yeswik, a Kashmiri and Biplab Dasgupta, a Bengali from a rather conventional middle-class family. But eschewing marriage altogether, Tilo drops out from view - only to surface later as a prisoner of Major Amrik Singh, a feared army man who is known as a butcher. It is suspected that she has been with Musa, who is now a militant, and has been killed in an encounter. Biplab, who is in the Intelligence Bureau by this time, saves her with the help of Naga, who has become one of the most intrepid journalists in Kashmir. Tilo subsequently marries him, only to ditch him some seventeen years later and move in as a tenant of Biplab's. She doesn't tell anyone what happened to her. We readers also learn it only towards the end, when she moves in with her baby into the Jannat Guest House: why the baby is called Miss Jebreen the Second, what exactly is the relationship between Tilo and Musa is, and what was the unspeakable tragedy that befell him.

Once they are all ensconced in Jannat Guest House, however, the narrative takes on a sedate pace and it culminates in a strangely upbeat ending.

***

Arundhati Roy is an intensely political person. She makes no secret of which side she is on: always with those she perceives as the underdogs. In Kashmir, she is with the militant who is resisting the "occupation" (official circles in India may dispute the term) by the Indian Army; in Bastar, the region overrun by armed Maoist insurgents, she is with them against the Indian State. She sees the state as the ultimate oppressor, and is the closest to an anarchist rebel among all the leftists in existence today.

That is fine. What is not is that in writing a political novel, she lets ideology take precedence over the story, with the result that we have a confusing novel with characters who are rather of the pasteboard variety. Except for Anjum and Saddam, I couldn't engage with any of them.

Things are in stark black and white. The occupying Indian Army in Kashmir is evil in the extreme, raping, killing and torturing at pleasure (they even kill dumb animals just for the heck of it). Amrik Singh is the classic Bollywood villain, and Musa is the the quintessential Scarlet Pimpernel-esque hero. As the descriptions of murder, torture and rape go on and on, it is clear on which side the author wants her readers to be.

(I have no illusions about the Indian Army [or any army for that matter]. And it is true that they are handling Kashmir in a less-than ideal way. However, in any fictional narrative, a nuanced treatment is always better.)

The structure of the novel is a mess, with multiple viewpoints zigzagging all over the place. (In between, Biplab alone talks in first person - God knows why.) The flow of narrative is purposefully broken with notes written by the characters, asides, philosophical ruminations and whatnot. Contemporary politicians come and go in wafer-thin disguises. Large sections are given over to exposition which would have been better in an essay.

Arundhati Roy writes beautiful English. That makes this book readable - but not enjoyable.

I will leave with two quotes, which seem to sum up what the author wants to say through this book. The first is from Biplab Dasgupta, as he ruminates about his home street:Compared to Kabul, or anywhere else in Afghanistan or Pakistan, or for that matter any other country in our neighbourhood (Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Burma, Iran, Iraq, Syria - Good God!) this foggy little back lane, with its everyday humdrumness, its vulgarity, its unfortunate but tolerable inequities, its donkeys and its minor cruelties, is like a small corner of paradise.

This is the middle-class Indian, far removed from the ugly things that is taking place elsewhere in his country.'One day Kashmir will make India self-destruct in the same way. You may have blinded all of us, every one of us, with your pellet guns by then. But you will still have eyes to see what you have done to us. You're not destroying us. You are constructing us. It is yourself that you are destroying...'

This is Musa the militant speaking. And reading it on the same day that I saw the picture of a nineteen-month-old baby shot in the eye with a pellet gun, these words seem to take on ominous meaning. -

The much anticipated follow up to The God of Small Things. I know opinions have been divided about this, but for me it did not disappoint. It is panoramic in scope with a vast range of characters. It ranges across the Indian subcontinent with a special focus on the conflict in Kashmir. The novel’s real focus is the marginalised, the victims of corruption, oppression and prejudice. The novel’s politics is laced with irony and humour. There is also great human warmth amidst the horror.

As always Roy’s writing is lyrical and adds lustre to the everyday. This is how the novel begins;

“At magic hour, when the sun is gone but the light has not, armies of flying foxes unhinge themselves from the Banyan trees in the old graveyard and drift across the city like smoke. When the bats leave, the crows come home. Not all the din of their homecoming fills the silence left by the sparrows that have gone missing, and the old white-backed vultures, custodians of the dead for more than a hundred million years, that have been wiped out. The vultures died of diclofenac poisoning. Diclofenac, cow aspirin, given to cattle as a muscle relaxant, to ease pain and increase the production of milk, works—worked—like nerve gas on white-backed vultures. Each chemically relaxed milk-producing cow or buffalo that died became poisoned vulture bait. As cattle turned into better dairy machines, as the city ate more ice cream, butterscotch-crunch, nutty-buddy and chocolate-chip, as it drank more mango milkshake, vultures’ necks began to droop as though they were tired and simply couldn’t stay awake. Silver beards of saliva dripped from their beaks, and one by one they tumbled off their branches, dead.”

The plot is complex and the characterization excellent and for me the standout characters were Anjum and Tilo. The plot is labyrinthine and I’m not going to try to explain it. Roy does try to explain her country:

“Normality in our part of the world is a bit like a boiled egg: its humdrum surface conceals at its heart a yolk of egregious violence. It is our constant anxiety about that violence, our memory of its past labors and our dread of its future manifestations, that lays down the rules for how a people as complex and as diverse as we continue to coexist — continue to live together, tolerate each other and, from time to time, murder one another.”

It is clear she feels passionately about the plight of those she writes about and her challenges to Hindu nationalism have made her unpopular in some quarters. Roy does see the inherent tension in her position as well as one of the characters writes.

“I would like to write one of those sophisticated stories in which even though nothing much happens there’s lots to write about. That can’t be done in Kashmir. It’s not sophisticated, what happens here. There’s too much blood for good literature.”

As Anita Fellicelli points out in her review;

“The true measure of a democracy is in how it treats its most marginalized and vulnerable people.”

Roy’s criticisms are pertinent, but in the west it feels to me like we are also guilty of the same, making her warnings just as relevant. This is one of my favourites this year. -

4 stars for the prose

2 stars for enjoyment

I’ve heard so many wonderful things about Arundhati Roy’s “ The God of Small Things” that I was really looking forward to reading her latest - despite a few less than shining reviews. I was still looking forward to reading “ The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.”

What can I say about my actual experience reading this? I was occasionally awed by her prose, lovely. This is a moving story filled with the horrors of man’s inhumanity to man, not a new topic, but not one to be complacent about. And yet, even though I read lovely, thoughtful, perhaps even inspired sections, there were very limited times when I felt anything. It felt a bit like rapidly fired information, with little or no emotional connection.

Every time I would pause, or close this book for any period of time, I would hear the same ‘refrain.’

“I felt... nothing.”

Still, I persisted... and there were moments that gave me hope, but ultimately, overall, that feeling didn’t change.

“Ev'ry day for a week we would try to

Feel the motion, feel the motion

Down the hill.

“Ev'ry day for a week we would try to

Hear the wind rush, hear the wind rush,

Feel the chill.

“And I dug right down to the bottom of my soul

To see what I had inside.

Yes, I dug right down to the bottom of my soul

And I tried, I tried.

“And everybody's goin' ‘Whooooosh, whooooosh ...

I feel the snow... I feel the cold... I feel the air.’

And Mr. Karp turns to me and he says,

‘Okay, Morales. What did you feel?’

“And I said...’Nothing,

I'm feeling nothing,’

And he says ‘Nothing

Could get a girl transferred.’

“They all felt something,

But I felt nothing

Except the feeling

That this bullshit was absurd!

“Six months later I heard that Karp had died.

And I dug right down to the bottom of my soul...

And cried.

'Cause I felt... nothing.”

-- “Nothing” – Chorus Line

Many thanks, once again, to the Public Library system for the loan of this book! -

Arundhati Roy waited 20 years to write the follow up to her Booker-prize-winning and best-selling debut novel, so unsurprisingly many publishers vied for this book. She tells in a Guardian interview how she chose the successful publisher:

She told her literary agent, “I don’t want all this bidding and vulgarity, you know.”

At first sight this is a humorous and praiseworthy anecdote, but read after reading this bloated and shambolic novel it reads very differently. I strongly suspect the unsuccessful publishers suggested cutting several of the characters (who then objected in the vote), deleting large parts of the book and splitting it into two novels. Had their advice been taken this could have been a - or two - great novels. As it is, it is a massive disappointment, and disappointing in turn that the Booker jury longlisted it on I suspect the grounds of the author's Booker legendary status, and political worthiness rather than its actual merits.

She wanted interested publishers to write her a letter instead, describing “how they understood” her book. She then convened a meeting with them. “OK,” her agent prompted afterwards. “You know what they think. You’ve met them. Now decide.”

“Oh no,” she told him. “Not yet. First I’ll have to consult.” He was puzzled. “You consult me, right?” “No, I have to consult these folks. You know, the folks in my book.” So the author and her agent sat together in silence while she asked the characters in her novel which publisher they liked the best.

(The lack of tough editing of a follow-up novel to a best-seller reminded me strongly of Donna Tartt's Goldfinch, where my review [

https://www.goodreads.com/review/edit...] began "It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a famous writer in possession of an over-long novel, must be in want of an editor.”)

One of Roy's assertions - via a character, but it is one of several places where she indirectly justifies her style is:

I would like to write one of those sophisticated stories in which even though nothing much happens there's lots to write about. That can't be done on Kashmir. It's not sophisticated, what happens here. There's too much blood for good literature.

Fortunately there is a debut novel out this weekend that proves her wrong - Preti Taneja's We That Are Young, by someone equally involved in human rights work, albeit without the headline grabbing trips to Moscow with Hollywood stars. I loved it when I read an ARC (

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2...) and great to see it get a rave review in The Sunday Times today:

thetim.es/2waJwdF.

Please read that instead and skip this one.

----------------------------------------------------

A few comments on the book :

Arundhati Roy has spent the last 20 years engaged in a wide variety of human rights and political campaigning. Perhaps unsurprisingly she attempts to cram pretty much every one of those themes into this novel. More disappointingly though she includes a number of characters based on curde caricatures of real-life people.

The Prime Ministers (Manmohan Singh as the "trapped rabbit", Modi as "Gujarat ka Lall") are obvious to the reader and arguably fair game, if rather easy targets.

But, for example, it took me a while and some googling to get that Mr Aggrawal is based on Arvind Kejriwal and Anna Hazare is the real-life tubby Ghandian. And frankly their inclusion comes across as rather petty score settling on Roy's behalf given they were originally all on the same side in the anti-corruption protest before splitting in Judean People's Front fashion. To be fair to Roy, in another place where she has her characters apologise for the faults of her novel (see above also) she has one of her characters tell a version of Emo Philip's wonderful and related joke (

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/200...). But acknowledging a novel's flaw doesn't make them go away.

To try some praise though she is particularly strong, in polemic if not, by her own admission (above) novelistic terms, on the situation in Kashmir. And also on the worrying distortion of democracy in India with an increasing tyranny of the majority: a theme that also underlies Brexit (tyranny-of-the-52%), Trump (albeit the tyranny of a-minority-except-under-an-archaic-electoral-system) and in the U.K. McDonnell (the as yet unfilled desire for a tyranny-of-the-losers).

Salman Rushdie expressed this well in the Guardian in an article on the 70th anniversary of partition (

https://www.theguardian.com/books/201...)Midnight’s Children was published a few months before the 34th anniversary of Indian independence in 1981, and another 36 years have elapsed since then. The novel now feels like a half-time report. The second half deserves its own novel, although I am not the right person to write it.

I also enjoyed the novel's two main characters.

There is no sign that the Indian electorate will turn against the present government any time soon. Midnight’s grandchildren seem content with what’s happening. And that’s the pessimistic conclusion to volume two of the Indian story.

- Tilo, who could be taken as a proxy for Roy herself: certainly Tilo's mother's life (albeit not her death) is closely based on that of Roy's own (Mary Roy), as was Ammu in God of Small Things: but Roy herself has observed in interviews:Tilo, Tilottama, is the fictional child of Ammu and Velutha in The God of Small Things, had their story ended differently. She’s the younger sibling of Esthappen and Rahel. So, you know, I know her well, but I’m not her.

- and Anjum, a 'hijra', who in the novel's opening chapters again provides a justification of Roy's technique:

Long ago a man who knew English told her that her name written backwards (in English) spelled Majnu. In the English version of the story of Laila and Majnu, he said, Majnu was called Romeo and Laila was Juliet. She found that hilarious. “You mean I’ve made a khichdi of their story?” she asked. “What will they do when they find that Laila may actually be Majnu and Romi was really Juli?” The next time he saw her, the Man Who Knew English said he’d made a mistake. Her name spelled backwards would be Mujna, which wasn’t a name and meant nothing at all. To this she said, “It doesn’t matter. I’m all of them, I’m Romi and Juli, I’m Laila and Majnu. And Mujna, why not? Who says my name is Anjum? I’m not Anjum, I’m Anjuman.

I’m a mehfil, I’m a gathering. Of everybody and nobody, of everything and nothing. Is there anyone else you would like to invite? Everyone’s invited.

If I may for once use the Bible as literature rather than scripture, one is tempted to respond that "many are invited but few are chosen", or at least that is the way an author and editor should approach a novel. -

I am not going to give this 5 stars because it did not totally win me over the way

The God of Small Things did. However it was still a very satisfactory reading experience.

I must say first though that there is a lot about politics and politics do not interest me one tiny bit as much as they do

Arundhati Roy. So I have to admit to the teeniest amount of skimming from time to time. Which is a shame because she writes so very beautifully at all times. I have not been to India but she makes me feel as though I know it well with her beautiful descriptions.

There is a small army of characters, some with difficult names, but the important ones are drawn well and their lives are quite extraordinary. Our main character, Anjum, ends up building a guest house in a cemetery with rooms built around graves. Definitely original.

This is a book from which we can learn a lot about India, about war and poverty and what it does to people and of course how these people still live and love and survive. Definitely worth reading! -

I'm giving up on this one. It has flashes of her brilliance, but it wanders too far and too often from the path.

-

This year's Man Booker longlist announcement is due in a couple of days, so now seemed a good time to catch up with the only one I missed from last year's list. I was deterred by the high price of the hardback edition and some pretty negative friend reviews, which lowered my expectations to the point where I was pleasantly surprised by how much I enjoyed it.

As Roy's first novel in 20 years it is hardly surprising that it has a lot of ground to cover. So yes, it is a little messy and perhaps unfocused, but she has an instinctive sympathy for India's many and diverse outsiders (hermaphrodites, Kashmiri Muslims, untouchables and unmarried mothers are among its array of unlikely characters). There is plenty of humour mixed with the darker stories, and I was reminded a little of early Rushdie, particularly

Shame.

It is now a little late to talk of where I would rank this in last year's longlist and some of them have faded from memory a little, but I would say 7th or 8th, and only as low as that because there were so many books I loved on that list, and in weaker years it might well have deserved a shortlisting.