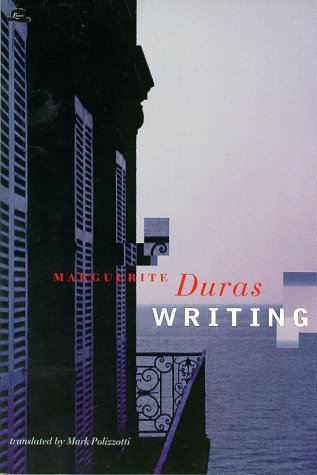

| Title | : | Writing |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1571290532 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781571290533 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 91 |

| Publication | : | First published September 15, 1993 |

Writing Reviews

-

Las frases lentas, esas frases pausadas, que lleva y extiende, repite, se extiende en el silencio, igual que en lo que dice. La manera en que Duras cuenta, no tiene nada que ver con nadie. Estos relatos fueron pensados para contarse frente a una cámara, filmando a Duras. Siempre su cercanía con el cine, con la imagen. Siempre una belleza. Todo lo que escribe esta mujer, incluso cuando habla sobre la soledad para escribir, es hermoso.

-

#WITMonth

Silêncio. Ela retoma:

- Veja a grande fonte central. Dir-se-á que está gelada, lívida.

- Estava a olhá-la... Está iluminada à luz eléctrica, dir-se-ia que flameja no frio da água.

- Sim. O que você vê nas dobras da pedra são os leitos de outros rios. Os do Médio Oriente e de muito mais longe ainda, na Europa Central, os leitos do seu trajecto.

-E estas sombras sobre as pessoas.

- São as das outras pessoas, daquelas que olham os rios.

- Roma -

Como leitora, não tenho um plano definido nem caixinhas em que queira pôr um check, mas há alguns autores cuja bibliografia gostaria de conhecer por completo. Essa lista é encabeçada por Marguerite Duras, que comecei a ler bastante nova graças a uma querida professora de História, que entre Guerras Liberais e Domínio Filipino, ainda tinha tempo para nos falar de autoras incontornáveis. Contudo, o rol de livros desta autora parece interminável e cruzo-me constantemente com títulos que nem sabia que existiam, como este “Escrever”, que congrega cinco textos: “Escrever”, “A Morte do Jovem Aviador Inglês”, “Roma”, “O Número Puro”, “A Exposição de Pintura”, naquele estilo fragmentado e solipsista que a define.

O primeiro ensaio foi de longe o mais interessante para mim e é nele que a autora fala da solidão, a verdadeira solidão física, que lhe foi necessária para escrever “O Vice-Cônsul” e a “A Ausência de Lol. V. Stein”

Não encontramos a solidão, fazemo-la. A solidão faz-se só. Eu fi-la. Porque decidi que era aqui que deveria estar só, que estaria só para escrever livros. Passou-se assim. Estive só nesta casa. Fechei-me aqui – também tive medo, evidentemente. E depois amei-a. Esta casa tornou-se a da escrita. Os meus livros saem desta casa. Desta luz também, do parque. Desta luz reflectida no tanque. Precisei de 20 anos para escrever isto que acabo de dizer.

Não é um quarto só seu; é toda uma casa. Sobre essa casa de Neuphale, comprada com os direitos de adaptação ao cinema de “Uma Barragem contra o Pacífico”, Duras conta vários pormenores, desde o jardim que a rodeia aos amigos que recebia, passando por um episódio estranhíssimo com uma mosca na despensa, mas é quando se debruça sobre o seu mester que as palavras fazem mais sentido, como esta passagem, que explica muita da frustração que sinto com livros que me desiludem.

Creio que é isso que eu censuro aos livros em geral: o facto de não serem livres. Vemo-lo através da escrita: são fabricados, são organizador, regulamentados, poderíamos dizer, conformes. (...) O escritor, então, torna-se no seu próprio chui. Quero dizer com isso a procura da boa forma, quer dizer, da forma mais corrente, mais clara e mais inofensiva. Há ainda gerações de mortos que fazem livros pudibundos. Mesmo os jovens: livros encantadores, sem qualquer prolongamento, sem noite. Sem silêncio. Por outras palavras, sem verdadeiro autor. Livros diurnos, de passatempo, de viagem. Mas não livros que se incrustem no pensamento e que digam o luto negro de todas as vidas, o lugar-comum de todos os pensamentos. -

Uhhhhhh. I didn't get it but the prose was hypnotic nonetheless.

-

A rather slight piece containing what appears to be some of the thoughts floating about in Duras' head on the subject of writing, circa 1993. These tend to take the form of short paragraphs or single lines, though two at least become vignettes and "chapters" of a sort. Overall, the work gives the impression of the sort of notes you might write when preparing to give a speech where you want just the right phrase- attacking and re-attacking a single idea from different angles.

At first, Duras' thoughts focus (loosely) around the country house she writes in and the "solitude" she finds there, both literally and figuratively. It's reminiscent of A Room of One's Own, really, only less incisive and cutting, and more... image seeking. Woolf sought to set out and make a case for, at least for the most part, a practical set of conditions for success. Duras is seeking only to describe them- and they are almost exclusively mental conditions (given some material help from certain external aids) created by the writer herself.

Then the thing takes a roundabout left turn brought on by a free association somewhere in her descriptions of the village near her house and suddenly we are talking more and more about death. Writing as death, death as bringing on and inspiring writing, death's impact on her "solitude", it's impact on her memories and the formation of her psyche- especially the lingering impact of the Second World War. And we end, Before Sunset-like, wandering through ruined Rome and discussing death and life and writing and unspoken longing until we wander right off the page.

I struggled to interpret this one. My historian's brain kept placing this in the context of its publication- 1993 brought about a resurgence of interest in WWII (the Maastricht Treaty process had dragged up a lot of old, unseasonable memories, Mitterand's checkered past with Vichy was about to come to light, the last Nazis were being rounded up and put on trial, WWI vets were scarce and WWII vets had begun to die in larger numbers, and there was a high-profile suicide on the socialist Left). Is that what all this rage against the Germans and the heavy-handed description of the death of the fly - seriously, it went on for several pages- was about? I understand it as an exploration of the writer's observational instinct, but I think that that was a secondary concern in Duras' thoughts at best.

Or was she genuinely just another dying relic of a bygone age- France was full of them at this time- for whom the past was nearer than the seemingly surreal, unsatisfying present? It makes sense. There's a big element of the public discussion in France that's still that way.(There's a lament for '68 in here, too.)

That might explain why her writing felt somewhat dated as well- for example the existentialist/minimalist toned final chapter in Rome. It felt like a frozen, boiled down shadow of Hiroshima, Mon Amour. Someone more well versed than me would have to tell me whether Duras always wrote like this- that is if her writing had not changed significantly since the war, or whether this is a throwback.

It all made for a rather aimless, anachronistic, occasionally preachy experience. I can see how this fits into the fabric of its time, but I'm outside the cultural memories that might make this particular sort of melodrama work for me.

However, I should highlight some individually lovely lines. This is still Duras. These are the reason to read:

"There should be a writing of non-writing. Someday it will come. A brief writing, without grammar, a writing of the words alone. Words without supporting grammar. Lost. Written, there. And immediately left behind."

"The inside of the church is truly admirable. One can recognize everything. The flowers are flowers, the plants, the colors, the altars, the embroideries, the tapestries. It's admirable. Like a temporarily abandoned room awaiting lovers who haven't arrived yet because of bad weather."

"A solitary house doesn't simply exist. It needs time around it, people, histories, "turning points," things like marriage or the death of that fly, death, banal death the death of one and the many at the same time; planetary, proletarian death. The kind that comes with war, those mountains of war on Earth."

"Before me, no one had written in this house. I asked the mayor, my neighbors, the shopkeepers. No. Never. I often phoned Versailles to try to find out the names of the people who had lived in this house. In the list of the inhabitants' last names and their first names and their professions, there were never any writers. Now, all those names could have been the names of writers. But no. Around here there were only family farms. What I found buried in the ground were German garbage pits. The house had been in fact occupied by German officers. Their garbage pits were holes. There were a lot of oyster shells, empty tins of expensive foodstuffs... And much broken china. We threw all of it out. Except the debris of china, without a doubt Sevres porcelain: the designs were intact. And the blue was the innocent blue in the eyes of certain of our children."

And finally:

"There is a madness of writing that is in oneself, an insanity of writing, but that alone doesn't make one insane. On the contrary. Writing is the unknown. Before writing one knows nothing of what one is about to write. And in total lucidity.

It's the unknown in oneself, one's head, one's body. Writing is not even a reflection, but a kind of faculty one has, that exists to one side of oneself, parallel to oneself, another person who appears and comes forward, invisible, gifted with thought and anger, and who sometimes through his own actions, risks losing his life." -

No leer

No quiero googlear para comprobarlo, quiero quedarme con la sensación de tener razón: la publicación de este libro es cosa de herederos y editores. La Duras no creo que haya pensado que estos textos podían formar un volumen. Tengo un par de reglas en mi vida: no ver partidos amistosos de ningún deporte (porque son una pérdida de tiempo para todos) y no consumir ninguna obra póstuma (porque por algo el artista decidió no sacarla a la luz).

Este libro empieza con algunas reflexiones de la autora sobre el hecho de escribir, que, digamos, zafa y después unos textitos que no sé si son incomprensibles o yo no les puse mayor atención porque no me importaban nada. El único que me sacó del sopor es uno que defiende a Stalin como el verdadero responsable de acabar con los nazis.

En fin, les diría que no pierdan dinero en este libro. Tampoco su tiempo, aunque debó admitir que se lee rápido porque, uno de los trucos de los editores, es publicar libros con letra grande y muchos espacios en blanco.

==

Si te gustan mis reseñas tal vez también te guste mi newsletter sobre libros que se llama "No se puede leer todo". Se pueden suscribir gratis, poniendo su mail en este link:

eepurl.com/hbwz7v La encuentran en Twitter como @Nosepuedeleert1, en Instagram como @Nosepuedeleertodo y en Facebook.

Gracias, te espero -

گمانم بعد از این دوراس را بیشتر با این کتاب بشناسم؛ پنج جستار که اغلبشان را دوست داشتم_ حالا انگار نوشتن و مکثهایش در من مانده

-

I'm not exaggerating when I say that this book is my Bible. I think every writer should read it, especially if you are someone who writes in a more literary style or in an experimental and unconventional style. I also recommend "Letters to a Young Poet" by Rainer Maria Rilke. Both of these books have been essential to my own awakening and evolution as a writer.

-

الترجمة جعلتني ألقي بالكتاب بعيداً

-

I borrowed this from the library expecting it to be entirely about a single subject: writing. It isn't. There are five chapters; each chapter is a stand-alone story.

The first chapter titled "Writing" is by far my favorite. It's beautiful and calming. It discusses the process of writing and its intimate connection with solitude.

Writers crave solitude, yet "there is something suicidal in a writer's solitude."

* * *

The second chapter is about a young British pilot who tragically dies at the age of 20, on the day WWII "officially" ends.

This chapter has the worst writing in the whole book. Whereas the first chapter deserves five stars, this barely scrapes up one star.

Why? One idea (the horror of a "child of 20" killed at war) is rehashed repeatedly for about 22 (!!!) pages.

* * *

The third chapter is a conversation that occurs in a hotel lobby between a man and woman. They discuss the love story of the Queen of Samaria.

It's a bizarre chapter/story; it reads like a warped mini-play.

* * *

The fourth chapter is a quick (possibly too quick) essay on "purity." Duras claims purity is a sacred concept in every culture.

+ Purity is an obsession in Christianity.

+ The insane preoccupation with purity led to the murder of millions of Jews in WWII.

+ Clearly, purity is ridiculous and others ought to be aware of the insidiousness of this seemingly innocent notion.

* * *

The fifth and final chapter is about an artist who is setting up his painting exhibition. He is a nervous man with frenetic energy; classic lovable weirdo.

This short story is odd, but I quite liked it.

* * *

In Summation:

The first chapter took my breath away; the final chapter intrigued me. The second and third chapters I could've done without. The fourth chapter interested me, but didn't have as much depth as I would've liked.

Three stars. -

This collection includes five short pieces, of which I was most interested in Writing. In fact, I initially thought that the whole book was about writing, so that was slightly disappointing, albeit my own fault. What was more seriously disappointing was the collection itself, which really wasn't as interesting or as good as I had expected it to be. Only Writing was worth reading, if I'm honest, and even that only had its moments, with an occasional passage that stood out. Perhaps if I had previously read Duras I would have been more interested or more lenient—as it stands, on its own, the collection left me unmoved and, too often, impatient with the generalities and annoyed at the inconsistencies. An example of one of the more stand-out moments:

"If one had any idea what one were to write, before doing it, before writing, one would never write. It wouldn't be worth it." (44)

You read it and you nod along, considering it quite profound. But then you think, wait a minute? Aren't there ideas—stories—in the minds of writers that they think need to be told, and that they therefore go on to write? Isn't this just as true, if not truer, than what Duras just wrote? Surely, an entire book doesn't come ready-made, but some of the greatest works have materialized precisely because their writers felt that an idea needed to be shared, that a story had to be told. As if Steinbeck did not have East of Eden in mind! Of course, this is Duras's personal account of writing. But while unconventionality is nice, it needs to be grounded in something substantial in order to become meaningful. That is, to become more than mere eccentricity, which doesn't last. -

"Algunos escritores están asustados. Tienen miedo de escribir. Lo que ha ocurrido en mi caso, quizás haya sido que nunca he tenido miedo de ese miedo. He hecho libros incomprensibles y han sido leídos".

Pues este fragmento define para mí este libro de relatos de Marguerite Duras. Muchas frases subrayadas en el primer relato o como quiera llamársele (el llamado "Escribir"), que como casi siempre están hilados con la marca de la casa de la autora, es decir, como le da la gana.

El relato "Roma" ha sido un auténtico enigma para mí. Pero a pesar de ello, la leo, porque es muy Duras.

Yo encantada de leerla siempre. Si es un regalo que te llega de manos de una amiga, más. -

ilk deneme (yazmak) çok iyi, sonrası kötü.

-

كتاب في مديح الوحدة. أكثر منه في مديح الكتابة. جاءت دوراس لتقدم لنا كتاب عن الكتابة، فوجدت نفسها تقدم لنا كتاب عن الوحدة. كأنك، لتكتب، يجب أن تكون وحيدا، منعزلا. ومع ذلك، لن تكون وحيدا أبدا، هذا ما تقر به دوراس، التي عرفت الوحدة في منزلها الذي عاشت به في نوفل شاتو، لمدة عشر سنوات. تقول بأننا لن نكون وحدنا أبدا. لا نكون وحيدين فيزيقيا أبدا. في أي مكان. نسمع الأصوات في المطبخ، من التلفزيون، في الشقق المجاورة،... ثم تحكي، عن رؤيتها، لذبابة تموت. بقيت تراقبها لثمان دقائق تقريبا، كأنها تقول، ومعنا الموت أيضا، لن نتخلص منه.

أحب كتابة دوراس: موجزة، مكثفة، متشظية، كتابة فريدة. تخص دوراس وحدها. لا تشبه سوى نفسها.. -

Cinco textos, entre ensaios e contos.

Escrever – 5*

A morte do jovem aviador inglês – 4*

Roma – 4*

O número puro – 3*

A exposição da pintura – 2*

Gostei sobretudo do primeiro texto, que aborda a necessidade da solidão para escrever, da maneira muito crua da autora. Também são abordados outros temas, como a morte, a guerra, a paixão, a criação artística.

"A morte de uma mosca é a morte. É a morte em marcha em direção a um certo fim do mundo, que alarga o campo do último sono. Vemos morrer um cão, vemos morrer um cavalo e dizemos qualquer coisa, por exemplo, coitado do bicho... Mas se uma mosca morre... não dizemos nada, não tomamos nota, nada." (p. 42) -

واضح أن الكتاب جميل، يمكنك أن تحس بذلك. الترجمة -للأسف- لم تكن بالمستوى المطلوب. لقد كانت تتمزق بصورة مزعجة.

-

hiç sevmedim yahu. duras ile başka bir kitabını okuyarak tekrar bir araya gelmemiz şart. çok üzülüyorum böyle ilk tanışmalara.

-

Not the best place to start with Duras, but if you're familiar with her writing this is a cache of jewels. The last piece (of five) was the only one that didn't leave an impression on me, but it's so short that it hardly matters.

-

My first proper book to have completed in French!! Have tried multiple times but has been to tough /haven’t chosen the right stuff. This was short so was more manageable and also had no passé simple which I’ve only recently been learning. Hoping to incorporate more French into my reading cos I got a loooot of vocab to learn.

-

لا أدري ماذا أقول عنه ، من يقرأ العنوان يظن أن الكتاب يتحدث عن الكتابة ، و من يقرأ المضمون يكتشف أن الكتاب يتحدث عن الوحدة ، فقد تحدثت عن الوحدة و عن بيتها في نوفل شاتو اكثر مما تحدثت عن الكتابة .

-

Duras dice que la soledad del escritor no se encuentra, que ese tipo de soledad se hace y que ella —como no podía ser de otra manera— construyó la propia.

En «Escribir» también habla de su casa, de su obra literaria, de su filmografía, de sus amistades y amores. En este ensayo no hay nada convencional (¿cuándo sí en su obra?). Cada vez que amenaza con llegar al corazón del libro, entregar una respuesta sobre el acto de escribir. Marguerite huye. Nunca hay claridad en las respuestas, toda la luz se concentra entre los signos de pregunta. Ella lo sabe, por eso cuestiona. -

Ba, hay bốn ngày + đêm, nhất định chẳng làm gì, chẳng làm gì chỉ để nhất định không làm gì cả, để trốn việc, để không nghĩ tới các deadlines, để được chìm đắm một mình một cõi, và quyết định chỉ đọc và đọc lại M.Duras, sau một cuộc nói chuyện dài thật dài về bà. Tất cả những cuốn sách mình có được lôi ra, xếp cạnh đầu giường, và cơ hồ có lúc mình không biết là mình đang đọc, đọc chỉ để đọc, để đọc lại, để đọc hết, để không phải đọc nữa: Đập ngắn Thái Bình Dương, Viết, Tình, Người tình, Người tình Hoa Bắc, Nỗi đau, Hiroshima Tình yêu của tôi, Nỗi đam mê của Lol. Stein. Hình như còn thiếu cái gì đó đã được dịch, Mắt xanh tóc đen, hay gì đó.

M.Duras từng là một sự say đắm nhẹ khi mình 19, và là nỗi chán ngán khi mình đã...già ở tuổi 21. Giờ còn già hơn nữa, nên đọc và đọc lại Duras, chỉ để kết thúc việc nghĩ về bà, đôi khi, trong các câu chuyện tình yêu nhảm nhí của đời thường. :P

Nỗi đau và Hiroshima vẫn là hai cuốn sách mình yêu thích hơn cả trong số này, đọc lại vẫn xúc động. Và Đập ngăn Thái Bình Dương nữa, nỗi mệt mỏi khủng khiếp của mùa khí nóng, của xứ nhiệt đới, nỗi khát mưa. Viết là một cuốn sách ổn, nhưng Tình, thì không sao vào nổi.

Những điều vẫn ở đó, đam mê, tình yêu, những cuộc tình, những hiện hữu không tên gọi, cái gì bên dưới, bên trên, ở giữa và đằng sau tình dục, thân xác, hơi nóng, mưa, hiroshima, nỗi đau, cơn đợi chờ, ham muốn, thiếu hụt, sự thẳng băng thản nhiên... Nhưng những điều vẫn ở đó đã không còn ở đó nữa.

Bạn nói: Phải đọc Summer Rain cơ, mới thật là weird, mới thật lạ lùng. Hay là lại đọc? -

If I could give it zero stars, I would. this is some of the most pointless, incoherent stuff I've ever read. to boot, it's not interesting, so it's just a tumble of words. If this is indeed the way she thinks/thought, I'm exasperated.

She keeps going over her topics in circles, repeating things over and over.

And no, I really don't think I'm being too harsh. this woman is a hypocrite and a mysogonistic feminist. How can one be a mysogonistic feminist? By thinking "women are useless, but not me, I'm a special woman, and I deserve special treatment". that is Marguerite Duras.

to put it mildly, I find it hard to get through her words without splitting my head in two with all the eye-rolling. -

الكتاب عظيم جدا، امرأة تكتب عن فعل الكتابة. والسيء به كانت الترجمة بلا شك، ابتداء من عدد الصحفات حيث تبلغ عدد صفحات الكتاب بنسخته الفرنسية 123 صفحة، فيما الترجمة الانجليزية كانت 144 صفحة ولكن الترجمة العربية أتت بـ 33 صفحة تسبقها 24 صفحة كمقدمة. ذكر المترجم أنه وخلال ترجمته كان يحا��ل الحفاظ على طريقة الكاتبة في كتابة جمل مختزلة ومكثفة، لكن ما وجدته أنه وخلال عدد من المقاطع أتت الترجمة ركيكة، وللأسف لم يذكر سبب الاختلاف الكبير في عدد الصفحات مقارنةً بالكتاب بلغته الأصل. كما أني أسعى لقراءة الكتابة بترجمته الانجليزية قريبا.

-

Beautiful, profound. I read this very very slowly. The pace and the tone were more akin to poetry than prose. There was a great sense of wisdom throughout - clearly Duras is a woman who thinks with great care and passion and continues employing those as she tries to write to express her findings and feelings to others. I wrote down lots of quotes.

-

The first chapter took my breath away. It was interesting to explore the author’s thoughts on writing but the rest - second, third, fourth and fifth- were mostly incoherent and somehow chaotic thoughts and dialogues..

-

La nada, bien escrita, (si la ha escrito Duras) ya es mucho más que nada.

-

«He necesitado veinte años para escribir lo que acabo de decir».

-

Jag tror det här är en bok jag kommer läsa om många gånger.

-

5 textes dont un seul dédié à l'écriture. Le texte sur l'écriture est vraiment une perle mais malheureusement j'ai moins apprécié les autres

"Écrire, c'est tenter de savoir ce qu'on écrirait si on écrivait — on ne le sait qu'après — avant, c'est la question la plus dangereuse que l'on puisse se poser. Mais c'est la plus courante aussi"

"Se trouver dans un trou, au fond d'un trou, dans une solitude quasi totale et découvrir que seule l'écriture vous sauvera."

"Etre seule avec le livre non encore écrit, c’est être encore dans le premier sommeil de l’humanité. C’est ça. C’est aussi être seule avec l’écriture encore en friche. C'est essayer de ne pas en mourir. C'est être seule dans un abri pendant la guerre. Mais sans prière, sans Dieu, sans aucune pensée sauf ce désir fou de tuer la Nation allemande jusqu'au dernier nazi"

"C'est un état pratique d'être perdu sans plus pouvoir écrire.. C'est là qu'on boit. Du moment qu'on est perdu et qu'on a donc plus rien à écrire, à perdre, on écrit. Tandis que le livre il est là et qu'il crie qu'il exige d'être terminé, on écrit."

"Ca rend sauvage l'écriture. On rejoint une sauvagerie d'avant la vie. Et on la reconnait toujours, c'est celle des forêts, celle ancienne comme le temps. Celle de la peur de tout, distincte et inséparable de la vie même. On est acharné. On ne peut pas écrire sans la force du corps. Il faut être plus fort que soi pour aborder l'écriture, il faut être plus fort que ce qu'on écrit. C'est une drôle de chose, oui. C'est pas seulement l'écriture, l'écrit, c'est les cris des bêtes la nuit, ceux de tous, ceux de vous et de moi, ceux des chiens. C'est la vulgarité massive, désespérante de la société"

"Je crois que c'est ça que je reproche aux livres, en général, c'est qu'ils ne sont pas libres. On le voit à travers l'écriture : ils sont fabriqués, ils sont organisés, réglementés, conformes on dirait. Une fonction de révision que l'écrivain a très souvent envers lui-même. L'écrivain, alors il devient son propre flic. J'entends par là la recherche de la bonne forme, c'est-à-dire de la forme la plus courante, la plus claire et la plus inoffensive. Il y a encore des générations mortes qui font des livres pudibonds. Même des jeunes : des livres "charmants", sans prolongement aucun, sans nuit. Sans silence. Autrement dit : sans véritable auteur. Des livres de jour, de passe-temps, de voyage. Mais pas des livres qui s'incrustent dans la pensée et qui disent le deuil noir de toute vie, le lieu commun de toute pensée"

"Dès que l’être humain est seul il bascule dans la déraison. Je le crois : je crois que la personne livrée à elle seule est déjà atteinte de folie parce que rien ne l’arrête dans le surgissement d’un délire personnel." -

Writing by Marguerite Duras seems to be about COVID-19 lockdown. It's about loneliness that can equate to madness, about storing food in a storage room during the war and about silence and the unnoticeable sounds that break the silent and break the absolute loneliness.

The book consists of five essays, each one of which focuses on a moment, an emotion, an action or a place that is important to the author. It is written in the typical Duras style with short and tangible sentences. There is lots of white space between the paragraphs and white space is what you really need during a lockdown to read everything paragraph by paragraph.

In the essay "Writing" Duras explores what it means to write, why she write, how she writes, where she wriites and when she writes. Loneliness and writing are intertwined. There is no writing without loneliness and silence. In the essay she also describes the death of a fly. The death of the fly becomes important because it is described and there is someone who had witnessed the death.

In the essay "The Death of the Young British Pilot" the death of the fly is contrasted to the British pilot's death. The pilot has perhaps been one of the last victims of WWII. He had died on the day WWII ended, while his plane crashed in the trees in Vauville, France. Nobody knows the exact time of his death but there is the grave and there is the old man who visits the grave every year and then he doesn't visit it the year after and ever again. The young pilot embodies the war and the ending of the war.

"Roma" consists of a dialogue between two people in a hotel in Rome. The conversation is about Rome, about its existence and importance.

"The Pure Number" consists of thoughts about purity as a word and as a concept. The book ends with "The Painting Exhibition", where another form of creativity is discussed. There is the artist and his paintings and how the paint transforms into a painting on its way from the palate to the canvas. The book starts with writing about writing and it ends with writing about painting.