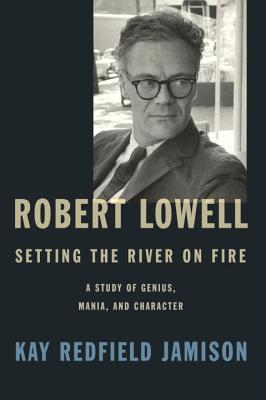

| Title | : | Robert Lowell, Setting the River on Fire: A Study of Genius, Mania, and Character |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0307700275 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780307700278 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 404 |

| Publication | : | First published February 28, 2017 |

| Awards | : | Pulitzer Prize Biography (2018) |

In his Pulitzer Prize-winning poetry, Robert Lowell put his manic-depressive illness (now known as bipolar disorder) into the public domain, creating a language for madness that was new and arresting. As Dr. Jamison brings her expertise in mood disorders to bear on Lowell’s story, she illuminates not only the relationships among mania, depression, and creativity but also the details of Lowell’s treatment and how illness and treatment influenced the great work that he produced (and often became its subject). Lowell’s New England roots, early breakdowns, marriages to three eminent writers, friendships with other poets such as Elizabeth Bishop, his many hospitalizations, his vivid presence as both a teacher and a maker of poems—Jamison gives us the poet’s life through a lens that focuses our understanding of his intense discipline, courage, and commitment to his art. Jamison had unprecedented access to Lowell’s medical records, as well as to previously unpublished drafts and fragments of poems, and she is the first biographer to have spoken with his daughter, Harriet Lowell. With this new material and a psychologist’s deep insight, Jamison delivers a bold, sympathetic account of a poet who was—both despite and because of mental illness—a passionate, original observer of the human condition.

Robert Lowell, Setting the River on Fire: A Study of Genius, Mania, and Character Reviews

-

This is an absolutely stunning portrayal of the manner in which Robert Lowell's complex poetry was shaped, determined and Perfected by the persistent progress within his psyche of the Daemon of Bipolar Disease.

All of us victims of that illness have seen ourselves repeatedly humiliated by it. It can be ugly in the extreme.

The trick to healing, you see, is to contritely ACCEPT the Full Force of your embarrassment, and the fact that we'll never be healed as long as we engage in that Daemon's rebellion against all that is right, decent and proper.

We have to know our Daemon's dirty tricks like the back of our hand. We are actually his real target - NOT the establishment!

But Lowell wouldn't listen, for he danced to a different drummer. He was a Genius; and healing would mean his banal anonymity.

He didn't want to take on the rags worn by a Nobody in the world's eyes.

Brought up a pampered kid in a connected family of Bostonians, with his moral conscience he became deeply conflicted. That conflict subsequently spawned deep mental illness.

He needed warm attention. It was his drug of choice. Along with the thrill of raw, rugged emotion - something much too indiscreet for his patrician parents.

Like the Eagles, he Took it (his Life) to the Limit.

And paid the Full Price, finally, in an early death.

Peace and wisdom are the real Pearls of Great Price -

Not his constant gaudy and dizzying insights -

The terminal trophies of a Leering Daemon. -

The public, the student, and even health-care practitioners need more biographical exposure to people with mental illnesses. The only way to really grasp the nature and diversity of mental illness is via empathy. Brains have no moving parts and x-rays, MRI's and autopsies come up decidedly short for imparting understanding. More importantly, mental illnesses frequently need an intimate, real - world perspective to be best understood. Kay Redfield Jamison helps fill this gap with a study of Robert Lowell.

Writing as an academic, Jamison presents a biographical dissertation on Lowell, the patient and the poet, that trends to unabridged. However, even to someone unfamiliar with the man, she brings him alive in a manner that engages. I received this book in a giveaway lottery - I am not deeply into author biographies. Hence, twenty percent of the way into it, I wondered if I would finish it given its narrow focus on someone with whom I have little familiarity. I am pleased to say that I did and am glad to have done so. Jamison writes in an energized style. She has a talent for keeping every paragraph vibrant in the manner of a first - rate fiction writer, let alone an academic. But the book is anything but fiction, and the fact that it is not adds to its richness.

The book has one structural weakness that the reader can remedy on their own if they know to do so. Mania, in and of itself, is fascinating and complicated. By the third chapter, I wanted more medical background to better appreciate the poet. Half of the way through, I craved it. Jamison had me hooked, but I was not appreciating all that she had to say about Lowell's life circumstances. She brings the disease alive at Chapter 9 and again in Chapter 13 (the best of the book).

Jamison does give a fine clinical description of the disease. Unfortunately, she has hidden it in Appendix 2. In future editions, it should be worked into the main text after the 2nd or 3rd chapter. I encourage the reader to start with the appendix or check it within the first half of reading the book. Mental illnesses are very diverse and poorly understood by the public and very often by doctors as well. Lowell's life needs to have maximum context from the beginning to best orient the reader.

The book's subtitle lists genius, mania, and character as topics. The text is strongest on the topic of character, then mania, and lastly genius. Given the order, some more space could have been allocated to his poetry with a few more examples showing where his genius lay early on. A larger amount of direct commentary on the verse would be helpful to tie it to Lowell's mania. Redfield does note, "manic patients use more adjectives and action verbs and more words that reflect power and achievement," but these points could be referenced to specific verse examples more frequently. It is not entirely clear how Lowell has more genius than other poets. Chapter 13 brings his writing alive (it is about death, after all) in the more dissected manner that poetry often requires for a novice to quickly appreciate. My own unfamiliarity with Lowell limits my full appreciation of Jamison's work in this regard.

All in all, a rewarding read to the amateur and undoubtedly mandatory one for the literary scholar. We hear about the relationships between mental illness and talent often to the point of cliche. Setting The River On Fire brings said relationship into valuable focus and adds depth to our knowledge of mental illness and talent generally. -

Ugh, the writing is just deadly. I've been constantly looking for other things to do so I don't have to pick this up. That means it's time to move on.

-

In her book, Robert Lowell: Setting the River on Fire, Kay Redfield Jamison sets herself an unenviable hydra-headed task: She wants to write a psychological account of Lowell the poet and the man, she wants to connect his bipolar disorder to his creative accomplishments, and she wants to leave the matter of Lowell's biography more or less in between the covers of Ian Hamilton's biography of Lowell. She also wants to demonstrate the Lowell's bipolar disorder was hereditary (she does this), and she wants to background us on reports of bipolar disorders as far back as the ancient Greeks (she does this, too.) And finally, she wants to offer us glosses on Lowell's poetry that reflect her sense of the connection between psychology and poetry.

Lowell's life was rough. He was a difficult child with a cold, controlling mother and a weak, feckless, wife-dominated father. He came from the long line of distinguished New England Lowells and by his second year at Lowell House at Harvard, he couldn't stand another day of his heritage or Boston or New England. So off he went to Vanderbilt and then Kenyon and more or less found himself as a poet-in-becoming...only to dive into a tumultuous marriage with the writer, Jean Stafford, that ended as badly (for her) as his subsequent marriages.

As he passed through his twenties, Lowell's bipolar disorder worsened. Redfield explains this disorder expertly (she's an expert, after all, and suffers from bipolar disorder, too). In short, the disorder has three phases: mania, which means uncontrollable behavior and thought, remission, which means the patient is okay, and depression, which means...you guessed it. In Lowell's time, this disorder was classified as manic-depressive. There wasn't much effective treatment available except institutionalization and electro-shock therapy; Lowell therefore was institutionalized and electro-shocked many times. Eventually, lithium proved to be very helpful in staving off the cyclical return of mania, and Lowell benefited from that...when his heavy drinking and confused life didn't lead him to neglect his meds.

Somehow--Redfield attributes this to character more than anything else, plus a quotient of genius, of course--Lowell managed to write many of the 20th century's great poems. He was a prize-winner, much anthologized, and well-respected by predecessors like T.S. Eliot and contemporaries like John Berryman, Elizabeth Bishop, and Randall Jarrell.

But all was not well...all was often chaos. Redfield partially leaves the ugliness of this chaos to Hamilton's biography, I gather, omitting the cruel, savage specifics of Lowell's breakdowns, his assaults on those around him and his infidelities to his second wife, Elizabeth Hardwick. Her thesis, which I guess is true, is that Lowell really couldn't help himself and he has been unfortunately diminished, poetically speaking, by the grim facts of his spells of mania. There's a lot related about these manic spells, to be sure, but I had the sense that Redfield wasn't really offering a full psychological account of Lowell's time on life. That said, I don't think I will read Hamilton's biography because, as Redfield explains, Lowell was out of his mind when he was at his worst.

Redfield herself is an estimable writer, truly gifted. Her appreciations of Lowell's complex poetry--a mix of cosmic meditation, historical exploration, and autobiographical exegesis--are superb. Lowell was, at his best, unquestionably a terrific poet. He had an uncanny knack for taking New England several steps beyond Robert Frost, taking it on more frontally, accepting it more fully.

But Lowell's was a cheerless life and it was a destructive life. Redfield can't avoid dealing with that since it became, increasingly, the subject of his poetry. As wonderful as he could be when he wasn't manic or depressed brilliant, eloquent, penetrating), he did a few awful things when he wasn't manic or depressed as well. For twenty years, his second wife Elizabeth Hardwick saw him through desperate collapses. Then he went off to England and "fell in love" with a very naughty, alcoholic, but quite pretty heiress of the Guinness clan, Caroline Blackwood. That led him to divorce Hardwick and marry Blackwood and have a wretched up and down time with her. When he became manic again, she wasn't up for sticking around like Hardwick. Others had to manage him. Ergo, Lowell divorced Blackwood and "went back" to Hardwick. Worse, he published a book of poetry that exposed the gist and text of many letters Hardwick had written him during their pre-divorce break-up...and he put himself in the position of a poor guy over whom two women were fighting. Hardly the case.

I presume this explains why Hamilton's biography put the nail in Lowell's reputation for quite some time. I also wonder why Redfield doesn't take head-on the vanity/egotism of Lowell writing about Hardwick in demeaning ways. She cites Faulkner saying something about art above all, kill for art, never compromise your art (it's a famous quote, you can look it up), but Faulkner also said he reread Don Quixote every year, which was nonsense, too. Elizabeth Bishop, Lowell's close friend, had it right when she wrote to him that art wasn't worth such destructiveness.

Another concern I'd like to raise has to do with the implicit judgment Redfield seems to offer that Lowell's extensive and surprising revisions of his work reflected some kind of gift from his madness. I do think that madness might heighten a talented artist's perceptions, but many, many poets and prose writers revise their work dozens of times, turn it around, twist it, pound at it until they understand what it is they are trying to say. That's not especially bipolar. It's just commonplace artistic obsession with getting things right. Here what we see--the poet at work--is exactly what Redfield means by Lowell's character.

I don't know if Redfield manages to rescue Lowell with this book or if that really was her deepest intent. She handles so much material, so many angles, so many inherent contradictions, that she no doubt achieves many goals, but like Lowell, they are somewhat confused. -

My only complaint is that it got a little long and tedious, but this is a brilliant portrait of a complicated, talented man. Jamison's prose is gorgeous. I listened to the audio book and at times couldn't tell if she was quoting Lowell's poetry or writing her own descriptions. It was often the latter.

-

Mental illness is trending throughout the news threads these days, but it isn’t necessarily trending in a helpful way. People on both sides of the gun debate seem to agree that mental health issues should be addressed in a better way than it is currently being addressed, which is, of course, not at all. The problem is in the stigma, misinformation, and stereotypes that still plague the general public regarding mental illness.

Our knowledge of mental illness---who it affects, what it is, how to treat it---has improved somewhat in the past century, ever since psychiatry and psychology have been accepted (somewhat) as real science, but what we don’t understand about the mind and its many tendencies to malfunction has continued to be a problem for many people, not the least of which are the people suffering from mental illnesses.

The stigma that made mental illness such a taboo subject for centuries, forcing families to dump loved ones in horrible insane asylums and institutions where they would stay locked up until they died, still exists in the embarrassment and shame many people have when it comes to talking about their own illness. Even the millions who suffer from the most mild forms of depression are still, sometimes, hesitant to talk about it, and rightfully so, when so many people don’t understand that depression isn’t simply “feeling sad” and that a good cry and some positive thinking isn’t nearly enough to cure it.

Misinformation abounds in the public forum mainly because this stigma still lingers. Vocal anti-psychiatry advocates like Tom Cruise---who claims that psychiatry is a “pseudoscience”, that chemical imbalances in the brain are “imaginary”, and that psychotherapy is “dangerous”---unfortunately have weight in many people’s minds because they, themselves, don’t know much about psychology and because, well, Cruise’s stultifyingly misinformed (and Scientology-based) contrariness resonates with a burgeoning anti-intellectualism in this country.

It doesn’t help that Hollywood still can’t seem to provide a portrayal of mental illness that doesn’t fall into one of two camps: 1) psychopathic killers, or 2) frighteningly pathetic victims of a tortured psyche whose only recourse is a strait-jacket and a padded cell. What about the millions of mentally ill people who still manage to lead productive lives? What about the millions of people who, in some cases, see their mental illness as not necessarily a bad thing?

Thankfully, occasionally, a movie or a book will get it right.

Kay Redfield Jamison’s biography/case study/literary analysis, “Robert Lowell: Setting the River on Fire” is notable and excellent for many reasons. Besides being beautifully written, Jamison also comes from an extremely informed position in her approach toward the poet, Lowell. She is not only the Dalio Family Professor in Mood Disorders and a professor of psychiatry at John Hopkins University School of Medicine, she is also a professor of English at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. She is uniquely qualified to speak about both Lowell’s life-long struggle with bipolar disorder and his body of work as a poet.

Lowell was born on March 1, 1917 in Boston, Massachusetts. From a young age, Lowell felt compelled to be a writer, and not just any writer. He wanted to be a poet; THE poet. By all accounts, including those of his closest friends and family, he had a deep compulsion and drive inside him, one that strived for perfection and deeper thinking. Sadly, he also had inside him a disorder that would plague him for his entire life.

This disorder manifested itself in long periods of restlessness, sleeplessness, uncontrolled speech, physical violence, a brain that wouldn’t shut off, hyperactive libido, complete lack of inhibition, and a total dismissal of moral structure. When this ran its course, it was immediately followed by a long period of inactivity, exhaustion (physical and mental), and feelings of extreme guilt and self-loathing. For decades, this disorder went by the name of manic-depressive disorder. In 1980, the nomenclature was changed to “bipolar” disorder.

Lowell’s case was textbook bipolarism: prolonged periods of manic highs followed by near-suicidal lows. Over the years, Lowell learned to recognize the signs of oncoming mania, and his friends and family did as well. Oftentimes, he was able to check himself into hospitals for treatment. Occasionally, he was sent there against his will when his mania became too out of hand.

While his manic episodes were trying times for friends and family, Lowell found a way to at least take advantage of them. He wrote much of his poetry in mania-fueled marathon writing sessions. Many of these poems found their way into award-winning books, such as “Life Studies”, considered by many critics to be Lowell’s best book of poetry as well as a classic in 20th-century American literature.

It is amazing to think that Lowell, even through the roughest episodes of mania, managed to write some of his best work. It is, however, in the history of artistry and insanity, not unheard of or unusual.

Jamison writes about the growing scientific evidence that links positive mood increases with increases in creativity. Lowell’s experience with his manic episodes throughout his life seem to illustrate this and is supported by the scientific evidence.

When lithium was discovered to be highly effective in treating mania and depression, Lowell was an early beneficiary of the drug. It worked extremely well for him, and it helped keep his manic episodes at bay for longer periods of time. Sadly, though, it was not a cure. Lowell would suffer manic-depressive episodes for the rest of his life until his death on September 12, 1977. He died of a heart attack brought on by heart disease that most likely had its roots in his life-long struggle with bipolarism.

Jamison’s book is certainly an unusual biography in that it is a respectful account of a man’s life, but it isn’t only that. In many ways, it is a biographical account of Lowell’s illness and an examination and overview of the history of manic-depression/bipolar disorder.

Interspersed throughout the book are chapters that look at how mania and depression were treated by our ancients, starting as early as the Ancient Greeks, many of whom wrote about the connection between mania and creativity, madness and genius, long before the scientific evidence had been gathered to support it.

There is no doubt in Jamison’s mind that Lowell was a genius. There is also no doubt in her mind that Lowell faced his disease with aplomb, courage, and a realistic sense that he would never be cured so he may as well make the best of life, which is what he did.

Lowell’s life is, perhaps, a healthy template for people suffering from mental illness, in whatever form it takes but especially in the oft-misunderstood form of bipolarism. Jamison’s book is also an important, compassionate, knowledgable examination of mental illness in general, which is much needed in today’s hair-trigger, anti-intellectual, dispassionate atmosphere that has led to a complete lack of understanding and mistreatment (and, in many case, absolutely no treatment whatsoever) of the mentally ill. -

As Kay Redfield Jamison says, "This book is not a biography...[but]...a psychological account of the life and mind of Robert Lowell." In doing so, she does much to correct the negative views and reviews of Lowell, not least Ian Hamilton's biography of Lowell, first published in 1982, that presents an image of a boorish, angry man—no doubt gleaned from Hamilton's observations of Lowell in one of his late-stage manic episodes. Indeed, these manic episodes, followed by long periods of depression, were both the curse and source of inspiration throughout Lowell's life, intense periods when he wrote frantically and beautifully.

Jamison is a professor of mood disorders and psychiatry at Johns Hopkins university, and is supremely qualified to write about the nature, and terrible effects of Lowell's bipolarism (or, as she prefers, manic depression). She is also an honorary professor of English at St Andrews in Scotland, and this comes through in both her writing and sensitivity to Lowell and his work.

My only (slight) criticism is that, for readers more interested in Lowell's poetry, one does have to plow through long sections on mental illness, its historical treatment, and the latest views on its causes. This notwithstanding, it is a powerful and long-overdue book, particularly for those, like me, that adore Lowell's work -

My review of this book is now up at Literary Matters:

http://www.literarymatters.org/10-1-a...

And here are a few Lowell quotes from the book that I enjoyed and jotted down but was unable to work into the review, to tantalize you further:

"My disease, alas, gives one a headless heart...."

"Such a narrow fierceness, so many barbed quills hung with bits of skin."

"Why don't they ever say what I'd like them to say?...That I'm heartbreaking."

"To live a life is not to cross a field.... We cannot cross the field, only walk it."

"THE IMMORTAL IS SCRAPED

UNCONSENTING FROM THE MORTAL" -

Very excited about this one.

-

I thought this a beautifully rich and reverential book about the great American poet Robert Lowell. It's rich in its comprehensive investigation into his work and his manic-depressive illness and how the two affected each other. And it's finally an homage to the great poet he was despite his affliction. Kay Redfield Jamison makes clear early on that the book isn't biography. Rather, it's a psychological study of his life and mind and a history of his illness. Since his hospitalizations began in 1949 and he underwent 16 periods of treatment for his mania, the book is a record of his illness across his entire life as poet and teacher. There was no facet of his life not touched by the illness, no relationship not seared in some way. Though Jamison is a psychiatrist and not a literary critic, all her previously published work has involved the relationship of psychology and art. I think her knowledge of both fields are shown to good effect here. I was impressed with her discerning analyses of Lowell's poetry. Her glosses of the poetry don't have to concern themselves with the influence of his mania in order to show how adept she is as a critic. One of the things I like best about the book is what I think is her clear understanding of the man and poet Lowell was. In demonstrating how brave he was in the face of his lifelong disorder, she also demonstrates her evident respect and affection for him. This is a wonderful read.

-

Seventeen years ago I retired from my academic career as a scientist to immerse myself in poetry: in reading it, in writing it, and in studying it and poets.

Along the way I did encounter Robert Lowell and his poetry and specifically liked a couple of them: Skunk Hour and For The Union Dead. As for the poet himself I came away with the impression that he was a bit of an oddball, but no sense or perspective on what he contributed to poetry until I read Adam Kirsch's The Wounded Surgeon.

But I still had no appreciation of the full extent what he had done until I read this book. I came away with an entirely new perspective and at the end of the book I have three specific regrets:

---That I never got to meet this remarkable man

---That I was not there in June of 1960 when he read For The Union Dead on Boston Common

---That I was not there for any of his readings at Harvard College.

Now let me talk about this specific book. It is an extraordinary book about an extraordinary poet and written by an equally extraordinary author. Kay Redfield Jamison set out in this book to correct the record about Robert Lowell: to address and characterize his illness and its impact on his poetry and the field of poetry itself. To this task she brings several unique qualifications. In the first place she is a clinical expert, meaning her academic career has been devoted to the study of mood disorders, including manic depression, or what we now know as bipolar disease. Furthermore she brings the unique perspective of she herself suffering from bipolar disease. In addition, though she is not a poet herself, she writes like a poet: succinctness of writing, great metaphors, and magnificent lists, like this one:

"It seemed a uniquely blighted era of writers; manic breakdowns, depression, addiction, alcoholism, or suicide struck, among others, Hart Crane, Vachel Lindsay, Sara Teasdale, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Ezra Pound, Robert Frost, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Delmore Schwartz, Theodore Roethke, Randall Jarrell, Robert Lowell, Jane Kenyon, Boris Pasternak, Dylan Thomas, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, William Styron, Jean Stafford, James Schuyler, James Wright, Thom Gunn, Geoffrey Hill, Mary McCarthy, F. O. Matthiessen, Elizabeth Bishop, Edward Thomas, Virginia Woolf, Graham Greene, Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, John Berry“man, Anthony Hecht, William Carlos Williams, Walker Percy, Moss Hart, William Inge, George Mackay Brown, Louis MacNeice, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Edmund Wilson, Robert Penn Warren, Franz Wright, James Dickey, and William Meredith."

Several things about Lowell stand out from her story about him. In the first place, from the beginning he had an incredible sense of purpose, the sense that he was not only meant to be a poet, but that his purpose was to move poetry into new arenas. Secondly, is how much his mania was in the service of this purpose. Third, is an almost serendipitous occurrence which ensured he would achieve his purpose. His parents sought the help of a psychiatrist to cope with what they viewed as their wayward child, but this man, also a poet, had the incredible wisdom to get Lowell connected up with John Crowe Ransom and Alan Tate, two great poets and teachers. One wonders what would have happened to Lowell if he had not found this connection?

The other unique factor about Robert Lowell was that he had an iron willed determination – what he wanted and what he set out to do, he did. Jamison attributes this in part to his unique personality and equally to his New England Puritan legacy and character. More importantly she cited this will as essential, given the nature of his disease. He did not have garden-variety bipolar disease, his disease was so serious that he was hospitalized 20 times in his lifetime. And those hospitalizations were not just for a few days at a time and not just a few weeks---sometimes even for months. It took an incredibly strong will to overcome that amount of distraction and destruction, and he did it, to his credit.

She also observes how Lowell, toward the goal of achieving his stated purposes, changed his style, and poetry in general, with each book of poetry, not just once but multiple times, and his changes were seismic. The first example of this is the comparison of Lord Weary's Castle, 1944, to Life Studies, 1956.

Her academic research gives her another unique perspective, for she has focused on the relationships between creativity and bipolar disease, among other things. Her summation about creativity, writing, and mania is that mania drives the creativity in a man already skilled as a poet, but does not make a poet out of an uncreative person. Lowell himself affirmed in an interview that indeed his mania did drive his creativity and his poetry, more like the mania gave him the rough outlines and when the mania passed, with the cold eye of depression, he forged it into decent poetry.

Along the way, as she tells this clinical and poetic story, she also documents with comments from friends and acquaintances, what a warm and appreciated friend Robert Lowell was. Not the least of these friendships was the lifelong one with the poet Elizabeth Bishop, their correspondence documented in the book Words In Air. The point being not only was he a great poet but he was a great human and a loyal friend.

My humble opinion is this is not a book and a story to be missed by anyone with any interest in poetry whatsoever. -

"I have a nine-months' daughter,

young enough to be my granddaughter.

like the sun she rises in her flame-flamingo infants' wear."

---

"What can the dove of Jesus give

You now but wisdom, exile? Stand and live,

The dove has brought an olive branch to eat."

---

"When the Lord God formed man from the sea’s slime

And breathed into his face the breath of life,

And blue-lung’d combers lumbered to the kill.

The Lord survives the rainbow of His will."

THE ILLNESS AND INSIGHT OF ROBERT LOWELL

A new book is the first to bring clinical expertise to the poet’s case. What does it reveal about his work?

By Dan Chiasson

in:

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/201...

https://www.theparisreview.org/interv... -

I once had a college professor for a poetry class who believed that the explication of a poem should not involve the poet's life at all. She believed that when a poet wrote, he/she took on a "persona" that was not necessarily the poet. This book about the relationship between Robert Lowell's poetry and his bipolar disease blows up that theory. Lowell is his poetry. It's as much Robert Lowell as his nose. So. Dr. Hunt, you need to go back and rethink that grade you gave me for my Sylvia Plath composition.

I marked the rating lower because so much of it was repetitive. How many ways can one describe mania? -

Kay Redfield Jamison, a MacArthur Fellow and author of the standard text on manic-depressive illness and many other studies on the subject, begins her book by denying that she has written a biography. Since she is dealing with an individual and with the major episodes of his life, how is this not a biography? She does not say. But I presume she is thinking of biography as a chronological narrative that includes not just the major, but many of the minor details of a subject's life as part of a complete account. She does not say anything, really, about biography as a genre, except implicitly in her attack on Ian Hamilton's Lowell biography, which many of Lowell's friends, according to Jamison, dislike, and which she represents as having done a disservice to its subject

The brief against Hamilton is that he makes too much of Lowell's mental breakdowns and presents—especially toward the end of the poet's life, when Hamilton knew him—a condemnatory view of the man that injured Lowell's reputation. I was taken aback, since my impression, formed over many years, is that critics rank Hamilton's biography highly. How much a biography really damages its subject is debatable. Did Lawrence Thompson's Frost biography, often cited as a negative narrative, really do much, if anything, to diminish the poet's reputation? In a few cases, of course, a biography can injure––as with Rufus Griswold's malign life of Poe––but in the long run (and isn't that what counts?) skewed biographies are usually righted by better ones.

So l began with suspicions about Jamison. Was she inflating the need for another book on Lowell? So what if his friends did not like Hamilton's book? Such is often the case, for reasons I hope don't need to be spelled out in this review. I wondered if Jamison would simply repeat Joyce Carol Oates's tired thesis about biography as pathography, a low form of literature that dwells on the subject's frailties and follies. Then, too, I anticipated that this might be another one of those forays into biography by psychologists and psychiatrists bent on proving their theories through a procrustean study of a literary figure's life.

On almost all counts, I was mistaken. Re-reading Hamilton does expose the faults Jamison details. After reading Jamison, Hamilton does seem like an interloper, barging into Lowell's life to record the poet’s breakdowns with little understanding of manic depressive illness and the extent of Lowell’s responsiblity for his own actions. Reading Hamilton via Jamison, one can still laud many fine aspects of the former’s biography, his careful rendering of the circumstances of Lowell's life and literature, while realizing he simply does not have the knowledge required to understand Lowell's malady.

In Jamison, Lowell emerges as a tragic hero, in life and in literature, a noble man who caused considerable suffering, but one who persevered and earned the respect and affection of friends, including those he had abused during his manic states. The healthy Robert Lowell was a fearless, generous, and principled man and writer. Even with caustic friends like Randall Jarrell, Lowell remained loyal. He even invited Jarrell's fiercest criticism of his poetry. When Lowell relaxed his formalist, classical verse and brought on the disapprobation of Allen Tate, Lowell’s devotion to a mentor not waver. Literary life is full of thin-skinned writers who cannot abide criticism. Lowell set the opposite example.

In the course of a marriage that lasted two decades, Lowell was a trial to Elizabeth Hardwick, who emerges in Jamison's book as a heroine who could separate Lowell the lunatic (not too strong a word for a man who violently attacked his first wife, Jean Stafford, broke her nose, and assaulted many others, including the police) from the peace loving, honorable individual who was also a conscientious objector.. Lowell wore her out eventually, but she never doubted his genius or his decency. Jamison shows why. Remorseful about his manic periods, when he also verbally attacked friends and family, Lowell realized he was in the grip of compulsions that sooner or later would lead to depression and the search for treatment. Lithium eventually brought him some respite but no cure, since getting the dose right was tricky and sometimes led to toxicity and times when Lowell had to be hospitalized owing to his reliance on the drug. But he never stopped trying to get the right therapy or reckoning with the harm he had caused.

Jamison treats Lowell's manic-depressive illness as a lifelong problem connected to his creativity. She does not argue that the manic periods are what produced great poetry, but she does consider the possibility that without the onset of mania Lowell might not have written his best verse. She cites numerous studies of the connection between mania and creativity, while noting, of course, that mania per se does not cause or even lead to great art. But people in the manic state do often feel creative, and there is a case to be made for writing as a kind of manic activity even if the writer does not suffer from manic-depressive disease. Jamison never forgets the peculiarities of Lowell's case: He might write stirring first drafts in a manic state, but if that state became prolonged, the poetry would deteriorate. In the downward depressive part of his psychic cycle, Lowell often became a superb critic of his first drafts, fashioning poems that, in the end, were far superior to his exuberantly written first lines.

My one reservation about Jamison's approach is that it is redundant. She repeatedly emphasizes how bravely Lowell confronted his demons, his great discipline in working through his upsets, and his courage in seeking out new styles and forms of expression. Every round of his manic-depressive disorder calls for another round of encomiums, as if Jamison is urging her patient on. But it would not be fair to say her book is thesis-ridden. On the contrary, in citing so many studies of manic-depressive illness, she reveals how complex a matter it is to bring the weight of scientific literature to bear on an individual's life. And by doing so, she is providing a cautionary note to biographers. We cannot ignore the role psychology plays in our subjects' lives, but we also cannot suppose a certain psychological approach will be dispositive.

Even the term manic-depressive, Jamison explains, is debatable. Some clinicians prefer bi-polar as a more comprehensive term, although Jamison thinks using bi-polar obscures or neutralizes the devastating aspects of the disease. The psychology she employs is very much a work-in-progress, and so she is right to report Elizabeth Hardwick's skepticism about the doctors who thought they could cure her husband. Toward the end of his life, at sixty, Lowell seemed to realize no cure was possible, but he never despaired, never stopped looking for equilibrium. He feared, though, that his heart would give out. And that is just what happened. -

My enjoyment of this book is due in part to the fact that it's not by a literary scholar. As a history of Robert Lowell's mind, written with great sympathy by a fellow sufferer, it's the book I think Lowell has deserved all along, and I hope it goes some way toward reviving his reputation. Here are two paragraphs that give a sense both of Jamison's style and of what the book is about:

When mania swept through Robert Lowell's brain it did not enter unoccupied space. It came into dense territory, thick with learning, metaphor, and history; filled with the language and images of Virgil and Homer, the violent rhythms of Nantucket whaling; a decaying Puritan burial ground stacked with ancestors and ambiguity; the words and moods of New England writers, Hawthorne and Melville, Emerson, Thoreau, and Henry Adams, Jonathan Edwards; and the thicket of memories kept by a sensitive and observant child reeling within his family. The words of Dante, Shakespeare, Pasternak, Hardy, and Milton were not just in his mind but were his mind, kept alongside the place he kept for Dutch paintings and Beethoven's late quartets. Lowell's mind had been stamped by words and shaped by shifting moods; always, it had been beholden to words. Mania, when it came, shook his memory as a child shakes a snow globe.

When Lowell was well, which was most of the time, his mind was fast, compound, legendary. The depth of his knowledge and the relentless seriousness with which he acquired and used it were spoken to by virtually all who knew or studied with him. His was a retentive and elaborating mind; brilliant, all encompassing; a labyrinth of myth and language and experience. When mania attacked it advanced on a well-used and comprehended library of history and life, a field of ideas that could not be crossed. Mania attacked in the way characteristic of mania, a stereotypic assault, but the brain it set afire was rare in its capacity, seriousness, and discipline. (p. 282) -

A fascinating book by an author who has written widely on bi-polar illness, from which Robert Lowell suffered. Interestingly, she does not identify herself as someone with bi-polar illness, though her earliest work was about her psychological struggles and successes. (Or if she did, I didn't see the reference.) Lowell was a powerful and successful poet (Pulitzer Prize twice) who was hospitalized numerous times while suffering from mania. He then returned home depressed and had to repair relationships he had severely damaged when ill. The family history of this deeply American and New England poet was quite interesting to me. But Jamison follows his medical "career" closely, sometimes much too closely. With much too much information on manic depression/bi-polar illness - historical, in literature. This detracted from the powerfully told story of an immensely talented and prolific poet, well loved by many people, despite his serious illness.

-

Robert Lowell was a Pulitzer prize winning poet, extremely bright and he suffered from bipolar illness / manic depression. Jamison does an amazing job of taking us inside the life , from birth to death, of someone who is brilliant, creative and suffers from a major mental illness. She makes an exhaustive examination of the connection between mania and creativity. I have read other books by Jamison, in particular, The Unquiet Mind, in which Jamison writes about her own journey with bipolar illness and her works as a clinical psychologist. While these books may not be for everyone, I must stress that neither are dry clinical treatises, but beautifully written stories and journeys into the life of mental illness, profound efforts to help the world better understand mental illness.

-

A profoundly affecting, if also rather relentlessly bleak study of Robert Lowell's life and art through the prism of his lifelong struggle with mental illness. The only criticisms I would offer are that the catalog of breakdowns involving trips to medical facilities becomes quite relentless, and there is a lack of any sustained readings of the poems that might capture the vacillations and oscillations of mania and depression. But in general, this is a very worthwhile addition to the body of work around Lowell and a welcome corrective to the Ian Hamilton biography.

-

An outstanding book that brings us closer to Robert Lowell’s life and work than any previous book on him—or, indeed, on any other poet. Jamison brings her unique perspective and intimate understanding of how mental illness (unlike most physical illness) is misperceived as willful, a character flaw, a thing to be ashamed of. In this great poet and in so many other artists, as Jamison convincingly demonstrates, such illness is part and parcel of the creative spirit and can help enable extraordinary accomplishment, while at the same time be destructive to human connection and therefore uniquely lonely to endure. Lowell’s courage and resilience in the face of repeated hospitalizations and mental breaks is as remarkable as the poems he wrote despite (and perhaps because of) his illness.

-

Another excellent examination by K Redfield Jamison of the association between bipolar disorder or manic-depression, which she prefers to call it, through the eyes and writings of the poet, Robert Lowell. Although repetitive at times and thus too long, she writes an engaging narrative of Lowell's life weaving through it how his manic depression influenced his writings and familial relations. Last chapter on mortality beautifully articulated.

-

Kay Redfield Jamison forever, tbh

-

a heartbreaking and poignant portrait

-

Recently discussing my poetry with my mother-in-law, an English teacher and writer herself, I confided in the difficulties I face trying to steal a few minutes here or there from work or family life to compose. I must have touched a nerve--for the next several minutes she inveighed upon my gender’s privilege in this department. I supposed I’m assigned to read A Room of One’s Own.

Such is the climate today, in the most private of circumstances or the most public. For most of human history, a vast majority faced categorical obstacles that made most high forms of cultural participation rare or impossible, thanks to prejudices against gender, race, sexuality, religion, or class. A few hundred years ago, on my mother’s side, I would have been a Jew living in a Bohemian ghetto. On my father’s side, I would have been a semi-illiterate skilled laborer. So much for poetry.

The English tradition of verse is a gentleman’s tradition in which the poet is usually male, Anglican, classically educated, and at leisure to pursue his craft in an unhurried manner. Topics should reverberate with special knowledge that can only be acquired with access to great libraries and sympathetic mentors.

One could not find a better 20th-century American inheritor of that tradition than Robert Lowell. Boston Brahmin through and through, Lowell had every advantage imaginable to the aspiring poet: wealth, connections, and consummate access to exclusive education, institutions and people. On top of that he was a man; a tall, fit, and handsome one at that. His I.Q. held him safely beyond average. His parents were far from perfect, his mother especially problematic, but they provided for him and ultimately granted him the freedom and support to pursue his vocation. Lowell lived to see himself widely regarded as the greatest American poet of his generation, and while that claim can still credibly be made today, it’s much more difficult (Langston Hughes and Elizabeth Bishop come to mind). That his life deserves another biological appraisal is entirely reasonable; Ian Hamilton’s 1982 authorized biography has not aged well.

Lowell did suffer from one serious obstacle, however. He was occasionally raving mad. In her new book, Robert Lowell, Setting the River on Fire: A Study of Genius, Mania, and Character, Dr. Kay Redfield Jamison focuses on Lowell’s bipolar disorder. While long-winded and apt to repeat herself (she could have benefited from a better editor), Jamison is deserving of the praise she has received for this volume. A psychiatrist and author; her literary expertise and skill at research are also fully up to the task. She clearly is steeped in Lowell and his writing and is able to track and cite his broad influences fluently. More forgiving of Lowell than Hamilton’s dishy and unsympathetic official biography, one gets the feeling for Jamison, it’s not enough that Lowell’s poetry is now and will likely always be celebrated. She needs to save his reputation as a husband, father, mentor, and friend.

With respect to his poetry, to be sure, madness was not entirely Lowell’s obstacle. Jamison makes that abundantly clear. Bouts of mania granted him superhuman levels of confidence, creativity, and endurance before spinning out of his control. Jamison carefully details Lowell’s ancestry and childhood, but softpedals its benefits. She doesn’t question why his illness didn’t make him an pariah, and is reluctant to describe the marketing advantages of playboy/badboy/madman for selling books, filling lecture halls, and securing lofty and rewarding fellowships. Yes, we get the smashed furniture, affairs with students, unwanted sexual advances, verbal bullying, threatened colleagues, and claiming to be Jesus Christ--naked. But Lowell was never beaten up by cops and never faced charges for his actions. Like those of his time, Jamison is quick to forgive him. He certainly livened up the faculty club.

Jamison exactingly chronicles Lowell’s many lost years of his 60 total to institutionalization. She pours over his medical records and excerpts his doctor’s notes. (Hamilton does not, and thus misses much). While he had periods of calm, Lowell and his family (three successive wives, two biological children) could never predict when the next breakdown would occur. Jamison documents how they lived in fear and on edge. Yet Lowell produced over a dozen books of original poetry, translations, and plays in his lifetime, most bearing an unhurried manner and a panoramic position from which he viewed the Western poetic project. Unlike his friend, fellow poet, and depressive John Berryman, Lowell died of natural causes.

The glamour of a poet is easy to fall for. From the outside, it’s pretty ideal. Unlike working for someone else, you set your own schedule. Nobody to report to. If you want to teach you may; students likely idealize you. Your writing cannot be “right” or “wrong”, you merely must be interesting. Living in a world of fantasy is actively encouraged. Unlike a novelist there’s less paperwork. Travel is welcome. Smart dress is a must. The parties are smashing.

Assuming the financial problems can be surmounted through grants, teaching, and inheritance, other problems remain. Most of humanity operates on a schedule. Waking and sleeping times are fixed, as are meals and commutes. Not so for the poet. The poet, unless he imposes a schedule upon himself is just as likely to write at midnight as he is midday. The work follows the poet around, waking or sleeping, eating, cleaning, walking, driving, fucking. It’s barely an overstatement to say mood disorders and alcoholism are occupational hazards; to me it’s obvious Lowell’s vocation aggravated his disease. Combined with the creative advantage mania conferred, Lowell’s chosen life path invited crack-up. Jamison clearly thinks otherwise. She minimizes Lowell’s tendencies to indulge himself and instead is inclined to find therapeutic effects in his writing. The question may be academic. Lowell was going to write poetry whether it made him crazy or not.

Lowell’s illness is part of his art and inseparable from it. While it’s likely he would have been happier without his disease, it’s unlikely he would have produced the quantity or quality of work without it. Nobody should envy Lowell. Yet Jamison goes too for in tying Lowell’s greatness to his courage in fighting bipolar disorder. She expends whole chapters on Lowell’s bravery, developing his obsession with military history into a comparison to battlefield valor. At one point she equates Lowell’s heroism to poet and decorated World War One veteran Siegfried Sassoon. While I’m in no way discounting Lowell’s willpower in the face of a brutal and disfiguring disease of the mind, I find Jamison complicit in a cult of Lowell aggrandizement--a cult Lowell himself deliberately conceived. Lowell went into battle only for Lowell, with a mercenary instinct for self-promotion. He did not want to be a mere survivor, for that would hardly suffice. Even when not manic, Lowell unguardedly articulated his desire to be remembered on the scale of a Milton or Napoleon, two men he idolized yet saw as rivals. Publicly and privately, Lowell could never contain his self-regard. While it is not his fault he was born into a deeply uneven playing field, there is no evidence he did anything but take advantage of it. To put it in the lingo, Lowell couldn’t check his privilege. If Hamilton’s earlier biography questions Lowell’s character, Jamison cannot so easily repair it.

While it’s not unusual for famous men to treat women poorly, we should not be in the habit of forgiving it. Jamison strains mightily to portray Lowell’s three wives and various lovers as respected collaborators who harbored little or no resentment over their treatment. But the historical record suggests otherwise. Lowell famously excerpted, paraphrased, and rewrote his second wife’s letters to him in his collection of poems airing the dirty laundry of their divorce. While Elizabeth Hardwick understood Lowell better than perhaps anyone else, she knew she had been profoundly mistreated. But besides the brave and brilliant Adrienne Rich, the cowardly cozy literary world was reluctant to go on the record against the sexual entitlements of its reigning king.

To quote another celebrated American poet, the times they are a-changing. Today we are ourselves on fire over matters of privilege. Robert Traill Spence Lowell IV was never anxious putting his name on a cover letter, but today names like his are less assured. Universities, publishing houses, and grant-giving institutions are attempting to pivot away from their reflexive awe at the superficial elements of the English tradition, and in doing so often cling to something else equally superficial: identity. We know now that a poem can be English without needing to be Christian, steeped in classical themes, and catering to an affluent male ear--all of which could describe a Lowell poem. But let’s not throw out the baby with the bathwater. At the heart of good English is an awareness of the language as testament both to past and present. English appropriates culture; it’s a mutt language bent on digging up other languages’ bones.

Flawed as he is, Lowell is an exemplar, his poems a living, breathing philology. Finding poets publishing today approaching his level of craft is simply impossible; Lowell was a master of both rhymed and free forms, and his poems could succeed despite his often awkward conceit and turgid allusion through his richness of meter, surgical phrasing, and percussive consonance. Lowell also knew by exploring English’s prior uses while inventing new contexts through his witness, his poems could achieve lasting erudition. He does this so consistently in his work that it’s as if he hails not just from another era, but an entirely different civilization. Though his age’s prejudices still seem right next door.

Ultimately Jamison’s goal is not to judge Lowell but to understand how he lived and endured his mental illness in order to address his monstrous life ambition. In doing so she loses objectivity but gains insight. Which is largely a laudable enterprise. Readers of poetry may be familiar with her conundrum: to really enter into the world of a poet, one must be willing to empathize. Today, more so than perhaps any other time, it is difficult yet necessary to do so. -

3.5 rounded up to 4.

There was something so beautifully empathetic about this book. It is hard when writing about someone who struggled so much with their mental health and died relatively young not to write tragedy, but Jamison managed to help me see why people like (my faves) Elizabeth Hardwick and Elizabeth Bishop loved Lowell so dearly. In our current media landscape, I can only imagine how the culture would have treated Robert Lowell after each experience of mania. One only has to look at the public mental health crises of public figures to see how visible harm, madness, and humiliation hide the private suffering that underlies mental illness. This book managed to acknowledge the harm Lowell did, the suffering and lack of control that caused him to harm, the courage he had in facing the aftermath of his actions, and the person he was outside of his worst periods of mental illness. It asked questions I ask myself every day in my work--namely: How much responsibility can we place upon those who are not in control of their actions? Can we judge someone's character on what they do during mania? How do we discuss the relationship between mental illness, art, and intelligence in ways that do not romanticize or place moral judgments on suffering?

Still, I have some problems with the book. As someone from a social work and psychoanalytic background, I found the extensive discussion of Lowell's genetics and family history as a cause of his manic-depression compelling and interesting, but rather reductive. I found it a rather glaring omission that she never explicitly connected at least the severity of Lowell's mental illness to the negligence he experienced from his parents (and, specifically, his mother) as a child. I also struggle generally with conversations about IQ and manic-depression independent of any discussion of IQ and diagnosis as methodologically complicated. Finally, the last chapter was out of place in the rest of the book. Connecting Robert Lowell's legacy and broader family legacy to the history of racial justice in New England was reductive and idealizing in a book that largely stayed in the realm of nuance. Given the rosy depictions of New England in the earlier part of the book, I felt like Jamison was compelled to add this in as a perfunctory disclaimer for the largely depoliticized discussion of Lowell's Pilgrim and Puritan ancestors in the first part of the book. -

Kay Jamison has yet again written a true look into the life of a Bipolar. Her knowledge and own personal experience with Bipolar come through with intelligence and compassion. This book is a window into Robert Lowells's life with Bipolar Disorder. From childhood until his death you get a look into his home life, creativity, and struggle with his illness. Beginning in his childhood with his never ending effort to satisfy his parents. Telling the reader about his own conflict with understanding his diagnosis to his parents denial and even a background into the heredity pattern of the illness. Robert's personal poems, notes, and journals tell a broader story, one that follows him through his entire life. You hear of the many loves and loves lost and even see correspondence between them. There are also letters from many friends and colleges that show the compassion and patience his friends have during some of Lowell's worst episodes. The journals and letters from his hospitalizations show the darker more ill side of Lowell. As you read the book you begin to see the pattern of Bipolar and how it affects the sufferer. You ride the wave with Lowell so to speak. The ups and downs come through, the fear, guilt and shame that follow after an episode, the moments of lucidity and peace, the pain and suffering involved in finding proper treatment, and how a mentally ill mind works and sometimes malfunctions. You gain a form of intimacy with Lowell as you read this book. It is like you are there with him as he writes his letters and documents his life. It gives you an understanding of his writing, his heart and the passion that inspired. A beautiful, intelligent, and educating book! I highly recommend this to any reader of Robert Lowell or to anyone who struggles with mental illness.

-

There is a lot to like in this book, and it helps to correct the very negative views of Lowell in some biography and criticism. Much can be forgiven to madness, though not Lowell's dumping his second wife (of two decades) and their daughter to marry an alcoholic heiress near his life's early (age 60) end. Jamison seems very much a fan of Lowell, but even she can't quite make this huge error look anything but monstrous. This isn't quite a biography; biographical detail would fight with the hagiographic elements of Jamison's book.

Still, while rambling and in need of a better editor, the book is impressive, particularly in its evocation of the particularly New England aspects of Lowell, of his debt to his time, to place, and also to history and to literary history.

That Jamison quotes generously from Lowell's poetry will help make the book accessible even to a reader not very familiar with his work. Her ending, which juxtaposes Lowell's death and funeral with a reading of "For the Union Dead" is particularly impressive and likely to be of use to those coming for the first time to Lowell.

In his New Yorker review, Dan Chiasson wrote, "Jamison’s study tells us a lot about bipolar disorder, but it can’t quite connect the dots to Lowell’s work. Poetry doesn’t coöperate much with clinical diagnosis." That is probably the book's flaw in conception; still, clinical diagnosis does help us see and understand a lot. -

I have very mixed feelings about this title. First, let me say I'm a long-time fan of Lowell's poetry, and I'm interested in its connection to his manic depression. So I was excited that an author who writes in such a distinguished way about mental illness was taking him up as a subject.

But I don't think this book is a total success. It's very good at explicating the nature of manic depression, its treatment in Lowell's lifetime, and it's horrible effects on his art and his relationships. Still, at the end of the book, I'm left wondering about the parts of Lowell that were not about his mental illness and how that influenced his work, and I don't think that story comes through very clearly here.

The chronology of the book is meandering, moving from start to finish generally, but doubling back on itself at times. That became kind of tiresome. There are many quotes from Lowell's poems here, but I don't think I would have the sense of his work and his themes beyond mania from what is included. There's a danger of conflating an author entirely with his or her poems, and even in someone whose writing is as autobiographical as Lowell's there are other ideas in play. -

Wow! this book is a major oeurve, and an enlightening glimpse at the relationship between art and mania. Jamison examines Robert Lowell’s life and work, with reference to the literary and historical figures which influenced him, and traces his artistic development concurrently with his manic-depressive condition. While never denying the havoc it wrecked on his own life and the lives of those who loved him, Jamison credibly presents a link between creativity at the very high end of the spectrum and the experience of manic episodes. Illustrating how Lowell’s aritistic development and the evolution of his poetic style were bookended by his frequent hospitalizations, she also gives a powerfully positive view of Lowell’s character, as he persevered despite his illness, and continued to work through the disruptions it caused. This is an illuminating book for anyone interested in either poetry (or any other art form) and/or mental health. Although bipolar disorder, as it is called today, is still devastating, it is somewhat encouraging to see how far treatment modalities have come, although they still have far to go.

-

This was a enlightening, frustrating and often dark journey on Robert Lowell’s genius and struggle with his severe bipolar disorder. His mania led to beautiful and intuitive work but at such a high cost to himself and those who loved him or tried to love him.

Knowing that manic wave, albeit with less intensity when everything connects to everything and all the questions seem answerable and creation is everywhere if only you could express it. If only there was enough time. The cohesion, so put together in the mind often jumbles out of the mouth. The fluidity inside fragments as it touches air. It’s contagious and exhausting and it leads to unbelievable heights, energy, danger, promiscuity, unmatched love, passion, inspiration.

Lowel was able to discipline himself and channel it into his prolific writing but it took a toll on him and his surrounding universe.

The opposite can be dark filled with excess reflection, remorse, shame, solitude and can often overshadow whatever fruits were bared.

This was a heavy book that was less biographical and more a character study of one of America’s greatest poets. -

I've always wanted to learn more about Robert Lowell. I don't know why specifically. I've heard the name, knew the basic "bullet points" on him. The great poet, manic depressive, Bostonian...etc. When I saw this book was coming out I figured here was a perfect opportunity to learn that and more. I was blown away. Not only by the writing, that was phenomenal, but in Lowell. How a person so revered in a field could continue to be successful while bearing this burden on his psyche was incredible. Kay Redfield Jamison, or Dr I should say (I didn't accredit that to her only because the title page didn't) does a phenomenal job telling us about the disease as much as the man/poet. How one effected the other. Really incredible stuff. Thanks to her for delving into the mania that was Robert Lowell. Allen Ginsberg said it best, "I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked..."