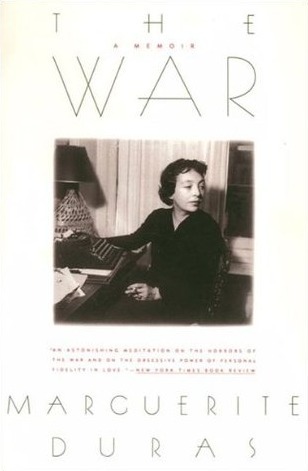

| Title | : | The War |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | - |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 192 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 1985 |

Written in 1944, and first published in 1985, Duras's riveting account of life in Paris during the Nazi occupation and the first few months of liberation depicts the harrowing realities of World War II-era France "with a rich conviction enhanced by [a] spare, almost arid, technique" (Julian Barnes, The Washington Post Book World). Duras, by then married and part of a French resistance network headed by François Mitterand, tells of nursing her starving husband back to health after his return from Bergen-Belsen, interrogating a suspected collaborator, and playing a game of cat and mouse with a Gestapo officer who was attracted to her. The result is "more than one woman's diary...[it is] a haunting portrait of a time and a place and also a state of mind" (The New York Times).

The War Reviews

-

La Douleur = The War, Marguerite Duras

War: A Memoir is a controversial, semi-autobiographical work by Marguerite Duras published in 1985 but drawn from diaries that she supposedly wrote during World War II.

It is a collection of six texts recounting a mix of her experiences of the Nazi Occupation of France, with fictional details.

She claims to have "forgotten" ever writing the diary in which she recorded her wartime experiences, but most critics believe that to be a deliberate attempt to confuse autobiography and fiction.

Duras' work is often cited as part of the New Roman movement which tried to redefine traditional ideas about set categories of books, fiction, non-fiction, biography, autobiography, etc.

تاریخ نخستین خوانش: روز بیست و دوم ماه اکتبر سال1987میلادی

عنوان: درد (جنگ)؛ نویسنده: مارگریت دوراس؛ مترجم: قاسم روبین؛ تهران، پاپیروس، سال1365؛ در169ص؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، نیلوفر، سال1378، در188ص؛ شابک9646680880؛ چاپ چهارم سال1381؛ چاپ دیگر تهران، اختران، سال1395؛ در169ص؛ شابک9789642071043؛ موضوع داستانهای نویسندگان فرانسوی - سده 20م

هیچگاه در دنیا عدالتی برپا نخواهد شد، اگر آدمی خود در این لحظه، عین عدالت نباشد؛ «مارگریت دوراس» در سال1985میلادی، کتاب «درد (جنگ)» را منتشر کردند؛ کتاب شامل شش بخش جداگانه است، که مضمون جنگ، آنها را به هم درآمیخته است

عنوانهای داستانها: «درد»؛ «پییر رابیه»؛ «آلبر دکاپیتال»؛ «میلیشیایی به نام: تر»؛ «گزنه ی شکسته» و «ارلیا پاریس» است

به گفته ی خودِ «دوراس»، اینها دست نوشته هایی هستند، که در روزهایی که در انتظار بازگشت همسر به جنگ رفته اش بوده، آنها را نگاشته اند؛ «دوراس» چهل سال بعد، بدون دستکاری و ویرایش، چاپشان میکند، و به همین علت خود را شرمنده ی ادبیات میداند

نخستین نوشته «درد» نام دارد، از روزهای طاقت فرسای پس از جنگ جهانی دوم سخن میگوید؛ از انتظار کشنده ای که «دوراس» برای بازگشت «روبر ل. - همسرش» تحمل کرده سخن میگوید

***

دومین نوشته با عنوان «پییر رابیه» نیز، از روزهایی میگوید که شوهر «مارگریت دوراس» دستگیر و زندانی شده، و «دوراس» به دنبال رابطی است که بتواند بسته ای حاوی مواد غذایی را به شوهرش برساند

***

سومین نوشته با عنوان «آلبر دکاپیتال»؛ در بحبوحه ی روزهای پس از جنگ ��هانی دوم، و تسخیر دفتر فرمانده نظامی ستاد آلمانیها در فرانسه، پیشخدمت کافه ای از راه میرسد، و به گروه پارتیزانی، که «دوراس» از اعضای آن است، اطلاع میدهد، که مردی به کافه اش آمده، که پیشترها با پلیس «آلمان» همکاری میکرده است؛ گروه به کافه میروند، و مرد مزدور را دستگیر میکنند

***

چهارمین نوشته با عنوان «میلیشیایی به نام: تر»، حکایت پسر جوانی است، که با آلمانیهای مستقر در «فرانسه» همکاری میکرده، و در روزهای پس از جنگ، توسط گروه پارتیزانی که به صورت خودمختار به دستگیری و ترور آلمانیها میپردازند، دستگیر میشود

***

پنجمین نوشته با عنوان «گزنه ی شکسته»؛ تصویر ساده و بی پیرایه ای است از باورهای کمونیستی «دوراس»؛

***

ششمین نوشته با عنوان «اُرلیا پاریس»؛ قطعه ای شاعرانه، و کمابیش شعارگونه است؛ در مورد دخترکی «یهودی» که پدر و مادرش به دست «آلمان»ها افتاده اند؛

تاریخ بهنگام رسانی 16/12/1399هجری خورشیدی؛ 12/08/1400هجری خورشیدی؛ ا. شربیانی -

First, I must confess my mistake. "La Douleur" is the text that gives the book its title, but it is not the book in itself, although it is undoubtedly the strongest of all because it is, in fact, a collection of texts.

Some lived and romanticized, others invented.

The one entitled "La Douleur" is the story of Marguerite Duras' diary as she waits - with a painful, unbearable wait even - for the return of Robert Antelme, her husband, deported to a concentration camp.

At the same time, expectation, hope, and despair are mixed. She no longer feeds and lives. She is a dead soul, a deportee by proxy.

When, finally, the unexpected, or rather the long-awaited one that we no longer expected, occurs: his return.

He is in such a state of physical decay that he no longer appears human. It's heartbreaking to read, but it is powerful. I would have liked to read more about his "reconstruction," both physical and mental. Unfortunately, we still have "L' Espèce Humaine," which says that I will certainly not fail to read it.

Another text that marked me is "Albert des Capitales." Marguerite Duras takes the skin of a character, Thérèse, but it is indeed her question. This question is because of her in the Resistance. She takes part in interrogating and torturing a donor who sold a Jew, a Resident.

Besides describing the beatings, blood, and screams, what is strong in this text questions us. First, does anything justify torturing a man? Even the worst bastard? Is it a form of justice or just barbarism like the Nazis? And then, finally, would the answers be the same in times of war if we had been in their shoes?

I found the texts quite uneven for the rest, and they missed me. Or rather, I did not know how to hang on to it.

But what does it matter? For these two texts, "La Douleur" was worth the detour. -

Published some forty years after it was written during the liberation of Paris, Marguerite Duras, with a state of mind that is clearly under the influence of paranoia, anguish, and deep worry, writes of her day to day experiences in 1944, during uncertain times in the French capital. Duras apparently found this written account as a diary in a couple of exercise books inside a cupboard, and says,

"I have no recollection of having written it. I know I did. I recognize my own handwriting, details of the story, I can see the place, and various comings and goings. But I can't see myself writing the diary. When would I have done so?, in what year?, at what times of the day?, in what house?

I can't remember."

Asked by a magazine many years later for a text she had penned during her younger days, she confronts herself with a tremendous chaos of thought and feeling to describe 'The War' as a one of the most important things in her life. Duras writes here (like some of her fictional work) using a spare, and almost arid prose, she keeps sentences brief, sometimes only two or three words long. She is continually self-involved, examining emotions and intellectual reactions to emotional states until it feels almost suffocating. It's painful, at least in the first third, which shes her husband (Robert. L) returning from Belsen a mere skeleton, more dead than alive. In fact death and dying is something Duras can't escape from, tormented, believing he will never come back, she thinks of her own death, constantly, in a state of acceptance. The original French title 'La douleur' (Suffering) would have been a far more appropriate title at this point. Nursing her love back from the brink is horrendous in detail, he can't eat properly as the shock to his body could kill him, but needs food and water as to survive, he passes a nauseating liquid waste, that has the foul, God awful stench of decomposition. But Slowly, very slowly, his condition would improve, as the lingering smell of death seems to leave his body. For Marguerite though, the love she once had for her husband, has been ravaged by the war.

The rest of the memoir looks at Duras's involvement with the French Resistance network, the brutal Interrogation of a suspected collaborator, and her run in a with the Jew hunter 'Rabier', a sly Gestapo officer who takes a liking to her, but only for his plans of gaining information on colleagues. She plays into his hands, probably for survival, and a dangerous game of cat-and-mouse endures on the streets of Paris. The book is completed with two very short fictional works whilst Duras served in the French Communist Party. 'The Crushed Nettle' is followed by 'Aurelia Paris' (which she was tempted to transpose to the stage) about a young girl hiding out in a tower with an old woman, gun in hand, simply waiting for the German police to knock on the door.

Honest, harrowing, and intense, this may not be her best work, but it is no doubt the most truthful and hard-hitting. As a fan of World War Two non-fiction I have read better, but as a Duras purest this was simply a must. For anyone that appreciates her writing it's worth a look, or for that matter an interest in life during WW2. An excellent account of a woman living through hell, but it still lacked some depth with being only 180 pages long. -

در این نوشتهها به شما زنی را معرفی میکنم که یک شکنجهگر است. این زن منم، مارگاریت دوراس. بخاطر بسپارید که اینها نوشتههایی مقدساند

درد مجموعهای از روزنگاریها و خاطرات دوراس در روزهای پایانی اشغال فرانسه بدست نازیهاست. او در این نوشتارها به مسائل حساسی اشاره میکند که قطعا انتشارش در آن زمان میتوانست منجر به بحران شود، اما بعد از گسستی 40 ساله و تغییر زمانه و ماجراهای زندگی، انتشار این مطالب ممکن شده است. پیش از خواندن این روزنگاریهای جذاب، باید چند نکته را در نظر داشت: نخست آنکه دوراس بعد از مرگ فرزندش تصمیم و برقراری رابطه با دیونیس ماسکولو، عضو نهضت مقاومت فرانسه، تصمیم به جدایی از همسرش روبر آنتلم داشت که این امر بعلت دستگیری آنتلم توسط گشتاپو تا پس از آزادی او میسر نشد. دوم آنکه دوراس پس از دستگیری آنتلم رسما به عضویت حزب کمونیست فرانسه درآمد و به یکی از اعضای فعال نهضت مقاومت فرانسه تبدیل شد. سوم آنکه چون بخش زیادی از کتاب با دستگیری روبر آنتلم در ارتباط است، خواندن کتابی که آنتلم دربارهی وقایع آن دوران نوشته (

نوع بشر) برای برقراری ارتباط هرچه عمیقتر با این نوشتار ضروری بنظر میرسد، بخصوص آنکه بخشی از وقایع در هر دو کتاب موازی یکدیگر اتفاق میافتند و این موضوع ضرورت خواندن هر دو کتاب را قوت میبخشد و البته این ضرورت بدون جذاب هم نیست. کتاب از 6 بخش تشکیل شده که 4 بخش نخست شامل روزنگاریها و خاطرات است و دو بخش کممقدار پایانی داستانهای کوتاهی که در مقایسه با بخش نخست، از اهمیت ناچیزی برخوردارند. در ادامه به موضوع 4 بخش نخست اشارهی کوچکی میکنم

درد

اشغال فرانسه بدست نازیها به پایان رسیده و اسیران سیاسی و جنگی از گوشه و کنار اروپا در حال بازگشت به فرانسه هستند. در این میان دوراس سخت در جستجوی همسرش روبر آنتلم است. دوراس ماههاست که از وضعیت همسر و خواهر همسرش بیاطلاع است، نمیداند زندهاند یا مرده و چه بر سرشان آمده. درد، روزنگاریهای دوراس از تلاشها، ناامیدیها و رنجهای این بخش از زندگیاش است. در خلال این جستجوها، معشوق دوراس، دیونیس ماسکولو هم پابهپا همراه اوست. دوراس بعد از بازگشت همسر و بهبود نسبی وضعیت جسمانیاش، از روبر آنتلم جدا میشود

آقای ایکس، ملقب به پییر رابیه

این نوشتار از نظر تاریخ وقایع، به زمانی پیش از درد بازمیگردد. روبر آنتلم توسط مامور مخفی ملقب به رابیه دستگیر و تحویل آلمانیها میشود. دوراس بطور ناخواسته وارد رابطهای ساختگی با رابیه میشود و از یک سو با کسب اطلاعات مهم و انتقال آن به نهضت مقاومت، جاسوسی رابیه را میکند و از سویی دیگر نقشهی ترور او را طرحریزی میکند. رابیه با پایان اشغال فرانسه توسط دوراس و دوستانش دستگیر و اعدام میشود

آلبر دکاپیتال

این نوشتار دربارهی یک عضو نهضت مقاومت به نام ترز است که پس از دستگیری مردی مشکوک به خبرچینی، مسئول شکنجه و اعترافگیری او میشود. ترز تا حد مرگ مرد را شکنجه میکند و در نهایت از او اعتراف میگیرد (البته دقیق متوجه نشدم که مرد واقعا مجرم بود یا تیم دوراس اشتباها او را دستگیر کرده بودند). در مقدمهی ای�� بخش دوراس میگوید که ترز نام مستعار خودش است. صداقت دوراس در بیان صریح این شکنجه و جزئیات آن جالب است

میلیشایی به نام تر

این نوشتار از نظر زمانی متاخر از باقی قسمتهای کتاب است. تمام گروههای مقاومت فرانسوی (آنارشیستها، کمونیستها، سوسیالیستها و جمهوریخواهان اسپانایی) در حال تعقیب عوامل و مزدورهای نازیها هستند. این نوشتار دربارهی یکی از دستگیرشدگان، به نام تِر است. شخصیتی سادهلوح و صادق که صداقتش تمام اعضای تیم را متعجب کرده. تر از آن دسته از افرادیست نه خواهان پول بوده و نه اعتقادی به اصول نازیسم داشته، بلکه صرفا برای ژست قدرت و بزرگنمایی اسلحه بدست گرفته و به آلمانیها پیوسته است. نه کسی را کشته و نه آسیبی به اعضای مقاومت زده. با این حال دستگیر شده و در منتظر محاکمهی صحراییست. تر یکی از شخصیتهای دوست داشتنی کتاب که حین خواندن به شدت نگران سرنوشتش بودم. دوراس در پایان میگوید اطلاعی دارد که در نهایت چه بر سر او آمده است -

Experimental and autobiographical, The War sketches a breathtaking portrait of life in Paris shortly before and after the liberation of the city from Nazi rule. In hypnotic prose Duras reflects on a few of her most vivid memories from the time: maintaining close contact with a member of the Gestapo for French intelligence purposes; waiting in suspense for her husband, a possibly executed prisoner of war, to return from a concentration camp; interrogating an informant with fellow members of the Resistance; bringing a low-level Nazi collaborator to justice. A couple of stories, rooted in fact, cap the autobiographical collection, which moves from a first-person narrative to increasingly detached pieces in which Duras disassociates from the past and frames herself in the third person, as a kind of character. The first piece is the best, but all are worth checking out.

-

کتاب مجموعهای از یادداشتها و اخبار جمعآوری شده از نویسنده است که در زمان اشغال فرانسه به دست آلمانها گرد آوری شده. او این کتاب را زمانی نوشته که در انتظار است برای بازگشت همسرش که به دست آلمانها اسیر شده.

-

Since 9/11, there has been much debate about whether torture is justified. Its apologists in the Bush-Cheney administration were eloquent about why it can sometimes be necessary. We were frequently told about ticking time-bombs and the threat of a mushroom cloud over an American city. Some horrifying stories surfaced from people who had been tortured at Guantánamo, Abu Ghraib, and elsewhere. But, and it just occurs to me now to think how odd this is, I don't recall reading one straightforward account told from the torturer's point of view.

If you're curious, you can read one here. Marguerite Duras was a member of the Resistance in wartime France. In Albert des Capitales, one of the pieces in this book, she describes in her usual matter-of-fact way an incident that occurred a few days after the Liberation. She and the other members of her cell are hanging around when a waiter comes running in and says that there's a guy at his bistro who's an informer. Everyone in his home town knows he is. But they'll have to move fast and grab him before he disappears.

So they rush into the café and arrest him. He's an overweight, unhealthy-looking guy in his 50s. He looks kind of dirty and unwashed. They make him empty his pockets. There's a notebook with names and addresses, and every so often the notation ALBERT DES CAPITALES. They want to know what this means. The guy thinks, or pretends to think, and then he says, oh yes, he's a waiter at another café, Les Capitales. He has a drink there sometimes on the way home.

Okay, says the leader of the Resistance cell, this must be his contact. We need to start rolling up the network. He immediately sends three people over to arrest Albert, but they come back empty-handed. He left days ago. They figure they'll interrogate the informer anyway. He must be able to tell them something else, and if they wait the trail will go cold. The leader asks Marguerite if she wants to lead the interrogation. Why not, she says.

They take the informer into a back room and order him to strip. He takes his clothes off slowly, hanging them up on the back of a chair so they won't get creased. One of the guys tells him to hurry up, they haven't got all day. He apologises and carries on removing his clothes. His underpants and socks are dirty. When he's naked, Marguerite asks him how to find Albert des Capitales. He answers evasively and the guys start hitting him a bit. Then Margurite asks him what he did when he visited the Gestapo headquarters. Nothing special, he says, moaning a bit and rubbing the places where they've hit him. I left my ID card at the door and went up. It was just some black market crap, nothing important.

So what color was your card? asks Marguerite, but he won't answer. They hit him, and then they hit him more, and he's bleeding in several places. She asks him again what color his card was, and he still won't answer, so they carry on hitting and kicking him. Several other people have come in to watch. A couple of women say uncertainly that maybe this is enough. The leader says that anyone who thinks it's disgusting is welcome to leave. No one leaves.

The informer's screaming and covered in blood as they kick him around like a ball. But he still won't say what color his card was. Marguerite tells him he'd better answer or they'll kill him. It looks like she means it. She tries different possibilities. Was it white? He moans no. Red? Also no. Yellow? No again.

In the end, he screams out that it was green. That's the color that means he's an S.D. secret agent. Marguerite tells the guys to stop torturing him and let him put his clothes on. She goes out and sees a woman who'd missed all the fun.

He confessed, says Marguerite. So fucking what? shrugs the woman. Marguerite starts crying. We should just let him go, she says. People won't like that, says the cell leader.

She didn't get around to publishing this story until 1985.

_______________________________________

The "green card" plays an important role in Simenon's La Neige Etait Sale. It becomes clear that anyone who had a green card was a tool of the Nazi occupiers, and could legitimately be regarded as the worst kind of collaborator and traitor. -

A collection of 6 short stories, of which at least 2, possibly 3, are autobiographical. Duras claimed they were written shortly after World War II, but totally forgotten by her; they were not published until 1985. Especially the first story ("La douleur"/literarly "The Suffering", but the English editor chose "The war")is a real punch in the stomach, I cannot describe it otherwise. Set largely in April-June 1945, it describes the state of expectation, despair and feverish confusion of a woman in Paris (clearly Duras herself) awaiting the possible return of her husband Robert from a German concentration camp. The description of Robert's fragile state and his dire recovery are particularly gripping. Since Primo Levi's

If This Is a Man no other story on the camps captivated and shocked me like this one.

The second story apparently also is based on true facts. It describes Duras’ dealings with a Gestapo employee while she is active in the resistance, after her husband has been arrested. It poignantly sketches the atmosphere of uncertainty at the end of the war, and the twilight zone in which the resistance had to operate. The third story evokes the resistance's brutal questioning of a possible French collaborator; especially the raw style is striking in this one. The other stories are fictional and seem more like style exercises than full-blown short stories. A memorable booklet!

(side note: apparently the resistance movement Duras and her husband were part of, was led by the later president François Mitterrand; he is mentioned a few times) -

Reviewed in conjunction with

Roughneck by Jim Thompson

Sometimes you read a book that makes you feel ashamed of your life, every time you thought you were unlucky or that you deserve more or that you should get more. Whatever you have suffered, however genuine it be, suddenly becomes as nothing, its place clearly fixed in the universe as the measliest dot the world ever has seen. Roughneck does that. It describes a portion of his life in the pared down, straightforward way Thompson tells all his stories. Nothing is oversized, filled with extra words so that you can feel like you are getting more than you paid for. You are, of course. But not in word count.

As is so often the case, the small story about a few, packs so much more punch than big numbers. This one starts before the Great Depression and takes us through that period. Not that I should be calling it a story. I groaned when I realised I’d picked up an autobiography, not a novel. Live life, don’t read about others, p-llllease. But I was too mean not to read it, serves me right for not looking carefully when I bought it. And before two pages were up I was goggle-eyed, gaping-mouthed hooked.

The man’s a genius. He can even make biography bearable. I’m not going to review this, for the simple reason that I’m not worthy too. The human suffering he writes about, what Americans did to Americans, even white Americans to white Americans, would be demeaned by anything I said about it. I don’t think I ever realised so clearly the extent to which poverty and wealth create the same barriers, the same hate as race or religion, maybe even worse. Watching the way wealthy Americans treated those they were exploiting in this period made my stomach churn. I think that’s the most incredible aspect of it. It is so easy to understand poor people might hate rich. But this book brings home the other side of this and it is truly ghastly to watch.

This is a wildy entertaining book, but it is about people who were rich, watching, exploiting and being despicable to their poor neighbours. It is about people unnecessarily half starving, living in the most desperate circumstances and heart in mouth hoping they pull through. It makes you ashamed to be human.

So I thought.

But then, I hadn’t picked up La Douleur yet.

‘Shit.’ That is what I did say out loud, irritated when I picked this up, the very next book after Roughneck. Another hasty purchase, another %$^#$ autobiography. A slightly wanky one, if it comes to that, I felt as I started it – after the plain matteroffactness of Thompson, Duras seemed on the hysterically dramatic side.

Then again, who wouldn’t be? Thompson writes about the half starved. Duras writes of the 95% starved. I don’t know how to put that. People who are literally skin and bones as they come back, those few who do, from the camps of Nazi Germany, people who are so close to death that food is going to kill them as surely as lack of it will, people whose skeletons can’t bear the tiny weight on them. I have no way of describing the horrors recorded here and to quote bits and pieces would seem plain disrespectful.

I did need some pages to adjust to the girly, introspective way Duras sets out her story here, but then, it was never supposed to be a story, not like that. It was what she wrote at the time for herself, trying to hang on to what was left of her sanity as she waited for her husband to come back during the period in which the prisoners were set free from the Nazi camps. She has some moments of marvelous acidity as she describes how some of the French take advantage of the new political situation. She is no friend of de Gaulle, who sounds like a right creep the way she tells it.

It turned out that being ashamed of America in the Depression wasn’t the half of it.

Lately I seem to keep on – completely coincidentally – reading books that pair each other in some significant way and here again, it’s happened. It’s an odd request, but I’m making it. These books go together. Get them and read them back to back. It’ll be totally worth it, I promise!

Afterthought:

I went to see de Santiago Amigorena's Another silence recently and it deals, as does Duras, with the issue of revenge. What a fine contrast. The heroine, whose husband and child are murdered, sets about revenge as coldly as does Duras in the story where she talks about torturing a collaborator, but in the end, faced with the perpetrator, a piece of Argentinian trash, she not only can't kill him, but she even grants him a gesture of mercy. The difference? Maybe that in Another Silence she meets the wife and child of the killer of her family. Maybe Duras is able to torture people with the objectivity of principle because her victim doesn't look human.

Then again, maybe it is part of her own terrible guilt. It transpires that Duras - all the time she was suffering in such a melodramatic way that she confesses 'D' chastises her and points out she should be ashamed of how she is behaving - is in love with 'D' and planning to tell her husband as soon as she can, if he comes back, that she wants a divorce. No wonder she has to behave as if she is suffering all that he is, even though she can only play at that.

I don't think this detracts from the book, it simply adds a layer of human behaviour which may repel the reader, but is no less readable for that. -

★★★★☆

Este libro es un pequeño recopilatorio de algunos textos que escribió Marguerite Duras durante 1944. La gran peculiaridad es que ella ni siquiera recuerda haberlos escrito y los encontró años más tarde en una especie de diario que decidió publicar.

En esta obra autobiográfica, la autora nos relata las semanas previas y posteriores a la encarcelación de su marido, su paso por un campo de concentración y su esperada liberación. Asimismo también conoceremos su testimonio formando parte de la resistencia en Francia, cómo tuvo que afrontar situaciones aterradoras con tal de sobrevivir.

Es sumamente angustiante leer a Marguerite, su narración ahonda en la penuria, en el desespero y en el tormento en el que se ve sometida al vivir este calvario. Es una lectura desgarradora que nos muestra el dolor y temor que tuvieron que sufrir los que se quedaban en casa esperando a sus familiares.

La falta de información resulta uno de los principales motivos de desespero, no saber dónde están sus seres queridos y la lucha que deben seguir afrontando desde sus hogares. En uno de los relatos además nos explica la obsesión que tenía el agente de la Gestapo que detuvo a su marido con ella.

Considero que esta novela es un testimonio muy valioso de una mujer que se sintió morir y que se arrastró por la vida sin esperanza. En algunos momentos resulta confusa, pues son frases soltadas a bocajarro que nacen de la emoción y del sufrimiento. Estoy deseando seguir leyendo a esta maravillosa escritora. -

https://kansasbooks.blogspot.com/2024...

“De los hombres que he conocido, es el que mayor influjo ha ejercido sobre las personas de su entorno, el hombre más importante en cuanto a mí y en cuanto a los demás, explicará Marguerite. -No sé cómo decirlo. No hablaba y hablaba. No daba consejos, pero no se podía hacer nada sin su opinión. Era la inteligencia misma y aborrecía parecer inteligente al hablar. “

(Marguerite Duras sobre Robert Antelme)

“Cuando me hablen de caridad cristiana, responded Dachau.”

(Robert Antelme)

Ya he contado por aquí en otras reseñas que hasta ahora mi relación con Marguerite Duras había sido puramente cinéfila, sin embargo, esta fiebre por sus textos comenzó con “El Arrebato de Lol V. Stein”, y casi se podría decir que fue también un arrebato lo que me condujo a ahondar en sus textos: la Marguerite Duras cineasta se me desplegaba bajo otra perspectiva, y cuando comencé la magnifica biografía de Laure Adler, lo que empezó siendo un tanteo, se ha ido convirtiendo en un descubrir poco a poco sus textos a medida que Adler los va analizando relacionándolos con sus vida. Marguerite no fue una mujer fácil: ambigua, subterránea, imagino que por todo lo que le tocó vivir que la obligó a protegerse, a disfrazarse, a enmascararse, y tal como dice Laure Adler:

“En la pantalla negra de sus deseos, Marguerite, más adelante, sabrá plasmar en sus films los desasosiegos de sus heroínas. No olvidemos que con Marguerite siempre andamos metidos en películas. ¿Dónde está el mundo de verdad? ¡Se ha montado tantas películas que nos han adormecido con sus mitos familiares, con sus sueños de princesa de culebrón televisado, con sus alucinaciones más bonitas que la siempre triste realidad." (Laure Adler)

Así que aunque este texto, El Dolor, aparezca como unas memorias, hay que andarse con mucho tiento con Marguerite Duras, porque nunca sabremos hasta qué punto es veraz lo que cuenta, aunque ella en el prólogo advierte que este texto no es una transcripción de sus diarios o cuadernos. La revista Sorcieres le encargó un texto de juventud, y así fue como ella buceando en sus armarios, llegó hasta estos cuadernos, según ella olvidados en un rincón. No sabemos hasta qué punto había querido arrinconarlos para olvidar esta experiencia, pero encontrarlos, y abrirlos fue todo un mazazo para ella, así que como cuenta Laure Adler, más que releerlos, fue como si los leyera por primera vez. Los cuadernos fueron escritos entre 1944 y 1945 cuando Robert Antelme, su marido, fue arrestado por los nazis por pertenecer a la Resistencia y enviado a un campo de concentración. Marguerite garabateó en sus cuadernos durante la espera, la durísima espera, en plena ocupación alemana, y no fue hasta cuarenta años después, en 1985, que estos diarios no vieron la luz en forma de recomposición literaria, en un título que no puede definir mejor, todo lo que expresa Marguerite Duras en ellos. Algunos críticos pusieron en su momento en tela de juicio la veracidad de lo que se cuenta en El Dolor, y puede ser cierto porque el tiempo difumina los recuerdos, así que Marguerite Duras contará lo que recuerda y en todo caso estará en su derecho a seleccionar lo que quiere contar, pero ya digo que no es fácil desnudarse, dejarse la piel en un escrito como éste: “Gritaba. De eso me acuerdo. La guerra salía en mis gritos. Seis años sin gritar.”

“Me he vestido. Me he sentado junto al teléfono. D. llega. Exige que vaya a comer al restaurante con él. El restaurante está lleno. La gente habla del final de la guerra. No tengo hambre. Todo el mundo habla de las atrocidades alemanas. Ya nunca tengo hambre. me revuelve el estomago lo que comen los demás. Quiero morir. He sido cercenada del resto del mundo con una navaja de afeitar. El cálculo infernal: si no tengo noticias esta noche, ha muerto.”

El Dolor está dividido en dos partes, por una parte, en la primera que lleva el mismo titulo, Marguerite Duras logra transmitir la ansiedad de la espera en la guerra y el sufrimiento que conllevaban las largas colas, la desinformación sobre si los prisioneros seguían con vida o no, párrafos que me remitían una y otra vez a "Sofia Petrovna" e "Inmersión· de Lydia Chukovskaia. Robert Antelme, su marido, del que ya se había separado pero cuyo vínculo era tan fuerte que durante esta separación ninguno dejó de pensar en el otro y ambos olvidaron que se habían dejado mutuamente, así que el texto está escrito como si nunca se hubieran dejado, una ausencia que reafirmó el lazo. El vínculo entre ambos era tan fuerte, que Marguerite no dejó ni por un momento de buscar y dejarse la piel, lo que enlaza esta primera parte con la segunda parte del relato titulado “El señor X. Aqui llamado Pierre Rabier. En esta segunda parte, se describe el juego de Marguerite Duras con Pierre Rabier, un oficial de la Gestapo que traba amistad con ella con la excusa de su admiración por sus escritos. Es un juego del gato y el ratón el que se trae Marguerite con este colaboracionista que admira a los nazis y llegado un punto no sabremos quién juega con quién. Él la engaña haciéndole creer que sabe dónde se encuentra su marido y no sabremos hasta qué punto ella lo cree o lo ha desenmascarado desde un primer momento, el caso es que la relación de Marguerite con este nazi fue uno de los puntos negros de su pasado. Rabier miente y se miente a sí mismo porque ha creado un personaje, exagera su cargo, su importancia pero para Marguerite será la única esperanza de poder saber dónde se encuentra Robert Antelme, si está vivo o muerto, es casi la única conexión que le queda con Robert, un agarrarse a un último hierro ardiendo. Marguerite Duras además jugó con fuego durante su relación Rabier y da la impresión de que dado que era una muerta en vida durante la desaparición de Robert, el miedo que sentía en sus encuentros con Rabier era lo único que la mantenía viva: : “El tipo de miedo que yo vivo con Rabier desde hace tiempo, el miedo de no saber hacer frente al miedo.”

“¿Qué es toda esta historia? ¿Quién es? No más dolor. Estoy a punto de comprender que ya no hay nada en común entre este hombre y yo. Yo ya no existo. Así pues si ya no existo ¿a qué esperar a Robert L.? ¿Quién es Robert L.? ¿Ha existido alguna vez? ¿Qué hace que le espere a él, precisamente a él? ¿Que es lo que ella espera en realidad?”

Las frases breves, directas, secas y sin adornos son el acercamiento perfecto a este horror que nos narra una Marguerite desde lo más íntimo de su ser. No solo nos transmite esa atmósfera de esa Francia ocupada en la que todos eran sospechosos y cualquiera podía ser arrebatado de su hogar para ser llevado a un campo de concentración, sino que Marguerite Duras narra como nadie ese terror íntimo de una espera que no tiene fin, ese quedarse a solas con ella misma y no poder soportar el dolor. Cuando imagina a Robert Antelme es siempre muerto, en una zanja, nunca vivo, quizás porque no quería permitirse el lujo de la esperanza. Marguerite exorciza ese dolor escribiendo al igual que lo hizo Lidia Chukovskaia en su momento, pero en el caso de Marguerite Duras, estos diarios eran demasiado dolorosos para hacerlos públicos. Dijo que no recordaba haberlos escrito y sin embargo, le parecían lo más poderoso que había escrito nunca. Los cuadernos existen.

“Está noche pienso en mi. Nunca he encontrado una mujer más cobarde que yo. Recapitulo, de las mujeres que esperan como yo, ninguna es tan cobarde. Conozco algunas muy valientes. (Incluso ahora, al retranscribir estás cosas de mi juventud, no capto el sentido de estas frases.) Ni por un segundo veo la necesidad de ser valiente.

Así pues estoy sola. Por qué economizar fuerzas en mi caso. No se me ha propuesto lucha alguna. La que llevo a cabo, nadie puede conocerla. Yo lucho contra las imágenes de la cuneta oscura. Hay momentos en que la imagen es más fuerte, entonces grito o salgo y ando por París. Las mujeres que hacen cola para comprar cerezas están a la espera. Yo estoy a la espera."

♫♫♫

Sinerman - Nina Simone ♫♫♫

La douleur , 2017, Emmanuel Finkiel -

Estoy escribiendo sobre el dolor y recordé que este libro está en mi estantería. Un profe del magíster, en 2013, me dijo que lo leyera. Mi papá me lo prestó. Nunca se lo devolví. Es un libro sobre el dolor de la muerte y me lo prestó mi papá que murió hace tres meses. Segunda vez que lo leo y significó distinto. Igual que un viaje a una ciudad, aunque la conozcas, dependerá de la etapa de la vida en que estés lo que reconozcas, lo que llame tu atención. Ahora el libro es mío, no tengo cómo devolvérselo a mi padre.

Los tres primeros capítulos son desgarradores. Uno habla de la espera de un cuerpo viviente que regresa de un campo de concentración y cómo de a poquito ese esqueleto con pellejo andante vuelve a ser un humano. La espera, la incertidumbre de la muerte y el dolor de ver un cuerpo que resiste a morir|vivir luego de un episodio de tanta carencia es estremecedor. Sentí en el cuerpo un poco de su dolor, de su asco, de su nervio. El segundo es una relación de amor odio, de cacería y seducción, entre Marguerite Duras y un agente de la Gestapo. Salen a comer, se cuentan su vida, pero sobre todo, se marcan, se mean: cada vez que se reúnen es la resistencia y la policía nazi quienes juegan al equilibrio de su existencia. Es como la broma asesina de Batman y el Joker. El tercer episodio es el relato de un proceso de tortura. Marguerite Duras lideró la tortura de un sapo, de un soplón, del bando contrario a la resistencia. Y el dolor ahí es un relato salvaje. Marguerite Duras dice: sólo el dolor le va a sacar la verdad, así se hará justicia, somos la justicia, somos dios. Una persona golpeando hasta morir a otra en nombre de la justicia, en nombre de reconocer la verdad, en limpiar la mentira. Es escalofriante. Los dos últimos relatos son ficción y también son de miedo y muerte, pero ahí ésta corre por debajo, como el iceberg de Hemingway o el segundo cuento de Piglia, es algo que no se ve, pero acecha inminente. Los relatos de no ficción son impactantes por eso, porque la muerte, el olor de la sangre, la traición y el secreto están en primer plano, y esa explotación, esa evidencia feroz, para mí es inigualable. -

Sou apaixonada por literatura de testemunho, então sabia que ia adorar essa leitura. Duras escreve sobre o período da segunda guerra mundial, mas de uma forma muito inédita pra mim. Como mulher, como militante e sobrevivente.

“A dor é uma das coisas mais importantes da minha vida”.

Achei genial que esse livro transcende a autobiografia, e sim passeia por outros gêneros, como autoficção e até mesmo ficção. -

من چقد باید با روایت ها و داستانای جنگ جهانی دوم گریه کنم؟به اندازه ی درد تموم اون آدما؟....

داستان آخر منو عجیب یاد فیلم فهرست شیندلر انداخت...اون دختر کوچولوی سرخ پوش...

این کتابو ازدست ندید.بخاطر تموم تجربه هایی که بهتون اضافه میکنه. -

روایت دوراس از رنج جانبهدربردگان ِجنگ، فلجکننده است. نمیفهمم چطور چنان حال و تجربهی توصیفناپذیری را اینطور قوی و شگفت توانسته بر کاغذ بیاورد

-

Raccolta di racconti che ruotano intorno alla fine dell'occupazione nazista in Francia ed il periodo successivo, soprattutto il primo é degno di nota: la scrittura autobiografica dura e dolorosa rende l'attesa per il ritorno del marito deportato qualcosa di palpabile ed angosciante.

-

مارگریت دوراس رو اصلا نمیشناختم و برای آشنا شدن باهاش این کتاب رو برداشتم

ماجرا مربوط به زنی فرانسویه که همسرش رفته اردوگاه کار اجباری جنگ جهانی دوم. روایت جالبی بود. همیشه از مصیبتهای داخل اردوگاه خوندیم، این دفعه از مصیبتهای چشمانتظاران.

البته توی دو بخش انتهایی کتاب یه کم با فضای بعد از آزادی فرانسه هم روبرو میشیم که جالبه ولی قوی نیست

کلا بدم نیومد از دوراس ولی خیلی هم تحت تاثیرش قرار نگرفتم، باید یه کم بیشتر ازش بخونم -

"Not for a second do I see the need to be brave. Perhaps being brave is my form of cowardice."

I just realized that I have not reviewed this book yet.

Part of the reason for my lapse is that there is never anything to say about war. About the Holocaust. About torture. About death.

Or rather, there is too much to say that I never know where to begin.

Besides Marguerite said it all already in this book.

Which is in itself impressive. She says it all in here without falling into the typical trappings of saying it all about such a subject.

Without sentimentality. In fact with the opposite of sentimentality."There's no point in killing him. And there's no longer any point in letting him live. ... And just because there's no point in killing him, we can go ahead and do it."

She goes to the very edge of emotional experience and is somehow able to write about it almost as it was going on, and it doesn't turn out like an overly emotional teenager's drivel (I just realized after I wrote this that it may be read as a subtle criticism of Anne Frank, but it's not intended that way, I haven't read her since high school, so can't speak on that front).

Part of the reason this is impressive is that to go to the very edge of emotional experience is an entirely different beast than to write out that experience on paper. To affect a reader in that way requires going to a different place inside of oneself after much silence, quite separate from the edge of experience that is experienced while in the midst of experiencing the edge of experience.

Duras was able to do that seemingly in the moment. At the edge and not at the edge at the same time. How?

Maybe the war divides us, divides our experience, so that we can talk about the missing cheese in the same sentence as we talk about the death of a traitor (as they do in one of the later chapters here).

Death and cheese, Duras understood, normally existed on different planes of human experience. But in wartime there is only one plane of human experience. Human experience becomes one dimensional. There are no hierarchies of objects. Everything is simultaneous."I feel a slight regret at having failed to die while still living."

-

Margareth Duras is a long poem, in different books with different verses.

با نام دوراس "سوزان سونتاگ"، و با نام سونتاگ، "مارگریت دوراس" تداعی می شود. تصور می کنم دوراس را هر زنی باید بخواند، و البته هر مردی هم. دوراس "سیمون دو بوار"ی دیگر است، با همان بی پروایی، جسارت و صلابت، اما زنانه و ظریف. برای خواندن و فهمیدن دوراس، باید حوصله و دقت داشت، همان اندازه که برای خواندن ویرجینیا وولف. بسیاری از آثار مارگریت دوراس به همت قاسم رویین به فارسی برگردانده شده. "تابستان 80"، "بحر مکتوب"، "درد"، "نایب کنسول"، "نوشتن"، "همین و تمام"، "باغ گذر"، "باران تابستان"، "عاشق" و البته یکی از شاهکارهایش "مدراتو کانتابیله" توسط رضا سیدحسینی ترجمه شده و "می گوید؛ ویران کن" را خانم فریده زندیه به فارسی برگردانده است. تا آنجا که یادم هست، "هیروشیما، عشق من" نیز سال ها پیش و احتمالن توسط "هوشنگ طاهری" به فارسی ترجمه شده. کتابی که دیگر هیچ خطی از آن به یادم نمانده با این نام، صحنه های فیلم "آلن رنه" با بازی "امانوئل ورا" در خاطرم زنده می شود، فیلمی که در 1959 بر مبنای این رمان کوتاه دوراس، ساخته شده است.

این اثر دوراس هم مانند اغلب آثارش در فارسی، توسط قاسم روئین ترجمه و در سال 1378 منتشر شده است -

خانم مارگاریت عزیز؛ چند شب پیش بود که زدیم توی پر هم. بعد از آن می خواستم به دوراس خوانی فاصله ای بدهم. اما نمی دانم چه شد که کتاب درد را شروع کردم. داستان-کوتاه بلند درد و داستان کوتاه پیر رابیه تان حرف نداشت. می دانید خانم دوراس! باز همان احساس گناهی را دارم که بعد از خواندن صفحه ی آخر وداع با اسلحه داشتم. باز همان شرمندگی حاصل از حیرت صحنه ی پاره شدن دل و روده ی اسب رمان در جبهه ی غرب خبری نیست بیخ گلویمان را گرفت. احساس گناه از این که لذت می بری از خواندن داستانی که قساوت بشر را می کوبد توی صورتش. شرمندگی... شرمندگی... خانم مارگاریت عزیز! هنوز یادم نمی آید که خاطره یا داستانی نظیر دردتان خوانده باشم که تویش این چنین مجروح جنگی به مثابه ی یک ضایعه ی جنگی تصویر شده باشد؛ ضایعه ای چنان اسف بار که خیلی واقع بینانه و سرراست گند بزند به انتظار. بله خانم مارگاریت، چقدر خوب تصویر کرده اید انتظاری را که هیچ وقت نباید به سر می رسید. چقدر خوب ما را در این موقعیت تحقیرآمیز قرار داده اید. شما آدم بزرگی نیستید، اما شاید بزرگی تان در همین جسارت تان باشد که نمی خواهید خودتان را از آنچه که لایقش هستید بزرگ تر نشان دهید. برای دوست داشتن یک زن چه چیزی بیشتر از این؟

-

Δεύτερο βιβλίο της Duras μετά το "Ο εραστής". Σε αυτό το βιβλίο το backround είναι η Γαλλία με τη συγγραφέα να μοιράζεται τις -ως επί το πλείστον- αληθινές ιστορίες της γύρω από τη γερμανική κατοχή.

Η Γκεστάπο συνέλαβε τον σύζυγό της και στο βιβλίο αποτυπώνεται,μεταξύ άλλων, η προσπάθειά της μέσω της Γαλλικής Αντίστασης και του Κομμουνιστικού Κόμματος να τον βρει. Κάπου είχα διαβάσει, μάλιστα,ότι η ίδια αποφάσισε να τότε να μην γράψει λέξη και δεν δημοσίευσε τίποτα απολύτως μέχρι το 1950. Το κοινό με τον "Εραστή" είναι ότι -κατ' εμέ- "τρέχει" μια παράλληλη ιστορία στο προσκήνιο, αυτή της χειραφέτησης της Duras.

Το βιβλίο αυτό έγινε ταινία το 2017 (;) και χαίρομαι που το διάβασα, γιατί η ταινία δεν ήταν αξιόλογή του (αν σκεφτεί κανείς, δε, ότι μιλάμε για τη σεναριογράφο του μοναδικού "Χιροσίμα, αγάπη μου"...).

Τελοσπάντων, η Duras, χωρίς να με εντυπωσιάζει ή να με κάνει να τη συγκαταλέγω σε νοητές λίστες αγαπημένων συγγραφέων, νιώθω ότι μου ταιριάζει... -

The great sundering of 20th century Europe in all its visceral brutality, through a series of narrow cases. A waiting for word of the dead or maybe living, a forced desperate proximity to a traitor (quintessential embodiment of the banality of evil -- he failed to open an art book store, so became an official for the collaborationist government), an interrogation, a few thematic vignettes. Through these, Duras traces the contours of something inexpressible. My question for any 20th-century French author is: what were you doing during the occupation? Duras, here, tells us: she was in the resistance, trapped in Paris with mortal enemies, at great personal risk. My respect for her increases; the sometimes amorphous black desperation of all of her subsequent writings gain new depth and teeth of reality. (Corollary question: what am I doing during the occupation of the USA? Not enough.)

-

"Ho ritrovato questo diario in due quaderni negli armadi blu di Neauphle-le- château. Non ricordo di averlo scritto. So che é opera mia, sono stata io a scriverlo, riconosco la calligrafia e i particolari del racconto, rivedo il luogo, la stazione d'Orsay, gli spostamenti, ma non mi vedo nell'atto di scrivere questo Diario. (...)

Il dolore é fra le cose più importanti della mia vita. La parola 'scritto' qui stonerebbe. Mi sono trovata davanti a pagine uniformemente piene di una calligrafia minuta, straordinariamente regolare e calma. Mi sono trovata davanti a un disordine formidabile del pensiero e del sentimento che non ho osato toccare, e davanti al quale mi vergogno della letteratura. " -

In so many ways, this is a novel unlike anything else Duras has written-- it's far more straightforward, especially considering how it masks itself as a series of “lost diaries.” And it's skeletally spare, which I think is necessary when you're writing a book called “La Douleur” (“Pain”) (and a major fuck you to whichever American publisher decided to translate this title as “War: A Memoir”). While it doesn't reach the tropical lushness of L'Amant or the spare beauty of Moderato Cantabile, it's still Marguerite Duras. You can't go wrong.

-

Hard to believe this wasn't published until the 1980s, when Duras found the material in an old attic and had little memory of having written it. Highlights are the two opening sections: Duras's astonishing account of waiting to see if her husband would return from the concentration camps and her encounters with the German officer who arrested him.

-

Le journal de Duras, alors qu'elle attendait le retour de son mari des camps de concentration. L'angoisse de la narratrice est palpable, le tout avec le style si particulier, haletant, de Duras. Bref, marquant.

-

Margerit Diras je pred kraj života uglavnom objavljivala autobiografsku prozu. Svodila je životne račune. U tom svođenju, u odabiru toga šta će biti ispričano, šta prećutano, a šta zaboravljeno, gradila je svoju poslednju junakinju, fiktivnu Margerit Diras, literalnu masku u koju neće poverovati samo njeni čitaoci, već i ona sama.

Dok je stvarala svoju poslednju junakinju, Diras je, čitajući svoje stare sveske, znala da zabeleži na marginama: Da li je ovo Diras? Ovo ne zvuči kao Diras, i sl. Jedan od rezultata kopanja po starim sveskama bio je i BOL, knjiga sačinjena od 6 proznih, mladalačkih, autobiografskih tekstova o Drugom svetskom ratu. Svaki od njih propraćen je njenim kratkim uvodom koji lokalizuju opisani događaj u njenoj biografiji.

Čitaoci koji se nisu navukli na njeno ispovedno pisanje, verovatno mogu Bol da preskoče. Oni koji su se navukli, Bol ne smeju nipošto da propuste. Prvenstveno jer se Dirasina ispovest ovde ne tiče isključivo ličnog, već privatne traume dobijaju jedan određeni istorijski okvir Drugog svetskog rata i Dirasine anagažovanosti u levičarskom krilu Pokreta otpora. Narcisiodna zaljubljenost Dirasinog ja, ovde zna da se povuče i da se vrlo pronicljivo zagleda u drugo biće, pokušavajući da odgovori na pitanje šta je čovek u ratu.

Rečenice su kratke. U knjizi imamo čitave pasuse koji su ispisani rečenicama od samo tri reči. Snažan efekat ne izostaje, bilo da govorimo o sećanju na Dirasino krvavo isleđivanje kolaboracioniste ili o sećanju na igru mačke i miša sa vojnikom gestapoa koji je bio odgovoran za hapšenje njenog muža. Ipak, najsnažniji utisak ostavlja opis dolaska njenog supruga iz koncentracionog logora i tih 17 dana, koliko traje borba za njegov živiot. Kostur od 38 kilograma, neprepoznatljiv svima, sveden na prizemnost opstanka života. Prizemnost borbe ogoljena na rad creva, na njegovu stolicu, mirise i zvukove koje ispušta. Uznemirujuće u svojoj sirovosti, sublimirano u svojoj životnosti. -

El Dolor de Marguerite Duras, edita Alianza

"el dolor es una de las cosas más importantes de mi vida".

El dolor es una re-escritura basada en unos cuadernos que Duras escribió entre el 44-45, con motivo de la detención de su compañero Robert, quien fue deportado a Dachau.

El dolor es un libro descarnado, es una lectura cruda, una lectura que te aplasta, que me ha hecho parar en varios momentos y por describirlo de algún modo poético o siguiendo a la propia Duras, he buscado el cristal frio de la ventana donde apoyar la frente.

Momentos de confusión por la detención de Robert, de no entender al hombre, de odiar a toda una población y desear su exterminio. Momentos de dolor, de vigilia, de hambre de sueño, cuando tu ya no formas parte de ti por esa espera que te lleva al extremo.

"desde hace tiempo no tengo sueño me despierto y entonces se que he dormido (…)no es corriente esperar así, yo nunca sabré nada, solo se que el tuvo hambre durante meses y que no volvió a ver un pedazo de pan antes de morir".

Una mujer que espera a un hombre que ya no ama, una mujer que duerme al lado de un cuerpo tirado en una cuneta.

El dolor es un libro crudo, es un libro de un realismo bestia. Las descripción del aspecto de Robert cuando por fin termina esa espera es tan tremenda, tan real

"Durante diecisiete días el aspecto de esa mierda ha seguido siendo el mismo. Diecisiete días sin que esa mierda se parezca a nada conocido. Diecisiete días escondiendo a sus propios ojos lo que sale de él".

El dolor es una jodida maravilla de lectura que además viene acompañada de otros 5 textos que no son menos interesantes. Como la tortura a un chivato infiltrado en la resistencia llevada a cabo por la propia duras o su relación con un oficial de la gestapo para sacar información sobre el paradero de Robert.