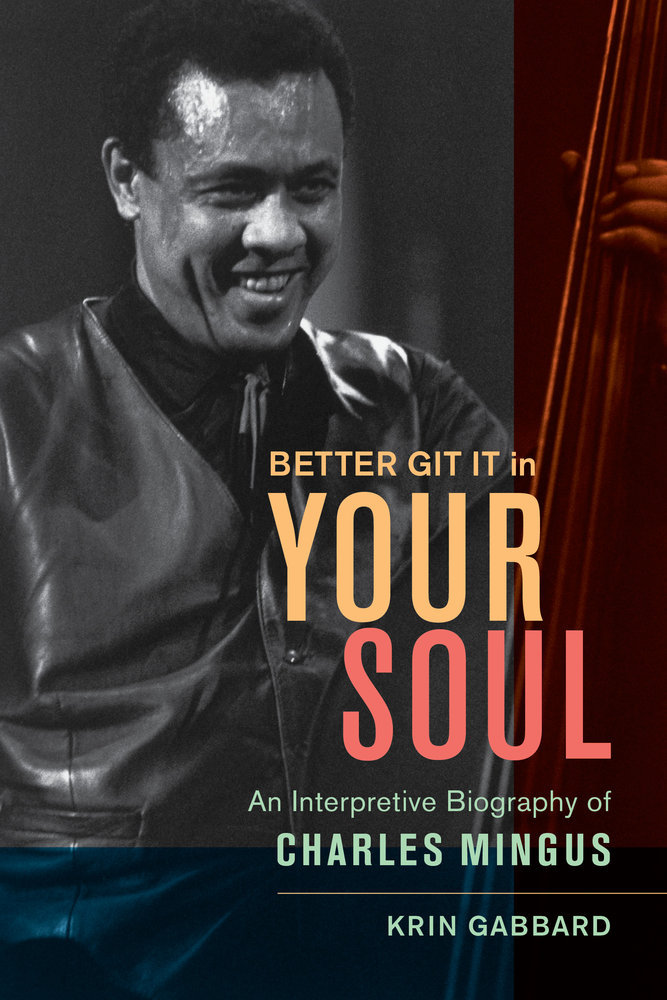

| Title | : | Better Git It in Your Soul: An Interpretive Biography of Charles Mingus |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 0520260376 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9780520260375 |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 336 |

| Publication | : | First published February 1, 2016 |

Better Git It in Your Soul: An Interpretive Biography of Charles Mingus Reviews

-

I just wanted to say up front how much I like the fact that Krin Gabbard published this book after retiring from SUNY Stonybrook.

This is not your typical musician’s biography. I’m actually not much of a fan of musicians' biographies, because too often they are too uncritically full of praise and idol worship. Too often, they are poorly written or the subject’s life isn’t dramatic enough to make the writing interesting or the biographer doesn’t know how to take the material of the musician’s life and make it interesting. Sometimes, the chronological approach that dominates the organization of biographies just seems plodding and restricts the biographer’s imagination and insights. The recent biography of Bill Frisell by Philip Watson, "Bill Frisell, Beautiful Dreamer: The Guitarist Who Changed the Sound of American Music" (2022) is thoughtful but runs out of gas, because, I think, the chronological approach is not the best way to make sense of Frisell’s still unfinished career. I much prefer a book like Graham Lock’s exploration of Anthony Braxton, "Forces in Motion: Anthony Braxton and the Meta-reality of Creative Music" (1987), which grounds itself as a documentary of the Braxton Quartet tour of Britain in 1985, but Lock also brings a variety of discursive lenses and varies the organization of the book to make it an interesting read.

All that said, Krin Gabbard produces a biography that is not dependent on chronology and moves between different discourses (musical, cultural, historical, literary, film studies). It helps that Charles Mingus was a dynamic, controversial and mercurial character throughout his life and to whom others reacted, positively or negatively, in words and/or actions. It also helps that Mingus was a prolific musical genius who produced lots of music worth talking about.

Gabbard’s organization is recursive. He comes at Mingus and back at Mingus in a variety of ways. In the style of the 33 ⅓ volumes, Gabbard begins with his own discovery and love of Mingus. There are a few details of Mingus’s life and music in this section, but not too many. This section allows Gabbard to do some “Mingus changed my life” idol worship, which he contains here without letting it spill over into the rest of the book too much. In the second, he develops a well-researched chronological discussion of Mingus’s life, looking some at the music but more at the social forces (family, geography, art and culture, education, relationships, sex, history, racism, and class) that helped shape him or, better still, the social forces to which Mingus’s strong personality reacted. Resonant with this biographical chapter is Mingus’s own autobiography, "Beneath the Underdog" (1971), but Gabbard sticks to what he can know through research and distances himself from Mingus’s autobiographical flights of fancy and fictionalizations.

In the third section, Gabbard looks at Mingus as writer, focusing on his poetry as well as "Beneath the Underdog" as both autobiography and literary artifact. He also positions Mingus within the Beats, his importance for them and their importance for him; in particular, he focuses on comparisons to Bob Kaufman and Ted Joans. As scholar, Gabbard does a lot of contextualizing here, introducing other jazz (auto)biographies as well as discussing the Beats. I only wish that Gabbard had done more close reading work with Mingus’s poetry and autobiography. At the end of the chapter, I don’t feel that I understand Mingus’s works as well as I do the contexts. In the film, "Moonage Daydream," David Bowie speaks of the importance of Kerouac and the Beats, but the film does not then pursue a close analysis of how Kerouac and the Beats influenced his music: it’s a movie, makes its points, gives the viewer the opportunity to think about those connections, and then moves on. A book can spend more time working up a literary analysis, but Gabbard doesn’t, at least not enough of one.

In the fourth and fifth sections, Gabbard turns fully to the music. This is my favorite part of the book, because Gabbard is meticulous and thorough, and he uses his extensive research well to write a music history or musical biography of Mingus. I learned a lot about Mingus’s evolution, from the straight ahead jazz (Armstrong, Ellington) of his early career through the different bops, third stream, his resistance to and then adaptation (kind of) to free jazz by the end of his life. His dedication to Ellington remains consistent throughout his life, no matter the style of jazz. There is always something Ellingtonian about Mingus’s music. Mingus’s genius, his mercurial temper, civil rights politics, his “hot” reaction to racism, his love of the western classical tradition, his attempts to run an independent music label and be free of the white-owned music business, and his contentious relationship with almost everyone and the categories that would box him in: these are the factors that produced so much amazing music. The fifth chapter is really interesting, because Gabbard looks closely at three musicians–Dannie Richmond, Eric Dolphy, and Jimmy Knepper–their relationship with Mingus and their impact on his music as well as his impact on them. What Gabbard shows is that Mingus’s music was not the result of a solitary person working alone but of intense interpersonal and collective engagement. Exploring how this creative process works with three particular musicians is fascinating.

Finally, the epilogue in on Mingus and the movies. It’s kind of a throw away chapter, because it doesn’t offer any more insights into Mingus and his music. Film is one of Gabbard’s specializations, so I understand why the chapter is in the book. If the purpose of the chapter is to show Mingus’s broader cultural impact, Gabbard needed to do more than look at movies.

I like the book. It has its weaknesses, but its strengths are many, and it is leading me to listen to more Mingus, albums that I was unaware of: so many of those. -

Gabbard first hear jazz late at night on a transistor radio hidden from his parents after lights out. Developing a taste for jazz, he became fascinated with Mingus, but was only able to see him once before the musician died in 1979. Now, working with interviews with virtually everyone who worked with Mingus, the newly available papers surrounding the publication of his semi-autobiographical memoir (lots of names were changed, and stories with a grain of truth were magnified in some telling ways), and the music itself, Gabbard offers an impressionistic biography that places Mingus in the context of his times and the jazz world.

-

An interesting but flawed survey of the life and work of Charles Mingus. Gabbard separates his material into roughly four themes—life events, analysis of Mingus's prose work, Mingus and jazz history, and an exploration of three of his collaborations—with a coda, of sorts, concerning Mignus's music in film. While Gabbard spends a lot of time with the typescript of the semi-autobiographical

Beneath the Underdog (the published work sounds unpleasant enough, so the pre-edited draft must have been frightful), elsewhere he doesn't add much new interview material, and his reliance on Wikipedia for a few citations is just lazy.

Nevertheless, the creative talents of Mingus, with so much energy (Gabbard speculates about bipolar disorder) that he could not be creatively pigeonholed, and who shared a bandstand or recording date with practically everyone in mid-century jazz, shine through the book. -

Krin Gabbard, AB'70

Author

From the author: "After exploring the most important events in Charles Mingus’s life, Krin Gabbard takes a careful look at Mingus as a writer as well as a composer and musician. He digs into how and why Mingus chose to do so much self-analysis and how he worked to craft his racial identity in a world that saw him simply as 'black.' Gabbard sets aside the myth-making to argue that Mingus created a unique language of emotions—and not just in music." -

FTC Disclosure: I received this book free from Goodreads hoping I would review it.