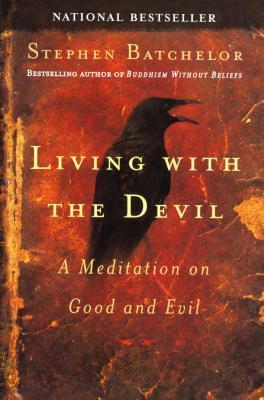

| Title | : | Living with the Devil: A Meditation on Good and Evil |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1594480877 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781594480874 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Paperback |

| Number of Pages | : | 240 |

| Publication | : | First published January 1, 2004 |

In the national bestseller Living with the Devil , Batchelor traces the trajectory from the words of the Buddha and Christ, through the writings of Shantideva, Milton, and Pascal, to the poetry of Baudelaire, the fiction of Kafka, and the findings of modern physics and evolutionary biology to examine who we really are, and to rest in the uncertainty that we may never know. Like his previous bestseller, Buddhism without Beliefs , Living with the Devil is also an introduction to Buddhism that encourages readers to nourish their "buddha nature" and make peace with the devils that haunt human life. He tells a poetic and provocative tale about living with life's contradictions that will challenge you to live your life as an existence imbued with purpose, freedom, and compassion—rather than habitual self-interest and fear.

Living with the Devil: A Meditation on Good and Evil Reviews

-

Have you ever wondered about the randomness inherent in even the most trivial events? For example, how often have you been about to lock the front door of your residence and go out to your car, when you suddenly remember that you left your phone on the kitchen counter? Or your wallet on your dresser? Or your notes for that important meeting later today on your desk?

In those few seconds that it takes you to re-enter your home, retrieve the forgotten item, and then finally lock the door and walk to your car, you have inadvertently altered the entire flow of events that will ensue when you drive away. You will enter the flow of traffic three or four minutes after the time you would have entered it had you not been delayed in leaving, so there will be an entirely different array of drivers in front of, behind, and alongside of you on the road. The entire pattern of cars passing each other, navigating into and out of lanes, stopping suddenly for a red light or accelerating to make it through a yellow light, will be different because your place in the flow is different. An accident that might have occurred, had you entered the flow earlier, now will not - and you will never know. Or one that would not have occurred now may occur.

And you are not the only random variable in this traffic scenario - every other driver around you is also where he or she is at that precise moment thanks to his or her own random patterns of behavior prior to entering their car.

If the above reflection has you musing for a minute or two about the role contingency plays in even the most inconsequential events, then reading Stephen Batchelor's "Living with the Devil" will have you pondering for days about the inescapable impact of contingency upon the most significant aspects of our lives.

Subtitled "A Meditation on Good and Evil", it could just as appropriately have been called a meditation on contingency, the essence of which Batchelor neatly captures with the phrase "this need not have happened". While we typically think of contingency as the causes and conditions which give rise to a particular event, rendering that event dependent upon those causes and conditions for its occurrence, Batchelor forces us to recognize that contingency is not only the causal principle underlying everything that happens, but also the phenomenological truth that anything that does happen might just as easily not have happened.

In my traffic scenario above, the contingent array of participants in the flow of traffic at any given moment not only determines if an accident will occur, but also if one will not occur. Batchelor takes this idea much further, arguing that once we truly grasp the meaning of contingency, we must conclude that each and every one of us "need not have happened" - our very existence is grounded in the same contingency that governs the cosmos. His insightful commentary in this regard gives the reader a new way of grappling with the ever-challenging Buddhist concept of "no-self".

You might think that the title "Living with the Devil" refers to living with this rather uncomfortable notion of our own contingent nature. But in fact, Batchelor considers "the devil" - or, in the Buddhist tradition, "Mara" - the seductive allure of doctrines, whether religious or secular, that offer the false consolation of an explanation of the meaning of our lives and an assertion of our central place in the larger scheme of the universe. Our task, he argues, is to resist such temptation, and give ourselves over to the ceaseless uncertainties of contingency.

In a brilliant chapter entitled "Learning to Wait", Batchelor shows us how an understanding of contingency can illuminate our meditation practice. Here are a few excerpts: "The release of nirvana rests in a serene astonishment at a fleeting self and world." "You just wait in the abyss of perplexity without expecting anything." "One waits at ease for a response one cannot foresee and that might never come." "The practice of waiting is to learn how to rest in the nirvanic ease of contingent things."

As is always the case, Batchelor's writing in this book is impassioned, persuasive, and intensely personal. The reader learns from him, and learns about him. He reveals himself in these pages as a prodigious scholar, a gifted synthesizer of literature and philosophy, and a contingent human being with the same cravings and aversions as the rest of us.

One could want little else from an author, and nothing more from a book. "Living with the Devil" is an invaluable reading experience for all of us contingent beings, Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. -

This book sits in a nice place between the latest "Buddhism for Beginners"-esque books and the heavier, more historical Buddhist religious texts. Which is great, as this was what I was looking for.

Books that are aimed at those completely new to the subject often repeat definitions and concepts I already know, and those that are aimed at practitioners are often too esoteric for me, as if I'm missing a few graduate classes to fill the gap. I feel like I have a halfway grasp of the basic tenets now and am mostly interested in the more secondary issues of how the tenets of religions inform our ways of looking at and reacting to the world. Unfortunately, I've had a hard time finding books that are aimed my way: at someone who is not a beginner, but who also isn't interested in going straight to the source of the religion.

This book, on the other hand, dives into one of the niches that lends itself well to that sort of secondary analysis. In doing so it hits on topics that touched a chord in me, making me feel like it was not just a thought experiment, but an actually helpful book about how to deal with real life and real people. The author's viewpoint on the nature of evil (mara) and good and suffering, too, was fresh and felt like he was really bringing new thoughts to the table, rather than just repeating what I'd already heard. Even when, especially in the third section, he starts drawing on historical information, it's in a useful way, to provide examples of particular ideas.

Overall, I left a lot of dog-eared pages in this book, and it was great food for thought. -

When we begin the journey along the Path that is opened to us by the Buddha's teaching, it seems that for many there is a period of heady realization and a sense of having found the Way. While that may be a fact, the predisposition of most is that the "self" moves in and takes it over and turns it into "my way". A trap for young players! Tthen seems to follow a period when "I" set about getting it perfectly right. In that there develops a struggle, however, with time and patience and simply coming back to bare awareness this will fall away into the space whereby one gains a sense of the openness and ease (though not lack of difficulty) of living the Path.

It is during this period that the issues of bringing the practice down from the clouds of spiritual idealism into the nitty gritty of everyday life arise with some forcefulness. Time to abandon the raft that brought us from the shore of ignorance to the shore of awareness. It will no longer be needed because the mind will never be able to go back the without awareness that it is happening and our experience and perceptions of self and life from that blinkered perspective will always ring hollow and the Path will call again.

It is here that we are all confronted with the very essence of our own nature and the nature of all things all conditioned phenomena. The truth that the search for the perfect place or state, the heavenly sanctuary where we can finally rest henceforth undisturbed is a destructive delusion. It is the very denial of that which we see as "bad" (the Devil, Mara) in our lives; the drive to banish the Dark Side that is the crux of our struggle and the source of all our suffering. This battle we all seem determined to engage in is seen in symbolic terms in all humanity's myths and religions. It is a recognition of the state of all phenomena as it is reflected within our own beings hence the importance of those myths and religions to the human psyche.

This book explores the manifestations of the Dark side, both personal and societal and looks at the whole process of active inclusion of the Dark side as a part of the whole. This is the surrender of the dualism that is formed as part of our natural thinking process, the surrender in fact of self. The fluid movement of each of us, no more than an energy, through the swirling contingencies that make up existence demand this inclusion and this surrender, for it is the negative that gives rise to the positive, the bad to the good, the dark to the light, hell to heaven.

The message here is that this is not a struggle; that struggle only arises from imbuing the sense of "self" and all its wants with a reality greater than the mere thought that it truly is, and hence without substance. With acceptance of our entire nature, all of who we are, we can with awareness choose in freedom our responses to what life brings and give up our reactions. The Path is the practice that brings that awareness into being and with it the possibility of Nirvana; not the airy fairy notion of a continuous heavenly blissful state but a state of equanimity in the face of all our tribulations. That state of equanimity like all things is impermanent and must be constantly recreated minute by minute through practice. Anyone can do it, the excuses we give always boil down to only one thing, our humanity, because what we see most in it is the devil, but the Buddha is within. Gautama found this and showed us that it was through his humanity that it was realised. He promised that we, like him could so realise our own Buddha nature, including the aspects of the devil within that give rise to that very same Buddha. -

i adore this book. it's buddhism for bookish anti-socialites. it's a constant reminder of where we're all at in a ridiculous universe. it's beauty, truth & now all at once. i reread it constantly. (in the interest of full disclosure i also constantly reread harry potter, madeleine l'engle & the bridge to terabithia)

-

Stephen Batchelor is the Buddhist author for the secular Buddhist! Highly recommended.

-

The arguments are derivative and, worse, lacking in nuance: eg. no distinction between contingent, groundless, temporal, beyond one's control, etc.

-

First class stuff from Mr Batchelor

Another finished read but one I'll return to. Another penetrating and intelligent work from a sane and rational voice of our time. A study on how polarised, crystallised thinking and ego driven reactivity towards "anything at all" outside of what we "want" to hear is blocking the personal growth path - but also the cause, in one way or another of tribalism, hatred, racism, nazism, misogyny and wars. We live in times where huge amounts of disinformation scares and polarises us further but there are ways to step out of the circle and see where we are embroiled in such things. All of Batchelor's works have intrigued and educated me on many levels and they've been particularly helpful during these (deliberately) confusing times. -

I enjoyed this book when I first read it ten years ago, and just this month, re-reading it with my sangha's book club, I found some chapters so good I could have underlined almost every line. The general thrust of Batchelor's argument in this book, is that rather than falling into the twin poles of externalizing and projecting "the demonic" onto others or suppressing it with denial, we need to learn how to live with it by recognizing and understanding those patterns of thinking and behavior that can so inhibit our flourishing.

But for me, the things that most resonate include Batchelor's relentless emphasis on the contingent nature of existence. All religious thinking -- including much of buddhism -- seeks to offer a solace in the face of contingency via positing some "transcendent" realm and the "hidden hand" of either god, karma or destiny that would seem to offer some underlying order and purpose to the random, contingency. As Batchelor writes: "...embracing contingency requires a willingness to accept the inexplicable and unpredictable instead of reaching for the anesthetic comfort of metaphysics." I read a sentence like that and feel it as a strong tonic antidote for all the new-agey bullshit of contemporary yoga and buddhism that offers some sop to the existential situation we find ourselves in.

Repeatedly he criticizes the tendency found in buddhist history to reify emptiness from pointing to the lack of any self-essence into some "subtle dimension of reality or a mystical state of mind" whereby it becomes "fetishized as another privileged religious object."

As a naturalist, I also find his treatment of consciousness also a bracing corrective to the distortions so common among contemporary western buddhists who elevate consciousness into some subtle atman more akin to Vedanta than what early buddhism and contemporary neural science seem to point to. "To be conscious is to be conscious of something," he writes, dismissing the whole notion of some idealized, independent "pure consciousness." Batchelor is correct when he writes: " Buddha regarded consciousness as contingent not only on sensations, feelings, perceptions, concepts, and choices but also on illusions and conditioned behavior. The human organism is instinctively prone to reify the experiencing "I" as a separate conscious entity and to behave as though the world were a domain for gratifying its desires.... For him, the problem with consciousness was the way it appears to be the irreducible core of oneself.... This innate sense of being apart from the flux of life was, for Buddha, one of the root causes of human isolation, alienation, and anguish."

A few years ago, I was at one of the "Toward A Science of Consciousness" conferences held here in Tucson every two years when Susan Blackmore (who practices buddhist meditation) referred to "the illusion of consciousness." Deepak Chopra thought he was being clever when he called her out on "denying something so obviously existent as consciousness" which he -- following the idealism of Vedanta -- sees as primary ontologically. He literally scoffed at her. I managed to get to the mike and remind him (if he ever knew and clearly if he had previously known of this he shows a complete lack of understanding the radical implications) that the buddha saw consciousness, like everything else in the world, as no more stable or necessary (as opposed to contingent) than -- as Batchelor writes: "the flicker of a shadow or the bubbling of a brook." In particular, the passage I quoted is from The Phenapindupama Sutta where the buddha breaks down the five skandhas:

"Appearance is like a ball of foam; feeling like a water bubble;

perception is like a mirage; mental formations like a plantain tree;

and consciousness is like a magical display."

Many religious and spiritual paths valorize the light and attempt to suppress, destroy or deny the darkness. Batchelor shows how the shadow is intrinsically related to the light; the light of the buddha casts the shadow of Mara and Mara reflects the light of the Buddha back.

Or, as the Sandokai puts it:

Within light there is darkness, but do not try to understand that darkness;

Within darkness there is light, but do not look for that light.

Light and darkness are a pair, like the foot before

and the foot behind, in walking. Each thing has its own intrinsic value

and is related to everything else in function and position. -

I don't know any writer that updates and synthesizes Buddhism with the western tradition better. You could say that Sangharakshita created a movement along with his awesome corpus of books, and that's true, but in a certain way, even though he read deeply, maybe more than anyone I know, he was sort of a victorian. Batchelor has more modern assimilations of western literature, more philosophical than poetry, compared to Sangharakshita. They are both from England, and they are both self taught, and they both really dove into their traditions with fierce commitment. Batchelor says "The plight of both Mara and Satan is to be banished from life itself. My sense of alienation is like wise rooted in the numbness to interconnectivity. I feel as though I haunt the world rather than participate in it. Evan as I chatter to the midst of company, I feel eerily disengaged." I see Sangharakshita as having deeper, more committed friendships. When I met Batchelor, the most interesting thing in the encounter was that someone asked him who he saw his sangha was, and he said the editorial board of Tricycle. So he's a kind of star Buddhist who likes to hang out with other stars. Sangharakshita founded a movement that is world wide. His memoirs are filled with friendships. I compare the two because they are my two favorite writers, and they feel so different to me. I've always had parties with weird people who wouldn't necessarily like each other, but someone I find appreciation in very different people.

Someone asked me why I was reading the book. They were wondering if I was particularly into the question of good and evil. My response was that during hard times you go back to your sources. I find Batchelor's writings as one of my sources. -

This is a notable work of comparative religion and spirituality, which draws predominantly on Buddhist philosophy to examine the question of evil (through the metaphor of Mara/"the devil") in human life. I thought the book would follow the well-trod path of trying to explain how there can be bad in a world of good - à la Christian apologetics - but it actually approaches the problem by examining the evil in our own selves, recognizing that this is the more honest and accurate approach. Evil isn't some nameless, faceless force, but lies in potentiality in each of us.

Like in

Buddhism without Beliefs, Batchelor focuses on mindfulness as a technique to combat the devil(s) of our own making. As in the latter book, this is a really helpful tool, and it bears repeating. We too often forget that it's a goddamn miracle we're alive in the first place, and from this wondrous awareness of our own contingency we can derive compassion and fight off unneeded suffering.

Batchelor's humanist arguments may be heavily Buddhism-influenced, but he ultimately espouses living between traditions and taking wisdom from science, religion, and art to forge your own unencumbered path. As much as that can be a stereotype of modern, Western new-age types, it's still true. Life's too short to waste time on self-reinforcing dogmas. -

The subtitle of the book is 'a meditation on good and evil', and it feels like a meditation to read, rather than a systematic presentation - very refreshing and life-affirming, and timely for me, after wading through Mo Yan's meaty tome!

I really like reading Stephen Batchelor's work. I appreciate his multiple perspectives and his ability to weave useful insights out of the spaces between traditions.

I was particularly taken this time with the image of a path as an empty space, rather than a place where you put your feet - path as an astonishing verb, a movement, an unconsoling homelessness - path as an unimpeded gap between other things, an anarchic gap, fertile only insofar as it remains unsettling, unclaimed and unenclosed.

I was also rather challenged by the question about where compassion comes from. Just because we grow in our awareness, hear the cries of others, identify with others as one with us in the body of existence - why should we assume that this means we will care? The value of caring is not automatic, as is plainly evident in this world where none of us can claim to be uninformed. -

And by "devil," he means the metaphorical devils within each of us that lead us to desire things that we know are unhealthy, unsatisfying, or hurtful to others. While writing primarily from a Buddhist perspective, Batchelor draws on a number of other belief systems and cultural myths--from Christianity and Islam to Shakespeare and Baudelaire--to enrich his meditations on how humans come to grips with the essential tension of the human condition: our desire to be good, and the continual temptation toward sin.

-

This is a very interesting book that I didn't expect to enjoy.

The key concept he explores is this notion of the Mythic character Mara who was Buddha's metaphysical foe, always tempting him to deviate from his path, giving in to desires and their associated passions, fearing death, etc.

The book can be viewed as an explanation of how we can deal with "temptation" and the various psychological traps we can fall into that bring us unnecessary suffering and emotional pain. -

I really enjoyed much of the writing in this book. Some of his references to older poets and philosophers kind of went over my head, but there were some strong chapters with profound insight. I respect Stephen Batchelor and will almost certainly look into more of his writings.

-

One knows to care with compassion.

A good reminder to what where who and how, are just symbols.

This book fortified the intuition “about disconnecting with the establishment and conditions” one lives upon has being always with one. -

On hold for the unforeseeable future.

-

My experience reading this was precisely like what the title suggests. It's a very difficult book to read if your presumptions stand in your way, and once you recognize your presumptions the book becomes very easy to get through...

Well, that's not entirely true. If you've read Alone With Others or are familiar with Batchelor's... thing. then you may find some of the first chapters redundant (but then again, it's the kind of info that some people might need a refresher on). And much of the info in the first chapters is redundant with later chapters.

Altogether an open-minded book with a very practical and useful message about the importance of perspective vs. position and co-existence. This book benefited my life and helped me understand the values in relinquishing the need to be certain all the time and in admitting ignorance. Yeah, I am a better person because of this book... but maybe the editor could have made some more cuts.

I mesh well with Batchelor's "Buddhism Without Beliefs Model," and was pleasantly surprised to find this work very syncretic. He draws from Christianity and once even from Thurman.

If you're looking for a Batchelor book go for Alone With Others before this one, and if you feel like there are unanswered questions then I'd venture into Living With the Devil. -

Standing as an astounding survey of the most prominent schools of spiritual thought, 'Living with the Devil' proves itself a promising path to unframe and reform numerous, separate walks of belief into a harmonic, heuristic space of reference - it is here we may manage the many nefarious, compulsive tendencies of the human condition and redirect our focus from the falsehood of being 'necessary and permanent' to freedom found in being 'conditional and contingent.' Batchelor tenderly invites the reader's dogmatic minds into a profound, protogenic mutualism which, once read, sets a functional foundation for discussing the axioms which divide our many branching theologies, suggesting the trunk's break into many arms is the place we may reawaken to the truth of our inseparable unity.

-

Interesting look at Buddhist ideas through the lens of western religious ideas and mythology...also a comparison of evil in East vs west. I love this book because there is no “belief” that asserts itself or gets in the way...it’s funny that as an atheist, Steven Batchelor presents a very equanimous viewpoint as he doesn’t subscribe to any supernatural belief system, only the tenets of Buddhism. He even says that we can learn a lot from Judeo-Christian beliefs and mythology to enrich our understanding of Buddhist teaching. Fascinating read.

-

The first three-fourth of this book felt like word salad (existantialist + buddhist + christian thoughts and terminology mixed), which is maybe on me, but at the end Batchelor does what he's probably the best at. Interpret the buddhist canon from his very authentic and well argued viewpoint.