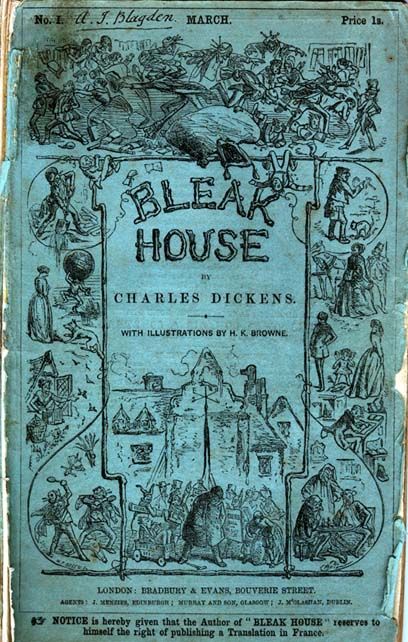

| Title | : | Bleak House |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0143037617 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780143037613 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 1017 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1853 |

Bleak House Reviews

-

Okay, so this is the 1853 version of The Wire. But with less gay sex. And no swearing. And very few mentions of drugs. And only one black person, I think, maybe not even one. And of course it's in London, not Baltimore. But other than that, it's the same.

Pound for pound, this is Dickens' best novel, and of course, that is saying a great deal. I've nearly read all of them so you may take my word. Have I ever written a review which was anything less than 101% reliable, honest and straightforward? Well, there you are then.

Bleak House gives some people a leetle problem insofar as you have half of it narrated by Esther (Goody Three Shoes, too good for just two) Summerson, who you ache to have a few bad things happen to, because she trills, she sings, she sees the best in everyone, tra la la, tweedly dee dee. This does get on some people's nerves. But I downloaded a dvd called Dickens Girls Gone Wild last week and let me tell you there's a whole other side to Esther Summerson - given the right surroundings (I think it was Malta, and the sangria was flowing) she could be good company.

However. Bleak House as a whole does no more than take it upon itself to explain how society works. And it's utterly gobsmacking. There are a lot of words in Bleak House's 890 pages but gobsmacking is not one of them. It's a word that was invented to describe Dickens novels. -

This is a very clever book because the main issue with it is exactly the point Dickens is making: it is so long and dragged out.

Bleak House is quite the achievement. It's a 900+ page monster made up a thousand different subplots with a large cast of characters. It also fanned the flames that led to a

huge overhaul of the legal system in England. Buried beneath and entwined with the many subplots is the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce - Dickens's parody of the Chancery Court system (because the case is dragged out over many years).

I like Dickens, and I can appreciate what

Bleak House does, but I'm sorry to say I won't be joining the ranks who consider this their favourite. His best work objectively? Maybe. Who even knows what that means? But definitely not my favourite. That would be

Great Expectations-- a novel that just rips my heart out and stomps all over it.

I really do understand that this is the whole point, but so many chapters and events in this book were extended needlessly, padded out with waffle and meanderings that seemed to have nothing to do with the novel at large. That's very clever and all - given that this is a critique of a court system that extends everything needlessly and gets nothing done - but it's a bit of a chore to read. It's a shorter book than

Les Misérables,

The Count of Monte Cristo and

War and Peace, but it truly doesn't feel like it.

The characters, too, were not as memorable as many of Dickens others. Having read it, I can now see why the

Bleak House characters are not household names like Miss Havisham or Bill Sykes. I found them bland in comparison. I also think it was a mistake to have the simpering "I'm so modest and unintelligent" Esther Summerson as a narrator (Dickens's only female narrator). It's unfortunate because I think Dickens usually excels at first person narration, but Esther's constant need to reiterate her modesty and lack of intelligence is frustrating.

If I were rating this book based on how well it achieved what it set out to do, it would be an easy five stars. If you believe classics are not there for enjoyment but for self-flagellation, this is an easy five stars. Dickens successfully wrote a long and slow book to show how the legal system is so long and slow. Some of the subplots and character dramas were interesting; many were not.

Blog |

Facebook |

Twitter |

Instagram |

Youtube -

Shivering in unheated gaslit quarters (Mrs. Winklebottom, my plump and inquisitive landlady, treats the heat as very dear, and my radiator, which clanks and hisses like the chained ghost of a boa constrictor when it is active, had not yet commenced this stern and snowy morning), I threw down the volume I had been endeavoring to study; certainly I am not clever, neither am I intrepid nor duly digligent, as after several pages I found the cramped and tiny print an intolerable strain on my strabismic eyes. Straightening my bonnet, I passed outdoors into the frigid, sooty streets, where shoppers bustled by in a frenzy, now rushing into the 99-cent store, bedecked with PVC Santa Claus banners, now into Nelson's Xmas Shoppe, in search of glistening ornaments. Bowing my head perversely against busy crowds and fierce wind, I stepped into a subway, which conveyed me to a winding street down which I hurried until I reached a peculiar establishment, the shingle for which had been battered by the strain of city winters, by pollution, and no doubt by the small mischievious hands of vandals, who had modified the sign with their colorful signatures and illustrations, but upon which could still be read - with some effort - Amperthump & Hagglestern, Booksellers.

I entered to a sound of tinkling bells affixed to the heavy door, the hinges of which creaked as I propelled myself through its narrow passage. Proceeding forward, I heard a sullen voice squeak, "Check yer bag, miss?" and glanced up to see an urchin, nearly lost amidst piles of remaindered volumes, beckoning with one grubby hand while clutching a wrinkled comic in the other; I refused, smiling gently, and passed into the densely cluttered shop, where I was intercepted by Mr. Amperthump, the proprietor, a gentleman of about three and forty, whose thick-rimmed spectacles and corpulent physique recall two of a tragic trinity of dead singers, who upon seeing me took my cold hands in his ink-stained ones and kissed them. "How can I assist, my dear?" he boomed so loudly that a little one-eyed spaniel started from its slumber, and the urchins shelving books glared up at their master with undisguised annoyance.

Drawing out my small copy of Bleak House, which I had obtained from the Queens Public Library -- supported, to wonderous effect, by the subsciption of tax dollars, and no doubt supplemented by charitable impulses of certain gentleladies -- and endeavored to explain, as simply as I could, that I desired an edition of the same narrative writ larger and in more mercifully legible print. However Mr. Amperthump appeared distressed and could not remain silent long, flinging my book away. "NO!" he cried. "You are too young and pretty" (at this I blushed and tried to protest, for I am not pretty, in fact I am plain) "to be reading this antiquated rot! Here, instead, is the latest experimental fiction from Rajistan D. McGingerloop." At this he placed in my hands a queer volume, unlike any I had seen before. "Throughout his controversial career McGingerloop has exploded one by one conventions of the novel... in this latest work he has done away with pages!" And indeed, when I examined the book I discovered he was quite right, and that the book I held was a brick of paper, and could not be opened, having as he indicated, no pages at all. I thanked Mr. Amperthump for his solicitude, at which point he pressed that I try Petunia al Gonzalez-Mjobebe's story of a love affair between an Iranian transexual and a Chinese android, a meditation, Mr. Amperthump assured me, on globalization and identity, but also, he said, a suspenseful legal thriller in its own right, albeit one subverting the conventions of that genre - quite, he added, subversively. Finally I was given to understand that in addition to Mr. Amperthump's conviction that I should not be reading Dickens, he had none in stock, and finally I gave my thanks for all his kindness and passed out again into the filthy snow and gloom. -

Which house in Charles Dickens's novel is "Bleak House"?

It surely cannot be the house which bears its name; a large airy house, which we first visit in the company of the young wards of Jarndyce, Ada Clare and Richard Carstone, and their companion Esther. Ironically, this "Bleak House" is anything but bleak. It is a pleasant place of light and laughter. Mr. Jarndyce imprints his positive outlook on life, never allowing the lawsuit to have any negative influence. Indeed, when he first took on the house from a relative, Tom Jarndyce, he says,

"the place [had become] dilapidated, the wing whistled through the cracked walls, the rain fell through the broken roof, the weeds choked the passage to the rotting door. When I brought what remained of him home here, the brains seemed to me to have been blown out of the house too; it was so shattered and ruined.”

Neither can it be another house, which is to bear its name far later in the novel. So does the title perhaps refer to "Tom-All-Alone's", originally owned by Tom Jarndyce, but now a decrepit edifice inhabited by poor unfortunates who have nowhere else to go, sleeping crammed on top of each other? Tom-All-Alone's certainly represents the worst of society's injustices. Or could it be the immensely grand, laybrinthine mansion, "Chesney Wold", owned by Lord and Lady Dedlock? That is a magnificent abode, complete with its ominously suggestive "Ghost Walk"; much admired, much respected, but devoid of happiness. It embodies a bleakness of spirit; those living in it live a lie, and mourn the past. Or is it more likely to be one of the smaller neglected dwellings, such as that of Krook the rag-and-bone merchant, whose house is packed to the brim with junk and paper - or his neighbour, the mad Miss Flite, herself once a ward of Jarndyce, now reduced to living with her caged birds,

"Hope, Joy, Youth, Peace, Rest, Life, Dust, Ashes, Waste, Want, Ruin, Despair, Madness, Death, Cunning, Folly, Words, Wigs, Rags, Sheepskin, Plunder, Precedent, Jargon, Gammon, and Spinach."

Or the house inhabited by Mrs Jellyby; yet another neglected house near to falling down, as she furthers her missionary zeal, leaving her daughter Caddy to cope as best she can with the crumbling household? Her self-righteous friend Mrs. Pardiggle's house, is also a candidate,

"The room, which was strewn with papers and nearly filled by a great writing-table covered with similar litter, was, I must say, not only very untidy but very dirty. We were obliged to take notice of that with our sense of sight, even while, with our sense of hearing, we followed the poor child who had tumbled downstairs: I think into the back kitchen, where somebody seemed to stifle him."

And the hovel lived in by Jenny and her brickmaker husband, is surely a contender; that meagre hut visited with an ostentatious show of charity by the abominable Mrs. Pardiggle with her "rapacious benevolence (if I may use the expression)"? There is no shortage of candidates for a "Bleak House" in this behemoth novel - but it is by far from clear which house is meant.

Dickens has given us a surprisingly short title, but it is as well disguised as the sixty-two word long title for the novel we now call, "The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit" or even simply, "Martin Chuzzlewit..." in which throughout the novel we think it is called after one character, but on consideration, it is more likely to be about another. Dickens loved his mysteries, and this is his greatest completed mystery novel. Even the characters are in disguise. One has called himself "Nemo" - "no-one" - and another has taken great pains to obfuscate her history; yet another has never known his own name. In some cases the disguise is not by intention; one of the main characters genuinely does not know who she actually is, and thinks she is someone else.

But before this review becomes as baffling as some of the nascent strands in this novel (never fear, with Dickens everything is tied up nicely by the end), perhaps I should set the scene properly.

Bleak House was Charles Dickens's ninth novel, written when he was between 40 and 41 years of age. Whilst writing it Dickens's wife Kate gave birth to their tenth child, Edward, or "Plorn". A few months later Dickens himself went on tour throughout England with his amateur acting troupe. He then became seriously ill with a recurrence of a childhood kidney complaint, and was bedridden for six days, but still had 17 chapters to write. He went to Boulogne, France to recover, and celebrated finishing Bleak House by holding a banquet in Boulogne, for his publishers Bradbury and Evans, his close friend, the writer Wilkie Collins, and several others.

Each part of the serial was illustrated by his favourite illustrator and great friend Hablot Knight Brown, or "Phiz", with remarkable skill. His illustrations take great care to convey the dark brooding mood of the novel, or the quirkiness of the characters. They even cleverly manage to convey the novel's theme of disguise. Esther's face, for instance, is rarely shown. She is usually turned away from the viewer's eye.

This novel is often considered Dickens's finest work although it is not by any means his most popular. His working title for Bleak House was actually "Tom-All-Alone's", which seems to indicate that of all the many themes in this book, the paramount one in his mind was his hatred of the London slums. Dickens loathed both the despicable conditions there, and the governmental practices which allowed them to exist. He tirelessly campaigned for their improvement. But the action itself is intended to illustrate the evils caused by long, drawn-out suits in the Courts of Chancery. Much of it was based on fact, as Dickens had observed the inner workings of the courts as a reporter in his youth. In Bleak House he observes bitterly,

"The one great principle of the English law is to make business for itself. There is no other principle distinctly, certainly, and consistently maintained through all its narrow turnings. Viewed by this light it becomes a coherent scheme and not the monstrous maze the laity are apt to think it. Let them but once clearly perceive that its grand principle is to make business for itself at their expense, and surely they will cease to grumble."

This, then, is the crux of the story, but it is wrapped in a magnificently complex tale of mystery and intrigue. In fact there are about five major stories all interwoven in Bleak House, and it would be difficult to say which the main story is. Each is connected to the case of Jarndyce versus Jarndyce, and the destructive ramifications of two conflicting and contesting wills echo down the generations, and across all strata of society. It is a breathtaking accomplishment to plot, develop and tell such a complex story in such a riveting way. For it has to be borne in mind that this, like his preceding novels, was only accessible to Dickens's readers in small chunks of three or four chapters at a time, once a month, stretched over a year and a half: March 1852 to September 1853.

Yet his readers were gripped, entranced, demanding; able to remember the myriads of characters from one episode to the next. Perhaps this is why Dickens gave his characters such memorable tags: Jo, the crossing-sweeper, who "don't know nothink", subject to grinding poverty and ignorance, forever being "moved on"; the languid "My Lady" Dedlock, fashionably fatigued, forever full of ennui and "bored with life, bored with myself", Miss Flite, who "expects a judgment shortly", John Jarndyce, to be avoided if "the wind is in the east" and he is in his "growlery", Harold Skimpole, protesting he is "but a child" in matters of money.

The Smallweeds are a grotesque family of caricatures. The miserly money-lender Grandfather Smallweed is a very old man confined to a chair, where he is probably sitting on a large sum of money. His wife is living in fear of him, and permanently panicked by any mention of money. She starts up and talks nonsense until Grandfather Smallweed throws his cushion at her, silencing her but reducing himself to a bundle of clothes, whereupon we get his catchphrase, "Shake me up, Judy!" There is the lawyer Tulkinghorn; the man of secrets, "a great reservoir of confidences", or the lesser lawyer Vholes, the "evil genius". There are many short quips such as these, carefully planted by Dickens, to jog our memories should we need them.

Perhaps the easiest story to follow is that of Esther Summerson, a nobody whose "mother was her disgrace". She was a poor child, with a sense of being guilty for having been born, feeling that her birthday "was the most melancholy ... in the whole year". She was offered an education and a home by the benefactor John Jarndyce. Dickens invites us to view her story as key, by alterating passages of the novel, making some chapters by an omisicient narrator, and some by Esther. Unfortunately for a modern audience, we quickly lose sympathy with Esther, who seems to protest her gaucheness and ineptitude rather too much. Perhaps after all it is telling that she is Dickens's only female narrator.

In the narrative she makes it very clear how unworthy she is, how unattractive and dull compared with her peers. She also makes it abundantly clear that anyone reading her words knows that everyone in Bleak House argues with her about this, always complimenting her kindness, virtue, wisdom, hard work and her strong sense of gratitude and duty. It is tempting to view this as an ironic depiction of Esther, were we not now to know that a modest, self-effacing woman such as this, was what Dickens himself admired - or at least professed in public to admire. The character of Esther was thought to be based on Georgina Hogarth, his wife's youngest sister, who had joined his household in 1845, and was taking over more and more of the running of the house. She was apparently a self-sacrificing sort of person, who immersed herself in household duties and was dedicated to the welfare of others.

Many other characters in Bleak House were also, as was so often the case, based on people Dickens knew, and sometimes they were famous with his readers too. For instance Harold Skimpole, that dissembling, conniving hypocrite, lover of Art, Music, culture and everything that was fine and tasteful, was a thinly veiled portrait of Leigh Hunt, an English critic, essayist, poet, and writer, who continually sponged off his friends, Shelley and Byron. Dickens himself admitted this,

"I suppose he is the most exact portrait that was ever painted in words! ... It is an absolute reproduction of a real man".

Mrs. Jellyby was based on Caroline Chisholm, who had started out as an evangelical philanthropist in Sydney, Australia, and then moved to England in 1846. Over the next six years Caroline assisted 11,000 people to settle in Australia. Dickens admired her greatly, and supported her schemes to assist the poor who wished to emigrate. However, he was appalled by how unkempt her own children were, and by the general neglect he saw in her household, hence his portrayal of Mrs. Jellyby.

Another character, Laurence Boythorn, who was continually at odds with Sir Leicester Dedlock over land rights, was based on Dickens's friend, Walter Savage Landor. He also was an English writer and poet; critically acclaimed but not very popular. His headstrong nature, hot-headed temperament, and complete contempt for authority, landed him in a great deal of trouble over the years. His writing was often libellous, and he was repeatedly involved in legal disputes with his neighbours. And yet Landor was described as, "the kindest and gentlest of men".

Perhaps the most poignant character is Jo the crossing sweeper. He has, "No father, no mother, no friends", yet is essential to the plot, and clearly has a lot of innate intelligence. Perhaps Dickens took especial care with this portrayal, as according to Dickens's sixth son, Alfred, Jo was based on a small boy, a crossing sweeper outside Dickens's own house. Dickens took a great interest in the lad, gave him his meals and sent him to school at night. When he reached the age of seventeen, Dickens fitted him out and paid his passage to the colony of New South Wales, where he did very well, writing back to his benefactor three years later.

If Jo is the character likeliest to tug at the heartstrings, Inspector Bucket may be the one to admire most; the one who seems before his time, presaging much of the detective fiction we enjoy today. The character of the astute Inspector Bucket, uncomfortable unless he gives "Sir Leicester Dedlock - Baronet", his full title every time, is the first ever portrayal of a detective in English fiction, as he,

"stands there with his attentive face, and his hat and stick in his hands, and his hands behind him, a composed and quiet listener. He is a stoutly built, steady-looking, sharp-eyed man in black, of about the middle-age...there is nothing remarkable about him at first sight but his ghostly manner of appearing".

Dickens based him on the real-life Inspector Charles Frederick Field, about whom he had already written three articles in "Household Words".

Lady Dedlock's maid, Mademoiselle Hortense, is one of Dickens's most powerful females; a prototype of Madame Defarge in "A Tale of Two Cities", full of passion, outrage, and talk of blood. She was modelled on a real-life Swiss lady's maid, Maria Manning, who, along with her husband were convicted of the murder of Maria's lover, Patrick O'Connor, in a case which became known as "The Bermondsey Horror." All Dickens's contemporary readers would have been familiar with the case.

Amusingly, one character is named after a real person - though she is not a human being at all but a cat! Krook's cat "Lady Jane", is named after Lady Jane Grey who reigned as Queen of England for a mere nine days in 1533. (She was forced to abdicate, imprisoned, and eventually beheaded.)

Although the theme of greed and corruption within the law is bitingly serious, and a passionately held belief by Dickens, and although the mysteries pile one on top of another throughout the book, Dickens provides plenty of comic characters to lighten the mood and pepper his stories. As well as those mentioned, there is the twittery Volumnia Dedlock, a poor relation of Sir Leicester Dedlock, described as "a young lady (of sixty)...rouged and necklaced". And we have the junior lawyer Mr. Guppy, almost too clever for his own good, presented in a ridiculous light, although actually having a sound and loyal moral core. He is one of my personal favourites.

There is also Mr. Turveydrop, the owner of a dance academy, and a "model of deportment ... He was pinched in, and swelled out, and got up, and strapped down, as much as he could possibly bear." Esther comments, "As he bowed to me in that tight state, I almost believe I saw creases come into the whites of his eyes." His hardworking, dancing master son "Prince" (named after the Prince Regent) is another humorous portrayal, as is Caddy Jellyby. Albeit a drudge and slave for her philanthropic mother, we are first intoduced to Caddy as a comical crosspatch with inky fingers. The tiny tot Peepy Jellyby is a delight, and Caddy's father too, is almost pathetically comical, finding consolation in leaning his head on walls; any wall seeming to suffice.

We do get a slightly different view of the other characters through Esther's eyes, which makes for interesting reading. Harold Skimpole, for instance is, I think, only shown within her purview. But with the comic episodes it matters not whose eyes we are viewing them through; we just enjoy their exuberance as a contrast to the simpering sentiments of Esther, "Dame Durden", "Old Woman", "Little Woman", "Mrs. Shipton" "Mother Hubbard", or any of the other appellations coined by the inhabitants of Bleak House. She herself is irritatingly wont to call Ada "my dear", "my darling", "my pet", or "my love", rarely using her actual name, even in reported speech. My, how tastes do change.

So which house do I personally think "Bleak House" refers to? It could well be Chesney Wold, which by the end has itself become a kind of tomb for the ghosts,

"no flag flying now by day, no rows of lights sparkling by night; with no family to come and go, no visitors to be the souls of pale cold shapes of rooms, no stir of life about it",

But given all the metaphors in the novel, I am bound to conside the title itself as a metaphor.

In most of his works, Dickens imbues buildings, particuarly old houses, with their own personality. Each become a character in its own right. Bleak House, in my view, is a metaphor for the High Court of Chancery.

So would it be too fanciful of me to suggest that the main character in this novel in the Law itself? Read it and see what you think. You don't need to take 18 months, as Dickens's public had to. But it may be a good idea to not race through this book, if you want to follow all the mysteries. Perhaps you may wish to explore the contrasting themes of antiquity and tradition represented by Sir Leicester Dedlock, set against the ever encroaching Industrial Age; an age of progress, represented by the housekeeper's grandson, the iron-master's son, Watt (such an appropriate first name!) Rouncewell. Or perhaps the theme of being trapped, being a prisoner, being caged calls to you. There are a host of examples within. Or the theme of unhappy families; bad child-rearing is shown time and time again in all its many guises, with equally devastating effects for rich and poor alike. Nearly all the lives of these characters seem to be unfulfilled, and have been blighted by coincidences or misunderstandings. They are people trapped by their circumstances.

You may find that you enjoy spotting the codes, or the continuing motifs of paper, birds, disguised faces, fire, and so on; not to mention getting the most out of Bleak House's masterly complexity and thrilling atmosphere. You may love the richness of the language and description. Or you may, in the end, become addicted to the mystery element and read it strictly for the story itself. There are many interwoven plots in this novel and altogether there are ten deaths as it proceeds; all of them tragic in different ways, and most of them key characters. One is due to a hot topic in scientific debate, so contentious that Dickens felt the need to defend it in his preface. In February 1853, just over halfway through this novel, he became involved in a public controversy about the issue of . George Henry Lewes had argued that the phenomenon was a scientific impossibility, but Dickens maintained that it could happen.

I do not tell the story, it would be well nigh impossible anyway in this space, but I do encourage you to read this masterpiece.

A labyrinth of grandeur...an old family of echoings and thunderings which start out of their hundred graves at every sound and go resounding through the building. A waste of unused passages and staircases in which to drop a comb upon a bedroom floor at night is to send a stealthy footfall on an errand through the house. A place where few people care to go about alone, where a maid screams if an ash drops from the fire, takes to crying at all times and seasons, becomes the victim of a low disorder of the spirits, and gives warning and departs. -

Is a lawsuit justice, when it goes on and on ....and on, seemingly in perpetuity ? In Bleak House located in the countryside outside of London, that is the center of the story, years pass too many to count, the lawyers are happy the employed judges likewise ; the litigants not... money is sucked dry from their bodies...like vampires whose fangs are biting hard, the flesh weakens and the victims blood flows , ( cash ) evaporates and soon nothing is left but the corpses... the gorged lawyers are full until the next too trusting suckers walk by . In the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce the quite unimportant truth be told, little known except to those who are very sadly

involved in the Court of Chancery, notorious well renowned for its slow pace ZZZ... The court clerks, audiences or should I say spectators, and even the attorneys are amused, laughter frequently heard, not a surprise this British institution no longer exists... Esther Summerson is a typical orphan in another Charles Dickens book raised by a cold woman, (and others previously of the same type) that calls herself the child's godmother, Miss Barbary, with a mysterious background too somehow connected to the young girl but how... Often telling the unloved Esther it would have been better for all , if she had never lived. Nevertheless this enigma which the few people in contact with Summerson, maybe that name is really hers , none will discuss with the teenager. The unfriendly lady keeps the puzzle a puzzle, from the past... she won't reveal who the Miss is, the old woman Barbary can keep a dark secret. Sent to a girls boarding school later, Esther bills are paid by an extraordinary kindly gentleman John Jarndyce, yes the man unwillingly entangled in the detestable lawsuit ( like many others) started by his uncle, ironically deceased still he inherited the case. Soon the courts give custody to him his two distant cousins, orphans, there are many in Victorian England, set circa the 1830's before the railroads made travel easy. Richard Carstone an amiable but lazy boy and the beautiful loyal Ada Clare, they are also distant relatives. Bleak House Mr. Jarndyce home is not empty any more, to this rather gloomy place arrives another ward of the court Esther, their guardian is the bright spot, strangely she has somehow a relationship to the suit also. The three become quick friends all around 17. Richard and Ada fall in love, Esther is their best friend. Sir Leicester Dedlock, the arrogant Baronet (get the symbolism) is a party in the suit, his haughty wife Honoria, pretty and intimidating but there is something not quite clear there. The family lawyer Mr. Tulkinghorn, has unseen power over the proud aristocrats, he is a very capable man yet somewhat soft spoken and very quiet for his noisy profession...

...but what is it ? And the Inspector Mr. Bucket of the London police he never seems to sleep... hovering over everyone, especially the notorious underworld criminals of

the entire city, solving crimes...One of Dickens best novels and I've read ten so far..The opening scene a description of London's famous bad weather is priceless, nobody could have done it better... -

Bleak House by

Charles Dickens

Bleak House is considered Dicken's best work. But this book was too tough for me. There are so many characters in this story. Somewhere I lost the track of the characters. However, if you give this book more time and patience to read all the details and keep track of the characters, you'll probably enjoy this. Regretfully, I didn't have enough patience to give this book more time.

And I am bored to death with it. Bored to death with this place, bored to death with my life, bored to death with myself.

Decent. -

Bleak House. How can it be over? I hold this incredible book in my hand and can’t believe I have finished it. The 965 page, 2 inch thick, tiny-typed tome may seem a bit intimidating. Relax, you can read it in a day - that is, if you read one page per minute for 16 hours. And you might just find yourself doing that.

Bleak House is more Twilight Zone than Masterpiece Theatre. However there is enough spirit of both to satisfy everyone. And indeed it should - it has it all - unforgettable characters, intrigue, plot within plot, ruined love, enormous themes, complications, and description - and what description! it goes so far, a lesser writer would be lost forever trying to find their way back. Above all, it has that brilliant, constant satirical voice of Dickens. That is the thing lost in TV, film and radio adaptations of his work. One merely gets a hint of it in the best of these.

The plot, the characters, the very fog that we encounter in the introduction, are all connected to one main thread: a lawsuit, the Jarndyce and Jarndyce case. It involves an inheritance with several wills, and it cannot be decided which one is legitimate. The case is before the Courts of Chancery and has dragged on for generations.

Someone stands to gain a lot of money and property, but the long entanglement of the law has made it a curse. While greed and madness consume certain characters (sometimes literally), there are also those who know how pointless and destructive it is to live under such hope.

Bleak House is another reminder what an important influence Dickens was on Dostoyevsky, who understood his power very well.

Bleak House is alternatively narrated by the orphan Esther Summerson, and an omniscient third person. Dickens's sophisticated juggling of narrative invents a style that really can't be defined, just like the novel itself. Is it a thriller, a romance, magic realism, a murder mystery? Yes and no. Is it a treatise on poverty, domestic violence, false charity, obsession? Again, yes and no. All is mixed into the fog - along with that forty foot long Megalosaurus that Dickens summons in the opening paragraph – and emerges as one of the best novels ever written.

-

Charles, tenemos que hablar.

Fue un poco por presión social que me acerque a ti, deslumbrado por tu fama de gran escritor. Al principio todo parecía ir bien, eras ameno, ingenioso, tenías tu pizquita de sarcasmo... pero yo necesito algo más, Charles.

No eres tú, soy yo. No quiero lo mismo que tú y terminaremos haciéndonos daño. Mejor nos damos unos años, o lustros o decenios, lo que haga falta, para pensar lo nuestro, sin prisas, sin ataduras, leyendo a otros autores, escribiendo para otros lectores, y quizás llegue ese día en que recordemos con cariño todos estos momentos que hemos pasado juntos.

Lo intenté, Charles, bien lo sabes, empecé la relación con Grandes esperanzas y hasta me dejé llevar hasta esta tu Casa desolada. 900 páginas de casa, Charles. Pero me puede tu moralismo, tu maniqueísmo simplista, la gran desconfianza que como lector siempre me has tenido: te pasas de explícito, Charles, subrayas todo tres veces y, de verdad, no hace falta, eres lo suficientemente claro la primera vez que dices las cosas.

Tú no me necesitas, siempre has sido muy tuyo, muy transparente, quizás demasiado. En estas relaciones nunca viene mal un poco de misterio y a ti se te ve a la legua, Charles, a ti y a todos tus amigotes, tan de una pieza la mayoría de ellos. Y no es que no me haya divertido esa visión infantil del talludito simplicísimus Skimpole (con lo que siempre hay de transgresor en esas criaturas cándidas), o la mirada siempre presta a turbarse con la menor corriente de aire, sobre todo si es de levante, del depresivo Jarndyce, con la perspectiva aristocrática del rentista-no-he-dado-un-palo-al-agua-en-mi-vida Dedlock que aguanta con resignación y paternalismo a esos seres de especies claramente inferiores nacidos para servirle, o la moralísima y controladora pata Pardiggle y sus horrorosos patitos… En fin, para qué seguir, no es solo diversión lo que busco, Charles.

Te mereces a alguien mejor que yo, alguien que desee dar el siguiente paso hacia otro de tus libros, yo me veo incapaz. Estoy seguro de que te irá bien, tú te lo mereces todo. Adiós, Charles. -

Bleak House, Charles Dickens

Bleak House is a nineteenth century novel by English author Charles Dickens, first published as a serial between March 1852 and September 1853.

The novel has many characters and several sub-plots, and the story is told partly by the novel's heroine, Esther Summerson, and partly by an omniscient narrator.

At the center of Bleak House is a long-running legal case, Jarndyce and Jarndyce, which came about because someone wrote several conflicting wills.

Dickens uses this case to satirise the English judicial system. Though the legal profession criticized Dickens' satire as exaggerated, this novel helped support a judicial reform movement, which culminated in the enactment of legal reform in the 1870's.

عنوانهای چاپ شده در ایران: «خانه قانون زده (بلیک هاوس)»؛ «خانهٔ متروک»؛ «خانه غمزده»؛ نویسنده چارلز دیکنز؛ تاریخ نخستین خوانش: روز هجدهم ماه فوریه سال1970میلادی

عنوان: خانه قانون زده (بلیک هاوس)؛ نویسنده: چارلز دیکنز؛ مترجم ابراهیم یونسی؛ مشخصات نشر تهران، امیرکبیر، سال1345؛ در هجده و891ص؛ چاپ دوم سال1356؛ در907ص؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، سحر، در1368، دو جلد در942ص؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، نگاه، سال1387؛ شابک9789643515256؛ در941ص؛ موضوع داستانهای نویسندگان بریتانیا - سده 19م

عنوان: خانه قانون زده (کوتاه شده)؛ نویسنده: چارلز دیکنز؛ مترجم: بابک تختی؛ تهران، دبیر، سال1395، در88ص؛ شابک9786005955941؛

عنوان: خانه قانون زده (کوتاه شده)؛ نویسنده چارلز دیکنز؛ مترجم: نیلوفر زارع؛ تهران، کیان افراز، سال1396، در58ص؛ شابک9786008854340؛

خانهٔ متروک، یا «خانه غمزده (خانه قانون زده)»، نهمین رمان «چارلز دیکنز» است، که در سال1853میلادی نگاشته شده است؛ این داستان زندگی غم انگیز طبقه ی کارگر فقیر «انگلستان» را، نشان میدهد؛ «خانه غمزده» نخستین بار، بصورت داستان دنباله دار، از روز اول ماه مارس سال1852میلادی، تا روز بیستم ماه سپتامبر سال1853میلادی، در هفته نامه ای چاپ شد؛ در رمان «خانه قانون زده»، «بازرس باکت» ماجرای قتل وکیلی به نام «تاکینگ هورن» را، رمزگشایی میکند، که در دفترش به قتل رسیده است؛ او هم مانند کارآگاه «دوپن»، در داستانهای «ادگار آلن پو»، خود را عقل کل میداند، و گرچه آدم متواضعی به نظر میرسد، اما در ماجرای بازجویی از «کنت ددلاک»، کمی از خود راضی، نشان میدهد؛ با اینحال، «باکت» کارآگاه خیلی باهوشی نیست، و حل معمای داستان، بیشتر به علت شناخت او، از محلات «لندن» ناشی میشود؛ در حقیقت به رغم اینکه «بازرس فیلد» در پژوهشهای خود، خیلی قرص و محکم جلو میرود، اما در رمان «خانه قانون زده»، «لیدی ددلاک»، از چنگ «بازرس باکت» میگریزد؛ با اینهمه، او نقصی ندارد، و به وظایفش خیلی دقیق عمل میکند؛ پژوهشهایش کاملاً منطقی است، نویسنده میکوشد، تا الگوی نسبتاً مثبتی، از یک کارآگاه پلیس را، به خوانشگرش ارائه دهد؛

تاریخ بهنگام رسانی 06/12/1399هجری خورشیدی؛ 04/08/1400هجری خورشیدی؛ ا. شربیانی -

Το μεγαλειώδες χάρισμα της ειρωνείας που κρύβει λάμψη ψυχής!

Η ζοφερή διαθήκη της απόλυτης λογοτεχνίας γραμμένη απο τον ισχυρότερο μυθιστοστοριογράφο του 19ου αιώνα, κατακτάει όλους εμάς. Τους αναγνώστες. Τους απόλυτους κληρονόμους μιας ατόφιας περιουσίας που διαμορφώνει και στηρίζει σκέψεις και αξίες αιώνιες και απαρασάλευτες.

Βικτωριανή παράκρουση,φαντασμαγορία και κατάντια του Λονδίνου, το όραμα της Αγγλίας, ο λαβύρινθος των ανθρωπίνων δικαιωμάτων,των ατομικών συνθηκών, δοσμένα με ανθρωπολογικό περιεχόμενο που φέρνει τρόμο.

Μπορεί να καταστραφεί; Μπορεί να λυτρώσει;Μπορεί να ανασυσταθεί η κοινωνία που σαπίζει απο τη διπροσωπία του νόμου και τα ταξικά στερεότυπα;

Κοινωνικός ρεαλισμός και ρομαντικά στοιχεία σε απόλυτη ταύτιση. Αφήγηση που απογειώνει, καταρρακώνει. Ατμόσφαιρα και αίσθηση μυστηρίου. Αναπάντεχες συμπτώσεις.

Απρόσμενα κοινές μοίρες και οικουμενικά δράματα τόσο κοινά στον αναγνώστη που σοκάρουν. Τόσο σοκαριστικά που μόνο η μεγάλη τέχνη κατέχει και διαχειρίζεται.

Μέσα σε μια ιστορία εποχής περιπλέκονται και εξελίσσονται πολλές άλλες ιστορίες, πρόσωπα και καταστάσεις που όλα μαζί τόσο ξεχωριστά και τόσο ειρωνικά σχετικά μεταξύ τους ισχυροποιούν τη βασική υπόθεση και σε κατακτούν.

Λάτρεψα τον Ντίκενς για το βασικότερο γνώρισμα στον Ζοφερό Οίκο, την ειρωνεία του. Τη λατρεμένη ειρωνεία του για όλες τις εκφάνσεις των κοινωνικών ηθών και της παρακμής της Βικτωριανής Αγγλίας.

Λατρεμένος και αριστουργηματικός είρωνας,στηλιτεύει το δικαστικό σύστημα της εποχής. Ξεγυμνώνει τις προκαταλήψεις,τα στερεότυπα,τον πουριτανισμό,τη σεμνοτυφία, την ανάγκη της επιβίωσης που εφιαλτικά τυφλώνει και υποτιμάται.

Μια αρχαϊκή κοινωνία που κρύβεται απο την εξέλιξη και την επανάσ��αση και παραμένει κομμένη στα κλασσικά πρότυπα που φτάνουν ως σήμερα.

Η αριστοκρατία στην ονειρεμένη της φούσκα πλήττει απο ανία και υποφέρει απο την «ζοφερή πολυτέλεια της αδράνειας» και ο λαός πνίγεται στην πνευματική και υλική ένδεια χωρίς πυξίδα, χωρίς σωτήρες, χωρίς ελπίδες.

Ο Ζοφερός οίκος εξελίσσεται σε δυο διαπλεκόμενες αφηγήσεις.

Η μία αφορά τη ζωή της βασικής ηρωίδας Έστερ Σάμερσον και η άλλη την χιλιόχρονη δικαστική διαμάχη

«Τζαρννταϊς και Τζάρννταϊς» ειπωμένη απο έναν αφηγητή με πολυπραγμοσύνη.

Εμπλέκονται και σπονδυλωτά αναπτύσσονται δεκάδες ήρωες και καταστάσεις. Άλλοι φαινομενικά άσχετοι, άλλοι σοκαριστικά ύποπτοι,άλλοι μοιραία εμπλεκόμενοι, άλλοι πλούσιοι, άλλοι φτωχοί, άλλοι απάνθρωποι και μισητοί και άλλοι υπερβολικά καλόκαρδοι και συμπονετικοί.

Πλέκεται με απόλυτο σαρκασμό το γαϊτανάκι του Ζοφερού οίκου, της ζοφερής κοινωνίας.

Εξαιρετικά σύνθετη αρχικά η διαπλοκή των χαρακτήρων σιγά σιγά ξεδιπλώνεται και γίνεται απόλυτα κατανοητή.

Συναρπαστική μεθοδολογία γραφής, εξιστόρησης,απεικόνισης όλων των ειδών της ανθρώπινης φύσης σε όλες τις διαβαθμίσεις της.

«Όσο κακός κι αν είν’ ο διάβολος ντυμένος με ρούχα εργάτη ή αγρότη (και μπορεί να είναι πολύ κακός και με τα δύο), είναι ακόμα πιο πανούργος, πιο άσπλαχνος και πιο απαράδεκτος απ’ όσο σε οποιαδήποτε άλλη μορφή όταν στερεώνει μια καρφίτσα στο πουκάμισό του, όταν αποκαλεί τον εαυτό του τζέντλεμαν…».

Το βιβλίο καταγίνεται με το νομικό σύστημα, τις οικονομικές ανισότητες,τις κοινωνικές ιεραρχίες και φυσικά με τον τραγικό έρωτα.

Κύριο μέλημα του συγγραφέα να μας μεταφέρει το βάρος του «χρέους». Και το καθήκον μας για την εξόφληση του.

Το οικονομικό χρέος, το διαπροσωπικό,το οικογενειακό, το ερωτικό και αμαρτωλό. Αυτό το τελευταίο είναι άμεσα εξοφλητέο.

Μας καλεί έμμεσα στην προσωπική επανάσταση. Δεν μασάει τα λόγια του. Δεν γράφει πολιτικά, δημιουργεί λογοτεχνικά ερείσματα. Δεν παίρνει θέση. Είναι ένας λογικός αναμορφωτής. Μας επαναφέρει στην υποκειμενικότητα και στην απόλυτη εσωτερικότητα. Τα λεει, τα καταδεικνύει ολόγυμνα με την κραταιά τέχνη του λόγου του.

«...ούτε μια άγνοια, ούτε μια αμαρτία, ούτε μια κτηνωδία που έχει διαπράξει, που να μην εκδικείται κάθε κοινωνική τάξη, από τους αλαζονικότερους των αλαζόνων και τους ευγενεστέρους των ευγενών. Με τη σαπίλα, το πλιάτσικο και την καταστροφή, το Τομ παίρνει αληθινά την εκδίκησή του».

Μετωπική σύγκρουση βούλησης;

Έπος;

Τραγωδία;

Ορμέμφυτες ηθικές επιταγές;

Όλα αυτά υποστηρίζουν αυτή την αναγνωστική απόλαυση.

Ή ταυτίζεσαι ή δεν το διαβάζεις!

Καλή ανάγνωση!

Πολλούς εορταστικούς ασπασμούς! -

Nomen Est Omen, in the world according to Dickens!

But don’t take it literally, especially not when reading the title of Bleak House. For Dickens also requires you to read between the lines, and letters, just like in an acrostic poem:

BLEAK HOUSE

Lovely characters

Elegant prose

Agonising cliffhangers

Knowledgeable descriptions

Humorous plot

Outrageous social conditions

Unusual dual narrative

Suits in Chancery

Everlasting favourite

Yes, Christmas is approaching, it’s Dickens time. I spent it in Chancery this year. And what can I say? Bravo Dickens? No, I stole that Thackeray phrase for

David Copperfield last year already! Bravissimo, you fulfilled every single one of my great expectations, as did

Great Expectations? Yes, ...

I will just say a simple: “Thank you, Sir!”

I have spent delightful hours in the company of good and bad, funny and passionate, silly and intelligent characters, brought to life in inimitable prose. Where else can I laugh and cry and bite my nails at the same time, while bowing to the elegance of the sentences that follow each other like pearls on one of Lady Dedlock’s more expensive necklaces? Where else can I hate and feel compassion, and wonder at the immense difference between my contemporary world and the London society of Dickens’ times,- and yet recognise it anyway, for being almost identical? For could not Dickens’ short comment on the state of British politics have been heading a newspaper article in 2016, just as well:

“England has been in a dreadful state for some weeks. Lord Coodle would go out, Sir Thomas Doodle wouldn’t come in, and there being nobody in Great Britain (to speak of) except Coodle and Doodle, there has been no Government.”

Following my reading itinerary, from start to finish, I realise how much I grew to love the many characters, all different, but equally at home in the Bleak House chocolate box, some nutty, some sweet, some rather plain, others exotic. In the end, they all lived up to my expectations, from the very first encounter with the complicated lawsuit of Jarndyce and Jarndyce, which gives the novel its unique flavour:

"In which (I would say) every difficulty, every contingency, every masterly fiction, every form of procedure known in that court, is represented over and over again?"

And what a range of characters I met, circling around the two stable elements of Mr John Jarndyce and Miss Esther Summerson, a young woman who shares the narration of the story with an omniscient voice, so that the narrative is swapping back and forth between her personal experience and impersonal overarching description.

Some characters, like Skimpole, get away with sponging ruthlessly on others because of their presumed innocence:

"All he asked of society was, to let him live. That wasn't much. His wants were few. Give him the papers, conversation, music, mutton, coffee, landscape, fruit in the season, a few sheets of Bristol-board, and a little claret, and he asked no more."

It is not as innocent as that of course, as the story will tell!

Many characters have reason to be frustrated, and Bleak House inspired me to rename my workroom as well, in honour of John Jarndyce’s favourite place:

"This, you must know, is the Growlery, When I am out of humour I come and growl here. [...] The Growlery is the best-used room in the house."

There is no one like Dickens to introduce the reader to a love story in the making, simply by changing the tone used to add a small piece of information at the end of a long chapter on something completely unrelated:

"I have forgotten to mention - at least I have not mentioned - that Mr Woodcourt was the same dark young surgeon whom we had met at Mr Badger's. Or, that Mr Jarndyce invited him to dinner that day. Or, that he came."

Another favourite feature in Dickens’ novels is the punny sense of humour that appears over and over again, and shows off both his talent for and his pleasure at playing with words for their own sake, as well as his mastery when it comes to giving all his characters their own stage time, beautifully shown in the following short lesson in mental geometry and verbal comedy:

"But I trusted to things coming round."

That very popular trust in flat things coming round! Not in their being beaten round, or worked round, but in their 'coming' round! As though a lunatic should trust in the world's 'coming' triangular!

"I had confident expectations that things would come round and be all square", says Mr Jobling."

Sociologists must love Dickens too. There is more than just a little irony in the sermon that Mrs Snagsby takes to be literal truth, directly applicable to her faulty perception of reality. What a comedy show! A victim of her own imagination and jealousy, Mrs Snagsby interprets preacher Chadband's words as a revelation of her husband’s infidelity, which leads to her total collapse during a sermon, completely inexplicable to the rest of the assembled community:

"Finally,becoming cataleptic, she has to be carried up the staircase like a grand piano."

Meanwhile, Mr Snagsby, "trampled and crushed in the pianoforte removal", hides in the drawing-room. What a marriage!

The linguistic pleasure of reading Dickens should not be underestimated either. His vocabulary is diverse, rich, and sophisticated, but he does not shy away from repeating the same word over and over again, if he thinks it has a comical effect and suits the story line. He was clearly on a mission to ridicule the habit of having missions, when he introduced a whole society of different do-gooders who were absorbed in their own commitments and oblivious of the existence of anything outside their narrow field of vision:

"One other singularity was, that nobody with a mission - except Mr Quale, whose mission, I think I have formerly said, was to be in ecstasies with everybody's mission - cared at all for anybody's mission.""

As always, Dickens has a special place in his heart for his minor characters, and fills them with so much intensity that they could easily lead the whole plot. A favourite example is the Bagnet marriage. Mr Bagnet, knowing that his wife is a better judge of situations than he is himself, and worth more than her weight in gold, has a habit of letting her express "his" ideas whenever he is consulted about anything, for it is important to him that the appearance of marital authority is maintained:

"Old girl", murmurs Mr Bagnet, "give him another bit of my mind."

And then there is sweet, crazy Ms Flite, who sums up the tragedy of her family in a few lines of incredible suggestive power, showing the effect of long law suits on the dynamics of generations of people living in suspense and frustration:

"First, our father was drawn - slowly. Home was drawn with him. In a few years, he was a fierce, sour, angry bankrupt, without a kind word or kind look for anyone. [...] He was drawn to debtor's prison. There he died. Then our brother was drawn - swiftly - to drunkenness. And rags. And death. Then my sister was drawn. Hush! Never ask to what!"

Ms Flite herself is also completely guided by Jarndyce and Jarndyce in every aspect of her life. She follows the suit in Chancery almost like a contemporary woman would watch the interminable episodes of EastEnders, always expecting a "judgment", despite knowing that the ultimate purpose of the show is to keep the actors and producers busy, and the spectators in excitement. She cries when the show finally wraps up and she sets free her birds, named after the passions that constituted the essence of Jarndyce and Jarndyce.

That’s it for now? No wait, there is more!

Dickens is also a master of special effects, almost cinematic in nature:

"Everybody starts. For a gun is fired nearby.

"Good gracious, what's that?" cries Volumnia, with her little withered scream.

"A rat," says My Lady. "And they have shot him."

Enter Mr Tulkinghorn, ..."

And this shot turns out to be one of foreboding, for nothing happens without purpose and connection in Dickens’ world, and the story turns into a murder mystery. The man whose specialty was using secrets to control others finds his end with a bullet in his cold heart. What a good thing that Hercule Poirot has a worthy predecessor in Mr Bucket, who has the immeasurable advantage of being married to Miss Marple.

That’s it, now, finally? No! I can’t leave Dickens to tie up loose ends and make his surviving characters lead the lives they deserve, without mentioning the little boy who broke my heart:

"Jo is brought in. He is not one of Mrs Pardiggle's Tockahoopo Indians; he is not one of Mrs Jellyby's lambs, being wholly unconnected with Boorioboola-Gha; [...]; he is the ordinary home-made article. Dirty, ugly, disagreeable to all the senses, only in soul a heathen."

The description of how that illiterate, starving child’s heart stopped beating is one of the most touching moments in the whole story, along with the haughty, elegant Sir Leicester’s love and anxiety over his disappeared wife. In Dickens’ world, pity is to be found in very different places!

That all?

Nope! But I will be quiet now anyway …

Just stealing a phrase from Oliver Twist, and applying it to Dickens’ novels rather than food:

“Please, Sir, I want some more!” -

So what the dickens is all this bleakness about? If not about the weather, atmospheric and dreary - and playing its part from the opening pages, then it must be about the prolonged court case, played out through the book, of Jarndyce v Jarndyce. Perhaps it is the story of the two central female characters Esther and Lady Dedlock. Or maybe it is the timeless themes that run through all Dickens novels; the corruptive nature of power, redemption for the wicked, sacrifice of the good, and the undeniable force of class differences and wealth.

Well dear reader the bleakness comes from all of it. The emotions and drama that runs through all the individual plots and themes just spills out into the pages. The atmosphere and ever present sense of tragedy and sadness that cloaks a lot of the characters, most of whom hold a dark secret or they want to expose it. Whilst the book creates a sense of hopefulness, as a Dickens novel, you know lady ‘fate’ will have her way and it’s tragedy for someone.

Jarndyce v Jarndyce is a probate case, involving the Jarndyce family who challenge each other in court clocking up legal fees that might one day outweigh the value of the estate. Nevertheless, it is greed and fortune that can turn the eye blind to the inevitable.

Alongside this legal thread, are the stories of Esther, orphaned and cared for by her Godmother, and Lady Dedlock who possesses a melancholic air and who must at all costs hide her past transgressions to save her reputation and that of her husband Sir Leicester Dedlock. However, both lives become entwined as Esther finds herself a ward of Jarndyce and letters reveal some of the details of Lady Dedlocks secrets which fall into the hands of the notorious Tulkinghorn.

The story is long yet full of intrigue as we read our way through the deceptions, greed, revelations, loves and losses.

Review and Comments

What I loved about this book was the characterisation. Dickens is one of the best at developing his characters to the point the reader can identify with each one, their traits, their flaws and purpose. The Plot and the exposés were probably easy to work out part way through once the enquiries started into Esther, but what you could not foresee is how we arrive at the ending.

Whilst the writing in some of these great novels may not flow easily for the reader, I find the writing, descriptions, choice of words, and story telling superb. If you sit back and reflect on what you have just read, you can appreciate the sheer brilliance of Dickens. Because “A word in earnest is as good as a speech”

In some cases, Dickens conveys the emotions in other cases he hints at them. In some instances, he will reveal the plot and motive in other cases, he will leave it up to the reader to uncover the message, the connection, and the intention. Dickens is the master of suggestion - with perfectly timed comments, and subtle statements that come back later in the book and prove to be significant to the story.

I found the disreputable and dishonest characters more fascinating than Esther, a central character, who felt too good, too safe, and more like the poor but angelic little girl. I felt she lacked grit and real substance and felt too good to be true. I enjoy a bit more spice. Although intriguing the story was not sufficiently complex to warrant a book of this length. So it will feel a bit long, unless you just want to savour Dickens writing.

Excellent and although not my favourite Dickens novel, it is a timeless classic written by the master of character development who captures the immutable truth about human nature - perfectly. An author who writes beautifully, and can mix tragedy with love, honesty with deception but most of all an author who creates the drama and will leave you wanting to read more of his books.

Dickens is so good at penetrating your thoughts, that you find yourself reflecting on his stories, the plot, themes and messages a while after reading. Very memorable, often bleak but timeless. -

“Who happens to be in the Lord Chancellor’s court this murky afternoon besides the Lord Chancellor, the counsel in the cause, two or three counsel who are never in any cause, and the well of solicitors…? There is the registrar below the Judge, in wig and gown; and there are two or three maces, or petty-bags, or privy purses, or whatever they may be, in legal court suits. These are all yawning; for no crumb of amusement ever falls from Jarndyce and Jarndyce (the cause at hand), which was squeezed dry years upon years ago. The short-hand writers, the reporters of the court, and the reporters of the newspapers, invariably decamp with the rest of the regulars when Jarndyce and Jarndyce comes on…”

- Charles Dickens, Bleak House

One of the chief criticisms of the Anglo-American legal system is that it is slow. In civil cases especially – where a speedy trial is not guaranteed – the wheels of justice can move at a glacial pace. As an attorney, I can attest to this from firsthand experience. Certain actions can take years to even approach trial, much less ultimate resolution of the appellate process. In that span, lawyers come and go, witnesses die or disappear, memories wither, petty fights become drawn-out battles, and money – so much money! – just goes whirling down the drain.

There is nothing especially entertaining about this process. To the contrary, it is relatively disheartening to see the search for truth lost in a fog of discovery conflicts, pretrial motions, and endless depositions.

Thus, it should tell you something important about Charles Dickens’s Bleak House that the animating event is an infamous estate case that has been stagnating in chancery for decades.

That case – known as Jarndyce and Jarndyce – is a probate matter concerning a large estate that is shrinking daily due to attorneys’ fees, and is so tangled that no two lawyers can speak for more than a minute without disagreeing as to its purpose. In short, the testator (a.k.a. the rich, dead guy) has left numerous wills, leaving it to his heirs (and their lawyers) to determine the true document. If you are looking for a trenchant deconstruction of British civil procedure in the 19th century, your search is over.

(During a brief period moonlighting as an adjunct professor, I actually used Jarndyce and Jarndyce in my wills, trusts, and estates class, imparting practical pointers on how to avoid just this situation. Hint: thoroughly dispose of all prior wills).

Like many Dickens novels, Bleak House defies brief summarization. After all, it was a serial publication and Dickens had a lot of mouths to feed. The result is sprawling, ambitious, messy, and as convoluted as Jarndyce and Jarndyce itself.

The central figure of Bleak House is that Dickens staple: the orphan. The parentless child here is Esther, an insufferably bland protagonist that made me want to gouge out my eyes with the sheer banality of her existence.

Okay, that came across a little strong. Still, in an 800-page doorstopper, there needs to be some sort of center of gravity. As I’ll explain in a moment, Esther does not fit that description.

In any event, Esther is sent to live with Mr. John Jarndyce, who owns the wonderfully named manor, Bleak House. She is joined there by cousins Ada Clare and Richard Carstone, both potential heirs to the Jarndyce estate.

Esther quickly becomes the head of the household, and the saccharine nature of her existence is revealed. Though the identity of her parents is one of the novel’s central – and I would argue, transparent – mysteries, we are strongly led to believe that Esther descended from heaven on a cotton candy cloud. She is perfect in every way, except in the way that makes fictional characters into believable – or interesting – human beings. She lives only to serve others, and under her benevolent gaze, cousins Richard and Ada fall in love. If this is too Appalachian for you, don’t worry, because Richard also falls in love with Jarndyce and Jarndyce, nurturing a health-sapping obsession with obtaining the estate’s riches.

Dickens – truly acting like a man being paid by the word – spins out storylines with reckless abandon. In order to corral them all, he employs a critically lauded structure, featuring two parallel narrative tracks. One track is delivered in the first person by Esther, while the second is told in the third-person by an omniscient narrator. While these two tracks never quite intersect, or form into a satisfying whole, I certainly enjoyed my reprieve from Esther and her happy martyrdom.

While Jarndyce and Jarndyce is the tale’s spine, a great deal of time is also devoted to various love stories. Besides Ada and Richard’s hillbilly attraction, there are various men vying for Esther, that ultimate paragon of beauty, innocence, and sacrifice. One of these is William Guppy, a law clerk. Another is Dr. Allan Woodcourt, whose lack of any human frailty makes him a good match. Finally, there is John Jarndyce himself, who falls in love with his young ward. This might be creepy were Dickens’s world not so uniformly sexless. There is never any indication of passion or lust, just idealized, put-your-partner-on-a-pedestal “love.” Sex is nothing more than sitting in a room together, staring into each other’s eyes. I have often marveled at how Dickens – hewing to the conventions of his time – creates worlds that are simultaneously absolutely real and absolutely false. His descriptions of London, its fog and grit, are vivid and tactile, while his descriptions of human interactions – especially in the realm of romance – seem culled from a child’s collection of fairy tales.

As if dueling love stories were not subplot enough, there is also the aforementioned secret of Esther’s parentage, which seems to drag on for hundreds of pages, well after even a half-awake reader (such as myself) has solved the riddle.

Heaping complications atop complications, Dickens even throws in a late-inning murder. This allows him the opportunity to introduce English literature's first detective character, Inspector Bucket. I don’t think it’s a spoiler to say that Inspector Bucket is both dogged and clever.

I will admit that I have not come close to reading every Dickens novel, though it is a goal of mine. Still, he seems to be working from a familiar bag of tricks, including the bland orphan-hero, the questionable attorneys, the dizzying digressions, and a character who has been left at the altar and is now ossified by the grief of that moment.

Obviously, those tricks did not all work with me. Nevertheless, there is much to commend here.

Despite my lack of interest in the major characters, I was absolutely charmed by the secondary cast, many of whom are lively, quirky, wonderfully realized, and incredibly named. Long after I set this aside, I imagine I will be able to recall Mr. Skimpole, who manages to convince people to pay his debts by proclaiming a child’s inability to understand money. I also liked Mr. Tulkinghorn and Mr. Vholes, the two cunning attorneys with sharp minds and black hearts. These cameo roles serve their purpose, enlivening certain scenes so that Dickens’s headliners can continue moralizing at length.

While it’s tough to end a serial, I also appreciated (and was a bit surprised) that Dickens did not try to tie everything up with big red bows. Some characters die, others end up unhappy. The case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce is resolved in the manner that is to be expected. Esther is eventually beamed back up to her spaceship, having successfully conned everyone into believing that she was a human girl. If not wholly satisfying, it is satisfying enough.

With that said, it’s time to circle back to Esther.

I realize I am sort of piling on at this point. Yet, I don’t feel that bad, mainly because Esther is not a real person, nor could she ever be confused for one. To me, she’s a plaster saint. This non-dimensionality undercut my appreciation for Dickens’s brilliance. There were moments when Bleak House started to come together, and it was like viewing a vast and wonderful solar system, with beautiful stars and planets. Unfortunately, instead of orbiting a sun, all those stars and planets orbited a big black hole named Esther. The only complicating question in an uncomplicated character is what’s more irritating: her endless charity, goodness, and selflessness, or the fact that all the other characters continually tell her how charitable, good, and selfless she is.

I have a love-hate thing going with Charles Dickens. On the one hand, I like that he is accessible, that he works on such a broad canvas, and that he is formally daring. On the other hand, I feel like I have to separate a lot of chaff to get to the wheat.

I will acknowledge that I probably could have brought more patience to this literary endeavor. If I had read it at a different time, I might have enjoyed it more, and focused less on its flaws. With that said, I stand by my criticisms. Bleak House resembles a sprawling English country house, added onto over the decades. There are many wings and a lot of rooms. Some of them are grand, some are average, and some are populated with Esther and her cloying, ostentatious humility. -

What attracted me to Bleak House was the Chancery Court suit of Jarndyce V Jarndyce. Having always had an interest in stories with legal touch to them, it was natural for me to be drawn to the book. Besides, having learned that this book inspired a judicial reform movement which led to some actual legal reforms in later years and knowing the power of Dickens's satire and being curious to learn what in the story that truly inspired such a movement, I was most interested in reading it.

True to my understanding, the main part of the story is dedicated to the Chancery Court suit which is running for years without a foreseeable ending. Dickens, ever being the reformer, mocks the Chancery justice system which causes delays till the cases are passed from generation to generation. "The Lawyers have twisted it into such a state of bedevilment that the original merits of the case have long disappeared from the face of the earth. It’s about a Will, and the trusts under a Will—or it was, once. It’s about nothing but Costs, now. We are always appearing, and disappearing, and swearing, and interrogating, and filing, and cross-filing, and arguing, and sealing, and motioning, and referring, and reporting, and revolving about the Lord Chancellor and all his satellites, and equitably waltzing ourselves off to dusty death, about Costs. That’s the great question. All the rest, by some extraordinary means, has melted away." This powerful satirical criticism of the system very much impressed me. I have always enjoyed the satire in Dickens's works, but if he ever used that tool to his greatest advantage, it was definitely in this work.

In addition to the main theme, there are several subplots. All the subplots are connected to the main theme or its characters. However, some of the subplots have their own story as well. These subplots touch on different themes. Poverty is one; especially the plight of poor children who are abandoned or orphaned. It was heart-wrenching to read the subplot touching on Jo, a poor orphaned (or abandoned) child who lives a miserable life far more suited to an animal than a human. The compassion in which Dickens says the story of Jo brought me to tears many a time. Love and Duty are another. This theme is only secondary to the Chancery suit and occupies a major part of the story through the stories and characters of Esther, John Jarndyce, Ada, and Allen Woodcourt. Philanthropy is also another theme, and here both real philanthropy and pretensions are brought to light. John Jarndyce represents the true and real philanthropist who disinterestedly acts for the benefit of others. And there are some other characters who make a show of it. I truly felt that these pretentious philanthropists were representing the British government of the time. Dickens was a social reformer and raised his voice through his pen to lash at the government for its inadequate measures to improve the lives and living conditions of the poor. All these themes coupled with the mystery theme bring intrigue, colour, and variety to the book. Reading the book was like reading many different stories.

In Bleak House , Dickens uses a wide array of characters ranging from the aristocrats to the poor living in slums. In my reading life, I doubt if I ever have come across so many characters in one book. Although I have read reviews where it is commented that it was hard to follow so many characters, I didn't have any difficulty keeping track of them. Perhaps it may be due to my reading the book very slowly. The use of the different characters and a large number of them kept the story alive and moving. There was no reading minute that I felt to be boring. Many of the characters held my interest, but I liked John Jarndyce, Esther (our heroine, surprisingly new in a Dickens novel), and Allen Woodcourt the most. And my sympathy was freely won by Jo, Lady Deadlock, Ada, and a little grudgingly, by Richard.

One of the major writing tools of Dickens is his use of satire. In Bleak House, this tool is amply directed at every quarter. However, in addition to the satirical, philosophical, and matter-of-fact Dickens we usually meet, I also met a sensitive, sympathetic and compassionate Dickens in Bleak House. His prose is beautiful and the style is elegant, that even the too verbose parts were read with pleasure.

True to the title, the story is bleak, although there are few happy endings. But no matter how "bleak" the nature of the story was, it was a treat to read it. I truly enjoyed the read. Its diversity in themes, characters, and settings took me through a very pleasant and memorable journey. I have read that Bleak House is considered to be the best work of Dickens. While I may have my own opinion about that point, I can see why it's being so said. -

Reading Bleak House has had a redeeming effect for me. Before this marvel took place Dickens evoked for me either depressing black and white films in a small and boxy TV watched during oppressive times, or reading what seemed endless pages in a still largely incomprehensible language. Dickens meant then a pain on both counts.

In this GR group read I have enjoyed Bleak House tremendously.

In the group discussion many issues have been brought up by the members. First and foremost the critique on the social aspects has been put on the tray, but also the treatment of women and/or children, the critique of the Empire and of the Legal profession and institutions, the interplay between the two narrators, he humour, the richness in literary and historical references, the musings on ethics, etc. All this makes for a very rich analysis.

For me this book is certainly a reread. And apart from all the aspects above, what have struck me most, because it has surprised me, were the very rich plot and the way it was constructed. That is why, if I read Bleak House again, I will do so while drawing a diagram that, similarly to those charting engineering processes, would plot the plot.

Using an Excel sheet as my basis, the graph I have in mind would be a two dimensional chart, with the X or horizontal axis extending up to the 67 chapters of the book, while on the vertical or Y axis I would mark out three different bands. These bands would correspond to what I see as the main threads of the story. I am thinking of:

1. The Chancery, with all the Legal aspects. In this story line belong the Court itself, and the legal offices such as Kenge and Carboy and Mr. Tulkinghorn’s. The characters related to these legal aspects would belong to this band.

2. Esther, with her upbringing and Godmother. And here belong major characters such as John Jarndyce and the two Wards, Ada and Richard.

3. Chesney Wold, with the Dedlocks, Mrs Rouncewell and Rosa, etc.

Each chapter would be plotted according to its number and to the story band to which it belongs, and so it would be drawn as a square. To each chapter-square I would give one of two colors, depending on who is narrating it. When Esther is telling the story I would color the square pink, and when it is the Narrator, it would be blue. For the early chapters, Band #2 would be mostly pink, while the other two would be mostly blue; but as the novel advanced, I think the pink would begin to invade other band stories and vice-versa.

In each chapter-square I would include little cells, each one corresponding to one character as they first appear in the story. As the chapters advanced and the characters reappeared, I would draw connecting lines for those reappearing cells which would trace clearly how those character-cells started to move from story-band to story-band.

I wish I could draw the graph I have in mind in HTML format for this GR box. But to give you an idea, I think it would look like a combination of the following graphs:

and this:

Then I would also mark when some episodes or stories within the stories, were presented. To these I would give the shape of a sort of elongated bubble or ellipse and they would be superposed on the chapter boxes, since they would not quite belong, nor not-belong, to the three story lines above. In this ellipse category I place the episodes involving the Jellybys, the Badgers, the Turveydrops, etc.

Some of the characters, even if they first appear in the context of one of the bands, eventually move from one story to another a great deal. In the end they do not really belong to any one of them in particular. These characters I conceive as major connectors in the plot. I would then mark them with bold big dots linked by lines and would eventually look like a connecting grid. I call these the Connexions, and Jo, Mr. Guppy, Mr. Smallweed, amongst others, belong to this category. Mr. Guppy, one of my favourite characters, has a major “connexion” function although he is succeeded in his ability to precipitate the plot by the most determinant of the connecters, Mr. Bucket. As The Detective, his role is precisely that of connecting everything and thereby reach or propitiate the conclusion.

There is another group of characters who have a lighter connexion function, because they do not really advance the plot, but help in pulling it together and make it more cohesive. To this class I place Miss Flint and may be Charlotte (Charley) Neckett. As we draw further to the right of the X-axis, the connecting lines linking the pivotal characters become increasingly busy and tangled as they extend over more and more boxes. The connecting nodes would become something like:

By the end, as we approach the final chapters, all the story bands would have conflated into Esther, and the graph would become something like this one in which the central heart stands for the All-Loving-Esther.

And Charles Dickens planned all this without a Computer. -

Incredible - blows away any other Dickens that I have read (although it has been a couple of years). Now, there are issues with it: it FEELS long in a way that some great long books don't, which I think is due to the varying narrative stakes of the subplots; Esther Summerson, though delightfully written, is perhaps the most consistently GOOD character in the history of literature - you root for her but it is the rooting of a manipulated reader; and the absurdity of the coincidences is just downright staggering.

But, it's a huge achievement on 5 fronts.

1. On the line level, it's gorgeous. Dickens was on a roll for 800 pages. I am often guilty of skimming through landscape descriptions but not here.

2. The plot should seem Byzantine, but there are confluences of subplots and A plot that are massively satisfying, the love stuff is mostly juicy and good, there is a 70 page sequence toward the end that is so suspenseful that you'll read it in 2 seconds, and it is varied enough in voice that you mostly sail along with it. (A lot of the criticism I've read focuses on the alternating 1st and 3rd person - I really dug that and thought it was an accomplishment.)

3. I think a great book needs to have at least one completely unique scene that just sears itself into memory (e.g. the flood sequence in the Makioka Sisters). This book has it - the spontaneous combustion section is as good and creepy as anything.

4. The most important part for me; This is (even beyond Gaddis) the most generous book with tertiary characters that I have EVER read. 40-50 characters deep, and they are all unique, and well drawn, and quirky, and hilarious. A few favorites are Detective Bucket, who is a mixture of Gene Parmesan and Marlowe; the woman who loves her two ex-husbands more than her current husband; Mr Chadband, a preacher who "runs on train oil"; and the foppish Mr. Turveydrop. Throw in the exceptionally likable main supporting characters and it's a helluva cast.

5. it's really, really, really funny.

Bleak House is, I think, not quite as good as East of Eden, but it slots in with it nicely. It's epic, familially inclined, socially critical, has some great evil characters, and, as far as I have read, is an accomplishment beyond the rest of the author's oeuvre. Recommended, if you can spare it the time and the occasional eyeroll. -

Not gonna lie – as I have struggled to read I am also struggling to find the words to write reviews. Sometimes I am having luck and writing some reviews I am pleased with, but mainly I am just delayed in finding the time and motivation to put my review on the page. For this I apologize as I love communicating with my Goodreads friend through reviews. I currently have three books I have finished – one over a week ago – that I have yet to write a review for. So, nothing like chipping away at them the best I can!

Bleak House is a tough one to review anyway – even if I was not having reader/reviewer block. So, for this I am going to do one of my favorite form of reviews when I just need to brainstorm my thoughts. The famous “Bullet Point Review”. Prepare for stream of consciousness!

• I listened to this one. It had one reader. I think this would have benefited from multiple readers as I had a hard time distinguishing when it was Esther speaking. Normally I don’t prefer multiple readers, but I think it would have helped here.

• Spark Notes: Once again, a savior! I spent a lot of time on Spark Notes with this one. Every chapter. Sometimes it helped – many times I encountered the “Did I just read that?” issue.

• Despite any complications, I did enjoy this book. Not my favorite big book. Not my favorite Dickens. But, definitely decent.