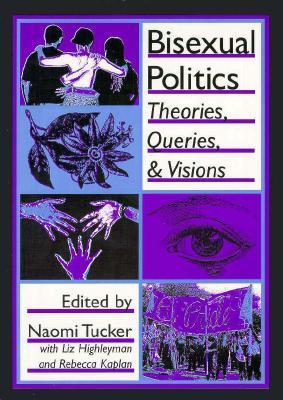

| Title | : | Bisexual Politics: Theories, Queries, and Visions |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1560238690 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781560238690 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 386 |

| Publication | : | First published September 13, 1995 |

Bisexual Politics: Theories, Queries, and Visions Reviews

-

collection of essays, circa 1995. there are some really stellar ones in here, also some mediocre ones and a few that are just outright bad. one of the first books published that really began to articulate bisexual politics. highly recommended for anyone who notices or is annoyed by the omission/marginalization of bisexuals and other queers in gay and lesbian theory and politics and in the world in general. big focus on how/why bisexual politics emerged from bisexual women within the lesbian/feminist movement of the 60s70s. good stuff.

-

like the other bi books i’ve read, this is repetitive and binary. but it’s very slightly less so (lots of talk about blurring gender and breaking down binaries, but binary genders are pretty much the only ones acknowledged.) and it isn’t a bunch of personal (sexual) histories, so i enjoyed it more.

(this is also another example of a old-ish bi book that sometimes uses “regardless of gender” and “not determined by gender” language but still in the context of men and women.)

content/trigger warnings; mentions and discussions of biphobia, mspecphobia, queerphobia, homophobia, lesbophobia, transphobia, nonbinaryphobia, racism, sexism, misogyny, mentions of rape/sexual abuse, interphobia, medical abuse, lesbian separatism, terf/radfem ideology,

as always, here are some quotes:

We do not all share the same goals. We do not even share the same definitions of bisexuality!

The early 1970s saw the first public claiming of the bisexual label to promote acceptance and visibility of bisexuals.

We each craft our own self-identity and choose words to describe ourselves according to our cultural and personal histories. The bisexual community should be a safe haven that honors the fluidity of sexual identity. A place where people can choose the labels that fit them best—or choose no labels at all—without fear of losing the community they call home.

Tensions between lesbian and bisexual women are understood as much more problematic than tensions between gay and bisexual men. To a large extent, these differences reflect the way lesbianism was politicized within feminism, such that a culture arose with clearly delineated norms of acceptability, norms which bisexual women—by definition—broke. Gay male culture did not become nationally politicized until the advent of AIDS, and life before AIDS in the baths and discos, at the bar or the opera, did not exclude bisexual men in the same way that lesbian space came to exclude bisexual women.

By 1978, the year that Chicago’s Bi-Ways was founded, the definition of lesbianism had shifted somewhat. The cultural norms had solidified; proper dykes would not be caught dead in a dress, a Burger King, an MBA program—or in bed with a man. At the end of the 1970s, rather being a woman-loving woman, a lesbian was a woman who did not sleep with men. Of course, some lesbians did sleep with men, and those who did kept this fact about themselves hidden.

Lesbians critical of bisexual demands have framed the problem as the bisexual desire to invade or infiltrate lesbian space, but hopefully it’s now clear that for many bisexual women, there was no question of invasion; we had been a genuine part of lesbian feminism, and our call for explicit inclusion as bisexuals was meant to rectify what we perceived as an injustice of silencing.

Bisexuals also turned to queerdom, finding affinity in the norms off androgyny, genderfuck, and “in your face” politics among a decidedly mixed-gender group of people.

Some bisexuals have never consciously identified as anything other than bisexual, having either identified as bisexual early in life or having previously had an unspecified or “none of the above” or “heterosexual by default” identity.

In some circles, bisexuals (along with drag queens, leatherfolk, and others) are seen as a threat to assimilation because they seem to reinforce stereotypes that non-heterosexuals are amoral, confrontational, and promiscuous.

Previously, a woman could be a lesbian if she loved and was committed to women, but by this period lesbianism seemed to become more defined in terms of not loving or having sexual relationships with men.

Some bisexuals have hopped on the “born that way” bandwagon, but in general bis tend to be more amenable to the idea that there is flexibility and some degree of choice in the realm of sexuality.

Some proponents of sexual and gender liberation have coined terms such as “pansexual” and “omnisexual” to describe their aspirations, but no term for this movement has so far achieved common usage.

For me, it all comes down to choice. Ultimately, “after the revolution” if you will, what we should all have is choice. Among other things, the choice to fuck whomever, love whomever and however. And call it whatever you want (or call it nothing at all), even if someone else wants to call it something else.

Sexuality and sexual identity are fluid and change over time. People need to be able to call themselves whatever they need to in order to let themselves do what they need to.

The use of “queer” can be empowering. It refers to a radical tendency in our community to seek liberation and self-determination, not assimilation into the white, male-dominated, heterosexual culture.

Contrary to what the monosexist paradigm would have us believe, we do live in a world of fluid constructions of desires, genders, and sexualities. There are many who choose to have sex with all genders in varying relational configurations and who do not necessarily identify with any labels.

Identity definitions blur and change.

Many people who are sexual with both men and women, yet not bi-identified, do not seem to be plagued with internalized biphobia or an unsupportive environment. Some prefer to call themselves “queer” rather than “bisexual”; others, when asked, may say something like, “I don’t like labels,” or “I’m just sexual.”

It’s important to remember, in the midst of our myth bashing, that while the myths and stereotypes don’t describe all or even most bisexuals, there are those of us who are promiscuous, are nonmonogamous, do like to have both male and female lovers at once, do like three-ways and four-ways and six-ways and fifty-seven-ways more than any other way, are more interested in sex than in politics...and that this is okay.

A number of lesbian women and gay men I met did S/M together, but did not consider themselves bisexual. They were simply doing what has come to be called “pansexual play.”

I have the right to claim my lesbianism and my bisexuality even it confuses you. I am a lesbian. I am bisexual. I am a bisexual lesbian. Deal with it. (1991)

The different ways people identify as a bisexual: gay-identified, queer-identified, lesbian-identified, or heterosexual-identified. Some people are bisexual in an affectional manner only; some are bisexual both affectionally and sexually; and some are bisexual only sexually. Since there are so many ways to express our bisexuality, the first step toward alliance-building is to work internally to accept all members of our own community. Acceptance of the diversity of bisexual labels within our community will allow us to pursue alliance-building with decisive strength in the heterosexual community and what many of us consider our own lesbian/gay community.

I believe in the right to identify as we see fit.

Respect other people’s identities. Don’t say that “everyone’s really bisexual.” Don’t say that bisexual people are somehow more evolved. Don’t raise your own self-image at the expense of other people. Examples of bad ideas taken from real life: a t-shirt that says “Monosexuals bore me”; a button that says “Gay is good but bi is best.” Please.

It amazes me that we’re still excluded after all the years of organizing. Bisexuals have fought alongside lesbians and gays for queer liberation since Stonewall and before. [...] it still happens. From people who know how painful it is to be ignored, how degrading assumptions can be, from the people who coined the phrase “Silence Equals Death,” it still comes, or rather, it still doesn’t, those two simple, beautiful words: and bisexual.

Saying “queer” is the best way of being all-inclusive.

Unlike the mainstream segment of the gay and lesbian movement, bisexuals have not restricted the project of deconstructing identity-based categories to academicians. Rather, bisexual both within and outside the organized bi movement have made this project an integral part of how we make sense of the world and live our lives as bisexual, pansexual, omnisexual, multisexual, “just sexual,” androgynous, genderfucked, bi-gendered, non-gendered, gender-indifferent, or “don’t label me” human beings seeking to create communities with those with whom we find common cause, even (or maybe especially!) if our labels don’t happen to coincide.

All of the prominent models of sexual orientation that I have seen also share two additional problems: they do not account for traits other than sex/gender that may also be important in determining people’s attractions, and they do not account for which specific sexual acts people prefer.

When I write the word bisexual, I intend to refer to people who (a) call themselves bisexual; or (b) experience their desires as not falling along sex categories; or (c) are sexually attracted to people of more than one sex (be that male, female, or other flavors for which we don’t yet have good word).

Radical bisexuality must embrace a future with gender plurality as well as orientational fluidity. Labels such as “pansexual” and “polymorphously perverse” may reflect this view.

Currently, voices within our movement are breaking down borders once again. We are no longer simply bisexuals. We are also autonosexuals, omnisexuals, pansexuals, polysexuals, ambisexuals, trisexuals (because we’ll try anything!). While the real meaning of these terms is presently implied, exotic, vague, and opaque, their very existence is promising. What all these new terms and sexual identities suggest is an expanding consciousness vis-à-vis sexuality. They are saying: “The limitations of language, the existing terms, do not encompass the enormity and explosiveness of my sexuality.” -

This book is hard to rate to say the least. There's some essays I'd give a 0 (or less) and recommend avoiding (or at least reading very critically) because of the overt transphobia. There's some essays that are 5 stars and that are written by trans people. I went for two stars mostly because of the overt transphobia in some of the essays.

I'd recommend this book specifically for people looking for a time capsule of 1990s queer, specifically bisexual (and mostly cisgender and white, with some exceptions) politics and points of view. I'd recommend it to anyone trying to look into the history of bisexuality or queer politics and who's curious how stances have evolved.

What surprised me is how many of the arguments within these pages (identity politics and their validity; bisexuals' place in the larger community and the relationship to the lesbian, gay, and transgender communities; bisexuality as "trendy"; bi erasure; respectability politics) are still ongoing today. -

This got entirely out of hand, but I think it speaks to how thought-provoking a read this was. Almost every time I flipped to the next essay, I would think, "woah, this is really good." (Sometimes I would think, "hm....") Highlighter all over. Some of it is the basic "acknowledge us, we are a valid identity" (and sometimes says it well), but a lot of it gets more into community-building, the intersections of oppression, and the specific systems in place that lead to biphobia and homophobia. Even thirty years later, this book raises some good questions and gets the juices flowing for thesis topics.

If anything, this book made clear the fact that we keep inventing the same old shit every decade. Nothing new under the sun. Queer discourse is like crabs.

Also, the longer I think about it, the homo/hetero/bi trichotomy is not helpful or sufficient for encapsulating most of human behavior. >50% of people purport to fall somewhere above a Kinsey 0. A large chunk of people who frequently have literal gay sex identify as straight. A lot of people who identify as gay/lesbian have 'straight' sex in secret--even after coming out as gay/lesbian and finding the community--or seek out S/M venues where they're 'allowed' to interact with other gay people of a different gender. Many, many people pursue gay sex in settings like prison, same-gender schools, and the military, when they don't have 'access' to 'straight' sex. For most of pre-Christian human history, it was normal and expected for people--men, at least--to take sexual partners regardless of gender. Who knows what that looked like for humanity before recorded history. Homosexuality and bisexuality is demonstrated in countless other species.

In a better, different world, we would not sort ourselves based on what genders we're attracted to, and in this one...it's just a false schema. It's not even helpful beyond lubricating the machine of oppression and/or avoiding being ground by its gears. Reclaiming a 'homo' identity is a survival mechanism, but comes at the cost of perpetuating the system that causes you to need a survival mechanism. Most humans don't work that way, and we need people to know that we don't work that way.

It is a violence to tell lesbians, "you just haven't found the right one!" when some lesbians will have spent their entire lives having never been attracted to a single man and suffering for it; it is a violence to call lesbianism "a lifestyle choice" as in, You stop that right now.

But we also cannot ignore the fact that many self-identified lesbians have been or are still attracted to men. The instinct might be to kick them out, go join the nasty bisexuals, nothing less than Kinsey 6 can stay, but a 'pure' Kinsey 6 soul is rare. And what of the lesbians who have had sex with men, been married to men? What about lesbians whose ex-partner transitioned? Whose current partner transitioned? Who transitioned themselves? Who don't identify as binary she/her women? Do we send them out too? Does there need to be a ~safe space~ for 'gold star' lesbians, away from people who didn't have it figured out from birth, who didn't 'stick to their convictions'? Why? It's nice to meet a kindred spirit, I get that, but why are we socially and politically othering women who are already othered--women who could be our allies, friends, and lovers? And why is it always, always upper-middle class white women who are so concerned with excluding the WLW who don't meet their very strict standards?

Why are we letting the presence or absence of men define our sexuality, rather than our relationships with women? Why would any woman's sexuality 'center' men, let alone a motherfucking lesbian identity? In making our obsession excluding men, we are thinking about men all the fucking time; you can't play whack-a-mole without moles. Why are we whacking moles? Why aren't we smelling candles at Target together and kissing with tongue? In defining yourself by your opposition to the majority, you continue to define yourself by the majority.

Do we let women who are happily married to men identify as lesbian...maybe with the caveat that their primary attraction is to women, if all of their friends are lesbians, if they've dated only women before, if they cut their nails short, etc? If they truly thought they were lesbians until one weird dude slipped through? No! Of course not! But then, do we let a man who has sex with men identify as straight? No, that's a closeted gay or bisexual man, that can't be allowed.

But it is. It happens all the time. Who are we to tell them to stop it? We don't live their lives. What people call themselves doesn't really seem to matter much when you hold it up to the light of their behavior, lifestyle, friend group, politics, bedroom habits, family of origin, education, internalized beliefs about themselves and others, etc. It's all useless--but it's a violence to dismiss it as useless. That's not how the politicians are thinking when they write bills that criminalize the "gay, lesbian, and bisexual" identities...or is it the gay, lesbian, bisexual behaviors? (It's both.)

Race doesn't exist, not under the microscope of biology. But you still can die for your race. But you might not know what race you are until someone kills you for it.

Growing up light-skinned in the southwest, I was always presumed white until proven otherwise. At least, that's how I always thought I was being perceived, but who knows how people were actually seeing me in the private confines of their own heads. (As if every person I met experienced me in the same way.) It startled me anytime I realized that I wasn't projecting total white girlhood, when my friends would meet my dad and say, "woah, I thought he would have more of an accent," or, "where was he born?"

Now that I'm out of my home state, when I'm alone, Spanish-speaking tourists will beeline to me in a crowded building to ask me questions in Spanish--for a bathroom, or directions, or where I got my coffee. It's touching in a way that's booted up another existential crisis. How long have I been publicly Latina? I thought that I was living an exclusively private, tender, biracial experience, invisible to everyone but me. Spending time with my mom's family and feeling too big and too brown among all of the shock-white-blonde Polish women; spending time with my dad's family and feeling assimilated, like we had permanently lost something, but at least we got to be normal and still eat potatoes. That all happened inside my head. Who gets to define my race? The individualist idea that ~only I do~ is precious, but it might get me killed. Or--it might have lost me scholarships! The number of times I shyly ticked boxes for "white" and then "Hispanic" on standardized tests, because the government teeeechnically defined me as such, even though I didn't 'feel' like it, but maybe I could 'get' something out of it, even when I didn't deserve it. I'm normal, right? Not 'other.' I'm gaming the system.

How many times were people presuming me white, but reacting to my broad, flat cheeks, my dark hair and eyes, the shape of my body, etc. with racialized bias? My kindergarten b/v speech impediment? The knit ponchos I wore in the winter? How many of my genes have been ticked on from decades of deliberate colonial violence? Is it mental illness to fear acetophenone when my great-great-great-grandmothers learned to associate it with electric shock? No? How about if it keeps me in bed all day sobbing rather than clocking a 9-to-5 and eking out a living? Is it *my* mental illness then? Is it happening inside my head or on the stage of society? Why were my bullies calling me a dyke in middle school before I myself knew I was a dyke?

All I know is that women have been calling themselves bi lesbians since Dykes to Watch Out For and that everyone who tries to sew queer infighting is a cop. :/ I don't identify as a bi lesbian, but my primary attractions have been toward women and womanhood, and almost all of my friends are or have been WLW, including many lesbians. Is calling myself "bisexual" sufficient? Is it communicating what I want, need to communicate about myself in the exact right way to every person when I need to? Does it match how people see me? When I'm with my male partner, when I'm alone on the bus reading Adrienne Rich? What am I trying to say about myself? What am I trying to do with my bisexual identity?

I wish there had been a bit more about the intersection of bisexuality and disability, or bisexuality and class, or even bisexuality outside the United States, but that last one might be beyond the scope of this book.

Some of the most salient bits of the book, for me, came from bisexuals of color:

"Maybe if I were white I wouldn't think bi is tired. Maybe it's because I don't feel a part of that vague white monolith, "The Bisexual Movement/Community." There is this tiny part of me that thinks all these white bisexuals are being really trivial in choosing bisexuality as their focus. Often I feel like biphobia exists only in white lesbians, and why should I care about them?"

I'll probably be asking myself that for the rest of my life. Thank you for giving me more to think about, Naomi Tucker et al. -

There were some really really really bad essays in here, but also some really really really great ones. I think this is a great text to just have around and I will definitely want to own it in full someday.

There is this one chapter that basically lays out how I experience bisexuality and it makes me feel so valid and seen and I love it