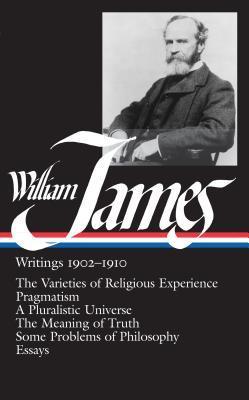

| Title | : | Writings 1902-1910: The Varieties of Religious Experience / Pragmatism / A Pluralistic Universe / The Meaning of Truth / Some Problems of Philosophy / Essays |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0940450380 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780940450387 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 1379 |

| Publication | : | First published February 1, 1988 |

In The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) James explores “the very inner citadel of human life” by focusing on intensely religious individuals of different cultures and eras. With insight, compassion, and open-mindedness, he examines and assesses their beliefs, seeking to measure religion’s value by its contributions to individual human lives.

In Pragmatism (1907) James suggests that the conflicting metaphysical positions of “tender-minded” rationalism and “tough-minded” empiricism be judged by examining their actual consequences. Philosophy, James argues, should free itself from unexamined principles and closed systems and confront reality with complete openness.

In A Pluralistic Universe (1909) James rejects the concept of the absolute and calls on philosophers to respond to “the real concrete sensible flux of life.” Through his discussion of Kant, Hegel, Henri Bergson, and religion, James explores a universe viewed not as an abstract “block” but as a rich “manyness-in-oneness,” full of independent yet connected events.

The Meaning of Truth (1909) is a polemical collection of essays asserting that ideas are made true not by inherent qualities but by events. James delights in intellectual combat, stating his positions with vigor while remaining open to opposing ideas.

Some Problems of Philosophy (1910) was intended by James to serve both as a historical overview of metaphysics and as a systematic statement of his philosophical beliefs. Though unfinished at his death, it fully demonstrates the psychological insight and literary vividness James brought to philosophy.

Among the essays included are the anti-imperialist “Address on the Philippine Question,” “On Some Mental Effects of the Earthquake,” a candid personal account of the 1906 California disaster, and “The Moral Equivalent of War,” a call for the redirection of martial energies to peaceful ends, as well as essays on Emerson, the role of university in intellectual life, and psychic research.

Writings 1902-1910: The Varieties of Religious Experience / Pragmatism / A Pluralistic Universe / The Meaning of Truth / Some Problems of Philosophy / Essays Reviews

-

William James In The Library Of America -- II

The great philosopher and psychologist William James (1842 -- 1910) is best-known as the founder, with C.S. Peirce and John Dewey, of the distinctively American philosophy of pragmatism. James is that indeed, but he is much more as well. This volume of the Library of America series consists of five books and nineteen essays by James written between 1902 and 1910. (A separate Library of America volume includes James's earlier writing, including "Psychology, A Briefer Course" and the essay "The Will to Believe".) The volume will give the reader a feeling for the breadth of James's philosophical, scientific, and religious concerns. The volume is edited by Professor Bruce Kuklick of the University of Pennsylvania who has written extensively about James and about the history of American philosophy. In this volume, Kuklick provides an unusually thorough chronology of James's life to accompany James's texts.

For those readers with no prior familiarity with James, I suggest beginning with a brief essay "Answers to a Questionniare" (p. 1183) that James wrote in response to questions from a colleague at Harvard about the role of religion in life. In his answers, James briefly summarizes his theism and his conviction of the value of religious experience. He writes that "Religion means primarily a universe of spiritual relations surrounding the earthly practical ones, not merely relations of 'value,' but agencies and their activities". James says that his belief in immortality had increased over the years as he is "just getting fit to live." As to the authority of the Bible, James states that it is not his authority in religious matters. Rather, he describes it is "so human a book that I don't see how belief in its divine authorship can survive the reading of it."

This short questionnaire response provides a wedge into the over 1300 pages of text in this volume. James was trained as a physician and a scientist and was greatly impatient with what he viewed as philosophical abstractions. Yet religious concerns were at the heart of his thinking. James undertook the traditional philosophic attempt to reconcile the teachings of science with those of religion. His famous teaching of pragmatism was, as he stated in the first chapter of his book "Pragmatism" designed to do so. Other philosophical positions that James developed, including radical empiricism, pluralism, and meliorism were designed to honor the importance of human feeling and effort and to emphasize the large role of the spiritual in human life.

James long had the ambition of writing a systematic exposition of his philosophy in a book, but he never did. (His final book, "Some Problems of Philosophy", published after his death was an attempt to do so, but it was left incomplete and sketchy. It is included in this volume). Thus, with the exception of "Some Problems" the books included in this collection are series of lectures that James delivered over the course of the years. They are beautifully written and aimed for the most part at an audience of non-specialists. But, on the whole, the books consist more of suggestions and of paths for exploration than of detailed philosophical argumentation. Reading the books in this volume will show the reader how James's thought changed and developed over the years.

The first book in the volume, "The Varieties of Religious Experience" consists of the Gifford Lectures James delivered in Scotland at the turn of the Twentieth Century. The "Varieties" is still my favorite James book, with its unique combination of psychology and philosophy, as James attempt to explain the value of the religious life by describing the forms it takes in the lives of individuals from many times and places.

Probably the most famous single work of American philosophy was James's "Pragmatism" which again consists of a series of lectures delivered in New York City and Boston. In this book, James made high claims for the importance of philosophy and developed pragmatism as a method and as a philosophical theory of truth. In a subsequent book called "The Meaning of Truth", James gathered together thirteen of his essays, in addition to a Preface and two new essays, to try to explain in greater detail his theory of pragmatism and to answer objections to it. The "Meaning of Truth" is James's most difficult and technically dense book.

In his final book of lectures, "A Pluralistic Universe" James's thought turned in new and more speculative directions. The book continues James's longstanding attack on the absolute idealism, derived from Hegel, which was still preeminent in his day. James develops a philosophy he calls radical empiricism derived in part from the French philosopher Henri Bergson and in part from the German thinker Gustav Fechner. The book places limitations of the value of conceptual, scientific thinking looking instead to the stream of experience and the flow of human consciousness. In this book, James engages in speculative philosophy, adopts a form of idealism almost in spite of himself, and goes far beyond the pragmatism of "Pragmatism" and "A Theory of Truth". This book is James's fullest statement of his thought, and it does not always get the study it deserves.

As I mentioned, James left his final book, "Some Problems of Philosophy" incomplete, but what we have of it is a valuable complement to "A Pluralistic Universe." The essays in this volume cover a variety of topics, philosophical, psychological and otherwise, and, with the brief response to a questionnaire I mentioned at the outset of this review, provide a good approach to the longer works. I tend to like the more popularly-oriented of the essays, especially the great essay James wrote on "The Moral Equivalent of War." Again, this is an essay that newcomers to James need to read. The essay on "The True Harvard" has moving things to say about the intellectual life, and the "Address at the Centenary of Ralph Waldo Emerson" is a fitting tribute to its subject.

There is much to think and reflect about in this compilation of William James's later writings. His philosophy still has much to teach.

Robin Friedman -

Assigned in class in 1993, I have finally completed reading William James' The Varieties of Religious Experience. Upon beginning the book a few months ago, I posted a confession about my never having read it in class at the time nor after, despite its central importance in my philosophic worldview, profession, etc. Here's that confession:

http://escottjones.typepad.com/myques...

James does something which still seems vital more than a century later. A thoroughly educated progressive, he takes religious experience seriously. Oh, he criticizes much about it, particularly the particulars of various sick-minded and weak souled folk. But he does not count their experiences as less than genuine or authentic and, while criticizing, treats them with respect. He believes that religious experience can be approached scientifically and that objective truths can be formulated. Though, ultimately, it is the subjective experiences that matter most.

At times one must skim quickly through the book, but one must also slow down to appreciate his literary skill and his witty remarks. More than once I found myself guffawing at some comment he makes (these were originally lectures). This guffawing at a philosophy lecture must reveal my geekiness.

James' generosity of spirit concludes the book with where he thinks religion is headed, and by-and-large he was correct. A greater pluralism, an openness, a focus on love and action, a less-dogmatic spirituality.

For James the basic principle is does religion work, does it bear fruit, and it is from this standpoint that he criticizes the extremes. In 2012 we would do well to continue learning from James. -

James is one of the greatest American minds. He was a thinker ahead of his time--a postmodern thinker before postmodernism (a prepostmodern?). You'll do well to spend some time with William James.

-

The Varieties of Religious Experience and Pragmatism are superb, but the remaining material mainly serves as an apology for these two books. Definitely interesting, but do we really need 1300+ pages?

My favorite section of Varieties is actually a footnote that quotes a letter a philosopher at Amherst wrote to James:

Mr. Blood and I agree that the revelation is, if anything, non-emotional. It is utterly flat. It is, as Mr. Blood says, 'the one sole and sufficient insight why, or not why, but how, the present is pushed on by the past, and sucked forward by the vacuity of the future. Its inevitableness defeats all attempts at stopping or accounting for it. It is all precedence and presupposition, and questioning is in regard to it forever too late. It is an initiation of the past.' The real secret would be the formula by which the 'now' keeps exfoliating out of itself, yet never escapes. What is it, indeed, that keeps existence exfoliating? The formal being of anything, the logical definition of it, is static. For mere logic every question contains its own answer -- we simply fill the hole with the dirt we dug out. Why are twice two four? Because, in fact, four is twice two. Thus logic finds in life no propulsion, only a momentum. It goes because it is a-going. But the revelation adds: it goes because it is and was a-going. You walk, as it were, round yourself in the revelation. Ordinary philosophy is like a hound hunting his own trail. The more he hunts the farther he has to go, and his nose never catches up with his heels, because it is forever ahead of them. So the present is already a foregone conclusion, and I am ever too late to understand it. But at the moment of recovery from anaesthesis, just then, before starting on life, I catch, so to speak, a glimpse of my heels, a glimpse of the eternal process just in the act of starting. The truth is that we travel on a journey that was accomplished before we set out; and the real end of philosophy is accomplished, not when we arrive at, but when we remain in our destination (being already there), -- which may occur vicariously in this life when we cease our intellectual questioning. That is why there is a smile upon the face of the revelation, as we view it. It tells us that we are forever half a second too late -- that's all. 'You could kiss your own lips, and have all the fun to yourself,' it says, if you only knew the trick. It would be perfectly easy if they would just stay there till you got round to them. Why don't you manage it somehow? -

Specifically looked at "The Meaning of Truth". W.J. spent many words on many pages to say things like 'it depends' and 'it changes' and 'too many people have too many different ideas about it'.

-

Undoubtedly William James most popular book, I found this to be, as it always is with James, a joy to read. His style kept me going when both the combination strange ideas and impenetrable prose of his cited examples retarded my progress. His focus on the individuality of experience was what struck me as central and certainly most important to me - the mature individualist that I am. While I was not convinced by the mysticism surveyed or the various rationalizations of religious pondering, I came away with a better sense of this type of thought. Unlike Santayana I was not bothered by the focus on "religious disease" or "sick souls", but my perspective, unlike his, is a bit more rational, if not more reasonable. On the whole a very good book about a subject that is spiritual in many ways.

-

Much more there to return to, but his admiration for Bergson is my touchstone. If scientists and philosophers want to return to working on problems defined by their degree of consequence to the living world, then James' work will be of great value to them.

-

I think I'm gonna return to William James a lot in my academic papers specially The Varieties of Religious Experience and Pragmatism!