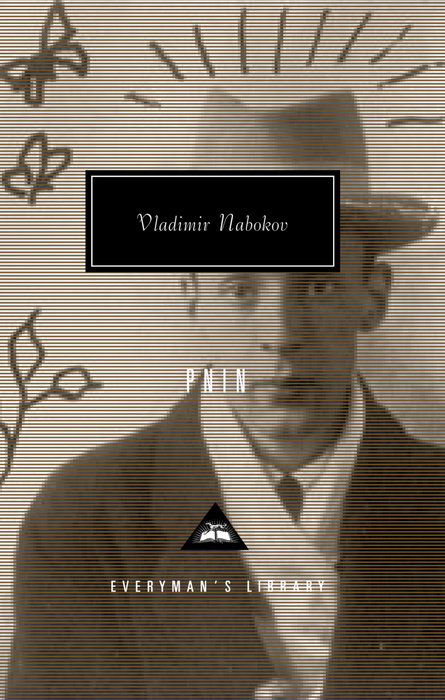

| Title | : | Pnin |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1400041988 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781400041985 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 184 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1957 |

| Awards | : | National Book Award Finalist Fiction (1958) |

Initially an almost grotesquely comic figure, Pnin gradually grows in stature by contrast with those who laugh at him. Whether taking the wrong train to deliver a lecture in a language he has not mastered or throwing a faculty party during which he learns he is losing his job, the gently preposterous hero of this enchanting novel evokes the reader’s deepest protective instinct.

Serialized in The New Yorker and published in book form in 1957, Pnin brought Nabokov both his first National Book Award nomination and hitherto unprecedented popularity.

Pnin Reviews

-

“Some people—and I am one of them—hate happy ends. We feel cheated. Harm is the norm. Doom should not jam. The avalanche stopping in its tracks a few feet above the cowering village behaves not only unnaturally but unethically.”

Pnin ~~ Vladimir Nabokov

I have never read anything like Pnin ~~ Nabokov uses language like no other writer I've read before. I am riveted by both this book and Nabokov's writing.

The strength of Pnin is its title character, Russian emigrate and professor, Timofey Pnin. A protagonist could hardly be more charming and lovable; Pnin's cultural and linguistic difficulties in adapting to America afford Nabokov plenty of opportunity for jokes and puns. The novel is astoundingly amusing, and the prose a sheer delight.

-

A promised land isn’t a land of milk and honey for everyone…

Now a secret must be imparted. Professor Pnin was on the wrong train. He was unaware of it, and so was the conductor, already threading his way through the train to Pnin’s coach. As a matter of fact, Pnin at the moment felt very well satisfied with himself.

Pnin is a stranger in a strange land – a learnt misfit in search of his singular niche… Don Quixote trying to defeat an especially malicious windmill.‘Yes,’ said Pnin with a sigh, ‘intrigue is horrible, horrible. But, on the other side, honest work will always prove its advantage. You and I will give next year some splendid new courses which I have planned long ago. On Tyranny. On the Boot. On Nicholas the First. On all the precursors of modern atrocity. Hagen, when we speak of injustice, we forget Armenian massacres, tortures which Tibet invented, colonists in Africa… The history of man is the history of pain!’

Is Pnin really a stranger or is he the only true human being among all those intriguing academicians? -

If one wanted to undertake a neat little study of Nabokov’s fictional prowess, they should read Lolita and Pnin back to back. They were written concurrently, in little middle-American roadside motels (the ones that are chronicled so abundantly in Lolita) during Nabokov and Véra’s summer-long butterfly hunting tours. Pnin was Nabokov’s antidote and respite from Humbert’s grotesqueries, the opposite pole of character, and we should marvel at the achievement that while he was creating the most erudite predator in the history of literature, he was at the same time moulding this Pnin from his most gentle clay, birthing his most sympathetic creature. The punning savagery of Lolita could not be farther away from Pnin’s sadly sweet sentimentality, and Pnin the book is the most touching Nabokov work I’ve encountered. Nabokov clearly loved this man, and while it is inevitable from page one that Humbert is a doomed, delirious soul, Pnin, whose doom seems always a hair’s width away, is almost kept from calamity by the reader’s sympathies for him alone- I challenge you to give this book a go and not get misty-eyed at Pnin giving water to a chirping squirrel (Pnin’s ever present squirrels; squirrel, from the Greek meaning “shadow-tail”; the “shade” behind Pnin’s heart; which Shade reminds one of that other novel where Pnin appears); Pnin ineptly attempting to extricate his automobile from a gravelly road; Pnin recollecting his beloved Misha under a sky stained red by sunset as he strolls among adumbral New England pines; Pnin dreaming his ghost father’s taking of a rook in a phantom chess match; Pnin breaking into hot tears at the cinematic depiction of a sun-struck Russian arbor; Pnin's defenestration of an unwanted soccer ball from a bedroom window; Pnin attempting to attain sleep through a backache as the wind ripples a puddle in the street, making of a telephone wire’s reflection the jagged angles of an ECG monitor; Pnin mustering quiet dignity and meticulously washing the dishes. Anyone acquainted with Nabokov’s biographical particularities can easily identify parallels between Pnin’s history and the author’s; but for Nabokov the private world was an impenetrable fortress, and any similarities that feed Pnin’s past should only be taken for what they are- inverse parallels, plays of imagination, refractions of a shared history that could be the story of many Russian expatriates who fled Fascism farther and farther west. Russia Abroad in the twentieth century is among the most fascinating literary diaspora, an inexhaustible well of insight into the limits of historical endurance. Pnin is a tenderly executed work by the man who continues to prove that he was the colossus of these wanderers- those who kept untouchable Russia alive and intact, at least in memory and imagination, wherever they might have been scattered.

-

I read this wonderful novel around the end of 1969, when I was drawing inescapably narrowing conclusions about the necessary but rather depressing ordinary events of my daily life at college.

It fit my mood perfectly.

All that winter and spring my moodiness grew as I was carried into the inevitable - and to me now, rather predictable - whirlpool of events commonly recognized as coming of age.

My identification with the hapless Professor Pnin, the eternal victim, had thus been made complete.

Shall I dare say here, that none of Nabikov's ironic and more acclaimed novels for me so much as held a candle to poor Pnin? For Pnin has seen through his own hopeless facades in such a humorous and self-deprecating way.

This novel made Nabokov famous and I have a sneaking feeling it was his undoing. He was every bit as shy as I am, and he would henceforth guard his personal life strenuously!

It's like making an image for yourself on Goodreads - one is always trying to up the ante. Woe to us if we think that. So had Nabokov perhaps henceforth believed - oh, deuce take it! - that he had "arrived?" A "sur chatiment" indeed for his innate timidity.

Sartre was right in saying a writer mustn't turn himself into something lapidary: for we are all fallible. So Nabokov became a Protean writer.

Fallibility is our very identity. No one "arrives." If he thinks he has, he is an arriviste, a very sad pejorative indeed. And Pnin is totally fallible.

You know, it was at about the time I was immersing myself in the chromatic chaos of Tristan und Isolde, that April, that I gave myself the urgent warning that I was being set up. I was not going to arrive anywhere, if I could help it.

I snapped out of Professor Pnin mode as best I could.

I henceforth, as that term ended, would search for "objective correlatives" (Eliot's apt phrase) for my malaise. I had subconsciously decided - as Mallarme might have done - not to be present for my awakening into adulthood.

I became a ghost in the machinery of my despondent mind. And my 'objectivity' force-fed my incipient paranoia.

***

Tonight I read that Nabokov's final tour de force - Pale Fire - was published concurrently with his seventieth birthday.

What shall I do for my seventy-third, arriving in a few months?

Probably nothing.

I'm done with doing bigger and better things!

For now, I'm quite happy again to be a mere Professor Pnin...

Back where I started.

But now, however, not as a ghost in the machine of my mind:

No: as a real, bumbling, very human and quite ordinary septuagenarian! -

The Revenge of Timofey Pnin

The traffic light was red. Timofey Pavlovich Pnin sat patiently at the steering wheel of his blue sedan directly behind a giant truck loaded with barrels of Budweiser, the inferior version of the Budvar he'd enjoyed in his Prague student days. On the passenger seat of the sedan, his paws resting on the open window, sat Gamlet, the stray dog Pnin had been feeding for the past few months, slowly encouraging the timid animal's trust. Gamlet had been unsure about the trip, reluctant to enter the car after Pnin had loaded the last boxes and suitcases and finally locked the door of the house he’d lived in for such a brief period. The dog ran around the yard in circles hesitating between going and staying until finally, much to Pnin's relief, he jumped on board.

But now Gamlet was looking back in the direction they had come with increasing anxiety.

Pnin glanced in the wing mirror. On the sidewalk, a man with a large and angry dog was hurrying towards them. The dog was straining at the leash, barking aggressively. Gamlet became more anxious and yapped madly in retaliation. Pnin recognised the dog immediately. It was Kykapeky’s dog, Kykapeky, the strutting director of the English Department, whose speciality was not Shakespeare or Milton or Wordsworth, but rather the impersonation of his unfortunate colleagues. Pnin knew himself to be the most unfortunate of the entire list. He had walked in on such impersonations many times, heard the sudden silence, seen people attempt to assume serious expressions. He'd felt the tension of modest guilt in the air, but noticed that some, like Kakadu from the French Department, didn’t even try to hide their sneers.

But the man holding the dog was not Kykapeky.

No, not Kykapeky, and not Kakadu either.

It was Kukushka!

Pnin had hoped to be well clear of Waindell University before his old rival arrived to take over the Russian Department, a department that Pnin had built by himself from nearly nothing. Pnin didn't suppose the man had changed much. He would be the same old Kukushka, taking, always taking, leaving nothing but discards.

And now Kukushka would take Gamlet too. The dog would surely jump out of the car window. When he did, Pnin would not stop to retrieve him. No, he would leave Gamlet on the sidewalk, leave him to Kukushka just as he’d surrendered many beloved things to that man in the past.

At that very moment the lights changed and the dog hesitated and Pnin accelerated as soon as the truck moved off, and he was away, striking west as so many times before. But this time, he was heading towards real freedom. As the blue sedan picked up speed, the dog stopped barking and lay down on the passenger seat and Pnin allowed himself to relax. He had escaped Kukushka finally and forever, leaving him to rot, alongside Kykapeky and Kakadu and the rest of the ptitsa, in the brackish backwaters of the miserable university town of Waindellville.

................................................

Index of Russian words used in this piece:

Gamlet = Hamlet, the prince of hesitation, and Pnin's favourite play.

Kykapeky = the sound a cockerel makes in Russian. The Head of the English Department in Waindell was called Jack Cockerell.

Kakadu = cockatoo. Kaka sounds like 'caca' which means 'shit' in French making the word particularly fitting for Blorenge, the Head of the French Department, who could barely speak French and thought Chateaubriand was a famous chef.

Kukushka = cuckoo, the robber bird, used here to stand in for the new Head of the Russian Department who had ousted Pnin in Waindellville as he had ousted him in Russia long years before.

Ptitsa = fowl, as in barnyard fowl

None of these names appear in Nabokov's novel - I've simply imagined what the very observant Pnin might have called his unpleasant colleagues, and his beloved dog, in the safety of his own mind.

................................................

Edit: October 6th

Pnin was my first Nabokov. I'm now reading

Pale Fire and I'm glad to see Pnin turning up on page 221 wearing a Hawaiian shirt. So he did go west!

And there's an index of foreign words at the end of Pale Fire, and lots of references to birds...

Edit: October 9th

I'm now reading

The Real Life of Sebastian Knight and on page 62, there's a reference to a possible book title, 'Cock Robin Hits Back', which along with the ornithological parallel echoes 'The Revenge of Timofey Pnin' a little...

Edit: November 25th

In

The Gift, the narrator mentions a review writer (he calls him a 'critique-bouffe') who liked to... provide the book with his own ending... -

Whilst a certain novel featuring a middle-aged man infatuating over his seduction of a 12-year-old girl was causing a storm in the literary world, along came the gentle breeze that was Pnin. Another remarkable character in a career littered with remarkable characters. After arriving in America in 1940, with wife Véra, and son Dmitri, as virtually broke refugees from Nazi-occupied France, Nabokov was able to find employment as a university teacher of Russian and comparative literature, first at in Massachusetts, then Cornell University in upstate New York. This clearly influenced Pnin. From an early stage in the development of the character of Pnin, Nabokov planned to write a series of stories about about the comical misadventures of an expatriate Russian professor on his way to deliver a lecture to a women's club in a small American town, which could be published independently in the New Yorker, which later was strung together to make a seriously good book. This proved to be a shrewd professional strategy. It also partly explains the unusual form of Pnin and how best to describe it. A short novel? a collection of short stories of set pieces? anyway, Nabokov poignantly sets about tracing Timofey Pnin's quest, which is ultimately frustrated, to find a home, or to make himself at home in the alien small town of Waindell.

Taking the small world pastoral campus setting, and removing the hustle and bustle of modern urban life, Pnin contains the fictional elements of different subgenres, but ultimately, this is quintessentially true Nabokovian territory, which goes about having a family resemblance to his other works without being exactly like any of them. For those who know their Nabokov well, it is full of allusions to and foreshadowings of those other works, especially Pale Fire (my personal favourite) where Pnin reappears, happily ensconced in a tenured professorship at Wordsmith College. Nabokov does not aim simply at a perfect match between his language and his imagined world. There are always strong reminders in his work where reality is larger, denser, and full of everyday occurrences encompassing his vision. Moments when the discourse suddenly seems to take off on its own and break through the formal limits of the story into the world outside the story, where the author and reader coexist.

Pnin himself is lots of fun to read about, even if he struggles to understand American humor, making this one of Nabokov's most joyous reads, he is particularly sensitive to noise and always hopes that the next house he moves to will be free of this nuisance. He is charming in his rambling ways and lectures, but cannot deliver a prepared speech without burying his head in the text and reading in a soporific monotone. He is obsessively careful, but still manages to get himself into awful jams. It's a character just so easy to fall in with. Lolita will always be the novel for which Nabokov will be best known, it went on to sell millions worldwide, and completely eclipsed Pnin in the public consciousness, but reading this again for the third time, just goes to set in stone Nabokov's very high standards, and a status of being one of the top novelists of the 20th century. -

I recently read Doctor Zhivago which Nabokov hated. You could say these two books are the antithesis of each other. Zhivago strives to depict a poetic vision of real life on a huge canvas and find meaning therein; Pnin is self-pleasuring art for art’s sake on a tiny canvas. Nabokov isn’t remotely interested in “real life” or deep meaning or huge canvases. He passes over the Russian Revolution in a couple of sentences whereas a description of a room that will only feature once in the entire novel is likely to receive an entire long paragraph. Wisdom doesn’t interest him much either except as a reliable source of caustic mockery. Psychotherapy is one of his targets in Pnin. Just as he mocks a lot of the devices favoured by novelists. There are two instances in this novel of Nabokov cleverly creating a great deal of sympathy for Pnin and in both he takes away our sympathy as soon as he’s got it. These involve Pnin catching the wrong train to an important lecture he’s due to give (he makes it there on time regardless) and of Pnin receiving a cherished bowl from his son which he believes he has destroyed when he lets slip a pair of nutcrackers into the soapy washing up water (turns out to be a worthless glass he’s broken). Pnin is constantly being misled by subjective interpretations of objective reality but it doesn’t really matter, it doesn’t do him any real harm. There’s a sense Nabokov thinks of everything as a storm in a teacup, even the Russian revolution and Hitler’s war, from both of which Pnin emerges unscathed as if they’re of little more importance than a thunderstorm. If you’re God there’s a lot of truth in this point of view and Nabokov can come across as believing himself to be a deity of sorts.

I’ve just read some of the negative reviews of this and the word “boring” crops up a lot. And depending on the page you’re on Pnin is either brilliant or, as these people say, can be a bit boring. That is to say it’s boring if you’re not a great fan of elaborate description of furniture, landscape or physiognomy. There is a lot of wordsmithery spent on ephemera. In fact I don’t think I’ve ever read a novel that so swiftly and frequently transited me from joy to boredom. There’s one of the best comic scenes in literature involving the hapless Russian professor, a squirrel and a water fountain. It’s comic genius but on anything but a superficial level it’s also meaningless, like one of those cute animal YouTube videos. That one scene maybe sums up this novel better than any review could – the slightly hollow interior behind the brilliant surface.

All in all Pnin is a pale understudy to Pale Fire in which he finds a dazzling form to poke fun at his targets here, exile into a foreign culture and academia. -

Cînd se afirmă că romanul lui cel mai bun e Lolita, cred că lui Vladimir Nabokov i se face o nedreptate, pentru motivul simplu că publicul cititor (amăgit de zarva nimfetei) tinde să-i ignore celelalte cărți. Și n-a scris puține. În ierarhia mea afectivă, Invitație la eșafod (roman scris prin anii 30, de un umor nebun) și Pnin (1957) sînt mai interesante și mai atractive decît Lolita. Recunosc, antipatia mea față de Lolita e veche și viscerală.

În 1955, Nabokov terminase de scris Lolita, dar nu găsea un editor (va găsi unul abia în Franța) și, pentru că era încă sărac, a acceptat să publice în The New Yorker (care plătea cu generozitate) extrase dintr-un nou roman. Cu condiția ca aceste fragmente să poată fi citite fără dificultate, ca niște povestiri de sine stătătoare, la sfîrșitul cărora nu mai era nevoie de un „va urma”. Așa procedase Nabokov și cu Speak, Memory (1951, ediție adăugită 1966), o autobiografie pe sărite, lacunară.

Pnin a revelat tuturor un prozator stăpîn pe uneltele lui, un artifex stilistic extraordinar. Întîlnim pretutindeni sintagme și adjective amețitoare: „Vederea nu era decît o durere ovală, cu străfulgerări oblice de lumină”. Pnin se înscrie în specia „romanului academic”, a „romanului de campus”, în terminologia lui David Lodge. Au fost pomenite în recenzii nume ca Mary McCarthy și Randall Jarrell. L-aș adăuga pe Kingsley Amis cu înfricoșătoarea-i satiră, Lucky Jim (1954), în care un asistent naiv, James Dixon, este tiranizat de șeful departamentului de Medievistică, odiosul profesor Welch.

Și Timofei Pavlovici Pnin pare o victimă a sistemului academic. A emigrat din Rusia și își cîștigă pîinea ca profesor la Waindell College. Într-o engleză îngrozitoare, distratul profesor Pnin încearcă să prezinte unui auditoriu mai degrabă indiferent prelegeri despre limba și literatura rusă. Pnin chiar este un aiurit (greșește adesea sala de curs, pierde toate trenurile care ar trebui să-l ducă la o conferință), un intrus, privit de colegi cu ironică uimire. În pofida stîngăciei sale, este simpatizat de studenți. Cînd folosește rusa în conversațiile cu prietenii, Pnin se vădește a fi un fin cunoscător al literaturii pe care o predă.

Unii critici au insinuat că în figura profesorului Timofei Pavlovici Pnin, Nabokov l-a „portretizat” pe unul dintre colegii de la Cornell University, Marc Szeftel. Mie mi s-a părut că Nabokov s-a caricaturizat în primul rînd pe el însuși... -

Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov is a little gem I will come back to again. Reasons being (a) it is so good and (b) I love the character Professor Timofey Pnin. I did get lost in a couple of passages. I think this is due to the writing of Nabokov as it’s a bit too clever in parts for me, but I will make a point of understanding the whole thing one day. But I got 90% of it – I think.

Pnin must have been a sight to behold, he had a bronzed bald dome, was clean-shaven and his absence of eyebrows were partially concealed by tortoise-shell glasses. He had a thick neck and a solid apish torso – but his legs were disappointingly thin, and his feet were almost feminine.

Pnin is a hapless academic at the fictional Waindell College in America, he’s an émigré, having to leave his homeland due to the Russian Revolution. We catch up with him, mostly, when he is in his fifties – but Nabokov does move the reader around chronologically, these changes in timelines were sometimes difficult to spot for this reader – hence, my confusion at times.

He was essentially homeless. He spent his entire career renting rooms from various faculty members. My favourite ‘room-lords’ were the Clements family. The father being a scholar offering a course on The Philosophy of Gesture, this family maintained a warm, understanding affection for Pnin throughout this story. His reasons for changing his lodgings so frequently (about every semester) were mainly sonic. Ha – I love that! He was also quite a particular man. For example, every lunchtime he washed his hands and head. I also loved the way he extolled the virtues of having all his teeth removed, to anyone who’d listen, and the author’s description of his meaty tongue exploring his now cavernous fleshy mouth.

Like so many ageing college people, Pnin had long ceased to notice the existence of students on campus

This story has a persistent ribbon of sadness running between the laughs. Poor Timofey Pnin seems to maintain his love for his ex-wife, Liza. In fact, she asked Pnin to look after the son of her second marriage (to the guy she left Pnin for) while she galivanted around – no doubt seeking a new suitor. Yes, she did marry a third time, but Pnin sobbed uncontrollably when he realised, she didn’t want to return to him. How sad. The son, Victor, did seem to be a nice lad though – small blessings.

….in a heated exchange between Professor Bolotov, who taught the History of Philosophy, and Professor Chateau, who taught the Philosophy of history: “Reality is Duration”, Bolotov’s voice would boom. “It is not” the other would cry. “A soap bubble is as real as a fossil tooth”

You know when you read a passage in a book and it sends you into hysterics? Well the following was one for me, I LAUGHED OUT LOUD: re-read it and LAUGHED EVEN HARDER.

…..the housekeeper was married to a gloomy and stolid old Cossack whose main passion in life was amateur bookbinding. A self-taught pathological process

I’m still chuckling.

Be careful though, as we are presented with some stark reminders of the grim times of the Russian Revolution, their Civil War and WWII. Such as the time Pnin reminisces about Mira, a Jewish girl he loved when he was young. Poor Mira ended up dying in one of Hitler’s concentration camps, soon after she disembarked from a cattle truck. This made me put the book down and think, and ponder and imagine this horror happening not once, but over six million times. How can one not feel despair?

“Pnin-ian English” was always amusing. Such as his persistent interpretation of Mrs Thayer as “Mrs Fire”. There are many examples throughout to saviour. Pnin finally found a house he wanted to buy; a small affair full of all sorts of “Pnin-isms”. Anyway, he held a house-warming party. Many people he invited found reasons not to attend, but the small gathering who did were all people who liked Timofey Pnin. There was a certain warmth about this gathering which I felt in my chest. I was happy for Pnin, and he did have a nice time.

I found myself liking the characters who liked Pnin and despising the ones who didn’t. I was certainly on Team Pnin and I don’t think I could be friends with “Anti-Pninists”. I think they would have a very mean soul to say the least.

The housewarming gathering occurs towards the end of this book, there is an interesting conclusion to the story – I won’t say if it’s happy or sad, for those of you who haven’t read this work. The narrator stays anonymous throughout but more information regarding this phantom player are revealed in the last chapter, which to this reader, was an interesting reveal.

What an absolute delight. I am so glad to have met Timofey Pavlovich Pnin, he will stay with me for a long time.

5-stars

Now to savour the reviews of others and check out some professional analyses. The fun on this one has just commenced. -

A heartfelt story of a hapless antihero. Pnin is an untenured professor of language and literature at a small upstate New York college. Born in Russia, he struggles with English to the point that others imitating his accent and malapropisms are the highlight of faculty parties. That provides a thread of comedy throughout the otherwise quasi-tragic novel.

There’s lots of other humor and good writing. Pnin walks behind ‘two lumpy old ladies in transparent raincoats like potatoes in cellophane.’ There are puns such as a ‘Dr. Rosetta Stone.’ Of an art professor the college “…was not particularly pleased either with Lake’s methods or with their results, but kept him on because it was fashionable to have at least one distinguished freak on the staff.”

Pnin is a bumbler. He gets on the wrong train going to speak to a women’s club. We’re terrified as we watch him learn to drive. We learn about the situation of Russian emigres as he is invited to a woodsy upstate B&B place in summers. They talk of their homesickness and who was killed by the Nazis or who has been imprisoned by the Communists.

Pnin has the additional misfortune of still being in love with his ex-wife back in Russia. She continues to ‘use’ him in amazingly atrocious ways.

The author is famous as a literary stylist and he uses an intriguing trick in the book. We think the story is being told by an omniscient narrator but there's an occasional ‘I’ popping up telling the story. We don't learn who this ‘I’ is until the end of the book.

We're treated to Nabokov’s erudition. You'll need a dictionary on occasion. We also read things like a discussion of how the timeline in Anna Karenina is out of whack. And we read the author's theory that Cinderella’s (originally Cendrillon) glass slipper was really a mistranslation of the French for squirrel fur vair as verre (glass).

Nabokov avoids overdoing the funny accent. But here’s an example when Pnin is asked for his address: “It is nine hundred ninety nine, Todd Rodd, very simple! At the very very end of the rodd, where it unites with Cleef Avhvnue. A leetle breek house and a big blahk cleef.”

An example of good writing: “Outwardly, Roy was an obvious figure. If you drew a pair of old brown loafers, two beige elbow patches, a black pipe, and two baggy eyes under heavy eyebrows, the rest was easy to fill out.”

Pnin is a short novel that Nabokov (1899-1977) wrote in English while he was a professor at Cornell (1948-1959). Pnin was serialized in The New Yorker magazine and it’s credited with bringing his work to the attention of American readers (including Lolita which had been published two years earlier).

Top photo of Nabokov (far left) and his siblings from acplwy.org

The author from bostonglobe.com -

A novel of college life.

Martin Amis in a review of

The Original of Laura has deemed it—along with VN’s Lolita and Despair—“immortal.” -

A little novel by Vladimir Nabokov features Pnin, an immigrant of Russian origin and professor at an American university; he's an endearing, distracted, and funny character that most of those around him consider a half-failure. He receives many tiles during his life, which the narrator gives us an overview of him. Most of the novel shows us its interactions with academia, and the author takes the opportunity to describe and portray it. The main attraction is the writing of V. Nabokov, which is sensational.

-

485. Pnin, Vladimir Nabokov

Pnin is Vladimir Nabokov's 13th novel and his fourth written in English; it was published in 1957. Pnin features his funniest and most heart-rending character.

Professor Timofey Pnin is a haplessly disoriented Russian émigré precariously employed on an American college campus in the 1950's.

Pnin struggles to maintain his dignity through a series of comic and sad misunderstandings, all the while falling victim both to subtle academic conspiracies and to the manipulations of a deliberately unreliable narrator.

پنین - ولادیمیر ناباکوف (شوقستان، کارنامه 2005) ادبیات؛ تاریخ نخستین خوانش ماه سپتامبر سال 2005میلادی

عنوان: پنین؛ نویسنده: ولادیمیر ناباکف؛ مترجم: بهمن خسروی؛ ویراستار بهناز بهادری فر؛ تهران، نسل شوقستان؛ 1382؛ در 271ص؛ شابک 9649346430؛ موضوع: داستانهای نویسندگان روس تبار امریکایی - سده 20م

عنوان: پنین؛ نویسنده: ولادیمیر ناباکف؛ مترجم: رضا رضایی؛ تهران، کارنامه، 1383؛ در 276ص؛ مصور؛ شابک 9644310470؛ نمایه دارد؛ چاپ دیگر 1393؛ در 302ص؛

در همان آغاز رمان، شاید اگر آن دره ی بزرگوار بین زبان روسی و انگلیسی وجود نداشت، آن بلا در سفر با اتوبوس، بر سر «پنین» نمیآمد؛ «تیموفی پنین»، شی��ته ی زبان روسی است، و با چنان ستایشی واژه های زبان روسی را ادا میکند، که گویی در حال خواندن اپرایی از موتزارت (موتسارت) است، اما این توان و آشنایی «پنین» بر زبان روسی، و شیفتگی ایشان به این زبان، همان چیزهایی ست که موضوع خنده، و مضحکه ی شاگردان انگلیسی زبان او هستند؛ این واکنشهای تند «ناباکوف»، به پیرامون خویش، به نوعی نتیجه ی همین سرگشتگی، بین سه گروه در ینگه دنیا است، و «ناباکوف» در بسیاری از مواقع، از این حمله ها، به عنوان سپر آفندی، سود میبرد؛ بهترین راه رخنه به جهان پیچیده ی «ناباکوف»، رمانهای ایشان هستند، و در اینراه باید این جمله ی «ناباکوف» را، هماره در پس ذهن داشت، که: «پنین خود من است.»؛

در رمان «پنین»، «ناباکوف» با واژه های خویش، به سه گروه، یورش میبرد، و میتازد

گروه نخست: انقلابیهای شوروی، و کسانیکه در کشور شوراها قدرت را در دست دارند؛

گروه دوم: روسهای ساکن آمریکا، آن دسته از روسهای بی بخاری، که مخالف انقلاب، و شیفته ی آمریکا هستند، و منتظرند شوروی از بین برود، تا با عزت و افتخار، به روسیه ی خویش برگردند؛

و سومین گروه: آمریکائیهائی که، هر چند استاد دانشگاه هستند، و از فرهیختگان جامعه به شمار میروند، از دیدگاه «ناباکوف»، در بلاهت و سطحی نگری، چیزی کمتر از دو گروه پیشین ندارند؛

در این میان، قربانی اصلی خود «پنین» است؛ مردیکه در بین این سه دسته گرفتار شده، و راهی ندارد جز آنکه در جنگل آمریکا، به مرز جنون برسد؛ مسئله زبان در رمان «پنین»، خود نیاز به نگارشی پر دامنه دارد

تاریخ بهنگام رسانی 26/04/1399هجری خورشیدی؛ ا. شربیانی -

Delightful! I can think of no other word to describe this book. It had me smiling on every other page and marveling at Nabokov’s wit. But of course the humor only thinly veils the underlying sadness.

Pnin is one of the most moving characters I’ve come across; infinitely amusing,stubborn, generous and poignantly insistent on protecting his own private universe.

Nabokov’s subtle satire of campus life is exquisite, as is his depiction of Russian émigré life. I read that he wrote Pnin simultaneously with Lolita, during the same road trip with his wife across America and that makes it all the more awe-inspiring. I particularly loved how the narrator sneaks in somewhere in the first half of the book, only to acquire a fully substantial presence by the end.

A Grand Master, indeed... -

تعايش نابوكوف مع أكثر من ثقافة خلال مراحل حياته وأجاد في تناول فكرة الهجرة في كتاباته

الرواية تدور حول شخصية ميتوفي بنين أستاذ اللغة الروسية في كلية واينديل الأمريكية

الأستاذ غريب الأطوار الهارب من روسيا إلى فرنسا وصولا للإقامة في أمريكا

وما يواجهه من عثرات ثقافية ولُغوية في محاولة التكيف مع الناس والحياة الجديدة

قد لا تتم الأمور بحسب ما يأمل أو يريد لكنه يتعامل معها دائما بروح طيبة وهزلية

السرد قائم على تفاصيل الأحداث والمواقف والشخصيات في حياة بنين في الماضي والحاضر

والحكي على لسان الراوي الذي يوضح صلته ببنين في النهاية -

The evening lessons were always the most difficult. Drained of ambulating the willing grey cells throughout the carnage of day classes, the young readers, almost resignedly, filled the quiet room at the end of the corridor. A subdued tête-à-tête, almost at once, broke into a charlatan laughter and the very next moment, died in their bosoms as Professor Pnin entered the classroom.

Straightening the meagre crop on his head and adjusting (and re-adjusting) his tortoise-shell glasses, he cleared his throat.

Pnin: Good Evening.

Class: Good Evening, Professor.

Pnin (cheerily): I am glad to see the attendance has brimmed to full today. [Pause] Alright then. Would all of you open your notes now? We shall take each one of your observations on Turgenev’s prose and discuss threadbare their meaning and implications on the Russian Literature fabric.

[Silence]

Pnin: Ladies and Gentlemen, please open your notes.

[Silence]

Pnin (in a mildly concerned tone): What is the matter? I can see your notes sitting pretty on your tables and yet you do not touch them? May I please be privy to your thoughts?

Josephine: Professor, we do have notes but they do not concern Turgenev’s prose.

Pnin: What do they concern then?

Josephine: You.

Pnin: Me?

Charles: Indeed Professor.

Pnin: But why?

Charles: Because that’s what is the homework we got – to analyse your publication on Turgenev’s prose, “Fathers and Sons – A Literary Bond”.

Pnin: No, no! I wanted you to read “Fathers and Sons” by Turgenev for analysis!

Eileen: Professor, you have given us the name of the wrong book then. Or perhaps we misunderstood your intentions. Again.

Pnin: What? But how is this…… (and his voice took a u-turn and trudged inside his mouth and jagged right into his head.)

Eileen (excitedly): But we have made some fascinating observations about you, Professor! You may like to hear them!

With the opportunity to assess the literary quotient of his class vanished like the hair on his head, he settled for the less worthy evaluation of their intelligence quotient.

Pnin (reluctantly): Very well then. You may show me the mirror, Miss Eileen.

Eileen: Actually, you began with the mission of dissecting Pushkin’s oeuvre but never got the book since you yourself had blocked it from issuing it to anyone else! I mean Professor Pnin had Pushkin allotted to himself in the system which he never got and could neither reallot it to Professor Pnin since it was always out of library!

Pnin: Yeees. It was an obscene revenge of the computer against my disdain for it.

Eileen (supressing laughter): And it happened often! But the university still kept you since it was fashionable to have atleast one distinguished fr*** on the staff.

Pnin: Fr*** ??

Josephine: Leave that, Professor! See, what I have found! Even your prodigal son, Victor, who delved in scholastic art from a tender age of four, could not decorate your limping English. Your reference to a noisy neighborhood as sonic disturbance, house-warming party as house-heating party, could pass, at best, as puerile. If your Russian was music, your English was murder!

Pnin: Why should I be a custodian of English when I know that Russian is a far superior language?

Charles: Perhaps because the former is more widely spoken?

Pnin: Ah, yes. (cheekily) My wife was good at it.

Charles: (competing cheekily) A little too good, may I add, Professor. She affirmed her proficiency by alluding an American Psychoanalyst in its lucid fold.

Pnin: Mr. Charles, you may refrain from making personal remarks.

Charles: Its YOUR publication we are taking about, Professor!

Pnin: I know, I know. Miss Josephine, do you have any more value additions?

Josephine: You went to great length to spread the sumptuous roots of Russian Literature; why, you took to Cremona on a wrong train! But your passionate erudition got you patient listeners and appreciative academicians.

Pnin: Thank you, Miss Josephine.

Josephine: You were also a strong and loving father to Victor as both of you, in abundance, were each other’s reflection – non-confirmists, impulsive, passionate and unrecognized scholars.

Pnin: Yes, I tried to be Victor’s shadow. He liked me, I think. Because I understood him. His artistic ebullience needed channelling into the right skies and I attempted to hold him aloft when he started stepping up.

Eileen: But you lost your link with Russian Literature, its prospective followers and your dear ones owing to your diminutive circle, subservient approach, vanilla judgement and ill-placed magnanimity.

Pnin (pensively): Yes, I have. But I haven’t lost my link with life. Yes, I have abandoned many parts of me; rather many parts of me have abandoned me like an ugly aberrant. But I believe there was some purpose in all of it. The purpose got clearer as the power of my spectacles increased; ironic as it may sound. Life is still like a long, beautiful Pushkin’s poem which I can read, once again, from the beginning and find new meaning in it. And if I ever struggle, I will have you good Samaritans to adjust my antennae.

Class (in unison): Yes Professor.

Pnin: Alright then. I thank you for spending precious time out and understanding my life..…

Charles (curtly): It was a homework, Professor.

Pnin: Ah yes. My apologies. Well, I will see you in three days then. Good night.

Class: Goodnight Professor. -

Video review

The passage where Pnin reads that magazine cartoon must be the funniest in all American literature! -

I would call this 1957 Nabokov novel a tragicomedy, leaning more to the comedy. Timofey Pnin is a likeable Russian emigre, a nice man, maybe too nice for his own good. Pnin is an assistant professor at fictional Wainsdell College, probably modeled after Cornell University where Nabokov taught. Even though Pnin has become an American citizen, he still struggles with the English language. He has difficultly being understood by his students and his colleagues. He makes his way through life in an honest and but prideful manner, but things never turn out quite the way Timofey would like them too. I imagine most of the academics and professors who read this novel see a little of themselves in Timofey Pnin, or at least in someone they know.

Wonderful character, excellent writing. 4 stars -

I had a professor, in fact he had no professor’s title, but we always addressed him that way. So, I had a professor who taught me maths. No, actually he was trying to teach me, he was doing his best to familiarize me with secrets of the queen of science. Alas ! I truly felt pity for him since I was stupendously immune to that knowledge. I was standing at the blackboard attempting to solve some mysterious to me equation and professor, waving his hand, would sigh then get out of my sight, please . Even today this recollection brings smile to my face. He was extraordinary teacher, demanding when it needed and lenient when he knew that his efforts after all would go down the drain. Fortunately for me he was not a type of crusader and knew which battles were lost before even started.

He used to accompany us to many school outing and I had opportunity to know him also from more private side. I remember, it was shortly after the shooting of John Lennon and we wanted somehow commemorate him, and professor then submitted the plan to plant the trees. So we went to the forest district and planted them. Lennon’s oaks. Or our wintry foray to the mountains and New Year’s Eve spent in the snowbound tiny church where brethren offered to us hot tea. It tasted exquisitely in that cold night.

He was charming man with great sense of humour. But there was about him, when I come to think about it now, some air of sadness and melancholia. I see him entering the class and throwing a register on his desk to stand at the window without a word for several minutes, sometimes even whole lesson. He came across as someone absent-minded and nonchalant. And a bit careless about his clothes in contrast to our other teacher who was very pedantic and used to wear his socks always under the colour of his shirts ( oh dear, these pink socks !). Oh, happy days.

I’m not sure where this rambling and digressive writing is leading me since I was going to write about Pnin and Pnin . But entering pninian universe triggered this stupid device called memory and I bogged down in own recollections. But I've got to say for myself that Pnin himself said you also will recollect the past with interest when old . -

Pnin is a character that I may see as a client, sitting across from me and discussing his life frankly. The tale is not tall, but genuine. He will discuss his love of Russian literature and his expertise in various areas. He will crack jokes that are just out of reach enough to make each of them a faux pas. He will unconsciously pull for affirmation of his status, wanting my acceptance and love. He will want to know that he matters. Under it, I will sense the glowing embers of a fire that has been forcefully put out – flames of yearning, connection, meaning. Pnin himself will have put this fire out, knowing that its exposure to the outside world will result in disaster. He has not been lucky in life. Love and vocation have not been kind to him. He protects himself. Is he putting on airs? Who knows. I think he is truly at a place where this is his life. There are chinks in his armour. There are moments where the glowing embers are painfully visible. He still has love for people that have come and gone. He still holds out hope that what he does in life will matter – and what’s more, may deliver him to “victory”. Whatever that means.

Not quite on the level of Lolita, yet still displaying its own quirky little charm and delights. Masterful as always. So far, my journey with Nabokov has brought about an awe – he is well in command of his language. Sentence construction is on point. If we are purely looking at writing, this should be a 5. My rating reflects my mood for the type of story that Pnin presents at this moment in time. I am leaving the door open for it to increase with successive reads. -

Several short stories about an absent minded professor rammed together and called a novel (but that’s okay, people do it all the time), Pnin is almost beloved by readers who aren’t me. Professor Pnin with his hilariously broken English is allegedly endearing but I was not even slightly endeared. This was footling stuff. He gets on the wrong train. He nearly misses giving an evening lecture. He buys a football for a kid who doesn’t like football. He doesn’t realise his job is on the line. He talks to people. Some of them like him.

So that’s how Pnin sank down to the two star basement. But of course Vlad the Impaler is one of the all time English language stylists, so he could be writing about - oh, say, the experience of getting all your teeth pulled out – and it would be heavenly :

It surprised him to realize how fond he had been of his teeth. His tongue, a fat sleek seal, used to flop and slide so happily among the familiar rocks, checking the contours of a battered but still secure kingdom, plunging from cave to cove, climbing this jag, nuzzling that notch, finding a shred of sweet seaweed in the same old cleft but now not a landmark remained, and all there existed was a great dark wound, a terra incognita of gums which dread and disgust forbade one to investigate.

But there is not enough of this grotesquerie and way too much description of rooms. My God, writers love to describe rooms! Describing rooms must be as good as sex for writers.

VN wrote Pnin while he was stuck toward the end of writing Lolita, as a kind of holiday from the horror, which is like if the Beatles stopped recording "A Day in the Life" to knock off "Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da", and if the melancholy uncomedy of Pnin gave VN the break he needed to complete his masterpiece, then I celebrate this very thin novel for that reason alone.

2.5 stars, rounded up to 3 to make me not look like an idiot - this is Nabokov! -

Аз съм била Пнин. Вероятно почти всеки е попадал в ситуация, в която е бил Пнин. Смутена, малко печална присадка на място, което непреклонно отказва да враства в себе си нови калеми. Дъждовна капка, самотно стичаща се по външната страна на прозореца. Влажен нос на куче, който не среща приятелски протегната ръка. Такъв е емигрантът Пнин в новата си (не)родина Америка.

Образът на простодушния професор по руски, „с чифт нозе като на жерав […] и крехки наглед, почти женски ходила“ е триптих, в който се срещат черти на самия Набоков, според теории – и на негов колега, както и чиста набоковска измислица. Пнин върши монотонната си преподавателска работа и кротко се опитва да намери дом за непретенциозния си живот. Получава кабинет в университета и се заема „обичливо да го пнинизира“, а понякога с пнинските си навици и най-вече с „пнинския фантастичен“ английски, който говори, се превръща в обект на подигравки от американските си колеги. Той сам за името си казва, че „втората сричка се произнася като „muff“ (несполука), ударението е на последната сричка, „ей“ като в „prey“ (плячка)“. Като че ли така го виждат и почти всички останали персонажи в романа – една руска емигрантска несполука, която спокойно могат да вземат като жертва за подбив.

Романът на Набоков е нещо като поредица от отделни разкази, където Тимофей Пнин, комично възпрепятстван от неспособността си да овладее езика на Новия свят, попада в ситуации, които неминуемо извикват съчувствена усмивка. Пнин е от онези тревожни симпатични хипохондрици, които честичко се безпокоят за здравето си по очарователен старовремски начин (той ми напомня и за дядото на Х., който още цитира съвета на майка си винаги да носи топли дрехи. И до ден-днешен носи терлици и жилетка и в най-големите жеги. Дядото, де). А Пнин всъщност има богат вътрешен свят, прекарва часове в библиотеката, където с тихо удоволствие прелиства прашасали томове и търси скучни до безумие факти, изпитва и сладка носталгия по своята Русия. Въпреки благосклонността, с която разказвачът в романа описва Пнин, в очите на другите той почти неизменно остава някакво безобидно недоразумение. Дори бившата му съпруга, психоаналитична кокетка с бездарни поетични амбиции, счита за уместно неведнъж да се възползва от неговото добродушие. Пнин има сходства и с романтизма на Дон Кихот, с неговото поовехтяло рицарско поведение и отминали идеали.

Владимир Набоков, самият той изгнаник в САЩ, се утвърждава като писател в Америка именно с „Пнин“, а не със своята вечна „Лолита“. Словесните еквилибристики в „Пнин“ и лабиринтите от думи, в които Набоков повежда, ме карат да изпитвам една неособено благородна завист към начина, по който си служи с езика („Пнин“, „Лолита“ и доста други негови романи са писани на английски, който не е негов майчин език). Причудливи метафори и необикновени сравнения изскачат от засада и карат нищо неподозиращия читател да се предаде с усмивка. Ето описание на устата на Пнин, след като са били извадени всичките му зъби:

„Езикът му — дебел, гладък тюлен — навремето тъй радостно шляпаше и се плъзгаше по познатите канари, като проверяваше контурите на малко пострадалото, но все още сигурно царство, гмуркайки се от пещера в залив, катерейки се по остра издатина, свирайки се в дефиле, намирайки вкусно късче водорасло все в същия стар пролом; сега обаче не бе останал ни един жалон — само голямата тъмна рана, terra incognita на венците му, а страхът и отвращението му пречеха да я изследва.“

Тъжно-смешен роман е „Пнин“. Спускаш се в дълбините на една осиротяла човешка душа, която в някаква степен си е самодостатъчна, но все пак съзнава, че има нужда от топлинката на други същества. Преди доста време бях гледала едно интервю с Дона Тарт, в което тя каза, че постоянно препрочита едни и същи книги и рядко посяга към нови. „Пнин“ беше една от тези книги. Ако Дона Тарт не може да познае многопластов роман като го види, то не знам кой би могъл.

„Пнин — с глава върху сгънатия лакът — заудря по масата с леко свит юмрук.

— Нищо си нямам — застена Пнин през паузите между гръмките влажни хлипове. — Нямам нищо, никого нямам!“ -

Coming from the master word-smith, a critic and the dictator of the reading choices of legions of readers comes a book backed by a blurb which compares Nobokov to a standard stand-up comedian with a professional capacity of making the audience laugh hysterically. Sad to say, the humour in the books failed to appeal me and was eclipsed by the unfortunate tribulations that influenced the demure and naive professor Timofey Pnin's reputation amongst his associates and the staff of the University.

The book starts with Pnin, an emigre(immigrant) Russian professor struggling with English, sitting in the wrong train while he is already late for his lecture and loses his luggage. He is constantly made fun of and is often undermined by his superiors and colleagues. The humour revolves around such events affecting Pnin. Although frivolous by nature, Nabokov's character and the events bring out sympathy out of me as a reader which overlaps the humour quotient in the book.It might preliminarily seem like Nabokov furtively describing his experiences through the character of Pnin but makes brief appearances himself directly addressing the reader and reflecting on tender topics along life and death in beauteous prose maintained constantly throughout the book-

I do not know if it ever has been noted before that one of the main characteristics of life is discreteness. Unless a film of flesh envelops us, we die. Man exists so far as he is separated from his surroundings. The cranium is a space traveller's helmet. Stay inside or you perish. Death is divestment, death is communion. It may be wonderful to mix with the landscape,but to do so is the end of tender ego.

As a Russian literature enthusiast it is heartening to see the names of Turgenev, Pushkin, Gogol, Chekhov, Tolstoy, Lermontov flashing through now and then and I regret not reading 'Anna Karenina' before reading this to completely comprehend Professor Pnin's unbounded admiration for the book reasoned by his concept described as 'relativity of literature' in 'Anna Karenina'. Nabokov makes subtle references to other such great works and takes pot shots at Dostoevsky whom he criticized. There is an episode in which Pnin's step son Victor talks about books

'Last summer I read Crime and ----' and a young yawn distended his staunchly smiling mouth.

The author vents his judgements and his reflections on books via the character of Pnin. It seems Pnin is Nabokov himself but he himself makes an appearance as an acquaintance of Pnin in the book.

Nabokov relies heavily on his prose style and is dependant on his verbal contortions where his characters live in a world revolving around objects with an harmonical wholeness which only Nabokov could have conjured with his masterful prose. His gleaming literary insights as shown in his pedagogical approach confounded my bleak understanding of the study of literature as a subject but that seems to be deliberate from the writer's side. It takes time to acclimatize to his writing pattern and the plot might seem stale but his playfulness shines through as he smoothly transitions through multiple digressions and ends in a cyclic fashion which is impressive in itself. -

Later Nabokov, oddly sweet compared with the more tart early novels. Bad poetry is savaged only once.

The eponymous Pnin, an ageing expatriate academic engaged in teaching Russian in small town America, is the hero of this oddly optimistic and even joyful novel. The wonder of putting trainers (Sneakers in certain jurisdictions) in the washing machine and listening to them running round or being taken as some kind of saint or angel as he sits broad smiling with a large Greek cross on his bare chest under a sunlamp outweigh the exile and failed marriage. Perhaps an alternative self portrait of the Author as a gangly optimist? -

Ich kann es immer noch nicht ganz glauben, was ich da gerade gelesen habe. Und dabei habe ich es zweimal hintereinander gelesen. Das war mit Abstand der schnellste Reread, den ich je durchgeführt habe. Ein grandioser Roman.

Ich war nach ein paar Tagen schon mit diesem kleinen Buch durch, als ich las, dass der große Ulrich Matthes das Buch 2003 eingelesen hatte und dafür mit dem Deutschen Hörbuchpreis ausgezeichnet wurde. Zufälligerweise war es sogar auf Spotify verfügbar, so dass ich einfach mal kurz hineinhören wollte. Ich konnte nicht abschalten und las parallel nochmal das ganze Buch mit. Matthes verleiht dem russischen College-Professor Timofei Pnin eine absolut überzeugende, mangelnde Sprachbegabung, dass erst durch seine einmalige Artikulation die skurrile Hauptfigur plastisch vor mir entstand.

Pnin ist ein armer Tropf mit einer guten Seele, der als Emigrant versucht, die neue Heimat in den USA lieb zu gewinnen, daran aber immer wieder scheitert, weil er die neue Welt einfach nicht versteht. Zudem ist dem Intellektuellen das genommen, was ihn jahrelang ausgezeichnet hat in seinem geliebten und vermissten Russland: die Kunst, mit Sprache virtuos umzugehen. Er tut sich schwer mit dem Amerikanischen, spricht es nur leidlich und stets fehlerbehaftet. Sein sonnengebräuntes, mondgesichtiges Äußeres und seine tollpatschige Art lassen ihn zu einem Original im schlechtesten Sinne werden. Er wird gerne parodiert und über seine Äußerungen und sein Handeln wird gelacht. In diesem Sinn ist er ein klassischer Tor, wie Candide, der Taugenichts oder Don Quixote, der oft als Vorbild in den Interpretationen herhalten muss.

Ich dachte gleich zu Beginn, dass Nabokov sich in Pnin selbst darstellt, denn der Werdegang des Autors scheint dem seiner erfundenen Figur sehr zu gleichen. Als dann aber am Ende des Buchs klar wird, dass der zunächst anonyme Ich-Erzähler Vladimir N. heißt, stellte sich für mich die Frage, wer Nabokov in dem Roman wirklich war. Oder ist es ein doppelter Doppelgänger? Der Schreibstil Nabokovs ist sehr raffiniert und detailverliebt. Jede Kleinigkeit wird exakt beschrieben, mit geschliffenen Adjektiven versehen und humoristisch ausgeschmückt. Ich habe selten so viel geschmunzelt beim Lesen, wie in diesem Buch. Lolita war ja bereits sehr gut geschrieben, unabhängig vom Thema. Pnin ist für mich aber nochmal eine Steigerung bezogen auf den Sprachstil. Zudem hat es der Autor hinbekommen, dass ich bei einer Geschichte über einen Toren nicht entnervt das Ende herbeisehnte, sondern jede Seite genossen habe.

Außerdem ist genau diese Ausgabe der Büchergilde Gutenberg eines der schönsten Bücher in Bezug auf Grafikdesign, Bindekunst und Illustration, die ich nun besitze. Pnin! Was für ein Buch. Es soll Schriftsteller geben, die kein Nabokov mehr lesen, weil sie das Schreiben entnervt aufgeben würden, da sie nie die Schreibfertigkeit des Russen erreichen würden. Ich kann sie verstehen. Wie schön, dass es noch so viele von mir ungelesene Romane von Nabokov gibt. -

Timofey Pnin … poor old fellow. You have been analysed to an extent you would otherwise only expect on a couch at the psychiatrist.

After all, you are only a slightly confused middle aged Russian male émigré trying to navigate in scholarly surroundings. You are not without ambition, you are capable in your own field, but you will never reach the halls of Ivy League.

You have taken with you the traditions and schools of thought from your homeland, but it is never enough to secure you the break-through you deep down feel you deserve.

On the other hand, you are somewhat content with what you have, and take some pride in being the stranger, the outsider, if only … if only you could understand the mechanism driving the circumstances.

Do you have a goal, a quest, somewhere you want to go?

This is the hard part. You are just paddling around in a small boat without rudder, and your compass is not designed for use in the land of the free.

I hope you forward journey will be a pleasant one, that you will find a place where you feel you belong. When your small car drive into the sunset never to return, I will miss you.

I will miss the way you demonstrate that life is not Instagram-perfect, but even the odd uncle do see glimpses of happiness once in a while. -

I’ve recently read

The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov. In those stories, he experimented and polished his craft. He is impeccable stylist and trickster. Through the years, it is evident in those stories how he has developed an arsenal of the original tools that he used in his bigger works. So when reading Pnin after those stories it was easier to see which rabbit (or rather a squirrel in this case) he would pull out of his hat.

I got used to the unreliability and general nastiness of many of his narrators. Here it was the one as well. I also anticipated the disdain to some fellow writers. Here, Anna Akhmatova and her early poetry seems to be the victim. Though the elegant cover up was that he parodied not her own style but the style of those young poetesses who were subconsciously imitating her. Mann, Dreiser and a few others received a dishonourable mention in passing as well. I also recognised his nostalgia for bygone Russian days and his snobbery towards academia in the US and elsewhere and pre-revolutionary middle class in Russia.

His playfulness with the language was familiar as well. Here though he took it on different level trying to play with two languages at the same time. I thought it was the bold and interesting decision to leave the poetry just transliterated. I am sure it should be quite special experience to be able to sound the words without understanding. Unfortunately for me, I knew the meanings, so I did not have this experience. He inserted a lot of Russian words and expressions. Sometimes, the translation that follows was not totally successful. I found it distracting. But again, I think it might be very interesting trick for an non-Russian speaker, something akin to the much easier version of "Finnegan’s Wake".

And he managed to make a circle in his narrative again. He has started the story with the visit to Cremona and he has finished it with Cremona as well. If I would see such trick for the first time, I would be incredibly impressed, but I’ve seen it before with him.

The Circle is the better example.

What was unique to this tale is its human aspect and kind humour. The main character is not very successful, but very sympathetic Professor Pnin. I hardly remember any other fully sympathetic Nabokovian character. Many scenes are genially funny. And though with the progression of the story, the narrator’s shadow becomes more visible over Pnin’s life, even the narrator fails to be sinister enough. And the squirrels are everywhere! They are even in the name of Pnin’s first love who is Belochkina. “Belochka” is a little squirrel in Russian. Normally there would be butterflies, so that was unusual as well.

I liked this diversion by Nabokov into a campus novel with the Russian twist. But personally I’ve started to expect from his work some kind of a tricky puzzle and deep layered intertextuality on the top of everything else. It was not the case here. Still, I was thoroughly entertained. -

Ciascuno di noi ha il proprio metro di misura per valutare un libro letto. A onor del vero la sottoscritta ne ha più d’uno, perché spesso è d’istinto, quando ancora sto sotto l’effetto della lettura appena terminata, che assegno le stelline, senza rifletterci (e magari ripensandoci dopo). Nel caso di “Pnin”, non è andata così, ci ho pensato e mi sono detta: “ Come posso non dare cinque stelle a un romanzo che durante la lettura mi ha deliziato per lo stile raffinato e brillantissimo, mi ha divertito e al contempo reso triste, mi ha fatto affezionare al protagonista e portato a schierarmi dalla sua parte in ogni disavventura che gli capita sopra? Come posso non dare cinque stelle quando durante la giornata, nel mezzo di una qualsiasi incombenza quotidiana, mi sono trovata a pensare a Pnin e a quale altra sventura gli potesse ancora capitare?”

Pnin è un piccolo (inteso come poco voluminoso) capolavoro, il cui protagonista -l’imbranato, distratto, maniacale, ingenuo, innamorato, puro di cuore professore universitario Pnin, nato in Russia, emigrato in Francia allo scoppio della rivoluzione e poi negli anni ’40 trasferito in America ad insegnare il russo- è un personaggio indimenticabile, un vero e proprio “uomo qualunque”, un ometto buffo che non si nota se non per prenderlo in giro per il suo inglese approssimativo, per il suo abbigliamento singolare e per le stranezze cui la limpida intelligenza lo costringe, come sapere a memoria il complicato svolgersi del tempo nel romanzo Guerra e Pace. Pnin è un omino dolce che desta ammirazione per la dignità e il candore, unico per la signorilità stile vecchia Europa che lo accompagna nell’indecifrabile mondo americano. Pnin è un antieroe tenero che desta compassione per il suo essere in bilico tra il nostalgico ricordo dell’infanzia nella terra russa e la fiduciosa speranza nel futuro di integrazione in terra americana, rendendolo di fatto senza radici, un dolce e svagato vagabondo, figlio, insieme alla straordinaria galleria di personaggi che gli stanno intorno, nato da un mix sapientemente dosato dal genio di Nabokov tra spunti autobiografici dello scrittore, personaggi del mondo universitario americano da lui conosciuti e protagonisti della letteratura russa, a partire dal Gogol de Le anime morte. -

Sumišę mano jausmai dėl šios knygos. Iš vienos pusės, nuvargino mane Nabokov’as su savo smulkmeniškais interjerų ir epizodinių personažų aprašymais, tačiau iš kitos pusės – rašo jis tikrai žavingai. Negali nesimėgauti.

Skaičiau šį romaną ne angliškai (originalo kalba), bet rusiškai. Tad, kaip suprantu, netekau autoriaus sumanyto niuanso apie profesoriaus Pnin’o nepuikią anglų kalbą, pilną žaismingų ypatybių. Vertėjas apsisprendė nedefektuoti profesoriaus kalbos rusiškame vertime, nes ji skambėtų apsurdiškai iš nepriekaištingai mokančio rusų kalbą Pnin’o lūpų. Kažin koks bus lietuviškas vertimas? Lyg ir greit turėtų pasirodyt.

Labiausiai mane suintrigavo Nabokovo ''žaidimas'' su atmintim/ prisiminimais. Šiaip jau, man pati romano pabaiga pasirodė geniali.

Beje, knyga gali pasirodyti panaši į Williams’o “Stoner”bet tik paviršium. "Pnin'' - liūdnesnis, mįslingesnis tekstas ir kabina kitas temas. Greičiausiai svarbiausia is jų - emigranto tema.

Papildymas.

Jau yra lietuviškai. Išleido leidykla RARA. -

(Riletto, avevo assegnato quattro stelle, ma come si fa ad assegnare solo quattro stelle a Pnin!)

«Il mio nome è Timofej» disse Pnin, mentre si accomodavano a un tavolo vicino alla finestra nella vecchia e malandata trattoria. «Seconda sillaba pronunciata con “uff”»

Che libro Pnin! 180 pagine in cui se non c’è quasi tutto, beh c’è parecchio. Tutti siamo il Pnin di qualcun altro. Pnin il professore di letteratura russa, impacciato, che però sa giocare a croquet, pelato, cinquantenne non in forma, con denti nuovi, dall’eloquio a suo modo affascinante, conosce l'inglese ma non sa pronunciarlo, spiega ai presenti saputelli che Anna Karenina non comincia un giovedì, bensì un venerdì, esattamente venerdì 23 febbraio 1872. Poi si distrae. Pnin che sa essere taciturno perché si sottrae rigorosamente ai commenti sul tempo. Pnin non afferra l’ironia americana. Pnin può sbagliare treno e sbagliare copione da leggere, sua moglie Liza lo ha lasciato per un altro, ma egli è disposto ad aiutarla economicamente ogni qualvolta quest’ultima si sia stancata degli altri uomini, perché Liza si stanca ripetutamente mentre ricorre alla psicanalisi per curare i guasti del suo umore, tuttavia Pnin non è certo che l’analisi sia un buon metodo. «Perché non lasciare alla gente i propri dispiaceri personali?». Sono una delle poche cose che si possiede veramente. Qui parla Nabokov, ma Nabokov non è Pnin. Pnin è Pnin: un personaggio che si inventa, si rinviene, mentre lo si va scrivendo.

Quando Pnin si reca alla fermata del bus per aspettarla scambia Liza per almeno quattro donne diverse, che da quattro distinti autobus salutano coloro i quali - come un trasognato Pnin - le stanno aspettando al capolinea.

«Sai, Timofej, questo tuo vestito marrone è un errore. Un gentleman non porta il marrone»

“Durante gli otto anni in cui aveva insegnato a Waindell, Pnin aveva cambiato alloggio - per una ragione o per l’altra, ma soprattutto per ragioni acustiche - all’incirca ogni sei mesi. L’accumularsi nella sua memoria di quel succedersi di stanze somigliava ormai a quelle esposizioni di sedie a braccioli assembrate, e letti, e lampade, e angoli di focolare, che ignorando ogni distinzione spazio-temporale, si mescolano nella luce morbida di un negozio di mobili mentre fuori nevica, e il buio si infittisce, e nessuno vuole davvero bene a nessuno.”