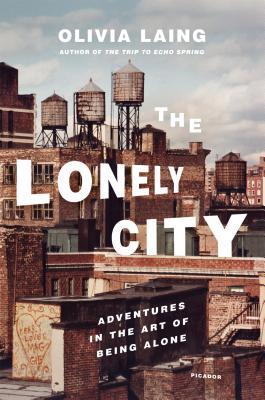

| Title | : | The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone |

| Author | : | |

| Rating | : | |

| ISBN | : | 1250039576 |

| ISBN-10 | : | 9781250039576 |

| Language | : | English |

| Format Type | : | Hardcover |

| Number of Pages | : | 336 |

| Publication | : | First published March 1, 2016 |

| Awards | : | National Book Critics Circle Award Criticism (2016), Goodreads Choice Award Nonfiction (2016) |

When Olivia Laing moved to New York City in her mid-thirties, she found herself inhabiting loneliness on a daily basis. Increasingly fascinated by this most shameful of experiences, she began to explore the lonely city by way of art. Moving fluidly between works and lives -- from Edward Hopper's Nighthawks to Andy Warhol's Time Capsules, from Henry Darger's hoarding to the depredations of the AIDS crisis -- Laing conducts an electric, dazzling investigation into what it means to be alone, illuminating not only the causes of loneliness but also how it might be resisted and redeemed.

The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone Reviews

-

It took me some time to read this simply because I found it riveting, beautifully written, and I wanted to savour it. Olivia Laing is a British writer and critic who moved to New York to be with her American partner only to find the relationship disintegrating. She falls prey to a crippling loneliness which gives rise to this hybrid memoir and art history on the theme of loneliness; and how she finds an alleviation of her loneliness through the visual arts. Given her family history, she focuses primarily on LGBT artists from New York's East Village with the exception of the odd Henry Darger from Chicago. She knits together a profound, moving and multilayered narrative. It covers her life, the work and lives of the artists, psychological insights and speculation, the state of being lonely specifically in a urban setting and a picture of New York through her eyes.

She looks primarily at four artists whom she is particularly drawn to. Edward Hopper whose work epitomises urban loneliness as exemplified through his most famous work Nighthawks, Andy Warhol whose life was spent hiding his sense of being apart through his entourages and equipment and the hoarded art of Henry Darger depicting the bizarre and the strange amidst a life of disintegration, violence and mental illness. Laing's particular favourite is David Wojnarowicz who experienced a particularly brutal childhood and life spent suffering as the eternal outsider. He was gay and contracted Aids. He channelled his rage at being stigmatised and silenced by a punitive rather than compassionate society by connecting with the group Act Up, to counter his loneliness until his death. His art and personal response is political to the cards life dealt him, he equates silence with death. His openness about his fear, pain, failure and grief has an honesty that allows him both to be vibrantly alive and counters loneliness.

The author looks at technology and its potent ability to connect whilst at the same time draws our attention to the solitary figure addicted to their phone and computer with its contradictory picture of the illusion of connection. There is the frustrations of social media, incessant social pressures, of people under constant surveillance and being judged rather than understood. The sense of loneliness is being compounded in our world today, with its shame and fear giving rise rise to concealment of the condition and carries heavy costs to public health.

Laing writes with empathy, humanity and curiosity pulling together disparate pieces of knowledge in her quest to understand and address loneliness. It raises as many questions as it answers. I did not always agree with the author but I did find the book intensely thought provoking and marvelled at its wide subject matter. I particularly engaged when near the end Laing says that amidst the shine 'of late capitalism, we are fed the notion that all difficult feelings - depression, anxiety, loneliness, rage - are simply a consequence of unsettled chemistry, a problem to be fixed, rather than a response to structural injustice..' She leaves us by saying 'Loneliness is personal, and it is also political. Loneliness is collective; it is a city'. Laing finds her own answers but prescribes no universal panacea whilst lauding the values of kindness and solidarity. A highly recommended book which I loved reading. Thanks to Canongate for an ARC. -

What does it feel like to be lonely? It feels like being hungry: like being hungry when everyone around you is readying for a feast.

As a person who spends a fair amount of time by himself, I was drawn to the subject matter of this book. I would say that I'm very comfortable in my own company but there are periods of isolation that I don't always enjoy. God I'm making myself sound like a total recluse here! To be clear I am blessed with lots of terrific friends but as an introvert I always need plenty of personal space. However I also live in a large city nowadays and to feel an emotional disconnect despite being among the presence of thousands is not uncommon.

In this thought-provoking study, Olivia Laing reflects on a period of intense loneliness which she endured in New York after a break-up. During this difficult time she turned to art for answers and explored the interpretations of urban isolation created by some notable and other lesser known artists . They saw themselves as outsiders amid the city's multitudes and channeled their piercing, heartaching loneliness into their work.

Some of her subjects I found more interesting than others - Edward Hopper and Andy Warhol's ideas on the theme particularly intrigued me. There is a lengthy examination of Hopper's seminal Nighthawks which revealed many new observations that I had not previously considered. The others I found less interesting - the chapters on David Wojnarowicz and Henry Darger didn't grab me as much. Maybe this is down to ignorance on my part as I am less aware of their work.

The book is part memoir, part art appreciation but I actually found Laing's findings and experiences of loneliness more compelling than the artists she describes. In fact I feel like the study would have been more complete if she fully opened up on her side of things. Her own thoughts on the seeming contradiction of isolation in a huge, bustling city intrigued me most of all and I wanted to know more about her personal situation. What really happened with the man who left her stranded in New York? How did she end up overcoming her exclusion from the world? What advice would she give to a person who finds themselves in the same predicament? Loneliness is never an easy thing to admit - society tends to attach a sense of shame and failure to the condition. I believe that Laing is holding back a little about her own experience, but I feel this book presents some valuable insights into the subject and the important role that art plays in understanding it. -

لا أعلم لماذا يعتقد الناس ان الجحيم هو مكان حار يحترق فيه كل شئ. هذا ليس جحيما. الجحيم هو أن تكون محاصرًا في عزلتك في كتلة من التلج. هذا ما مررت به.

-

“You can be lonely anywhere, but there is a particular flavor to the loneliness that comes from living in a city, surrounded by millions of people… mere physical proximity is not enough to dispel a sense of internal isolation… Cities can be lonely places, and in admitting this we see that loneliness doesn’t necessarily require physical solitude, but rather an absence or paucity of connection, closeness, kinship: an inability, for one reason or another, to find as much intimacy as is desired.”

This book was living a bit of a lonely existence itself. There it sat, on the bookshelf at the local library, amongst hundreds of other non-fiction books. No one had bothered to check it out during the past three years or more and was therefore doomed to the cruel fate of being axed from the catalog. (This, in my opinion, being a failure on the local community’s part to support a much needed library expansion. Who needs a new library when one can pour his or her money into athletic fields and school sports? Does anyone actually read anymore?! Ugh! But I digress!) In any case, this book, as well as a few others, weren’t necessarily saved from the ax but were given a nice new home by yours truly.

Gosh, this is another one of those books that came along at just the right time! For me, it was a perfect combination of a relevant topic (loneliness), fabulous setting (cities, particularly NYC), and art. Olivia Laing found that she was extremely lonely even in the hustle and bustle of a huge metropolis. Not surprising, really. But her attempt to relieve her feelings of aloneness was brilliant – she decided to study others who had lived their lives in isolation in one way or another. She began to research a number of artists, but her focus was mainly on the work produced by Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, Henry Darger and David Wojnarowicz.

“Not all of them were permanent inhabitants of loneliness, by any means, suggesting instead a diversity of positions and angles of attack. All, however, were hyper-alert to the gulfs between people, to how it can feel to be islanded amid a crowd.”

There’s a lot of narrative about the work these artists produced, as well as their background stories. I was more familiar with some (Hopper and Warhol) than with the others. But as is often the case, I found myself looking up images and adding other works of non-fiction to my list as a result. Interspersed throughout are also anecdotes about other artists, information learned by psychologists and other researchers, and stories about the author’s personal experiences in the city. She ventures into the territory of the internet and how that has affected our connectivity in a variety of ways, not necessarily always for the best. As I went along, I found myself nodding my head in agreement with a lot of what was shared. It’s not fun to talk about being lonely, particularly when one is surrounded by people nearly all the time. But there’s something about actually being seen, heard and understood that makes all the difference.

“What does it feel like to be lonely? It feels like being hungry: like being hungry when everyone around you is readying for a feast. It feels shameful and alarming, and over time these feelings radiate outwards, making the lonely person increasingly isolated, increasingly estranged. It hurts, in the way that feelings do, and it also has physical consequences that take place invisibly, inside the closed compartments of the body. It advances, is what I’m trying to say, cold as ice and clear as glass, enclosing and engulfing.”

I read this alongside a highly acclaimed novel I’d been anticipating for quite some time. Surprisingly, it was this book rather than The Handmaid’s Tale that I craved and reached for whenever I had a free moment! Go figure! While Atwood, one of my favorite writers, handled a topic near and dear to my heart as well, this is the one that truly latched onto me. It’s all in the writing, the timing and a whole lot of other personal variables sometimes, isn’t it?!! Highly recommended if you’ve ever felt lonely, love art, and yearn for New York City.

“Loneliness is personal, and it is also political. Loneliness is collective; it is a city. As to how to inhabit it, there are no rules and nor is there any need to feel shame, only to remember that the pursuit of individual happiness does not trump or excuse our obligations to each other. We are in this together, this accumulation of scars, this world of objects, this physical and temporary heaven that so often takes on the countenance of hell.” -

My full review, as well as my other thoughts on reading, can be found on

my blog.

Incisive but uneven, The Lonely City thoughtfully examines loneliness as it appears in the works of Hopper, Warhol, Wojnarowicz, and Darger. Laing mixes together biography, psychology, criticism, and cultural history, to consider how these men’s abusive upbringings and marginalized milieus informed their works’ complex representations of loneliness, connection, desire, and violence. Reminiscent of Rebecca Solnit’s work, Laing’s analysis is insightful, if a bit derivative of thinkers like Solnit and Sontag. As successful as these pieces are, though, the book feels aimless. Interspersed throughout the collection are bits of memoir—about Laing’s recent break-up, her experience of New York, her childhood identification with gay males. While interesting, the life writing comes across as disconnected from the rest of the book. The work, focused mostly on gay and avant-garde art/lit during the seventies and eighties, also erases the contributions of people of color to transgressive subcultures, reenacting the gentrification Laing rightly identifies as dehumanizing and alienating. -

إنه حديث العزلة حيث الأماكن غير المأهولة في روح الإنسان في سجنها الإنفرادي برغم حوم الجموع وإكتظاظ المدن.كتاب لا يمكنك أن لا تكمله إذا بدآت فيه ففي الأماكن المقفرة الخاوية أحياناً تصنع النفس معجزاتها وآمالها بعيداً عن الصخب واللجة

ما كتبته " أوليفيا لاينغ وترجمه محمد الضبع ونشرته دار كلمات يستحق الإهتمام ،فيه تتعرف عن هؤلاء المبدعين الذين عزلتهم الحياة فصنعت مجداً غير مبسوق لهم ،عرفتني أوليفيا عن أهم الرسامين في أمريكا وروت لي كيف كانت نمط حيواتهم المبهرة في صورتها المغلفة المقطوعة عن خيوط الوصال،طفولتهم،ميولهم ،جنسهم. ...الخ

من أبدع ما قرأت في سيرة لم يخض فيها علماء النفس في علمه بيد أنها ترجمت بلغة الأغاني والفنانيين العزل ومن استهواهم هوس الإنسلاخ عن العالم وضجيجه....لا بد أن يقرأ

ملاحظة: حسناً فعلت الكاتبة عندما أشارت إلى تعقب محرك البحث عند القراءة فهناك الكثير من المعلومات والر��ومات والمقطوعات الجديرة بالعلم ذكرتها من غير إطناب ولك عزيزي أن تتعقبها لزيادة المتعة والمعرفة -

Not a bad book, but not what I was looking for. I didn't realize to what extent the book would focus upon sexuality, AIDS and abused individuals. Even ordinary people, people with less serious problems than those studied in this book, are troubled by loneliness, lack of communication and meaningful contact with others.

The author wanted to get a handle on the loneliness she felt when her partner left her. She was in her mid-thirties and she felt utterly alone, alone in NYC. We are told that she was raised in a lesbian family, but we are not told the sex of her partner. While this is a memoir of sorts, it has in fact very little specific information about the author. You may ask what sex has to do with all of this. I mention sex only because in this book it plays a central role. Sex is a key component of the entire book. Another book on loneliness might focus more on age, on one’s ethnic background, on physical or psychological disabilities and less on sex.

The author looks at four artists: Edward Hopper (1882 - 1967), Andy Warhol (1928 – 1987), David Wojnarowicz (1954 – 1992) and Henry Darger (1892 – 1973). She states that the loneliness they felt affected their art. She does not make the claim that art can be seen as a means to remedying one’s feeling of loneliness, isolation or alienation. Why these four artists? Hopper because his paintings reflect a sense of separation between individuals. Take one glance at his painting Nighthawks and you see this. Here is a link:

https://www.google.fr/search?q=nighth.... Those he paints are not communicating with one another, there are no crowds and we observe through a window. Asked if his paintings are meant to express loneliness Hopper’s reply was ambiguous. Perhaps subconsciously, is the most we can get for an answer. The other three are LGBT artists, thus sharing common ground with the author’s own background. They all are from urban environments, NYC for three and Chicago for Darger. Their lives and their art forms are reviewed. All share problems relating to sexual, physical and/or mental disabilities and abuse. Yet regardless of the similarities that do exist, each one’s art is completely different from the others’. I don’t see any revolutionary conclusions that can be drawn from the study, except maybe one – that society must take an active role toward abolishing sexual discrimination and it must actively work toward helping the weak, the mentally disabled, the poor and those physically and sexually abused. It doesn’t say all that much about loneliness though, and that is what I thought was to be the central focus of the book! For me the book has a political message rather than a philosophical one.

The author queried how it could be possible to be lonely when living in an urban environment. This was for me self-evident. We all know that one can be alone in the middle of a crowd. Just because one has people around it doesn’t mean there is communication.

I cannot say I necessarily agree with all the ideas the author proposes on art, on loneliness or on social media. I grant that her ideas can be used as a starting point for further discussions.

I suppose the book might have engaged me more if I had loved the art of the artists described. Hopper’s I like but the others do little for me.

A word about the writing, the prose, the lines. If I say the writing is excellent, and it is, I don’t mean that it is lyrical. It is instead lucid, coherent, expressive and utterly clear.

The audiobook is narrated by Zara Ramm. Her reading is fluid. What is said flows into your head and you completely understand. You feel as though you are thinking the thoughts yourself, but the speed is so rapid you get exhausted and it is necessary to take breaks. You are left no time to think on your own. I prefer a slower speed. Let me point out that my view of the narration has not influenced my rating of the book.

Even if there are commonalities between the different artists, the book lacks cohesion. It is neither a memoir about the author, nor does it provide complete biographies on the four artists and I do not see how this book has helped the author resolve her own sense of loneliness. If it has, she has not explained how. It does make a political statement, mentioned above in the third paragraph. -

Whereas alcoholic writers were the points of reference for her previous book, the superb The Trip to Echo Spring (2013), here outsider artists take center stage: Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, David Wojnarowicz, Henry Darger, and the many lost to AIDS in the 1980s to 1990s. It’s a testament to Laing’s skill at interweaving biography, art criticism and memoir when I say that I knew next to nothing about any of these artists to start with and have little fondness for modern art but still found her book completely absorbing.

For several years in her mid-thirties, British author Olivia Laing lived in New York City. A relationship had recently fallen through and she was subletting an apartment from a friend. Whole days went by when she hardly left the flat, whiling away her time on social media and watching music videos on YouTube. Whenever she did go out, she felt cut off because of her accent and her unfamiliarity with American vernacular; she wished she could wear a Halloween mask all the time to achieve anonymity. How ironic, she thought, that in a city of millions she could be so utterly lonely.Loneliness feels like such a shameful experience, so counter to the lives we are supposed to lead, that it becomes increasingly inadmissible, a taboo state whose confession seems destined to cause others to turn and flee. … [L]oneliness inhibits empathy because it induces in its wake a kind of self-protective amnesia, so that when a person is no longer lonely they struggle to remember what the condition is like.

Several of the artists shared underlying reasons for loneliness: an abusive childhood, mental illness and/or sexuality perceived as aberrant. Edward Hopper might seem the most ‘normal’ of the artists profiled, but even he was bullied when he shot up to 6 feet at age 12; his wife Jo, doing some amateur psychoanalyzing, named it the root of his notorious taciturnity. His Nighthawks, with its “noxious pallid green” shades, perfectly illustrates the inescapability of “urban alienation,” Laing writes: when she saw it in person at the Whitney, she realized the diner has no door. (It’s a shame the book couldn’t accommodate a centerfold of color plates, but each chapter opens with a black-and-white photograph of its main subject.)

Andy Warhol was born Andrej Warhola to Slovakian immigrants in Pittsburgh in 1928. He was often tongue-tied and anxious, and used fashion and technology as ways of displacing attention. In 1968 he was shot in the torso by Valerie Solanas, the paranoid, sometimes-homeless author of SCUM Manifesto, and ever after had to wear surgical corsets. For Warhol and Wojnarowicz, art and sex were possible routes out of loneliness. As homosexuals, though, they could be restricted to sordid cruising grounds such as cinemas and piers. Like Klaus Nomi, a gay German electro-pop singer whose music Laing listened to obsessively, Wojnarowicz died of AIDS. Nomi was one of the first celebrities to succumb, in 1983. The epidemic only increased the general stigma against gay people. Even Warhol, as a lifelong hypochondriac, was leery about contact with AIDS patients. Through protest marches and artworks, Wojnarowicz exposed the scale of the tragedy and the lack of government concern.

In some ways Henry Darger is the oddest of the outsiders Laing features. He is also the only one not based in New York: he worked as a Chicago hospital janitor for nearly six decades; it was only when he was moved into a nursing home and the landlord cleared out his room that an astonishing cache of art and writing was discovered. Darger’s oeuvre included a 15,000-page work of fiction set in “the Realms of the Unreal” and paintings that veer towards sadism and pedophilia. Laing spent a week reading his unpublished memoir. With his distinctive, not-quite-coherent style and his affection for the asylum where he lived as an orphaned child, he reminded me of Royal Robertson, the schizophrenic artist whose work inspired Sufjan Stevens’s The Age of Adz album, and the artist character in the movie Junebug (2005).

A few of the chapters are less focused because they split the time between several subjects. I also felt that a section on Josh Harris, Internet entrepreneur and early reality show streaming pioneer, pulled the spotlight away from outsider art. Although I can see, in theory, how his work is performance art reflecting on our lack of true connection in an age of social media and voyeurism, I still found this the least relevant part.

The book is best when Laing is able to pull all her threads together: her own seclusion – flitting between housing situations, finding dates through Craigslist and feeling trapped behind her laptop screen; her subjects’ troubled isolation; and the science behind loneliness. Like Korey Floyd does in

The Loneliness Cure, Laing summarizes the physical symptoms and psychological effects associated with solitude. She dips into pediatrician D.W. Winnicott’s work on attachment and separation in children, and mentions Harry Harlow’s abhorrent rhesus monkey experiments in which babies were raised without physical contact.

The tone throughout is academic but not inaccessible. Ultimately I didn’t like this quite as much as The Trip to Echo Spring, but it’s still a remarkable piece of work, fusing social history, commentary on modern art, biographical observation and self-knowledge. The first chapter and the last five paragraphs, especially, are simply excellent. Your interest may wax and wane through the rest of the book, but I expect that, like me, you’ll willingly follow Laing as a tour guide into the peculiar, lonely crowdedness you find in a world city.

(See also Laing’s list of

10 Books about Loneliness, chosen for Publishers Weekly.)

With thanks to Canongate for sending a free copy.

(A version of this review was originally published with images at my blog,

Bookish Beck.) -

"La solitudine è collettiva; è una città. E non ci sono regole su come abitarci, e non bisogna provare vergogna, basta ricordarsi che la ricerca della felicità individuale non travalica e non ci esime dai nostri obblighi reciproci. Siamo tutti sulla stessa barca, e accumuliamo cicatrici in questo mondo di oggetti, questo paradiso materiale e temporaneo che troppo spesso assume il volto dell’inferno".

-

3.5 stars

I would give the last three pages of this book 20 stars if I could, for exploring the under-discussed topic of loneliness with such wisdom and compassion. In The Lonely City, Olivia Laing writes about her experience with loneliness after moving to New York City. She blends her time in New York with analyses and biographies of various artists, including Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, David Wojnarowicz, and more. I loved portions of this book because Laing opens herself up to such a probing, poignant examination of being lonely. After graduating from undergrad last May, I get the sense that we all try to act as happy as we can, such as by portraying images of perfection and satisfaction on social media even when we feel sad or distraught. I know I have felt and still feel isolated and lonely at times. Through her smart thinking and honest self-disclosure in The Lonely City, Laing shows that it is okay not to be okay, to feel lonely or lacking. In fact, we can learn a lot from not being okay. This brilliant quote exemplifies this message:

"There is a gentrification that is happening to cities, and there is a gentrification that is happening to the emotions too, with a similarly homogenising, whitening, deadening effect. Amidst the glossiness, of late capitalism, we are fed the notion that all difficult feeling - depression, anxiety, loneliness, rage - are simply a consequence of unsettled chemistry, a problem to be fixed, rather than a response to structural injustice or, on the other hand, to the native texture of embodiment, of doing time, as David Wojnarowicz memorably put it, in a rented body, with all the attendant grief and frustration that entails."

I only give this book 3.5 stars instead of 5 stars because Laing's sections about artists felt like tangents at times. I understand that she drew inspiration and meaning from these artists' work, and I love the idea of using art to cope with and honor loneliness. But I wish these sections had been more integrated with her own story, instead of separate chunks pulling us away from the narrative. I wanted to know more about her recent breakup after moving to NYC, her past experiences with loneliness, or her relationship with writing and loneliness. I appreciated the chapters that dealt with the AIDS crisis and social media, as Laing connected these parts with the overarching themes of the book well. Specifically, I appreciated how Laing writes that instead of rushing into romantic relationships to escape loneliness (an unfortunate pattern I have seen way too many people enact), we can befriend ourselves instead and focus on fighting for social justice:

"I don't believe the cure for loneliness is meeting someone, not necessarily. I think it's about two things: learning how to befriend yourself and understanding that many of the things that seem to afflict us as individuals are in fact a result of larger forces of stigma and exclusion, which can and should be resisted."

Overall, recommended to anyone who has ever felt lonely - so all of us, I suppose - and wants to explore that feeling. Artists and art lovers would get an additional kick out of this book. I am grateful to Laing for this kind, intelligent discourse on loneliness, a topic I hope we can all engage with with more compassion to ourselves and others. People partake in such maladaptive actions to hide away from or deal with loneliness (e.g., abusing substances, staying in abusive or dissatisfying relationships, etc.) and Laing offers great alternatives in The Lonely City, with a focus on befriending yourself, creating and appreciating art, and advocating for social justice. I will end this review with one more brilliant quote:

"Loneliness is personal, and it is also political. Loneliness is collective; it is a city. As to how to inhabit it, there are no rules and nor is there any need to feel shame, only to remember that the pursuit of individual happiness does not trump or excuse our obligations to each another. We are in this together, this accumulation of scars, this world of objects, this physical and temporary heaven that so often takes on the countenance of hell. What matters is kindness; what matters is solidarity. What matters is staying alert, staying open, because if we know anything from what has gone before us, it is that the time for feeling will not last." -

تبدو الوحدة وكأنها جزيرة آمنة وسط عالم من الضجيج والصخب

احساس قد يكون مريح ومطلوب أحيانا, ومُوحش وبائس أحيانا أخرى

كتابة تنتقل بين الذات والآخر, وتكشف تفاصيل الوجوه المختلفة للوحدة -

Ali Smith pointed me to Olivia Laing—I think she was planning to introduce her at a conference in Edinburgh. I knew nothing about Laing when I opened this book to the essay about Henry Darger, “the Chicago janitor who posthumously achieved fame as one of the world’s most celebrated outsider artists, a term coined to describe people on the margins of society, who make work without the benefit of an education in art or art history.”

It is very creepy and disturbing, the whole story of the three hundred paintings and thousands of pages of writing Darger left behind at his death, about sex and children and abuse and neglect. Laing’s description of it, and her close research into his life, reminded me of the work of New Yorker writer

Ariel Levy: one doesn’t really want to read it, but once begun, it is hard to tear oneself away.

This book itself is about lonely people, lonely artists, herself as a lonely person. Such a repellant topic; Laing notes the psychoanalyst Fromm-Reichmann, a contemporary of Freud, writes“Loneliness seems to be such a painful, frightening experience that people do practically everything to avoid it….Loneliness, in its quintessential form, is of a nature that is incommunicable by the one who suffers it.”

Exactly, exactly, exactly, I want to say as I turn my attention away. It makes me uncomfortable, suffering from it or not. So why, then, does Laing want to write a book about loneliness?

The truth is, if one can suffer through the sensation of skin-being-sanded while Laing chooses Edward Hopper to discuss during her own period of estrangement, alone in New York City, irreparably separated from her fiancé, her discussion of Hopper’s paintings and his life leave an indelible impression. Hopper met his wife in art school, and they each were forty-one-year-old virgins when they married one another. The chapter becomes a queerly voyeuristic biography of Hopper, his art, and his journal-writing wife whose painting was so derided by Hopper that she stopped painting and became his model.

When Laing moved from Brooklyn to the Village—she can’t have been so lonely, by the way, that she didn’t just return to England unless she likes a little bit that sensation of sandpaper-on-skin—she turned her gaze on Andy Warhol. At first Laing detested his work but after seeing him struggling to speak in a biopic once, she realized his Pop Art, the repeating images in different colors, was the attempt of a lonely boy to fit in."Sameness, especially for the immigrant, the shy boy agonisingly aware of his failures to fit in, is a profoundly desirable state; an antidote against the pain of being singular, alone, all one, the medieval root from which the work lonely emerges. Difference opens the possibility of wounding; alikeness protects against the smarts and slights of rejection and dismissal."

Laing does not neglect Valerie Solanas, the shooter who nearly ended Warhol’s life, who was also “drawn to the excessive and neglected.” Solanas’s work on the SCUM Manifesto puts her smack dab in the middle of a resurgent feminist movement, and yet decidedly outside the mainstream headed by Betty Friedan.

Laing provides context to and critiques of the work of Warhol contemporaries, photographer/artists Nan Goldin, David Wojnarowicz, Peter Hujar, and demonstrates how their work fits in with the alienation developed through loneliness. Laing’s searing chapter on the AIDS epidemic reminds us how the scourge played out in New York, and how it enveloped Warhol and his milieu.

The discussion of “Strange Fruit (for David)”, an art installation created by Zoe Leonard for Wojnarowicz in 1998, is somehow eye-opening, and mind-changing. The creepiness of that avant garde art scene melts to reveal the humanity and real pain in the expression of this art.

So Laing’s own journey through loneliness becomes a meditation on loneliness expressed through the art of others."It was the rawness and vulnerability of [Wojnarowicz’s] expression that proved so healing to my own feelings of isolation: the willingness to admit to failure or grief, to let himself be touched, to acknowledge desire, anger, pain, to be emotionally alive. His self-exposure was in itself a cure for loneliness, dissolving the sense of difference that comes when one believes one’s feelings or desires to be uniquely shameful."

Laing’s skill on this difficult subject of outsider art keeps us curious and bearing our discomfort as she leads us to a deeper understanding of our human condition."Loneliness is personal, and it is also political. Loneliness is collective; it is a city…the pursuit of individual happiness does not trump or excuse our obligations to each other. We are in this together…What matters is kindness; what matters is solidarity. What matters is staying alert, staying open…"

-

Purcell's aria The Cold Song

from his 17th century opera King Arthur:

What Power art thou,

Who from below,

Hast made me rise,

Unwillingly and slow,

From beds of everlasting snow!

See'st thou not how stiff,

And wondrous old,

Far unfit to bear the bitter cold.

I can scarcely move,

Or draw my breath,

I can scarcely move,

Or draw my breath.

Let me, let me,

Let me, let me,

Freeze again...

Let me, let me,

Freeze again to death!

Germany, 1983: final performance by Klaus Nomi

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TnkVg...

Klaus Nomi, countertenor, beautiful soul, born in Germany in 1944

died not long after that performance

on August 6, 1983, at a hospital in New York City, of AIDS

alone

shunned by his friends

no hugs, no nurses would touch him with their bare hands

came to New York and found love and acceptance, fame and a bit of glory

died a a lonely death

his last performance, he sang the last line three times:

Let me, let me, freeze again to death!

he came from Germany to New York City and in lower Manhattan found a community of people, gays, gay artists, made friends, had lovers and boyfriends and sex at the old Chelsea Piers

see how frail he was, how ill

such determination

see the faces of the people in the orchestra

it's said the audience didn't know he was sick

but I think at least some of the orchestra knew

watch him walk down from the stage for the last time

in death he would become an icon, beloved all over the world, inspiring Lady Gaga

the subject of a documentary.

in this book he is one of many lonely, disaffected artists who left home because gay was not okay, found what they wanted or needed in New York, or didn't; for many, death was waiting

they came from all over the country, all over the the world, to be themselves!

to express themselves

to disappear in the shadows of the abandoned Chelsea Piers and have sex with abandon

no idea they were being stalked, many would be picked off, by an invisible transmissible virus

when Gay Related Infectious Disease, or GRID, was killing small then larger numbers of gay men and junkies in NYC

I who was born and raised there, lived there, had not heard of it, but I have vivid memories of being in a small club on Long Island dancing to Klaus Nomi's cover of You Don't Own Me. I loved that song. Until I read The Lonely City I had no idea of the man behind it or his story.

I had no idea who he was. what gay was. really! I did not yet know what gay was. some people I'd gone to school with were dying, died, were sick, and I did not know what gay was. vaguely. school friends, hairdressers (two of whom would die of AIDS), artists, actors, but

I.did.not.know.what.it.meant.to.be.gay.

This book. Wow. The title is ironic: this is about the Intersection of art and loneliness in New York, which would be an inspired name for an intersection in Manhattan, corner of Art & Loneliness, if there were suitable streets available.

Olivia Laing came to New York from London decades later.

I was in the city because I’d fallen in love, headlong and too precipitously, and had tumbled and found myself unexpectedly unhinged. During the false spring of desire, the man and I had cooked up a hare-brained plan in which I would leave England and join him permanently in New York. When he changed his mind, very suddenly, expressing increasingly grave reservations into a series of hotel phones, I found myself adrift...

She chose to stay, with her broken heart and admirable determination, which she partly channeled by researching and writing this book.

I knew what I looked like. I looked like a woman in a Hopper painting.

That first chapter on Edward Hopper gives no clue where the book will lead. It unfolds, and I will not spoil much; Laing has done a lovely job layering people and places. Also not native to New York City, he captured the essence of the loneliness he saw everywhere. He rode the elevated subways and sketched, thus the voyeuristic views of some of his best paintings. He and his wife, also a painter, lived in a small apartment in Washington Square.

Even after he was exhibited at the Met, he wouldn't get a larger apartment. He was a mean man, emotionally abusive, their marriage dance was an ugly one. She stayed. She modeled: that's him in Nighthawks with his back to the viewer, that's her at the counter in that diner with no door, where the kid behind the counter has no way to get out from behind the counter.

This is great writing. Little by little Laing unfurls her story, which dovetails with many of those she relates. Her mother is gay, she's come to be with this man but has realized they are gender-fluid.

There's Warhol, the kid with the speech problems and odd accent and pockmarked face who came to New York and became the ultimate cool insider. Interesting ways The Factory intersects with the theme. Jean-Michel Basquiat, at one point his closest friend: a straight junkie, when he got AIDS Warhol cut him out of his life too. Meanwhile back at The Factory he'd hired three women to type the unsuccessful novel he'd written: one was the drummer from Velvet Underground, and she didn't like the swearing.

Valerie Solanas, and I minded her presence at first but Laing has woven her in intelligently. At one point Laing was staying at a hotel Solanas stayed in. The artist David Wojnarowicz, with whom I wasn't familiar and whose bio I now own, who did many things but is mostly known for his photos taken on the streets of NY of a man in a Rimbaud mask -- one happened to be taken on the corner where Solanas was arrested.

New York is layered that way. Every major city is but this is my hometown. I miss that New York in many ways, before it was cleaned up. I had no idea of what went on at the Chelsea Piers but reading about people's experiences there I rooted for them, for the satisfaction of lifelong pent-up desires. And though I ended up volunteering with people with AIDS in Boston, I've always been missing that piece: the early years in NY. San Francisco is so well documented. I reviewed a novel I didn't enjoy and was asked if I knew a better one. No. Now I can recommend this.

There is a side trip to Chicago, where they bring in two outsider artists. I'd rather they'd stayed in New York and I'd rather those two not be in the book, as interesting as they are, and problematic: Henry Darger, who is covered in depth, and Vivian Maier. No more about them; if like me you're not familiar let Laing tell you or Google them. I didn't want to leave New York and my response to Darger's work was not consistent with the rest.

This is not a long book, seems longer than it is which I mean in a good way, is full of sketches and many details. Even the ones I knew I saw in a new light presented together in the way Laing presents it.

I cried many times. It's not because they were trying to elicit that. Nor sympathy for the abused ones, who don't want sympathy for themselves. I have a list of documentaries to watch now, at least one more book to read -- and an unprecedented number of highlights.

I wanted Nomi to be the entire review, but feared it might seem melancholy or worse, melodramatic. This book is intelligent. There's no pity asked for and none given. Not even for Hopper's wife Jo, who after his death donated her own work, which he didn't support, to the Whitney. They destroyed it.

All the art created. So much went on in those days in lower Manhattan. The lives lived freely, the childhoods gotten over or not, the human materials and the physical ones that are alchemized by people, many of them damaged, some not, into art.

I don't believe the cure for loneliness is meeting someone.

I think sometimes it is and often it's not. The many people in this book, the different stories, the depths, the shallows, the Intersection and intersectionality --

It's subjective. It's complicated. It's sad it's happy it's dirty it's starting downtown moving uptown staying down overcoming addiction love gossip paintings collages shooting shooting up Chelsea Piers accents feeling like a misfit finding freedom chronic isolation The Shunning ACT UP FIGHT BACK, let me freeze to death, it's Jo Hopper posing for Girlie Show in front of the pathetic stove in the tiny apartment Hopper stayed in, in Washington Square. She loved him. So many ways to love. Love can set you free, love can make you tie yourself to loneliness: everything in flux, New York City is The Place Where --

Olivia Laing captured something worth holding tight. -

خالد صدقة بيقول: الوحدة مرعبة

ومع هذا

لا تأتوا

مجيئكم يخيفني

..أكثر من وحدتي.

وأوليفيا لانغ بتقول في كتابها دا: كيف بإمكانك وصف الشعور بالوحدة؟ إنه أشبه بكونك جائعا: إنه أشبه بكونك جائعًا بينما كل من حولك يستعد لتناول وليمة. إنه شعور مخجل ومخيف، ومع الوقت يبدأ هذا الشعور بالإشعاع خارجًا، ليجعل صاحبه أكثر عزلة، وأكثر غربة. إنه شعور مؤلم، بالطريقة التي تؤلمنا بها المشاعر، وله أيضًا عواقب جسدية لا يمكننا رؤيتها، داخل الجسد المغلق. ��يتطور هذا الشعور، ليصبح باردًا كالثلج وصافيًا كالزجاج، ليتضمنك ويجتاحك.

ويمكن دا لُب الموضوع، أن الوحدة لا تُشرح ولا تُشرّح، لأنها غير مفهومة غير للي بيعاني منها.

ولأن الوحيد متهم وبيتم توجيه اللوم على من يشعرون بالوحدة: وهناك ميل تلقائي لرفضهم، أو لافتراض أنهم من جلبوا هذه الوحدة على أنفسهم لأنهم كانوا خجولين أكثر من اللازم، أو لأنهم غير جذابين، أو لأنهم يشعرون بالأسى على أنفسهم. -

In her mid-30s, Olivia Laing moved from England to New York to live with a new boyfriend. The relationship didn't work out, and she found herself stranded on her own in an unfamiliar city, dealing with an almost crippling lack of daily human interaction.

Having spent sizeable chunks of my own life being lonely in unfamiliar cities, I immediately liked the idea as well as the melancholy tone of this book. Laing has all kinds of interesting insights to offer on how loneliness manifests itself – but it should be noted that while The Lonely City presents itself as a memoir of this time in her life, under the hood it's really a book of art criticism, examining the life and work of visual artists (mostly) who addressed loneliness as a subject.

Her main case studies are Hopper, Warhol, David Wojnarowicz, Henry Darger and Klaus Nomi, some of whom I had never heard of, but all of whose work emerges in this study as full of the pain and the hypersensitivity of loneliness – infused with (in a phrase she uses about Hopper) ‘an erotics of insufficient intimacy’. You can look at my updates for some visuals on their stuff – unfortunately it is necessary for the reader to put these references together for themselves, as the book itself is critically short of illustrations.

I loved the memoir bits and thought the criticism bits were only OK, which meant I found the book as a whole a little uneven, though often fascinating. Although Laing has a load of interesting things to say about the artists she discusses, I couldn't shake off the feeling that they sometimes appeared to act as a cover, or safety net, for when talking about herself became too difficult. Tracing Wojnarowicz's nocturnal excursions into the New York gay scene of the 1980s, for instance, leads Laing to a moody consideration of her own sexuality – her sense that she is ‘in the wrong place, in the wrong body, in the wrong life’ – in terms that are first allusive, and finally more direct:I'd never been comfortable with the demands of femininity, had always felt more like a boy, a gay boy, that I inhabited a gender position somewhere between the binaries of male and female, some impossible other, some impossible both. Trans, I was starting to realise, which isn't to say I was transitioning from one thing to another, but rather that I inhabited a space in the centre, which didn't exist, except there I was.

The narrative really comes alive at these points; but it isn't long before Laing ducks back behind another artist again and retreats, if that's not an unfair word, into more analytic criticism. And again – the criticism was interesting! – I just felt that the art and the memoir got in each other's way as often as they reinforced each other. Which was a shame, because I found her really excellent when concentrating on the life writing – on, for instance, the way loneliness has been mediated, yet in some ways worsened, by the modern online world – especially when it comes to the contradictory impulses that drove her on social media:I wanted to be in contact and I wanted to retain my anonymity, my private space. I wanted to click and click and click until my synapses exploded, until I was flooded by superfluity. I wanted to hypnotise myself with data, with coloured pixels, to become vacant, to overwhelm any creeping anxious sense of who I actually was, to annihilate my feelings. At the same time I wanted to wake up, to be politically and socially engaged. And then again I wanted to declare my presence, to list my interests and objections, to notify the world that I was still there, thinking with my fingers, even if I'd almost lost the art of speech. I wanted to look and I wanted to be seen, and somehow it was easier to do both via the mediating screen.

Laing's neat summary of the internet – ‘what seemed transient was actually permanent, and what seemed free had already been bought’ – is perhaps a clue to the appeal of the artists she focuses on, who were either far outside any corporate influence or, like Warhol, were making commodification the whole point of their work. Seeing these lonely artists through Laing's gaze is enlightening – but the links and segues are so good that I spent much of the book pining for a straight-up memoir. -

I will always be lonely.

And this book just validated that feeling some us have had and still having and will continue to have, for the rest of our lives.

While some may think that it is a weakness, artists mentioned in this book (which I never knew existed, thanks Olivia) used loneliness as their means of doing their artworks to its best. At the time that technology hasn't reached its peak yet, these people turned their pain into something beautiful—art. Instead of looking for a way to dismiss that particular feeling, they've come to terms with what the society thought was an illness. Add to it the pressure of the society that happiness is all there is and that people who experience loneliness on a deeper level has no place to be in.

In a city full of people, it can also be isolating. It has always been a belief that living in a city means having everything; which is not always the case.

Olivia Laing points out how living in big city could just as much make you feel (more) alone despite surrounding with so many people.

"You can be lonely anywhere, but there is a particular flavour to the loneliness that comes from living in a city, surrounded by millions of people. One might think this state was antithetical to urban living, to the massed presence of other human beings, and yet mere physical proximity is not enough to dispel a sense of internal isolation."

This book will not tell you how not to be lonely. This book will not tell you how to feel less alone. And neither this book will tell you how to get rid of that feeling but this book will tell you, that loneliness is not a bad thing after all. -

حزينة ، محبطة ، غاضبة

هذا هو رد فعلى على هذا الكتاب

المدينة الوحيدة ، مغامرات فى فن البقاء وحيدا

الكتاب اشبه بسيرة مختصرة لعدد من الشخصيات التى عانت من الوحدة والانعزال الاجبارى من قبل المجتمع لاسباب مختلفة ، يتحدث عن اعمالهم ، وتحليل اعمالهم وربطها بالوحدة والعزلة التى عايشوها ف حياتهم

لكن اين مشاعرهم؟ أفكارهم الداخلية اجزاء نادرة جدا لبعضهم

افكار ومشاعر الكاتبة نفسها التى عاشت هذا الشعور ؟ نادرة جدا

شعرت بالملل الشدييييد فى غالبية اجزاء الكتاب ، تفاصيل لم اهتم بمعرفتها ولم تفيدنى ولم اشعر معها بأى شئ

ربما اكون ظلمت الكتاب لكنى محبطة منه بشده

ليس هذا ماكنت اتحمس لقراءته

ليس هذا ما كنت انتظره

١٩ / ١ / ٢٠٢٠ -

Music: House Of Love - "Loneliness Is A Gun"

At first, you might think this is just the author talking about her loneliness when she spent some time in New York City somewhere around 2000s. Then you realise that it's not only about that, but how artists dealt with their loneliness through art and different gadgets, from Edward Hopper to Josh Harris. It's true that Laing chooses mostly white, mostly male, examples of them, but I somehow feel it doesn't matter too much, since the books variety of material is still quite good in other ways. I seem to have chosen another book based in New York since my book before this was also there most of the time (Ling Ma's "Severance"). For the author, investigating on the artist gave her comfort in her loneliness; for the artists, art gave them relief and a way to express this, express themselves, to make a mark, to be a way to change society. Some were more approved than others, some were only known after their death (being outside artists).

The loneliness here is big city loneliness. Some of the artists here area listed early, some come along as you read. Some appear briefly, some stay on, especially Andy Warhol. All sorts of angles about loneliness are talked about: loneliness as a hunger, loneliness because you are different, loneliness because you are ill (mentally, having HIV etc.), loneliness because you are difficult or hard to figure out or just reclusive. The psychology of it is mentioned, it's ways of damage are mentioned. Loneliness because you are an immigrant, you don't talk quite good English, you don't want to be forced into a gender (here some comment on the film "Vertigo" and the forcing within it).

You do sometimes feel the need for sameness. To be liked. To get likes, comments. To be watched on film, Youtube, on stage. You use machines to protect you, to get you through people, to make people be with you talking, performing. Different subjects flow in and out: Rimbaud masks, the experience of visiting the sex scene at Chelsea pier (and the consequences in first waves of HIV), the marks of childhood causing further loneliness ways in adulthood. Online 'company, online loneliness, online as control, online being watched and a watcher. The film "Her".

- this, the last two sentences above, the point in the book brought reality of mine firmly in front of me... and like many, I've had: loneliness in school, lack of friends, lack of understanding social rules, lack of current friends etc. etc. etc.

"Loss in the cousin of loneliness", and we lose some of the people as the book comes towards the end, but we realise what art brings to lonely people, to the artists. To inform, to be remembered. To move us to certain emotions, like that piece of fruits stitched back together, like those Warhol boxes of hoarded stuff. There's the memory. There's the art that makes us less alone, both the watcher and the maker of them. Art is useful - we are useful. Some way, some day(s). -

I really enjoyed this book. It's about loneliness, and through lives of different artists, most of who I knew very little about, she speaks of the need in all people in general, to feel a part of something. Wonderful read.

-

I first read this book some time after moving to a new, 'flashy' city, one that made me feel isolated and lonesome despite being surrounded by some part of its 12-million-strong population at all times. Olivia Laing wrote The Lonely City after a similar move to the city of New York, except she moved towards a love that didn't work out, while I had to move away from one that can't help but.

Now, a few months later, the island of isolation calcifying around this global pandemic and a crisis of intimacy looming right before my 22nd birthday has driven me to this book again. Just as the first time, it moved me — often to tears and always to a sense of calming reflection.

A unique and riveting piece that offers solidarity for solitude, The Lonely City: Adventures In The Art Of Being Alone is part memoir and part meditation on a pervasive sense of loneliness and what it says about the world we grow to live in each day. Laing explores here different mores of loneliness and seclusion through the lives and art of artists like Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, David Wojnarowicz, Henry Darger and Klaus Nomi; alongside many others weaving in and out; highlighting gentrification as the fountainhead of loneliness as we experience it today. From Hopper's Nighthawks to Darger's Realms, from Valerie Solanas' self-published manifesto, Josh Harris' experiments with the blurring lines of the real and the social and Greta Garbo's solitary walks through the streets of NYC, to AIDS and Billie Holiday's "Strange Fruit" (as well as Zoe Leonard's eponymous artistic tribute to Wojnarowicz); Laing walks through and appreciates the experience of loneliness and the human need for intimacy, understanding, and contact comfort without voiding it of its pathos, its raw edges, or its sense of hope.

This book takes one on a journey from the loneliness as a private hell behind glass walls and devices to inhabiting the trauma and communal sense of alienation that accompanied the experience and injustice of AIDS, while at the same time making space for the misunderstood and the disregarded — such as Jo Hopper, whose own career ended in submission to that of her husband; or Valerie Solanas and Henry Darger, whose unceasing creativity was a refuge from the mistreatment and harassment of the outside world — as well as infamously contradictory people like Andy Warhol. Laing looks at loneliness as something that is both a curse and a mark of defiance. The Lonely City is also a map, in both space and time, of New York; a portrait of the city through its loners, whose lives filled with its exhilarating charm and distance in equal measures. In including here her own experience of getting lost and lonely, Laing's nuanced mapping of the pains of solitude and loss through music, art and biography in this book lends to it a sense of catharsis.

What touched and resonated with me the most, however, was the sheer brilliance of the chapters in the latter half of this book which talk about the growing loneliness in a world of instant messaging, screens and fragmented personalities. These open an empathetic discussion on the sensitivity and shame that make the lonely unreachable and even repulsive, and exploring the personal, political and collective aspects of this feeling. In one particularly insightful passage, she writes:"Amidst the glossiness of late capitalism, we are fed the notion that all difficult feelings — depression, anxiety, loneliness, rage — are simply a consequence of unsettled chemistry, a problem to be fixed rather than a response to structural injustice or, on the other hand, to the naive texture of embodiment, of doing time, as David Wojnarowicz put it, in a rented body, with all the attendant grief and frustration that entails."

Beautiful, lucid and deeply poignant, the emotions and insight that flare throughout every reading of The Lonely City remind me of Fernando Pessoa, my favourite literary 'outsider', and the only one whose sense of abandonment and disquiet could touch and resonate with my own — until now, that is.

This book makes me feel a little less lost — I hold this book and it feels like being held. When the feeling of being alone in a crowd beckons once more; as it soon will; I will pick it up again. -

This was my first non-fiction book for a long time, and I was very curious both about the subject of loneliness, but also to see what was hidden behind the beautiful cover.

Basically, Olivia Laing explores how it is to be lonely in a city surrounded by people. She has lived in New York City for a certain period of time herself, and during that time she felt extremely lonely.

This non-fiction book isn't just about her personal experiences, though, because it also dives into other artists' experiences with loneliness, artists such as Andy Warhol as well as some people whose work I didn't already know of - and this is when things got interesting. I loved how this exploration educated me and made me aware of dark places and diverse art and people that I never even knew of.

While you might think that the exploration of loneliness must be a dark one, I was happy to find out that Olivia Laing actually finds positives to this phenomenon that a lot of us fear. It was truly a remarkable piece of literature that made me think a lot, and I am intrigued to read more from Olivia Laing just to learn more of her interesting thoughts and view on life. -

While Liang's writing and research are impressive, this didn't come across as a cohesive work for me. The loneliness theme felt forced, and every time it was introduced I often felt that the artists discussed weren't in fact lonely but simply dedicated to their craft. In addition, I was put off by the amount of content that seemed to be directly pulled from Wojnarowicz's " Close to the Knives". I'd like to read this book in the future, and Liang seems to have simply summarized the plot points and turned that into a chapter. I'm not sure what her analysis (or lack there of) added to Wojnarowicz's story, or why she felt the need to re-tell his book and strip others of the opportunity to hear the story in his words. Overall an annoying read.

-

كتاب جميل جداً جداً جداً انصح الجميع بقرائته حاولت اقرأ هالكتاب بمهل شديد جداً لانه كتاب ثقيل بالمعلومات الجميلة الاكيد انا راح اعيد قراءة هالكتاب يوماً ما 💜💜

-

I'd been saving this book for the perfect moment, and I picked it up now after realising that this moment had descended on me months ago. I've been trying to map my own loneliness in a new city, I've been trying to accept it, to not be ashamed by it. I've been working from my room, and have stopped going to the office. My loneliness is ironic, it wants to fester and grow. It has made me turn my room into precipice, I look at myself sitting at the desk, staring at the laptop while my fingers punch the keys. I look so solitary, so lonely in the dimmed down lights. I needed someone to guide me through this, and Laing couldn't have done a better job.

In tracing out solitude, confinement, loneliness and the intersections between them through art, Laing has created a shrine of the lonely. So I read this book, considered it sacred, offered prayers, asked for relief (from loneliness of course) and left silently. I sought refugee from myself at this shrine. This book answered my prayers, sometimes hissing, sometimes soothing. Because that's the thing about loneliness, it isn't elegant at all. You can't be graceful about it. But you can face it with dignity, as Laing did, though she was naturally afraid of failing all along.

I should have eaten this book more delicately, instead I devoured it in a hungry gorge. So my loneliness not only resonated with it, but responded too. Reading this book is like running in a stranger's garden after not having seen a single flower for years. It's a very beautiful and overwhelming garden. -

101st book of 2020.

This book begins with the dedication: 'If you're lonely, this one's for you.' It is rather apt for the current situation, which we are, hopefully, emerging from.

Laing surprised me. I'm a huge art fan, and have been since I was a child. For many years I have admired Edward Hopper, who is the focus of the first chapter. Recently, I have been reading countless things about Andy Warhol for a University essay, so, albeit too late to include in my assignment, I was interested in reading about Warhol again in the second chapter. From there, I was in more uncharted territory. Laing then writes, notably, about Henry Darger and David Wojnarowicz. And all the while, she manages, in just shy of three-hundred pages, to draw on loneliness, AIDS, social media, and our generation as a whole, and of course, art itself. The most notable quote from the book, which I can't find exactly, is the recurring image of loneliness as a block of ice in which the lonely is trapped in. Laing herself was lonely in New York City, and art was her way out. She surprised me with how little she was involved in the book too. The first few chapters, she is almost non-existent in the narrative, other than her voice. Later, she seeps in a little more, walking the city, the snow, the light on the walls, and her laptop, the seductive, but dangerous, companion.

Above all, Laing ties all that is said to things she has said previously and things she goes on to say. In the end we are trapped in the epicentre of her web—around us, thousands of thoughts, linked, and illuminating. -

"لا أؤمن أن علاج الوحدة يتمثل في العثور على حبيب، ليس بالضرورة. أعتقد أنه يتعلق بأمرين: تعلم الطريقة التي يمكنك فيها أن تكون صديقاً لنفسك وفهمك أن العديد من الأشياء التي تبدو وكأنها ابتلاءات تعرضنا نحن لها كأفراد هي في الحقيقة نتيجة لقوى اجتماعية وسياسية أكبر منّا تتعمد فرض الشعور بالعار والإقصاء، والتي يمكن ويجب مقاومتها."

-

(1) Premessa: la solitudine è un concetto/stato che mi interessa molto. C’è chi la cerca, chi non ne vuol sapere. Dire di sentirsi soli sembra un fallimento, tanto più oggi, dove sembra che tutti abbiano vite più fighe della tua. È per forza qualcosa che ci/mi riguarda.

(2) Di cosa si parla? Più o meno di arte, società, relazioni, omosessualità, sesso, aids, New York, internet, isolamento urbano. Solitudine.

(3) È interessante? Sì, lo è, anche se a tratti. Potenzialmente è un saggio valido, ben raccontato e di ampio respiro. Nella mia lettura, però, manca di un centro focale, un obiettivo chiaro. Si parte con l’autrice che ci racconta il suo arrivo a New York, una città dove non conosce nessuno e in una situazione mentale in cui fa fatica anche solo a parlare o a mischiarsi alle altre persone. E mi dico “bello, continua così, sono qui vicino a te e ti ascolto”. Solo che poi prende la tangente e si inizia a parlare di Hopper, Warhol, Basquiat e altri artisti americani meno noti, ognuno circondato da una sua idea di solitudine.

(4) Su tutto, troppo Warhol. Voglio dire, la mia idea di isolamento urbano contemporaneo non è Warhol, e 1/4 del libro gira lì intorno.

(5) Davvero migliori, per me, sono le pagine in cui il memoir si incastra col cambiamento della società che conduce a forme estreme di isolamento. Peccato non siano molte, ma alcune sono calibratissime. Tipo questa:

Ogni giorno, al risveglio, prima ancora che i miei occhi fossero davvero aperti, trascinavo il portatile a letto e vagavo come un’ubriaca su Twitter. Era la prima e l’ultima cosa che guardavo, una discesa infinita tra i tweet di estranei, istituzioni, amici, questa comunità effimera in cui io ero una presenza senza corpo e incostante. Rovistavo in quella litania domestica e urbana: soluzioni per lenti a contatto, copertine di libri, il morto del giorno, foto di proteste, vernissage, battute su Derrida, i rifugiati nei boschi della Macedonia, hashtag vergogna, hashtag pigrizia, il cambiamento climatico, una sciarpa persa, battute sui Dalek: un flusso di informazioni, sentimenti e opinioni a cui certi giorni, forse quasi tutti i giorni, dedicavo più attenzione di qualsiasi altra cosa nella mia vita.

(6) Considerazione per invasati: nella mia biblioteca Città sola non è ancora arrivato. Allora ho fatto una ricerca nei cataloghi nazionali per capire come veniva catalogata quest’opera abbastanza inclassificabile. A Mantova e Viterbo finisce nella CDD 823, ovvero Narrativa inglese. Mi pare un’ipotesi abbastanza creativa (o malsana), basterebbero l’apparato di note e la bibliografia a far scartare il pensiero che questo possa essere un romanzo. Tutte le altre biblioteche scelgono la CDD 700.19 - Arti - Principi psicologici. Ci può stare anche se lo trovo riduttivo. Per me questo non è un libro di arte, per quanto ne contenga parecchia.

Personalmente la catalogazione che trovo più adatta è la CDD 302.54 - Individualismo sociale. Studi sociali, modernità, dalle parti di Bauman ma meno accademico.

(7) Citazioni da Il tempo è un bastardo e Her.

(8) È una lettura piacevole, che offre spunti soprattutto se si apprezza l’arte americana del secondo Novecento. Ma non è un saggio che dà un punto di vista esaustivo sull’argomento. Sembra più un punto di partenza, e il finale è piacevole ma non affonda il colpo.

Soprattutto nel dire che ciò che conta, a livello di società per combattere la solitudine, sono gentilezza e solidarietà. Bene, me lo segno.

(9) La sfilza infinita dei ringraziamenti alla fine fa abbastanza effetto, per un libro che parla di solitudine.

(10) Quando sono arrivata a New York ero a pezzi e, per quanto perverso possa sembrare, il mio modo di recuperare una sensazione di interezza non è stato incontrare qualcuno o innamorarmi, ma guardare le cose che gli altri avevano fatto e, grazie a questo contatto, lentamente comprendere che la solitudine e il bisogno non equivalgono al fallimento, ma indicano che siamo vivi. (…) La solitudine è personale, ed è anche politica. La solitudine è collettiva; è una città.

[69/100] -

The subtitle of The Lonely City, 'Adventures in the Art of Being Alone', has a double meaning: as well as being a book about the experience of loneliness itself, this is a book about the role of loneliness in art. The starting point is Olivia Laing's own period of intense loneliness, living in New York after the end of a relationship, bringing to life the so-often-true cliche of being alone in a crowd, isolated and displaced in the centre of one of the world's most populous cities. She makes a study of several artists and photographers, chiefly Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, David Wojnarowicz and Henry Darger, and also talks peripherally about the work of Valerie Solanas, Josh Harris, Zoë Leonard, Peter Hujar and others. The resulting reflections touch on everything from the evolving role of the internet in society to Laing's own gender identity.

I loved The Lonely City, but it's unusually hard to pin down what's so good about it, partly because it's just such a patchwork of genre components - creative non-fiction, memoir, art history, psychology and sociotechnological commentary are all thrown into the mix. Rather than making the book seem like a hodgepodge of nothing much, this makes it stronger, and like the best of this type of writing, it made me keen to find out more about some of the subjects it touches on. The depth of Laing's research is apparent, but it's the personal ruminations that hit home the hardest. There is a clear line drawn - repeatedly - between solitude and loneliness, a distinction that isn't made often enough. Laing also writes incisively about how an online existence can alleviate and/or crystallise individuals' isolation, avoiding the tedious 'the internet is making everyone lonelier' proselytising that typically pervades writing about that particular subject. Along with her openness about her own thoughts and feelings, these points make Laing's observations feel fresh.When I came to New York I was in pieces, and though it sounds perverse, the way I recovered a sense of wholeness was not by meeting someone or falling in love, but rather by handling the things that other people had made, slowly absorbing by way of this contact the fact that loneliness, longing, does not mean one has failed, but simply that one is alive.

Recently, when I (briefly)

reviewed Emma Jane Unsworth's

Animals, I mentioned that I felt so relieved and validated by the ending that I was overwhelmed by a feeling of wanting to actually thank the author for it. I had the same feeling upon finishing The Lonely City. Laing emphasises how much solace she found in the work of her beloved artists, but doesn't suggest this ought to be seen as some sort of cure; there are no solid conclusions about how one 'should' experience, or seek to combat, loneliness. Despite this - actually more likely because of it - The Lonely City is an incredibly reassuring read for anyone who has ever been lonely or struggled with their own experience of solitude.

I received an advance review copy of The Lonely City from the publisher through

NetGalley. -

I live alone, and by alone I discount two barnacle-like cats who obviously think I'm the tops. So I was attracted by Olivia Laing's title, especially the subtitle "Adventures in the Art of Being Alone." I thought, hmm, is there an art to it? Am I missing something that might make me feel less isolated from the teeming world? And at first I believed the book might be headed in the direction I assumed, towards artful solitary living.

Despite the great writing, I was left slightly disappointed. The subtitle is not about the art of being alone, it's about loneliness as depicted in art. Thus, the author moves through an examination of the lives and output of artists like Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, David Wojnarowicz, Zoe Leonard, and Henry Darger, all the while weaving her own experiences of loneliness into the narrative. This is not to say that a reader could not relate to the lonely realities of these artists - it's just that I could not relate. Still, I enjoyed Laing's analysis of some of Hopper's better known paintings and I most definitely learned about artists that had been unknown to me.

Loneliness is a universal condition. You don't have to live alone to feel it. Laing's book has many insightful offerings that could strike a chord in a reader particularly susceptible to isolation. In the final chapter, Laing writes: "I don't believe the cure for loneliness is meeting someone, not necessarily. I think it's about two things: learning how to befriend yourself and understanding that many of the things that seem to afflict us as individuals are in fact a result of larger forces of stigma and exclusion, which can and should be resisted." -

This had an interesting premise and started out promising, with the author reflecting on her own experience lonely in NYC after moving there from overseas. In the first couple chapters, it was somewhat interesting, albeit depressing, to learn more about some well-known artists and how loneliness shaped them and their work.

By the third chapter, however, I gave up. When another artist's biography quickly devolved into a list of the many specific horrible ways he was abused by his parents, I had enough. I quickly glanced at the end to see what the author came to with all this. That was more than enough for me.

I actually wish I'd stopped sooner. I don't know how long it will take for some of those awful images to leave me, and wish I had never let them in. Make sure you're up for some really depressing, awful stuff if you decide to read this book. All the people who loved this must be much hardier than me.