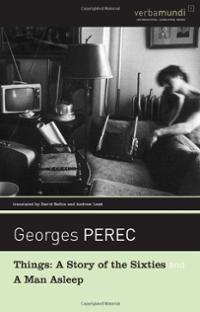

| Title | : | Things: A Story of the Sixties / A Man Asleep |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1567921574 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781567921571 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 221 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1965 |

Jerome and Sylvie, the young, upwardly mobile couple in Things, lust for the good life. "They wanted life's enjoyment, but all around them enjoyment was equated with ownership." Surrounded by Paris's tantalizing exclusive boutiques, they exist in a paralyzing vacuum of frustration, caught between the fantasy of "the film they would have liked to live" and the reality of life's daily mundanities.

In direct contrast with Jerome and Sylvie's cravings, the nameless student in A Man Asleep attempts to purify himself entirely of material desires and ambition. He longs "to want nothing. Just to wait, until there is nothing left to wait for. Just to wander, and to sleep." Yearning to exist on neutral ground as "a blessed parenthesis," he discovers that this wish is by its very nature a defeat.

Accessible, sobering, and deeply involving, each novel distills Perec's unerring grasp of the human condition as well as displaying his rare comic talent. His generosity of observation is both detached and compassionate.

Things: A Story of the Sixties / A Man Asleep Reviews

-

Things: A Story of the Sixties predates all those tiresome novels about corporate-culture ennui, Ballardian death of affect, and dehumanisation through advertising and leaves them weeping into their MaxPower V9 toasters-cum-dildos. What a heartbreaking and beautiful novella! Oh Georges, is it really so sad? Perec narrates from a distance, leaving his characters Sylvie and Jérôme to fumble through a blank lower bourgeois existence, besotted with appliances and desperate to shimmy up the ladder without accepting their place as adults. By piling up descriptions, razor-sharp character analysis and cultural scene-setting, Perec captures the painful loneliness of upwardly mobile corporate life—his writing glitters with perfect, wrenching subtlety and humour. Oh Georges, Georges, Georges! And then there’s A Man Asleep, a beautiful exploration of complete disengagement from the culture, written in energetic second-person prose, chock with penetrating insights into man’s desire to escape the terror and horror of everyday life. An absolutely magnificent duo of novellas—epochal, strange and powerful.

-

This book brings together two early novellas by Georges Perec, who is best known for

Life: A User's Manual. In both cases these are strong on concept and rather weak in characterisation. These are not easy stories to review, and neither is essential to understanding Perec, so I'll just write a few brief notes.

Things follows a Parisian couple in their 20s and explores the way their lives are determined by material possessions, and follow stereotypical paths for all of their attempts at individuality. Although this sounds critical the story is told in a matter-of-fact non-judgmental way.

A Man Asleep is a rather bleak tale of a young man losing interest in life, probably inspired by Kafka. -

Two intriguing and poignant novellas (Perec's first published work) that you can clearly see had a influence when approaching Life: A Users Manual years later. Forging his trademark iconoclastic literary style that fully emerges in later work, his technique of crowding fictional space with an abundance of almost rococo richly details and decor is also apparent here. So is an air of at first unnoticeable melancholy, that seems to drift around his characters like a ghost.

'Things: A Story of the Sixties' coolly pinpoints the yearnings and malaise of young Jerome and Sylvie, market researchers who analyze their interviewees' needs just as Perec inventories their own. Media slogans and trendy magazines dictate the luxuries they would buy if they had money. To escape the consumerist mythology, they move to Sfax, a drab desert outpost in Tunisia. Even when confronted with luxury, the austerity of North Africa has purged them as much from want as from envy. But although they locate a beautiful villa, their dream eludes them. The narrative slips into future tense: pining for Paris with nostalgia.

'In A Man Asleep' (I prefered this one to the other) Perec asks to what extent a man can detach himself from his fellows and still function. Wandering graduate dropout denies the pressures of time, first by examining each instant as he lies in bed, studying the cracks and flaws in the ceiling of his tiny garret room. Then by drifting through Parisian streets in an imitation of sleep's shadowy oblivion. With Perec, all the little finer details matter, just passing through the day is done in a way that draws vivid images, pondering over life with a thought process that digs deeper into your soul. Despite his characters trapped, weary and decelerating actions, Perec's fertile imagination throughout is fresh and appealing, delivering a worthy read for any Perec fan, and actually a good place to start for anyone thinking of Reading Life: A Users Manual.

An Impressive work. -

For a brief shining moment Things by Georges Perec stood on my real-life to-be-read shelf next to Flings by Justin Taylor, and I had half a mind to go the whole hog and buy Strings by Allison Dickson and Wings by Aprilyne Pike to go with them. Georges would have liked that I think. But I read Flings, then Things and Strings and Wings have faded into the unserious penumbra of whimsy which seems to follow me around most days.

This novel is not really a novel, it’s a rueful self-filleting, a wry meditation , a cool, dry analysis, of Georges’ own generation of early 1960s lower middle-class slackers. I’d bet my next paycheck that it’s 99% autobiography. Jerome and Sylvie, and their friends, all drift from being uncommitted students to casual work for market research agencies, none of them have proper careers. They live in cramped apartments and comb Paris to find affordable objets d’art to stuff them with. They have the taste of the upper middle class but they have no money. Things is page after page of more than a little self-loathing contemptuous analysis of the lives and attitudes of Jerome and Sylvie, with lists of all the stuff they bought, the things. There is no dialogue at all, and no discernible events. Here he is mocking their pretentious political paranoia:

The enemy was unseen. Or rather, the enemy was within them, it had rotted them, infected them, eaten them away. They were the hollow men, the turkey round the stuffing. Tame pets, faithfully reflecting a world which taunted them. They were up to their necks in a cream cake from which they would only ever be able to nibble crumbs.

It must be a French thing, this wry, condescending, academic know-it-all narrator voice – you hear it in Amelie and in Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her and in the novels of Michel Hoellebecq, for instance. Here it is again. It’s tiring. Take a look at this sentence:

In advertising circles – which were generally located by quasi-mystical tradition to the left of centre, but were rather better defined by technocracy, the cult of efficiency, modernity, complexity, by the taste for speculating on future trends and by the more demagogic strain in sociology, as well as by the still very widespread opinion that nine-tenths of the population were fools just able to sing the praises of anything or anybody in unison – in advertising circles, then, it was fashionable to despise all merely topical political issues and to grasp History in nothing smaller than centuries.

Okay, one thing does happen to our tiresome and fraying at the edges couple – they observe their circle of friends dwindling as they each decide to join the salaried middle class properly by getting proper jobs and going to live in the suburbs. To prove they aren’t such braindead materialists as that J & S get jobs as teachers in Tunisia, it’ll be great. Except that one of the jobs doesn’t work out and they end up living in Sfax which is fairly grim, or was in 1962. This is the best part of the book, the disillusion of this brief dream is something we all might have experienced. Sadness and deflation is what this brief novel is all about. You have been warned.

M Perec is clearly a brainy and impressive writer but my God he has that one continual uncontrollable tic running through every other sentence – he thinks it’s his very own cool style – which will set your teeth on edge by page 3. Here is a particularly florid example :

They were in the centre of a vacuum, they had settled into a no man’s land of parallel streets, yellow sands, inlets and dusty palms, a world they did not understand, that they did not seek to understand, because in their past lives they had never equipped themselves to have to adapt, one day, to change, to mould themselves to a different kind of scenery, or climate, or style of living… Jerome could easily seem to have brought his homeland, or rather his quartier, his ghetto, his stamping-ground, with him on the soles of his English shoes… Sfax simply did not have a Mac Mahon, or a Harry’s Bar, or a Balzar, or a Contrescarpe, or a Salle Pleyel, or Berges de la Seine une nuit de juin. In such a vacuum, precisely because of this vacuum, because of the absence of all things, because of such a fundamental vacuity, such a blank zone, a tabula rasa, they felt as if they were being cleansed

So everything has to be Perecised – three synonyms, minimum, or the reader will simply not understand. I felt bamboozled, banjaxed and almost bullied, as if George was prodding his finger, his appendage, his digit right into my sternum, my chestal cavity, my very frontage. -

As David Bellos points out in his introduction these 2 short novels present opposite views. One, of the aspiring young couple who strive and strive, but to what end? The other, of a lonely solitary experience where life appears to have no point.

Don't expect much in the way of plot or character development. But do expect thought provoking literature. -

The author, if still alive, would be as old as my mother. This was his first book and it made him famous. He started writing it in 1962, the protagonists are two young French, a guy and a girl, the type we call now as "young professionals," the setting is in France, circa 1960s of course.

Fast forward half a century later, I'll have my morning coffee at Starbucks, or at the Figaro nearby, and I would be amidst young people, like the characters in this book, and I'll see them tinkering with their latest electronic gadgets, wearing their fashionable clothes, their branded shoes and bags; overhear them talk about their most recent weekend nightouts, who is now going out with whom, their plans for the summer, a trip somewhere, sex beaches, shopping destinations in nearby countries, all the while sipping their cups and puffing thier smokes like movie stars, then when they get exhausted doing the leisurely and remember they need to sleep, will step out, hail a taxi, satisfied that they've escaped the misery of taking much cheaper public transport (bus, jeep) as what they did when they were still studying --all of them out of call centers after their evening shift. And I'd tell myself: these people should read Perec's "Things: A Story of the Sixties" and know that despite these distractions and amusements they happily inflict upon themselves, they belong to another doomed generation. That they are "right in the middle of the most idiotic, the most ordinary predicament in the world" (Perec) from which the majority of them won't be able to escape.

This, then, would be most fun for me: for them to read this book as I watch their faces when they see themselves in there and , by magic, I also get to see their thought processes as they get horrified, in one small step after another, as Perec describes to them their hell. -

An Unclear Exercise in Writing

"A Man Asleep" was published in 1967, and translated in 1990. It is about a young man who gives up his school examinations, his friends, and his purpose in life. He does as little as possible, wants as little as possible, takes as little interest in life as he can. He is "asleep."

The interest here isn't the form of life Perec is trying to imagine, because this is an exercise in writing. (It isn't like Ottessa Moshfegh's "My Year of Rest and Relaxation," superficially for all sorts of reasons, and more profoundly because Perec's subject is writing, not living.) The book is interesting to me mainly because I can't quite tell what the writing exercise is. I can think of five possible precedents or models.

1. Because the character does very little, and spends days on end in his tiny garret, it seems to owe its torpor and pessimism to Beckett, especially early Beckett like "Murphy." But Beckett's willful self-paralysis is presented as a condition of life, of living. Here, it's something the narrator has to train himself for, and it's also an illness, from which he will finally awaken.

The introduction by David Bellos makes it sound as if it's not likely the character will survive his "hell": but at the end, the narrator has several crucial insights. "You were alone and that is all there is to it and you wanted to protect yourself... But your refusal is futile. Your neutrality is meaningless." A character in Beckett would not be likely to "wake up" in that fashion.

2. Because the character wanders all around Paris -- the book is practically an inventory of every park, boulevard, and museum in the city -- it's also reminiscent of Guy Debord. But I don't think that's right either, because Perec is at pains to say that his character is not a flaneur: he doesn't take any interest in what he sees, and in fact he trains himself not to care. The only two people in the book who attract the narrator's attention are a possibly psychotic man in a park, who does nothing but sit and stare, and the narrator's neighbor in the garret, whom he hears through the wall. This is the opposite of Debord's psychogeographies and his derive.

3. A more plausible source, I think, is Duchamp. The narrator cultivates indifference; he trains himself not to judge, not to care. He has an interest in lack of affect. "Indifference has neither beginning nor end... indifference dissolves language and scrambles the signs" (p. 185). There's a telling passage in which he's out in the country, looking at a tree. He says he could spend his whole life looking at the tree, "never exhausting it and never understanding it, because there is nothing for you to understand, just something to look at: when all is said and done, all you can say about the tree is that it is a tree; all the tree can say to you is that it is a tree." (p. 153)

This particular passage isn't Duchampian--it is more late-Romantic natural philosophy--but what comes next shows that for Perec, the tree is the opposite of affect: "This is why, perhaps, you never go walking with a dog, because the dog looks at you, pleads with you, speaks to you... You cannot remain neutral in the company of a dog." (p. 154)

4. I wonder if Nietzsche's sense of the animal is behind some of this. Perec's narrator imagines a life without history, without past or future. Simple, self-evident life, "like a drop of water forming on a drinking tap on a landing, like six socks soaking in a pink plastic bowl, like a fly or a mollusc, like a cow or a snail, like a child or an old man, like a rat." (p. 177)

The character is trying to strip himself of human motivations, which means culture, which means history. "To let yourself be carried along by the crowds, and the streets. To walk the length of the embankments... to waste your time. To have no projects, to feel no impatience. To be without desire, or resentment, or revolt." (p. 161)

5. Or, in the spirit of constrained writing, the perversity of the contraint itself may be what matters. The narrator reads "Le Monde" every day from five to seven o'clock, and sometimes re-reads entire issues. He reads "line by line, systematically. It is an excellent exercise." (p. 168) But "reading Le Monde is simply a way of wasting, or gaining, an hour or two, of measuring once again your indifference." (p. 169) Perec comes close to the supposedly affectless, rule-bound, rote, non-semantic sort of reading that has become associated with conceptual poetry.

I can't decide between these possibilities, and I wonder if the book itself may have been an unresolved experiment for that reason. It isn't like the "Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris," for example, which is more pure in its motivations and execution.

The book is also interesting for its second-person narration. Perec uses the second-person singular informal French "tu," so that the book sounds, in English, like an inner monologue. But it was not intended that way. This edition has an excellent very brief introduction by Bellos, which quotes a line from a review by Roger Kleman: "The teller of the tale could well be the one to whom the tale is told... The second person of 'A Man Asleep' is the grammatical form of absolute loneliness, of utter deprivation." In addition a film version that Perec helped make has a woman's voice narrating the young man's life: all this by way of saying the voice isn't the character's inner monologue, but a speech directed to him. -

Things made me melancholic of the inner life of my early 20s when I stared at shop windows, in love, wanting what I didn't have, imagining the lifestyle posed in magazines and movies and shop fronts. Its a time of desire, longing, wanting, when objects easily influence one's reason. You know why lifestyle marketing works, Perec didn't write sociology and advertising copy, but he got to the heart of this moment in life and our relationship to capitalism and consumption. Even thinking about the book makes me melancholic for that moment in time, before you had things, before you had the money for things, but things conjured so many dreams.

-

120119: these are two short works. it is an error to think of them as ‘novels’. it is mistaken also to think they are nonfiction ‘essays’. in the first case, there is not much interest in shaping the usual furniture of fiction short or long, in the second, there is no careful deployment of rhetoric, assertions, serious arguments, to give the idea that the text means or refers much to any difficult idea...

in fact, the ideas are simple, in ‘things’ the reader is given descriptive form to the idea that maybe the material wealth we accumulate is not connected to any human value except as owner of these ‘things’. in ‘a man asleep’ the reader is given absurd, realistic, fantastic, image of being other than human by having no connection to things of any sort, material or more importantly emotionally, with the idea this is the ‘pure’ way to be human. rather than truly, i suggest, by this severing of desires, simply becoming someone else’s ‘thing’... -

Perec's snappy Story of the Sixties should be subtitled 'The Rise and Fall of the Hipster.' Modern, timeless and deliciously snarky. The only glaring anachronism is the married protagonists' irregular employment as market researchers - replace that with freelance web or graphic design and Perec has perfectly parodied any couple in their late 20s currently vibing on down in Hoxton, Williamsburg or Fitzroy. Highly recommended, this is a satisifying yet quick read UNLESS you over-indulge in the litany of ideal home furnishings that Perec satirises in the opening chapters. His descriptive prowess provoked a two hour SchadenGoogle as I abandoned the book to conduct an impromptu search for the perfect bookcase to populate my perfect library currently being equity funded via the currency of hopes, dreams and delusions. I AM the person that Perec is parodying. Excellent. Four stars, that man.

Sadly, the novella in the bunk below, 'A Man Asleep', is all rather hopeless - a shuffling two star character sketch that attempts to describe a student teetering on the precipice of lethargy. Oblomov it isn't. The narrator's voice tees off in a very self-assured tone, conjuring up the odd shapes that flit across our corneas as we descend into (or ascend from) a semi-somnolent state. It's all very precise, a bit tricksy and totally misses the mark. Perec trots on, blithely assuming he's hammered home a winning streak of images and allusions whereas he's executed the literary equivalent of nailing a jelly to the wall. Flabby, incoherent and really rather dull. -

It's Perec isn't it? Never let me down yet. These are his first 2 novels, so his experimentalism hadn't yet fully developed yet. But these are both fascinating in their own way and brilliantly written.

Video review to follow, -

When I was in my early twenties, I lived by myself in a huge, somewhat derelict building. It had two floors, three bedrooms, of which I left two empty. It was in a city in which I knew few people, and liked even fewer. I studied there, which amounted to about six hours of classes a week. I didn't do much else. I hardly read books, hardly went out to meet old friends. Instead, I walked. Aimlessly, fruitlessly; pointless walks to dismal places. Dismal walks to pointless places. At night, I couldn't sleep. The silence smothered me. Or, as Perec says: I stopped speaking and only silence replied. It was too much. I had to wait, basically sitting around in one empty room or another, for the sun to rise, for the birds to sing, for my neighbours to rise and go to work. I would sleep through the day, get up, walk around, sit through the night. It seemed like entire lifespans passed me by then. What it boiled down to, though, was merely a very long summer.

Yet, as in Perec's A Man Asleep, the indifference and emptiness of that summer did not arise out of nothing, did not come as a surprise. It was surrounded by more emptiness, less or more dense, more or less dense. I don't remember the day, or the week, or the month, but it must have been that summer, and there must have been a day indeed, when I too discovered, without surprise, that without mincing words, that I did not know how to live, and that I would never know. It might have been that summer, or a summer before, or after, it doesn't matter, that I watched the film version of A Man Asleep, watched - or glimpsed - it endlessly, bits and pieces, YouTubed segments, the hypnotic drone of the narrator's voice speeding up, lulling me from one nothingness into another. When those words, those italicised words above, came up, what I liked about them was the without surprise, the studied insouciance of that interjection, the lack of melodrama in it. There is a man sitting in a room, sitting on a bed, and he realises something. But this is no eureka moment. It is more like confirming what you knew all along, like the fifth replication of the outcome of some experiment. This man, sitting in a room, sitting on a bed, might just nod slightly, altogether imperceptibly, to himself.

What is so incredible about A Man Asleep is the pace, the endless enumeration of the same things, of walks, cinemas, bars, of turning left, turning right, turning left again, of sleeping and not sleeping. Short as the story is, it nevertheless endlessly doubles back upon its own tracks. Which is to say: its style mirrors its subject. The British band The Clientele does a similar thing in their music: their every song encapsulates the same thing, a haziness, a glimpse, a world where rain never pours but always drizzles, yet where skies never quite clear up either; a world, too, eternally observed from behind a window, at a remove, not quite there, a world seen through distorting reflections. As it happens, The Clientele has one song which perfectly accompanies A Man Asleep. It is called "Losing Haringey", and features a narrator who drifts aimlessly through nighttime suburban London ("In those days, there was a kind of fever that pushed me out of the front door...", it begins). There is too, as in Perec, a finely-calibrated description of surroundings, an oddly imbalanced focus on the things that we usually gloss out:I found myself wandering aimlessly to the west, past the terrace of chip and kebab shops and laundrettes near the tube station. I crossed the street, and headed into virgin territory - I had never been this way before. Gravel-dashed houses alternated with square 60s offices, and the wide pavements undulated with cracks and litter. I walked and walked, because there was nothing else for me to do, and by degrees the light began to fade.

This endless return to one question, one probe, reminds me a little of the Serbian novelist Milorad Pavic, who claimed that his novels were like sculptures that you could walk around. His most famous work, Dictionary of the Khazars, is supposed to be read like a hypertext, jumping back and forth between entries, but with the catch that all entries are essentially telling the same story; it does not have the breadth and scope of a real dictionary. It is a kind of trick of the light, the unknowable, true meaning fractured into a kaleidoscopic panorama.

* * *

But all of that was then, which suggests that now must be now, and somehow different from then. As I read these two novellas, I couldn't help but notice that I drifted against Perec's chronology, from his second novella into his first. Somewhere along the line I got a job, a decent little job, a temporary little job that for all intents and purposes feels pretty solid, feels pretty ongoing, feels pretty endless. I sleep relatively sound, live relatively regular hours. I vacate and vacillate behind the telly sometimes, like everyone else. Finally like everyone else. I might still have vague plans to the future, but they are forever indiscriminate; they exist in a meaningless void, side-by-side, I could take or leave them, probably. Like the couple in Things, I too could up and leave, could go to a Sfax of my own, and if I did I would go for exactly the same inane reasons as our protagonists do: because it would bear the semblance of change, because I would like to believe that a different city means a different life. Such vague plans not only provide me with little hope, but they also prevent me from putting down roots. I am somehow still in Perec's other book too, in that "blessed parenthesis" he mentions somewhere, the bubble that time forgot. Neither coming from somewhere nor going anywhere:For Christ’s sake, our young lad thinks, am I going to have to spend my days behind these glass walls instead of going for walks in flowery meadows? Am I going to catch myself hoping the night before each promotion exercise? Am I going to calculate, connive, champ my bit, me, who used to dream of poetry, of night trains, of warm sandy beaches? And, taking it mistakenly to be a consolation, he falls into the trap of hire-purchase. Then he is caught, well and truly caught. All he can do is to gird up his patience. Alas, when he gets to the end of his troubles, our young man is no longer quite so young, and, to cap his misfortunes, it can even seem to him that his life is behind him, that it consisted only of his striving and not of what he strove for, and even if he is too cautious, too sensible - his slow climb has given him plenty of experience - to dare to say such things to himself, it will none the less be true that he will be forty, and straightening out his home and his weekend place and his children's education will have filled more than adequately the few hours he will have been able to spare from his work...

(...and you may find yourself in a beautiful house, with a beautiful wife, and you may ask yourself... how did I get here?...)

Hire-purchase of course being the perfect metaphor, a trap indeed, but also a way of life, a kind of purgatory on earth, a hoverboard for the soul. Hire-purchase is a way of writing off the currency of your lifeblood without any returns, without even a receipt, and an efficient vehicle in which to speed semi-consciously to and into mid-life. We'll wake you up when we're there, someone might say.

In "Losing Haringey", the narrator walks on until he sets himself down on some park bench, only to suddenly find that he has wandered into an old photograph. The two realities somehow merge:I was still sitting on the bench, but the colours and the planes of the road and horizon had become the photo. If I looked hard, I could see the lines of the window ledge in the original photograph were now composed by a tree branch and the silhouetted edge of a grass verge.

Of course the inevitable happens, and the narrator experiences a kind of Proustian collapse:Strongest of all was the feeling of 1982-ness: dizzy, illogical, as if none of the intervening disasters and wrong turns had happened yet. I felt guilty, and inconsolably sad. I felt the instinctive tug back - to school, the memory of shopping malls, cooking, driving in my mother’s car. All gone, gone forever.

Nostalgia, the past - they are curious things. We speak of intervening disasters, wrong turns, we think there are trajectories between where we were then and where we are now. But if pressed, they become hard to pinpoint. I don't quite know how I spiritually drifted from A Man Asleep to Things, and/or where exactly on the Perec-spectrum I currently am. The book as I have it, the two novellas combined, feels like the Before and After of something important, some great event that nonetheless never transpired. There has been no intervening disaster. The arrow of life has moved forward, yes, but I could not catch it in motion in any one singular frame. And yet here I am.

Almost near the end of A Man Asleep, Perec describes one of the walks as feeling "like a messenger delivering a letter with no address." This is pretty apposite. What keeps me going is the idea that there might be something (of whatever kind) out there, that the world is too big to rule out any surprises, positive or negative. But to be honest, unless you are Jonathan Safran Foer, the odds of delivering a letter with no address in a big, big world, are pretty slim. -

Things: A Story of the Sixties gets a very strong 4/5. Review forthcoming--first I've got to get right into A Man Asleep!

A Man Asleep gets a very "eh" 2/5. Further, I'm particularly mad at it for two additional reasons: 1) it isn't a separate book (I mean I couldn't find a separate publication of these two anywhere!), so these two books only count as one book on my reading challenge! (Yeah, I actually think about stuff like that, and yeah it burns my biscuits.) 2) I was so jazzed up after reading Things: A Story of the Sixties that I probably could have written a pretty good review: you read A Man Asleep and you become less enthused. You suddenly lose passion for what you once enjoyed. You drink some nescafe. You keep reading the book and thinking that it reminds you a bit of Beckett and you don't really enjoy most of his stuff. You find it tolerable, but tedious and repetitive. You find it repetitive and tedious. You do kind of like that it's in the 2nd person, though. You thought that would be annoying, but it has its charm. Will you ever return to write a proper review of the book you actually liked? Only time will tell; "time would have had to stand still, but no-one has the strength to fight against time" (219).

Now I can't wait for Perec's "e" books to arrive in the mail; otherwise, I'll have to start Life: A User's Manual, and that's looong(ish). Byeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee. -

Two early novellas in one book. "Things," the first novella, includes maybe some of the best autobiographical-seeming expository stretches (no dialogue, no traditional scenes) about life from age 21 to 30 (albeit here in the '60s in Paris and Tunisia) I've read. Perec's obsessive detail/description is like Nabokov but not as precious/obtuse, plus he's consistently insightful, often unusual, and so generous in terms of perception and wisdom. Someone should reissue this novella solo.

"A Man Asleep" I'll admit to not finishing -- a second-person (apparently Lorrie Moore didn't invent the POV) studenty slacker Handke/Beckett-type exercise in describing nothingness, in not doing, in indifference/detachment. Excellent and worthwhile in terms of descriptions of a young man's life (mostly) in Paris in the early '60s, but even an intentional project by a writer as good as Perec to describe cracks in the ceiling and what you see when you close your eyes or what it's like to read the newspaper didn't really seem to me to serve as too much more than an excellent soporific. I'll keep it by my bed and use it as such when necessary. Admirable and all but I need to move on to something else for now. -

Me pareció demasiado frío. Supongo que es una especie de caricatura, o algo, porque te cuenta sobre personas lejanas, de quienes en todo momento habla en plural, haciendo cosas con las que evidentemente no está de acuerdo. Tiene frases lindas y trabajadas como suele tener, pero de emoción queda medio nulo.

-

My review of Things

here

My review of A Man Asleep

here -

پنجتا که هیچ، تو بگو هزار ستاره.

نوولای اول، «چیزها»، با هر جمله از نو شگفتزدهم میکرد. شیفتهی این بودم که چیزها شخصیت اصلی متن ن و نه ژروم و سیلوی؛ اصلن ژروم و سیلوی تا انتهای نوولا حتا حرف هم نمیزنن، چه برسه به این که بخوان محور متن باشن. نگاه دقیق و موشکافانهی ژرژ پرک و وصفهای سهل ممتنعِ مختصرش برای من بسیار دوستداشتنی و یادگرفتنی بود و نثرش بیاندازه زیبا.

نوولای دوم به نظرم شبیه به نسخهی تعدیلشده و انتزاعیتر و کلیتری از «حباب شیشه»ی سیلویا پلات اومد؛ با همون بخش اول، که بهخوابرفتن رو توصیف میکنه، خودش رو در قلبم جا کرد و با بخشهای دیگهش و با بعضی عبارتهای درخشان جاش رو تثبیت.

بار دیگر، امان از نثرهای زیبا و انسانهای نکتهبین. کتاب بعدیای که شروع میکنم «زندگی: دفترچهی راهنمای کاربر» خواهدبود و بنا به شنیدههام قراره بشه کتاب بالینیم و کاش ناامیدم نکنه، که بعید میدونم بکنه. -

Twee sterke verhalen over consumerisme en zingeving in de Franse jaren 60. De boeken hebben een unieke schrijfstijl zonder enige dialoog, wat het centrale centrale thema van vervreemding in de moderne samenleving erg goed ondersteunt. Het deed me in veel aspecten denken aan

De avonden en is zeker aan te raden. -

2 early pre-OuLiPo novels of Perec. Given that Perec is in my top 10 favorite writers, I read everything that I come across by him & he can, basically, 'do no wrong'. As is usually the case, I like creative people who continue to be creative: ie: who manage to make new work that's significantly different from their older work. Perec exemplifies this. Each thing I've read by him has been significantly different from each other, each has been strong.

I'd call both novels vaguely (or, perhaps, not so vaguely) Existentialist. Wch is weird for me b/c I don't think I've ever called the writings of anyone other than the obvious Camus & Sartre that. They're not so vaguely sad & make me think of writing in general as a form of 'insanity'. I mean, what type of person chooses to spend their time in what's usually a highly isolated & isolating activity - probably in the hopes that other (often also isolated) people, the readers, will experience the product? THEN, who chooses to have that product be about, 1st, in "Things", a subtle (or not so subtle?) sense of perpetual dissatisfaction typically critiqued as "consumerism" but, perhaps, more indicative of an even broader human condition: a striving for the 'impossible' (or unlikely); & 2nd, in "A Man Asleep", about a person whose depression practically reduces them to a zombie? (Did you forget that that long-winded sentence was working toward being a question?)

According to David Bellos' introduction, Perec, himself, went thru a similar period to that of the main character (essentially the 'only' character) in "A Man Asleep". I'd've pretty much taken that for granted even if Bellos hadn't so informed me. The character, who mostly drops out of social society, reminds me of a guy I know who's reputed to've been a law student at a local university. Now he's a street person who claims he doesn't know what happened to himself - except that he developed a problem of feeling "paralyzed" & incapable of doing things. He says he tried to hang in there but cdn't. Now he's widely known as being the filthiest street person w/ the most tattered clothes. Perec's character fares much better. For one thing he has money that he budgets carefully, he has a place to live, he can afford to eat & go to the movies, he stays clean. But, otherwise, he's somewhat mind-numbing to read about.

&, of course, there's Perec's writing itself. His descriptions are marvelous & sensitive - no doubt in large part, here, thanks to David Bellos' & Andrew Leaks' equally marvelous & sensitive translations. -

Wow. Things: A Story of the Sixties is so incredibly topical today, it feels oddly modern, even though so many of the brands and lifestyle nods it name-checks aren't on anybody's radar today. There are sloggy bits (the first few pages are like a description from a French 1960s "House Beautiful" or something), but once you get into the somewhat flat third-person writing style (which doesn't allow for much interiority -- perhaps fittingly!), it's a fabulous little novella. And it's a scathing critique of the way modern western life is based around consumption ("But money -- and this point cannot but be an obvious one -- creates new needs.") Every other page seems quotable: "They lived in a strange and shimmering world, the bedazzling universe of a market culture, in prisons of plenty, in the bewitching traps of comfort and happiness." Things is light on plot, with the most momentous shift occurring when Jerome and Sylvie (the never-ending "they" of the narrative) move to Sfax, Tunisia. Sfax is an interesting antidote to Paris, but one with its own massive problems for the young expat modern couple, and Georges Perec seems to suggest in the end that you can run, and run, and still never find a happy medium between the two worlds.

The other novella published in tandem with Things is A Man Asleep, which isn't nearly on the same level of brilliance as the former. Or maybe its brilliance is precisely the fact that you come to hate it -- absolutely hate it -- as you read it, for it meticulously and relentlessly forces the reader into the world of the horribly, horribly depressed student who doesn't wake up for his exams one day and then spirals into a meaningless and hopeless existence. Of course, it's fairly obvious why the two novellas are paired -- seeking meaning in materiality, and then renouncing meaning altogether makes for a nice contrast, but I found A Man Asleep to be a punishing sort of read, and desperately wanted the nameless student to get himself to a psychiatrist, stat. -

This combines two novels from Georges Perec. I admit they weren't hugely to my taste, but they were well written and an interesting study in contrasts.

Things is about a Parisian couple in their 20's. They have a deep hunger to live the good life, and try any and everything to get there. The story is largely about materialism, and people not living the lives they think they deserve.

A Man Asleep is the story of a young student who veers in completely the opposite direction, and desires nothing, even working to rid himself of desire in general. It's a bleak piece. The main character/narrator never even gets a name.

I'm not a big "literary" reader a lot of the time, but I try and branch out occasionally. This was such an attempt. I appreciate the talent behind the writing, it just didn't really click for me. -

Θα επανέλθω αναλυτικότερα καθώς διαβάζω για τρίτη φορά και τις δύο ιστορίες του βιβλίου.

Το "A man asleep" αν το είχα διαβάσει 2-3 πριν θα ήταν μέσα στα 4-5 αγαπημένα μου βιβλία. Το "Things" μου άρεσε λιγότερο απ' το "A man asleep", αλλά δεν μπορώ να σταματήσω να το σκέφτομαι.

Σίγουρα καταλαμβάνει πολύ χώρ�� μέσα μου. Βάλε και το ότι διάβασα σχετικά πρόσφατα το "Ούτις" του Σαμσών Ρακά, θα κάνω καιρό να πιάσω άλλο βιβλίο.

Μέχρι μέσα Μαρτίου, μόνο artbooks των ταινιών του Miyazaki!

ΥΓ: Ευχαριστώ την πιθανότατα μεγαλύτερη φαν του Περέκ παγκοσμίως που μου το έδωσε. -

I came across Georges Perec in a round about manner. A while ago I was reading short stories of one of my favourite writers Italo Calvino. I kept thinking that some of the stories were peculiar in the way in which they were constructed -- even by Calvino standards! I already knew about Calvino’s deep interests in mathematics, astronomy, and computers. While reading a short story called The Burning of the Abominable House I got to know Calvino’s association with a certain movement called OuLiPo. That was an "aha!" moment.

(As as aside, this short story by Calvino was published in the Italian version of Playboy (yes!) in 1973. It has more complexity and intrigue than most classic film noir thrillers such as Double Indemnity. It's more futuristic than The Minority Report, Black Mirror, and everything else put together.

You can read it here.)

The French expansion of OuLiPo translates to “workshop of potential literature”. It was an informal gathering of European (mostly French) writers and mathematicians. OuLiPo writers sought to create works of literature using constrained writing, wordplay, and mathematical patterns. It was while reading about OuLiPo works that I happened upon Georges Perec who was one of its prominent members. (One of his novels is a lipogram — he’s apparently written the entire novel without using the French letter e.)

I have wanted to read his books since then. So, I recently started with this book that has two of his earliest works — before his OuLiPo days — both novellas: Things: A story of the Sixties, and A Man Asleep. Both of these are what can be called as “observational novels”. There is hardly a plot, no events of significance, not much character development — all effective tools of a conventional novel. Like many other European novels, it takes an essayistic approach and presenting a worldview rather than advancing a storyline.

In Things, Perec observes a young couple as they live their life in Paris constantly dreaming of a higher living, but their entire idea of a better life is revolves around, well, things — they dream of riches, of acquiring the best artefacts in the world. They want an easy route to the riches though — like receiving a letter out of the blue with the news that a rich old uncle has died and passed on his entire fortune to them. They abhor the rigamarole of regular work.

Things describes the tragicomic plight of this couple in precise details as they wade through their life without purpose. Towards the end of the novel, they seem to realize that there is no great escape, there’s no miracle waiting to happen; they seem resigned to “settling” into a regular life.

A Man Asleep is almost a counterpoint to Things. In Things, Jerome and Sylvie, the young couple, are all about fascination, they want to have everything. Here on the other hand Perec follows the life of an unnamed 25 year old student who has given up, who wants to personify indifference, who wants to observe life as it goes by without attaching any value or emotion to the goings on.

A Man Asleep is one of those rare novellas with a second person narrative. In that sense, it’s a doubly observational novel — you are observing the novelist’s observations. Or maybe triply so: you are observing the novelist’s observations about the protagonist’s observations.

It’s partly autobiographical. Apparently, Perec did go through a period of severe depression in his twenties. In A Man Asleep he draws from his personal experience of going through a period of depression and indifference, and elevates that to an art form. The level of visual detailing in the novel is compelling, it’s often cinematic (in fact, I learned that both these novels were made into films!).

In either of his novels Perec doesn’t reach any conclusions. It is left to you the reader — the onus of making the lives of his protagonists better or worse is more yours than his. In A Man Asleep, there are hints of a reawakening, a coming back to reality of sorts at the end of the novel. However, the feeling of not reaching a closure is more acute than that in Things. -

This was my first return to Perec in the better part of a year, and I was not disappointed in the slightest. This 2-pack offers two novels which, while totally equipped for life alone, accomplish much more in this dual package. Les Choses (Things) is the star of the show here, with creative subjunctive language that not only manages to tell the story of an entire generation through a simple tense change, but also tells a “story of the 60s” which speaks to life in 2023 with an accuracy not dulled by time in the slightest.

A Man Asleep tells a tale which belongs with the best of obsessive paranoid writing: The Burrow, Ancient History, Notes from Underground, ad infinitum. The use of 2nd person pronouns forces the reader to think about the plight of the narrator in a unique way, and while the prose or overall message fails to deliver the universal gut-punch of truth that Things manages, the abundance of nuggets of truth throughout make the read fully worthwhile. -

You think that the idea of retreating from the world out of resentment of the numerous obligations that normal life hoists upon you, and having this turn into an almost Buddhist and contradictory desire for non-desiring is a great theme. You also believe that the primary gimmick of this book - the second-person perspective - plays into this by providing a detached 'version' of first-person writing. You find, however, that the gimmick and the writing around the theme had a tendency to be repetitive. This may also be part of theme, but you don't find that this makes for a better experience. Nonetheless, you recommend this to friends, with the caveat that it could have gone further.

-

my partner got me this book for my birthday bc the second story is about a man who becomes so depressed he almost ceases to exist – he (correctly) assumed i would find it relatable. i’m pleased to announce that i related a lot less than i once would have had, which is excellent news.

this book was written before oulipo and the use of language is therefore less playful than i assume it is in perec’s later works. however!! i still thought the writing was great and interesting and really set this work apart from others that i have read this year. -

Les Choses is very noticeably a debut novel. Which isn't to say it's bad. As a sarcastic nod to Sartre (as if the title didn't give it away) it's not crap, as a satire of Mad Men-style materialism (it's subtitled a history of the 1960s, published in 1963) it's lost none of whatever sting it had - living in Stockholm's hipster neighbourhood in 2013, I know these people personally. (Hell, I probably am them.) And even if the satire is a bit too obvious, Perec delves beneath it - turning the never-ending litany of objects and what they symbolise into an almost mystical experience; it's not a sibling of Herzog's Fata Morgana, but definitely a distant cousin.

That said, it's not a nice novel by any stretch. Young Perec is ruth- and merciless in the way he eviscerates his characters... actually that's not correct; in order to eviscerate them he'd first have to flesh them out, and Jérome and Sylvie only exist as would-be consumers, defined only by what they want and cannot have (which we're told outright by the none-too-subtle narrator). It's a novel to admire, but unlike much of his later work, it sneers where it might have winked. -

The first two books by Perec display some of his influences and the foundation of some of his stylistic tendencies. The meticulous cataloging of objects and decor, room by room, in various dwellings presages the later Life: A User's Manual and evokes Alain Robbe-Grillet, plus no Frenchman can write about the hypnagogic state of awareness without someone thinking of Proust.

"Things" draws on Perec's own experience as a young man of working in the nascent field of market research (as well as some time in the provincial Tunisian city of Sfax). The rise of a wealthy consumer society and the various industries to support it, exemplified by a couple in their 20s striving to attain an idealized life-style while hoping to somehow escape what they consider the bourgeois trap, is a story mirrored in many subsequent cities and decades.

I think these two predate Perec's involvement with the literary games of the Oulipists, but there are some structural devices of note; entire chapters written in the conditional or future tense, or in the case of "A Man Asleep", the entire novella written in second person singular. -

The first novel in this book, Things: A Story of the Sixties, outlines a 20-something couple in 1960s Paris. They are incredibly materialistic, and the only interesting thing that they really do in the whole book is decide to temporarily move to Tunisia. Which of course they hate. I wish something else of note had happened, because these two characters were pretty crazy (in an interesting way).

I did not finish the second novel, A Man Asleep. The first half describes a college (or maybe grad school?) student's descent into depression. But there is apparently no reason for how the depression comes about, and chemical assistance is never discussed (not that it's always effective, but it might have made this guy more...I don't know, interesting? I know I've used that word too much already in this review, but I'm at a loss--I was really uninterested in this book).

I know there is a lot more to these philosophical novels, and I'm sure that I missed a lot. But for now I'm going to lay off of French novels.